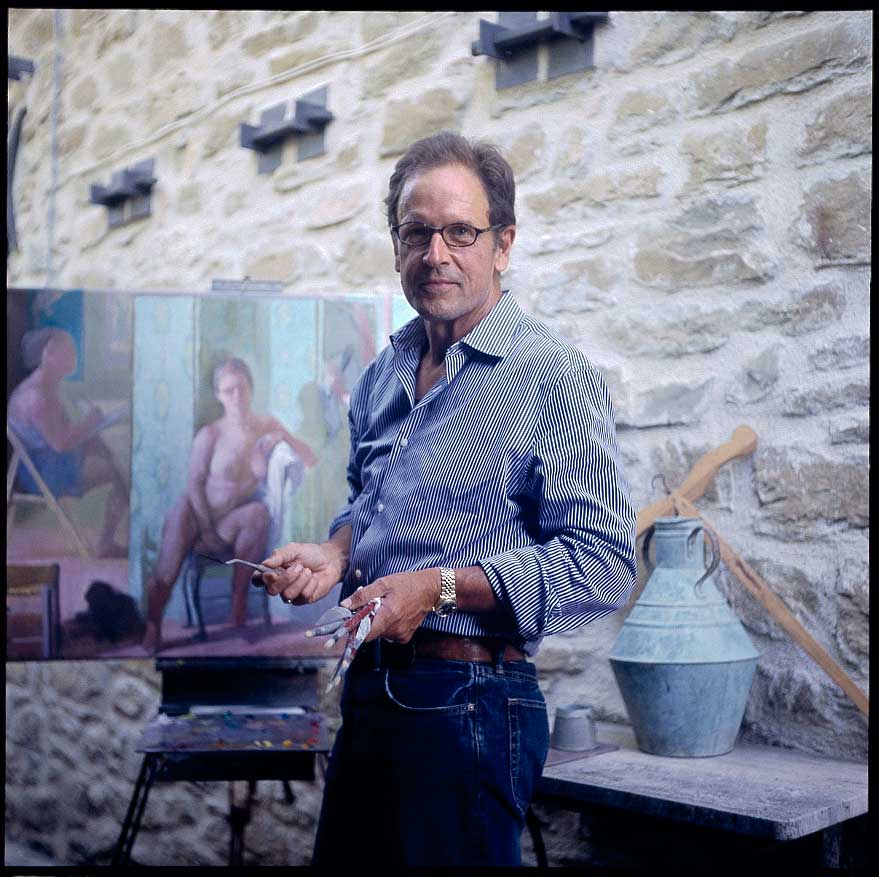

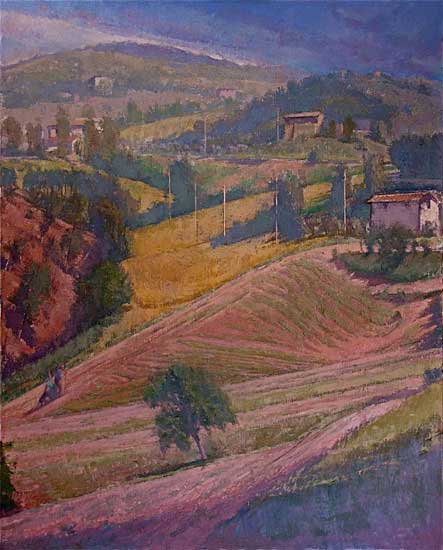

Langdon Quin, a highly respected painter living in both Italy and upstate New York is having an exhibition of recent landscapes at The Painting Center from March 31–April 25, 2015.

Quin has exhibited widely, both nationally and internationally. Since receiving his MFA in Painting from Yale University in 1976. He is the recipient of many awards including a Fulbright Fellowship, a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Grant, a National Endowment for the Arts grant, and two Ingram Merrill Foundation grants. He is also a member of the National Academy of Design in New York City.

His work is in prominent public and private collections both here and abroad. In addition, he has had a distinguished academic career teaching and is currently a Professor Emeritus of Painting and Drawing at the University of New Hampshire.

Quin has had numerous one person shows in galleries on both the east and west coasts. These have included The Thomas Deans Fine Art in Atlanta , the Kraushaar Galleries, Robert Schoelkopf Gallery, New York, Alpha Gallery, Boston and Hackett Freedman Gallery, San Francisco.

I am very grateful to Langdon Quin for spending the time and energy in talking with me about his background, process and thoughts on painting during our Skype call from his home in Italy.

Larry Groff: The Painting Center has an essay about your upcoming show on their website says that you recalled vividly that Fairfield Porter “likened painting to poetry in urging the consideration of “particularization of experience” Porter also said along this line of thinking: “You can only buck generalities by attention to fact,” Porter continued. “So aesthetics is what connects one to matters of fact. It is anti-ideal, it is materialistic. It implies no approval, but respect for things as they are.” I’m curious to hear what you might have to say about how this thought has affected you.

Langdon Quin: Yes, Porter gave a talk at Yale that was, I think, taken from an essay he published “Technology and Artistic Perception” in the American Scholar journal; this was shortly before he died, so it later seemed to me a summing up of his idea about why painting was important in an age where everything was changing by the minute.

At that point it was 1975, and it seemed, in retrospect, just incredibly prescient that he could identify and insist on a place for painting likening that activity to poetry—both forms filling a need has to do with specifying the particular experience that people have in relation to something seen, felt, remembered, imagined, whatever it was, because technology and its generalizing tendencies was eradicating those important subtleties.

The thing I remember distinctly was this rather simple analogy that worked for me, and stays in my head: He said, “Most of you here [but I wasn’t one of them, because I was/am old enough] are too young to remember a soda fountain, a place where you would sit on a stool and somebody would mix a Coca-Cola for you with a certain amount of seltzer and a certain amount of syrup, and that became your drink. So, it was particular to that place and one would perhaps prefer one soda fountain to another because of the way they mixed the Coke, or made a cherry Coke or some other variation.

Then, Coke became bottled, and in doing so it became uniform, and it all tasted the same. So, it just stays in my mind as a kind of metaphor about Porter and his identification of the primacy, and importance, he placed on distinct material realities, that were worth celebrating in at time when new technology was seeking to blur such distinctions.

it gave me a way of understanding Porter’s work, because he just wanted to be terribly specific about not just what he was seeing, but also what he was feeling about the things he was seeing. Like all of us, he made stronger paintings as well as making some pretty ordinary paintings, but this intent of his to particularize experience seems most clear in the late work. In these, it seemed there was something inspired in a kind of materialistic identification with the paint in reference to whatever he painted, not just to make it illusionistic; but to make it feel like the place, something that was imbued with another layer of physicality and intervention, made manifest in the paint handling itself.

I’ll say that. I’ve always been drawn to people like Corot and French painting of the 19th century and other periods. The 19th century French model for me of late however is less Corot, than Courbet. Courbet’s landscapes look like observed places, they breathe light and air, but they also have a transformative power that’s palpable. So that’s the kind of landscape painting, that I’m admiring these days; I see it in Courbet, I see it in Balthus’s Chassy paintings, I see it in Hodler, I see it in Soutine, Bonnard, Morandi, and others. Our conversation is prompted by my landscape show coming up, but I do paint figures and still lives as well.

Larry Groff: What lead you to become a painter and what were your early years like as a student and young artist?

Langdon Quin: I had the benefit of a wonderful high school teacher who passed away some years ago. His legacy is felt today at the school, in the form of the gallery that is dedicated in his name and memory, the Mark Potter Gallery at The Taft School. It hosts terrific shows in the school’s beautiful space.

More than anything, I think he was a model for me as a way to live a life and to embrace all kinds of experience. I was swept up with my enthusiasm for him and his passion about life’s possibilities. It was as simple as that. I was a suburban kid from Atlanta, and I had won a scholarship from some Atlanta people to go to that boarding school in Connecticut. No one in my family that I can think of had any artistic inclinations. So, this teacher was the person that got me moving early on in the direction I took towards becoming a painter.

Like most of us, as a child I showed some propensity or talent for drawing and doing things in classes that, from third grade up, sooner or later got recognized. But this certainly didn’t make me feel like I could, or would want to become an artist.

I’m wasting too much time telling you a perfectly, as I say, ordinary story, but Mark was important to me. Fast forwarding quite a bit to 1973, Caren Canier (my wife) and I, without knowing each other previously, met in a summer program at The Tanglewood Institute in Lenox, Massachusetts, where we studied with Gabriel Laderman.

We had an intense, long summer with Gabriel in our faces for a couple of months. There was really a big door that opened for me there, thanks to his auspices. I am forever indebted to Gabriel. We became friends later, and I’m still in touch with his children. Gabriel died a couple of years ago, but he was a wonderful teacher and very important to me. I certainly would count him as a major influence.

Without totally discouraging me, he made me realize that I really didn’t know anything, and that I had a lot of catching up to do. I remember distinctly,(I was 25 at the time) when. he said, “You should go back to school and enroll at KCAI. ” In those years, he was very enthusiastic about the teaching of Stanley Lewis, Wilbur Niewald, Lester Goldman, and other people at the Kansas City Art Institute. He said, “You should go back to Kansas City and start over.” I said, “I’m 25. I’m not going to start over as an undergraduate.” I guess he was okay with that, but he may have been right with that recommendation.

Larry Groff: I’ve heard that the painter William Bailey has been an important mentor and friend. Can you say something about what that has meant to you and your work? Who have been some other important figures for you?

Langdon Quin: Eventually, I was accepted at the Yale Graduate program and I studied there with a number of people, including William Bailey.

Bill and I are very close friends. He was enormously important to me. I would say that he gave me an understanding of color theory, based on Albers, that I hadn’t really understood in spite of some study.

My understanding of color was, up until that point, completely intuitive. I could mix warm and cool, but I didn’t know about the qualities of color juxtapositions and how they can be weighted against each other abstractly and also drawn from observable phenomena. Bill really gave me more than a clue—he gave me a vision of the way that can happen and be used expressively. His belief in the importance of drawing was also very meaningful to me.

My other teachers there, to whom I am also indebted, were Gretna Campbell , Bernard Chaet, and Lester Johnson. This group, together with Gabriel, I would say, were the significant influences as I was developing as a student. I later came to know James Weeks very well, when he taught at Boston University. He and I shared an office, in fact. I was an adjunct instructor at the time, and he was a full-time professor at Boston University. I taught at BU for five years, and throughout my time teaching there we were good friends and quite close.

Larry Groff: Where you at BU when Philip Guston taught there or he had already passed away?

Langdon Quin: My wife, Caren, was a grad student there finishing in 1976 . She had been an undergrad at Cornell and then went to BU. She was very close to Guston and counts him as one of a couple of very important teachers.

I met him on a number of occasions, when he would come back to Boston from Woodstock… At that point, he was pretty much cutting the cord with BU and would appear a couple of times a year to do a critique or a conversation with people. He was not present on a regular basis in the late 70’s. I spoke to him a couple times in those last years before he died in 1980. But, I won’t say that any influence came from a direct personal connection.

My years in Boston were good years, but I think of them especially positively because of my association with Jim Weeks. He was a wonderful man, and the things that he did in his work I came to understand and appreciate in subsequent years. I looked at Jim’s work and thought about the things he said, and later decided, “He was right!” It’s a shame that he’s a neglected painter, at least in terms of the public awareness of him.

Larry Groff: What was some of the things that you remember the most that he might’ve said that was important to you, in terms of moving your work forward? Is there anything in particular he would say?

Langdon Quin: Well, if I could make a connection in terms of “Boston” people, and what they meant to me, I’ll say that Jim’ s idea of spatial compression with shifting play between two and three dimensions is one of the things I also admired in Guston. Everybody these days seems to love Philip Guston. Unfortunately, he’s been the progenitor of a particular kind of cartoony imagery one sees a lot of today, but I think the thing that’s missing in most of the people’s understanding of his contribution is that his paintings had a surface tension that was so considered and so taut. One really feels the heft and pressure of the forms he made and their juxtaposition. The subject matter has an offhand look to it, but it’s really quite charged in formal terms. That was true of Weeks, as well. Weeks’ paintings, to me, had this wonderful surface tension. I mean, the way he would compress two and three-dimensional things together, and then separate them and relax them, open them up, close them down. It’s not a language I really understood at the time, but I’ve come to understand it better. That is the way it works with good teachers, I think—it takes a while to get what they are talking about and trying to do in their work.

When you’re first hearing something from someone you admire, you’re trying to get it from the back of your head to the front of your head. so you can use it .But you don’t quite get it because that takes some time, and when finally you do start get it, you can’t thank them, because they’re gone! Nonetheless, I feel that way about Jim Weeks and Gabriel, certainly, who’ve both passed on. I think they were both terrific artists and educators.

Larry Groff: Does William Bailey’s involvement with classical arrangements and composition from a modernistic perspective have much influence on you? I think I can see similar concerns with a more classical sensibility in your compositions.

Langdon Quin: The question is of great interest to me, Larry. But, in a way, I can’t comment intelligently. I suppose Bill and I do share a classicizing instinct, but I don’t really know what that looks like. I mean, Bill’s not a landscape painter, and I am, and surely the ideas about color and drawing he passed along to me have found their way into my landscapes. We’re all drawn to people that have a form sense that we identify with and admire. In Bill’s case, his sense of interval, pace and arrangement, exist in worlds he makes up. On the other hand, just about everything I do is grounded in observation. Nonetheless, his form sense is something I really respond to, and maybe I reflect something of that influence in my apprehension of landscape motifs. My work, I don’t think, looks so much like his. But, I take it as a compliment however; that you think there’s an observable connection. I’m thankful for my training with him and greatly admire his accomplishment.

Larry Groff: Not the outward appearance, I meant more that what you might select to paint or how you might place emphasis on the horizontality and intervals has a classical feel to the composition at times. Of course the subject matter’s completely different. Like you said how color affects his. I think of his color as very subtle and subdued. His color is deeply felt and wonderful, but completely different than yours. I wouldn’t easily see a connection of his color to yours at all until you brought it up.

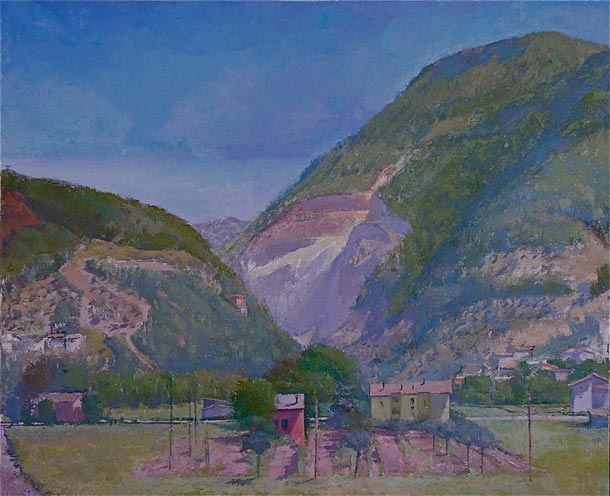

Langdon Quin: No, I think Bill probably likes aspects of my work and appreciates our shared history and respect for particular painters. But I’d guess he thinks my color is in a very saturated range that doesn’t always work. It may be that I’m trying to reconcile things that he’s tried to reconcile as well, but with a totally different palette and approach. I’m interested in the possibilities for more saturated color in the landscape, more in the spirit of Bonnard than say, Corot, both of whom I consider great colorists. But, I mean, compared to everything else that is out there in the art world that passes as experiment and color, my efforts fall in a pretty narrow traditional range, and that is fine with me.

Larry Groff: : Can you talk about your process in painting the landscape? Does it differ significantly from how you go about making your figurative work and still lifes?

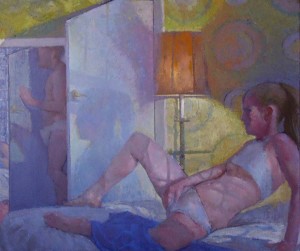

Langdon Quin: I think people think of me as a landscape painter but I do make other paintings. The ideas for those paintings have a different, slower-forming genesis. But in my day-to-day experience, the landscape seems to intrude most and calls out more for its recognition and observation.

Whenever I make a painting of any kind, whether it’s landscape, figure or still life, I have to have seen that situation in the world. I have to have experienced it. Even if it’s just momentarily, even if it’s just a drive- by event; if I have seen it, then I can believe it and I can develop it, or try to, at least. That pertains to the landscape, figure, still life, whatever. It all starts from there.

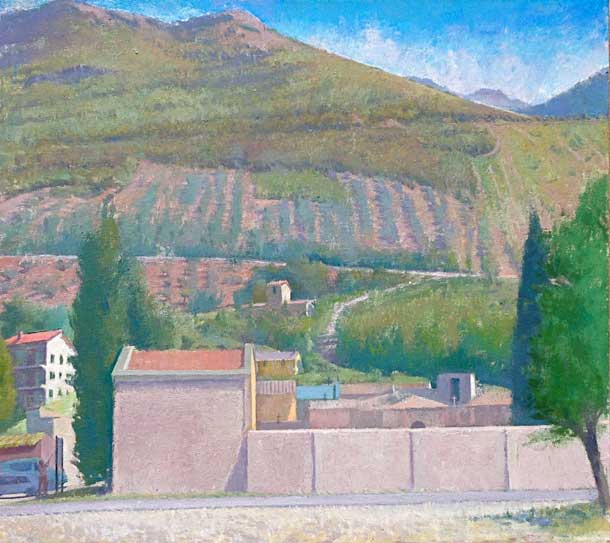

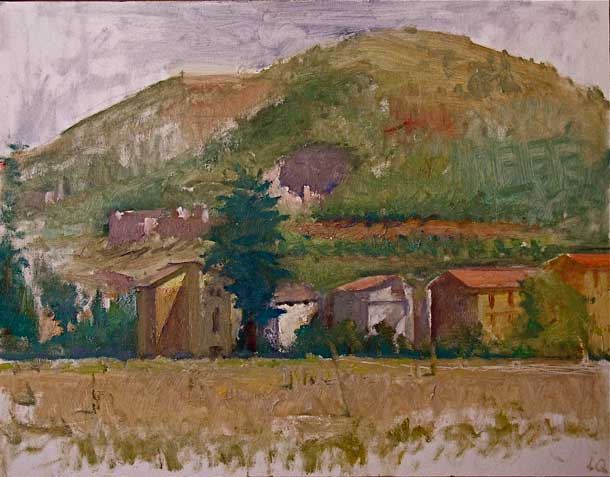

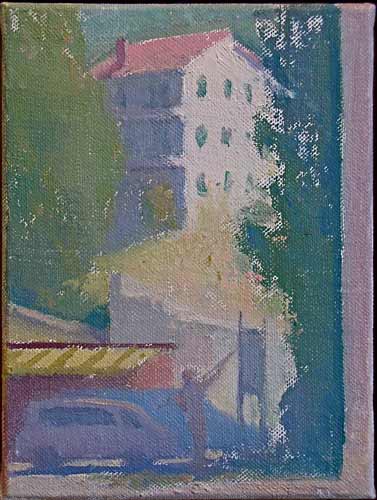

But returning to your question about my landscape process, I start from small oil studies done on the spot. I have a few French easels and I just set them up. I do quick paintings and drawings. Then my practice these days, certainly for a landscape, is to bring those things back and develop larger paintings in the studio from them.

What could be more traditional than that? It’s so historical. That’s what just about everybody I admire did. It’s not set in stone; it just seems to work most easily like that. I had up until the last 10 years or so, occasionally set up big canvases outside and tied them down with guy wires and things. I just don’t care to do that anymore. Too much bother!

I enjoy painting more if I can develop pictures in the studio based on plein air sketches and then make the compositional choices and color changes that the painting suggests to me. So, at that point, it’s not what is dictated by allegiance the actual motif, and studies from it, but what happens after those initial encounters.

I want keep the life and quality of the motif alive, but I don’t want to be tethered to it. I want to be able to change it and move things around. I’m more of a studio painter in that sense, than I used to be in my 30s and 40s.

Larry Groff: So you don’t feel restricted by the particulars of the scene that you’re painting in the studio? If a house were in one location, you’d be willing to move it to an entirely different place if you wanted?

Langdon Quin: It usually doesn’t amount to a change as big as that. I don’t make dramatic changes in the alignment of forms so much as the color and the importance of different forms, the elaboration of the form. They pretty much stay in the same place. The drawing and the positioning of forms is more or less what I start off with. It usually stays that way, although I do make changes like that sometimes.

The main changes have to do with the palette and the kind of articulation of passages, whether they’re pronounced or diminished or played up and down in terms of their importance. But it’s all grounded in a set of things that I’ve seen and then manipulate.

Certainly this is accurate with regard to landscape; the figure paintings are a different thing. The show coming up is all landscape. It’s more appropriate I guess that I talk to you about that.

Larry Groff: Feel free to talk about whatever is important to you. I was asking you kind of more all about landscape because of the show, but I love your other work just as much. In particular I was admiring your still lifes. I was looking at your catalog again and I’d forgotten what incredible still lifes… Like the still life with 2 tables from 2004, a fabulous painting.

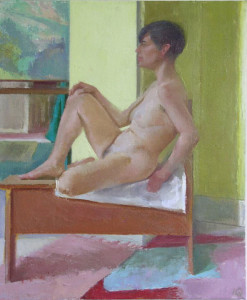

Langdon Quin: Thank you. The still life… I would say of the 3 forms, if we can simplify it and say the 3 forms, that the still lives are the most dependent on direct observation. When I paint a still life I’m sitting there in front of it, and stay put in front of it pretty much from start to finish.

When I’m painting a landscape, I start them outside. I draw, paint from the motif, I bring them in and they become studio paintings. If I’m doing a figure painting, it’s a similar thing. I’ll paint from a figure. I’ll make a figure painting, a little figure painting, then I’ll think, “oh, well that one would look like something possible if I could put it with this other figure painting that I’ve also done from observation, and then some grouping and/or narrative might emerge in pairing the two”.

The two of them then start to take off as a combination that becomes complete invention. I don’t have the same models back or anything like that. It becomes another studio enterprise altogether. They’re slower to develop and I don’t think I’m very good at it, in the sense that I can’t resolve them (figure compositions) as comfortably or happily as other things.

I’m a little more tentative about those things and their successes or failures. After this show, I want to paint more still lives and get back to some figure painting ideas.

Larry Groff: I loved your Danaë painting, a fairly recent figure composition, I think. Another incredible painting.

Langdon Quin: That’s a weird painting. I don’t think of it as being terribly successful, but something I got very involved with. It was almost completely invented. I had a model at a certain point but the model wasn’t doing what you see in that picture. It was all-associative. When I thought about all the images, whether Titian, Correggio or the many other great Danaë paintings that artists have made, I wondered, what if Danaë was angry at being disturbed when Zeus appeared in whatever form he chose, and she was irritated and refusing him rather than acquiescing? It was just a kind of whimsical departure from the traditional idea. It was based on some figure paintings I had done from models but then changed dramatically. I don’t know about that picture. I don’t want that to be my last figure statement.

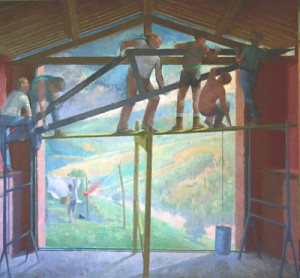

But another one that you might see on the website is called La Capriata, which is a group of 6 men perched on some precarious scaffolding, working on a construction project. That was something I actually saw, and I looked at it and said, “That’s a painting!,” After I watched them, I immediately sat down and made some drawings from memory… The workers disappeared later, of course, They’d gone home for the day, but the memory of their grouping against the sky was very intense.

I developed that out of a very crisp, clear memory. It wasn’t the fantasy that the Danaë painting was. It was based on a very compelling, searing visual thing that I saw and I thought, again, going back to what I said earlier—If I’ve seen it then I can believe it. I know it happened. Then I can think about developing it.

The times like the Danaë painting where I haven’t really seen that situation. I don’t really totally believe in the fiction nor my process in picturing it. Those are the ones I’m more tentative about because, I don’t know, they weren’t grounded in something seen, something observed.

Whether it’s still life or figures or landscape, I feel most comfortable if I initiate something from direct experience. Those are the things I can get behind because I know they exist or existed.

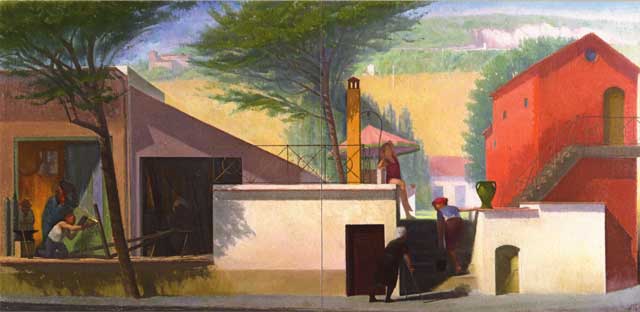

Larry Groff: You had an earlier painting, the La Bottega, the family portrait that was on the cover of your catalog. That seemed like it probably involved this painting from memory yet it still seems very specific.

Langdon Quin: That’s a good example, as those are all people I know. That’s a place that I know very well. I know what everything looks like there. I have seen those people go up and down those steps and I’ve seen those people working in the background.

The development of that image perpetuated a kind of painting experience because it was informed by an awareness of those people and their interaction with their environment. Also, I could re-visit the place, just drive over there with my car, sit there and say, “Oh yeah. That looks like this. That looks like that.” Go back, make a few drawings, and keep working on it. It was all part of an observable place and time, even though the picture was a studio painting.

Larry Groff: I curious to hear how you might reference other art in your work, especially the color. Some of the color in your landscapes brings to mind early renaissance Italian fresco painting to me. Is that something you think about or is it more just your personal color sensibility? Or has it more to do with your location that is particular to Umbria? I’m hoping you could talk about the relationship of your color and other art.

Langdon Quin: Well, I remember many years ago somebody saying to me, “Your palette is so unique.” I thought, really? I didn’t feel that. I’m not at all objective, or aware of that. I can’t answer your question except to say that whatever affinities may appear in my palette or my view of color or how color may be operating, they’re not conscious or calculated on my part. I’m not trying to mimic someone else. The things I do with my own palette and the things I admire in painting are wedded in some way that I’m just not really aware of.

Larry Groff: It’s not a conscious process then?

Langdon Quin: Not at all.

Larry Groff: I suspect that for most people, it’s just their sensibility or personality that comes through without their control. But perhaps what makes up your personality comes out of your love for particular kinds of situations and particular types of art.

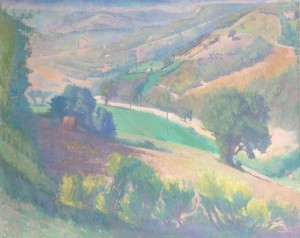

Langdon Quin: I’m impressed by the luminosity and the intensity of light in lots of different kinds of painting. French painting, but also Italian painting. The idea of a painting giving off light enchants me. I‘ve read of Alex Katz asking the same kind of question—how much can the painting act as a container of light, how much light can it emit? In terms of the painting’s luminosity, in terms of its color’s expressive suggestion? How much can it push out from the wall? Those are things I really like about certain painters.

Again, Balthus comes to mind. Especially the paintings from his chateau in Chassy, and his other 1950s works. Bonnard is another major figure to me. He makes a painting glow. I want my painting to glow and I want them to contain a light. They need to be tonal but they also need to be luminous in terms of the modulations between their tonalities and their local color identifications.

I suppose this is a late modernist idea about color. It’s not a 19th century or earlier idea about a directed light moving through time, space and different narrative moments within the frame of a single image. I want the whole thing to be materialized and a container of light that acts at once. This is a modernist idea even if not many people in our postmodern art world value that, or see it as such.

I would say that in the last 20 years or so, the tonalities of my paintings have gotten much lighter. That effort has been purposeful—to make the paintings as positive, meaning pushing away from the wall, as they can be.

Larry Groff: Many of your landscapes have an open, scrubby quality to the brush strokes that lets the white ground of the canvas show through, at least from what I can see on the computer screen. I’m hoping you might say something about this.

Langdon Quin: I don’t paint on toned canvases. I start a painting on a primed white canvas, lead primed white canvas. I really believe that referencing the whiteness of the canvas is important to keeping the glow of the paint present because the more you paint on them, the darker pictures get naturally. They run into all their problems with muddiness, chalkiness, etc.

If you start on a white canvas, you’re constantly referencing the white canvas. I purposely leave a piece of white canvas available somewhere in the painting so I can keep cueing things to that piece of white canvas. Keeping the value structure up because if it starts to get too dark then I know I’m in trouble.

I never paint on a toned canvas. I think it’s a mistake. I was a teacher for many years; I wouldn’t let students tone their canvases. I said, “Start with a white canvas. Always. Divide it and refer to the white as a moment on the scale of light to dark. Use that as a key of how to develop the rest of it.”

Larry Groff: Do you work fairly thin, thin paint, to utilize the transparency of the paint over the white ground to get luminosity?

Langdon Quin: The rougher the canvas, the better to me, whether it’s a quick painting or a long painting. I think that the roughness of the canvas enables me to create accidents that then suggest things and I can follow the suggestion and run with it for a while.

In answer to your question, I do start things pretty thinly, but just to lay them in. Then I drop the paintbrush and I pick up the palette knife and I start just trying to build a surface that feels right. That doesn’t mean that it stays that way. I scrape it down, build it up, scrape it down again, build it up. That activity of going back and forth between thick and thin is part of the process.

There’s a painting, a very large landscape I did a number of years back that I worked on for a long time. There are places in it where the paint is quite thick and there are other places where bare canvas is showing. It stayed bare in those places only because it keeps feeling right in terms of its value and strength in a color way.

Not that I’m trying to, I don’t know, trying to make a quilt of thick and thin paint at all. It doesn’t matter to me if it’s thick or thin. If it works, it works. I do enjoy the process of building up the paint and tearing it down, building it up again, tearing it down. Seeing what all those scumbles can come up with. That’s the pleasure, especially in studio painting

Larry Groff: You work on canvas, not linen generally. Is that the case?

Langdon Quin: It’s all linen.

Larry Groff: On the catalog it said canvas. I was…

Langdon Quin: I say canvas but I use the term loosely. It’s all linen. I don’t paint on cotton duck anymore. I haven’t for years. Although, I have no objection to it. Good cotton duck is certainly better than bad linen. For the most part I use linen, and I used buy Utrecht linen. They made/imported a kind of linen I loved. But they don’t anymore. I buy my linen here in Italy for the most part, and use it here and back in NY. My practice really these days has to do with starting paintings here in Italy and then taking them back to the U.S., I roll things up, I take them back, I work on them there, I bring them back, I go back and forth with tubes under my arms all the time.

My paintings rarely get more than 4×5 feet because that’s all I can carry on a plane. Oftentimes they’re a lot smaller, but that’s about as big as they get. Sometimes I’ve done paintings joining two side-by-side 4×5 panels that are more comfortably broken down and rolled up.. I’m moving back and forth between 2 different places. That’s my life these days and that’s what I do. Tubes and more tubes!

The linen I prefer is rough and has a lot of imperfection in it. That’s what I like. I like it almost like sack cloth. Just something that creates plenty of accidents as I put the paint on it and play with it.

Larry Groff: Do you, this is an aside really, for my own problem. I have been using linen most of my life, too. Lately I’m getting a little disenchanted with it because I have so many problems with it sagging out here. You would think it’s relatively dry, it would be less of a problem. It’ll be tight as a drum, it’ll be perfect, and then a few days later I’ll come and it will be all sagging and waving like a flag. It drives me crazy.

Langdon Quin: Yeah, I know. I know. It’s a problem certainly. That’s one of the reasons I stopped buying stuff from Utrecht, I would get linen that the warp and the weft, I don’t know what it was, they weren’t the same fibers or something. I would get all these little bows around the edges of the canvas. I said, “Screw this. I’m not going to buy their stuff anymore.”

I eventually just stopped. Yeah, linen is always subject to humidity and other things. I have a guy in Queens, New York who makes stretchers for me. He’s great, prompt and careful. His name is Victor Anchissi. I key them out when they get saggy. It hasn’t been a problem. I do know what you mean however.

Larry Groff: So, maybe it’s the quality. Regretfully, I’m using cheaper linen. Perhaps if I used better quality, it would be less of a problem?

Langdon Quin: Yeah, maybe. I don’t know. It’s mainly a matter of, seems to me, of using stretchers that you can key out. The problem is once you finish a painting and you’ve got it all keyed out and it looks fine, you put it in a frame then you attach the framing, then you’re stuck with it. If it starts to sag then what do you do?

Larry Groff: You and your wife, Caren Canier—who is also a painter, divide your time between living in Troy, NY and Gubbio in Umbria, Italy. How long have you lived there and what is your place in Italy like? Have you become close to your neighbors? What is it like to live there?

Langdon Quin: It has been a major component of my life and hers. I can’t think of a better way to put it, really. We’ve been here for 33 years,. I taught in the US for 30 plus years, finishing up at the University of New Hampshire in 2010. I always came here in the summertime in those years, but since I retired I’ve been able to come for shorter periods in the winter as well. I do that whenever I can, and I’m here right now for several weeks, which I usually do every February and March. Then I leave, go back to the States, and come back from May through mid-September.

Our place is an old farmhouse that has seen better days, but we keep picking at it and keeping it lovely and pretty much in the vernacular, historic form for this kind of house. It’s sort of a “farmette”. We have gardens, some grapes, some olive trees, and it’s lovely. It’s very nice. Our children have grown up here as well, so they have attachments to it, but probably nothing like ours. We’ve been doing this for a long time. I have a studio here, and I have a studio in New York state, where I live in the US. We’re pretty close to New York City, so we’re there for a couple of days just about every week.

We’re triangulating between these places, and we’re lucky to be able to do that. I spend a lot of time traveling, a lot of money traveling, but at the same time it feels good to move around. I generate a lot of painting ideas here in Italy, and as I said before, I roll up the canvases, and build ideas with those starts I can make, and take them back to the States, work on them there, and often bring them back here. I have sets of stretchers in both places that fit these paintings, so I try to make the transitions as easy physically as I can.

The house in Italy is in a very quiet, rural place. We’ve been here a long time so we have plenty of Italian friends and neighbors that we see a lot of. As with any home, we have our problems with household things, but it’s still nice. We don’t have central heating, which makes it uncomfortable sometimes in the winter and we live with woodstoves and fireplaces going all day. It’s a bit rough, but lovely. I will never complain about it.

Larry Groff: That sounds like such a wonderful life, I’m very jealous! This leads to my next question, which is, does having a deep personal connection to a place, such as in Umbria or Troy, NY is essential to the life or success of your painting? Or is that connections more just a point of departure? That the painting then takes a life of its own, and it becomes more about the formal issues and about the painting itself, rather than the actual thing that you’re painting, or are they inseparable to you. I’m curious for your thoughts about that.

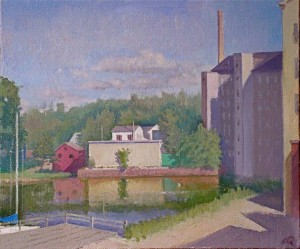

Langdon Quin: In a way, I would like it if my paintings were seamless, that is, a viewer might see that it’s a painting of Italy but that would feel incidental; it wouldn’t look terribly different from a painting of New York State insofar as its feeling. I do paint the landscape in New York State. It’s more dictated by seasonal restraints however. The New York State landscape is quite beautiful, and I value it. The light there is different than it is here in Italy, and different kind of forces on view, and certainly not uninteresting. It’s not like I’m saying,” oh, I can only paint the landscape in Italy”.

It’s about the painting. The initiation of the painting has to do with the place, but the continuity of its development is particular to the painting and not the place. I can do that wherever I am, as long as I have the materials to do it. I do have another kind of feeling about surroundings in the US… at least where I live in New York State,. The culture and history of the relationship of the people to the landscape is very different from the Italians I know about.

I’ll just try to simplify this by saying that one is a sympathetic relationship, and one is an antipathetic relationship, the latter, representing the American side of it. We beat up our world there, and treat it badly and abuse it. And certainly that happens here in Italy as well, but you don’t sense it as much in the countryside because rural people are still so careful about their cultivation and land management, and they seem to prize it more. It’s more part of their patrimony, and lives, and I admire that and respond to that. In America, at least in New York State where we live, it’s a more problematic relationship to the land, which is not uninteresting as an idea in terms of developing something narratively/pictorially, but at the same time it’s kind of a bummer in any social sense.

Larry Groff: I would think Troy would be closer to Italy than any other places. I’ve heard that Troy is one of the few smaller towns like that that have retained its identity. It hasn’t changed quite as much over the years.

Langdon Quin: Our mailing address is Troy, but we live in the country, east of Troy, towards the Massachusetts-Vermont line. We’re out in the landscape and it’s really quite lovely where we live, and we’ve been blessed not to have a lot of rampant development. The last major battle we had locally, was over a Wal-Mart moving in nearby, a decade or so ago. And, as in every other place in America, you can’t stop Wal-Mart. So we tried, but it’s there. But so far, our immediate surroundings haven’t changed too dramatically. However, it is a landscape that’s definitely threatened.

Farming has stalled statewide, and local Hudson Valley farms are shutting down and closing. It’s just a very transitional world there, and you feel it. I don’t sense that as much where we live here in Italy, so that’s among the positive things about being here. I paint the landscape in New York State, but I hold off in the winter, especially in this terribly brutal winter we’ve had this year. I really enjoy being in my studio upstate, but I just don’t get out to paint the landscape much, because it’s just so tough to do that. It’s not very inviting or hospitable.

I’m usually focused more on other forms… I draw a lot from the figure, and paint from the figure, and try to develop more figural ideas when I’m in the States. The ideas are slower to develop, so it’s not a period that I tend to I produce a lot in. Here in the summer months, I can get things rolling more quickly. The days are longer. It’s 8 o’clock in the morning and I can be in the studio if I choose to, and not return ’till 8 at night…

Larry Groff: Who are some of your favorite contemporary living painters?

Langdon Quin: Although I try to look at everybody, I can’t say that I have any particular contemporary heroes right now. There are certainly lots of painters out there whose work I admire. I’m reading a little biography by Phoebe Hoban about Lucian Freud Lucian Freud: Eyes Wide Open (Icons).

But whereas I like Freud’s work. I don’t think he has had any influence on my work, it’s just … He’s a celebrated artist that I respect, and I certainly admire others such as Antonio Lopez Garcia. Their work is impressive to me, and I admire much about their ambitions, and I respect them, but I’m not exactly worshipful. There are lots of people I can mention. Leonard Anderson, Stanley Lewis, Leland Bell, Louisa Matthiasdottir… Another painter who comes to mind, whose lovely show I saw a show about 6 months ago, is E.M. Saniga, whom I don’t know personally.

Larry Groff: He’s a great painter and person. I got to meet him in Civita Castellana, when I was at the JSS in Civita program.

Langdon Quin: Yeah. I saw a show of his, and I thought, this guy is something special. Gillian Pederson Krag is another person that I do know quite well. She’s under many people’s radar, but she’s a terrific painter.

Larry Groff: She’s great, Elana Hagler had an interview with her on Painting Perceptions…

Langdon Quin: She’s wonderful. In fact, she’s my wife Caren’s former teacher, and they’re very good friends, and I am as well. There are plenty of people that I see on Facebook but I don’t know personally, but impress me such as this guy, Emil Robinson’s work, I admire his work (http://emilrobinson.com/home.html)

Larry Groff: Another excellent painter. I also got to meet him a couple of times and had an interview with him.

Langdon Quin: I don’t know him personally. I have to say that I’m pretty negative about aspects of Facebook, but the good thing about it is that it makes you realize that there are lots and lots of people out there who are painting with great intelligence and great sensitivity, that you’re probably not necessarily going to see in Chelsea or anywhere else in New York City. But, it’s gratifying to know that such good painting still flourishes. That feels hopeful; to know that there are people out there that can respond. That’s the way it is when you teach, as well. There are always students that still want to make pictures of people or whatever, and they either do it, or don’t do it once they move on. But they want it at the outset, and need it then, and come to you for that information. You know, life goes on.

Larry Groff: Do you feel optimistic about the future of representational painting, as you’ve grown to love it, the kind of work that you do?

Langdon Quin: No, I wouldn’t say I’m optimistic at all. Actually, I would say I’m a bit cynical about it. For the following reason: I think the saddest thing is that for a lot of people that I know that for a lot wonderfully talented artists who are capable of doing great things, the marketplace and the art world do a lot of damage. They combine to dull the sense of urgency to paint for some very fine painters. If you’re not going to sell the work, you’re not going to show it, then why do it? That’s depressing, and yet most of those people, including myself, just try to keep doing it because that’s what we do. No. I’m not very positive, I’m afraid.

I talk to people about it, and some people say, “Well, all it would take is one or two perceptive art world critics, or dealers, or this or that, and suddenly the whole thing could change positively.” I don’t believe that. I think that the culture is losing its capacity to really embrace painting as a poetic, and essential form. If at all it’s embraced embrace it as something else: celebrity, style, or whatever…

Larry Groff: Fashion.

Langdon Quin: Fashion. Yeah. I don’t like to think about that part of it, so to answer your question, no, I’m not optimistic at all.

Larry Groff: A thought I’ve had for quite some time is the art world’s elevation in importance of conceptual-based art and the fall of painting about visual concerns feels like we’re heading toward some kind of neo-medievalism, in that the painting has become increasingly more about ideas that one contemplates not unlike what people did with the icons during the medieval era. Irony is becoming a new catechism of hipness and beauty no longer has much relevance. Of course visual imagery is still there, but often more to illustrate a concept than to celebrate beauty.

Langdon Quin: Exactly. Even though it’s said that “irony” was over years ago as the expressive vehicle of the art world, it still appears to me that it’s driving the bus !Is distance from any sort of poetic interpretation of things, or an earnest interpretation of things is so huge. And that’s really disturbing. I don’t know when it’s going to change, or if it’s going to change, but it’s certainly seems bleak these days.

It makes me think that, in spite of its power in the marketplace, New York is a terribly provincial place because that’s such a singular attitude that prevails. And that’s just small-minded, and doesn’t make any sense to me. That’s why I say I am not encouraged. I do know that there are places in the Midwest, on the West Coast, everywhere, where people are doing good things and feeling productive and positive about it, so maybe I should cheer up.

Larry Groff: I understand. It’s particularly difficult for people who live away from the bigger art centers. Where I live in San Diego, I think there are a lot of people in the art world here who want to emulate the New York scene. They’re getting at it from maybe 10 years ago or something, but they are even more dismissive of people doing work from observation or other kinds of a sophisticated relationship to the history of painting. They all want to be about the cutting age, but they don’t really think about art history, I think, in a way, and it makes it really difficult for people who are, because you can’t get shown. If you can’t get shown, because they think you’re old fuddy-duddies or something, then you can’t sell your work or get hired as a teacher and it becomes very difficult to make it as a painter.

Langdon Quin: That’s why, at this point in time, some 35 years or whatever it is after speaking with Fairfield Porter that I just cherish that encounter with him—because he seemed to be taking such a stand in opposition to what you describe… Even then he realized what the lay of the land was, and how important it was to embrace an idea about painting that would really transcend trends, time, and shifts in popular culture. I think he was very important in that way. That does make me feel like there is a conversation still going on, however attenuated, and that’s good. This is part of it, you and I talking like this.

Larry Groff: Other people get to read this, and it gives them ideas, so we’re helping to perpetuate this continuum of ideas about making good painting.

There is a poetic quality to so much of your work. I think all really great painting has that, for me it’s the visual poetics that really makes the painting succeed more than anything. Much more than the level of skill in depicting things or the level of realism, or whatever, it’s has to first engage me from the feelings, the mood, the poetics.

What would you suggest for someone, a young person just starting out, wants to do this kind of painting, representational painting, whatever you want to call it, to really appreciate the sense of poetics, the visual poetics. Is there something you would recommend?

Langdon Quin: I don’t think you can really recommend so much. I think It’s nascent or it’s not nascent, meaning that if they want to image something then they have to figure out how to do it, and have to seek out somebody that can teach them how to proceed, or look at something on the walls or in books. The will to image something is pretty hard- wired in many people. That’s what students bring to a beginning painting or drawing class. There’s some fundamental wish to do it, and they don’t know about the art world, or culture, or anything else. They’re just following an intuition that feels important, and that’s what a good teacher will have to build on.

I guess the answer to your question is: if you don’t feel it and you don’t really look around the world and think how beautiful this or that is. Or, “gee, wouldn’t it be nice to image that”—if that’s not there in the first place, there’s no way you’re going to just decide that that’s what you’re going to do. It has to be there in the first place, and I think it is for many people. I think it’s part of our makeup, that we want to image things, and how quickly you get swept up in fashion, or trends, or this or that, is going to dissuade you from doing that, but the people that want to do it are going to find a way to do it, I hope.

It gets harder and harder, but I think that will go on, and remains the refreshing thing about teaching. When I taught in New Hampshire, all these corn and milk-fed young people who were my students came from pretty conventional backgrounds, and weren’t particularly sophisticated, but they wanted to make images., They wanted to make pictures and they wanted to construct figures. Whether or not it continued in their lives in any way later is a different thing, but I think the will to do that is often there. That’s what’s hopeful, I suppose.

Larry Groff: Right. One thought that I had, kind of a grim thought, but I see many things in this society falling apart, and are not really being sustainable. It’s too much to get into now, but it feels like … The one thing that can be real is painting, and it gives you a reason to live. The whole world could be falling apart, but you’ve got a great painting in front of you that you’re working on, it’s sort of, like, so what? I’ve got this painting, and it gives you a reason to keep going. It gives hope and it gives a reason to live.

Langdon Quin: Painting is a political act, and if you paint that harbor, Larry, and you say, ‘I saw this and it looked like this, and it felt like this,’ and, again, paraphrasing Porter, ‘You particularize an experience and you make it an individual stance in a form that can be shared,’ it’s essentially a political act. You are saying to other people, “I want you to see this the way I see it,” and when you do that, it may or may not resonate with a viewer, but it means something to try. Again, to reference Porter, because I think that’s what he was saying, it’s that ‘this is what you have to do. You have to communicate the particularities of things that life in its visual realm presents’

I got to know Langdon in the later 1970’s just after he finished at Yale, as he was an undergrad at Washington & Lee University just north of us at Hollins University in Roanoke, VA.

I have followed his work over the years and have admired his subtle color and clearly constructed compositions.

His quoting of Fairfield Porter is important for me too as it resonates with a way of seeing and making ones work. To respond to the world around us, and to find a way to invest it with our feelings for the place and time. Porter also saw the necessity of making the paint and the mark something that was itself responsive to expression.

I heard in Langdon’s comments the sincerity of his feeling for making painting an authentic personal expression. His concern for luminosity in color as light and the space that is to be felt and constructed by color came through in his remarks as it does in his work.

Having a homes in Umbria and NY state, and having a long and distinguished career as a teacher has provided him with the life which feeds his paintings. I know too as a teacher that the best we can do is to guide our students to find their own path and follow their instincts but we need to give them the visual resources to make a coherent form. Langdon has done that for a whole generation.

Your interview has been illuminating and is a clear reflection of the man and the painter. Thanks for doing this and sharing it now too.

Bill White

Professor Emeritus at Hollins University

Thank you for sharing this thoughtful interview. I really enjoyed this– I could almost hear Langdon’s voice speaking as I ready this, shooting me back to when I was a student in his classroom at UNH 15 or so years ago. It’s a real pleasure to see his current work, and have the opportunity to learn from him once again.

Thanks, great interview. Love to hear about processes and ideas.

This is a wonderful interview with Langdon, who was a fellow student with me at Gabriel Laderman’s summer class at Tanglewood, Massachusetts in the early 70s. His future wife was also there at the time. Happy memories. Langdon’s work has grown not only in color and mastery but (for lack of better word) in MAGIC. The paintings are radiant, mysterious, and full of life!