by Larry Groff

Ann Lofquist, Valley Oak, Paso Robles, 2014 oil on canvas 26.5 x 34.5 inches

Courtesy of Ann Lofquist and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, California.

A couple of weeks ago I saw Ann Lofquist’s solo exhibition of recent landscapes at the Craig Krull Gallery in Los Angeles. A delightful show of California landscapes, roughly divided between views of distant urban views along the southern California coast and of pastoral areas between the Santa Ynez Valley and Paso Robles in the California interior. I am often attracted to paintings of things the way they are found in nature, respecting its subtle tones and mysterious,idiosyncratic forms. Lofquist shows remarkable depth in her visual investigations, especially with evoking the play of light during dusk and other fleeting moments. The larger sustained work pulled me closer to observe the mesmerizing qualities of the painterly touch of her brushwork and how the painting worked both close up and standing back, where the underlying structure with its pathways and rhythms of color, line and shape relationships unifies these engaging compositions.

I’m delighted to get the opportunity to learn about her work and thank Ms. Lofquist for taking the time out of her busy painting schedule to answer some questions I sent to her by email.

Palisades Late Afternoon, 8.5 x 13 inches o/panel 2013,

Courtesy of Ann Lofquist and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, California.

Larry Groff: Please tell us how you to decided to become a painter and who or what have been some of your greatest influences?

Ann Lofquist I attended public school in Bethesda, Maryland, and while in high school I was fortunate to have an exceptional art teacher named Walt Bartman. It’s fair to say that he significantly influenced the direction of my life. As students we were encouraged to paint perceptually, in acrylics. I remember sensing that my eyes were beginning to really see for the first time and that the world was beautiful. It was like first love.

LG: What was art school like for you?

AL: I attended Washington University in St. Louis, which is has an art school incorporated into a larger university. In college we were allotted individual studio spaces, and I was conditioned to believe that the studio is the setting where art should be made. Most of us were abstract painters at that time (early eighties.) I remember that we were preoccupied with trying to do something which was stylistically new — in fact, it was almost an obsession. The problem was that we were looking at other art for inspiration, and naturally our work ended up being very derivative.

However, art school was where I developed the discipline to sustain the development of a painting over a long period of time. I was also introduced to oil paints, which continue to dazzle and bedevil me to this day. In my studio work, I still retain something of the organic working process of my abstract paintings, where the final image is the result of trial and error, addition and reduction, etc.

When I left art school, I worked a couple of years before going back to grad school. When I was working in isolation, I realized that in order to sustain me, my paintings had to directly address my visible surroundings. I also realized that I had lost something of the joy and wonder I experienced as a high school painter. In grad school I came to the realization that landscape was going to be my subject, but I had forgotten what it felt like to work outdoors. I was trying to invent complicated landscapes in the studio without the visual store of information acquired from direct observation. Since then I have tried to find a balance between perceptual and studio painting.

LG: What sorts of things do you look for in nature and what determines your selection? How much does your initial selection determine your final composition?

AL: I think many of us have had the experience of a stab of joy and longing when looking at nature; I certainly have and I’m trying to recapture those moments in my paintings. I’ve found over the years that I unconsciously gravitate towards certain subjects: a certain scale of space (not too vast) which I think is accessible to the human scale. I am also attracted to a landscape which has been shaped by the human presence. Over and over again I’m moved to paint old trees, roads, streams, tracks in the fields or in the snow, and erosion. Many of these subjects are evocations of the passage of time, and I suspect that’s why they move me.

I also prefer the light of the late afternoon/early evening, probably for the same reason. Painting in the morning is problematic for me because I’m a night-owl and hate to get up before dawn. I’m also more attracted to the sense of emotional reflection suggested by the end of the day.

When I go out to paint, the selection of a site is often a long and difficult process — I am looking for a certain combination of subject, space, and atmosphere and have spent countless hours driving up and down country roads looking for the right spot. Once I find a site which pleases me, I tend to go back many times and paint it at different times of day, different seasons, etc. This kind of intimate association with a particular place often bears fruit when I begin studio canvases.

As an aside, the DeLorme Company prints wonderfully detailed atlases (including topography and vegetation) of each of the fifty states. I’ve found them to be an invaluable resource.

LG: Do you use the viewfinder and/or thumbnail drawings?

AL: I don’t use a viewfinder or do thumbnails; often I find myself with “composition regret” when I get a painting back into the studio. However, I usually go into the field with several panels of different dimensions so I can choose a rectangle which suits a particular view. Panels are also convenient in that they can be cut down and resized. Of course, If I’m going back to a familiar place I know in advance what kind of panels to bring.

LG: I’ve read that your larger studio paintings are based on smaller paintings done from observation. Do you make these plein air studies with the big studio painting in mind or do you just paint what captures your interest and then later select out one you think would work for a larger painting.

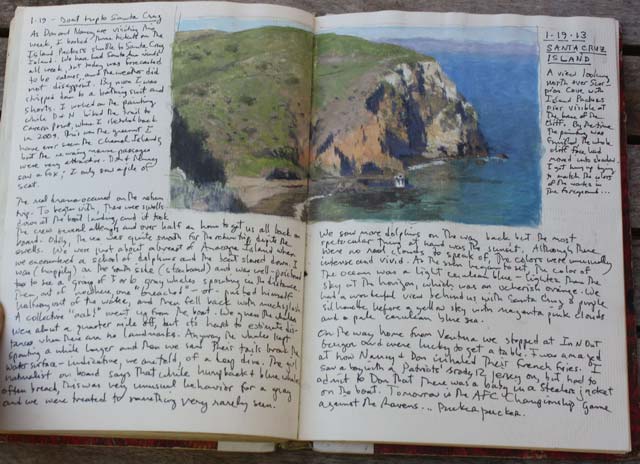

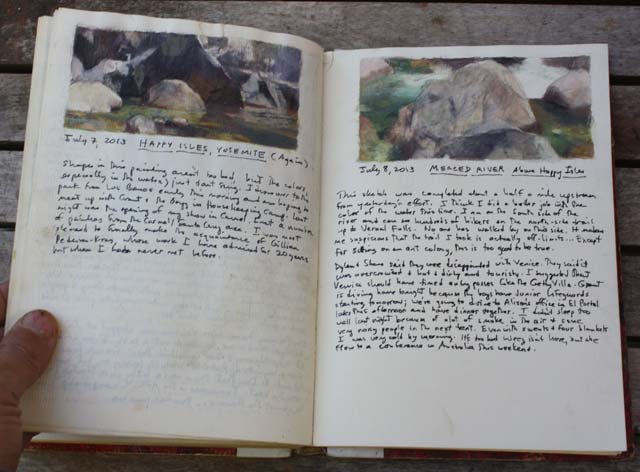

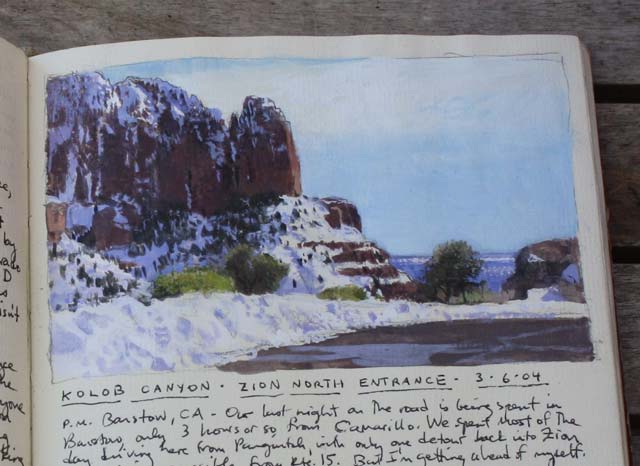

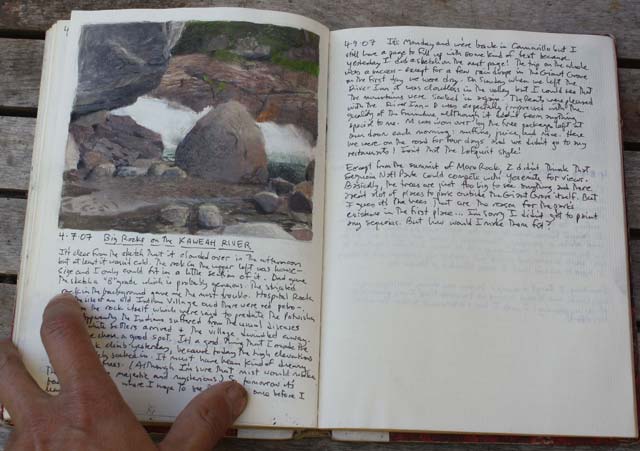

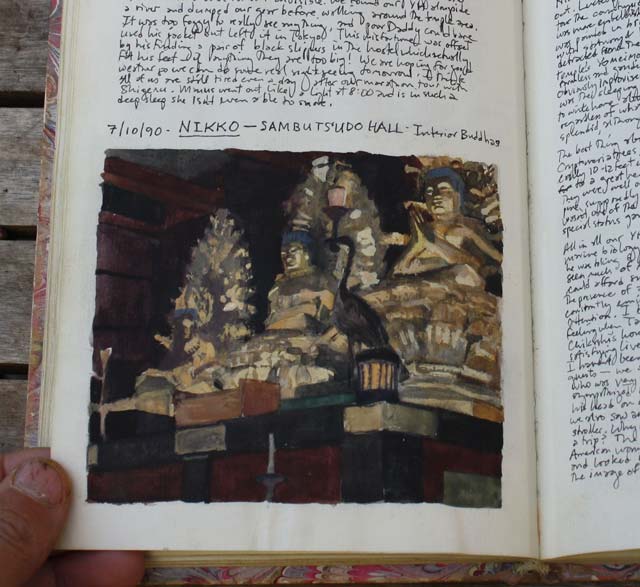

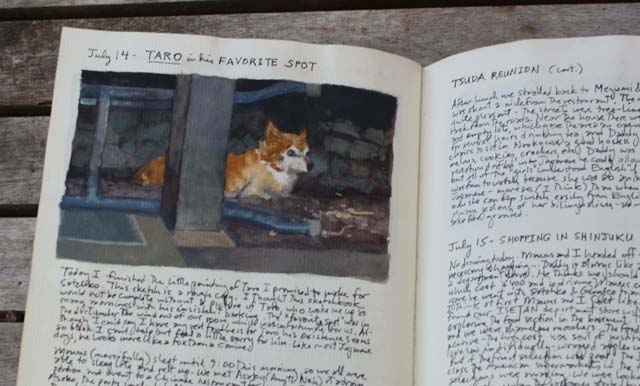

AL: When selecting a site for a plein air painting, I definitely consider whether or not it has the potential to “bear fruit” and become a studio canvas. Often times I pass on painting an appealing subject because I know I wouldn’t want to develop it into a larger painting. However, sometimes when I’m not able to travel with oils, I paint in watercolor and gouache in a hard-bound sketchbook. When working in this format I feel free to paint anything that catches my eye — interiors, people, pets.

sketchbook entry

sketchbook entry

LG: Can you tell us something about your process? Do you work from photos as well as your studies?

AL: All of my large paintings are based on perceptual experiences. I have a wall in my studio which is covered with plein air panels from which I derive my studio work. I do find photographs to be useful in supplying me with an extra level of detail (especially when dealing with architectural elements.) Perhaps my equipment is not the best, but I can’t rely on photographs for reliable color information. I have tried to do large paintings solely from photographs, but they were a failure. For me there’s no substitute for the rigorous observation of perceptual painting.

LG: How much do you work out the drawing before starting in with color?

AL: As a rule I don’t draw at all (if one defines drawing as working in black and white.) Even my sketchbook is filled with tiny little watercolors. When beginning an oil painting, I might sketch in a few reference lines but I start blocking in color almost immediately. I usually don’t have problems with proportion/placement if I keep to painting shapes. When painting plein air I work on plywood panels with a colored ground, usually gray or brown. The only time I work on a plein air more than one day is when I’m painting at dusk when the light effect only lasts a few minutes.

In the studio, when I’m reinventing my plein air experiences, I start by simply copying the small study I’ve chosen onto a larger canvas. Early on I’ll use large brushes so I can cover a lot of ground quickly. Once again, I do very little delineation and start blocking in color from the start. The studio paintings are really the result of a trial-and-error process and go through many revisions. Often I find myself moving away from the original perceptual source and begin to invent/alter the original subject. If the surface gets too built up, I’ll go in with a palm sander.

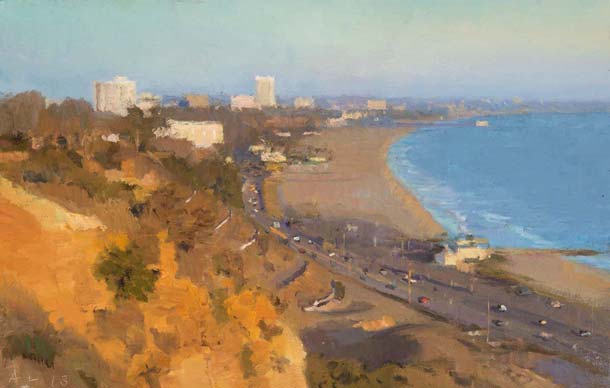

Since moving West, I’ve begun a body of work dealing with the urban sprawl of Southern California. I’ve found that painting subjects with lots of architecture really cramps my style… I have a very poor capacity for inventing buildings (I’m pretty good with trees and natural forms) and I have to rely on reference photos more than when I’m painting pastoral subjects. I’ve painted some Los Angeles vistas and I feel a responsibility to paint specific buildings accurately and that limits my ability to change or reinvent my subject as I might like.

LG: What colors do you put on your palette?

AL: My palette is pretty simple: titanium white, ivory black, burnt umber, burnt sienna, sap green, cad. lemon, yellow med, red and orange, yellow ochre, diozaline purple, ultramarine blue, cerulean blue, and some kind of rose/alizarin. (Pretty much your basic art school palette except that I’m too cheap to buy cobalt blue.) I won’t use any of the pthalo dye colors — their tinting strength is just too strong for me. My brushes are all the cheapo soft nylon types from the craft store. I leave them standing face down in the turp jar — I never clean them — and they get distorted into an interesting cauliflower-type shape which I love for getting soft edges. I also paint on an oil ground applied with a knife over a rabbit-skin glue sizing.

painting a study on site

sketchbook entry

One last peculiarity of mine is a dislike of easels. In the studio I mount my canvases on the wall. When working outdoors, I prefer to sit on the ground where I often rest my painting arm on my knee. I find this gives me more control over the brush. In bad weather (or bad neighborhoods) I’ll paint in my car, with the panel balanced on the steering wheel and my palette on the passenger seat.

LG: Some outdoor painters say the visual excitement of changing light and the surprises of nature infuses life into their painting. How do you generate excitement in the studio and keep the painting fresh and alive?

AL: Of course, the ever-changing subject is the great challenge of landscape painting. When painting outdoors I feel a manic urgency to absorb as much information as I can as quickly as possible — a kind of hyper-concentration — and I suppose this results in a kind of vitality in the painting. In the studio, freshness is not a big priority for me. I think of plein air paintings as having the “freshness of youth” while studio paintings can have a more mature kind of beauty born from slow consideration.

LG: What excites you most about painting?

AL: When I was teaching, I used to tell my students that for artists the important thing is to know what you love. Then it should be clear what it is you want to paint and what you intend to say. This is all very glib — knowing what you truly love is not as simple as it sounds, regarding people as well as painting! However, in my own case I mentioned that stab of joyous longing which I sometimes experience when I see something wondrous in nature. Painting can make that sentiment durable. I think that is where my heart lies.

LG: Many California plein air landscape painters go for a quick, impressionistic painting with broad strokes and vibrant color. Both your studio and outdoor work seem slower, tonal, restrained and carefully studied, perhaps more in the tradition of George Inness, John Henry Twachtman, Frederic Church or Corot. I understand you moved from the East Coast to California just a few years ago.

Do you think your work has changed much from this move? Can you say something about what differences you’ve found in East vs West Coast painting?

AL: It’s important to me to paint the surroundings of my current life. (Friends have encouraged me to take a trip back East to do some plein airs and do some more New England studio paintings, but that just wouldn’t feel “honest” to me.) So of course my work has changed — I’m trying to come to terms with a whole new subject. I tell myself that it’s good to get out of one’s comfort zone, although I moved to California for family reasons, not artistic ones. I miss the New England landscape terribly and often dream of it.

Recently I’ve been working on two bodies of work. One is of pastoral scenes based on midcoast vistas which are a little reminiscent of my East Coast paintings. In New England I loved painting in the autumn and winter. Here in California when the trees are losing their leaves in December, the grass is just waking up and turning green! The other body of work is of more urban views. I’m attracted to the margins where the city meets the native chaparral and coyotes and mountain lions live within sight of ten million people. I’ve also become enamored of night vistas. The light in Southern California is very distinctive and beautiful, especially at dusk. When in New England I often painted pasture streams meandering through fields. Here in CA our streams never seem to have water in them… highways at night have replaced streams in my paintings as metaphors of time and life’s journey.

LG: Would you say there is greater or less appreciation for landscape painting in the West Coast art world?

AL: I really don’t have much to say about East vs. West Coast landscape painting. I think there’s good and bad painting to be found everywhere.

LG: Many landscape painters are concerned with getting at the truth, capturing essential qualities of a place in paint, getting exactly the right color and right drawing. The truth often differs depending on the artist. If Corot, Cézanne, Van Gogh all made paintings in exactly the same spot, obviously each painter would have made completely different but equally truthful paintings.

What does being truthful in painting mean to you?

AL: When I’m painting perceptually, my primary concern is to capture the combination of light, space, and form as faithfully as I can. If I end up with a little panel which I can put a frame on and exhibit and sell that’s a nice byproduct, but I think the real purpose is data collection. After choosing a subject and composition I’m not thinking about stylistic choices — the process is as unselfconscious as I can make it.

When I reinvent the images in the studio, this “data” is filtered through my personal sieve of experience and emotions and resembles more a depiction of a memory of place. When I get it right, I hope people seeing my work experience a “shock of recognition” of a real memory in their own lives, and that my paintings might enrich their future perceptions. I considered it the highest compliment when a friend told me, “the light last evening made me feel like I was inside one of your paintings.”

LG: Cézanne was known to have been critical of Impressionism at times and instead advocated “something more solid and durable, like the art of museums.”

Do you think there is a danger that the impressionistic plein air painting in going for sensation sometimes risks losing a formal structure?

AL: It’s hard to find fault with the best Impressionist painting; maybe its very accessibility prejudices people against it. However, like Cezanne, I am inclined more towards architecturally-inclined paintings. (I don’t mean “architectural” in the sense of painting buildings, but in the construction of space.) Bellini, Brueghel, and Poussin are my personal triumvirate. For me, working perceptually/responsively is essential to my process but not sustaining enough in itself. I also feel the need to construct. My challenge (unlike Cezanne’s) is to marry the architectural construction of a painting with a naturalistic evocation of light.

LG: Do you teach workshops or at a school? What advice would you give to young painters?

AL: I taught at Bowdoin College from 1990-96. Since then I’ve been “downwardly mobile” (another way of saying “painting full time.”) I’ve never thought to give workshops.

As I see it, young painters have to make a choice as to whether their work is going to be cynical and/or silly, or in earnest. I see this as the real divide in the art world today and unfortunately most of the financial success is in the first camp. I think art can be much more than a distorted mirror held up to reflect the shallowness of our popular culture, and I would encourage young painters to dare to take themselves and their ideas seriously.

At the risk of sounding like an old fart (I just turned fifty) I would also repeat to young painters two bits of advice which were given to me long ago. One teacher (David Lund) admonished us undergraduates to develop a work ethic combining intensity and sincerity. He told us that having a career in the arts is a great privilege, and that it was our duty to honor that privilege by never being half-assed about any aspect of our work. (Somehow I imagine David said it more eloquently than I just did!) My grad school advisor Bonnie Sklarski wisely told us that, “If you’re bored in your studio, it’s your own fault!”

Ms. Lofquist is represented by the Craig Krull Gallery in LA, Winfield Gallery in Carmel-by-the-Sea, CA and Gross/McLeaf Gallery in Philadelphia, PA she received her MFA from Indiana University in 1986 and her BFA at Washington University in St. Louis. She has had solo shows in numerous galleries including Skidmore Contemporary Art-Santa Monica, Spanierman Gallery- New York, Hackett-Freedman Gallery-San Francisco, Tatistchef & Co., New York

sketchbook entry

sketchbook entry

sketchbook entry

Wonderful interview with one of my favorite landscape painters.

In case people don’t know, Sap Green is usually made with Phthalo Blue and some kind of Yellow. In most cases it’s Isoindolinone Yellow. This can vary as some paint companies use Phthalo Green in the mixture, such as Talens/Rembrandt.

Nice interview. Terrific work.

I’m glad to see that Ms. Lofquist has found the kind of fresh subject matter that can either invigorate an artist’s vision or diffuse it. (In Ms. Loquist’s case, I think there’s any question about the chemistry she has found as well as what she’s done with it.) I was dazzled by her spatial intelligence from the very beginning. And while California is supposed to be luminous, she’s made its purple ochres and powdery aubergines her own. I’m also thrilled that she’s found in the later hours a congenial companion. Her paintings of coastal commuting are, in my view, among the most powerful she has, as a New England transplant, done.

She doesn`t wash her brushes! Me neither! That disgusting job just kills the joy! I enjoyed hearing about her process and seeing the evocative work.

Great post. Amazing work. Still seems so challenging transferring those paintings on location into large studio paintings that retain the same freshness. Impressive!

Thank you for this great interview with Ms. Lofquist. I have admired her ability to paint air for a while…and now the very different feeling of California atmosphere. Even seeing these works on a monitor, they have the power to put me there.

I’ve admired Ann’s paintings since I first encountered them (in New England of course) years ago. Thanks for publishing this interview.

wow, beautiful paintings! amazing. thanks for sharing Larry!

Wonderful conversation, thanks so much for the post. Ann, your piece that begins this article; Valley Oak, Paso Robles is along with numerous others, a real beauty! I instantly fell for elegant blue above that pours towards the lovely sage green draping from the oak. Thanks for including so many photos of your wonderful and ongoing sketchbook practice. Best wishes!

Thank you for an informative and inspiring interview, Larry and Ann. Wonderful to see the sketchbook pages in combination with the plein air studies and studio compositions.

Very good work.This is the first I’ve seen it. I like the distinction made regarding the 2 types of artists.

Beautiful work and excellent interview. Thanks for posting it.

This is the first time I’ve seen Ms. Lofquist’s work. Great Stuff. Her paintings remind me of Maxfield Parish’s later work esp the composition and tree foliage. I’m wondering if he was an influence?

I’ve read this interview and looked at the pictures several times. Such a good way to get to know Ann’s work and process intimately. Thank you!!

The understanding of tans and grays is a lifelong pursuit very nicely handled by Ms Lofquist’ passages in creating emotional content,,, sense of place and the quiet solid serenity of the ordinary,,,

A great interview with a truly wonderful painter. I love how Ann always seems to find beauty in such unique and unusual motifs, particularly those in dusk and twilight. A stream of tail lights glowing in the fading light. An urban night scape seen from afar. Or her “Last Light, Old Snow” painted at the Bowdin campus over twenty years ago. They are serene, contemplative, and authentically personal. I have come back to this interview many times for inspiration. A real gem, and a very useful document. Thanks for posting it Larry!

I met Ann this evening with her lovely mother. When I found out that she was an artist, and did my favorite type of painting…oil landscape…I could not wait to look her up on the internet. I have to admit that I am impressed with her work, and how she has captured the beauty of the West Coast, especially considering she came from a very different environment. I am going to dig deeper so I can see the fully spectrum of her art, but from this quick look…I can see that she is a very talented woman/artist! What a treat!

Great work.very Whistler-esque