I’m pleased to present my email interview with the landscape painter Raymond Berry for Painting Perception’s new 4 questions segment. Raymond Berry is a Professor of Art at Randolph-Macon College and lives in Virginia. He has been painting the landscape from observation for more than 40 years.

Larry Groff: You often paint with encaustics outdoors; this is surprising, as you usually think of encaustics as more of a studio medium, with hot plates and all. It is less often seen with observational work. How difficult is it to paint with directly? Is that difficulty part of the appeal? How would this differ from just using a wax medium or oil paint for that matter? Can you tell us more about your setup with this and how you go about painting outdoors? What is satisfying about landscape made with encaustics?

Raymond Berry: In the 70’s, I worked with wax medium in some large paintings but eventually it drifted out of my working method. After viewing some recent gallery exhibitions, which featured some encaustic pieces, I was reminded of how beautiful the medium could be, especially with using the authentic technique that melts the pigment/wax blend. All of the work that I saw originated in the studio and was abstract, conceptual or crafty in intent. Nothing observational at all; but it was beautiful stuff. I asked myself, why couldn’t I use paint like that in the landscape? Well, because I had not seen an electrical outlet in a tree stump and extension cords tend to be measured in feet not in miles! Can’t do encaustic without a hot plate and heat guns!

I thought of plugging into the car battery or using a camp stove to heat my palette. I realized that I would be painting a palette of “color as soup”, very difficult to control. I needed to keep it simple and that’s when I realized I could treat my cookie pan much as a watercolor palette and just “wake up” my color with heat, not from below but from above with a butane torch! How hard could this be?

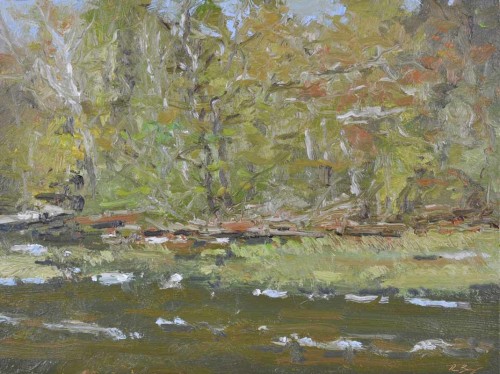

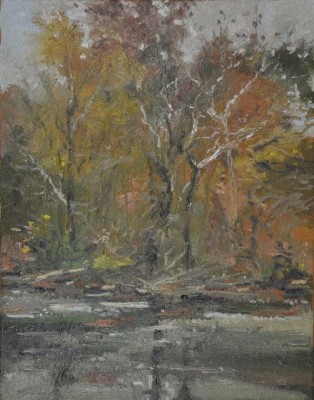

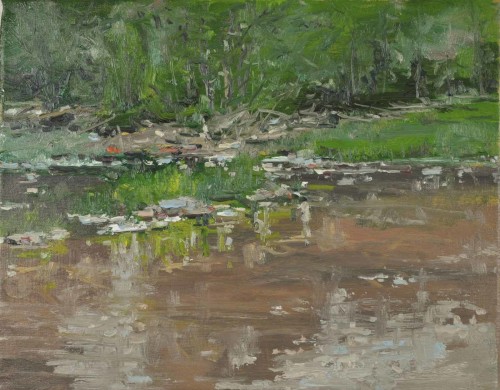

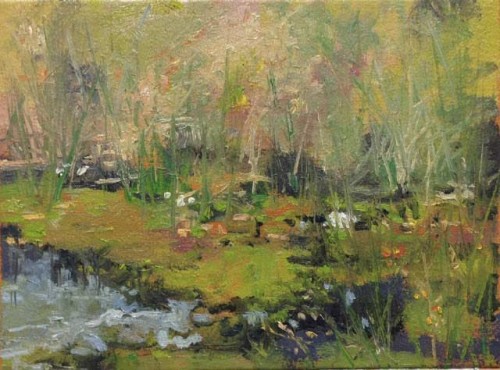

Slideshow of Raymond Berry’s Plein Air Encaustics Process

My first adventure in encaustic plein air, me “paint with fire”, was rather interesting as everything went pretty much as I planned except that I set my brushes on fire several times! I also tended to get distracted, looking at how cool my brush strokes were and then my “fire” hand would cheerfully point at something different on the panel and it would drip down the easel and out of the picture plane. I melted away some of my best efforts. Also, the brush hair didn’t catch fire; the handles went up first–all that flammable lacquer–then the hair caught on. This was painting at it’s most exciting! I was standing in the landscape making sublime observations, deeply attuned with nature and with fire in one hand and a brush dripping with hot wax–some of it was actually reaching the panel!

This process is comparable to playing a stringed instrument; each hand is functioning differently but is working together, the left hand applies the flame and the right wields the brush and paint. It takes some driver’s education to make this happen, lots of practice and burned fingers and keeps your ego back in the studio.

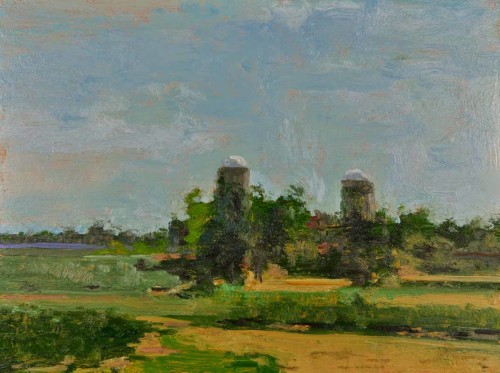

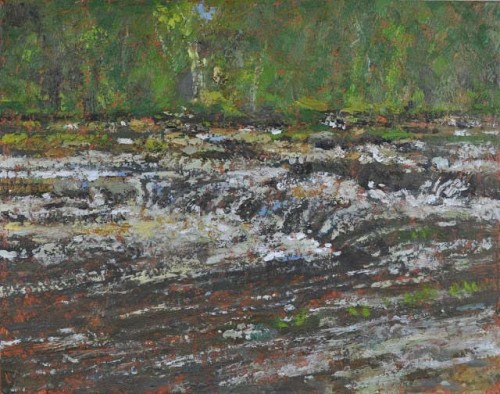

A great deal of my enjoyment of this technique has to do with some memory of abstract expressionism. There is a way the material wants to be handled that lends to abstraction and gesture simultaneously. It’s hard not to touch them, the surface is very compelling and really does lend to the painting as an object. The process just seems to fit me and also demands something that I have to work at and wrestle with in a very positive way. It certainly is informed by all those years of oil painting, but it’s a very different animal. It’s been a nice addition to my landscape toolbox and it will be interesting to see how it evolves over the next few years.

LG: What are the your most important considerations when you decide to paint a particular view? How much of this decision involves the actual scene and how much is it what you think might make a good painting? Can you explain what that means for you?

RB: That’s a great question and I honestly don’t know that there is a good answer for this. I do have some very strong ideas about what I am trying to find in the land and most of them have to do with places of “power” and lessons in the places that I find. In almost all my investigations there is something of reclamation and constant change: water is almost always present and some growth that is in flux and has some strange and mysterious complexity. I don’t seem to be attracted to obvious drama in the landscape. I do the same thing over and over looking for small dynamics and changes in relationships. I want to become a part of it. I try to understand what the landscape wants. So sometimes it gives me something right away and sometimes I have to wait for it. It takes a long time to be natural with what you do as a painter and there are days when I go out and just disappear into the whole thing and come out with a personal lesson on the canvas. I always learn something each time I go out and I try to avoid cliché and formulation. Even on a bad day, you get something worthwhile from it.

LG: What aspects of painting give you the most satisfaction? What would you say to someone who expressed interest in being a painter today?

RB: I certainly like the “completeness” of painting; there is great satisfaction in the concentration and focus you have to have physically and mentally to make things work and move toward some kind of event. You are making something each time, no matter how small. It all adds up to an understanding of something essential to living as a vital and serious person. What a marvelous investigatory and expressive method of finding your place in the world! You also leave a trail of efforts and evidence of your investigation, the good and the bad, the weak and strong things that you can look back and see how they really were. Visual artists have a great gift in that they can critique themselves by taking another look at where they have been and how they can improve and move forward.

It’s an interesting question, what do you say to someone interested in painting today? What is painting today? I don’t know. When I read reviews and commentary in many respected publications, I don’t understand the language they are using. Sometimes there are some intelligent discussions but actually I think hearing artists talk about how they work and what their aspirations are is much more meaningful than criticism and the strange way we tend to write about it. I recently spoke with an old friend that had a very solid position in the museum world a few decades ago and left it because “she didn’t understand the language they were using…it was a kind of code”. How sad is that?

I do teach painting though and that’s a special responsibility. I hope I give my students a realistic and direct way into “painting as search”. I want them to find their way to express themselves and be honest about it. I don’t necessarily teach a technique or a method. I teach them how to begin. I think that’s the best I can do. Do as little harm as possible and try to get them to respect hard work and patience. It’s pretty rare that someone comes to my classes with the hopes of being an artist (one every ten years or so). I just try to be fair and straight with them. I teach quite differently in a liberal arts college than I would in a more traditional art school. It’s a different approach to education than someone on a more artistic track. I’m all for everyone being well educated in a broad sense before moving towards a specific field; thankfully, artists have been traditionally very curious and good life-long learners.

LG: What makes some painting great and others not so great?

RB: It’s a fair question and after some thought; I may never use the word “great” again. Donald Trump has beaten it into submission. I do often tell students that something they did was “great” but in context, it’s a nice conversational word to support an exceptional effort. When I was an undergraduate, “Great Art” was most often something big. I have lived fairly close to Washington, D.C. most of my life; I grew up looking at Vermeer’s, Girl with the Red Hat at the National Gallery of Art. It’s a great painting: just 9” by 7”. Las Meninas is a huge painting and it’s so great that most people are struck dumb in front of it. Doesn’t each of us have a separate responsibility for this measurement? There are things that I can see in a painting that my students miss completely because I’m more experienced, educated and so on. It’s a real pleasure to listen to someone really knowledgeable about art talk in front of a fine work. Peter Agostini was wonderful to be with in a museum, he knew so much, but he had such poetic ways of talking about everything. I envy all those students that Lennart Anderson taught and spoke to about painting. I’m quite confident that Tim Stotz, a former student, could teach me a few things that I had not considered if I were in his classes on drawing and painting in the Louvre.

It would have to come down to some alchemy about the humanity of the artist and their willingness (or unconsciousness) to share in that vulnerable notion; like that balance and sensitivity that exists in pretty much everything Morandi did.

To look at a painting and see the brushstrokes of their decisions and revisions, their struggle to find the rightness of a moment and share that with an audience, that is something really respectful. I’m thinking of the little Vuillard in the Virginia Museum of his mother in her apartment; it’s such a fragile instant in paint.

Something incomplete or fugitive in painting can hold a clue as to the mystery and vision of another human being at their most perceptive moments. I was trapped in a huge Cezanne exhibition at MOMA in 1976, there were too many people to fit in the galleries and everyone wanted to move on. I was immobile in front of one of his works from the Bibemus Quarry. I swear that it moved in front of my eyes, it would vibrate or change somehow. I pointed it out to someone next to me, but she thought I was being dramatic and making something up to be arty . Honestly, though, it wouldn’t stay still. What do you call that?

It’s interesting sometimes when you are in a room of “great” works and the distinction becomes its own reward. I was in the Louvre in the early 70’s and I walked into the gallery where the Mona Lisa was being cheered on by about forty Japanese tourists, you couldn’t get close to the painting for the crowd. There, on the other side of the room, almost directly opposite from the camera-wielding herd, was Titian’s, Man with a Glove. No one was standing in front of it. Everyone was looking at a great work of art or a cultural icon for sure, but they were missing one of the magnificent examples of paint handling just a few feet away. I wanted to call them over just to look at the pose, the composition, the face, and those hands! Somehow, we think we know something substantial about this long dead gentleman. This is a kind of perfection. How could someone do that? I still don’t believe it!

Maybe that’s how we begin to recognize how greatness might come into our minds, as something we can’t really grasp ourselves doing. The fact that it exists helps us to see what is possible, but the wonder is that we feel gratitude that it is there for us to see and enjoy.

From from the Bio on his website: A California-born, native of Virginia, earned his B.A. in Art from the University of Virginia in 1971 and his M.F.A. in Drawing and Painting from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in 1975. There he studied extensively with Peter Agostini, Ben Berns and Andrew Martin. He joined the faculty of Randolph-Macon College in 1982, first as Artist-in-Residence after teaching positions at Wake Forest University, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and the Governor’s School of North Carolina. Despite his bad temper and facial hair he progressed through the academic ranks to become a Professor in 1998. Primarily an observational painter of the landscape, he developed a series of “rescued books” combining observed phenomena and vintage photography and has recently been experimenting with cigar boxes and other mysterious things. He has exhibited primarily in the Southeast and in occasionally in New York since the 1970’s.

Ray, your verbiage is as captivating as your art!

Thank you.

Ray. Your work in encaustic outdoors is a marvel. You took up the challenge and have made it your own. Your comments about teaching resonate with me too, first do no harm. Helping a person get beyond the cliches of vision and engage in looking at their surroundings in a fully visual way is so valuable as it opens possibly for their future to see in an un encumbered way.

I hope we cross paths again in Virginia.

Bill, Thanks so much for the comments. I really appreciate the thoughts…yes, I certainly agree that there are so many more possibilities for those that are given a solid “visual way” into things. A loss of any of those pieces can really distort a direction and a sensibility for a young artist. I had poor direction early on and it took a long time to make course corrections (although I learned even more in the process) and find something that was my own. It certainly helps as a teacher to understand these failings directly.

I do hope we cross paths soon, I have some thoughts about a project/exhibition that you might like…