Review by Thaddeus Radell

Anthony Fisher paints as if his life depends on it. Trite as that may sound, there are few exhibitions of contemporary painters that give such evidence of the will to paint. In his current show at Galerie Mourlot, Fisher’s work explodes into view.

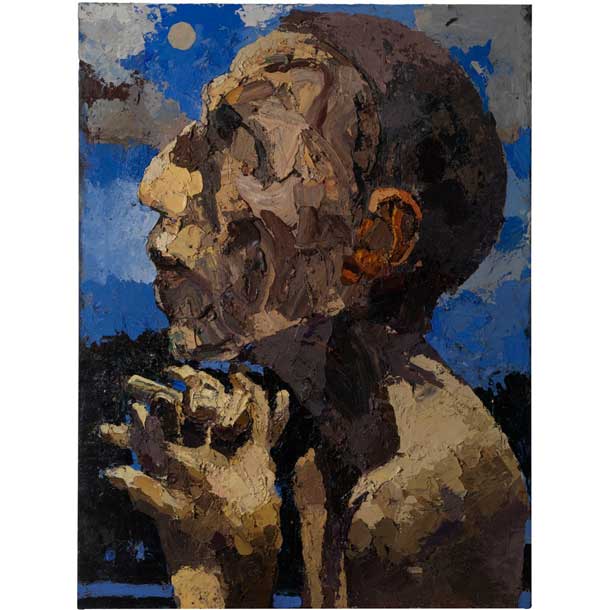

Immediately upon entering the intimate, almost delicate space of the gallery, one is confronted by three imposing portraits that work so well together, that so resolutely support each other, they seem assuredly to have been conceived as a triptych. All three works are large monumental heads of the same model. Furthering the effect of a triptych, the central panel consists of a frontal pose and the two side panels offer opposing profiles. Again, all three works have a similar, if not exact, pose. The artist did not, however, conceive of them as a triptych; the pictures assumed this exciting and spirited order only upon the gallery installation. Fisher works many studies, both drawing and painting, and these portraits are culled from the broad base of this effort. The overall energy that the three pieces hurl at the viewer would almost be excessive if it were not for the sitter’s pose itself. Eyes shut, head slightly tilted, hands joined with interlaced fingers, the pose is peaceful, solemn and devout. The ambitious scale of the heads is powerfully answered by the gnarled invention of the hands, which indeed may fuse into one knot of tense yet fluid paint, as In Night Supplicant. Here the hands become an arthritic stump catapulting small staccato notes of blue up and under the chin, miraculously supporting the cantilever of the head. The image of a man praying of course brings to mind the early drawings of Van Gogh of men in prayer. The tactility born of Fisher’s interaction with the paint itself is not without echoes of Van Gogh, and in the broader context of an artist extending feeling and meaning into paint, the parallel continues.

The religious and spiritual overtone of pose is all the more pronounced in its contrast with the massive scale of the head and hands that have been slashed, pasted and seemingly dragged and bitten from paint into life.

Fisher’s palette is subdued and limited to rich earth tones, blacks and a few robust blues. Applied with alacrity, the planes of color slam into and onto each other and indeed risk becoming somewhat visually claustrophobic, at times almost suffocating the form. However, these are intelligent paintings and Fisher is a master of his craft. The adroit placement of subtle harmonies of blue alleviates the accumulation of stacked planes of umbers. In Night Supplicant, blues engage in full-throated tones that silhouette and forcibly prompt the diversity of the earthy head tones into monumentality. By contrast, in Penitent, the blues are reduced to a minimum, keeping the painting alive and breathing through an almost maddeningly exquisite placement: a ragged sliver along the jaw, a droplet above the ear, a collar-bone/river defining the landscape behind, fantastic opposing braces of cool relief sucking the arms into the format. This is solid, expressive, fine-tuned painting.

If in a truly visceral sense these paintings engage us, their insistence on a spiritual, or, in the artist’s words, metaphysical sense, is what separates them and elevates them above the rabble of contemporary efforts in painting. “My goal is to elicit an emanation from my ‘sitter’ of the interior life; to allude to the unconscious, the realm of feeling behind our actions.” Fisher is an intense man, expressing himself both in conversation and through his art in a forthright, unabashedly emotive manner. His devotion to the interior life, his overt assertion that what matters is not only the physical representation of form but its meaning, is critical to understanding his art and its relevance. Fisher brings to mind Jacques Maritain’s contention that “an artist is a man before being an artist.” And this, I believe, is the central core and power of this work. By committing himself to meaning, as opposed to limiting himself to the physicality and strictly formal aspects of pictorial representation, Fisher raises the bar. In no way dispossessing himself of the sanctity of painting, with all its inherent visual principles, he reveals himself as a deeply introspective man. A man who paints. And paints well.

This conscious pursuit of feeling and meaning is even more intriguing for its dependence upon observation. Upon first viewing, these works could easily be interpreted as completely synthetic constructions conceived entirely by memory, imagination or some sort of narrative conception. Though Fisher does indeed use memory, he is essentially an artist devoted to direct observation, whether that entails following the decomposition of slabs of meat on a table, working from a live model or relentlessly studying a life-cast he had made of his favorite model and set up in his studio. That observation informs his work is witnessed by the solid drawing and the sculptural establishment of the planes describing the head or hands. The soundness of these planes is only surpassed by their intuitive diversity of shape and tone. The presence of a sitter is clear, yet elevated to a heightened poignancy through the insistence on working through the physical to a more profound representation of the psyche.

The exhibition continues with compelling works on paper, both minor studies and large, fully developed drawings that reaffirm the artist’s consumptive pursuit of his theme. The motif of head and entwined hands never reads as repetitive or contrived throughout the exhibition. Each piece is a unique inquiry, a basis for new pictorial revelation. The effect of such a gathering of similarly conceived compositions expounding piety, or at the very least, a splendid spirituality, is so moving that it transforms the Galerie Mourlot into a sort of chapel, and one is almost prompted into a state of meditation. The most intriguing of these works on paper are, like the oils, large and imposing. Portrait with Hands Clasped is underscored by a poetic sensitivity of line. Drawn in an Old Master sanguine tone, the line gathers weight and suppleness through its interaction with a scumbled white under-painting that the artist engages to erase and rework his drawing. Of special interest is The Alchemist. The only major work exhibited that adds the motif of a stack of books beneath the praying figure, the configuration becomes naturally intriguing and that new potentiality of meaning is encouraged by the title. The alchemy of transforming matter into spirit is Fisher’s strength and his exhibition at Galerie Mourlot a welcome sanctuary for those of us praying to the same solemn gods of Painting and Drawing.

Anthony Fisher’s exhibition, Recent Work, continues at Galerie Mourlot, 8 79th St, until May 14th.

Review by Thaddeus Radell

perhaps you mean ‘trite,’ not ‘contrite’ in the first line

Thanks Kathleen for spotting that mistake and letting us know.

These are powerful, introspective pieces that push and pull visual space, mind and spirit.

An article that I will read and re-read!! It captures the spirit of the art and the artist- when I first saw the work I immediately felt of them as Icons (Contemporary Icons to be seen with reverence, technically perfect ) – alive with the energy of the sitter , the artist and the paint itself!!

great article…. seeing in person is truly moving…