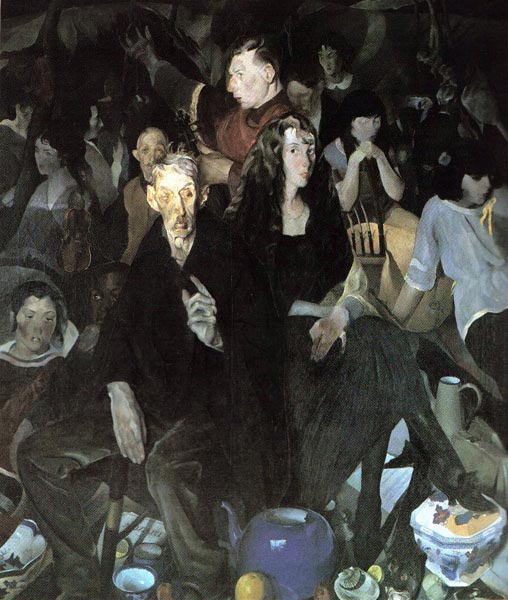

Edwin Dickinson, (American, 1891-1978)

An Anniversary, 1920-21

Oil on canvas

Collection of Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

framed: 81 x 69 x 3 3/4 inches

First Exhibition: A Lineage of American Perceptual Painters, January 15 – March 1, 2015

|

ARTISTS

|

||

|

|

|

Exhibition website

St John’s College

The Mitchell Gallery

Annapolis, MD

Exhibition lecture by curator Matt Klos will be given on February 17th at 5:30pm and there will be a panel discussion with some of the artists on February 22nd at 3pm. All are welcome

Opening Reception on January 25th from 3:30-5pm

This exhibition is curated by Matt Klos, Associate Professor, Anne Arundel Community College, with assistance from Lucinda Edinberg.

Matt Klos is a member of the Perceptual Painters group and has been interviewed on Painting Perceptions.

A Lineage of American Perceptual Painters

by Matt Klos, Curator (in an essay for the exhibition brochure)

Edwin Dickinson (1891–1978) once said, “The more I’m influenced, the more original I get.” Painters often learn first by looking at other painters; however, a perceptual approach to painting is not based purely on rote observation but rather the subjectivity and interpretation of sight. Painters also learn through the passing down of knowledge from one artist to another. Many perceptual painters of the early 20th century and later worked closely together, either as student-and-teacher or as colleagues, influencing each other’s work and artistic process. The Mitchell Gallery exhibition “A Lineage of American Perceptual Painters” focuses on the relationship between artists; in particular, Charles Hawthorne (1872–1930) and his student Edwin Dickinson, and the line of painters that were influenced by Dickinson.

This exhibition includes works that reveal concise connections between the artists involved as well as works that may not directly relate. For example, Dickinson’s and Welsh painter Gwen John’s work both hold a special regard for touch. In John’s paintings, fragmented touches were scumbled or dabbed, building to a gauzy wholeness, whereas in Dickinson’s paintings, vigorous globular daubs, slashes, and slabs were often scraped away and fused at the edges to create a misty wholeness. And each artist’s influence is filtered down into works such as Neil Riley’s Late Winter Aspens. The painting is divided between a deep warm gray mixture and a light blue swath of snow. Many areas of the surface reveal the tone of the underlying painting board or are covered with only a thin veneer of paint. Other areas of the surface are covered thickly with fat pads of paint which lay, unmodulated, on the surface accentuating a flicker of light on a snow mound or a patch of sky unobscured by an aspen’s branches. Broken linear slashes are dragged into the wet paint suggesting both fallen limbs and snow covered ground between trunks. John’s and Dickinson’s disparate senses of touch converge here.

John and Dickinson share a direct engagement of working from life, then diverge; in particular, in terms of different practices, techniques, and responses to what they are observing. As each artist goes through their own way of “figuring it out,” the resultant artwork becomes more than a simple or mannered representation. Each of these artists contends with empirical representation, and through the process of careful looking they build a unique sensation that goes beyond the veneer of representation. These paintings are accumulated moments. Some were made in an afternoon and others were made over the course of many months or years. When engaging with these paintings one can sense both brevity and timelessness. Mark Karnes’s Dining Room into Living Room presents a totality

of the interior scene, and in our revelry we can imagine the undulation of light that occurs in such a room on overcast days.

Gideon Bok (American, b. 1966), The King of Nails (detail), 2006-2010, Oil on Linen, 70” x 79” (Courtesy of the Artist)

The painting is complete and whole yet not static or crystalized. Dickinson’s complex studio constructions combine his love of the Venetian Renaissance with modern modes of painting. An Anniversary, a swirling cacophony of still life objects, figures, and furrowed spaces, reveals both a fidelity to painting naturalistically and a romantic dreamlike quality. Like Dickinson’s other epics, this visionary painting combines clearly definable objects and figures in mysterious environments that contain aspects of both interior and exterior. In spite of the naturalism in An Anniversary, and the space that is created in the work, there are elements of flatness, too. The King of Nails by Gideon Bok. In the painting, Bok uses multiple viewpoints and combines them by interlocking each beam of this sprawling frenetic interior. The effect is both rhythmic and closely observed; lending a sense of movement and transience that is amplified by thinly painted apparitions in the space.

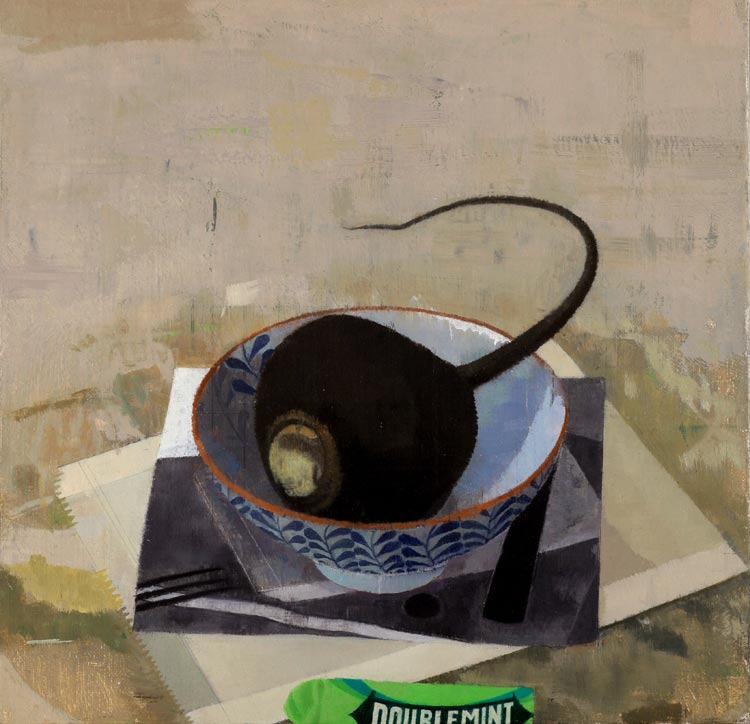

Susan Jane Walp (American, b. 1948)

Doublemint, 2010

Oil on linen

Courtesy of Tibor De Nagy Gallery

8 1/2 x 8 3/4″

In contrast to the expansiveness of Downes and Bok is the pensive inward pull of the portrait Rubin Eshkanian by Lennart Anderson. The geometry of the surface is revealed in punctuating darks and blooms of color: blues, orange, pink, and violet, hedged in by neutral grays. Susan Jane Walp’s Doublemint similarly turns in on itself. The small scale of her work does not diminish, but rather it accentuates the painting’s density. Upon first looks the pattern of the leaves on the bowl, the type on the gum package, and the image of fork tines exert themselves. A slower read, though, shows that these patterns are echoed in other subtle patterns: the deckled edge of the flattened bag and even the organic patterning of the surface these carefully arranged objects are sitting upon. The viewer is entranced and drawn in.

When looking at Edwin Dickinson’s work, it is striking that he painted with such range and that his creativity seems wholly nonjudgmental. He painted with the joy of large color spots and the severity of tightly observed achromatic passages. Sometimes he painted quickly and sometimes slowly over the course of years. Some work was significantly abstract and some highly realistic. Some paintings were dreamlike and poetic while others were mathematical and geometric. When taken on the whole, Dickinson was a painter that seemed more interested in the connections of things (objects, people, landscapes, history, and stories) than in the divisions between them. His art was that of wholeness. Dickinson left a broad creative legacy that has been proved a fertile resource to many painters throughout the 20th century as seen in “A Lineage of American Perceptual Painters.”

Second Exhibition: “Subject and Subjectivity,” curated by Matthew Ballou

This exhibition will be held at Anne Arundel Community College in the Cade Gallery. The exhibition runs from January 26th through February 26th with a curator’s/artist’s talk in the gallery on January 28th at 11am, an artist’s talk by Matthew Ballou at 1pm in Cade 326, and an opening reception that evening from 6-8pm.

Perceptual painters do, in some sense, have a mannered approach to their work. The mannerism is related to their sensing and becoming increasingly aware of the visual character of sensing light, form, color, focus, and space; these are the core subject matter of the perceptual painter. An area of light may become as dense and impenetrable as stone. A solid form may be seen as diaphanous as atmospheric space. These are but two examples of the syncopated intersubjectivity of our senses.

The focus of this exhibition is object studies – perhaps singular, perhaps in tableau – that are aimed not at the slavish presentation of the appearance of objects but rather find their true subject in the scanning, flashing, point-to-point-yet-all-over arrangement of visual and material phenomena. These works move beyond the notational or the schematic to embrace an experiential subjectivity. -Matthew Ballou

|

ARTISTS

|

|

I cant wait to see this exhibition, I love the quote at the top about influence, I think that’s true in all our lives..