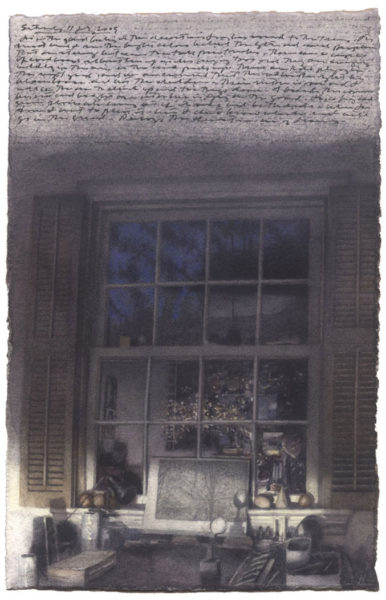

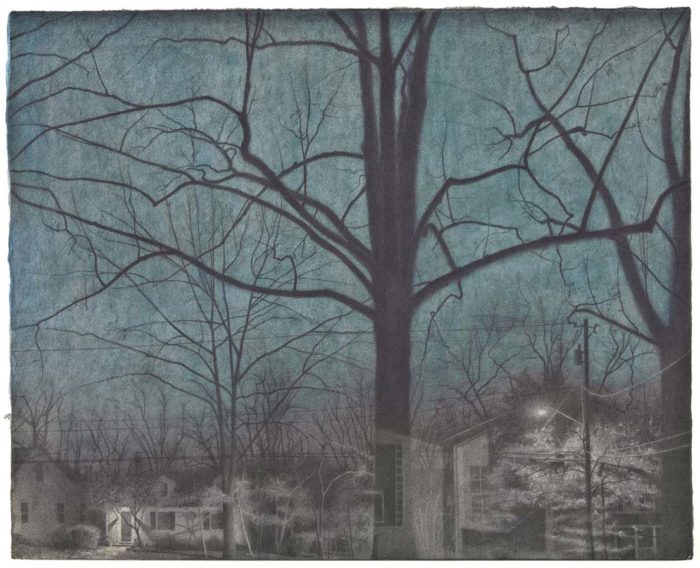

Self-Portrait with Twilight, Work In Progress, 6 x 4″ September 9, 2009 watercolor, gouache, graphite, and pen and ink on Fabriano paper, Sixth state.

I am pleased to share this email interview with the incredible Silver Spring, Maryland based artist Charles Ritchie who for the past 30 years has drawn from his home and neighborhood as the starting point for deeply personal drawings, journals, prints, and paintings. Ritchie has made 143 complete volumes of his art journals since 1977 many of which can be viewed from his extensive website which offers an unforgettable and mezmerizing display of his many forms of artmaking.

In a 2014 Houghton Star essay Hope McKeever wrote:

Ritchie works from a chair in his home, slowly creating a layered representation of the metaphysical world using watercolor, graphite, pen, and ink as his tools. He attributes his unique style of creating to rebellion. Rebellion against the way he was brought up. He moved a lot as a child, and he finds the stability of his home liberating. However, he does not settle for stagnancy. He described how he enjoys “getting to know the world in a profound way through limited experience.” He compared this process to the life of a musician. A musician practices scales every day and listens to the rhythms and musicality of the notes. Ritchie described how he wants to be a receptor of the beautiful art that proceeds from his study of the observable world.

He sees his methods as a skill that takes time and patience to acquire. “Training the eye and hand has helped me isolate what is important,” he mentioned. His impeccable knowledge of color value is one of the important tools that he uses to create this isolation. Because he primarily works in black and white, Ritchie described how he must use the full range of color that these two colors offer. In a value class that Rhett taught, he used Ritchie’s work as an example of exceptional use of value. Rhett encourages his students to observe contrast between colors in their work instead of framing every section of color with lines.

Along with contrast in value, Ritchie studies time as a crucial element in his work. He finds immense importance in the stillness of time and the movement of time. Without the movement of time, he would not be able to capture the changing shadows on the wall, yet without the stability of time, he would not be able to document the reverently still environment. Both are crucial elements in his work and his observance of the world. He strives for moments that become “iconic rather than fleeting.” For example, Ritchie explained that he is currently working on a project that will take many years. He is observing the growth of an oak tree as it slowly adds layers to its core across a wide span of time, mastering the art of transitions.

Humility translates through his work because he realizes that he may not be alive to finish some of his projects as he believes, “no decision is final.” His work constantly evolves, creating an accurate representation of how his “inner voice” evolves with his work. Laurissa Widrick, a senior art major, observed this evolutionary aspect of his work and marveled at how, “his process is a lifelong commitment.”

Because his personal life connects so closely to his work, Ritchie’s own voice is the primary one that translates into his work. His inner voice, “the dream voice” as he calls it, captures the “train of consciousness” that goes through his mind during his early morning meditation times. These dedicated early morning reflection times are essential to the consistent patience that he exercises in his work, Rhett remarked. Ritchie finds solitude extremely important in the spiritual act of studying the inner voice and the psychology of self. He concluded that, “I think in a way, one’s spiritual world depends on those things.” This spiritual element permeates through his work turning small-scale pieces into scenes portraying vast universes that are easy to miss in a quick glance.

Ritchie is represented by BravinLee programs in New York, NY and has had solo shows at many notable venues including Houghton College, Houghton, NY in 2013 and Georgetown University, Washington, DC in 2012. He has received numerous awards including 2013 Ballinglen Fellowship, multiple Individual Artist Awards from the Maryland State Arts Council, 2005 The Franz and Virginia Bader Fund and a 1999 The MacDowell Colony Fellowship. He has been reviewed by leading publications including: Art News, Haber’s Art Reviews, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Washington Post, Richmond Times-Dispatch and the Boston Globe. Since 1988 Mr. Ritchie has worked as an Associate Curator, Department of Modern Prints and Drawings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. He received his MFA in painting in 1980 at Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, and a BFA Graphic Design in 1977 at the University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

A solo exhibition of the artist drawings is currently being planned for 2017 at BravinLee programs in NYC, NY

Larry Groff: What was your early experience with art like and how did you decide to become an artist?

Charles Ritchie: Children’s books were my first introduction to art. My favorite subjects were nature, outer space, dinosaurs, and history. I had probably decided to be an artist by my early grade school years because I was writing stories and illustrating them, mostly improvising on subjects that I knew from my book collection. By high school I encountered the most wonderful art teacher in the North Carolina Public Schools. Ethel D. Guest helped me find discipline and focus in my work and guided me towards the Governor’s School of North Carolina, a summer high school program that, in turn, gave me the confidence to move towards studying art in college. By the end of undergraduate school I was eyeing ways of putting wheels under a career as an artist.

LG: Was art school a positive experience for you?

CR: University level art school was mixed experience. I saw the 1970s as a time of near-nihilism in art transitioning into minimalism and conceptualism. I felt completely out of step by wanting to learn to draw traditionally. Nevertheless, I sought out the individuals that I felt could give me guidance. I studied everything that I found inspirational and learned by experiment, doing a lot to teach myself how to draw. Most significantly, by the end of my college years I had discovered the importance of going to museums to study and copy works firsthand, a practice I continue. I had also begun to acquire my personal library of art books and postcards which I continue to cultivate and consider to be formative to my development.

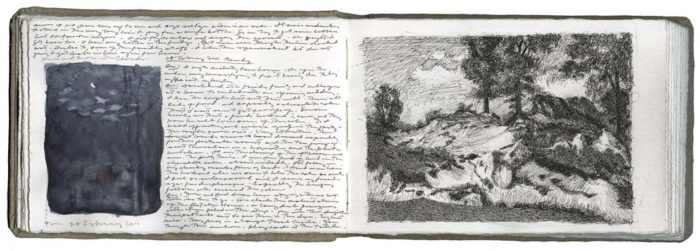

Two Studies, One After an Oil Painting by Camille Corot, Book 135, 4 x 6″

pen and ink, graphite, and watercolor on Arches paper in bound volume, open book size: 4 x 12″ 2011

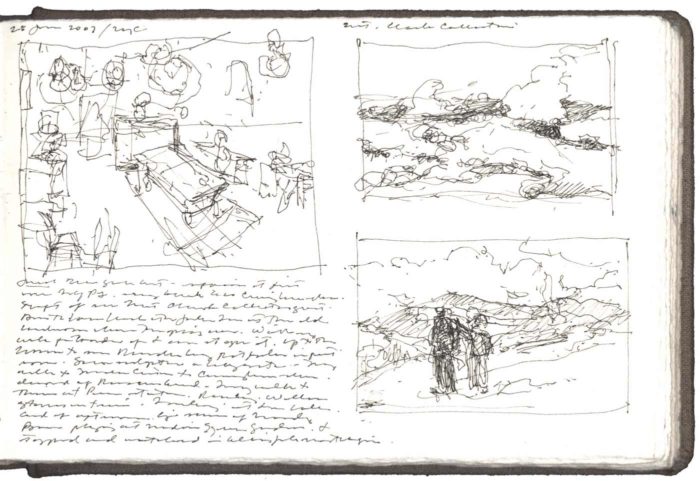

Three Gesture Drawings after Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh and Winslow Homer, Sheet: 4 x 6″

pen and ink and watercolor on Arches paper in bound volume, Studies made at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

LG: Which artists do you look at most often and why? How much of an influence does this have on your own work?

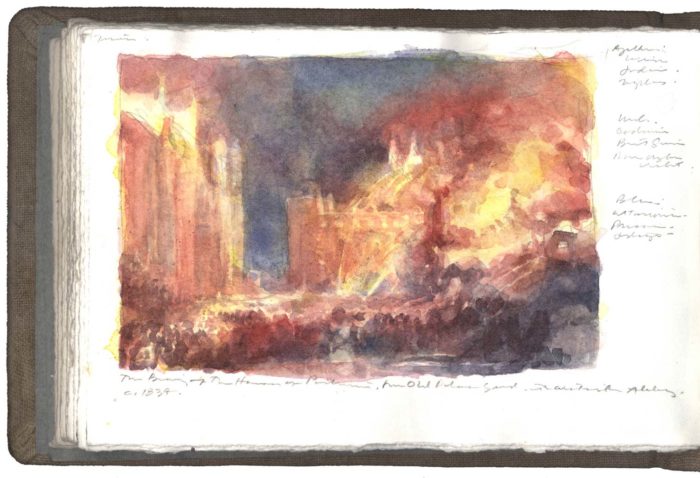

CR: I’m drawn to works on paper and my biggest heroes tend to have a large graphic component in their catalogue: Michelangelo for his breathing line, Leonardo for his layered atmosphere, Caspar David Friedrich for his luminous transparency, Camille Corot for his tonal sensibility, Winslow Homer for his fearlessness and economy with watercolor. I also look closely at many works that may not relate immediately to what I do. For example, I love Robert Rauschenberg’s early work. Some of his surfaces look like they accreted naturally on the support. How does one do that? Or his Erased de Kooning Drawing, after two months of erasing, the faint image that remained on the page was ghostly and sublime. Could I somehow apply these ideas to my practice? I try to take in everything because I might be able to use it eventually. I believe the works of other artists have had a profound influence on my own because when I understand their practices, I can apply what I’ve learned to inform and improve my own art. I also believe that unconscious transference occurs. For example, when I write down my dreams in my journals, I feel like I’m taking dictation. It’s exciting because I’m letting my subconscious take over. But when I go back and read through the dreams I’ve written down, they seem to be filled with symbols that can be related directly to what I have experienced in daily life. I believe a subconscious transference also takes over with the images I absorb, the ones I’m looking at in my world and the images by the masters I’m observing and their echoes are reconfigured in my art.

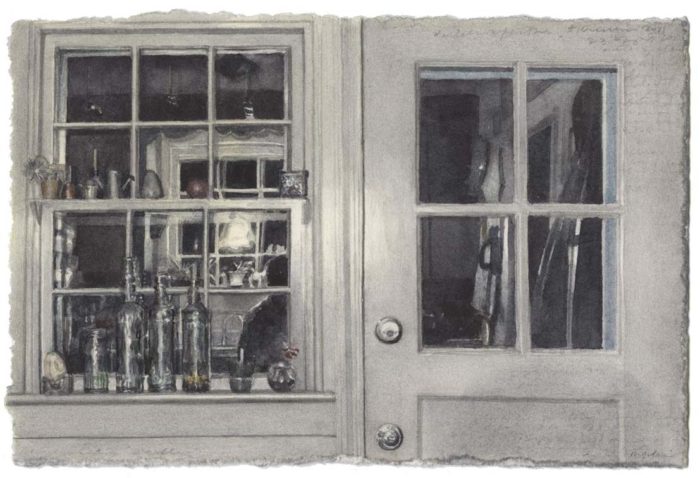

LG: Your primary subject for the past thirty years has explored how you see light in your suburban home. Why stick with this subject for such a long time?

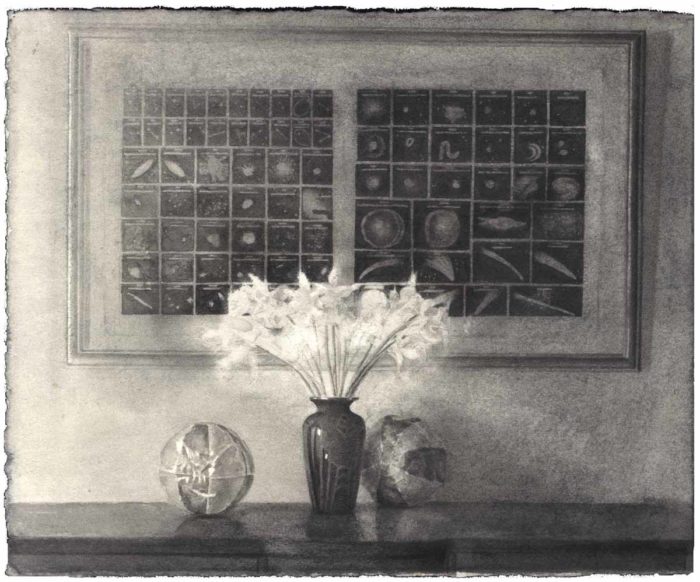

CR: A good way to introduce the subject of Giorgio Morandi’s work is to say he painted bottles. But, of course, his work really is about many things simultaneously. As far as my work goes, yes, light in the suburban home is a good way of introducing my project, but for me there are so many other things that are growing and shifting in the work. My perceptions about my subjects continually change, abstract arrangement of forms make new connections, techniques emerge that can take me new places, I develop new tonal and color arrangements that lead me to even greater challenges. That’s where the excitement comes for me. Painting in the same room and observing from the same window after all this time, I feel I’m looking deeper than ever, building on more and more experience. My friend, author Peter Turchi, has called what I’m doing a “private astronomy.” Indeed, my room is an observatory and I’m simultaneously scoping inwards towards myself and out my window towards the edge of the universe. The cataloguing and study of my world remains far too interesting for me to step away.

LG: Despite the close observation and realism of your work it often seems more about visual poetry and imagination. What gets you past just recording what you see into a more personal or inventive realm? What can you say about meaning with your works?

CR: For me, time is the essential ingredient. My works usually gestate over long periods. My mental images of my subjects have accrued over more than 30 years now. There are many memories and associations. I’ve seen these subjects change: in an instant, over the day, and over many years. My drawings condense observation, memory, invention, and accident. As for meaning, I hope to leave as much space as possible for the viewer to invest themselves in the image. My works often have symbolic resonance for me but I usually discover it after the fact. For example, in 1994 my daughter was born and about the same time I finished a composition called Daffodils with Astronomical Chart.

Daffodils with Astronomical Chart, watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on Fabriano paper, 1993 – 1995 Image: 4 11/16 x 5 1/2″ Sheet: 4 11/16 x 5″

I hadn’t considered this drawing of blossoming daffodils as a metaphor for her arrival until afterward. But I don’t think anyone has to know this background to appreciate the work. In fact, I’d much rather hear what my compositions bring to viewers than try to come up with what they might mean to me. I’d prefer my art to be an opening force rather than limiting one. As for getting into a personal realm to work, well, for as long as I can remember, I’ve been a very early morning person. I rise around 3:30 am and sit down at my table and fill my journal with my dreams. I begin to draw as I’m coming out of this dream state. The early morning hours are a quiet, very private time for me and key to entering a creative state. I’m lucky that it matches my body clock.

LG: Your works are often small; like a 6 x 4 inch notebook sized, but may require many years before you consider them finished. The many erasures and revisions produce pentimenti, which you called “an archeology of surface.” Can you speak more about how your process and what goes into deciding when a work is complete?

CR: When I see something that stirs my curiosity I make a quick sketch in my journal for reference. I usually refine my idea over time and when the basic elements and composition have coalesced, I select a sheet of paper outside the book and tear it to the right size and shape. Working in front of my subject, I slowly refine outlines in pencil on the sheet, then add transparent watercolor washes; yellow first, then reds and blues, building to darks. I tend to work on multiple drawings at once and I generally have two seasons of drawings: one for the half-year that the landscape is foliated; another developed while the landscape is bare. I switch between the sets in the spring and in the fall. This losing of drawings for periods of time is actually useful. They become unfamiliar and I have to reacquaint myself. I also find myself applying new energies and processes I’ve acquired in the intervening time. I often look at works for a long time before they are done, and am very apt to go back in using subtractive techniques: using various erasers, scratching into the page with a single-edge razor blade, scrubbing with a damp bristle brush, or sanding. I’m attracted to subtraction because of the reinvigoration and re-illumination it can induce. Regarding, the decision about when a work is finished, I stop when I sense that by removing any more light, I will destroy the integrity of my image. Working primarily in watercolor, one realizes that the unpainted sheet is the brightest white it can be. You start taking away light when you paint into it. All of my energy is attuned towards preserving light, while exploring the possibilities in my image. To help with this, I paint only with transparent watercolor, which enhances luminosity. The best path is one that preserves as much light as possible while articulating all of the other levels of the image: connection to an original inspiration, balance, tension, color, tone, texture, reflection, variation, and evocation. In the end, the decision to stop is intuitive. I use all my experience to decide and then I let go.

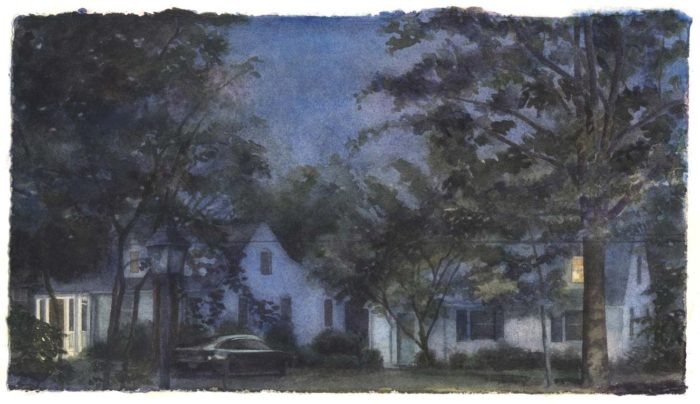

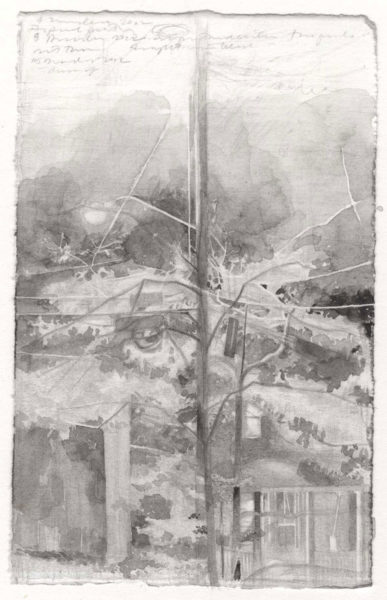

Landscape with Four Lights, work in progress, 4 1/8 x 6″ watercolor and graphite on Fabriano paper, 2015

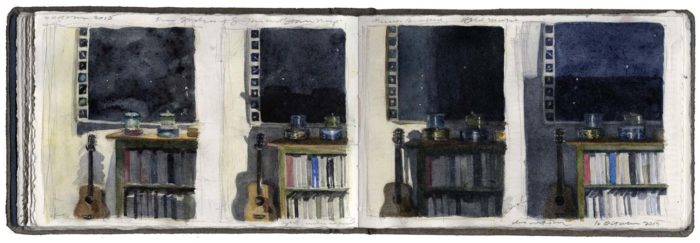

Four Studies of a Guitar and Star Map, Journal Entry, Book 143, 4 x 6″ watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on Arches paper in bound volume, March 2, 2016

LG: How did your journals evolve and what makes them so important to you?

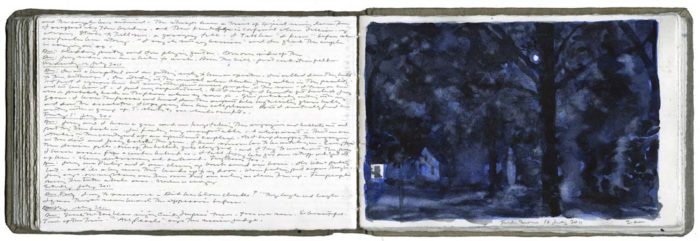

CR: I left undergraduate school in 1977 and realized that having a small sketchbook in my pocket to record thoughts and images was an immediate grounding in a world of distractions. Working with pen and ink on paper in a palm-sized book had an immediacy and a feel that appealed to me. The content in the books has evolved over the years. Originally, there was a lot of open page with phrases and line drawings, mostly my attempts to track my thinking and seeing in the everyday world. Eventually, I started dating entries and began writing longer, more involved entries and also integrating images in black watercolor and brush. Dreams eventually presented themselves as an interesting way to push deeper toward my subconscious. When my wife and I moved into our home in 1984, I started working out of the same window and began to record the subjects I continue to work with. Eventually, the primary colors and then secondaries entered the mix and the journals became even more packed with images and writing. What I like best about my collection of journals is that I can look back over the chronology of my life and pick up recurring threads within the images and writings. The journals are the spine of my project. It’s very rewarding to look at my shelf of 144 books (and counting) and know that I can stride the years and see a picture of who I was at so many moments. I also appreciate what my dealer John Lee of BravinLee programs says about my books; they are stay-at-home travelogues. I do see myself as trying to see how far I can go in a single place.

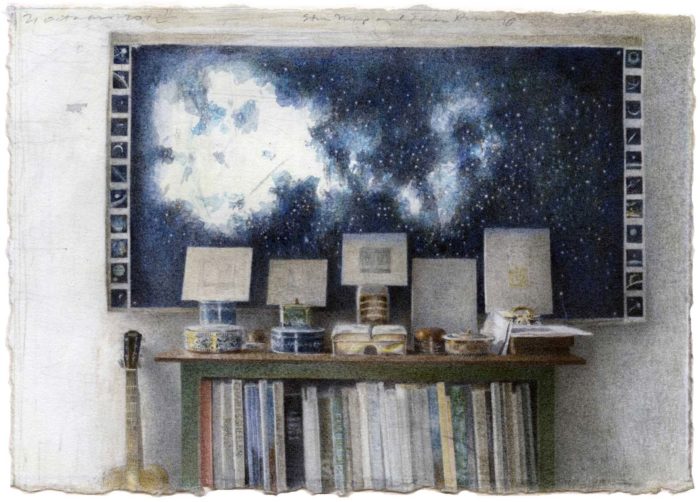

Star Map with Five Drawings, “Work In Progress” 4 1/4 x 6″ watercolor, graphite, and gouache on Fabriano paper, Begun 21 October 2012.

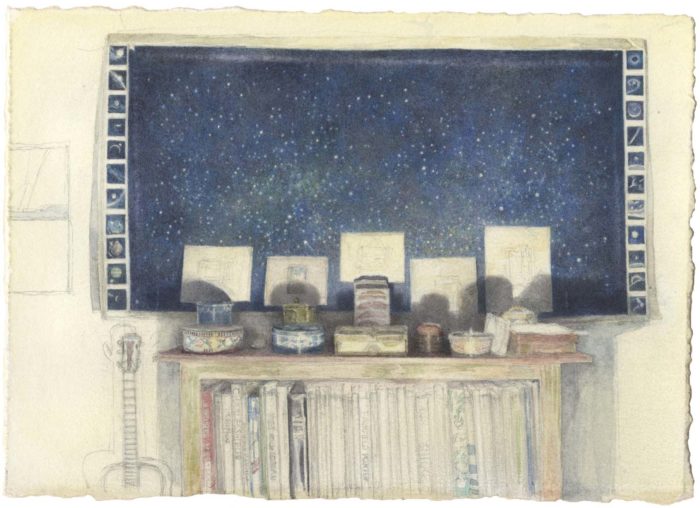

Star Map with Five Drawings II, “Work In Progress” 4 x 6″ watercolor, gouache, and graphite on Fabriano paper, Begun begun 22 January 2016. First state.

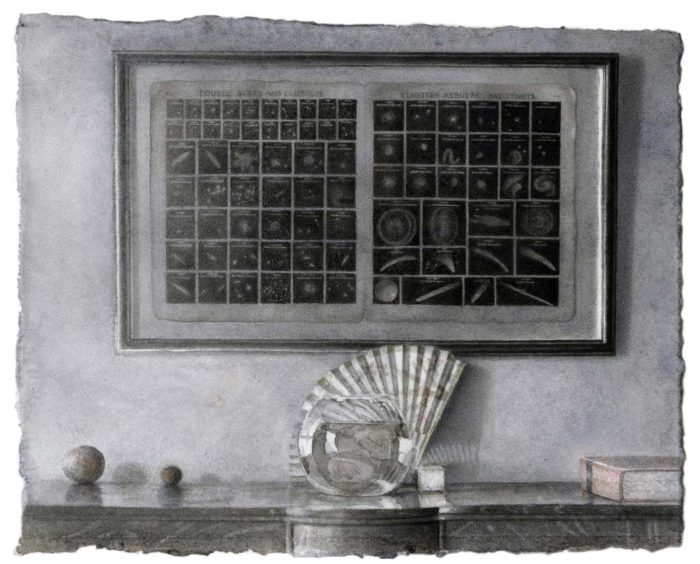

Astronomical Chart with Bowl and Fan, 4 5/8 x 5 3/4″ watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on Fabriano paper, 2015.

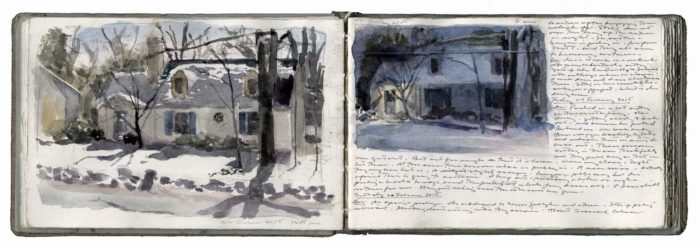

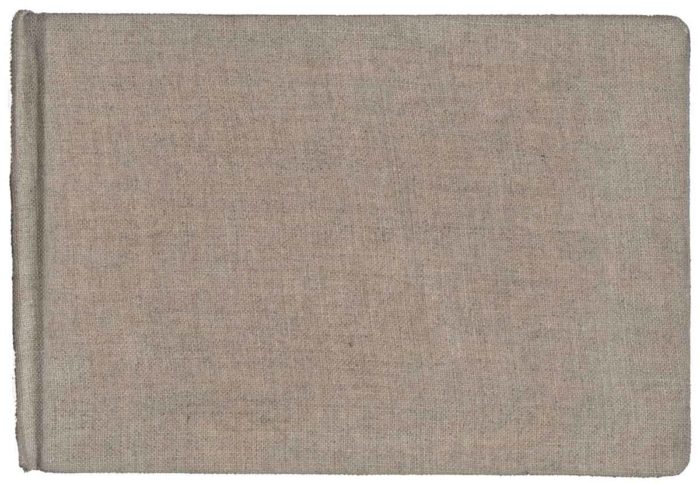

Late Winter / Midsummer 2015 Bound volume containing 104 pages. Sheet size of the original book is approximately 6 x 4 inches. Primary media include watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite.

LG: These notebooks and journals are handmade and beautiful objects on their own. Can you tell us more about what goes into them?

CR: In one of his late poems, The Planet on the Table, Wallace Stevens obliquely described his collected works: “They were of a remembered time / Or of something seen that he liked.” That’s a good distillation of what I put in my journals. Mostly the books are focused around images I want to explore combined with written remembrances of my dreams. In addition to making preparatory sketches I also copy other artists works that I admire. I write down technical information and approaches I want to try on drawings. Sometimes I copy quotes and occasionally I’ll make an observation about the day. As far as the construction of the books, until 1991 they were manufactured blank books – I want to emphasize that no special handmade books are needed to do such a project, and that each artist should find the style of book that fits their body and program. Eventually my wife Jenny wanted to take over the making of my books, she’s quite an artist herself and an exquisite craftsperson. So, I tear the paper to size and she sews the signatures and binds and covers the books. It’s a team effort.

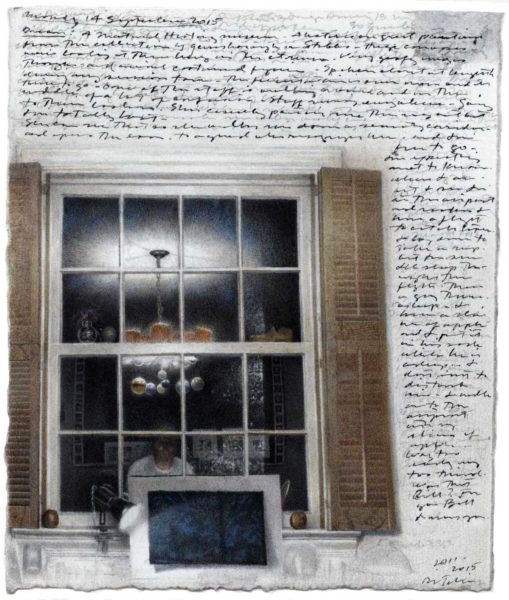

Self-Portrait with Blue Drawing, 5 1/8 x 5 1/4″ watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on Fabriano paper, 2015

LG: I understand that you use a Rapidograph pen to make dream notions in your journal, what effect does this activity have on your drawings? How does the writing relate to the drawings, especially since much of it seems unreadable?

Early on, I realized that I could compress more into my books with small writing – I’m a natural to the miniature. Using a very fine point Rapidograph ink pen, I developed a note hand that allowed me to write quickly and sustain a degree of privacy – I’m usually the only one that can read the script. I also imagined writing in tiny regimented rows of calligraphic gesture could be a good training exercise for my eye, hand, and fingers. As far as the connection between images and dreams in my books, they do not intentionally correspond. I’m writing down dreams in my notebooks, offering an outlet for my subconscious at the same time I’m sketching the world, filtering images through the visual pathways of my subconscious. I see the two paths as parallel recordings of my life. Regarding my independent drawings outside the books containing writing, these are generally waking notes coming out of dream states as I start my daily painting sessions. Writing mingles with image in a palimpsest of erasures and overlays; a record of sessions and days and years. Text and pentimenti are often subsumed as the drawing progresses.

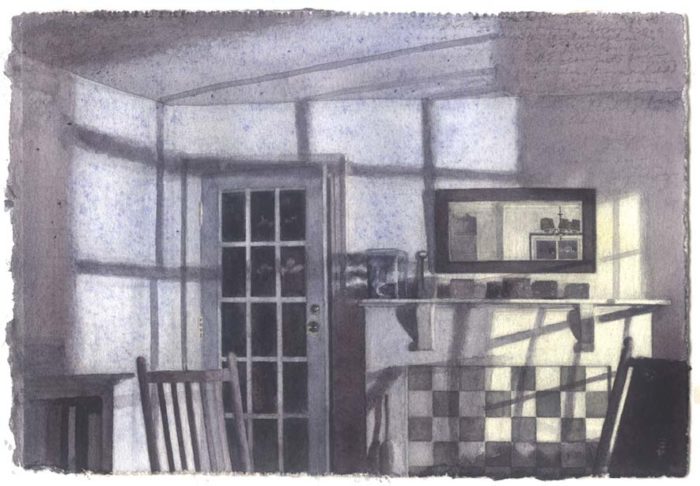

First Light, Work In Progress 5 7/8 x 10 1/2″ watercolor and graphite on Fabriano paper, First state. 2012

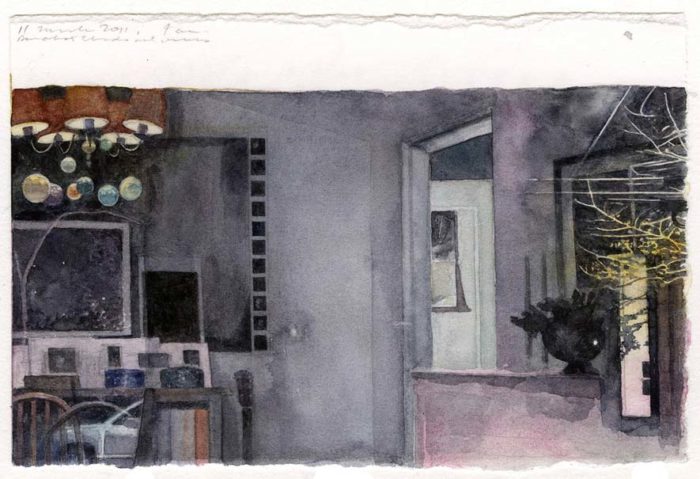

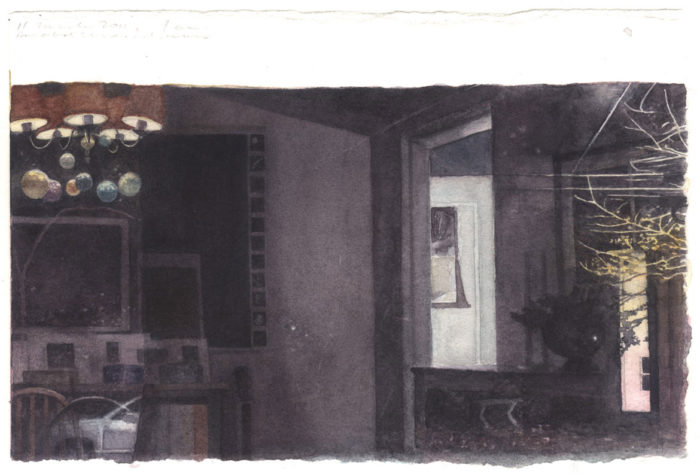

Reflection: 11 March 2011, Work In Progress 4 x 6″ watercolor and graphite on Fabriano paper, First state.

Reflection: 11 March 2011, 4 x 6″ watercolor, conte crayon, and graphite on Fabriano paper, Second state.

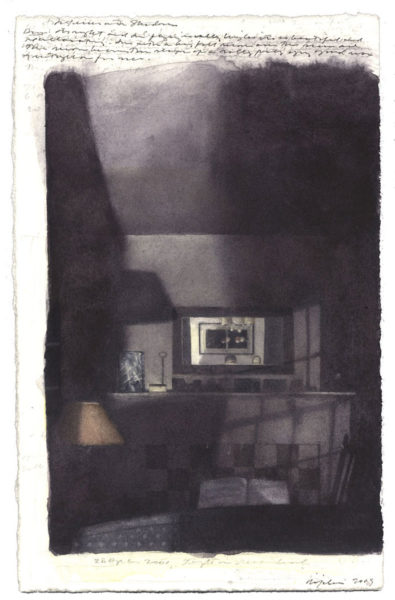

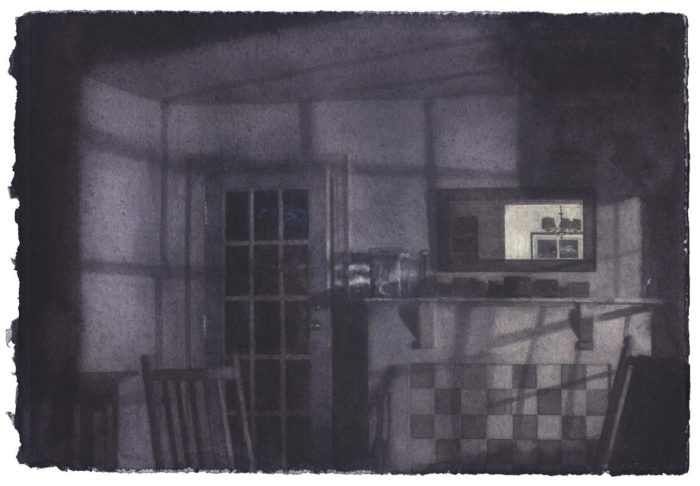

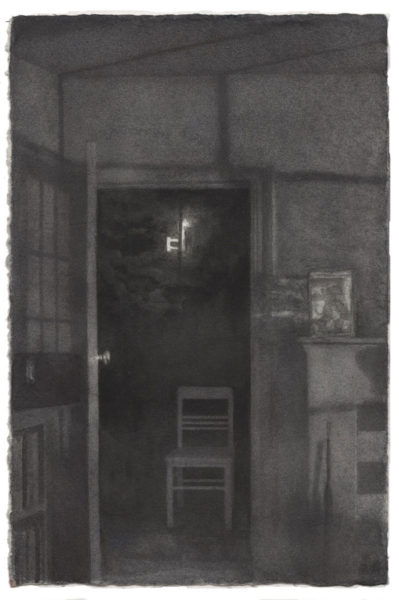

Interior with Shadows, 4 x 6″ watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite on Fabriano paper, Fourth state. 2009

LG: Many of your sketchbooks show loose alla prima watercolor drawings and other works are done over long periods of time, how much do you balance working on looser, quickly made work and work done over long periods of time? Or is it all just different levels of completion and is really the same process?

CR: The journal sketches are generally made quickly, a la prima, responding to the impulse. Time progresses in a linear fashion as I move through the book(s) and so I rarely go back to rework something I painted earlier; I’d rather rethink the idea again on another page. Drawings executed outside of the books are usually more extended campaigns; while loose washes can be integrated into them, they tend to be built up with a range of techniques over longer periods and numerous sessions. These independent drawings are culminations, presenting arrivals that obscure layers underneath. Both journal and independent drawing contain chronologies of thought and action. And both approaches are equally important and I select the method that I think will be most successful to accomplish the task at hand.

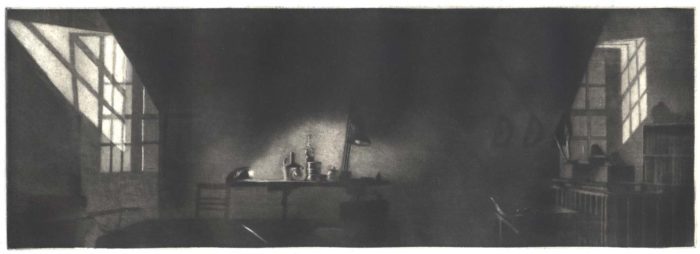

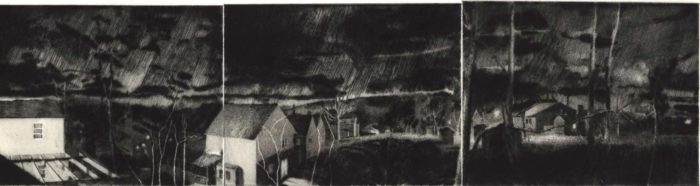

Interior with Still Life, mezzotint on chine collé on Rives BFK paper, The hand-rocked mezzotint plate for this work was scraped and burnished over a period of eight years. 4 1/8 x 12, 1996 – 2004

LG: You are a printmaker as well and have used your drawings as a source for a variety of printmaking techniques such as etching, mezzotint, aquatint and drypoint. How has printmaking influenced your drawing and vice-versa?

CR: Regarding the influence of printmaking on my drawings, I love intaglio because working on a plate is excavation in microscopic relief. I’ve come to see my drawings as relief surfaces in the same way. Everything from the soft texture of my hot press paper, to the gentle undulation of the sheet, to the ragged deckle edges, to the watercolor layers I apply and then subtract; it’s very much the way I view the harder, but malleable topography of the copper plates I work as a printing matrix. But beyond that, printmaking has affected a primary attitude shift; I’m more open to accident. All the preparation in the world will not divine what is going to come out on the other end of the printing press. The collaborative effort and accident inherent in printmaking wrests degrees of control from an artist. That’s been good for me. Since I’ve been making prints, I’m far more inclined to review the results of a drawing campaign and question, “how can I use this” rather than call it a failure when compared to some image I’m nursing in my mind’s eye. Letting go of control can cultivate possibilities. As far as my drawing influencing my prints, well, I’ve come to see printmaking as a path for my drawn images to find new life as a print. My prints are always based on my drawings and I enjoy seeing what print processes can do to reconfigure and transform an earlier image.

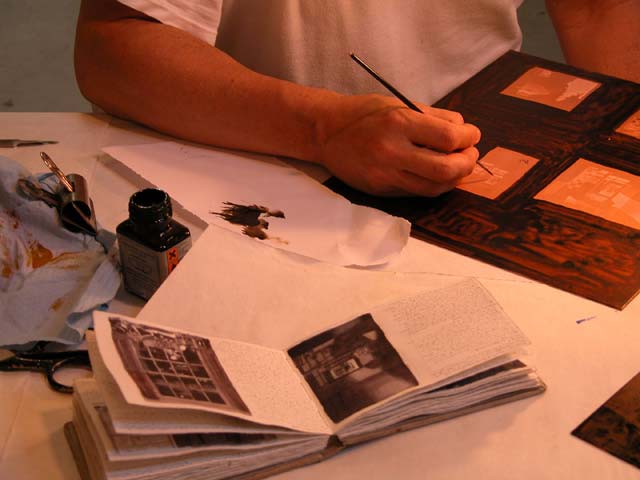

Photograph of the artist working on an aquatint plate, At Center Street Studio, Milton, Ma. The artist’s current journal is open in the foreground and is being used as a source for images and texts.

Photograph of James Stroud and the artist, preparing to paint spitbite on a printing plate, At work on the Accordion Fold Print project at Center Street Studio workshop, Milton, Massachusetts. Photograph by Janine Wong.

LG: Do you have your own printmaking studio?

CR: No, I’ve had the good fortune to work with printer/publisher Jim Stroud of Center Street Studio in Milton, Massachusetts. When I want to work on etchings and aquatints, I go to see Jim. He has the setup and the printing skill. I could spend my life trying to acquire Jim’s level of expertise and never arrive. Also, he never lets me do the same thing twice and he always offers various options about ways to proceed and imaginative solutions to problems that pop up. I do have a mezzotint table at home where I rock and scrape my plates, but all of that is done without acid. I mail the plates to Jim to proof when we want to see where I am with a print.

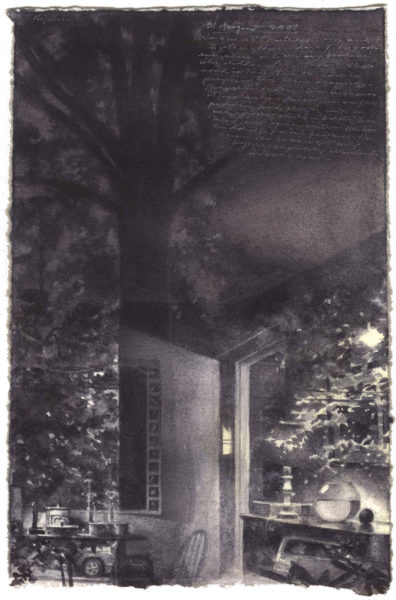

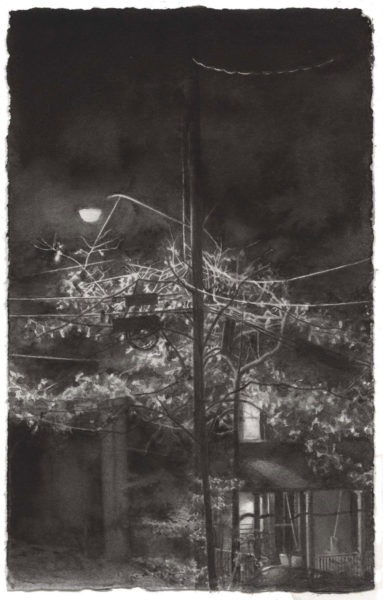

Summer Night with Interior, watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on Fabriano paper 6 3/8 x 4 1/2″ 2007

LG: I believe you said in your lecture that “great art starts with dissatisfaction” can you say something about how that has played out for you?

CR: Who thinks they’ve achieved an unassailable level in their artistic practice? I know I haven’t and within my own dissatisfaction is a drive to continue to up the bar. I’m playing a game, very serious and high-minded, yet also a loose and exuberant game, and I expect it to add up to a good, exciting time, an extraordinary stretch of my abilities, and hopefully an overall arc of improvement, and perhaps, at its best, reach a kind of visual poetry.

LG: Where do you get such enormous tenacity to stay with a drawing for such long periods of time?

CR: For one thing, I work on multiple drawings at the same time. It’s a strategy I’ve used for many years. I rarely let myself work on the same drawing more than two or three sessions in a row. By shifting from one drawing to the next, the whole process has a harder time of stagnating. Also, the method encourages the bringing back of discoveries made on one drawing to reinvigorate other drawings. When I say I’ve worked on a drawing for a dozen years it means I’ve worked it intermittently across that period. I don’t like to be in a hurry to finish a piece. It feels disrespectful to the drawing and it diminishes the organic nature of my process. What I most enjoy is finding an unfinished drawing, lost for years in some pile, presenting itself like some alien being that I don’t even remember. The best is when I suddenly realize that it is the perfect next step. But beyond strategies and process, my commitment is essentially about love. Love of what I’m doing and love of the experiences that are unfolding in my world. My goal is to stare as deep as I can into this mystery called life. The drawings and prints are what I return with. What an amazing privilege and joy to live my life this way. Tenacity comes easy.

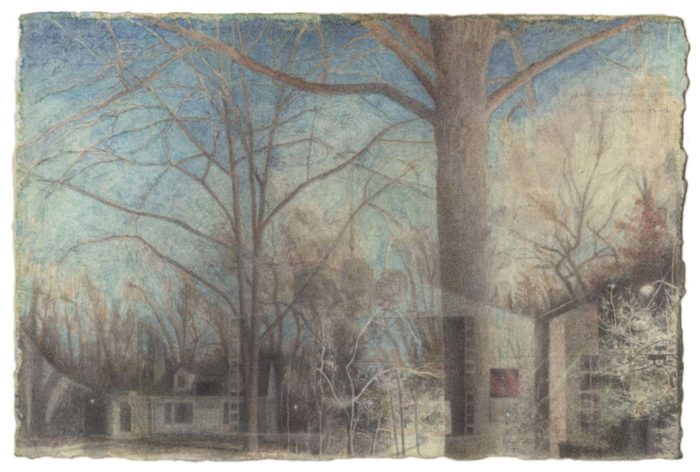

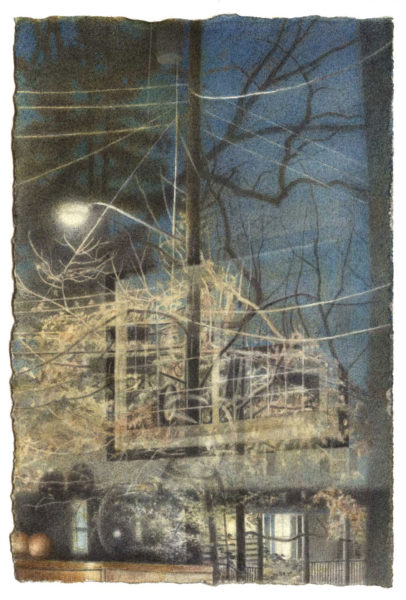

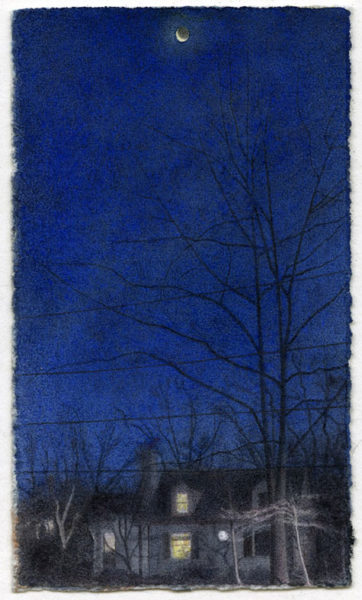

Home 3, Work In Progress 5 7/8 x 3 5/8″

watercolor and graphite on Fabriano paper, First state. 5 7/8 x 3 5/8″

January 18, 2013

Reflection with Astronomical Chart, Work In Progress

6 x 4″ watercolor, gouache, and graphite on Fabriano paper, Begun 16 October 2013. First state.

LG: Some painters today have difficulty with so many distractions like Facebook, text messaging, and other aspects of our ADD culture. They might want to work on sustained projects but have great difficulties focusing? What suggestions might you offer for getting into the right mental state for painting?

CR: I would suggest trying to work with one’s body rhythm by determining one’s best time of day to create. Are you a morning person or an evening person? No one is going to have a perfect situation, but one must carve out time and a place to work and respect that space. For my part, I can’t wait to roll out of bed and into my private world, no alarm clock needed. Secondly, I personally like the physical qualities of my journal. I write and draw in it, it is immediate and it minimizes the electronic distractions. I have no beef with journals on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, blogs, or websites. Especially, if it is your art form. But if it is an accessory or a means of promotion, well, my experience was that I became sidetracked. I actually integrated a blog into my web site for a number of years, eventually realizing the huge drain it placed on my creative energies. So I stepped back. Now it’s just a web site which I tend every few weeks www.charlesritchie.com (though I do retain the earlier blog entries that I had uploaded to the site.) I also keep up with email but try to corral it in a place distinct from where I am doing my art. The digital world is a blessing and a curse. Love it, but limit it, is the policy that works for me. Put the big energy in the journal and the drawings and prints.

A solo exhibition of the artist drawings is currently being planned for 2017 at BravinLee programs, New York.

Thank you for posting this interview. I first encountered Charles Ritchie’s artwork in an exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art in 2004 and have followed his art ever since via his website and exhibition catalogues. His images are beautiful, capturing the quiet quotidian of his perceptions and process. Mr. Ritchie is a very talented, thoughtful and disciplined artist. His process results in an art that is indeed “visual poetry.”

an exemplary artist. Have loved his work and spirit for quite a while. Thanks for the good read Larry.