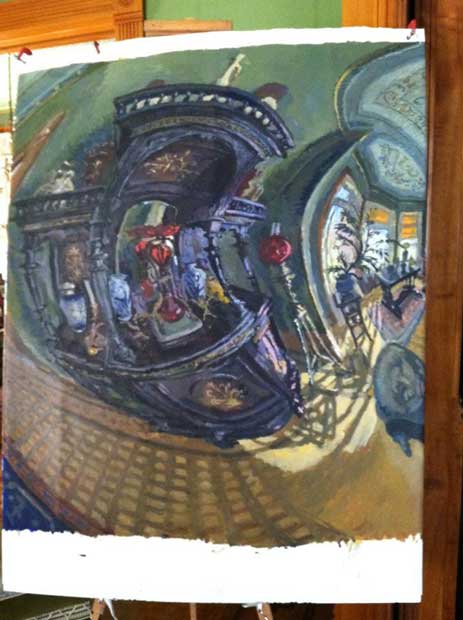

Matthew Lopas, Detail from Miller House

Matthew Lopas recently contacted me on facebook to let me know of the current show of his panoromic paintings at the Narthex Gallery at Saint Peter’s Church in New York City. The show runs from May 17th to June 19th. I was intrigued by his process of making panoramic interiors and emailed him some questions about his process and thoughts behind painting the expanded view. Matthew Lopes teaches painting at the Hendrix College in Arkansas. He recieved his MFA from the Yale School of Art in 1995 and his B.F.A from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago,1991 He is represented by the Ober Gallery in Kent, Ct.

Larry Groff: What interests you most about painting panoramas – what is your attraction to painting an expanded field of view?

Matthew Lopas: The conventional viewfinder produces wonderful compositions, but it is always at a distance from the viewer. I find its frame limiting and alienating. In fact, our field of vision is much wider than the perspectival conventions originating in the Renaissance. My images are truer to the actual experience of what it is like to be in the world rather than to look at the world. A radically expanded field of view enables a profound intimacy with the real act of looking and creates an unmediated gaze of empathic seeing. This fills me with wonder, joy, and catharsis.

Several years ago I started a painting outside on my deck. I stood very close to the outside wall of my house and started to paint a panorama. As I proceeded I realized that the house “distorted” into a radically curved shape. I had never seen or done this. It made me queasy. The composition seemed unbalanced. So I moved further away from the house so the curves were minimized. The image appeared more conventionally level and plumb. The painting turned out well, but it is not nearly as exciting as the work I have done that does not fear reality as it is actually seen. The distortions seen in curvilinear space can be upsetting to a mind dominated by conventional perspectival paradigms. It took me a little while before I was able to leave conventional perspective behind.

The understanding of how we perceive reality that the viewfinder creates is false. It has helped create many great works of art, but it can act like a set of horse blinders. A Hopper room feels as if it is a million miles away, and if you could walk into one of his images, you would never escape. A Vermeer is so silent and filled with a spiritual light that to enter it would be sacrilege. A Leland Bell is so level and plumb that it represents more of a frieze than an actual visual experience of space. These are great painters, but I seek to paint a world that is alive with the living gaze of a human who moves, breaths, and loves to look and feel

I first began thinking of creating images that more closely reflect the way we truly see while studying Van Gogh’s Room at Arles. I noticed how much closer the frame of his image was to him than other painters that I emulated, such as Vermeer or Hopper. I moved to a deeper level of engagement in this issue when I began looking at panoramic images.

Miller House, 56″x102″, 2012-13, oil (private collection)

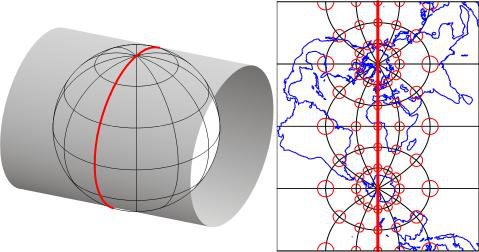

Although tableaus have been around since the Middle Ages, the conventional panorama was invented by Robert Barker in 1787. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclorama) Barker actually patented his design of a 360 degree, cylindrical, building sized panoramic painting called cycloramas. I go beyond these historic panoramas, however, by traveling at least 360 in the vertical, as well as the horizontal, directions. In essence I create “global panoramas”. After research, I realized my artistic aims had more in common with 2d map projections of the globe than viewfinder based images. My study of these map projections gave me a deeper understanding of what I was trying to do and pushed my work to another level.

Maps of the globe are diverse, and surprisingly dynamic in their application. The various map projections of the globe are generated with mathematical rigor but also distort and tessellate with creative choice. Most flat maps of our globe have the North Pole at the “top” of our planet and a very distorted Greenland, which is a construction based on social convention. A cylindrical projection can just as easily have a vertical equator as a horizontal one… a map of our world constructed with a different equator produces a totally different set of distortions.

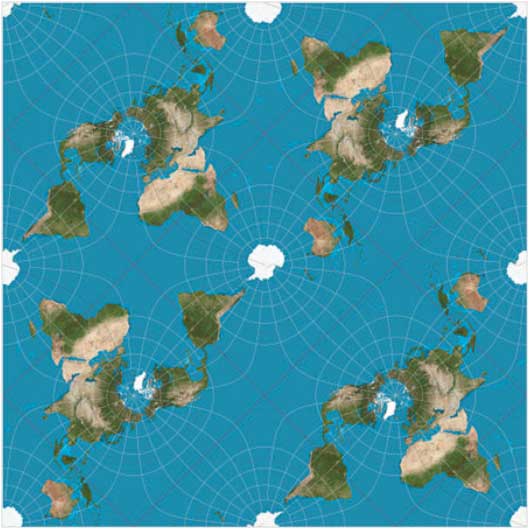

The Pierce quincuncial projection shows how a map (or painting) can tessellate infinitely in all directions. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peirce_quincuncial_projection) When studying these maps, I realized I could tessellate space within my painting. I could record the shift in the direction of my gaze around the surrounding space and seamlessly paint the same object in the same actual location in different places within the same painting. This understanding guided my eye as I measured the space within the work. It led me to arrive at unexpected compositions. If you look at my most recent piece, Miller House, it may be surprising to learn that there is actually only one red light in the room. I spun around more than once so I could paint it twice at different times. I was excited by the relationship I saw to the medieval practice of incorporating events from different times in the same image. The compression of narrative time in a rigorously measured painting allows for a deeper engagement with the space depicted, for example, beautiful light from different moments can be painted in the same picture.

Baker House, 50″x60″, oil, 2012

LG: You started a Facebook group Painting 360 – Contemporary Variations of the Painted Panorama features a diverse range of contemporary painters who embrace some aspect of panoramic painting. Rackstraw Downes is likely one of the most recognized names and embraced painting expanded views early on. Who do you consider the most important painters of this genre and who are your most important influences and inspirations?

ML: I started Painting 360 to network with artists interested in this topic. I envision one day creating a travelling group show or a conference of some sort.

Downes has always been one of my favorite painters. He helped open up the possibility of doing something besides painting only what was directly in front of me. The wording of the title of his famous article Turning the Head in Empirical Space (in the book, Rackstraw Downes – ed.) is a lesson in and of itself. I am very interested in what happens when I allow myself to turn my head as I paint. Certain lines in nature, for example the side of a building, are, in fact, straight, yet when rigorously measured they curve visually. Painting as you turn your head increases this curve. The subtle and interesting question posed to me by Downes’ work is: What happens if this visual curve is painted as a straight line? Realizing that other elements must “distort” to compensate (much as Greenland triples in size on a flat map) gave me the creative freedom to rigorously distort based on intuitively inspired measurement. The basic idea is, if you stretch one thing in an image, it drags other things along with it.

The next artists build upon the historic cycloramic genre by working in the global panoramic mode. The artist Jacqueline Lima is a New York painter of panospheres. These are paintings actually on spheres. Onecan capture the entire field of view (360 in all directions) with absolutely no distortion using this method. Lima paints gorgeous spherical landscapes and cityscapes. She is also an innovative thinker about curvilinear space. I invited Lima to visit Hendrix College last year. She gave an incredible demonstration on how to actually mark all the longitude and latitude lines in a room as preparation for painting a panosphere. She showed that setting up a sphereical viewfinder is as really pretty simple.

Artists Rorik Smith and Marcia Clark are engaging practitioners of the global panoramic genre. They can be seen on Painting 360. Smith resides in North Wales and has a great understanding of map projections asthey relate to representational painting. We have traded many emails regarding the creative possibilities of the form. Clark, a New York painter, has made many innovative shaped paintings of the entire field of view. She clearly points out the fact that we do not experience the world mediated by a rectangle.

Living Room with Sculpture, oil on canvas, 37″ x 62″, 2009

LG: Who do you consider the most important painters of this genre?

ML: The most interesting contemporary practitioners of the cycloramic form are Sanford Wurmfeld and Yadegar Asisi. Wurmfeld is a New York painter who makes huge abstract cycloramas that have stunningly immersive color (series of lectures by him on youTube). He builds on the work of Albers. He currently has a retrospective at Hunter College. Asisi is a German digital painter who does formally conventional cycloramas only on a gigantic scale. They can be many stories tall. Historically cycloramas often have nationalistic agendas. Asisi brings a more critical eye to bear. Both are interesting cyclorama painters, but haven’t had much direct influence on me.

Sanford Wurmfeld and Yadegar Asisi, Panometer, Asisi Factory: Dresden 1756

LG: and who are your most important influences and inspirations?

ML: I have already mentioned Van Gogh, Vermeer, and Hopper. I love the quiet firelight in De La Tour as well. For years I did paintings of fire lit interiors. Pollock is my definition of good paint handling. He moves paint with total fluidity. I love to look at painting, but I no longer feel the need to search for artists to take something from. Any great painting, no matter the style or time it was made, is an inspiration. I just showed my students some Soutine images. Wow. Great.

LG: What is the relation of your work to panoramic photography?

ML: Panoramic photography has existed since the dawn of photography and is currently everywhere. You see it in webpages for hotels. You can stitch panoramas together on your phone. You can turn videos that pan in panoramic stills. 360 degree virtual spaces can be seen on Google maps. First person shooter video games move the player through a 360 degree virtual space. What is interesting about this is that people do not seem to understand that the conceptual framework for this is not based on some computer magic, but rather on direct observation of the entire field of vision as we see it. Photographers, mapmakers, mathematicians, game designers all know that one can take all (or nearly all) the visual information that can be seen from a single point and stretch it out on a flat surface or put it inside or on a real or virtual globe.

My relation to these mechanical means of mapping the 360 degrees of perception is the same as any perceptual painter’s relation to conventional photography. Photography lacks the materiality of paint. Photography does not allow for the movement of the arm as is makes beautiful measured marks. Composition in photography is based on a design that eye sees, not the movement of the arm. Photography has less to do with the body in this way. Photography can distort space with wonderful accuracy, but not with the kind of empathy that a painting can. A painter has to understand every detail that is painted. Photography shows all the irrelevant detail within its field of view. Paintings eliminate the clutter. I love photography. But it is not painting.

Pleven Epopee 1877 Panorama exterior from the 21st International Panorama Conference in Pleven, Bulgaria

Pleven Epopee 1877 Panorama interior. A 360 circular painting.

LG: You attended the 21st International Panorama Conference in Pleven, Bulgaria where speakers from all over the world discussed various aspects about panoramas. There are panoramic photos of the conference you took using an iPhone. Can you tell us something about what this was like?

ML: The IPC conferences (http://panoramapainting.com) are very interesting and have been an incredible learning experience for me. In Pleven we visited a Soviet style cyclorama that is a monument to Bulgarian independence from Turkey. It is a socialist realist image of an historic battle. The mayor of Pleven and the head of the national assembly welcomed us, so the whole thing was a little surreal to this American. Papers were given on topics ranging from the history of lost cycloramas, media history, virtual reality, and contemporary cycloramas in the United States, Turkey, and China. I gave a talk titled “Reinventing the Panorama through Perceptual Painting”.

Attendees at the conference had previously understood the panorama from academic, historic, or photographic perspectives. They had never seen it from inside the act of looking and painting. In my talk I told the story of how I moved from viewfinder based images to the global panorama, and shared the moment in the process of painting Ward House; I realized I could turn the painting over, turn myself around, and keep working with perceptual ease. The discussion that ensued concerned the ability to actually see the world from a global panoramic point of view. They pointed out many types of lenses and tools that had been historically used to measure this phenomenon, which further deepened my understanding of what I was up to.

The first conference I went to was at the Gettysburg cyclorama in Pennsylvania in 2011. I learned that cycloramas were travelling building sized cylindrical paintings that were the movies of their day. Similarly to many Hudson River school paintings, they functioned as entertainment and propaganda. Cycloramas were incredibly popular. The paintings are usually at least two stories tall, viewed from a large central raised platform, illuminated by natural light, and some had a diorama element in the foreground. If the diorama element is right, the transition to the painted surface is seamless and akin to the transition from low to high relief in a good bas-relief. The sense of space created in a well done cyclorama is nothing short of spectacular. Gettysburg is a must see for any painter. There is definitely a kitsch element to the cycloramas that I have seen. Gettysburg, for example, has a light show designed to give the effect time passing. And Pleven has the stolid seriousness typical of socialist realism. But the experience of immersion they offer is truly mesmerizing.

Sconces, oil on canvas, 35″ x 65″, 2009

LG: Your painting seems to embrace rather than suppress the parallax distortions seen in some camera panoramic views or curved mirror and fisheye lens. You use these distortions for expressive and compositional intent. Can you tell us something about how you go about creating the drawing for your paintings? I know you paint from observation but do you use a photographic means for working out the drawing and mapping how you will maneuver through the space? Or do you work it all out through direct observation using a viewfinder?

ML: I embrace the “distortions” that occur naturally with a wide field of view; the similarity to images produced by a camera lens is incidental. I discovered the bending of the visual field using the same tools that all perceptual painters use – measuring lines, locations, and sizes with my thumb or paintbrush. The only unconventional thing I do is to discard the edges of a viewfinder in favor of a 360-degree view. No lenses beyond the one in the eye are used. The distortions seen are as “real” and as visible as the more commonly understood distortions of conventional perspective. Conventional perspective depicts objects that are farther away as smaller. This is a distortion of their true size.

One way I show my students curvilinear space is to do a very small drawing of the easel in front of them in the middle of a large sheet of paper. When they then build the drawing out in all directions their eyes and pencils are confronted with visual reality unmediated by a viewfinder.

I start a painting in a similar way. I use a very large piece of upstretched canvass that is rolled up on either side and clipped to a four by four foot board. I set up on site and paint something very small, roughly in the middle, based on visual interest and the direction I want to travel in the space. Arriving at the point where I could be comfortable with the resulting distortions involve a series of perceptualdiscoveries and giving up the grip of the all-dominating grid. My heroes: Vermeer, Vuillard, Mondrian, Balthus, Hopper, and Leland Bell; based their images on the level and plum world of Cartesian space. I had to jettison the compositional strategies they taught me. I now think of composition in terms of how the eye moves over the surface and through the space, rather than how flat shapes can form a spatially active design within a rectangle. Conventional “balance” is discarded. I love the way elements can be distorted and yet still remain consistent to actual measurement.

painting of Miller House video

Work in Progress

LG: Your paintings tend to be quite large for working onsite. This must pose difficulty when painting in people’s homes, standing on their stairway, etc. How do you deal with seeing the motif and your painting at the same time? How do you keep from getting wet paint on their nice carpets and expensive upholstery! Looking at your easel it seems like you have some sort of scrolling mechanism to unfurl the area of the painting needed to be worked on, how exactly does this work? How do you see parts of the painting in relation to each other when covered up like this? Does this create difficulties with unifying the painting when you’re unable to see the painting as a whole?

ML: Painting like this presents many logistical challenges. Getting an easel to stand up on a staircase took a bit of thinking through but an adjustable tripod easel solved the problem. I use drop cloths that I fold to fit perfectly to the angle I am working on for the day. I cover things that might get paint splashed on them. I uncover them only for as long as I need to. I was a house painter for a short time after grad school and got used to never touching anything because I was sure to get paint on it. Despite training myself to be finicky as I move though a space, years of practice enable me to maintain the freedom to enjoy the sheer pleasure of loosely moving paint on canvas.

My paintings are often too big to be fully unrolled in the spot I am working. A six-foot painting simply will not fit on a staircase. Thus my process involves working on the image in separate parts as I turn and unroll and reroll the canvas. I overlap areas as I work so that the piece does not degrade into segregated parts. Most importantly, I do not plan the composition with a viewfinder based thumbnail sketch.Instead, I take risks as I let the image suggest distortions and tessellations.

Periodically in the process I put the piece up on a big wall and look at it. This helps me to know where I am going as I work from life later. In the end I work it as a whole from memory and the information within the image itself. It is said that the first four lines of any painting are the edges. But they can also be the last four lines. I determine the edges of the painting as I work and stretch it when it is done. This makes the process flexible and open ended. This methodology allows me to avoid compositions constructed by synthesizing historical precedents and create compositions that don’t conform to conventional strategies

LG: Why interiors and not outdoors? What makes you choose these particular rooms and views to paint?

ML: I have painted many landscapes, especially in Chicago, my home town. Landscapes, however, can’t be inhabited in the same way as interiors are. Paintings of interior spaces embody a human presence and depict places that viewers project themselves into, or imagine others moving around inside. Landscape paintings can make the human presence seem small. Nevertheless, I do look for interiors that have some of the qualities of landscapes. I love the clouds in a landscape. So I try to find an interior that has something you can look up at. I look for spaces that are complex and have many facets within them. I look for a room with doors, and windows with views, or passages into other places. This helps me create images that embody the multi-faceted and often dichotomous nature of our internal lives.

I have painted many pictures of my home in Arkansas, but when my father died in 2007, I was moved to go back to his house and paint my childhood home. The experience was a creative bomb. I worked with an emotional intensity and intimacy with the space that was unprecedented for me. After that I searched for places that have intense memory, even if it is someone else’s memories. They must have a human presence that I can understand and empathize with.

LG: Do you think painting on site influences how you paint?

ML: There is simply nothing like working from direct observation. The world presents an organic visual complexity, almost a chaos, which one simply cannot invent. If you look hard enough, you will find infinite colors in a simple white wall. Looking at nature is continually surprising and sustaining.

I cannot paint just anywhere that is visually interesting. Public places have visual complexity that could theoretically make an absorbing image, but they don’t have the sense of personal individual memory that interests me. I need to feel a real connection with the place I paint. That is why I search for places that remind me of the ornate home I grew up in. I search for a place that represents a certain sense of longing for something lost, for something I can never go back to, like my childhood home, a sense of mortality.

In his Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard calls our first house a “nest for the imagination.” The house one grows up in forms the structure for the way spaces should be. All other places are measured against your original house. I try to tap in to that kind of profound relationship to the place I paint. I look for places that I feel I was born knowing.

Foyer and Staircase, 44″ x 63″, 2009

LG: Would you paint differently if you were working in the privacy of your own studio where you also didn’t have to worry about getting in the way or time constraints?

ML: I always work in places where people welcome me and I have no time constraints. Without that basic freedom I cannot work.

Formerly I made paintings of spaces I constructed in my studio. I’ve also done numerous paintings of totally invented places. Neither was satisfying to me. A constructed or imagined space always seems artificial or forced. The specific relations between objects have no chaos or randomness. The painting intervals become static. The images tend to be simple and dull.

LG: There is a fast, loose and expressive quality to your brushwork that sometimes seems to run contrary to the difficult drawing challenges you set for yourself. Why do you choose this approach as opposed to a slower, more precise approach seen in someone like Rackstraw Downes?

ML: Well, of course, the precision of painting is not in a neat brushstroke, but rather in the exact relationships between strokes. Knowing this is one thing, but making paintings based on it is an entirely different matter. Right out of Yale I made paintings with very thick, loose, wet masses of paint. The luscious paint dominated the simple compositions. Needing more precision, I began to do meticulously rendered large drawings that served as the basis for precise glazed studio paintings. They became mannered as I lost the direct input of working from observation. It has taken years of intense work to get to the point where I can move paint with freedom and still maintain drawing accuracy.

I paint what I love to look at, and try to be at the absolute edge of my skills and conceptual understanding. The love of what I do, combined with the sheer difficulty and challenge of what I paint, creates urgency in the brush. My brushwork is a result the mix of formal ambition and intense visual desire.

LG: Extreme expanded views, especially with dramatic curvilinear distortions or fragmentation of the view runs contrary to the quiet divisions of space and balance one sees in more classically composed paintings where horizontal and vertical divisions and how they relate to the painting edges are critical. Do you think expanded views risks interfering with the quiet visual contemplation of light, color and geometry as might be seen with Vuillard’s interiors?

ML:

The “distortions” do risk becoming distracting mannerisms. I seek to balance that danger with beautiful paint and by providing opportunities for reverie in many moments of quiet contemplation within the image. The detail shots show these small moments a bit better. I love Vuillard and hope the meditative moments in my pictures are reminiscent of his.

The light within the paintings is delicate and ephemeral like Vuillard. The image gently envelops the viewer as the eye wanders through the piece. I personally remember the paintings in a floating dream state.

I love classical geometry and compositional strategies such as the golden mean, the repoussoir, or the rule of thirds, nevertheless, I seek a non-programmatic organic structure that can be more surprising and thus more stimulating. The golden-mean spiral in a nautilus shell, and the exotic labyrinthine fractals seen in a lightning strike are both great! But I prefer to paint the more unexpected geometry.

LG: What are your most important concerns with regard to composition in your work? What do you want the viewer to experience? ?

ML: I want the viewer to empathize with human quality of the space, to feel the condition of being in one place and letting the imagination wander through memory or reverie to another place. My compositions embody the full point of view of an observer, allowing them to wander off the edges of the painting. The viewer can see how a space is actually seen and felt by two eyes in a body not mediated by a viewfinder.

We are more than just a single idea or thought so cannot be represented entirely by a single simple place. We are an active labyrinth of memory, imagination, desire, and adaptive intelligence. I want my pictures to reflect this.

fascinating interview with lots of food for thought re: types of vision…thank you larry!

Having visited Matthew in the houses he paints, I became aware of just how much our brains rationally piece these complex spaces together into something we can walk into and about. But vision without the schema reveals how much our own presence within a room is not so much a given as it is transparent, amorphous and ghostlike. We inhabit the space not just as an observer but as a participant. Ghosts indeed.

you should check the metapanoramas project by Raul Moyado , 360 view paintings using the google street view technology

moya.do/english/google-street-view-paintings.html