This past August I was fortunate to meet with Margaret McCann in her studio in NYC for an interview. My good friend and fellow painter, Matthew Mattingly, joined the conversation with many brilliant observations and comments.

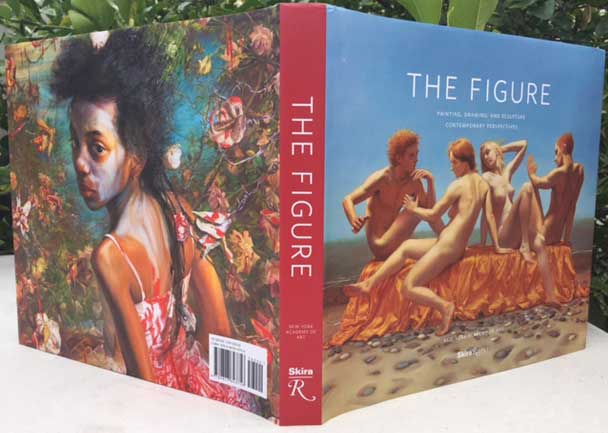

Larry Groff: Thank you, Margaret, for talking with us about your painting, background and the new Skira/Rizzoli book you edited that came out last fall, The Figure What does it entail?

Margaret McCann: The Figure responds to David Hockney’s “Secret Knowledge” to some degree – several artists, among them Judy Fox, F. Scott Hess, Jerry Kerns, Edgar Jerins, Alex Kanevsky, Steve Mumford, Richard Phillips, Rona Pondick, Judith Schaecter and Nicola Verlato openly describe how they use traditional as well as modern techniques like photography, Photoshop, or 3D computer programs. The book focuses on painting and sculpture with some discussion of drawing and printmaking, with amazing artwork by NYAA alumni like Leslie Adams, Ali Banisadr, Amy Bennett, Bryan Drury, Alyssa Monks and Jean-Pierre Roy alongside established artists sharing their views and methods. We were lucky to have the contributions of Steven Assael, Will Cotten, David Ebony, Natalie Frank, Mark Greenwold, Eric Fishchl, Bruce Gagnier, Hilary Harkness, Anne Harris, Trenton Doyle Hancock, F. Scott Hess, Jenny Saville, Irving Sandler, Ted Schmidt, Robert Taplin, Jerome Witkin, Eric White, and many others.

Larry: How did it come about?

Margaret: The New York Academy of Art asked me to project-manage a book Rizzoli was interested in doing about the school. Since it’s an academy that has been supported by both Andy Warhol and Prince Charles, and prides itself on both traditional methods, such as anatomy and indirect painting, and on contemporary discourse, I thought it would be compelling to take the long view and explore how and why the classical academic tradition has impacted the present state of figure-based art. I asked various knowledgeable people (who have in some way been involved in the school, teaching or visiting) to write on figurative topics. To mention a few, Lisa Bartolozzi’s essay on painting techniques shows how incessantly experimental painting has always been; Vincent Desiderio looks deeply into figurative painting’s ”technical narrative”; Alexi Worth’s hypothesizes “the invention of clumsiness” after photography hit the 19th c. painting world; Donald Kuspit describes some of the impact Freud had on the figure; Kurt Kauper explains kitsch and Jule Heffernan “the male gaze”; Laurie Hogin examines the politics of figurative painting; and John Jacobsmeyer and Nicola Verlato each discuss the meanings of spatial organization via perspective, the camera obscura, 3-D modeling, and cyberspace. With the supremacy of the internet today, the role photography and computers play can’t be denied.

The book doesn’t touch much on art springing from the modernist trajectory that reacted against that academic tradition -color-based, expressionist, or perceptual work. In my own paintings there is an emphasis on drawing but they are more modernist in their play between perceptual objectivity and surrealist whim.

Larry: Seeing your work and still life setup here in your studio greatly enhances the interview experience. I’ve long found your paintings fascinating but your work is much better in person, especially in color, surface and scale.

Margaret: It used to look better in slides, but over the years I’ve gotten much better with color and value and they look better “in person”. The images on-line look more cartoonish than they actually are, because texture doesn’t translate well on the web.

Larry: Also the scale; true of most images of paintings you see online. A tiny image becomes the same as a big one. You don’t see the net impact of that much paint in your face.

Margaret: People have said they thought my paintings were larger than they are; probably from how I toy with scale relationships, which is partly inspired by what I’m looking at, like architectural models, which were inspired by living in Rome for eight years among the monuments. Over the years I’ve collected various objects, stored by category. After I finish this still life of wooden objects I can get rid of some. The bizarre ones, or those most interesting to paint, are keepers. That wooden tree from Marshalls still has its price tag, so maybe I’ll return try to it.

Larry: Good plan! So, the store’s return date policy for the object influences how much time you get to work on the still life?

Margaret: I wish; that would be much more efficient than I am. In this composition I’ll probably wind up putting that odd wooden mirror on the bottom, so it will be both a still life and function as one of my “headworks” series, like Carmen Miranda Still Life (2009).

Larry: I see what you mean; I now see the self-portrait underneath.

Matthew Mattingly: Do you work the composition and drawing out on canvas, or from sketches?

Margaret: I rarely make more than idea sketches, but do draw it out in pencil on canvas first when working perceptually. At the NY Studio School I developed an appreciation for the process of painting, making a mark and then another in response, then questioning that – sort of “Giacometti meets Cezanne”. At its worst this way can lead you into a black hole. In grad school, as a perceptive critic Sidney Tillim pointed out, I was just making many paintings on one canvas, and Jake Berthot told me to read The Unknown Masterpiece by Balzac, which addresses obsession with process.

Larry: Can you explain more?

Margaret: Giacometti’s fetish of uncertainty can certainly lead to authentic depth. I remember the dark gloom over NYC when I visited the WTC site in fall of 2001. Right after that I saw a Giacometti show at MoMA, and was surprised it didn’t feel frivolous; his work probably in part reflected living in Europe during the world wars. But following purity can make you remove anything unnecessary and get carried away with “less-is-more” – or never finish, as Giacometti did not.

Ideally, it’s “two steps forward, one step back,” a forward progression. Textures build up richly this way, as in Cezanne, who never arrived cleverly or quickly at decisions, but almost sculpted, investigating decisions from different angles, so to speak. Sometimes he left non-objective marks that read like possibilities. I love the way his paintings are both solid and open. But I still can get locked into the present tense of process. Working from observation can bring you out of that loop because there is a perceptual “truth” you can always aim for.

An old school chum of mine, Julie Heffernan, called Shiny Still Life (2012) apotropaic – something that wards off evil. That’s basically the opposite of the inviting, rococo deep space Dave Hickey described in “The Invisible Dragon”. The compressed and congestive space in my paintings does push the viewer away, but also draws them in closer to investigate. I like the viewer’s eye to bounce around, which doesn’t gibe with Matisse’s directive for painting to feel like a “comfortable armchair for a tired businessman” – I wish it did because business people buy paintings!

Larry: One great thing about today’s art world is its diversity. Some like it simple, some complex. However, I think it’s tough if you’re a student trying to figure things out like what is good drawing or color, or if that’s even important. Are you teaching currently?

Margaret: I’ve been teaching at New York Academy of Art, Pratt, Montclair, and I’ll be teaching at U. of Virginia spring semester, and job-hunting.

Matthew: The organization of your painting is complex but it’s not chaotic at all. It’s actually highly organized. If you look at it for a while you can learn the pathways and algorithms for picking your way through complexity, which can then give you a way of seeing the complex world that’s right out there.

Margaret: Oh, I like that; makes me feel more normal. I’m very interested in politics, and our multi-faceted world.

Larry: I definitely see pathways and geometry that pull it all together. But you don’t seem bound by a particular compositional system. Each one of your paintings seems to explore structures unique to that painting. That’s very refreshing to see.

Margaret: My compositional spaces are shaped around my experience looking and painting, rather than from a believable deep space in which objects are placed. I’m only sadly just now reading Svetlana Alpers’ wonderful The Art of Describing (http://www.amazon.com/The-Art-Describing-Seventeenth-Century/dp/0226015130), about the more optical way space was composed in the North, vs. Italian Renaissance painting’s geometrical model. At Yale I took a class in Netherlandish painting (along with John Currin) but we were assigned Panofsky. At Washington U. in St. Louis, Amy Weiskopf and I took a lot of art history classes. Larry Lowick had us read Michael Baxandall’s great Painting and Experience in 15th Century Italy. http://www.amazon.com/Painting-Experience-Fifteenth-Century-Italy-Paperbacks/dp/019282144X I also read art history while living in Italy – I went there first on a Fulbright and then stayed eight years, teaching and painting.

Larry: I read that Piero della Francesca, when his eyesight was failing in the last ten years of his life, wrote a whole treatise on perspective and mathematics.

Margaret: Yes, which business students studied to better understand quantities, for trading purposes. Baxandall describes how, before “universal” systems of measurement were standardized, science and art were fairly equally advanced as ways of expressing knowledge of the world. So objects like Piero’s chalice had intellectual appeal in Renaissance paintings. Alpers also shows this in Northern painting, which didn’t use strictly-pointed perspective, but engaged the inquiring, human eye, rather than relating everything to the absolutes of math, or the all-seeing eye of God.

Larry: The tipping up of the picture plane in your work, which flattens the space, relates to Northern Renaissance painting

Margaret: Yes, and to Cubism. I like foreshortening because it suggests deep space, but also lets flat shapes assert the picture plane. I suspect, having grown up in the middle of ten children, that I grew accustomed to constant motion in my visual frame. I generally find visual situations that are complicated and dense appealing. After I saw Glengarry Glen Ross and The Player I loved the way complexity arrives at harmony in them so much I went back and saw them again the next day. I enjoy looking at paintings with deep space, but it’s never been something I’m consistently interested in. Scott Noel, who I also went to undergrad school with, suggested I put more space around things. I have gone through periods doing that, but wind up squishing things in tight spaces.

Larry: The main thing is, does it work for your paintings, and is it successful?

Matthew: I think there are believable spaces in Shiny Still Life, but they are small spaces. The way the little bathtub thing is in front of whatever the hell that thing is –

Margaret: – a duck cooker I bought in a flea market in Rome –

Matthew: – there’s definitely accessible and believable space. You probably couldn’t fit your finger in there, but you could fit a piece of cardboard in there. You know that between the whale’s tail and the bathtub, there’s a little bit more space. There’s no problem of space; there’s plenty of space. It’s just miniature space.

Margaret: That’s what I want for the viewer – at first you’re overwhelmed, then your eye experiences everything intimately; maybe that’s how I see the world. That echoes the way I prefer to be close to what I’m painting so stereoscopic vision is activated, and I fully see around things. I’m also very near-sighted, so there’s that.

Larry: I’m curious if you ever think about a hierarchy of highlights in a painting, or naturalistic light qualities and the degrees of the reflectiveness of things, and such?

Margaret: I’m very sensitive to light in the real world but in my paintings it’s secondary to the description of form and space. I follow it closely for certain color relationships or to create textural illusion, like metallic surfaces, but my sense of light is largely conceptual and circumstantial.

Larry: I really admire Mom’s Accordian (2013). Tell me how this came about. It seems more straightforwardly perceptual.

Margaret: I inherited this object from my mother after she died a few years ago, and wanted to do an homage. I set it up under a blue light but didn’t really have enough space in my studio to control the viewing light. I also had to finish it for a deadline for a Zeuxis show, so I painted it at all hours with daylight and artificial light, so the light is less naturalistic. The abalone was fun to paint.

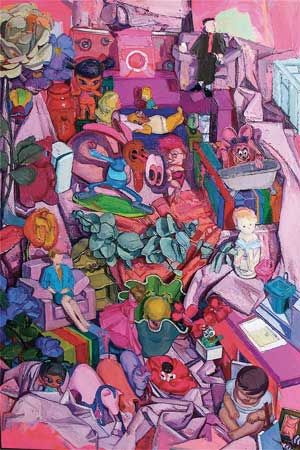

Larry: Tell me what’s going on in terms of the narrative in this large boardwalk, Atlantic City painting. What led to it?

Margaret: Living in Atlantic City for four years was such a trip. It reminded me of an R. Crumb cartoon because so many of the visitors looked dressed for a bad outfit contest. You see all the clichés, people passed out outside casinos from a bender, drinking and gambling. It’s a very wacky, but very friendly, place. Once while waiting for an early bus to New York, a policeman told passengers about how his feet got really sore near the end of the night shift until he started getting pedicures. It’s hard to imagine that conversation happening in New York.

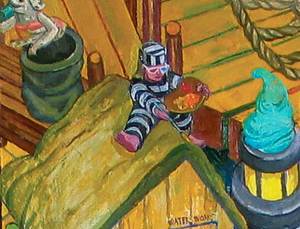

In Follow the Money (2010) Uncle Moneybags is getting away by implied helicopter (inspired by the Yogi Bear cartoon), but everybody else is having fun and doesn’t notice that the piggy-bank is about to surf over the edge, or the impending flood.

Matthew: That’s you in the prison uniform with 3D glasses painting the whole thing? Cool.

Larry: So, what does that mean? It caught my eye too. Wow, that’s different.

Margaret: Maybe that I’m the only one seeing things in 3D? That’s a space joke – kind of like the bit of extremely deep (looking from outer) space in Call Me Marge (2004), which is otherwise pretty flat. That’s mostly synthetically painted – I observed the head, but based the rest on where appropriation led; R. Crumb, Guston, Hopper, The Simpsons, Cezanne, and – what is that from?

Larry: The Little Engine That Could, right? Would there be a sequential way to read these, or does the viewer make up their own story while looking at the painting?

Margaret: I’m leading the way with the big blue shape and yellows moving throughout, but the viewer can make their own subjective way. Obviously all the “headstuff” has psychological implications. My compositions, beyond an initial design, form intuitively, part to part – like a surrealist. Sideshow (2013) has perceptual moments, but most parts, like the Monopoly board and the boat, are invented. I left some areas sketchy, which play off the thornier areas I reworked.

Larry: I’m curious how you respond to someone like Gregory Gillespie, another person who combined surrealism with perceptual work.

Margaret: I like his early Italianate self-portraits, but am otherwise not crazy about his color or the heavy reference to the photograph. Peter Blume or George Tooker interest me more. Better yet, Edwin Dickinson, who uses the Cezanne-Giacometti thing somewhat.

Matthew: Can you talk about the Ratfink? Haven’t thought about him since about 1966.

Margaret: I’ve put him in several paintings; fun to paint and a fond childhood memory, along with Basil Wolverton bubble gum cards. I like the mixture of serious technique and silly motif. He appears in What We Worry? (2009) too with Alfred E. Neuman on a soapbox, and others on the boardwalk. After a while you notice a tsunami entering the casino. This situation has an apocalyptic end, but it’s also fun so people will enjoy looking at it.

Larry: You often seem on the verge of a political statement but then thwart it with whimsical, cartoony elements. I’m always puzzled with the question of art as a realm for politics.

Margaret: Picasso said all art is political. In “The Figure” I wrote an essay about how history painting has morphed in response to socio-political and technical changes, including the Industrial Revolution, photography, and the Cold War. In the 20th c., after its profound corruption by Hitler and its adoption by authoritarian governments, heroic figuration was viewed suspiciously in “the free world” as reactionary. Eventually any figurative painting was suspect as potentially colonialist or oppressive in some way. After the western art capitol moved from Paris to New York because of the wars, critics like Greenberg posed American abstraction against Socialist Realism, and the standpoint of Social Realism became confused. But the Cold War notion that abstract art is a-political is too purist; any style of art can be exploited – or be academic. AbEx meant to its promoters (not to its creators) the freedoms promoted by capitalism. Who patronizes art and shapes cultural values has always mattered. It’s interesting to think about why extremely wealthy still buy art; it speaks to its spiritual value.

Matthew: There are some great technical realists like Jacob Collins who are in effect reactionary – back to the age of Bouguereau, as though the twentieth century didn’t happen, feminism or communism or anything, really. Nothing threatens assumed ownership of the land in landscapes; female nudes have a tasteful “come hither” look, and males show off their big muscles.

Larry: Some of the current crop of neoclassical painters coming out of the atelier seem to want to get back to a world where issues like racism and sexism weren’t discussed. The French Academy went far beyond technique. It defined beauty, what could be considered art.

Margaret: It’s ironic that those people would probably be very opposed to Greenberg’s advocacy of pure abstract painting, yet in a sense they’re heeding his conclusion, retreating from the world in an “art for art’s sake” way.

Larry: But isn’t making a political painting like waving a banner at a rally of like-minded people? Guernica isn’t going to convince anyone who didn’t already agree that war is evil, it’s just an affirmation that the world needs changing. Is that enough?

Margaret: The nice thing about museums is that everybody goes there, artists and “normal” people. Some who see Guernica might only think about Picasso, but others might actually google that event, an opportunity for the Nazis to show off their fire-power. Art can remind us of the depths to which people can go; it gives us the courage to act.

Matthew: The tapestry of “Guernica” was in the room that UN delegates passed through to remind them war is horrible, so the Bush administration had it covered up in 2003 before the invasion of Iraq was discussed. That’s how powerful that painting is.

Larry: In a lot of recent political painting the ideas may be interesting but often the way it’s painted or visually communicates is lacking.

Margaret: Lots of postmodern, political art is not nearly as exciting as that done by the Constructivists a hundred years ago.

Larry: Our lives are often distracted and can interfere with giving a full commitment to the art work. Painting should strive to equal the depth, intensity and craft of the masters.

Matthew: Regarding the idea of finding the path of complexity, and teaching people a kind of dance, as it were: Promoting a form of thinking that’s not just binary, not just oppositional, and not just “going for the most obvious enemy to attack” could be a kind of effective political way of being.

Margaret: That’s really interesting – let’s write a manifesto! – that painting can teach people to think in more complicated ways, making them more effective agents in the world. Beyond dialectical.

Matthew: It’s trilectical, multi-lectical. What happens in the end is determined by all these things pushing at each other; that’s what the world has to deal with. People tend to lump everything into the good guys and the bad guys –

Margaret: – the Cold War mindset, black and white thinking. Lawrence Weschler gave an interesting talk last year suggesting that the knowledge of big events and of their iconic photographic images in “Life” magazine and newspapers may have generally or unconsciously influenced artists: Hiroshima on Pollack, the moon landing on Rothko. These possibilities don’t fit the formalist paradigm, but they were in the air.

Matthew: Pollock isn’t about destruction as much as energy, which in a sense relates to Hiroshima. Pollocks aren’t chaotic; they are organically organized. Pollack was saying, “This is my life force in the purest form I can give you.”

Larry: Pollack explored the ideas – thinking through paint – of Freud and Jung. A strong political painting may have also started with a now outdated idea or event, but the inspiration for the formal structure is still meaningful.

Margaret: Historians of the future, if they/we exist, will consider what was going on in the world when there was this big 20th c. divide between figuration and abstraction, and technology was becoming an uber-behemoth.

Matthew: It all comes from somewhere… Crumb was about popular culture, but he got his stuff from Renaissance drawings; cross-hatching. The zeitgeist is eventually created by a few influential artists who start the ball rolling. That’s your job as an artist, to aspire to become one of those people.

Margaret McCann’s book “The Figure can be purchased from this Amazon.com link – (if you buy this book from this link a tiny percentage will go to help Painting Perceptions)

Thank you for this wide-roaming, fluid and free-floating discussion. I’m looking forward to reading and looking at”The Figure.” I enjoyed your comments on Svetlana Alpers and Michael Baxandall. These two authors have written a fascinating book, “Tiepolo and the Pictorial Intelligence,” which was a huge influence on my studio practice back in the late 90s’.

Your working process, with layered pictorial spaces, figuration and voluminous drapery is similar conceptually to Tiepolo’s working out of a shaping mind.

(Svetlana Alpers & Michael Baxandall, Tiepolo and the Pictorial Intelligence, Page 45:)

“The mind plays with images, and they can take many different forms; forms can drift between two and three dimensions before full recognition; they are curiously medium-free; they can move in slow motion, a kind of suspension of animation; the array displays a coherence, but is strange or bizarre; time is not an issue, it is as if something past were made present; it is characteristically hard to recall.”

Thanks again.

Thanks for the thoughtful response – I will check out that book! I just finished reading Norman Bryson’s excellent “Looking at the Overlooked” – he really understands how to look at paintings! – highly recommended.

Well done!