Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski), Mitsou, 1919, black ink on paper, 6 by 4.75 inches (courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Copyright Balthus)

by Tina Engels

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is currently showing works by Balthus in an exhibition entitled Cats and Girls—Paintings and Provocations. Exhibited alongside the 35 early to mid career paintings of portraits, adolescents and companion cats in striking interiors are 40 black and white ink drawings from the book Mitsou. Mitsou was published when Balthus was 11, and includes a preface written by Rainer Marie Rilke, then his mother’s lover. The exhibit begins with paintings dating from 1935 and moves through to works from the 50’s. The show concludes in the final gallery with 40 drawings from Mitsou. The paintings are juxtaposed with early drawings, offering moments of rarity and complexity, as well as a glimpse of a painter sui generis. It is a rare occurrence to see these paintings and drawings shown side by side.

Sabine Rewald curates the current show at the Met, in which the prodigy as precursor to master is revealed. Being born a prodigy does not guarantee prophetic fulfillment of such genius. In the final room of the exhibition, Ms. Rewald reveals youthful drawings from Mitsou, inferring a path to virtuosity. Both Rilke’s preface and recognition of Balthus foreshadow this transition. Witnessed in the drawings is an intensity of emotion that predicts a disposition to later urgent and repeated explorations in painting. This resolute path is maintained throughout his 90 years. How rare to witness so many transitions of exploration and development? Elizabeth Sewell, a philosopher and poet often shared this aphorism with her students, “Genius begins where it intends to continue”. (( Schenck, David. Nonsense, Nothingness, and Remdeption from Lewis Carroll: Voices From France. Elizabeth Sewell. The Lewis Carroll Society of North America, 2008. Print )) These words whispered while images appeared and sustained a growing labyrinth of complexity.

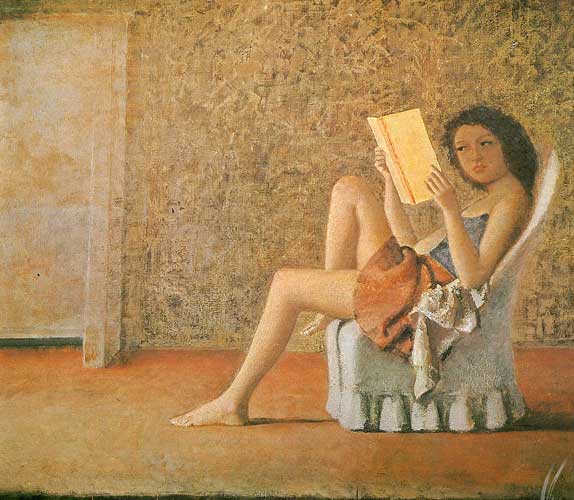

Katia reading 1974 180 X 210 cm

Pictures of adolescents and childhood as artistic preoccupation lined the walls of the galleries at the Met. I approached these images as if it were our first encounter and in this context it was. Accepting “the invitation” from Balthus, I attempted to come to the paintings. An admirer of these works, I avoided feeling any sense of complicity, or exploitation. Any urge toward the voyeuristic fell away before the quality of the paintings. I would caution a viewer that a 21st century American mindset seemed a deterrent to viewing the work. It seemed unfortunate that the Met needed to place a warning that some images may offend the viewer and that they felt it necessary to change the title from Cats and Girls to Cats and Girls–Paintings and Provocations.

India Ink on Paper 30 x 45.1 cm New York, The Museum of Modern Art, gift John S. Newberry

Moving through a painting is a difficult undertaking. Often difficult for the painter, it extends its complications to the viewer. In A Balthus Notebook, Guy Davenport observes, “A work of art, like a foreign language is closed to us until we learn how to read it. Meaning is latent, seemingly hidden. There is also an illusion that the meaning is sealed.” In fact, the illusion or story may lie concealed within the forms. As in a foreign language, meanings are subject to culture, reference and context. Balthus intentionally creates works that defy conclusion and, for lack of a better word, ‘realistic’ interpretation. He willingly embarks on a journey that Rilke might describe as ‘going inside oneself’, allowing for a new fusion of response. These paintings became a prospective model for another kind of thinking – past and present in suspension – the paintings become tableau, a theatre of potential.

Drawing Room, 1942, 114 x 146 cm Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

Balthus employs a mode of thinking that is linked intrinsically, both to the pictorial structure within the works and a visual interior world that holds his motif. Some subjects pose in groupings, yet appear to exchange thoughts or private musings. The pubescent girls and cats radiate calm detachment, unaware of their surroundings. The figures interact in silent worlds, but relate visually as if in a quiet dance. The suggested rhythmic linear movements are choreographed to act in unison with color, form, and subject. We are not invited to join the story, or asked to act as voyeur, but are kept at a protective distance under the watchful eye of the painted or the creator. Balthus asks us to address the paintings as fictions within a tradition, and to do so directly.

Balthus spends much of his life in a seemingly self-imposed solitude, surrounded by a select cultural elite. He devotes himself to creating paintings with ‘lasting quality’. Balthus does not appear to move through his paintings alone. His guides come from both visual and literary worlds. As a young boy, he was mentored and given friendship by Rainer Marie Rilke – their relationship being somewhat akin, one might say, to that of Virgil to Dante. The uniqueness of this relationship continued until Rilke’s death in 1926. In 1921, when Balthus was eleven, Rilke wrote a preface to the publication of Balthus’s book Mitsou. Later Rilke dedicated the poem Narcissus to Balthus. Returning this gesture, Balthus dedicated a painted copy of the Louvre’s Narcissus by Poussin. During and after Rilke’s death Balthus’ intellectual circle widened. It came to include Bonnard, Matisse, Marquet, Derain, Jouve, Artaud, Cocteau, Giacometti, Gide, to name only a few.

Le Rêve (The Dream), 1955, oil on canvas, 130 x 163 cm. Private collection

Not belonging to any particular ‘ism, Balthus is characterized as a painter who references substantive art historical and literary subjects in his paintings. His paintings are void of mere quotation or appropriation. Balthus makes images that become part memory, personal inquiry and include sage voices from antiquity, which impart an artistic sense of déjà vu. His dramas are viewed through a modern eye, fully aware of its 20th century lens. Yet, one senses his passion for ‘the timeless’ in art historical worlds. He recognizes the necessity to embrace these worlds to forge new pathways within his pictorial spaces. This active dialogue with ‘tradition’ acknowledges that work from the early Italians remains fresh and alive, and that they are, more importantly, a part of his artistic past.

Still Life with a Figure 1942 74 X 93 cm oil on wood

Balthus has lived with these works in Italy and includes the substance of his experience within his painted worlds, through visible and intimate conversations with Italian artists of the Quattrocento and the Sienese. Places, archetypes, painters and historical references are seen through a Balthus eye. He is well acquainted with the modernist works of Courbet, Cezanne, Picasso and Derain. He may figuratively wander the “Piero Trail”, encounter Masaccio, the Sienese and Classical French painting, Poussin, de La Tour, but refuses to use these worlds as device, or to borrow style. Perhaps the rarity of his vision has something to do with his ability to converse with past masters, having viewed them himself as a modern.

The first gallery housed portraits, and included the brash, angular self-portrait, where at age 27, Balthus proclaims himself “King of Cats”. The next gallery shared dreamy adolescent depictions, ennui, troubling encounters, and interiors that become characters in the prevailing mood of these dramas. Balthus begins to reveal the intensity of his commitment to color and pictorial structure. It is evident that the parts in a picture maintain a consistent structural relationship to the bigger sense of the whole. An enormous aspect of the conversation within the paintings becomes wedded to the creation of pictorial space and an acute awareness of the “nobility of design” as in desegno, such as in the grand figurative paintings of Poussin and Claude.

Ancient Pompeii Fresco Detail Naples

In the final room of paintings are works from his time in Chassy. These thickly encrusted paintings, reminiscent of Pompeian and Italian frescoes, demonstrate his intent to place his work in the category of the ancients. The densely crackled surfaces illuminate a flattening of form that meanders through space and springs to a flattened surface on command. The rigor of arabesque, its articulation as it is linked to color planes, engages with almost flawless interruption. His color, sometimes patterned or decorative, is at times reminiscent of Persian rugs and textile finery, while other paintings convey a weight tied to spatial intricacies.

Devoid of illustrative narratives, Balthus is an unrelenting master of the enigmatic. Within a painting, whether imagined or believed, logic, geometry, and dreams fuse and intersect. He may inhabit a symbolic element in the painting, such as a cat or mirror, but narratives remain concealed within the forms, in the ambitious complexities of pictorial construction. The relationships within a Balthus space are never predictable. The distance between things is immeasurable. Color linked passages are tied to the planar structure of composition which simultaneously teeters and surprises. Through the hint of a grid, changes, removal, pentimento, subtle clues are left, lending to a sense of the painting’s history.

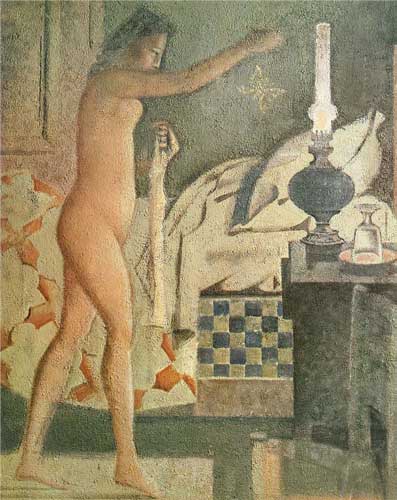

The Moth 1960 162 X 130 cm Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

Balthus uses color as the strongest link to the pictorial structure in his mid career to later paintings. He is a both a brilliant draughtsman and colorist for whom Seurat seems more than just an acquaintance. Where Seurat began with color and pictorial structure, Balthus seems to have moved forward using weighted color planes as a key to configuring his paintings. He finds ways to have these forces act in unison by creating a lyrical merging of color to plane, plane to geometry, and drawing to all elements.

Alluding to the impossibility of painting and the implausibility of the moment constitutes poetic faith. Balthus joins poets and philosophers in acknowledging the prerequisite hazard for those who would make paintings/art. The poetic voice walks jagged terrain on this journey well aware of the risks “in the work”. In Letters to a Young Poet, Rilke calls forth ”images from your dreams, and the objects that you remember.” Rilke once more: “…a work of art is good if it is arisen out of necessity.” We, the viewers, witness this necessity.

The Golden Fruit, 1956 160.5 x 159 cm Private Collection, Paris, France

The best Balthus paintings remain in flux – searching, fresh and ambitious. By retaining an openness in the work and rejecting the static finality of conclusion, he reveals the potential for movement. The works become fictional worlds where all things are possible and provide clues that entice the viewer into the impossible reality of painting. The momentary can cause anything to happen or suggest that something may have happened. The artist wanders through an idea, reasserting its logic or imagined believability. Time and a space exist differently here and propose an alternative metaphor for the impossible, implausible reality of painting.

For the greater part of a century, “genius continued”, in the form of quest and query, clarifying its questions to author, offering passage as its legacy. Andrew Forge wrote on Degas, “artists follow the work as much as lead.” Throughout his life, Balthus may swim against current, or ahead of its force, but is never left behind its energy.

Tina Engels is a Chicago based painter, who also teaches at the American Academy of Art.

Absolutely fantastic review!

This was so interesting Tina! You made wonderful points and really made me study his works with a new point of view. Thank you!

Nicely written and perceived !

Who could still have doubts about l oeuvre de Balthus?

Thanks for this review

I saw this show twice last week. Too bad it doesn’t include any of Balthus’ later work, which for me is his best. Those rich, encrusted surfaces and those solemn,simplified figures all locked in tight, always make me feel like I’m in the heart of painting. That said, its an important and interesting show that anyone interested in painting, let alone cats and girls, should see. Balthus, in his cranky, idiosyncratic, swimming-against-the-modernist-current attitude, is an example to anyone who thinks they’re an independent-minded artist.

Wow!! Who knew that the mild mannered painter in the studio near mine was a fabulous writer as well?? Tina, this is great. Your insights are fresh and original. I’ll be seeing the show in a few weeks and will carry your words with me.

xo,

Kathleen

Great article Tina. I hate to say I was in the Met during the exhibition but went to see Corot and Daubigny instead!

Whenever I read Berenson’s wonderful essays on art I gain immensely, both from an art historical context, as well as an artistic one. This review has engendered a similar experience: In doing excellent justice to Balthus, I feel it has also ennobled me with it’s delight in the psychology, philosophy and love of Balthus’s world. It has also given me much insight into what can be gained, as an artist, when the exploration of the structure of the pictorial space is resolute. Thank you Tina.