A three-person show at Sideshow reminds us that Expressionism, in the right hands, remains as vital as ever.

Review by John Goodrich, guest contributor

Crossroads with Lynette Lombard, David Paulson, and Thaddeus Radell, September 6 – October 8, 2017 at Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

Expressionist painting might seem simply a matter of strong passions and quick reflexes – an instinctive, almost automatic, unburdening of the soul. In reality, in order to persuade, an Expressionist must perform a neat trick. He must give himself over to a state of extremis, of unfiltered perceptions and emotions, while still retaining the wit to communicate them. She needs to employ the language of painting to go beyond the purview of any language. He must, you could say, have the self-possession to articulate a dispossession of the self. Imagine Odysseus, lashed to the mast to withstand the sirens’ singing, all the while minutely directing his crew: “A little starboard, men, a little more – that’s it!”

In clumsy hands, such a performance could seem indulgent. This is not the case, however, with Crossroads, an exhibition of three mid-career painters – Lynette Lombard, David Paulson and Thaddeus Radell – whose work is clearly both compelled and disciplined by a knowledge of painting. (By way of disclosure, I should mention that I was hired to design the catalog accompanying the show.) True to the expressionist aesthetic, the work of all three teems with turgid, built-up colors and gestures. But the urgency expresses itself not just technically, in manipulations of style and craft, but also through the rhythmic relationships of internal forms. The urgency, in other words, is more than a style.

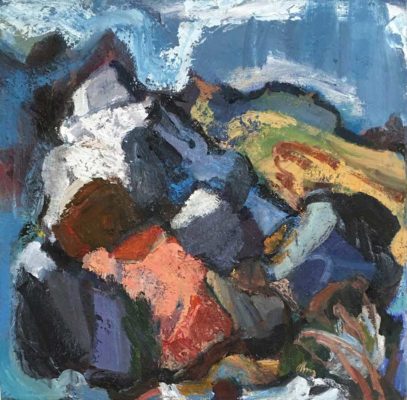

All the paintings in the exhibition are representational, and most rooted in traditions of landscape. Beyond this the artist’s approaches are quite different. Alone of the three, Lombard’s paintings are unpopulated by human figures, and also appear to be anchored in immediate observations – though these are heightened by twisting, vertiginous plunges of space. Despite such distortions, Lombard’s sure sense of form and color convincingly locates every element, whether it’s a road winding across the bottom of the canvas (practically beneath our feet), or mountains rising distantly, or fields spreading in-between. In some of the larger canvases, the urges to represent and to gesture seem to alternate, as if the artist were placing some gestures within post-modernist style quotation marks; in the six foot tall Swell, for instance, a large, unidentifiable orange stroke snakes down the canvas, connecting more recognizable elements. By contrast, the small, incisive Maghery, Ireland simultaneously imparts identity and pictorial energy to each form. Here, sheathes of turquoise, purple and yellow-green become receding planes of earth, palpably carving the space around a single vertical tree.

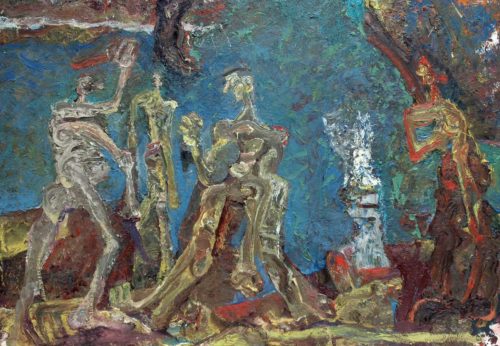

Paulson’s fiercely-hued landscapes, teeming with distended figures, appear at once more personal and more removed. His surfaces – gnarled and knotted, as if stirred from molten pigment – feel intimately tormented, but his scenes read like unearthly dreams. The figures could be caricatures of humans, variously wraith-like, lumbering, stretching and coiling – at once humorous and haunting. Thanks to the resolve of Paulson’s gestures and color, however, these figures embody, rather than simply depict, exotic states of mind and body. For any artist, referencing the great masters can be hazardous – a reminder of their own relative shortcomings – but to Paulson’s great credit, one feels distant psychic echoes, and not just witty recollections, of some powerful precedents. The Pugilist captures the drama of Daumier’s fluid, high-contrast modeling; Scarborough Beach suggests van Gogh’s radiant recession of landscape planes; the march of totem-like figures in Jelly Road recalls Egyptian wall paintings.

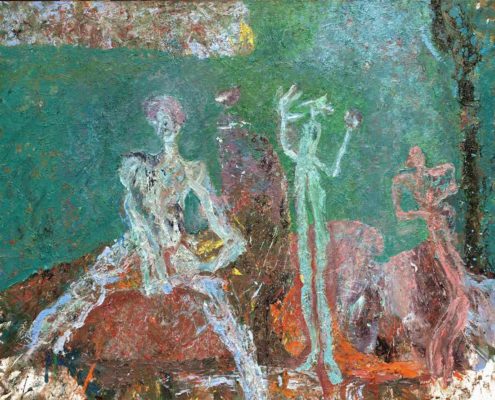

While less specific in the individual gestures of figures, Radell focuses more directly on historical subject matter, as evidenced by such painting titles as Purgatorio and Study for a Portrait of Iago. Such scenes he conjures with heavily reworked surfaces, built up of layers of troweled and scraped paint, sometimes embedded with shreds of burlap. Into this pulsing flux of color – the artist prefers vivid blue-greens and red-inflected earth colors — he incises forms with tenebrous black lines. The quavering, emergent forms effectively recall cycles of decay and rebirth: lives condensing from and into a background current. The inspired installation, one above the other, of two densely articulated eight foot wide paintings, Purgatorio and Acheron, asserts this effect on an epic scale. Other notable paintings include Fallen Man, which, though more lightly rendered, sturdily locates a row of figures above an enigmatically prone one. Some smaller canvases evince a raw but luminous efficiency; the reddish-orange volumes of Study for a Portrait of Edmund cohere, in striking fashion, from a sea of grayish blue and green fragments.

Expressionism is a style that we’ve all seen before, from the landscapes of Turner and Soutine to the portraits of Munch and Beckmann. In the mid-twentieth century, in its abstract incarnation, it changed the course of modern art. But one gets the impression that for all three artists in Crossroads the expressionist style is ultimately a means rather than an end. Raw textures and exotic imagery happen to be the vehicle these artists need to unlock something even more mysterious: the elemental energies of forms on a canvas.

Leave a Reply