Martha Armstrong was in San Diego a few weeks ago and agreed to an interview with me. We met at a mutual friend’s home where we sat out on a hillside deck overlooking a huge valley with the distant city and ocean beyond. We talked at length about her history, painting process and thoughts on art, occasionally interrupted by roaming peacocks looking for handouts.

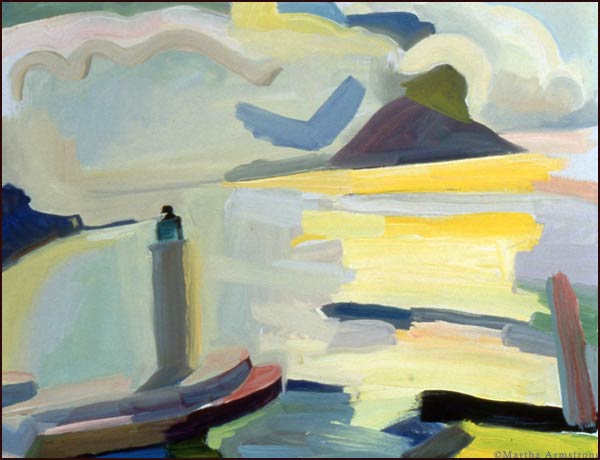

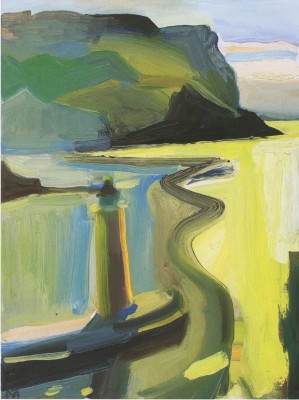

I’m keenly interested in Martha Armstrong’s paintings especially as a means to further explore the range of possibilities for painters to use observed nature as either as a point of departure or as a reason in and of itself. Martha Armstrong’s painting combines close observation with invention in a balanced measure, which she uses to create solid structures and harmonies that dance parallel alongside nature. Armstrong takes the most interesting aspects of what past artists have explored in this realm of abstracted observation–Bonnard, Braque, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keefe, Lois Dodd among others–and makes it a uniquely personal and inventive manner of responding pictorially to nature.

The New York Times’ Roberta Smith reviewed Martha Armstrong’s Bowery show, Martha Armstrong’s Nature Scenes at Bowery Gallery, in Sept. 24, 2015 saying:

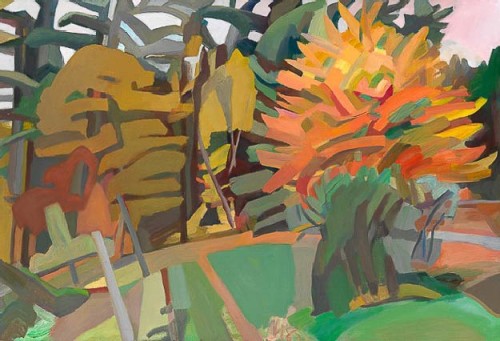

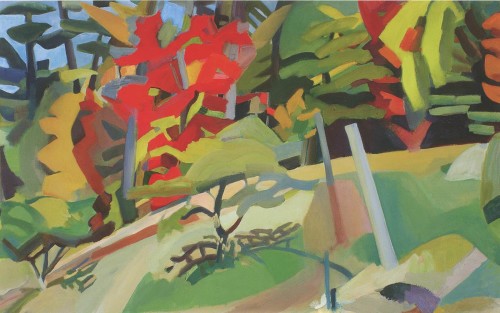

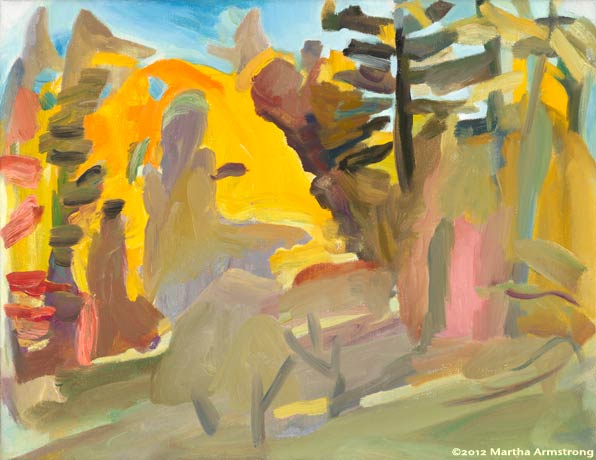

“… Ms. Armstrong is the suave disciplinarian of a muscular style. She stacks blocky shapes of color that describe one landscape — a hill with some woods and a shack — visible from the window of her Vermont studio that may be her Mont Sainte-Victoire. But her shapes also maintain a nearly sculptural independence, hovering slightly above the image, just beyond legibility. At once improvisational and carefully carpentered, these paintings explode toward the eye, like nature on first sight, at it’s most welcoming and irrepressible.”

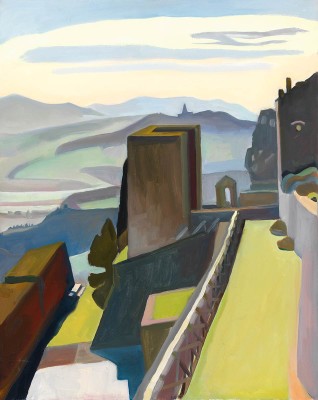

Martha Armstrong is conducting an early June residency workshop in Italy at the International Center for the Arts at MonteCastello di Vibio. See this link for more information.

Below the end of interview I’ve included quotes of paint-wisdom from her previous writings, these gems read like art-koans. I’d like to thank Martha Armstrong for being so generous with her time and attention with making this such a thoughtful interview.

At the end of our interview I’ve included quotes of paint-wisdom from her previous writings. These gems read like art-koans. I’d like to thank Martha Armstrong for being so generous with her time and attention with making this such a thoughtful interview.

Martha Armstrong is represented by the Elder Gallery, Charlotte, North Carolina; Oxbow Gallery, Northampton, Massachusetts, Gross McCleaf Gallery Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the Bowery Gallery, New York City.

From Armstrong’s website:

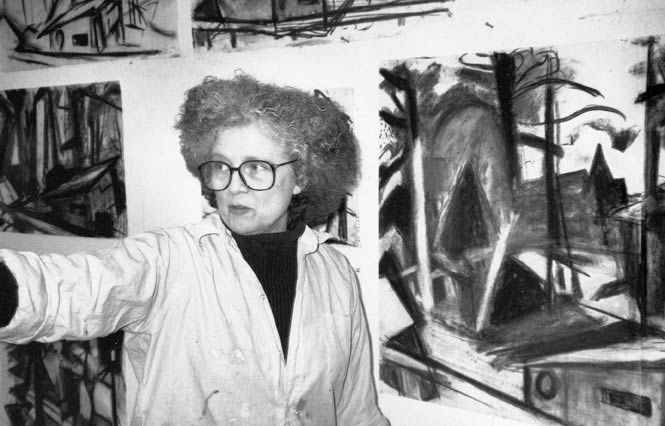

Martha Armstrong has had many one -person and group shows in the United States and Italy. She has received grants from Smith College, a residency at Hollins University, and at the Camargo Foundation in France, and was a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome.

She has taught at the Kansas City Art Institute, Indiana University, Smith, Mount Holyoke, Dartmouth, and Havorford Colleges, and now is a graduate critic at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

In 2003 Alexi Worth wrote in The New Yorker, “Armstrong’s high, sharp energy is Yankee Fauvism at it’s best.” Lance Esplund, in Art in America, wrote in 2004, “I enjoy the all-out belting of the melody which is full of honesty and heart.” In 2009 Victoria Donohue wrote in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “In these works it’s still possible to believe that aesthetic presence might have some impact on the hard reality of everyday existence”, and in 2011 she wrote: “Her landscapes have a simplify and power; Their intensity of focus on feeling and seasonal changes (are) ambitious exercises in reconciling geometry and gesture…”

Armstrong studied at the Cincinnati Art Academy, Smith College, and Rhode Island School of Design. In addition to Bowery Gallery she shows at Gross McCleaf Gallery in Philadelphia, Elder Gallery in Charlotte NC, and Oxbow Gallery in Northampton, MA.

Larry Groff: How did you become a painter? Was there a lesson you learned that was most important in shaping you to be the painter you are today?

Martha Armstrong: This is an easy question because I remember thinking of myself as a painter in grade school. I remember a teacher in kindergarten who could never get me to put the paintbrush down. I loved painting then but of course “art” was pasting cotton balls on paper plates.

The great teacher in my life was Anneliese von Oettingen who came from Germany after World War II to teach ballet. She taught me what art is. She had been the ballet mistress of the Kurtfurstendamm Children’s Theater in Berlin. She was demanding, loved dance—it was the most exciting thing to do. She taught what form was and what rhythm was. I had such a feeling from her about what art was and the discipline needed to get there. I always considered her the best teacher I ever had, an amazing person.

LG: You later went to art school, this was early on?

MA: I went to The Cincinnati Art Academy in seventh and eighth grade with friends. We found it kind of a lark, it was part of the Museum. We could always go over there to look at paintings. There were serious classes in perspective, and eventually life drawing and still life painting. We had a wonderful time. I look back on that as some of the best training I had. These were art students teaching classes to kids, and they were good. Later, one summer while in college, I studied landscape painting with Julian Stanczyk who had been a Polish refugee via Africa. He made a comment that after his experiences in Poland in World War II, he could never paint anything figurative. The physical world was just out of the question for him. He had gone to Yale and was an Opt artist. He shows at Danese Gallery in New York. He was a great teacher, a humanist in a way. He got me to read John Marin’s letters, directed me to look at certain artists.

LG: Is painting from observation central to your process?

MA: I certainly start with something or someone I’m looking at, and often I’ll go from beginning to end just looking at each subject. But my whole motive will be to get what I see, and determine how to translate that into painting. That is the first question. How do you put that down? How do you make sense out of that visually in paint?

It’s the most exciting thing in the world to do—to look and paint. But I don’t know if I end up there. I will take something back to my studio, and continue to work on it. However, the issues are completely different then. When I’m teaching outside and have someone look at something and the student eliminates this and that I’ll ask, “Wait a minute. What are you painting here?” They’ll say, “Well, I didn’t like that tree or, you know, I can’t paint cars so I left the car out.” But that’s just jeopardizing the whole purpose of what you’re trying to do, learning to look at something and put it down.

If you’re out painting a landscape you try to deal with what’s there. Take it into your studio and it’s a different story. You have to make a painting out of it. I get curious and try things, try to paint things several different ways- often destructively. You have to do what you have to do to make a painting. I can always take it back out again too, which I often do. It has to recreate my experience of looking at something, and I think the older I get the more complicated the world seems. I don’t want simple answers. I just want it to be truthful to how I see the world now and to get a painting at the same time, and that’s hard.

For me it’s very important to stay with the subject and deal with what’s there. If I’m painting outside, that’s what I want to deal with. That’s half the fun. I don’t feel I can leave things out; that’s lying. I have to stay with it as long as I’m painting outside. I think Suzanne Valadon is a compelling painter because she didn’t lie in her work—she told lots of lies about her life. In her work she was straight, honest. Her paintings can seem awkward but you trust them.

I make studies from life because the light changes so rapidly. To get it you have to paint with all your concentration to get an equivalent, go through the subject from beginning to end. It’s like playing a piece of music. You ask how does this relate to this, and how does your eye move in the landscape?

Now you can make corrections and changes as a painter. A performer can’t do that in music, but it’s trying to make everything connect the way you play a piece of music. It’s linear in time but it’s not linear like music. It’s all over the place.

LG: Is thinking while painting something you welcome or avoid? Why?

MA: Thinking is a curious thing. If I’m out just looking at something and trying to paint it I’m hell-bent to get what I’m looking at, and my thinking is focusing on that. It is a kind of discipline to stay with it until you’ve tried to see yourself through something. I’ve painted a lot of small paintings that way. Big paintings as well but they’re a different problem.

Mostly I try to get everything out of my mind. I don’t want to think. You need to get away from all your critics and get away from all your demons. I don’t want to think about them. I don’t want that to be part of the present. I want to be as free and open as I possibly can. Often I’ll put on the radio to distract me. I don’t need to listen to it; it’s just enough of a distraction that I have to concentrate on what I’m doing.

I put music on too but music is so demanding that I find it hard to paint. You’re entitled to do anything to keep your energy up. I’ve put on opera very loud to force myself to concentrate.

LG: Do you ever find that music can give you a false sense of how the painting is going? Like if the music is really upbeat and makes you feel good and then you also feel good about your painting but interferes with you from seeing the work?

MA: I agree with you. It has nothing to do with the painting. I think that’s an issue. I think it just makes me concentrate on the music and not the painting, and so I find that a distraction.

LG: But music could also be a good thing if it helps get rid of other distracting demons, or other thoughts that would kind of mess with your painting concentration.

MA: Right. You can’t get at your intuitions if you’re too focused consciously on what you’re doing. I’m an intuitive painter. I think that it’s very important for me to get beyond conscious thinking so that I can just paint. Intuition is really the right word. I can’t … I know that that’s where I want to go in my head when I’m working. I don’t want to figure everything out logically. The only thing that gets you there is working.

LG: Some people feel that when you “get into the zone”, or however you phrase it, this is where you let go and start working on as intuitively, that’s where the best painting happens–when you’re on automatic pilot and not even aware of time going by.

MA: Absolutely.

LG: It can be like, “Who made this?”

MA: True! Afterward I sometimes have no memory of doing it. I won’t necessarily think it’s a good painting. In fact I might think, “Well, that’s not what I was after.” A year later I’ll think, “My gosh, that’s a really good painting. Why didn’t I see it?” I don’t remember doing it. But I can be miserable and feel desperately self-conscious and hopeless—and do a good painting.

LG: I think that’s one of the most interesting things about working from life. Many people don’t get the appeal of being outside and dealing with the struggle of working from observation. For me it’s harder to lose your self-consciousness and to get in that space unless you’re reacting against something outside of yourself. Of course you can still get at it working from your imagination and other more internal means but it’s from a different angle.

MA: Absolutely. That’s wonderfully put. I agree with that.

LG: What artists are you most interested in having a conversation with in your paintings? What sorts of things might you want to talk about?

MA: When I’m working I want to get at my own work. I think it’s really what any artist has to do. I don’t want to think about other painters while I’m working. Philip Guston once said, “You’ve got to get everyone out of the room when you’re painting, and then you have to get yourself out of the room.” That’s very well said.

It’s interesting that, as a painter, you can have friends 400 years old who you feel very close to and with whom you have conversations so easily; but not while I’m painting. Something might flash into my head, but I certainly don’t want my painting to look like someone else’s paintings, because then –that’s not my work.

LG: How about conversations when you’re not painting?

MA: Oh, yes. Endless conversations. I mean, it could be Matisse, or Kandinsky, Manet, or it could also be things … I love trees and like to identify them, I studied botany. When we are in Vermont there are so many different mushrooms with such beautiful colors. You can line up 6 gray mushrooms but every one is a different color, they’re amazing. I have conversations with many different painters but also with things, about what things look like, how they’re constructed.

LG: Your use of color to give the feeling of light is astounding. Please tell us something about your concerns in translating your response to light into paint?

MA: It does seem to be translating light into color, but color is the substance of painting. You don’t have actually a light in there, a light bulb, so how do you translate that? I think a lot about translating light into color, but you have to structure the painting at the same time. Maybe it isn’t tied to the physical structure that’s out there; maybe it’s tied to the painting structure, which might not be the structure you see. It’s really both, in terms of the painting. I want to create a light in the painting.

One painter I’ve always loved is Pieter de Hooch. He is an odd painter from the 17th c. His color feels very modern to me, compared to Vermeer and other contemporaries. You see this in how he plays this red against that red, or how he’ll use blues in the sky in relation to these reds; his paintings are really built on color. You forget the subject. They’re abstract. I remember going through the Louvre once, you get these little rooms that are floor to ceiling paintings, and I was looking around and all of a sudden there was a wall that just seemed lit up, it was a group of Pieter de Hooch’s paintings–surrounded by other Dutch painters of the same period. The color was working as a light in his paintings in a way that made them stand out from the others. Compare Velasquez to Zurbaran: Velázquez was a tonal painter, and yet Zurbarán’s color, to me, is so emotional. I just look at it and feel like I’ve been hit over the head.

I spent a long time making collages, like Ken Kewley does. I mean doing collages, collecting lots of paper that I collected from everywhere. Things like cigarette wrappers I’d find in the street. I’d pick up anything, pieces of metal, photographs, and other stuff I might run across and by making these collages I could see how the colors work together, to make a structure. Some of my collages are figurative, others are abstract. Gross McCleaf showed a whole bunch of them about a year ago. Making them years ago really taught me a lot about color. It’s a very specific way of learning about color because you can change the composition over and over until it is clear, then glue it down.

A lot of my teachers wanted us to paint abstractly. “Why don’t you paint a lemon, it’s going to be a lemon anyway, if you have to paint representationally.” That’s a quote from a teacher. “If you have to paint representational, at least try to make it interesting.” That’s another quote. People believed pure abstraction was going to be here for a thousand years. I think there are a lot of painters my generation who loved abstraction, but I loved to look at the visual world and to paint the visual world, so, I found that idea too limiting—to eliminate the subject. All painting is abstract anyway.

LG: When you paint a scene like what is in front of us now, a huge vista with trees and bushes in the foreground out here, I somehow don’t see you painting it with same naturalistic greens that we see. I imagine you would find an equivalent, to transpose what you’re seeing. Do you look for something similar in value, saturation or feeling perhaps? I’m curious how that works for you.

MA: I think my choices come from doing collages. If you get too many different colors together, they start cancelling each other out. Matisse would start a painting with 3 colors, he’d often put on 3, like a touch of this, a touch of this, a touch of this. What are they doing for each other? I don’t do that, but I know you can’t make a color statement out of too many pieces of color. You’ve got to focus on what this does compared to what that does. Grays become extremely important to make these colors sing, because the grays aren’t going to take over the color or alter the color, they’re going to give them space to breath.

Looking out at this landscape I see beautiful bluish-greenish grays, and that’s where I’d start, trying to figure out which real pieces of color I could use to set up that kind of harmony. It would have to be a learning process of what do I really need? What statement in blue is going to go with this statement of sort of a greenish-gray that’s going to give you something equivalent? Paintings are metaphors; you’re not looking for a copy. You’re looking for a translation. A copy doesn’t do it. You can take a photograph, and this is the thing that a painter has that a photographer doesn’t have. A photographer’s got to deal with it all, and choose how close, how far, and what kind of focus. Painters have the ability to say, “Okay, I need this and that, but if something doesn’t work, I take it out.” (I don’t think this is a contradiction about dealing with the whole subject!) I might start with too many colors– it would be a process of synthesizing to get what I need. I am wary of things becoming decorative; colors should say something, not match.

LG: That color translation of the observed world is a big part of what gives painting it’s power and poetry. Painters who copy photos can often miss this.

MA: Photographs are extremely seductive for painters. Can you imagine when photography first came along and painters were looking at an image and thinking, “My god, I just spent 3 weeks on this hand and this photograph got it in seconds!” I think it led to Cubism. I think Cubism came from artists saying, “This is how I see it, not the camera.” It’s very natural to painting; the motive isn’t to get a representation but to bear witness to seeing. Photography can be seductive. Photographs are not paintings.

LG: Is there a point in your painting when you respond more to the painting’s needs and less to the observation? You said you often work on the painting in the studio after you’ve been working on it outside.

MA: Dichotomy always seems to be the word that describes painting best for me. There is the 3-dimensional world that your are trying to put down in a 2 D flat space. There are periods in painting that seem to me to represent that idea like Early Renaissance paintings, when painters still had a foot in the Middle Ages, all those bright colors and various conventions and kinds of abstract devices that were used for painting. Then you have people wanting to represent the world the way they think it looks—which changes from period to period. In the High Renaissance artists looked to the Romans (and Greeks). In the work of Michelangelo and Raphel and Leonardo painting feels seamlessly in one world. But those earlier painters, like Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Benozzo Gozzoli, Pierro della Francesco who have strange bright colors, and they have these little constructed narratives going on, it’s a dichotomy of two different worlds at once.

I think Cubism is also a dichotomy between the physical world and the artist’s take on it. It doesn’t get completely abstract and it’s not completely representational. The observed world is a vehicle; the painting has its other demands-two different things you have to juxtapose.

LG: What are some thoughts you have about deciding on the underlying structure of your painting? Is this something you study before starting or does it come after you’re underway–out of the paint?

MA: When I was young with little kids and was out painting, I would often take a scrap of canvas because I didn’t have time for stretching one. I would chastise myself thinking, ” You should be more disciplined. You should get up earlier in the morning to stretch the canvas, etc.”

However, I soon realized it was a tremendous experience to paint on a completely random piece of canvas because I had to build the image from the inside. I couldn’t lean things up against the edge like, “Oh, you’ve got this line and this line and this line, these are lines on the painting.” I don’t have those. You have to build the painting and then decide what the edges are.

In Vermont I used to have a huge piece of plywood, 4 by 8 foot, and I’d tack a canvas to it because there was so much wind up on our hill that it was very hard to hang on to a canvas. I never knew quite where it was going to end … They could be big paintings, sometimes 48” by 60” or something like that, or almost square, 48” x 49”.

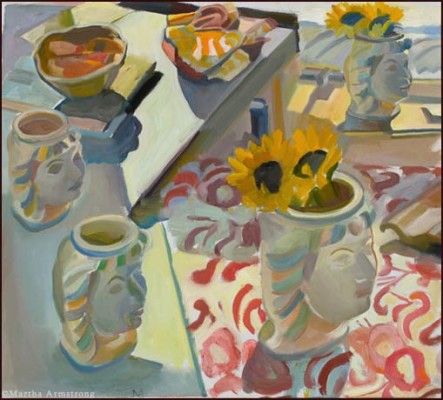

I have some still lifes all done on pieces of canvas where the light first comes in on the left and I start work at the edge and then the light is moving and it’s picking up the same bowl or orange. This is the last piece of it on the right. The painting is put together from 3 different takes on the same still life. This bowl is this bowl, the light has moved over there to the right. Nobody gets that when they look at the painting. It isn’t obvious that’s what’s going on—but I’ve painted the same still life 2 or 3 times in the same painting.

The light in an hour is changing every 10 minutes completely. You’d paint it once and then you’d paint it again and then you’d paint it a third time. (See Triple Valentine) That might be the end of the painting.

LG: You thought of that beforehand or this sort of occurred to you as you go on, “Oh I can just move with the light?”

MA: It happened, I didn’t plan it, but it came easily from painting on scraps. I got into doing a whole lot of paintings that way. It’s in our kitchen in Massachusetts. I would see this and think, “I have to paint that.” It was on the breakfast table. Then the light would be over here, “I have to paint it again.” Then to start connecting them in the same painting was what happened. It’s just sort of experiential. You’re looking and you keep on looking. I’m following the light rather than the subject.

LG: Then later you would go back and perhaps unify it more or eliminate something that didn’t quite work right?

MA: Yes. Okay, I’m going to put things in that are not in the light and develop them after the light’s gone. I probably made a note of them. These things all were noted in here right away. Then you’d have to decide how to make a rectangle out of it. Sometimes I have to add something because I have a hole. See Venus of Sicily below. The vase is a folk art vase from Sicily. It wasn’t in the painting but I needed something in the lower right corner. First I tried orange sections, which didn’t work. Then I chose the vase and did a series of practice heads.

At first they were just little paintings. I did them to warm up before I went to work on a landscape that I probably had out in my studio that I couldn’t take back to Vermont because of the snow on the ground. I thought it was really interesting because I realized it had a lot to do with Cubism.

A cubist painter will look at your head and make a mark then draw a line the shape of your glasses going around your head. Then you might move and you’d paint right on top of it something else. To hell with it being logical. You’re making a painting and it makes complete sense. You can make it make sense. You’re not describing, you’re following where your eye goes and what it connects to next.

I’m sure that Cubism was just like, “I’m not taking a photograph. This is my experience,” and that just to bear witness to being an artist seeing something and not a camera is one of the impulses of Cubism. It was basically representational. It was tremendously experiential of what a painter goes through to see something and see it again and again. Matisse and Giacometti are doing the same thing in a way. They’re just leaving the evidence of these different takes in a painting the way Cubism does. That became okay.

To go back to structuring the painting–There’s a painting here. This is a big painting, it’s 54” by 64”, I was having a hard time holding this painting together. There are some lines in this, which you can’t see. If you go for the geometry of the canvas itself you start understanding what the geometry of the whole space is— its proportions, diagonals, and center—the golden section.

If the painting gets out of control for me, I’ll go back and I’ll find those lines to figure out what are the important lines in the painting. Often I’ll have put them there but if you need to organize the painting a little bit better and you find the rabatment of the rectangle—the squares within the rectangle—the diagonals, the center, and so on. These important lines—just in the geometry of the canvas—are useful. I’m sure painters always used these before, but we’re not taught that. There’s a book called “The Painter’s Secret Geometry” I heard about from Justin Kim (http://www.amazon.com/The-Painters-Secret-Geometry-Composition/dp/1626549265 ). It’s an interesting book. [Painting: New Providence Farm]

Most paintings were on walls then. You had to know the proportions of the room, where’s the center and how it relates to that wall over here. Giotto’s Arena Chapel in Padua is pure geometry. You can figure the whole thing out in terms of rectangles and rabatments in relation to the room, windows, and doors.

LG: How important is it to have empathy with the thing you’re painting?

MA: Not empathy, I think my painting is visual. I’ve accosted people that I’ve barely met and said, “Would you sit for a painting?” I can paint them only if they hold still. I often can’t paint people I know really well or would have a lot of empathy with.

LG: I meant more empathy of the thing you’re looking at, not so much as a person but as a, like you have to fall in love, some people they just see a subject more for its formal appeal and others want to paint it because, “They just love the view or identify with it somehow.” They just sort of fall in love with whatever it is, a group of trees, some rocks, a house, people, or whatever.

MA: I think of empathy as feeling for another person but you’re right. I guess I just bypass thinking of a landscape that way. I think it’s really visual; I look at something and I love the look of it. Sometimes it takes a long time to understand it in terms of painting. A musician doesn’t play a piece of music once and say, “Okay, did that.” You want to play it again and again and again. If that’s empathy, then yes, that’s falling in love with the look of it and wanting to paint it repeatedly.

LG: Maybe empathy isn’t the best word. I heard someone say that once and I really liked it, that they imbue human qualities into aspects of a landscape. I think I can see that in some of your landscapes. Something about the gestures or the shapes of things.

MA: You’re right, I do. I can look at a landscape and think of dance. I think of what a dancer moving through space or interacting with other dancers or just the rhythm and movement. That relates to how your eye moves in an image. You want the painting to be alive at any cost. You’re going to try to go for things that make it move and you’re taking them from the landscape.

LG: That’s a great way of putting it. Is not letting yourself be too refined about something you think about? Are you after a certain kind of quality of roughness with your painting?

MA: There’s something about being American. I don’t think of roughness painting in Italy. Italy has such a worked over and designed landscape. American landscape doesn’t feel that way at all, to me it’s a billboard landscape. It’s gasoline stations and whatever is expedient, or, “We’re going to tear this building down over here because we want something different. We’ll make more money out of this.” It’s a completely different feeling for the landscape.

The roughness comes out of how I paint. It’s not a decision to be very precise and refined about painting. I’m going to grab and run. It’s just a result of the way I go after the painting, that it can be very rough. I kind of like that. I feel that expresses who we are. All painters don’t feel that way so I guess that’s personal. I don’t go after roughness; it’s a byproduct.

LG: Do you think some painters sometimes go after that roughness intentionally and it becomes more of an affectation?

MA: Yes, but you can’t think about style. It just gets in the way. I think looking at things is so powerful that when I see things I think I’d be sick if I couldn’t try to put them down. I think it’s a way of dealing with being overwhelmed at how beautiful things are to look at. Trying to put them down seems, my greatest motive. I don’t think about other things when I’m working. I don’t always get a painting either.

LG: Good. So you wouldn’t, when you’re working outside and you come back into the studio, you’re not necessarily going to think, “Jeez, if only I’d made this line a little straighter,” or, “I didn’t quite get this thing right.” It’s not about refining it later back in the studio.

MA: Sometimes it is. Sometimes you know that that’s a wonderful straight line and I’ll take a ruler. I’ve been working with a telephone pole in Tucson and it’s got a little thing at the top, you know a little canister or something. I want it at certain angle and I want that line to be straight. I use a big yardstick that I found in the house. I don’t hesitate to use rulers or T-Squares or whatever is going to give me a strong shape or a strong line. I don’t do it everywhere. It’s a tool. I do a lot of clarifying in the studio.

LG: What about deciding if a painting is to be big or small? I noticed that many of your paintings are quite small and then some are big? I figured the smaller ones are more likely to have been done on-site outside and then the big ones are studio. How does it work? Is it really determined by some other means entirely? What is scale to you for your paintings?

MA: Small paintings are usually one-shot paintings, not always, but … For me to get my mind around the whole image, “How do I put this together here? Maybe I should be there.” I’ll do lots of small paintings. I’ll do them sometimes after I’m 90 percent finished with a big painting. It helps me get my mind around the whole image and to see it in a nutshell, so to speak.

A big painting has to be lots of different takes, lots of different times, has a much more layered feeling to it. I like big paintings. I don’t necessarily want all the layers to be congruous, if they’re incongruous that’s okay. In fact, I often will go after things that don’t seem perfectly balanced or don’t seem perfectly harmonious, like I would disrupt resolution. In a big painting you have lots more chances to do that.

In a small painting, I’ll go after it once and it’s usually to clarify something for myself in, “It’s this to this to this. How do I put that down? How do I get that?” I do that all the time. I think it’s a great practice just to constantly re-see something through a 20-minute study.

LG: How do you start a painting? When you go out, what is your process like? What do you do?

MA: To have as little process as possible, basically. I don’t want to pre-think the painting. I want to go wherever the landscape takes me. It’s hard to get away from yourself, from your habits. I repeat myself all the time; I know that. I like Diebenkorn saying, “When you start you want to get as far away from home base as you can”.

Recently I’ve been ordering canvases from Twin Brooks Stretchers in Maine. They make beautiful canvases and I usually will order something as close to a golden section as possible. I’m doing landscapes, not always, but … I really think it’s been inhibiting. I think I’m going to get away from that, just go back to the open space, that’s trying to find out where a painting would go without my pre-considering the size of the painting or the shape of the rectangle.

What else can I say about that? I don’t have a plan. It’s very embarrassing to go out and paint where people are going to watch you because they must think, “God, that person is absolutely crazy. What is she doing?” I like to be alone when I’m painting. I was at Mount Gretna School of Art. I’d get up at 6:00 in the morning and go out there, other people get up at 6:00 in the morning, too. Somebody comes up to me and says, “Do you do this often?” I’m out there trying to figure out this landscape. They can’t make head or tail of what I’m doing. People would never read over a writer’s shoulder and comment.

LG: I also find that difficult, because I sometimes paint in a suburban area, on the sidewalk in front of people’s houses and sometimes people can see me as being very weird.

MA: I think it’s very brave.

LG: I’m used to it but it does worry me sometimes that painting in public can influence how you paint. Despite knowing it’s ridiculous, I sometimes feel I censor myself from doing anything too wild because someone might come by and think I’m a nut. If I don’t paint realistically, then they’re going to think I’m wacko. Of course this is totally wrong, so I increasingly want to find the more remote places to paint or just stay in the studio. However, it’s probably wrong of me to say this but if I’m painting in more urban areas, with lots of homeless people around, I usually paint a lot better. I might get hassled or even robbed but at least they’re less apt to be judging my painting.

I don’t know if you ever have anything like that. It’s why I think it’s so great that your recent paintings increasingly seem move away from the presence of people. More pure landscape.

MA: Absolutely, I feel exactly the way you just described. I was painting in France and people would bring their school of artists up behind me and very quietly and in French mumble things. I would just be beside myself and know, “I’m going to have to scrape this entire painting as soon as they go away.” I would tell them, in French, my limited French, “Go away and come back when I’m finished. I can’t talk to you now.” I can’t talk and paint. It would drive me nuts. They would come between the painting and me and ask me questions.

LG: I heard Ken Kewley say something that helped me with this once. He said to be a good painter you have to be willing to risk looking like a complete idiot. Just paint and don’t worry about appearing crazy. He talked about once bringing a class into a grocery store and having them draw fruits and vegetables in the produce department. I could never do that, especially if I was trying to draw in an abstracted manner, in a grocery store. I can’t imagine anything harder. I like to think this is sometime to aspire to, to be able to lose my sense of inhibition, but there are many things I need to work on before that.

MA: Listen, it’s one thing to talk about it afterward. It’s another thing to be there. I think if you’re in a group of people doing that in a grocery store, you’re safe, you’re okay. If you’re the only one, oh no, I don’t think so.

LG: That’s very true. There’s safety in numbers.

MA: I know a lot of painters have no problem with this–stand outside the subway in New York City, no problem. Actually, you’re probably safer in New York City doing it. In a suburban grocery store I don’t know.

LG: They would probably have the security guard come and take you away before you got very far.

LG: Where do you usually paint? What are you painting these days?

MA: My favorite place to paint is certainly in Vermont. We’ve had a cabin up there since ’69 and it’s just a place I know really well. I almost know every tree, every branch, the way the light comes over the hill. It seems endlessly interesting to me, endlessly varied. You go from winter to summer to fall, the colors. I love to paint there and I’m absolutely alone, so far.

I love to paint at the ocean. I think the ocean is an awesome subject. Although, we haven’t had many opportunities to do that. When I’ve had chances to paint there, I think, you could paint there forever. It’s endlessly complex and interesting even it’s absolute simplicity. If you don’t put sailboats and rocks and too much other stuff in, it’s just an abstraction and it’s such a challenging abstraction.

I also love painting in Arizona now. It’s like being on the moon, these huge saguaro cacti that are all over the place. All the mountains in Tucson are geometric; they’re very new and very jagged-y. It looks like somebody put big blocks out there. I’m painting a mountain called Sombrero Peak and it looks like a big saddle, then on one end it has what looks like a hat. It’s an interesting form and there’s all the stuff in between, lots of telephone poles. Nobody runs lines underground; it’s all rock.

LG: There is sometimes a gestural flow, a linear movement in your paintings that brings Poussin to mind for me, is there something to this?

MA: I wish I had a relationship to Poussin. I admire him tremendously as a painter, that he could make such solid form in a painting. His drawings look modern. His drawings sometimes look like Cubist drawings or Impressionist drawings. They’re so quickly done and they’re so structural at the same time. The paintings and drawings are solid. I think if I could teach a painting class and say, “Okay, all I want you to do is draw from Poussin’s paintings,” that would be the whole class. You would learn how to draw. I think they’re amazing paintings in that regard. Cezanne said something like; he wanted to do nature over from Poussin…

When he had to fill out some sort of questionnaire when he was young about who was his favorite painter, he mentioned Rubens. When you look at the touch in Cezanne and the touch in Rubens, you can see there’s a startling relationship. You can see Poussin in some of the paintings of his wife, the figures become rocks, like he’s painting Mont Sainte-Victoire in Hortense; there she is, a rock. I love that quality in his work but I don’t see it in my work … That’s not me.

LG: I was thinking more of a relationship similar perhaps to when Jackson Pollock studied with Thomas Hart Benton, Thomas Hart Benton was all about these gestural flows and rhythms arabesque movements through the painting and how one figure’s gesture will blend into another one and go into some part of the landscape or something like that and then it turns around and comes back. It’s like an underlying curvilinear structure.

I think Pollack perhaps got a similar sort of curvilinear gestural flow through his paintings. I think that with Poussin and Rubens you see a similar thing with the gestural flow through all the things that relate to each other … how a line will extend through a figure, through the axis of a figure into the axis of a tree and the way the branch flows down that will go into some clouds and will come into this and when you start looking at it, it’s all over his paintings. Not so much in terms of the structure of the forms, which is a whole other thing, but I think I see something like that in your paintings. Perhaps like how in your landscapes certain lines of the tree branches would relate to gestural lines in other trees or elements in the painting … There’s a whole curvilinear rhythm in your paintings that seem to have a baroque feel to it.

MA: I love what you said about Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollack, I never thought of that and I’ve never read that anywhere. That’s really good, I like that. In my work I think it’s from spending a long time drawing in museums. The more you draw from old masters, the more you see that constant making of relationships, or this rhythm is echoed by this rhythm. I think it’s an idea about drawing that goes back to ancient wall paintings.

LG: In medieval art you have that same sort of thing. I thought it was brilliant you were saying how the early Renaissance blended the medieval linear rhythms with the observed world.

MA: Sometimes we forget that. Sometimes we forget that you can get very representational painting from a photograph, but you don’t get that abstract sense of constantly making relationships in the painting. The human element is outside the photo.

I was looking in the Norton Simon Museum yesterday and you see all these Indian reliefs and they look elegant like they could have been done in Venice in the Renaissance. They’re second century, not Renaissance, they look like Greek reliefs. They show what happened on little steles that you see in Greek art where you have two figures here and have another figure there and then how the artist relates the three of them. Maybe you have an animal of some kind. The beautiful way they’re put together, the way they’re structured. I think that’s really forgotten in a lot of modern painting that comes from photographs. It isn’t there anymore. I think it goes way, way back. You could see it in tomb paintings from Egypt, this wonderful sense of making things relate to each other and putting them together, composing them so that they have unity. That’s interesting.

LG: Does your painting have an affinity with the early modernist landscape painters, like Arthur Dove, John Marin and others–can you say something about your relationship with them?

MA: One of the things about them is that they’re non-academic. I can feel an affinity with them in a way that they just went out there and they painted from themselves, they made their own images of what they were looking at. Of course they were looking at everything and other painters and of course they had teachers. I am bemused by teachers who say, “It has to be like this and these are the rules.” Dove, Marin and Hartley started from inside themselves, not armed with academic dogma. They also seem to represent an earlier simpler America–maybe a myth but we treasure that.

I feel much more at home with them and Burchfield because they trusted themselves, they didn’t need somebody else’s rules. That’s what makes them so refreshing for us. You discover your own by working. Where did Picasso get his ideas?

LG: Can you tell us something about the workshop you’re giving this summer in Italy and your approach to teaching?

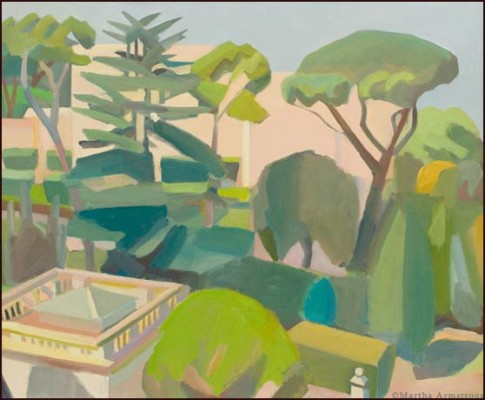

MA: I’ve been painting in Italy since 2000, and I first went to Italy when I was in college on the Experiment in International Living. I went one summer and lived with a family, and I fell in love with Italy, it was home away from home. I love the Italians, they’re incredible people. The landscape is so ancient, so lived in. When I was first there everything seemed like art, I was frozen in terms of trying to make my own drawings. But it didn’t feel that way when I went back as a painter after I got out of school. Italy has such a complex history, and it has such beautiful light and atmosphere. I’d had enough experience finding my own voice to bring to it when I went back. You want your own response. Imagine ten people improvising from a piece of music. You desperately want to know what you would do.

The history of art is present everywhere in Italy, you see it inside and outside. You see it in the landscape and then you go in a museum, it’s there in the paintings, the people are in the sculptures. It’s an important experience for a painter. Everything feels present; the traditions seem alive in Italy. It’s not as if, “Well, this is an old dead culture and we don’t have anything to do with this anymore.” It’s not like that.

LG: What about Monte Castello? You’ve painted there before; you’ve been involved with the International School in the past?

MA: I went in 2000 to teach Hollins’ January term and stayed there after the students left. We were staying in Todi—an Etruscan town, elegant and spacious—and painted in Monte Castello di Vibio, a small mountain town given to a Roman soldier whose family name was Vibio. The town is charming, medieval and cozy. Both have magnificent views that are fascinating to paint. People are very respectful of the artists working. It is a perfect experience for a painter.

LG: How do you go about teaching your workshops? What can you say about what someone might expect.

MA: This workshop is for people who are into painting, I’m more of a group leader, and I’m not running it as a class. We will get together and talk about painting, and the painters coming are serious painters. We will simply get together and exchange ideas and talk about each other’s paintings. I’ve been teaching landscape for years, I can hardly keep quiet about it. The one criticism I’ve had as a teacher over years and years is that I don’t tell students what to do. (I do tell them, “You’ve got to deal with that tree!”)

I want them to make their own decisions. I can raise issues and make suggestions but I don’t tell them what to do. I make them decide because I think that’s really what painting is about. Moments when I have been overbearing and telling them what to do, I usually find I go into my own studio and make a liar out of myself. As soon as I pick up a brush I’ll do something absolutely contrary to what I just shoved down that student’s throat. I’m really conscious of that, and how quirky painting is that way. It’s something that you don’t own; it’s just there. Stay out of the way.

This summer I want us all to go out and paint every day. Think about it later. Throw ourselves into the landscape and make lots of paintings good and bad just to see what’s there, what we choose to put down, and talk about it later. Go to Florence and look at paintings. By the end of a week we will be thoroughly immersed and have something to wrestle with. I want everyone’s work to be his or her own.

LG: I often find that whenever I start hearing someone say that painting is supposed to be made a certain way, I immediately start counting reasons why that’s really not true.

MA: You got it.

LG: There are very few rules in painting where the opposing opinion isn’t equally valid.

MA: Bravo. Exactly.

LG: But still if you don’t even know the rules or don’t pay attention to them simply because good color or drawing is too hard, you can still make crappy paintings, especially if you try to paint like you’re the first person ever to pick up a brush. There are lots of people these days who have a mindset of wanting to “deskill like crazy”.

MA: I agree with you. It’s too simple to say that there aren’t any rules. All of art history is there setting rules. You don’t want to get too hemmed in by your own ideas. I started with this classic ballet teacher–there is nothing more demanding than ballet in terms of rules and correctness. You have to quit because you don’t fit that image, you are not Suzanne Farrell.

Suzanne Farrell was in my ballet studio growing up. She became George Balanchine greatest dancer. She had a perfect body for ballet. In painting that doesn’t happen, and in a lot of modern dance it doesn’t either. I mean you can be all over the place, you don’t have to have a perfect body. In classical ballet, that’s the way it is. The “Leap Before You Look” exhibition on Black Mountain College shows you where dance and art went in the ‘30s. I was out of classical ballet before I left high school and into Martha Graham and Agnes De Mille. When you’re young the ferocious discipline feels important, but as you get older you want more—invention, expression, feeling—how does this feel—as a judgment coming out of yourself in the present. There is something ethical about that. Students need to get there.

LG: Thank you very much for this interview.

Selected Writings on Painting by Martha Armstrong

Excerpts from the catalog: Some Conversations with and about Martha Armstrong, Painter

“The fight is between what is and what you can get—want to get—in the painting. If you just take everything you want and forget the subject matter you lose the meaning urgency of the painting.”

“When I look at paintings I’m looking for something real, something to hold you down to earth. I’m looking for connections.”

“The artist makes your eye move. Compare a photograph of a man in front of a barn to a Roman stele. I think this is what Leland Bell meant when he spoke about painting the arabesque.”

“The painter’s problem is to make his work feel it will hold up like architecture. It’s a fake, you can put anything down, it doesn’t have to hold up, but I want my paintings to feel that they do hold up, have that kind of balance.”

“Pictures: the quickest ones are comics. They have to be fast, essential. Picasso knew that. The model for Guernica is the Katzenjammer Kids, which Picasso read for years, but what he made from them! We don’t think “comics” when we see Guernica.”

“Each piece of a painting should bear significance like the words of a poem—resonant, signaling.”

“It should carry more than a description of something. You want the shape to be interesting itself but also to carry meaning beyond description of a limb or tree. You want something beyond the landscape itself.”

“Making images is as old as human beings. In a way photography has thrown us off to think that painting is only about pictures. Photography has led us to advertising.”

“When I start doing something and realize the camera can do it better I realize the absurdity of what I’m doing. Much of the history of painting is based on images the camera can do better.”

“At one time some painting had the purpose of some photography today — to make a record, capture a likeness exactly. What would Holbein draw today? For 30,000 years, from the earliest-known cave paintings, painting revealed an internal life rhythm, heartbeat, dance, breathing. The photograph cannot give that. When we see ourselves in a photograph we see ourselves static, dissociated from our life rhythm. That’s our image of ourselves today.”

“You draw from an Albrecht Durer etching, it’s like crawling around in his mind, it’s so structural, yet it’s so flat, it resolves flat so it sits perfectly on the surface. Strange. Poussin: his work is the most logically three-dimensional. I should always be drawing from Poussin. Cezanne said, ‘I want to do Poussin over from nature.’“

“Paintings have to be about the meaning of visual form. Representation is only one of the tools.”

“I don’t think you can learn about these things without really studying drawing and looking at the past. There’s a lot of past in painting.”

“The search for meaning in a painting is not superficial or quick any more than it is in looking for meaning in a Keats poem or in a play by Sophocles or in a piece of music by Prokofiev. Creativity is not cleverness.”

“Creativity needs room to play and be wrong and experiment and go where you don’t know where you’re going. It’s true what Veronese said to the judge in Venice: ‘Artists must be allowed the same latitude as children, drunks, and the insane.’”

“I don’t want anyone to outlaw my craziness or make me feel self-conscious about my studio being a sandbox.”

“I feel there’s something wrong with a painter when I look at his work and it doesn’t make me want to paint – which is true of much painting today. It looks impressive, but it is digital and it is dead.”

“A painting should have a sequential feel to it, something that could happen over time. It can be the exploration of an idea, or something you imagine, but it is an exploration. You can hear the human mind working in a painting by Matisse. You can feel the drive in Picasso—the unstoppable expression. It has a heartbeat, it has a rhythm, it has a pulse, it is alive. A wall painting from Knossos has that, a Braque still life has that. It’s not different over the centuries.”

“So much art today feels like it was done for the audience—to show what the artist could do, or to please someone else. Then you look at a David Park and realize he did it entirely for his own reasons.”

“It’s much easier to paint a small painting. You can get away with murder in it, and no one will notice. If the structure isn’t right a big painting won’t hold up. A big painting has to be simple and can’t hold a lot of detail.”

“Classical landscape has background, foreground and middleground. Modernist space takes from abstraction: everything is on the picture plane, everything sitting on top of everything else: intimacy.”

“An artist who works from life wants the image to feel like a glance, a snapshot, the way Edgar Degas has figures halfway into a painting as a photograph might catch the image. Yet the painting must be fully composed. A painting has its own imperatives of composition that have little to do with the subject.”

“Lots of artists today use photographs as subject —from Picasso to present day artists. It is different to compose from life—from the eye, through time, to the hand to the canvas. It is more like playing a piece of music—you must know it to some extent, you must concentrate completely to make one thing connect to another. Unlike the musician you can correct or change later. But the painting is basically there. Painting draws on the whole mind— intuition, sensation, intelligence—in a way that the manipulation of photographic information does not.“

Excerpts from the catalog: Martha Armstrong, Recent Paintings March 1998

“A painting has to come to terms with everything the artist has experienced, everything suffered, enjoyed, felt, understood. It has to have that kind of complexity. Nature has that immense complexity. Think about collage, fractures, dissonance, playfulness, exuberance, pain, anger, everything.”

“How do you get that if you stay with straight representation? Abstraction doesn’t connect to anything. The full impact of photography is coming to bear on painting.

“The only way I can keep my painting from feeling frivolous is to stay very close to the fact of the landscape. It is mundane and has its own peculiarity. Thee only justification for changing anything I’m looking at is when I can’t paint it straight—when that will not get what I see. But painting is always a translation—an illusion, not an appearance.”

“Seeing—and the painting that comes from seeing—can only be one way at a particular moment. Some paintings are done in a day; some have pieces of many days. To get what you see you cannot paint what you see. It’s a battle between what you see and what you know. You take what at you need to make a painting. The landscape has everything and nothing to do with the painting.”

“What you’re trying to do in painting is make the marks, forms and colors bear all the weight of reality and of feeling. I get at this best painting outside—the studio without walls.“

Stanley Lewis on Martha Armstrong: (From Martha Armstrong: Up to Now February 19-March 14, 2009 Gross McCleaf Gallery catalogue.

“The problem with American Realist painters is their tendency to feel obligated to describe reality because it is there and in the most obvious way, skirting the nagging feeling that perception is originating behind your eyes, not in front of them. This is a problem I have. This is the hardest problem you face when you get outdoors ready to paint: “What am I seeing?” Martha seems to say, “I’m going to paint it like this because I just got a message to do it.”

“Martha’s friendship has been important to me. She helps me define how I could be different from my teachers. I want to take on some of her defiance toward authority. I feel better after we talk. She can give a push in a positive way. She is a great teacher. We have always liked each other’s paintings. It is important to have good friends.“

Fascinating interview, great quotes. I love the depth of thinking about what painting is. Thank you for posting it.

My regard for Martha and her works run deep because her challenge to herself is so fundamental to being authentic in her painting.

Her repeated painting from a similar motif reveals just how deep and wide visual experience is when you come to it without preconception

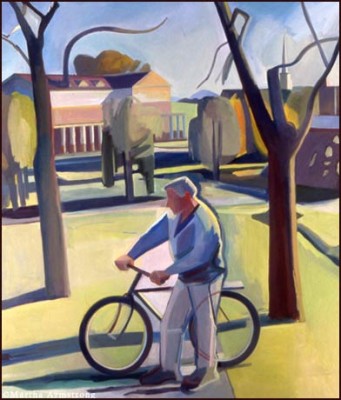

Martha provide a great model for the students at Hollins University when she joined us as a visiting artist several times in Italy and on campus. One of her paintings of Alan with his bike on the Hollins campus is currently in the exhibit Friends & Neighbors at the Taubman Museum ofArt in Roanoke Va.

Thank you for posting this interview. I found it very insightful.

I have been a big fan of Martha’s work for many years. At the risk of sounding simpleminded, I want to say her work is fun to look at, but in a serious and sustained kind of way. Delightful to see all the images!