I’m honored and very pleased to have interviewed the distinguished painter Ying Li with an audio podcast that you can listen from the links below.

The above image links to download the audio podcast to your computer

The play control below is for the Streaming Version

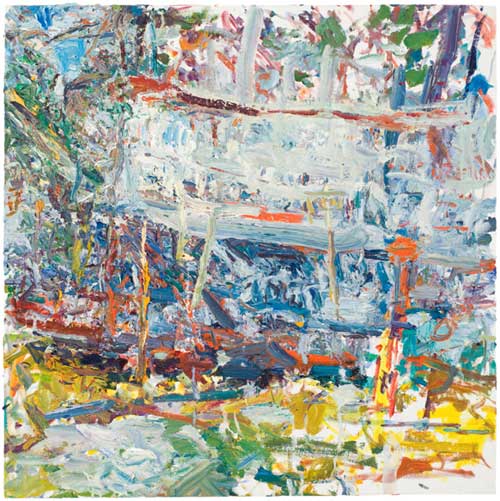

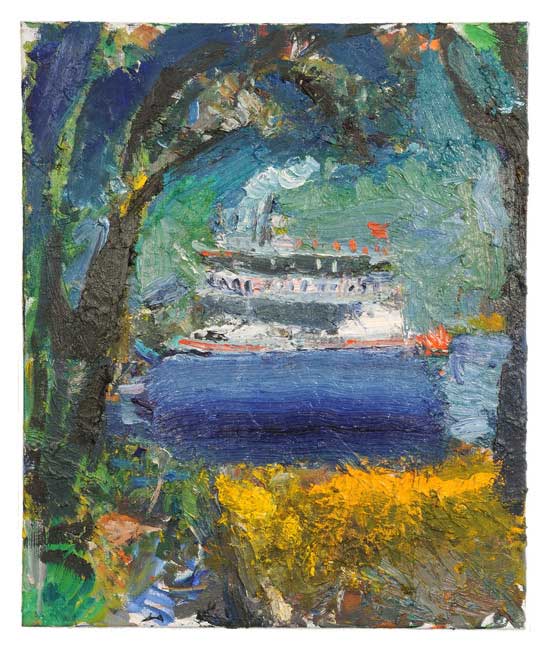

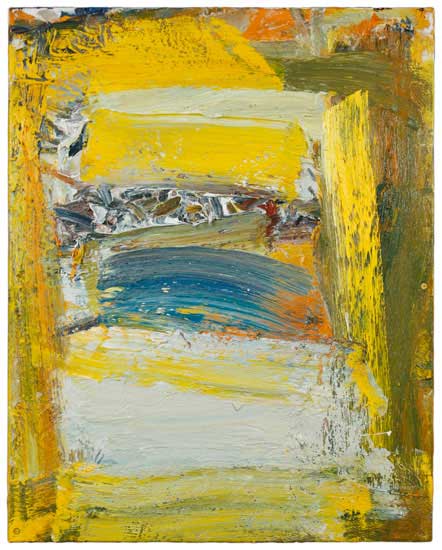

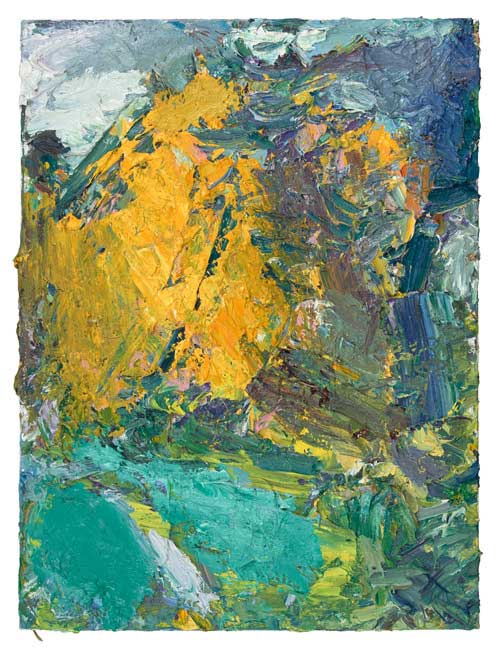

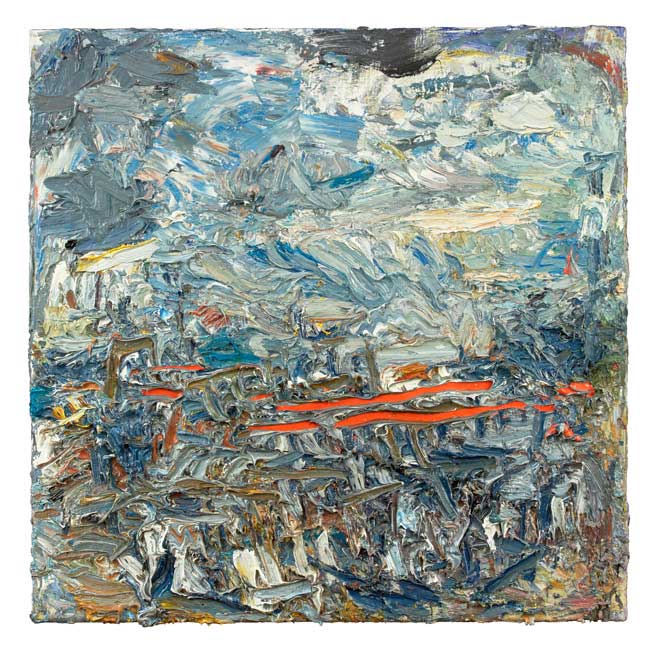

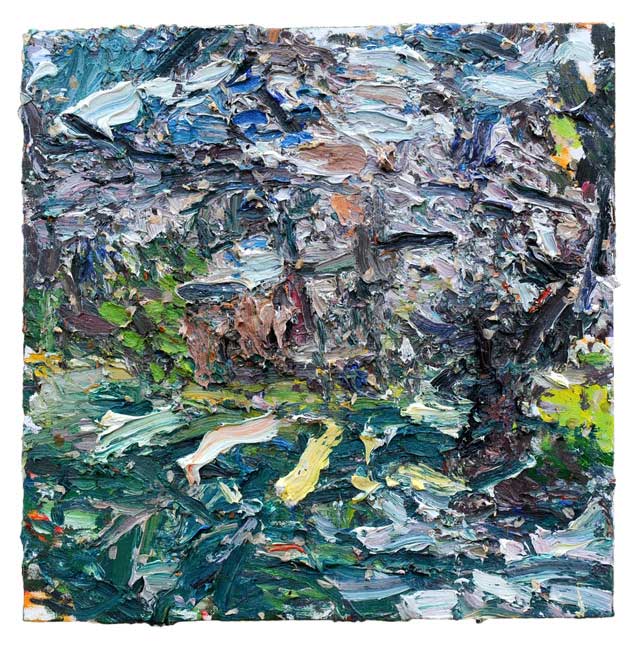

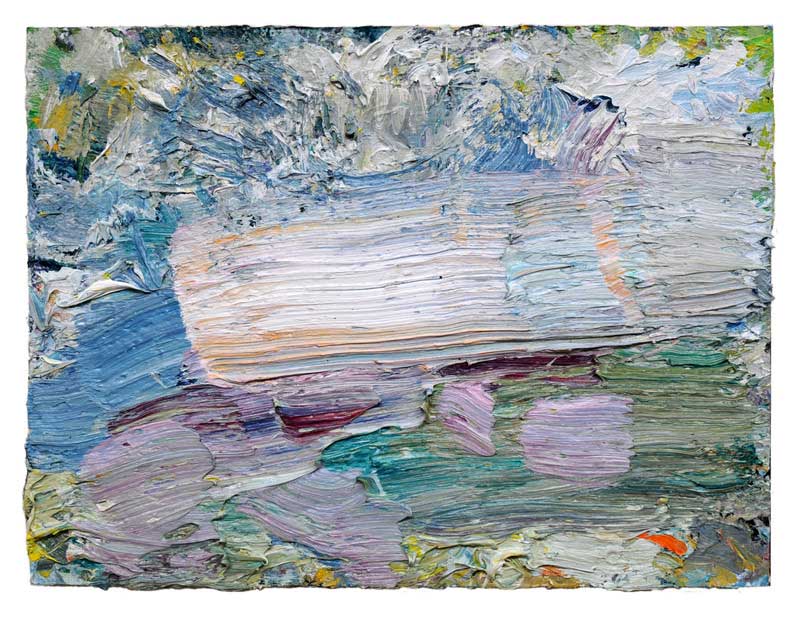

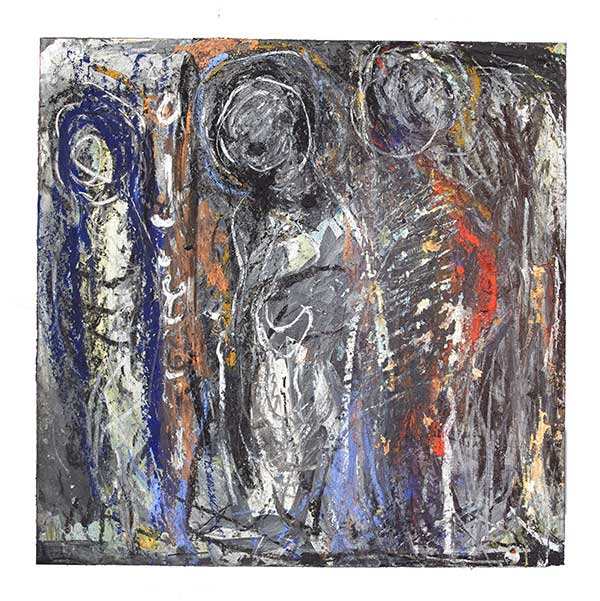

The edited, written version below of our skype conversation was made just prior to the start of her solo exhibition at the Haverford College titled Geographies, which is up until October 7 when it moves to the Sordoni Art Gallery, Wilkes University, October 25–December 18. This exhibition includes more than 100 paintings and drawings that Ying Li has done over the past four years.

Geographies, Installation Shot

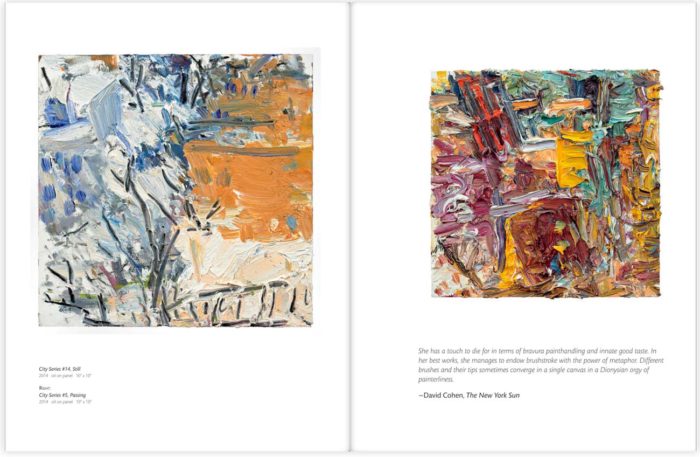

Ying Li was born in Beijing, China, and graduated from Anhui Teachers University in 1977 before immigrating to the United States in 1983. Her numerous one-person exhibitions include those at the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, Lohin Geduld Gallery, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, The Painter Center and Bowery Gallery (all New York City), and in college and university galleries at Dartmouth, Swarthmore, Haverford, Bryn Mawr, the College of Staten Island and the Big Town Gallery, Vermont. Her work has also appeared in numerous group exhibitions, including those at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, The National Academy Museum, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, Lori Bookstein Fine Art, Kouros Gallery, and Hood Museum of Art.

She is the recipient of Henry Ward Ranger Fund Purchase Award, Edwin Palmer Memorial Prize for painting from the National Academy Museum, Donald Jay Gordon Visiting Artist and Lecturer, Swarthmore College, McMillian Stewart Visiting Critic, Maryland Institute College of Art and Artist-in-Residence, Dartmouth College. Her other Residential Fellowships include: Centro Incontri Umani Ascona, Switzerland; Valparaiso Foundation, Spain; Tilting Recreation and Cultural Society, Fogo Island, Newfoundland; and Chateau Rochefort-en-Terre, France. Li’s work has been reviewed in numerous publications including The New York Times, The New Yorker, Art Forum, Art in America, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The New York Sun, New York Press, Cover, Artcritical.com and Hyperallergic.com. Ying Li is Professor of Fine Arts and Department Chair, Haverford College, PA

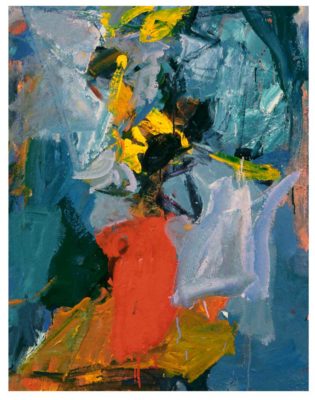

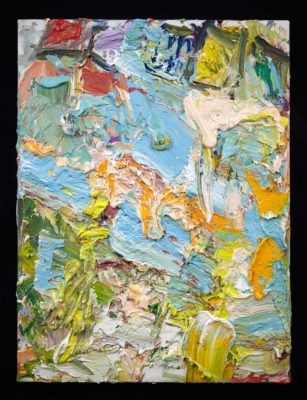

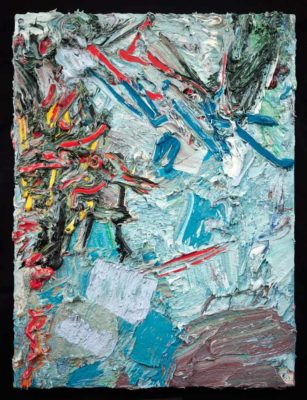

“…In the last century, perception and abstract construction were so convincingly severed by modernism that a natural integration of the two now feels nearly beyond reach. Language and ideas have replaced seeing as the primary impetus for much of today’s abstract painting, while many of today’s figurative canvases too eagerly declare their abstract formal achievements.

Through her simultaneous sensitivity to material and motif, Li unites the tradition of perceptual painting with the language of Abstract Expressionism, perhaps better than any painter working today. Her paintings return a fullness to the art, reconnecting to a painterly lineage that includes Pissarro, de Staël, Soutine, Van Gogh, and Monticelli – a tradition of painters for whom physical and visual sensation are one and the same.” – Brett Baker, Painter’s Table, May 2, 2014.

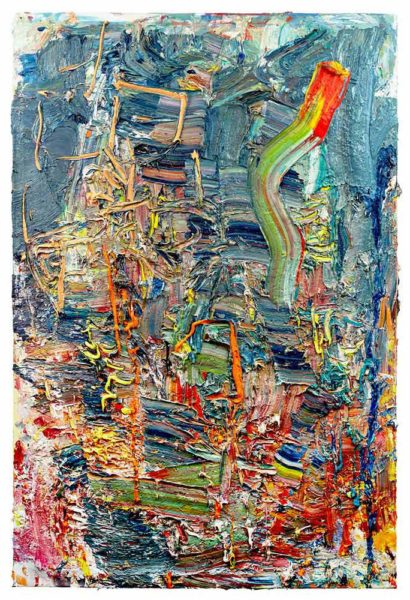

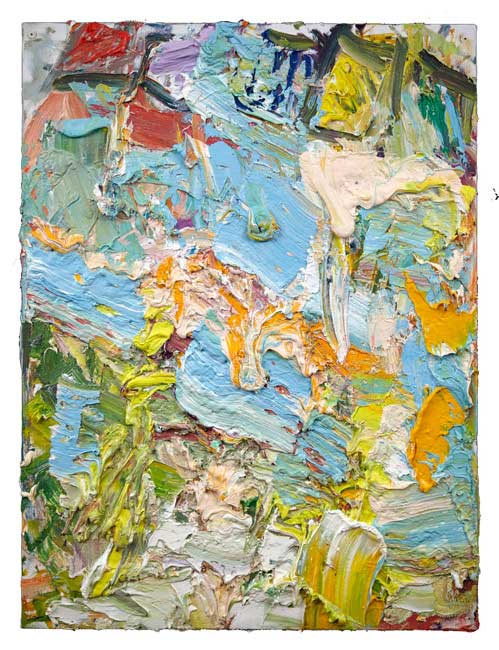

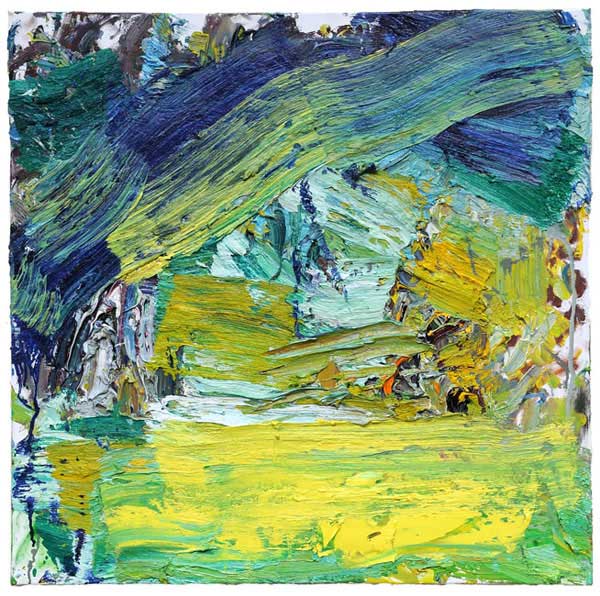

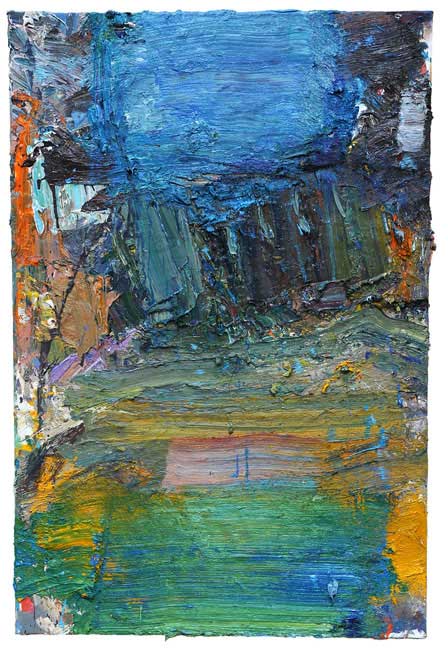

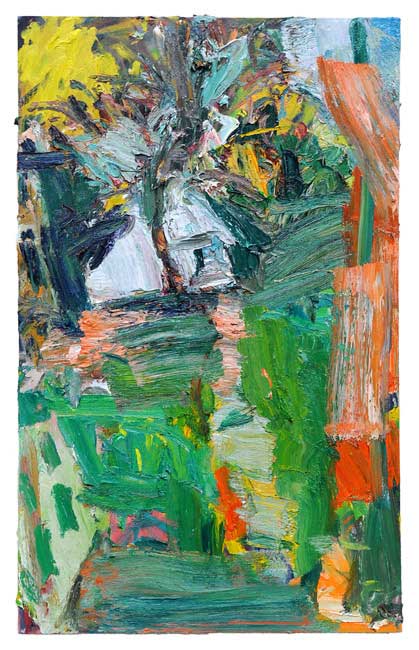

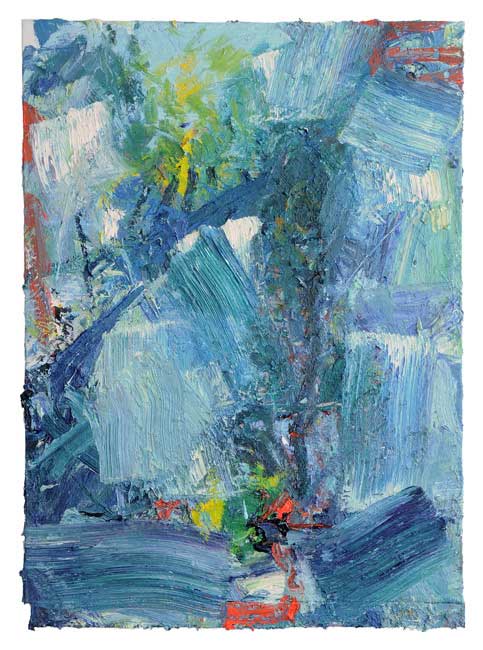

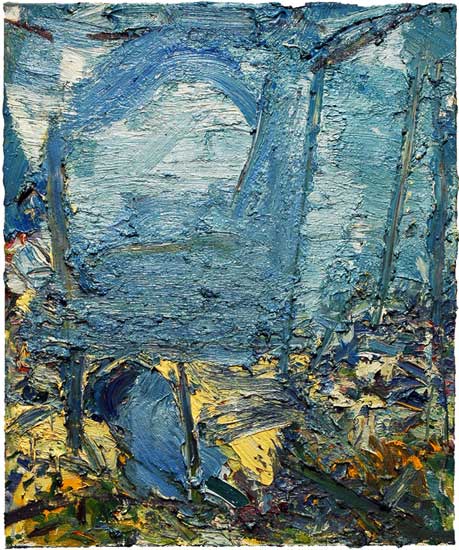

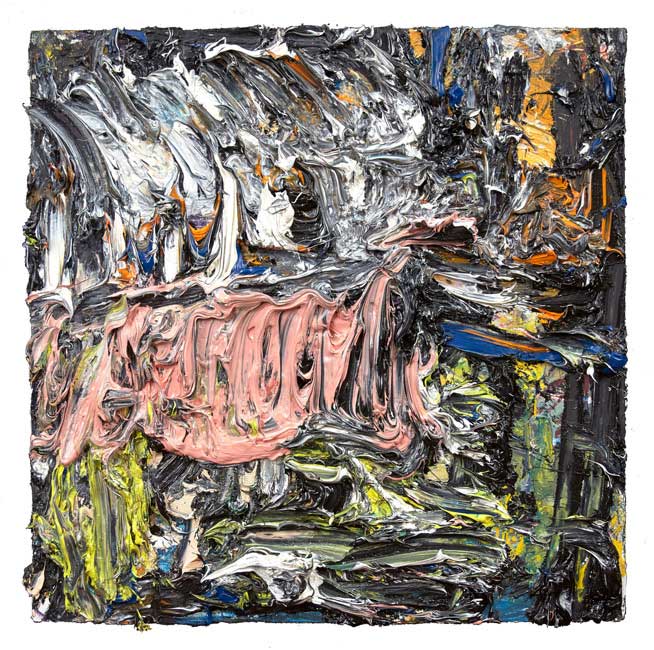

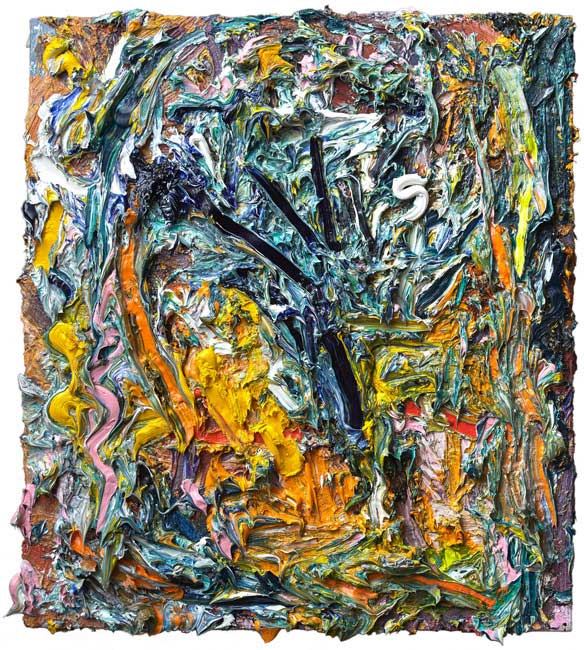

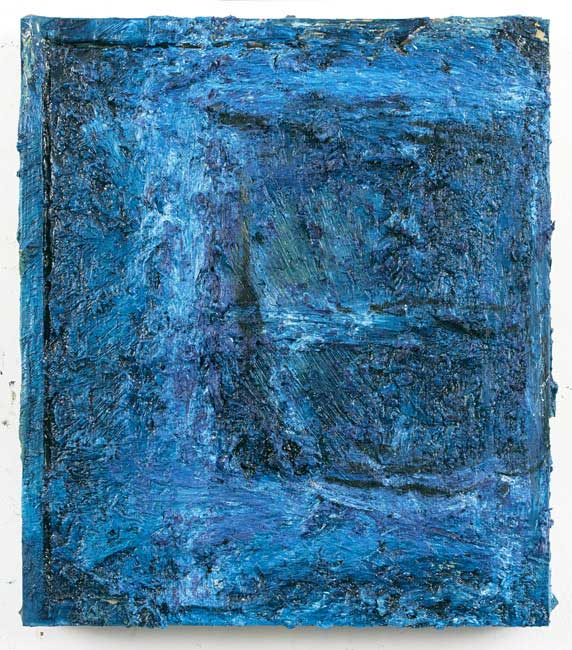

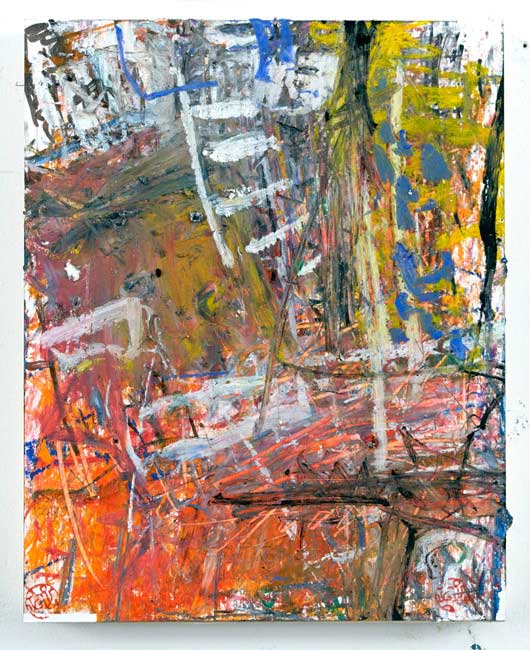

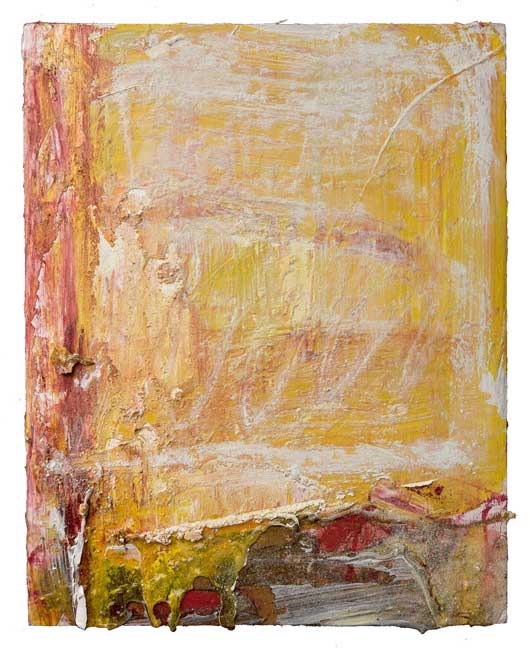

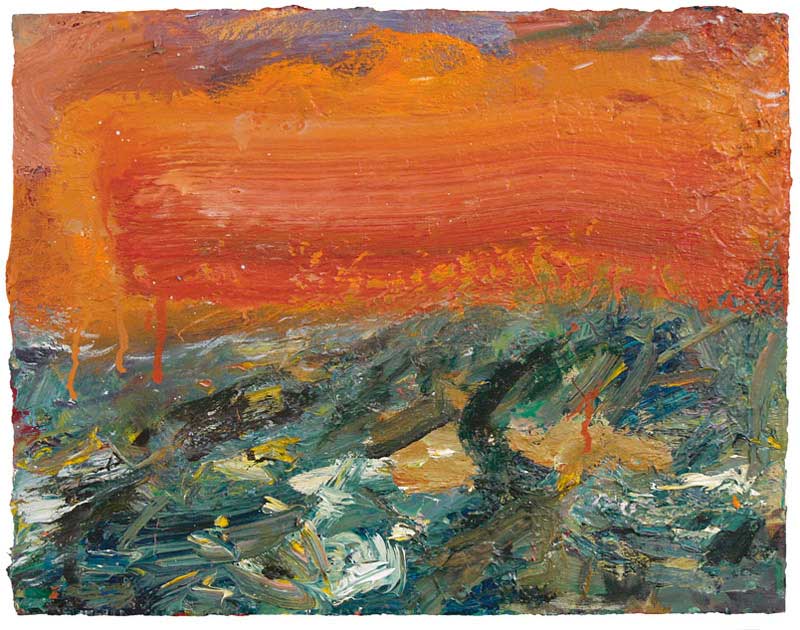

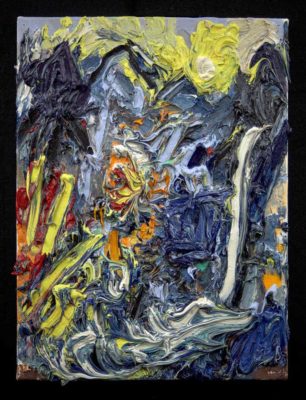

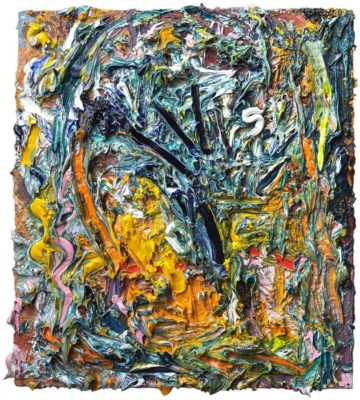

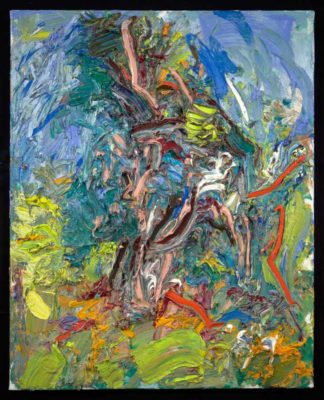

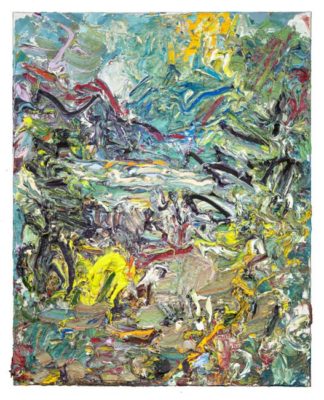

“My goal in painting is to capture nature, in both its toughness and vulnerability, and transmit all of its energy to the canvas. To this end I use intense colors, earthy textures and calligraphic lines, working in the zone where abstraction and representation shade into each other. My interests and training in Chinese painting and calligraphy lead me to a brushwork that is at once free and disciplined.

Color lies at the core of my painting process. I use it to convey mood and memory, and to express a particular sense of place and time. In my painting, color, line and plane interact, pushing each other until they reach a harmony, a unity. Like a jazz musician, I hear the lines of saxophone, bass and drums, each improvising in response to the others, swinging the piece forward. If and when these responses reach their climax, the painting is done.” Ying Li, 2015

LG: Thank you, for agreeing to do this interview, this will be a great opportunity for painters to find out more about you and your fabulous paintings. I’m a big admirer of your paintings and it has been exciting to me to get to spend so much time looking at your work while preparing for this interview.

YL: Thank you for the chance to talk. I’ve read many of the interviews on your site. You interviewed wonderful painters, and many of them I know, they are my friends. You often don’t get to read what painters think about painting, so this is great.

LG: I read that you had first started making pictures as a way to cope with life after you were, in China, forcibly removed from your junior high school to work on a work farm in a rural area during the Chinese culture revolution. This must have been an incredibly difficult time for you, and I was wondering if there’s anything you can tell us about your early experience as a painter and as a teacher in China, that helped shape you today, your work today. Was it reaction to that? Where are you coming from? Please tell us what you can about your past.

YL: Okay. I was born in Beijing, China, the capital of China, a huge city. I see myself as a city girl, maybe that’s part of the reason now I love New York so much. When I was in elementary school, I think I was in second grade, my father was sent to a college in Anhui Province, in the city of Hefei, which is the capital of the province. He was a scholar of Russian literature. When the relationship between China and Russia fell off, these experts were sent to different places in the country. That’s how we ended up in Anhui Province. Then, after that, the Cultural Revolution started and he was arrested one night. We were all sleeping and the people came in and took him away. From that moment on, for ten years, he was in a labor camp. I didn’t see him. He never talked about his experience in the camp, even after he came back home ten years later.

For me, of course it was a huge shock, literally, the next morning, people just stopped talking to you, even looking at you.

LG: Incredible! You’re mother was still there, or?

YL: My dad passed away, my mom is still in Hefei.

LG: I see, I meant were you living with your mother then?

YL: At that time, yeah, but soon after that, I was sent to countryside. This was my first year of junior high. Literally I didn’t have any high school education, because I got sent straight to the countryside to work with the peasants. I was not a rare case. There were so many people, especially in academia and any kind of educational institutions, had background not politically correct. Being sent to work on the farm so young, I lived with a group of students and I was the youngest, I was just lost. At the same time, you had to struggle to make a living, to grow your own food. Right away you had to earn all those credits so you could trade them with food. You really had to work hard.

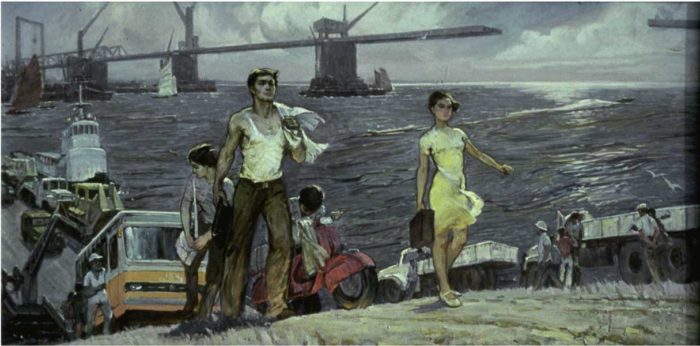

For me, to be with other students, that was life saving. I always liked to draw, to doodle and paint when I was a kid. This was a huge advantage because at that time, they needed people to make propaganda paintings in the village, painting revolutionary slogans, or a simple portrait of peasants, workers, and soldiers, that kind of propaganda work. I got a chance to do those and that was a big break in a miserable life. You got your hands on very limited material you could play with, and then you got a day off from the farm to work on those, that was great when you had a chance like that.

LG: Did you make your own compositions with that or did you have to follow guidelines?

YL: No, they’re totally copied.

LG: Copying from other artworks?

YL: Oh yeah. Totally. There were very strict instructions, exactly what the image should look like. Pretty much, you just blow them up, put it on the wall of official building in the village walls. I worked in the countryside for five and a half years, in two places. I broke my leg at the first place, it was in the mountains where it was very hard to get around if you had physical problems. I couldn’t get any medical treatment, so my leg got worse. Finally, they sent me to another village in a flatter land, that was also closer to the city. However at the time, we couldn’t get anybody in the hospital to get treatment, because the hospitals had closed and the doctors were sent to countryside to get “reeducated” by working with the peasants, during the Barefoot Doctor campaign.

LG: I’ve read about that.

YL: I then got sent back to the city because they just couldn’t take care of the situation with my leg. This was miserable, but at the same time, it was like magic, because in the city I was able to start to get serious about studying art. I found a very good painter, an official painter, who I studied with privately. Basically, I just drew. I drew anatomy; I drew every bone in the book. I drew all those all night long. Then, the schools started to reopen in ’74, I desperately wanted to go to college to study art. But then I found out I was not even qualified to apply because my father’s so called “anti-revolutionary crimes”, background. I was totally desperate and I found where they gave all the tests. I went there and I just drew.

The professor who was conducting the exam didn’t say anything. Later on, he fought for me, to get me into the college. That’s really the first big break I had in my whole life. I was in college. It was just heavenly. Even though our study in art was interrupted by spending so much time doing political stuff, like for a whole semester we went to the factory to work alongside the workers. Then, military training, learn how to shoot, learn how to march. But I just loved being in the college and painting. I couldn’t paint enough. I just wanted to paint.

Thanks to the communist system, if you got into college at that time, the school covered your food and it was free tuition. And, you got some art materials you could use. Thank God I did not paint thickly, like now, otherwise I would have only enough paint for one painting and that’s it! I just painted. I did get criticized for painting too much and for not showing enough responsibility being a politically correct citizen.

LG: Wow, how crazy!

YL: About three years passed, Mao died, and so the whole political situation changed. At that time, I graduated and another miracle happened, they kept me in the college and I started to teach right after I graduated. I was in an art community. At the time you couldn’t just say, “I want to go here, I want to go there.” The government stationed you in the place they wanted you to be. Right away I started teaching in the university, the same department, for 6 years before I came to United States. At that time we did a lot of commission work. The commission work is not like here, you get paid. You’re a government employee, all your work belonged to the party.

Also, at that time, all the artwork would be thoroughly examined by the party. If the work couldn’t pass political inspection, then it could not be accepted and shown.

LG: Did they just judge it by political content, or by aesthetic as well?

YL: Both. Aesthetically it was in a Russian/French academy tradition. It’s very much representational in a totally non-representational way. You had to paint a perfect image if there is a politically correct character in the work. If it’s the enemy, they always looked grey and blue. You can’t make them with red cheeks. There was a code, how to paint certain things.

LG: Right.

YL: In that way, it’s actually very non-representational. We trained in college, in a very academic way, just drew big plaster casts , with hard pencils. At the time, I enjoyed doing that because I was really making things. Also, it’s a very clear and simple thing to do. Either you did it right, or you did it wrong, very clear. Of course, I was not satisfied. I love color, and I love emotional impact, but at that time, there’s no putting yourself there.

LG: Were you ever able to talk with other people in private about your dissatisfaction, or did you just keep your mouth shut?

YL: Basically, I was happy. The fact that I was painting made me very happy. Also, growing up in China you are used to being told what to do. So here, it’s very clear assignment, you do like this, you make it look like that. I was able to do all those and get a kind of satisfaction. Besides those works, in private, we did portraits of friends, and still life. Painted some flowers, landscape. It was a happy time, especially compared with what I went through in the countryside.

LG: Sure.

YL: Also, I was surrounded by people who had similar interests.

LG: You met your husband there, and then you eventually came to the United States, right?

YL: Yeah.

LG: Was it through him that you came to the United States? How did you get here?

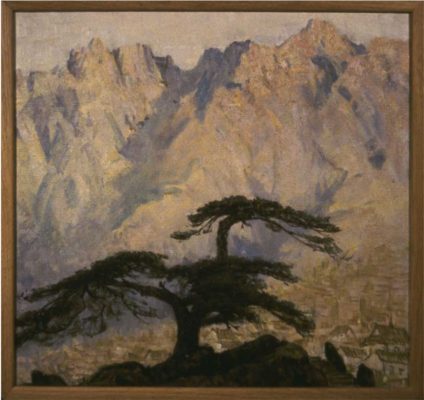

YL: I met my future husband, Michael Gasster, who was a scholar of Modern Chinese History. He was not Chinese. He was a native New Yorker. Had a big nose. Very cool guy. We met on top of Yellow Mountain, where I was painting. It was like magic. At that time, foreigners were not allowed to be in that area. He spoke beautiful Chinese, and somehow, he got around. That’s how we met. We started to write, and then he came back. We couldn’t live together in China, so if we wanted to be together, I had to come to the States. We decided to get married and I started to apply. You have to apply to get married. You had to get permission from your department, from your university, from the Secretary of the party in your school, and from my parents. Can you imagine? I was in my late 20s. Then our case had to go through the foreign affairs office in Beijing, different levels of bureaucracy. We didn’t know if we could get permission, but we got it. That’s how I came to the States.

LG: You then moved to New York and attended Parson’s School of Design for your graduate studies, where you studied with Leland Bell.

YL: I’d like to mention my first impressions of New York City, which was the physical look of the city. I landed in Newark, and we drove towards to the city at sunset. It was like a miracle. I never saw that volume of electricity in my whole life. At that time in China, everything at that hour would just go dark, eight o’clock in the evening. I was like, wow! incredible.

LG: I can imagine.

YL: Also, of course the skyline of the Manhattan. Then the second day, I went to MoMA. That was the first time I got to see Matisse, Picasso, Andre Derain, Giacometti. I didn’t know Giacometti or Derain. I heard the names, I saw reproduction of Picasso, because he was a communist for a short period. China considered him as a friend, so we could see some reproductions.

I saw Bonnard, that first trip, I remember seeing that Cézanne’s The Bather. The single figure, the boy on the beach. My tears just ran down. I read these names in a foreign magazine way back, but to see them for the first time, just wow! It was like a dream come true. That evening we went to the jazz club Sweet Basil, to see Abdullah Ibrahim, a South African jazz pianist.

LG: Previously known as Dollar Brand.

YL: Dollar Brand, you know him!

LG: He’s great, I’ve seen him too.

YL: I remember him playing a piece called African River. Wow. First time I heard that music live. Michael, gave me two tapes after we just met; One of Bill Evans, and the other was Nina Simone. That’s the first time I heard jazz. Then the second day after I arrived in New York, I heard Dollar Brand in person. I thought, “this is a good life.” It’s just amazing.

LG: I can picture your smile then.

YL: Yeah, it’s just incredible. I still remember those moments, so fresh; Maybe that’s why going to museums and seeing these paintings hanging on the wall–for me it’s such a special thing. I had that so late in my life. I didn’t have what is common here,to go to a museum as a student with your art teacher and class. I didn’t have any of that.

Also, another thing I wanted to say was, seeing the de Kooning Retrospective, in the fall of ‘83 at the Whitney. That was the first time I saw de Kooning, I didn’t know who he was. I remember his paintings of women in that show; they had a whole wall of these women. They just knocked me out. How could you paint a person, a woman like that? It was such a door opening. It was like giving you permission.

Also, when you look the painting surface, it was totally different from what I had seen or painted before. When I was in China, I was never satisfied by what I was painting. But I didn’t know what I really wanted to paint like. When I experienced those things, it’s just like, wow, flashing all the time. But very soon after all those excitements I was lost. I didn’t know what to do with my own work. I didn’t know how to paint. It felt like I just didn’t know how to paint anymore. Despite my studying for years and that I had taught for six years before I came here.

I thought I have to study more. We looked at a couple of schools. I liked Parsons right away purely because I could just ride a bike from where we live. We lived in Chelsea. I thought, that’s great–only five minutes to get there and just start painting. Turned out these three professors I studied with, Leland Bell, Paul Resika and John Heliker were so great. They were very different kind of painters with very different personalities. Their concerns in art also very different. I learned from them all.

I think Leland made most impact on me, because he introduced me so much. Friday’s were best, that was when he came in to show slides. It was still slides back then. He brought in the slide box and put in the tray and just projects one after another. From Etruscan sculptures, Fayum portraits, Titian, to Piet Mondrian, André Derain, Courbet and Jean Hélion. Leland was very big on French painting.

He was clear about what he wants, there’s no compromise for him, it’s good or not good. Some people criticize him for that. There is no in between. He really set the bar high. It’s not like you just do what you want. I don’t think he was much interested in seeing or talking about student works. He wanted talk about the great paintings. He was most energized when he was in a museum in front of a painting he loved. he gave you the whole world about the painting. I remember those moments so clearly, when Leland made some comments, it would just click, I knew I was on the right track.

LG: Was it hard to let go of your previous way of doing things?

YL: Not really. I knew I didn’t like what I had been painted. When I came here, I brought very few things with me from the past. I soon started to paint very physically. I painted standing, moving back and forth, a very physical process for me. That’s very different from how it had been in China. I felt liberated Also, I got good response about my work from my professors and classmates. My painting changed naturally and I wanted to keep going. That’s Parson’s.

LG: You primarily paint now from observation outdoors.

YL: Yes.

LG: What keeps you tied to observation? Why not just paint in the studio where there are fewer distractions? Can you explain how your work might change if you didn’t paint something you were looking at?

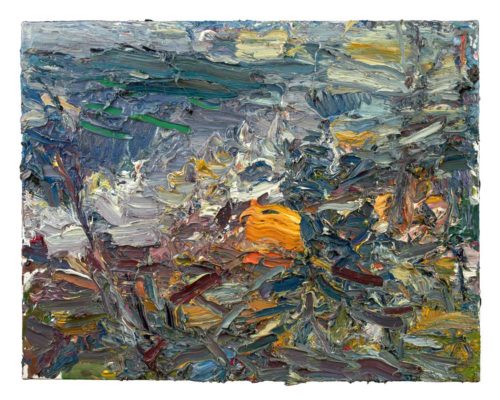

YL: Your relationship with the motif is very different in outdoor painting. When you’re out there and inside of it, you are only a tiny part of your surroundings, that kind of perspective and scale is so different. It’s not like something right in front of you, as in a still life. I like being part of the scene, being there. I love that sensation when I’m out there.

I think my Chinese background kicks in somewhere here. In Chinese philosophy people and nature are one. When you see those classical Chinese landscape paintings there are often a little person somewhere in there, but they are so tiny compared with the huge mountains. A little scholar on a donkey crossing a little bridge with huge chunks of mountains right behind him, things like that.

Also there’s no previously set focus, that is the another important thing. For example if a model posing, he or she usually is your focus. You deal with the relationships of all the other elements with this person. When you’re outside painting it’s like wow! What am I going to do? Where to start? What to choose? Right away you’re just thrown into this chaos and light changes so quickly, you have to make your decision constantly and quick. I love that kind of challenge. I react better and it keeps me on my toes.

I never felt I didn’t know what to do when I’m out there because right away I jump into the painting. In the studio sometimes took me forever to get started. I could just sit there, stuff myself with snacks, listen to music and flip through some art books, but when I’m outside, it’s boom! Right into the game.

YL: I love that feeling. I like the changes and the unexpected distractions, because they keep me alert and sharp. I think of painting landscape similar as the jazz musicians playing together. They make decisions in a split second and improvise instinctively to what the other guys are playing. they listen and react to each other and get things going.

To me, painting landscape outside is a lot like that; it opens doors. I love the change and instability, they help me to make decisions about what’s next. I once painted with Lois Dodd in Vermont. She pulled out this little palette, squeezed little tiny dabs of paint on the palette and then pulled out this little stool and in a few second she started to paint. The sky started to get dark, There was a storm coming. I started to hurry and packing things up…she just sat there and kept painting and then she said to me don’t worry it will pass. It passed. Things like that happen all the time when you’re out there.

These things keep me surprised and make the work more personal and fresh, and not systematized.

LG: That’s a good point. When you’re painting outside is there a balance between what you’re looking at out in nature and then in your painting? Is there a point when you say okay I’ve gotten enough from looking now I need to focus more on the painting? How does that work for you?

YL: I think these two are really one thing; they’re so tied together, looking out and then looking in on the canvas. I try to make that switch as short as possible so I can put down my reaction at that second because that moment quickly goes away and change into my old habits or something else.

Every painting comes out differently. Sometimes I stay in more representational manner because I feel I really got the character or something right there. Or the painting just works. However most times I don’t trust that feeling, I try to get past that point and dig harder into the painting, to find what it is really about. At a certain point the painting gets muddy and flat and I hit a wall. It bounces back instead of going deeper. Sometimes I find I am just repeating my own paintings. I have to paint through those moments, and look harder, I find the solution is always out there, the looking part leads to the clue.

LG: Would you say the looking helps you to get out of yourself more and you become like you said part of nature almost? You know that you’re not so self absorbed and less likely to repeat yourself or use cliché.

YL: Right, and also I find when I work longer in the piece I get less self conscious. So then things start to happen or things become unfamiliar, the painting looks odd and out of control, but that’s kind of a good sign. That means I’m somewhere different.

Philip Guston once said:

“When you’re in the studio painting, there are a lot of people in there with you – your teachers, friends, painters from history, critics… and one by one if you’re really painting, they walk out. And if you’re really painting YOU walk out.”

LG: Frank Auerbach said something similar when he said in an interview “The whole business of painting is very much to do with forgetting oneself and being able to act instinctively.”

YL: Right! Also forgetting what you think nature should look like.

LG: Are you more interested in painting the experience of being in nature over painting a description of what you see? Or is it both? Can you say something more about what that means for you?

YL: I think it’s totally both. The description part of each place totally affects how I see. That’s why my travel to different places is so important for me, when I am in a new environment my perception is sharpened.

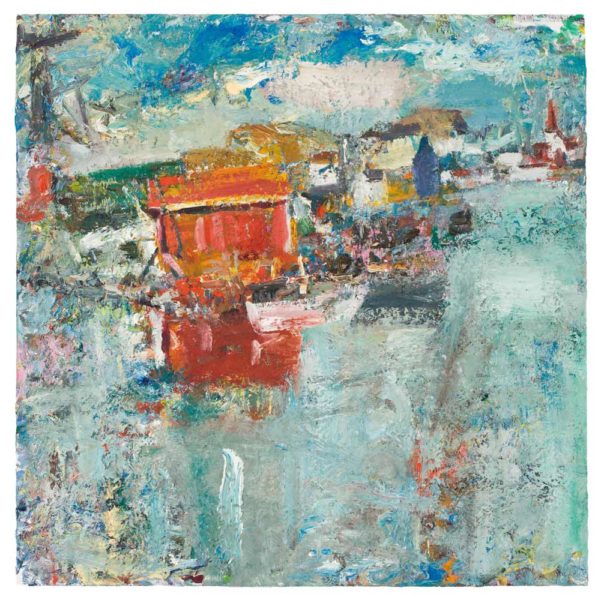

The mountains in Switzerland and Telluride are so different. I think my paintings show those differences. That’s part of being in nature, being in different places. Of course they are two different things. Being in nature, that’s a much bigger framework than just being in the place. Being in nature is like you’re out there. I was talking before about the experience of painting outside and being just a little part of the immensity of nature. Of course being in a different place, your senses react differently.

The description, I don’t quite understand the word description. Okay let’s say we paint what we see. That seeing part is so much to do with one’s mind-state. For example I was in Switzerland two times and in Cranberry Island a few times and the paintings came out totally different each time from the previous times. It’s not like I wanted to do that, they just react so totally different. I saw different things looking at the same piece of water. These two things are so together.

The sensation of being in nature and in that particular environment and time I am painting definitely influence how I see and how I approach to that painting. For example, there is a painting titled “Ascona Valley” in my current show at Haverford College, made in the summer of 2015 under an exceptionally scorching July sun in Ascona. I was painting at the top of the hill and felt the whole valley, including myself, was melting under that heat I was experiencing. That painting is definitely more about the feeling of melting than describing the houses and roads in the valley.

LG: Personality and mood certainly makes for a big difference. You get five painters in front of a scene, even the same five painters two weeks later; they’re all going to be very different paintings. Sometimes painters paint more about what they want the scene to look like than what they see, but everyone’s personality leads them to focus on different aspects of the scene. Painters find what is essential to the scene for them. Clearly your painting of a place will be completely different than Richard Estes, Rackstraw Downes, or Lois Dodd. When you talk about you’re painting your experience of being in nature I just find that so intriguing because so few people say that. They usually talk about responding to what they’re seeing. It’s really more in a way about the experience, your personal experience being there. No one really cares about all the leaves in the try they want to see what is your vision, your feelings, and your summation of the tree as a picture.

YL: Yeah, also I think the description comes in like, let’s say each time you painted the same thing and your focus and thinking are different so what you’re painting there, it’s very different. There’s not just one kind of description, even for the same person. It could be the same day. There’s so much to do with your experience as a person at that time to the place and to what you see.

LG: I recently came across this quote from Jean Hélion that I thought might interest you.

“…a picture can function, can live in itself wherever it has been inspired, whatever may be laterally or accidentally evoked or reminded by it. Painting is a summing-up, has always been a summing-up, of a spirit-activity through sight. Sight taken as a material, as a fact, consistent. Subjects have been borrowed, or followed, or invented, to nourish sight, to develop it, to build it.”

…“Painting makes nature more visible than photography; if representation has been abandoned it is because the proper reality of the picture can develop much further when discharged of the need to represent, because optical reality is an endless field, as endless as nature itself, but directly permeable for intelligence.” Jean Hélion Seurat as a Predecessor in his Double Rhythm, Writings about Painting

LG: Would you be able to say something about how Hélion says painting is a summing up, and it has always been a summing up of a spirit activity through sight. Also that painting makes nature more visible in a way than photography. I’m curious if you had anything to say about that?

YL: The first one the summing up, that is so true. It is accumulation of so many different things, layers of different paintings built up into one painting. I think time and process are everything in painting. They make the summing up possible. The process can be hours, days, months or years, spending on this one piece. That kind of experience is so different from seeing something and then click. That’s a totally different experience. Painting is also a summing up of your history, your understanding about everything, your personality, your handwriting, your touch, and something you saw. A painting you just saw in a museum, might suddenly appears right here in front of you when you are working on your own painting. Or something you didn’t like in your previous paintings, you decide not to go there. All these kind of experience and decision-makings occur during the process, it’s complicated. That’s why talking about paintings is so hard. How this happens is complicated and mysterious. Why not like this instead of that?

Painting makes nature more visible. There are two parts. First of all, physically, painting is related to the physical look of nature. Even the materials we use come straight from earth. That kind of direct connection. Also the surface of painting, it doesn’t matter what kind of surface; there is surface. Take a white painting with no image in it, just white paint, here is a surface painted by a human hand. The painting, in a way, becomes a piece of nature.

LG: That’s why it’s so important for people to go to museums and galleries to see the work for real and not just on their computers.

YL: I know I was just talking to my students about the difference. I had them sign up to do copies and variations of master paintings. One student chose El Greco, first they needed to paint a copy as close to the original as possible It come out didn’t look anything like El Greco. I said to go to PMA, take a look what it looks like, how he painted that, imagine what kind of brush he used, What is the palette? So the student came back and said oh it looked totally different. Of course it looks totally different. The surface. Because painting really becomes an object, It has a life, a life given through the hand of the artist. It is not a 2D flat surface any more.

LG: I’m curious if your approach to painting might have some relation to Taoism, especially with regard to its appreciation of nature and abstract forms of beauty.

YL: I don’t want to just repeat clichés and such about Taoism, but I will say when I think about Taoism I think about jazz. I think about how looking for harmony along with how you try to lose yourself. Sometimes jazz musicians who’ve never played together, perhaps after a band member gets sick and they call in someone new, with no sheet music and maybe even a piece the new musician never played.

You just jump into it to see what will happen, and then you start to make some sense of it, to find harmony with this thing. To me this improvisational flow is like what I’m doing with my painting and I can relate it to the best parts of Taoism. To “go along”, to “just be.” To get loosened up, not be judgmental and enjoy being part of nature.

LG: Does traditional Chinese calligraphy influence your painting?

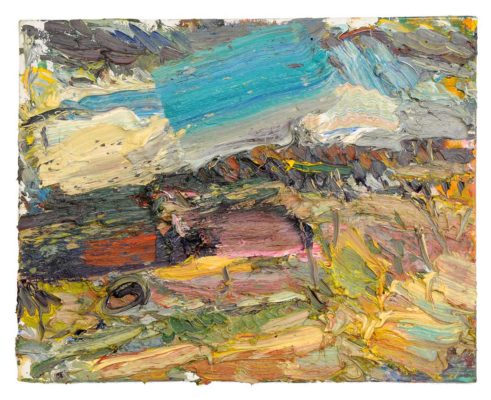

YL: Totally. That’s a major thing I’m looking and thinking about now. I started studying Chinese calligraphy in the first grade, I think it was even before the first grade because in China at that time, your calligraphy shows if a child is educated or not. It’s part of who you are. My parents were very encouraging with calligraphy and the arts. I remember our apartment back then there wasn’t a particular space I could do that so in the summertime they set up a little table and chair along with the paper and ink and I would sit under a tree and just practice calligraphy. I loved it. Later I studied Chinese calligraphy and painting in college where it was part of the requirements along with Western painting.

At that time in college I was bored because the calligraphy teacher, who was in his seventies at the time, with yellow fingers and teeth from smoking his whole life, he also smelled really bad. He would ask us to do the same stroke, over and over, for the entire class, the same stroke, nothing else. The whole semester with just making different strokes and dots. I tried to escape this class as much as I could. I thought, “This is so boring, it’s like painting with soy sauce.” At that time I wanted to express myself more with color.

But now, thinking back, it was very important to me, for how I paint these days. In Chinese painting, every line you put down, how you start and end a line; it has its own eternity. It is complete. It’s not just busily filling the canvas, brushing on the paint. Each stroke emphasizes meaning, poetry and expression.

I also studied with an old Chinese calligraphy master after I came to the United States. People would bring him old paintings and calligraphy for him to evaluate, to see if the work was a fake or not. He was a real authority on that. He would sit there and say “Ah, open!” The Chinese paintings, either hanging or hand scroll, would only begin to be unrolled, when he would say “Stop, it’s real.”

The person would ask “What are you talking about? You haven’t seen the thing.”

He said, “I don’t need to see the whole thing, I’ve seen the hands.” Just like that. He was right. It’s amazing, how much the lines tell you about the hand, the touch. There’s so much in those lines. So to me, more and more I think about that. When I paint, it’s not just from the wrists and fingers, it’s your entire body. Sometimes when I can feel a painting isn’t going right, it’s like my whole body feels awkward.

Calligraphy is so important. And I probably wouldn’t say this ten years ago, because I was too shy to say that. I was told not to think about the brushwork or the surface when I was painting. Instead I should concentrate on the forms, on the color relationship, the formal concerns. Get the structure right. But now I also think about how the paint is put down.

LG: With your setup, do you work with the canvas vertically or do you have it lying flat? I ask because I am imagining calligraphy as being done with the paper or the support lying flat.

YL: Sometimes I do just put it on the ground, and start to do things and put it back and take it down. I do a lot of these and switch around. I work with it on an easel, a Stanrite tripod easel. I never use French easel because they’re so clumsy and heavy, I’m always having trouble with those legs. I accidentally kick it and something collapses. Also you can’t easily carry big tubes of paint with those. I love how the tripod easels are so sturdy. But it’s very hard to find this model of the Stanrite easel now. I also have a backpack to carry my big tubes of paint and supplies.

LG: That makes a lot of sense. Please tell us about how you go about starting a painting?

YL: I don’t start a painting using any particular system; they all start differently. Usually something hits me, like how the light or something gives me an idea for the structure or the motif. I might find one thing in front of me that I’ll respond to, put something down to just get started. I paint directly on the canvas, I don’t make sketches or draw beforehand at all. I do try to be very faithful to what I’m looking at right at the beginning; but the number one concern is the structure. Try to get the structure for the painting to feel right.

The initial idea always changes. Once the paint gets on the canvas I am also responding to the paint as well as what I am painting. I use different kind of brushes, or whatever I can grab. This also can totally change the feeling of the structure. After getting into the painting I start to see different things and problems. The painting feeds you with all these problems, so you have to quickly make decisions, just a few minutes can take you somewhere else. I make a lot changes during the process, keep things open.

LG: When you start painting do you use a very thin, wash or do you just go right in with a loaded brush, use lots of paint? Or is each painting different?

YL: With paint, I try to keep my materials as simple as possible. I use a classical medium. Paint thinner, stand oil and linseed oil. Actually I use very little medium now. I try to keep the material simple because I paint so thickly. I don’t want to have any complications. Straight paint is the best solution.

LG: What kind of paint do you use?

YL: I use whatever on sale.

LG: Painting thickly like you do would certainly make the expense an important concern.

YL: Whenever I sell a painting the first thing I buy is a bunch of paint. I use paints like Utrecht, Gamblin, also Lukas. I like them for certain purpose. Lukas is thinner and more fluid, which helps when I sometimes draw with squeezing the tube of paint right on the canvas. I use Winsor & Newton. I always buy the big sized tubes. I used to use Williamsburg when Carl Plansky was still around, he would give me a big discount but you can’t get it now. No more.

LG: Williamsburg’s pretty expensive for the large tubes.

YL: I know! And their small tubes are like one squeeze and that’s it! Once a while I indulge myself with the Old Holland. But I’m often reluctant to use such expensive paints. More often than not they just stay there in my bag and I go straight back to my Utrecht.

LG: I can relate. I once heard someone say, that with students it’s very important to use as good and expensive paint as you can afford to buy. But when you’re a master, you use the cheapest paint you can get because you know what to do with it; you know enough about its properties to be able to use it effectively. Handle its weaknesses and strengths, like with tinting strength. A master knows how to make good color regardless.

YL: You know Lennart Anderson used Utrecht. I saw him painting at Montecastello, in his bags all these Utrecht tubes. I said “Leonard, you use Utrecht?” “Why not,” he said, “it’s good paint.”

LG: I think Stuart Shils also uses whatever finds that’s affordable and decent. Of course many abstract expressionists like de Kooning used house paint.

YL: I also try all different brands. I’m so not-fussy about paint.

LG: Your paintings, they’re usually done alla prima? All in one session or do you work over multiple sessions?

YL: I work both ways. Some finished in one session and for some I’ll go back to the same spot, paint over multiple sessions and also I keep working on them in my studio. Sometime I’ll change it into a totally different thing if it just didn’t work out. But painting from looking always plays a huge part.

LG: How important is privacy for you, when you’re painting outdoors? Are you able to ignore onlookers, so they don’t influence your work? I know for me, if I’m out painting and someone is watching me, it often messes with my head and I don’t as free to paint or experiment out of the fear of being judged or something. Do you ever feel like that? Especially when painting with a more abstract orientation.

YL: Not really. I can shut people off when I am painting. A few days ago we had open session at the school and I drew with students, for three hours I didn’t say a thing. At the end, a student said “Are you OK? Are you OK?” I replied “When I’m working, I like to be left alone.” It’s not therapy.

When I’m out there, I don’t mind onlookers. The privacy really is not issue for me. I guess because I grew up in a place where there’s no privacy, not even at work. I can ignore whatever. When people try to make conversation I just said “I’m working.” Or I just don’t respond. And they look at me and say “What a crazy person.”

LG: That’s a good defense. You’ve talked a lot about jazz. Do you listen to music when you’re painting? Or would that interfere with the musicality of your own painting?

YL: Yeah. Music is a tricky thing. I listen to music in my studio before I start, sort of a transition, put me in the right place mentally. Separate from whatever before. Music’s so seductive. I find that if I paint while listening to music the painting can start to look better than what it actually is. Sometimes I turn on music, perhaps a Beethoven string quartet and emotionally you’re so involved, the painting seems amazing. But then the next day, I’ll look the painting and wonder what was I thinking, it’s so flat! Music is a tricky thing. All kinds of sentimental ideas kick in, and you start to see things that aren’t there. Also, when I’m outside I never listen to music because I love hearing the sounds around me, they are a part of the whole experience; an important part of what that painting is about.

LG: That’s a great way of thinking about it.

John Thornton's Video of Curtis Cacioppo performing Synaesthesis, a tribute to Ying Li's paintings.

LG: There is a US premiere of the composer Curtis Cacioppo new piano sonata, which is inspired by your artwork, to be performed September 21. There’s also a video made by John Thornton, which is made along with your artwork. I was hoping you could tell us a little more about this.

YL: Curt Cacioppo is a composer and music professor at Haverford College, he teaches composition and piano. He himself is a fabulous pianist, and his music is very much grounded in the classical Western music, but at the same time, all different kinds of things going on there, very contemporary, but at the same time, you feel the foundation there. Sort of like, the kind of a painting I like, you know?

I always love his music, and he likes my work very much. then we did collaborative work. I did a bunch of CD covers for him. He composed this piece titled Synaesthesis literally looking at a video of my paintings he called the interior of my paintings. The images in the video are close-ups of the surface of my paintings, they look like valleys and little caves make of paint.

LG: Interesting.

YL: Yeah, just sort of like you’re travel in it. Also, this piece, this video shows some our collaboration. I was painting, and he was playing the music, and I was drawing him. One drawing will be in this show. It’s a sketch of him playing piano. I thought it was pretty good. Looked just like him.

LG: Have you been back to China since you moved here? Have you ever gone there to paint?

YL: Yeah. Not that regular. My mother’s still there, and of course I love to see her, to see my friends, but I rather go to Europe to paint. I somehow, I just cannot paint in China. I guess there’s too much baggage on my shoulders.

LG: Is there many people doing landscape painting there now? Like contemporary outdoor painting?

YL: I don’t really follow it. I mean, I feel like I’m so removed from it. I do see landscape paintings. Also, the Chinese painters, their landscape paintings, it’s very different from what the classical Chinese paintings are, but at the same time, the elements is still there, the brushwork and the control. The control is such a big part in Chinese painting and calligraphy, but at the same time, how to free yourself from that. I’ve always been interested in that kind of process and evolution. Being very controlled in a limited, narrow window and then how you can come out of that. Quite amazing.

LG: Did you see the Frank Auerbach show? In London?

YL: Yes, I did! For a period, when I was at Parsons, his paintings were very inspiring. I was obsessed with his work and Giacometti, however now, his work feels more remote to me.

I haven’t look at his work for quite a long time, but I did see this show. To me, he is a great painter, his devotion, his obsession, and his single-mindedness. There are many paintings in this show are very powerful. However I’m not as crazy about his landscapes. I think these portraits, those heads, they’re incredibly powerful. They’re transformative. there’s so much about what being a human is about.

Those early work, I thought they are just great. They’re very powerful. They’re so packed with emotion, physicality and the struggle.

Leon Kossoff is another one. In a way, I feel Leon Kossoff’s work is even more personal. I feel like he’s more connected with his motif.

LG: I would think Stanley Lewis would be somebody who you might feel connected to.

YL: Oh yes! We are great friends. I have so much respect to his work and to him, as a painter and a person. He is a great person to be around. We taught at Chautauqua Institute at the same time and I saw the way he worked. I thought, I paint pretty hard, I work hard, but when you see him, it’s, oh, I’m immature.

LG: Oh no. Why, what does he do that’s so different?

YL: It’s not so much that it’s different. It’s more about his intensity and focus. Every morning, he gets up at 5:00. Then he just stuffs some cereal in his mouth then just disappeared right down to the basement, where his studio was. Then he started to work, He sits in a little shed he built himself. Actually, he offered to teach me how to build the shed so I can carry around wherever I go to paint. Then he’d just sit there, on a stool with his canvas right there, and his little tiny brushes, he just goes on painting for hours, hours, and hours. Then, in the evening, I think he was just so exhausted that he fell asleep on the rocking chair, like at 7:30 or 8:00.

LG: Amazing.

YL: The next day he gets up at the same time and does the same thing, next day, same thing. Seeing that dedication and intensity is so inspiring.

LG: Well, your work is very inspiring to me to look at, and hearing you talk as well. Congratulations on your show…and thank you again for doing this interview, and it was a real pleasure and honor to have the chance to talk with you.

YL: Thank you.

YL: I’m going back to Telluride, Colorado this, actually, in couple of weeks. I will be teaching a workshop, and I love that place. It’s just great for painting, and I love people there. Last fall I was there, I had a great time. Some of the paintings I did there are in this show at Haverford. I teach a workshop and also paint. Also, I would love to go back to Rome. My dream, the current dream will be stay in Rome for at least a month, just paint on the street, you know? See what happen.

LG: Maybe you’ll paint in the forum there. Would that interest you? In the ruins?

YL: I can paint anything. I had this moment yesterday where I walked out of my office and there was a bunch of cars next to the most boring looking building in the whole world, then there were these giant old trees back there. Somehow, just for a moment, I started to see a painting. I thought, “Oh. I could just paint it right here,” you know? It really doesn’t matter.

LG: Do you live in New York, or in Pennsylvania?

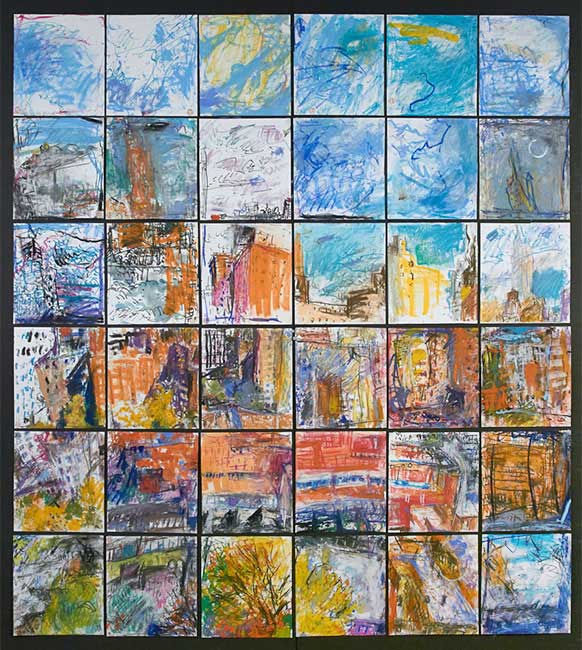

YL: I’m in my office at Haverford College in Pennsylvania. When I’m not teaching here, I go back to Manhatten. Also I’ve been working on these cityscapes from Michael’s window.

click link to view or purchase the blurb book – Ying Li: From Michael’s Window by Ying Li

LG: It was a very impressive display to see all of that. That must have been a very important piece for you to work through all of this after your husband’s passing.

YL: It’s just so awful. Painting in his study really helped me to get going, keep going.. I have so many paintings I want to do from that window.

Streaming version

John Thornton's Video on Ying Li

A wonderful Painter and person. Ying is inspiring, her sense of who she is reflected through her paint. Truly authentic painting.Truly beautiful painting! Thank you for this interview.

Wow! What terrific painting -lots of zap! – and what a terrific interview. Thanks for this, Larry. And thanks for the hard work you put into this site.

Powerful paintings! Wonderfully articulate and substantial interview and video.

Wonderfully dynamic paintings. I really enjoyed reading this interview and look forward to listening to the audio podcast in my studio tomorrow. Many thanks to the both of you