I was fortunate to meet Connie Hayes last summer in Civita Castellana, Italy and was curious to find out more about her terrific new body of work and want to thank her for her time and for sharing thoughts and images of her recent Italian paintings.

Connie Hayes lives in Rockland, Maine and shows with the Dowling Walsh Gallery in Rockland, Maine. She received her M.F.A. from Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia, and Rome; her B.F.A. from the Maine College of Art in Portland. She received a fellowship to attend the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1989. Born in Gardiner, Maine she taught at the Maine College of Art for 10 years, also participating in arts administration there for 15 years, including serving as the interim Dean of Faculty. In 2003 she was awarded an honorary doctorate in fine arts from the Maine College of Art. From 1992-1998 she lived in New York City. Since 1990 she has been painting on location through her Borrowed Views project and working in her Rockland Studio.

Larry Groff: You’ve painted in Civita Castellana, Italy the past two summers? What brought you to this place and to this new body of work?

Connie Hayes: I love Italy, right from the start in 1980 when I first lived with eight other painters in Rome for a year of graduate school. Art history classes were held in churches and museums, studying works by artists like Giotto, Piero Della Francesca, Titian, Raphael, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Caravaggio and Fra Angelico. To put my eyes inches away from where these painters’ hands worked thrilled me. It still does. In 2014 and 2015 I was invited to return to Italy to teach at the JSS in Civita School, a serious painting program in the Italian countryside. I was again ready to “borrow views”—this time, sharing my process of translating views. For this excitement, Italy fits my passions well.

LG: What was your experience like in Civita Castellana?

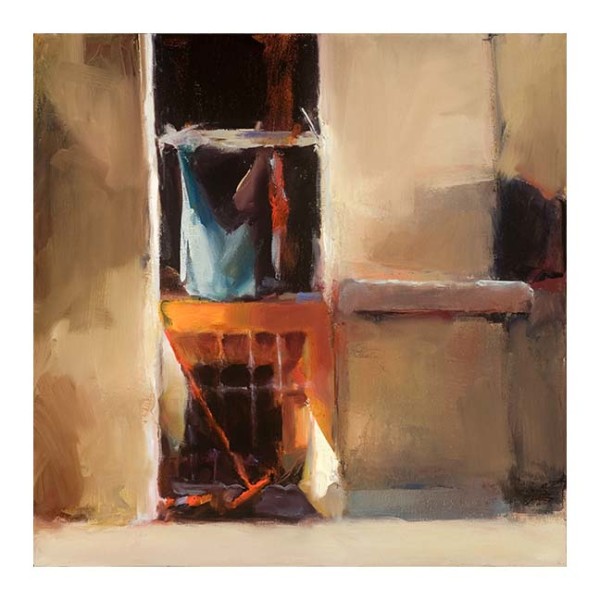

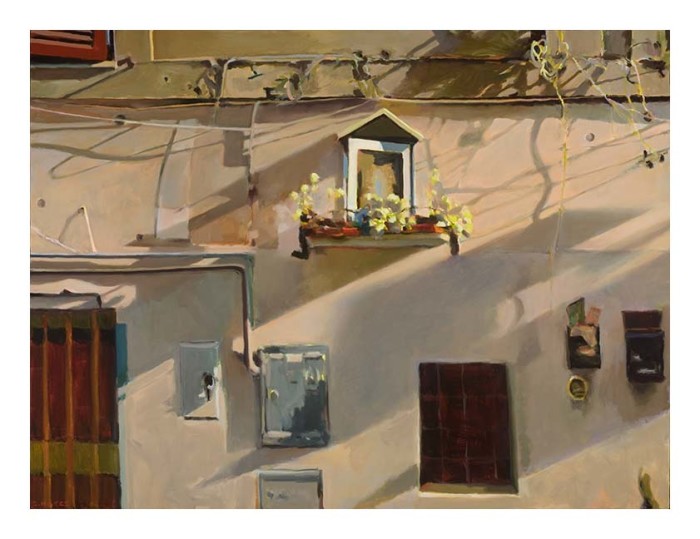

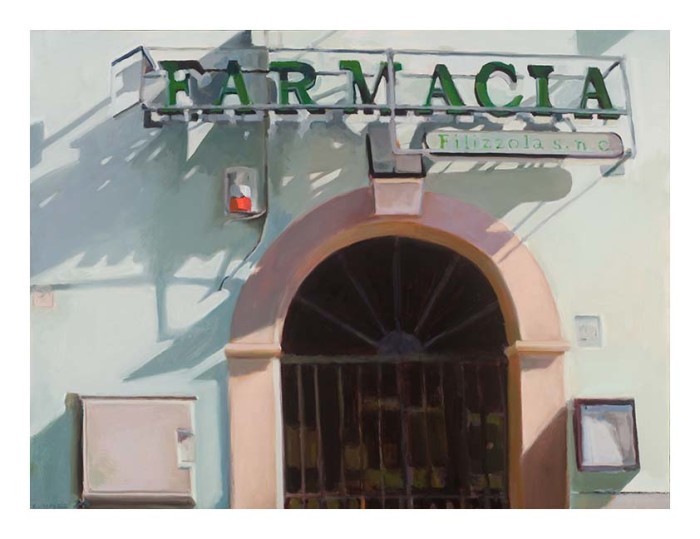

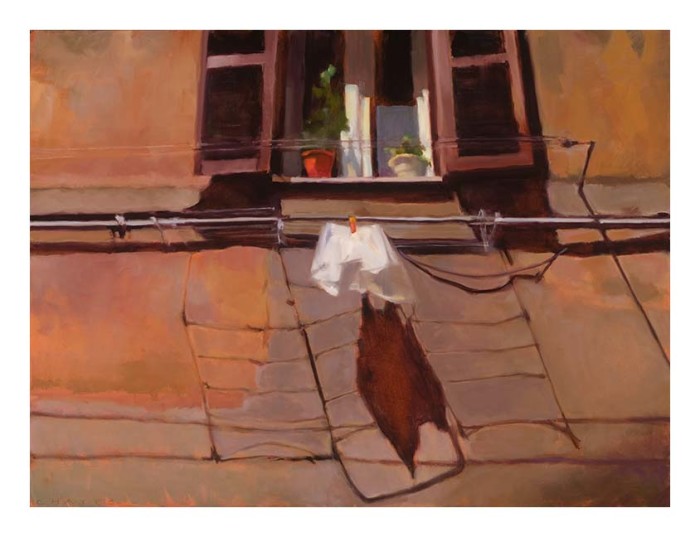

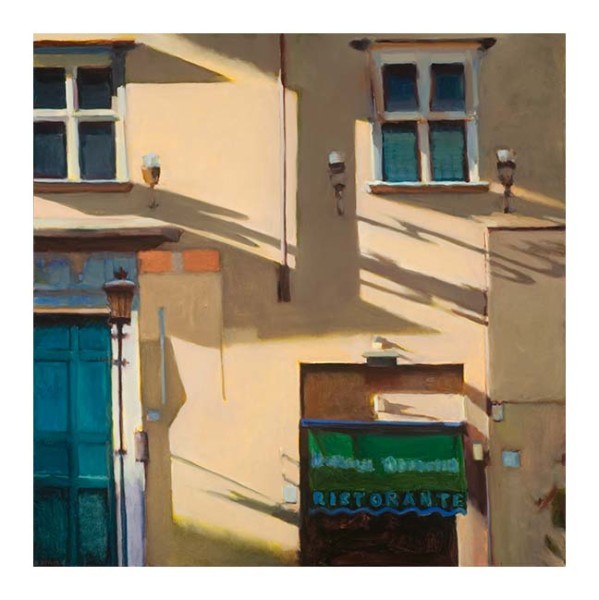

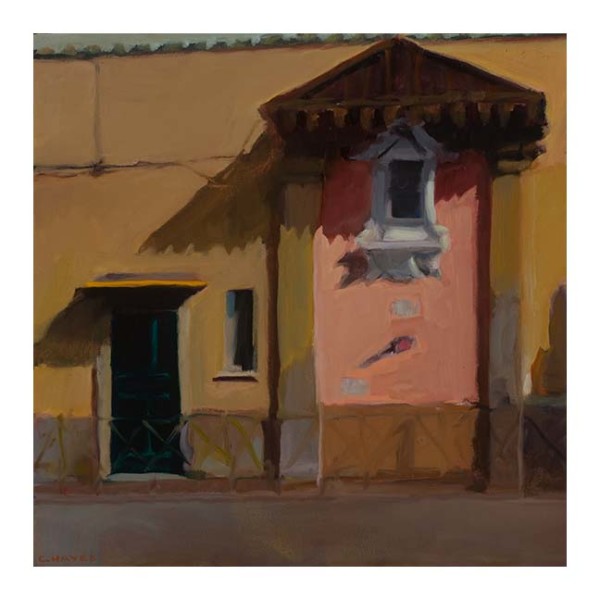

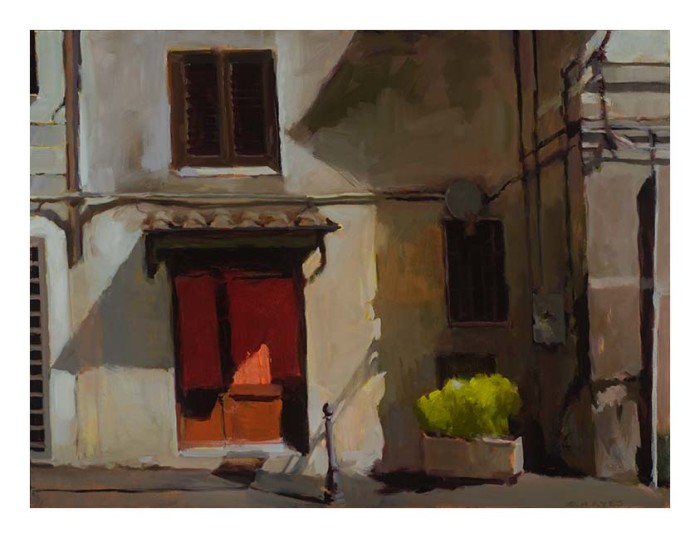

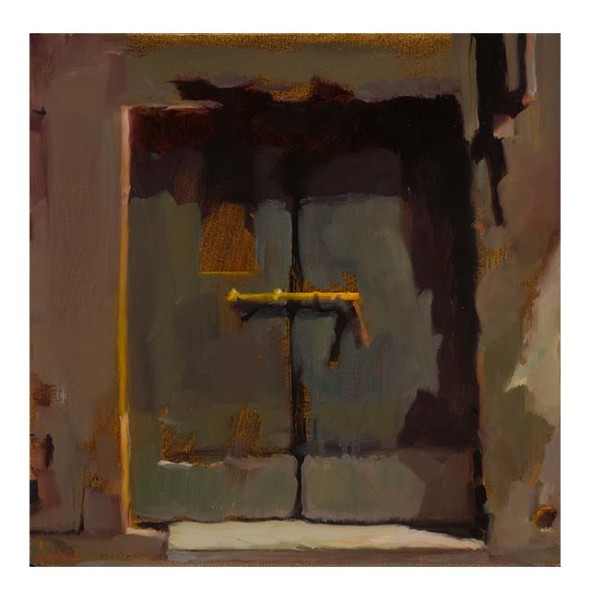

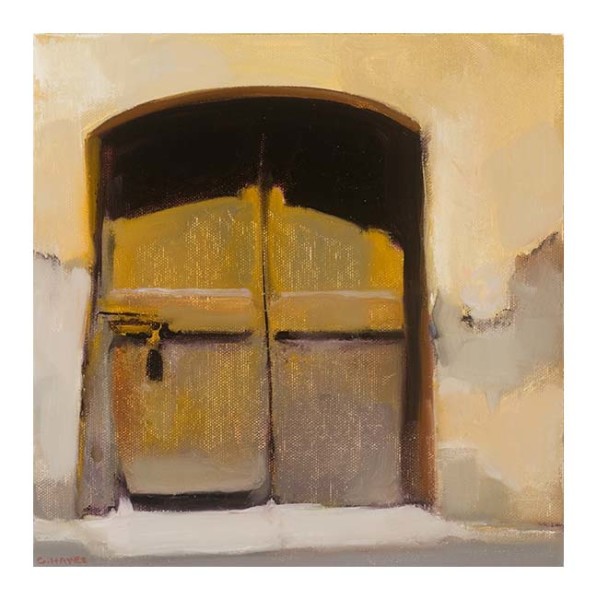

CH: Given a rooftop apartment, I looked out over Piazza Mattiotti in Civita Castellana, an old, hilltop city with a population of 7,000, an hour north of Rome. Civita is where many artists have worked over the centuries during their European “Grand Tours”. Each day I walked to class through a maze of narrow stone streets, often in deep shadow, but catching edges of light on shutters, arches, doors, utility wires, pipes, and ever-changing strings of laundry. Repeatedly attracted to the muted colors, shallow spaces, irregular surfaces, and crisp and dissolving edges, I felt inspired to paint, and to use them for teaching opportunities.

LG: Many fabulous painters from around the world joined with the JSS in Civita program to teach, study or just paint the incredible landscape. Artist talks and the discussions over meals and downtimes about differing painting approaches and philosophies have exposed many there to new ideas on what makes painting good and bad. What influenced or stood out for you while you were there?

CH: I feel deep affinity with the many painters I met in Civita. With great joy, I immersed myself with my students in the intensity of the program, in a very dramatic landscape, overwhelming the senses. Red tufa cliffs draped with lush green vines contrast with softly-colored buildings that themselves line hill tops rimmed by distant hills dominated by a storied mountain, wrapped grandly in mist. Very stimulating conversations among artists often dealt with conveying this monumental beauty in paint. Even using skills applied to familiar subjects, we were forced to rise to new challenges in this vast, historic place.

LG You often work thematically or with related subjects. What attracted you to paint these Italian façades?

CH: In teaching, I celebrated my reunion with Italy, but decades after my initial visit, and with a lot of experience, I brought fresh eyes to the subjects of these paintings. As for any borrowed view, I responded to what was unique. But special to Civita, the tangible, smoky atmosphere echoed my love for many Renaissance paintings. Paying keen attention to this special light of place brought new life to my paintings.

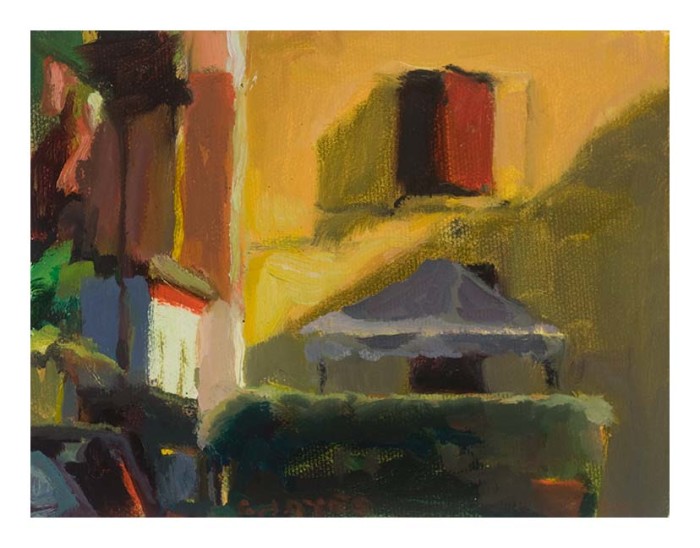

LG A strong, abstract geometry underlies your use of light and color. While many elements are clearly defined, such as laundry on a line, other elements are more abstract, mysterious. What decides the level of realism for your paintings?

CH: The tension between abstract and concrete echoes the quality of place. Life goes on all around you, in the moment. Yet, experience from the past also appears everywhere, vividly, even though less distinctly. The eye, mind, and emotions resonate to these differences evident in one’s surroundings, reflected in paint.

LG Can you describe how you develop unity in a painting?

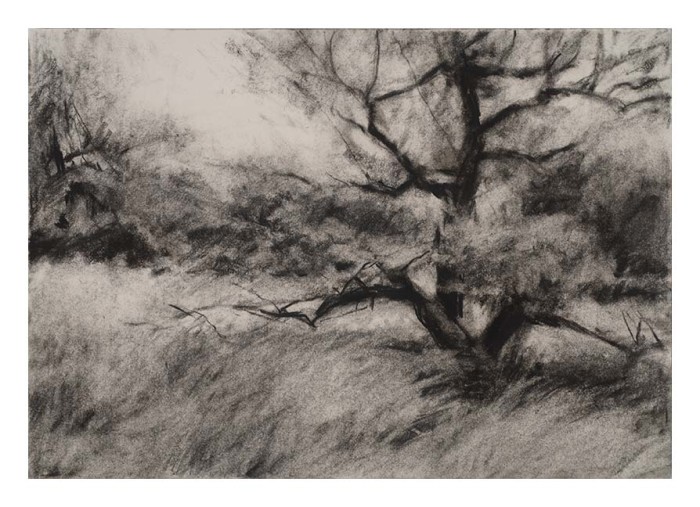

CH: Lots of scraping and wiping. In addition to my own trial and error, I learned a lot from my JSS colleagues about the quality that comes from putting aside a painting for evaluation. It may need wiping, scraping, or sanding to leave vestiges of color among fibers and weave. Repeating this process develops an accumulation of effort both in the experience and in the pigment that together make up layers of richness. Though one may not see this structure directly, the eye recognizes its richness.

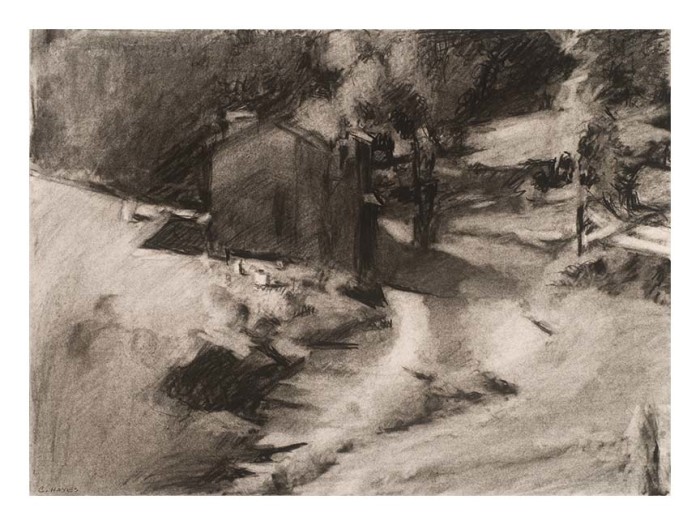

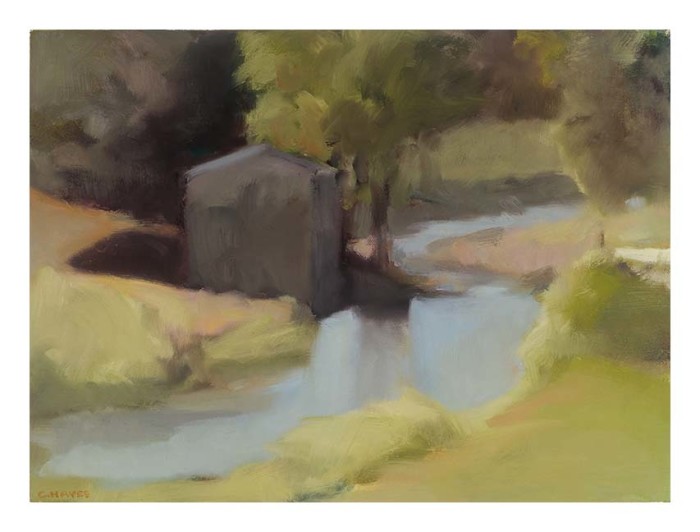

LG How do you start a painting? How much do use preliminary drawings, photography or studies with your work?

CH: I vary the way I start paintings. Back in my studio, my drawings, photographs, color studies, painting sketches, and journals often stimulate a painting. I keep ready a variety of prepared canvases, of different sizes. I usually have four or five canvases in process, sometimes even painting over old work. Occasionally, I examine a detail in a photograph, analyzing it carefully with a drawing or an oil sketch. Other times, I might simply begin a new canvas by painting loosely with large brushes, to then sit and journal, sketching possible solutions to paintings that need resolution. I trust and rely on my intuition, pulling from an inventory of sensual memories. Observation and specificity is important to me, but so is letting distance filter irrelevant details. The subjects and places in my paintings are very recognizable. You could go to Civita and find that particular yellow door.

LG Is how you found the scene important to you? Do your paintings deviate much from what the scene presented? How important is direct observation?

CH: Wherever I work I continually ask myself the question: “What is this painting about?” Sometimes, my initial answer triggers me to begin a painting, perhaps as simple as seeing a pulsing yellow glow, or being pulled on a diagonal by a shadow, or looking for details submerged in the darks. Intuitively, I love to play with the geometry of shapes and the exaggeration of color. Within the general structure of a scene, I improvise from possibilities, much as a musician improvises.

LG: You have a solo show at the Dowling Walsh Gallery in June where you will give a talk on “What is Ambition, Related to a Painting Life?” Can you say something more about this?

CH: I want to reveal how my ambitions have changed over time, using examples of my work as well as by other artists to show what ambition means to me as a painter, and how it can enhance or impair the creative process.

LG: I heard you say that when you paint, you need to see the world as if it were made out of paint. This is an intriguing notion; can you speak more about this thought?

CH: Responding additionally to one of your previous questions about how much I might deviate from what the scene presented, I do not declare, even to myself, either subject matter or intention before I begin a series. I find, recognize, and see a subject as if it is already made of paint. These discoveries arise across many subjects and topics. After I have completed whatever number of paintings, though, I look back on the group and recognize related patterns and concerns. I do not plan a narrative.

More generally, I see my daily life as the continuing opportunity to imagine my next painting. Any one subject has a lifespan based on the intensity of my curiosity. My process to follow a subject or image is the same: exploring possibility. I look for subjects that fascinate me with the challenge to find my voice in what sits in front of me, in the world and on my canvas, and to reveal its pictorial power.

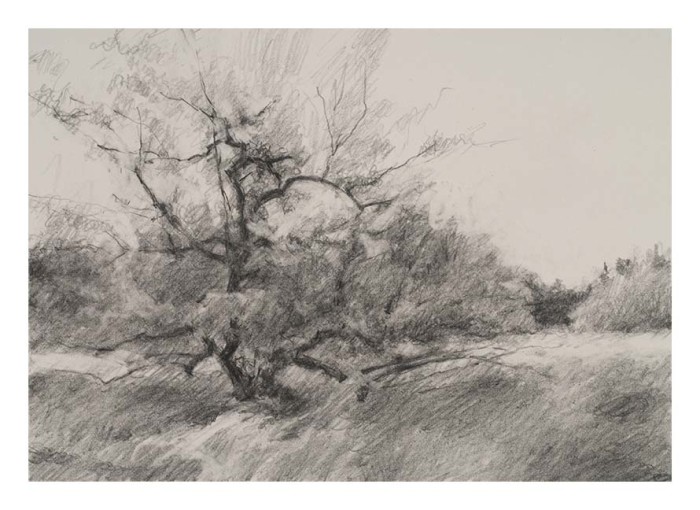

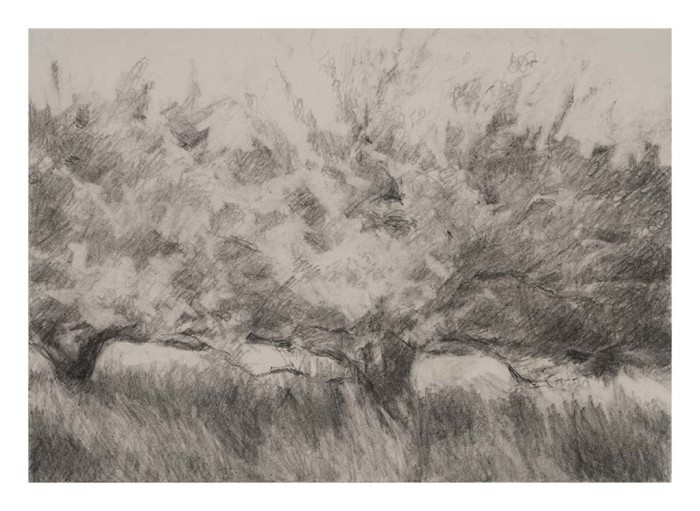

As examples, my tree drawings emerged from a Borrowed View in a large apple orchard. My studies on-site became a small series of eleven drawings. My paintings of Maine include coastal motifs, interiors, and still-lives. They all spring from specific places. My series on children-at-play developed from spending time with six youngsters over their first 14 years of life. My Italy façades respond to two very intense summers at Civita.

For all of these examples, my initial attractions to paint are visceral. They arise from glowing light, gesture, strong colors, and the geometry of design. When I reflect on a series, though, I sometimes see what might have subconsciously drawn me to their subject. I discover intention and meaning after the work mirrors to me preferences that I followed, many at levels I do not understand fully. One series shows empty chairs, another closed and locked doors, another absorption in play, another describes food and eating, and yet another floating and water. This open and continually expanding variety of subject matter frees me, in the moment, and in my growth over time. The constant for me is to translate uniqueness of place through my lens of experience in painting and living.

LG: What’s next for you? Will you be going back to Italy this summer?

CH: As to my work, I generally avoid making predictions, not wanting to constrain the impulsive freedom that motivates me. But right now, I am working on drawings of ancient architectural forms, mostly column capitals and carvings. I never know how far a series will take me. As for this summer, I feel deep reverence and affection for Italy, and I plan to return—just not this summer. Maine is too beautiful to leave for three years in a row, and I want to be here this summer to appreciate my home state with new eyes, after my recent travels.

Such a delight to read this interview. I’ve admired Connie Hayes’ work for years. I took a summer course at Maine College of Art some years ago and I think all of the students there wanted to paint like Connie. I love the simplified shapes and bold colors of these. Beautiful work.

These works are beyond remarkable….I am in awe

Hi Connie:

I have just looked at this wonderful body of work. You seem to capture the places you visit in a very strong way. Some people think they see, while others never do. You see with your eyes wide open, Connie. You make me wish I had time to paint. Hope our paths cross soon. Shirley Stenberg

One of my favorite painters and one of my favorite subjects-clotheslines. Love these.

HOLY STROMBOLI! This woman can PAINT!

Connie is one of my most favorite artists and I had hoped to attend the classes in Italy. Seeing the work she did there inspires me even more to continue working to create art from ordinary places and experiences.

Connie your work remains so powerful: loose yet structured and strong – a symphony of luscious color and swirls of paint – and I am continually inspired to keep on painting from seeing it.

The quality of light in these paintings is extraordinarily beautiful.

I am hugely anticipating the works produced by this master in “her home state with new eyes”!

I am pleased to have been directed by a friend to this interview and gallery. I have studied Connie’s book and will study these paintings as well. She is the best…palette, setting, balance, brush strokes. She has it all.