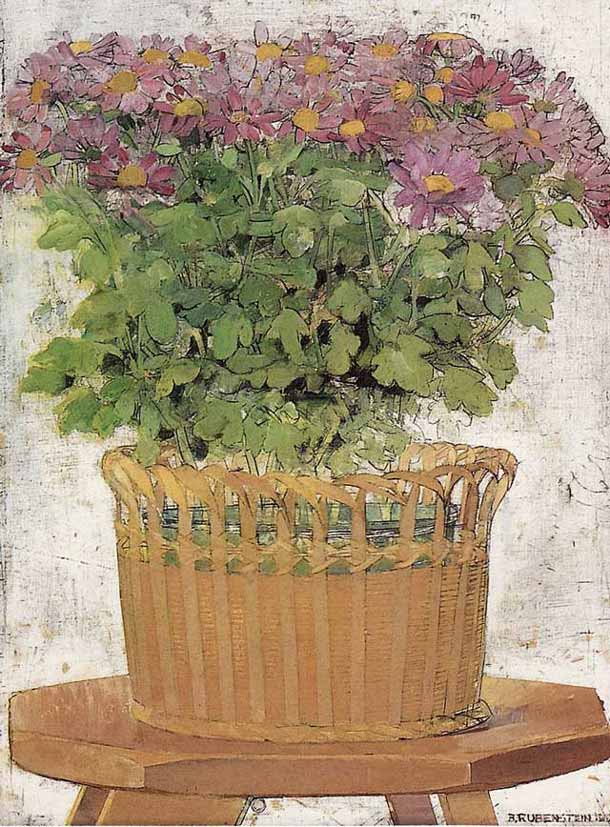

I recently received a wonderful essay from a former student of Barney Rubenstein who is generous and kind enough to share some of his experience studying with Barnet Rubenstein. Barney (as he was known) was an important figurative painter in Boston, painting primarily still-life, often painting take-out food containers, cardboard boxes, jars of cookies, and arrangements of fruits and flowers. Barney taught at the Boston Museum School for 30 years. He showed at Boston’s Alpha Gallery and had a show at the Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 1979 as well as a major retrospective at the Rose Art Museum in 1997 showing four decades of work.

Regretfully, I could only find limited amount of his work online, as I find more images I will put them up here at some later date. I would love to include any information or images that anyone might wish to share. There is an excellent obituary and tribute written by Carl Belz at his Left Bank Art Blog. Carl Belz is Director Emeritus of the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University. Carl Belz stated in this blog post that:

Throughout his life—in his art, in his teaching, and in the stories he memorably told—Barney communicated a deep respect for art’s recent and distant past. In this he followed the model he learned as a student at the Museum School more than a half century ago, and he in turn gifted it to the generations of aspiring artists who studied with him, just as he gifted it to countless colleagues and friends, which was always with boundless generosity. He extended the same respect to the humble objects he painted—the fruits and flowers, the cookies and jars and boxes—patiently articulating each of them with nature’s life-giving light and attendant color. We know the pictures came about through painstaking effort and were hard to part with, but we don’t feel that effort when looking at them. We feel instead their joy and wonder, how they justify themselves by merely existing, and we in turn feel as though their maker was grateful simply for the opportunity to bring them into being. Such is the gift of art when it is practiced at its highest level, which is the way Barney practiced and gifted it, and a supreme gift it remains.

REMEMBERING BARNEY RUBENSTEIN by Richard Dean

Before saying anything about Barney I should first say that I’m very aware that (a) memory is fallible, (b) it was a long time ago, and (c) plenty of other people knew Barney better and for longer than I did. Maybe some of them, reading this, will come forward with their own memories and reflections. I hope so.

The Boston Museum School in the mid- 70s was a pretty rough and ready, free and easy kind of place. Once they got the exorbitant $3000 or so that it cost to go there in those days you were pretty much on your own. Students came and went, no one kept a register of attendance, staff brought booze into tutorials and basically you did what you felt like doing, which in my case was goofing off, mostly.

I wasn’t very happy at the Museum School but I stayed for two years and the main reason I stayed was so I could hang around Barney Rubenstein.

Barney (nobody ever called him “Barnet”) was the benign presence around which the noise and life of the Museum School swirled. You might not know who the Principal or the Dean or whatever he was called was, but everyone knew Barney. With his moustache drooping over his mouth, to which a cigarette was permanently attached, his glasses hanging from a chain around his neck, with his Staff ID worn upside down and his, um, deeply relaxed dress sense, you couldn’t miss him. He spoke in a low, slow, drawling voice and you listened because he had been everywhere, had met everyone and had seen everything, apparently. He’d been to France! He lived at the Chelsea Hotel! He knew famous artists! Wow, this guy is the real deal, we thought, and we were right.

As a teacher Barney had no particular agenda; he showed up, he talked, you listened and you learned. He dropped hints, made suggestions, he negotiated with you. “Why do you put that black line around everything?” he asked me once. Because it makes the picture look modern, like a Léger, I said. “Well, it doesn’t. It’s kind of… boring. Maybe, um, you shouldn’t do that”; which from Barney meant that you should absolutely, definitely, positively cease and desist at once from what you were doing and never, ever, return to that particular piece of folly. I dropped that black line like the bad habit it was.

Barney wasn’t one to grab the brush out of your hands and show you “how” to do it. We understood that Barney knew all about how to do it and the various ways one might do it and he wanted us to learn for ourselves how it might be done, not to just obey orders from some authority figure. As a serious artist, he treated his students as colleagues to be consulted, not as inferiors awaiting his instruction.

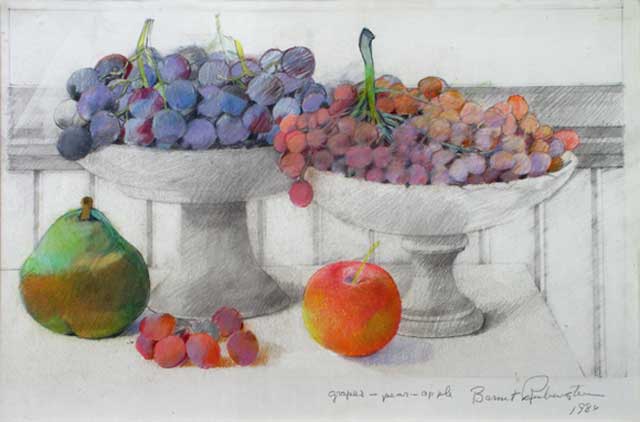

Grapes, Pear, Apple, 1984, pencil and colored pencil on paper, 10 x 15

Sunflowers and a Rose, late 1990’s, pencil and colored pencil on paper, private collection

He was the least egoistic of teachers; he wanted to hear about your ideas and intentions a lot more than he wanted you to hear about his. We were mostly young kids, fresh out of high school. Barney was the first grown up who ever took us seriously and was interested in what we were saying and that means a lot to a young person.

In art, Barney had very broad taste. Personally he liked Peto and Harnett and Balthus but he also liked Rauschenberg and Guston and Alice Neel and Richard Estes and Robert Smithson. He told me about how good Sylvia Mangold, who was just starting out then, was but he told me about Robert Mangold too.

He made us laugh. “What were you doing, living for so long in Aix-en-Provence like Cézanne?” someone asked. “Looking for his paint rags” Barney said. One night Gabriel Laderman arrived at some Boston Museum event in this flaming red shirt. “So, are you a follower of Garibaldi now?” asked Barney. I didn’t quite get the reference but I knew it was funny.

Interior / Exterior, oil on canvas, 1981-87

For his students Barney became a model for what a real artist should be. Real artists should work hard, should be open to ideas and experience, should ask questions and look for answers. Real artists didn’t take anything too seriously except for their work, which was absolutely serious and real artists didn’t pay any attention to fashion or fame. Real artists looked at everything and knew the whole history of art and kept on learning, always. Art was slow and real artists took their time.

In those days the Museum School and the Boston MFA were boiling hot beds of Greenbergian formalism. According to the Contemporary Art Department of the MFA the only people who mattered were Tony Caro and Ken Noland and Jules Olitski and any painting that wasn’t Color Field didn’t matter, especially if it was representational. Barney paid no attention to any of that stuff, he built an 8 foot square wooden frame and divided it with a grid of string and set it up on the studio floor between his still life set up and his painting table and got to work like it was 1500 and he was Albrecht Durer.

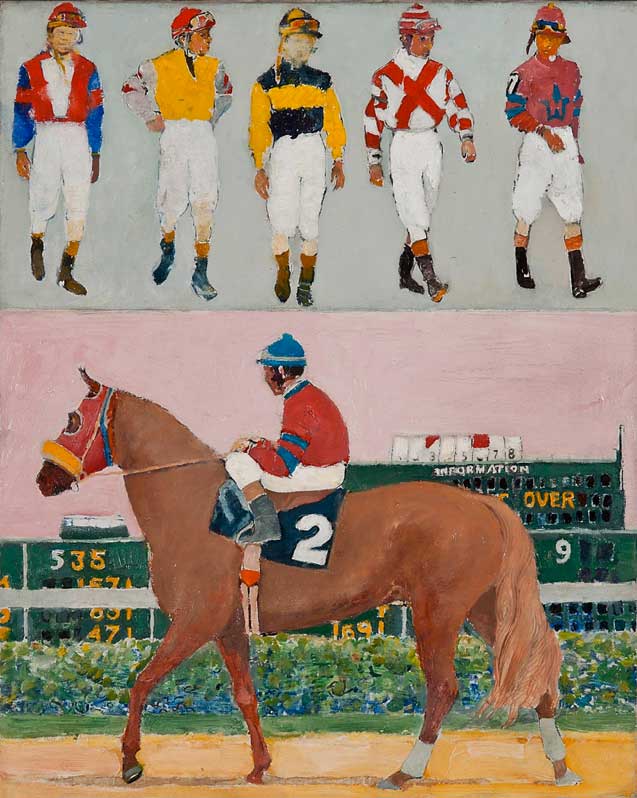

Once Barney painted ocean liners and race horses but latterly he did still lives and interiors. Simple subjects; jars full of biscuits, pieces of fruit, the view from his window, a pile of cardboard oyster pails and he painted them really, really slowly. Fruit would rot and plants would wither before Barney had even got close to finishing his paintings of them.

There’s no painterly rhetoric in Barney’s work, no slapped on paint or busy brushwork or compositionally convenient drips. Everything is restrained and steady, everything has been thought about. He might have studied with Kokoschka but there’s no angst or hot emotion in what Barney does, it’s all much more subtle, considered and cumulative. Everything is there for a reason. His pictures took a long time to make and they can take a lot of looking. That the longer you look, the more you see is a cliché but in Barney’s case it’s absolutely the truth.

Barney drove dealers and collectors nuts because he didn’t work to make them happy and that, along with his more or less total indifference to furthering his “career”, is probably why he wasn’t better known in his lifetime. He could have been but he didn’t care about that stuff, not really. He cared about painting and smoking and talking, especially about painting. Always painting.

Richard Dean attended the Museum School from 73-75, then moved to New York and went to the Art Students League before moving to the UK where he’s lived for the past 20 years, teaching at the art school in Canterbury as well as working at the Canterbury College.

i am grateful to my colleague, Richard Dean, for making me aware of such an interesting figure and one with a kindred artisitic spirit- one that our students can be inspred by now.

Thank you, Richard Dean! Barney was all that – and more. A most amazing man. I was a Museum School student from 75-79. Barney was the reason I stayed long enough to actually get a diploma. Just something about him. You knew he held the secret. Kind of a Buddha type. He was in his own world, and his world was the right world. You had to really listen to receive your enlightenment. He was so easy going, sometimes you just didn’t think he was taking it all in, but he was. I will never forget a Review Board I had that Barney was on. The other faculty member assigned to my board intensely disliked Barney. He was a very pretentious man who could never stop commenting on how important he had been. Barney was seriously late. The other faculty member refused to start my review without Barney’s presence. He was running out of insults when he realized that half of my board time had past. He was thrilled. He informed me that I could file a Formal Complaint against Barney. He thought it was time that Barney be reprimanded for his haphazardness. I told him I was willing to wait. That even a 5 minute board with Barney was worth more than a two hour board with anyone else. Barney showed up with a 1/2 hour to spare. It took him a while to focus. My board, at that moment, was complete chaos. I waited. Barney spoke. With a two sentence review, Barney opened up my world. These were the exact two sentences I needed to hear. He forever changed the way I looked at art and the way I would work. I adored Barney. It is so appropriate that I saw this on Thanksgiving Day. I am truly grateful that I had a chance to know Barney Rubenstein.

I was a student of Barney Rubenstein. I had the privilege, along with my classmates, to see work in progress in his studio. I have a small sketch of his that he let me keep. It’s not signed, but I would like to share it. The drawing was part of his teaching.

Great story! I went to the Museum School in the mid to late 80’s. I studied with him too, but he wasn’t on any of my review boards. A lot of his critiques were one to two word sentences.

Dear Sharon

Thanks so much for sharing your excellent Barney story, you made my day. Have a happy thanksgiving!

Thank you Mr. Dean for writing. I bought a book of contemporary still life painters at a used book store years ago and fell in love with Mr. Rubenstein’s work. His boxes and cookie jar paintings in particular. He joins all the other wonderful modern realist painters, like William Coldstream and Euan Uglow, helping us to see the world through contemplative eyes. His work gradually slows us down, and as we slip out of time into the present moment it rewards focused viewing with the kind of uncanny experience of reality that is only possible with lovingly painted depiction. His delicate drawing, resonant color composition, subtle light and atmospheric pictorial space combines with his slow paint handling and choices of subject matter to make work that is wholly postmodern while embracing modern painting. His work causes us to be quiet, like a Morandi. It works on us at a level much deeper than language. Mr. Rubenstein’s art is purely visual, and a delight.

I think I may own a Barnet Rubenstein painting and would like to send you a photo of it. It belonged to my husband who has recently passed away. It was placed under our insurance plan but the name is spelled Barnnet Rubenstein, perhaps a typo. Perhaps you can help me identify it?????

Ms. Judy Karr, I’d be happy to see your photo of what is likely your Barney Rubenstein painting. Of course, my (or any other viewer) are likely just going to be guesswork. Obviously, if you’re looking for something more definitive you should contact his estate/gallery or other art appraisal expert.

Barney was more than a brilliant teacher. We became friends during the brief time I was at SMFA. I learned more about ” seeing” from Barney than anyone else. Barney was a superb painter but more, he was a great guy.

Thank you so much for your lovely tribute to Barney. I was quite sad when I heard he had died. I learned so much from Barney. I loved his stories. I loved the way some students would walk away bewildered when they asked him a straight forward question, some painting technicality, & he would proceed with a quote from Yogi Berra. I can still here his voice.

Hello– have really enjoyed reading this. I was a student of Scott Brodie who was, in turn, a student of BR– I’m wondering if anyone has further details of BR’s studies. Kokoshka is mentioned regularly- Does anyone know where and when? Many thanks. Thomas Lail.

Dear Scott

Kokoschka had a show at the ICA in Boston in 1946. This item relates to that time. https://www.skinnerinc.com/auctions/2750B/lots/591

OK did some teaching locally at that time and I think that’s when Barney (and Henry Schwartz too) met him. Kokoschka had his famous School of Seeing in Salzburg during the 50s but I don’t know if anyone from Boston was ever involved with that.

Jack Kramer , Reed Kay ( both MSFA ALUMNI BMSFA) were invited to teach Drawing in Salsberg byOK. At a later date.Henry Schwartz studied in under OK in Austria. Reed Kay is the only living one of the three. I wish I had. I am one of the few painters left of that period. Barny was a student trying for a travelling scholarship and I a year bekhind Barney. I never knew him to speak to then or for that matter when we taught in the painting dept on different daystaught at the school on the same days as he then lived in NYCITY in the 60’s. One day Barney was in the parking lot lookig as if lost and i asked him if he needed a.lift.He was quiet but knew me by sight. He referred wistfully looking to my gardening materials I purchased earlier in the day. Mid drive he randomly picked spot to gat off.He looked lonely and that was the last day ofthe school year. I had just returned from living in Scotland for years and saw his BMFA show and I was surprised how the work changed. met Joe Hodgson who said a letter from me about his work would be a boost he needed.and I wrote praising his new work but he probably didnt kow me by name.Not much of a story but it explains the ” man” 1978 perhaps. He was seeking to renew old connections from his stdent days adrift..It touched me.

In the 1950’s Russel Smith, the head of Museum School at the time, invited Oskar Kokoschka and Pablo Picasso to head the Museum School painting department. There was no word back from Picasso; but this invitation may have led to Kokoschka’s teaching at a Museum School Summer Session at Tanglewood in the Berkshires in the 1950’s. Quite a few Museum School students took part, including Gene Ward and Joe Hodgson, who later became museum School administrators. I’ve wondered if this summer school teaching experience of Kokoshka’s may have led, in some measure, to his establishing his own summer School of Seeing in Salzburg. (I did the Summer session there in 1965; but unfortunately Kokoschka had retired a year or two before I enrolled. Still a great experience.) The influence of Kokoscka’s teaching, particularly on Henry Schwartz, who went on to be OK’s teaching assistant in Salzburg, can be seen carried on in the amazing expressionist painting of Henry’s student Gerry Bergstein. Museum School remained an academic/drawing based school well into the 20th century—later than many. Possibly due to the excellence of traditional “Boston School” teachers, such as Tarbell and Paxton. When Russell Smith became head of the school (around 1940?), he may have seen his task to be that of bringing the school into the modern era. German expressionism may have enabled him to retain the school’s realist tradition, now updated in a way, through the German influence.

I bought a beautiful color print by B.R. of a vase of blue irises, baskets and bowls of fruit and a rose from the estate sale of Bernard Chaet in New Haven. It is roughly 25×32, marked as AP artists’ s proof No 1, signed and dated 1983 by him. I would like to sell it. If any one know a good place to reach out to please let me know. Thank you…

Hello afet

I never knew Barney had made any prints. Have you got an image of this piece you could share?

Hello… I will send the pictures via email. Probably a Litho. Thank you,

That’ll be interesting to see. Thanks.

I would be interested in buying it please email me natemeyer@hotmail.com

Hello Nate,

Thank you very much for your interest in buying this print. One of my clients already bought it.

OK He was my still life teacher I would love something by him.

Hello Nate,

If I ever get my hands on another one or my client considers selling it, I will certainly give you the first choice to acquire it… I do have other works of art by other academics like Bernard Chaet, and Jesse Dominguez in case they were also your teachers. A

I have a poster of “Fritz’s Doors” that is very pretty. [1977-1979, Oil on Canvas]

My parents bought it at a Museum School fundraiser. I am wondering if somebody might like to buy it from me. Thank you! (I have 2 children in college and I am selling various items on eBay)

I came across a lithograph of a mime / marionette that has b. rubenstein signature on it. Would love for someone familiar with his work to take a look and let me know if they think it was from Barnet.

Please email me at trekas@onepunch.net

Thanks!

Terry

Hi Thomas, Oscar Kokoschka taught in the Museum School’s summer session held in the Berkshires in 1948—49.

I recently began a blog, and posted on October 3, 2020 about an important lesson learned during my art journey. This post was about Barney Rubenstein, my teacher at The School of The Museum of Fine Arts Boston and a valuable lesson he taught me back in the mid 70’s. I still hear his voice and remember clearly how it felt… even though I didn’t get to study with him for long, only a year, he is forever etched in my life. Thank you for your article, it really described him well, a wonderful time in the 70″s! Having Barney in my life, ever so briefly was such an honor! https://www.patthompsonart.com/blog/161229/the-derailed-artist-use-the-best-materials

I studied with Barney in 1970 and in my graduate year at SMFA he encouraged me to do graduate work and compete for a traveling fellowship. With his encouragement I succeeded and awarded with a fellowship that changed my life in many ways. Barney taught me many things, but most of all he taught me that it was alright to not be a painter and explore other things. After a brief stint as a painter I did in fact do that and in exploring another media found a true calling and was richly rewarded. He was a truly great human being.

I thank Richard Dean and other Barney students for bringong back wonderfulmēmo ries of him .I studied with Barney in the mid 80s . I would dearly like to one one of Barney’s works .

Sharon, I know this is very late, but I was just doing some research on Barney and I think you were the one that asked on another site if anyone knew about his background, because you have relatives with the same name.. I’m his niece and know a little. Let me know if you want to communicate.

Louise

I had Barney as my painting teacher in the mid 80s at the Museum School. He would just come around every now and then to where I was working in the studio, Gerry Bergstein said, “Barney always says the right thing, it might take a year, but it’s worth waiting.” I took that advice. He was funny and enjoyable. Along with another woman in that studio, he would counsel us to paint what was beside our beds on our night tables. He was sure we kept lipstick and powder compacts on our night tables. We assured him we did not. After a long time, Barney suggested I look at Luisa Matthiasdottir and Rafael Ferrera. It was just right. Barney spent endless time on his paintings. I can remember that painting Fritz‘s doors, he waited for the light to be in the right place each day before proceeding, and the same with the cookie jars, which I really loved.