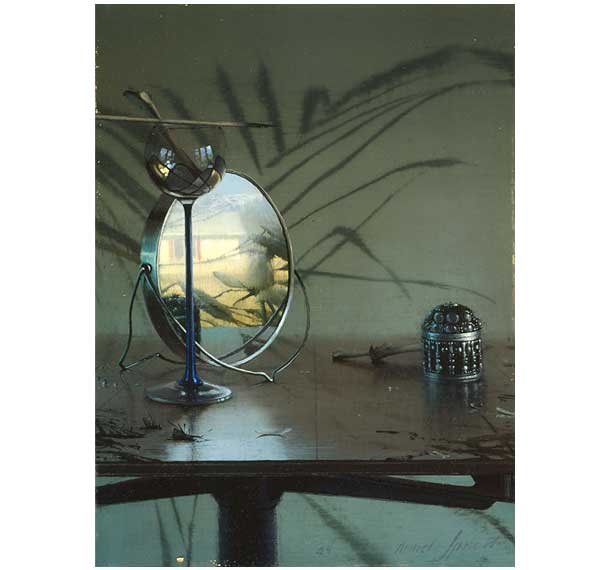

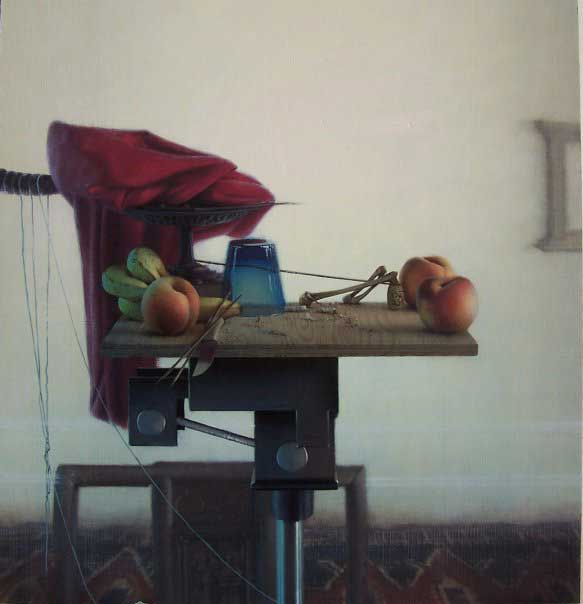

Daniel Sprick , Still Life & Mirror, , Oil on Board, 12 x 9 inches

click here for a larger view

Liminal Spaces: A Conversation with Daniel Sprick

by Elana Hagler

As I pull up in my car, the first thing I notice is how out of place my destination seems in this typical, urban Denver neighborhood. Nestled between the larger streets with their mostly brick and some stucco, one or two-story mismatched shop fronts, gas stations, bars and parking lots, lie smaller tree-lined streets with terra cotta colored, unmistakably Denver bungalows and some small businesses interspersed with three or four story apartment buildings. And towering over all this are two gleaming, contemporary sky-scrapers that seem to have lost their way from the actual downtown (a mile or so to the west) and, weary and bewildered in their unfamiliar environs, decided to plop themselves down for some much needed R and R on the very edge of massive and green City Park. I enter the near building, filled with anticipation for my visit with the painter Daniel Sprick.

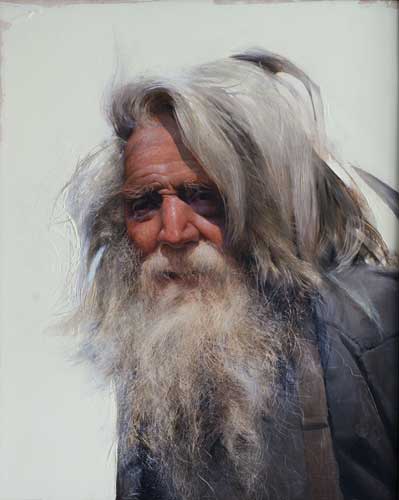

An elderly concierge informs me that Daniel is expecting me and ushers me through the lobby to the elevator, where he leans in to give me access to the right floor. Daniel’s door is open and he calls my name in greeting as I peer inside. Daniel is casually dressed and soft-spoken as he welcomes me and leads me down a long corridor into the heart of the space, a large, light room attached to an open kitchen, illuminated by a tremendous wall of glass overlooking the trees and open fields of City Park. The walls are filled with a broad sampling of his striking, highly resolved and animated portraits, juxtaposed against angular and fierce aboriginal masks.

Daniel was kind enough to offer me a critique of some of my most recent paintings, in addition to agreeing to do this interview with me, so I’ll first include some of his advice pertaining to my work, which I feel might also be more universally helpful. Before giving any specific advice, Daniel clarifies where it’s all coming from: “Essentially, I can only say what I would do if I were painting. So, that’s just a caveat about the way I critique work. Because what I would do is consistent with my biases.”

Daniel Sprick in his Studio – Photo by Elana Hagler

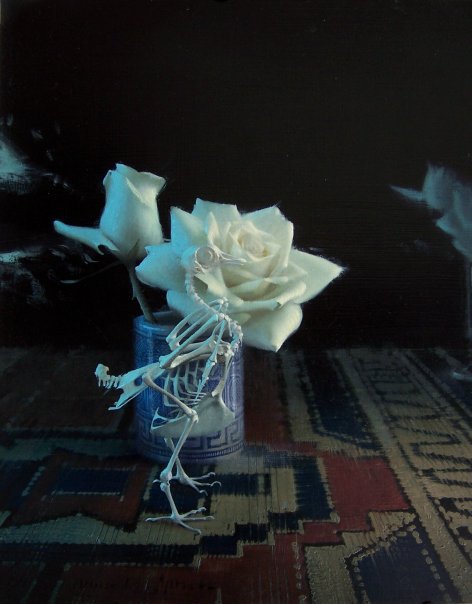

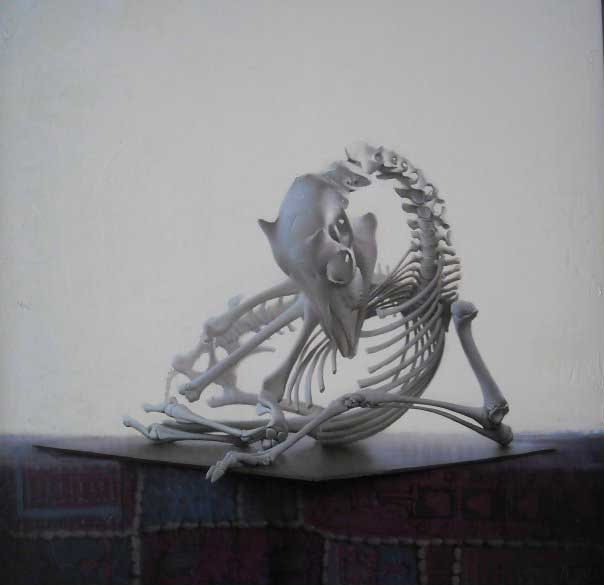

“Bird Skeleton” Oil & Board 12″ x 9″ – 2004

I can completely understand where he’s coming from with this caveat. Giving and receiving criticism can be a delicate matter. I’ve been on both ends of this process for a number of years now, and I know that when a painter of great reputation and/or strong convictions is giving a critique, there can be a great temptation to read it as dogma, and then some students may completely adopt this “dogma” and before long start to make little copy-cat paintings, and some students may see this as an imposition of someone else’s preferences over their own in a totalitarian sort of way, and may feel very affronted. Because of these possibilities, I’ve seen instructors who are so timid about asserting any formal preferences whatsoever that practically nothing at all is said during the critique. Having been around artists long enough, I have often encountered the bullshit artist who is beyond brilliant at tying long strings of philosophical-sounding words together that remarkably add up to diddly-squat. I maintain that we most often choose (when the choice is indeed up to us) to learn from people whose biases in some way speak to us, and as long as we’re not going to either worship or immediately disregard their advice, we might actually grow from it! As Daniel said, “Style is nothing more than a collection of habits.” I think it’s through the process of understanding other people’s biases and then seeing where we stand in relation to them, that we come more and more to grow into ourselves. Well, that and somehow surviving while deeply experiencing the rollercoaster that is life.

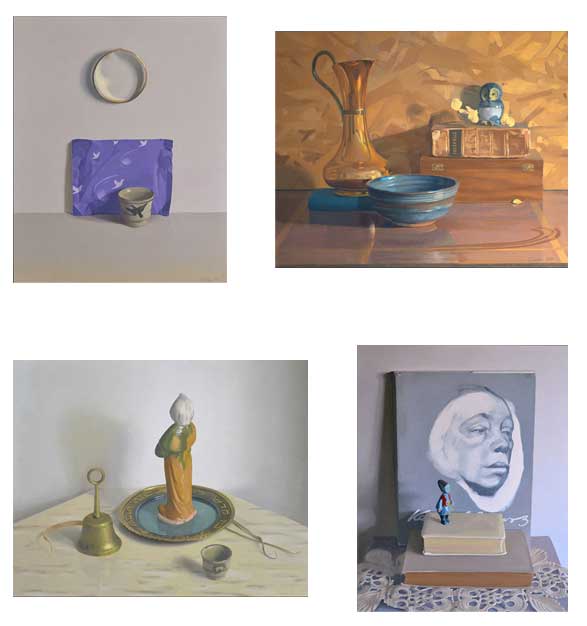

Elana Hagler’s Paintings being critiqued by Daniel Sprick

My latest paintings have tended to be more in the middle value ranges, and Daniel suggested, “Somewhere in the painting I would want to see a pure black out of the tube, a black hole. And conversely, I would want to see somewhere something almost pure white out of the tube. It’s what an artist told me once: use your whole palette. It was Wilson Hurley, who was a terrific landscape painter and he described that it doesn’t mean use everything you have equally, it may be just a square millimeter and, in fact, it doesn’t mean you always have to, because, if there’s a considerable amount of color you may not want to go all the way to white and black, because then it’s going to get garish. These are not with a huge chromatic range, and that’s why I think you can afford it.”

Pointing at a ceramic owl nestled between some aspen leaves, Daniel said, “I’m looking for a place to get it real bright, a highlight somewhere…something pure white. Oftentimes, I’ll put eggshells in the painting. People think, “What’s the symbolism of the egg? Birth, and all that kind of stuff. But the real reason is that I need something that’s bright white, or has a sharp edge, or both.” It’s funny how often people try to wrest out the deeper psychological and philosophical reasons behind any particular artistic decision when the artist may have felt it was the painterly equivalent of adding a pinch more salt.

I think the bit of advice that Daniel offered which I am taking the most to heart is, “The more you can diminish edges, the more effective the remaining ones will be.” He then proceeded to point out specific areas in my paintings where I could have softened or practically eradicated some edges, as well as some areas in his paintings where he had successfully done just that. Concerning the technique of applying this, Daniel said, “However you can accomplish it: with a glaze, scumble. I accomplish as much as possible with glazing because that’s what I call the low hanging fruit. It’s quick and easy and I try to accomplish things the easiest way first and then if that doesn’t work, I resort to more difficult methods.

At this point I put away my paintings, restarted the recording app on my iPhone, and got down to the real business at hand: peppering Daniel with my questions

Elana Hagler: What accomplishments of other painters, either historical or contemporary, inspire and move you the most?

Daniel Sprick: Well…I almost can’t separate myself from art history. So, just to start out with, some of my favorite artwork that has ever been done would be Northern Renaissance and Italian Renaissance. And it was done with such complete conviction, in addition to extraordinary technical quality. It’s done, I think, with a real palpable belief in the importance of the work. I refer to the 1400s, building up until Hans Holbein—which would be 1550, 1520, something like that. Also, Vermeer has been really interesting as a guide for me. Early on in my painting, I painted a lot of interiors and still-lifes. Now, I think that both Baroque painting and Renaissance painting are the standards for me in terms of depth and sincerity. They painted with no limit on the amount of labor it may take to accomplish. There’s also a lot of 19th century painting that I love, mostly be in the category of what you call the Naturalist School, which would be, for example, Jules Dupre and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret. Actually, quite a few artists whose names are really pretty obscure. In that category, there’s stuff that I like and that’s probably what I paint more like than anything else. My paintings tend to be more 19th century looking, even though I’m in love with the Renaissance. But, actually, I tend to think what I do, although it’s firmly rooted in the academic tradition dating back to the Renaissance, is of our time. And I’m comfortable with that, that it’s not just anachronistic, but that it’s attuned to our time. And not just the way that people or objects look now either, but the sensibility of our time. But of course those are rather intangible things that are a little bit hard to quantify.

EH: If you had to describe the sensibility of our time, how would you do that? In as far as it relates to your paintings…

DS: Can anyone? I don’t know…how would you describe it?

EH: Oh my gosh…I think there’s something about artifice that we’re so aware of.

DS: That could be good or bad.

EH: Yeah, I think people could use it however. But the awareness of the picture plane, the awareness of artificiality in painting, but also the sense of things having substance and other things being primarily surface and empty of substance, issues of irony and sincerity—I think these are the things that are very contemporary for me.

DS: Actually that question could be two things: What is contemporary in art and what is contemporary in life?

EH: I guess I was specifically wondering what it is that you feel your work touches upon that is contemporary.

DS: Well, I can describe it only in words that are not specific, such as “sensibility” and “feeling”, words that kind of don’t mean anything but I don’t have other words to use. The sensibility of our time…not the sensibility of the artist.

EH: For me, when I look at your work, there’s something about the fact that the beauty is always paired with both this delicacy and this real harshness, that I think is wonderful and kind of makes the paintings a bit spicier. To me that’s a more contemporary mode of working. I don’t think that that’s necessarily all there is, but that’s one thing that jumps out at me.

DS: Well, those two opposites are part of the whole. That’s part of why I like tribal arts…which have grown on me more and more over the years. It’s this sort of raw expression of art, which is really the opposite of my own work, which is kind of delicate and controlled. There’s this animal energy and that’s what really attracts me to it. I think maybe that energy comes into the parts of the painting that are kind of chaotic looking, I suppose; expressive.

EH: I think it does. You know, I’ve always personally been interested in polarities and how they play out in paintings. And I think for me, so much of the strength of your painting comes from that juxtaposition of polarities, of this intense harshness and sort of primal thing on the one hand and then this really sophisticated polish on the other hand.

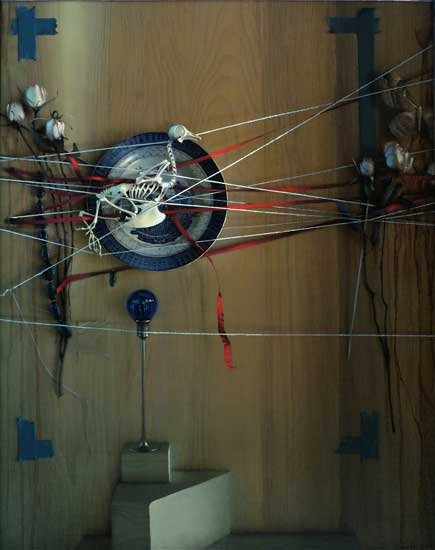

“Pencil Sharpener” Oil & Board 12″ x 9″ 2005

DS: Well, thanks, and the duality is how we interpret the world in which we live…how we express…that’s all we have to express with. You know, hot and cold and light and dark—soft and sharp. That’s what we express through paint. And you would think it’s been done since the Pleistocene Era, that it’s been fully exhausted by now, but in fact it hasn’t…there’s still more that we can do.

EH: So, there’s hope.

DS: You know what, there’s going to be lots more after our generation, too. It just will not run out. You know, in the 19th century, some music critic, a very knowledgeable music critic, had concluded that all of the notes that were available had been used. So, he claimed, there wouldn’t be any more new music. And this was in the 19th century!

EH: That’s really funny.

DS: It is. And he was not a dummy…he was just incorrect in his observation. It’s true, all the notes had been used.

EH: Well, it’s not the notes—it’s the combinations.

DS: Yeah. And then that becomes infinite, so there’s no exhausting it. I wish I’d live long enough to see what the next generation of realist painters is going to do, but you’re just going to live throughout the duration of your own generation, so that’s asking a little too much.

“Landscape & Pansies” Oil & Board 24″ x 30″ – 2003

EH: Could you tell me what your most important formal concerns are when you paint?

DS: Well, good drawing. And good drawing doesn’t necessarily mean precisely accurate. Although I strive for accuracy in drawing, it’s not completely accurate. But at the same time, where it’s not accurate, I think it acquires a certain expressivity that’s the reason it’s worth doing. Expression is the whole purpose. Otherwise, you can do really technically correct artwork that is lifeless. I want to express that level of emotion that is meaningful to other people besides myself. To me first, but to other people, too.

EH: When I visited your website, I saw that there were mostly still-lifes that are displayed, and when I’ve been here in your studio during visits, I’ve been marveling at all these incredible portraits and figures that you have up on the wall, and I was wondering if can talk a little bit about—.

DS: Well, the website has not been updated in about 10 years…9 years, anyway. I’ve always done portraits and figures in the life-drawing classes that I’ve taught and attended through probably 30 years, so I actually have access to a model every week. And sometimes two models a week. So, I’ve always had my hand in it. And I have mountains of drawings in charcoal to show you and small paintings of models and so forth. But the thing that has made a huge difference for me is the versatility that photography has now that it never had before. And that is because of digital imagery being able to correct for the shortcomings of photography. You can make it look so much like the original image in life. So, I think photography is a much more useful tool now than it ever was. Even though it was used extensively in the 19th century, by the artists that I mentioned, for example—Jules Dupre, Breton, Bouveret. It’s more useful now than it ever was. It’s so funny to me how so many artists publicly disdain the use of photos, but privately use them.

EH: I’m glad you touched upon that, because that’s a big thing nowadays.

DS: Oh, it is. And it has been as long as I’ve been painting…long before digital images came along. It was a crutch, or it would not be possible to make good artwork based on photographs. But if you study closely the work of those who bring life, imagination, creativity, energy to it, you can do great work. It’s a really useful tool for artists. What you said earlier today is true, though: it’s a real pitfall when a painting doesn’t go beyond a photograph. I really don’t like paintings that look like photographs and I strive to avoid that in my own work.

EH: So, for young painters who choose to use photographs, what advice would you give to prevent their work from being just a copy or something that’s very stale and lifeless?

DS: Probably, do exactly what you’re doing: paint a lot of still-lifes from life. And paint landscapes and portraits and figures, if you can. Because you need to train yourself to see that way and get acquainted with how the world looks through direct observation. The only real way, I think, to learn it is by practicing it. As I was saying earlier, I painted for about close to forty years and I’ve only been using this computer monitor for maybe the last three or four years. So it’s a real recent thing for me…and I was as much of a firebrand in opposition to photography as anyone for years. So, it completely surprised me when I started looking at images on computer monitors, and adjusting contrasts, filling in dark shadows and toning down bright lights—I’ve been amazed at how useful it is. I’ve completely altered my own position on that.

EH: That’s very interesting to hear. You know, there are many young painters, myself included, who have been discouraged from painting realistically at various points in our education—.

DS: Still?

EH: Oh, yeah, still…absolutely.

DS: Because that’s what was happening to me. I mean, when I was a student, and I had to eventually just block all that out because I knew what I wanted to do. And whether it was going to find its way into the mainstream of contemporary art criticism or not…I’m sorry I interrupted your question.

EH: All I was saying is, because so many people are still being subjected to that stigma, as in, realism is the one thing that you really can’t do in order to be valid in painting, right? That’s why it’s especially gratifying to see someone like you who’s doing it and doing it at such a high level, both technically and emotionally.

DS: Thanks. I’m surprised that’s still going on. But it was something I faced heavily. I found those contradictory inputs very confusing and I lost a lot of sleep myself over what is “valid” and what isn’t, and so forth.

EH: It seems like such a silly question, really.

DS: It is.

EH: Once you’re out of school and just trying to do what you do…. ?

DS: Yeah, it’s a waste of energy. You know what, you just trust your instincts, for God’s sake. If it feels right to you, if it feels honest, then that’s what you should be doing. And you’d need to disregard what is genuine and true for you…how could that be natural at all? I just couldn’t do it, it would be a pretense: it would be utterly disingenuos.

EH: There’s this perception, taught at art schools and various universities, that if somebody is painting realistically or in some way that’s considered polished that it’s because they’re trying to please a certain audience as opposed to pleasing themselves. I found that for all those students (like me and like, I imagine, you) who came in and were just taken by the visual appearances of things and wanted to paint from life, wanted to explore the way things looked and surfaces and all these things, it’s the exact opposite. We would go away from our own natural inclinations to conform to professors’ or critics’ notions of what was or was not a worthwhile pursuit.

DS: Just because it was brought to a high level in the Renaissance, Baroque, and through the 19th Century, it doesn’t mean it’s exhausted.

EH: Do you have any thoughts about what’s happening in painting now and where it might be going?

DS: Well, it’s such a vast field. There are so many categories of painting. Let’s say specifically representational painting of the academic tradition. I see a lot of talented people who weren’t around before…young people who are on fire and that’s exciting to me. I cut you off before about art school and what were you saying?

EH: I was just thinking about how now there’s started to be this resurgence in realism, but it seems to be mostly limited to ateliers and things like that and is not really being given any real cred in many universities—for the most part, there are a few exceptions.

DS: I think that’s changing. They want to meet the demand…they’re probably losing students. I would say that young people want to be challenged. They’d go in and see artwork that doesn’t make any sense to them and requires no skill to execute and they’ll think, “Well, maybe I’ll just go be a lawyer or a doctor.” I have a feeling that’s what’s happening with a lot of bright young people. And the other thing that you were saying about instructors discouraging that direction. Well, there’s this really unconscious undercurrent that sometimes happens (I’m not saying “always”) that sometimes when an instructor has not succeeded in his or her quest in art, he or she doesn’t want the students to either. That could be a component of discouraging.

“Hatchet and Apples” Oil & Board 16″ x 12″ – 2001

EH: Probably subconscious, I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt.

DS: Really subconscious. There’s a movie called “Art School Confidential.”

EH: Oh, yeah, I love it. And I found it to be so incredibly accurate. The opening sequence in particular is hysterical. (I once showed the movie to Stuart Shils and his wife and young son. It had been a couple of years since I had seen it and I had forgotten how crude and explicit parts of it were, and here I was, showing it to a child. I spent the whole time blushing furiously, while my guests were very amused.)

I recently watched your video interview with the Denver Art Museum. I thought it was really well-done and showed a lot of interesting things in terms of your process and the way your paintings develop. Also, what you had to say was really insightful. But it just left me wondering, is there anything about painting or about the artist’s life that you wanted to talk about and haven’t had the chance, that you think might be helpful for people to hear?

DS: Mostly, when I talk about painting, especially in art classes, I talk about technical things. Because to me, without craft you can’t go anywhere. That’s essential, so that’s what I emphasize. That is what people want and need.

EH: It’s like a vocabulary that you could then use to actually say something.

DS: That’s right…that’s well put. I think the rest of it, things such as taste, discretion, statements, those tend to be unspoken. That’s what I hope to inspire in them. What I see happening in the really talented young realist painters of today (some of them are pretty darn impressive) is that there can be a certain deficit in discretion and taste and too much sentimentality. (Points at a painting of a mother and daughter.) That’s probably the most sentimental thing I’ve done. And it felt like I was going out on a limb…I am going out on a limb. But, you know, Madonna and Child, what could be more authentically human than that?

EH: Absolutely.

DS: I thought it’s a real profound part of our existence and I’m going to try it even at the risk of sentimentality.

EH: For myself, I found that for a long time I was scared of being too sentimental or overly emotional in my art and it really limited me. I mean, sure, I also have a negative reaction when something is very over-the-top, when something is too saccharine, but I think that I was so scared of even touching upon that kind of emotional territory that I left too many doors unopened and they’re starting to open now, for the first time. So, I’m glad to hear that you’re attempting things that at first thought might appear to you to be too sentimental and then you realize there is a whole world to explore within that.

DS: There is. One of the things I like to do as an artist is to challenge my own preconceptions.

EH: That’s a big deal.

DS: (Gestures toward painting of woman in a hat smiling.) I’ve never painted someone smiling, so I’ll paint someone smiling.

EH: But, I have to say, that’s the creepiest smile!

DS: Creepiest?

EH: It is!

DS: It wasn’t meant to be. It was meant to be straightforward.

EH: There’s something about it, though.

DS: What?

EH: I don’t know if it’s something I can articulate, but there’s just something about the gesture, the pose, the darkness underneath the rim of the hat, and that smile just peeking out from under there, that gives me the chills a little bit.

DS: The chills—in a good way or bad?

EH: Oh, both! No, no, I don’t think it’s in a bad way, at all.

DS: To me, what’s really going on is, it’s a big toothy smile. Part of the way I thought I could contain it was to have it in shadow. If those teeth were very bright they would really jump out. Listen, I think I have that whole head too dark.

Barry & Jacqui’s Oil & Board 30″ x 24″ – 2001

Trailer Park Oil & Board 12″ x 18″ – 2000

EH: You know what I think it is? I think it’s the fact—looking at it closer now—I think it’s the fact that so much of the difference between a smile and a grimace or the baring of the teeth, deals with what the rest of the face is doing at the same time. You know, the expression in the eyes. And because that’s obscured by the shadow, because of this whole ambiguity about it there, it leaves us feeling a little unsure…which is not at all a bad thing.

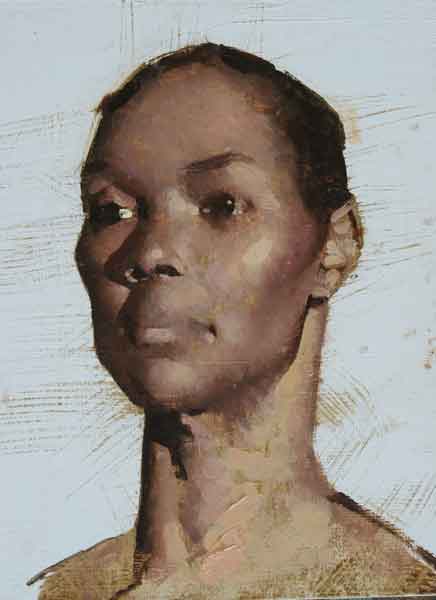

Oh, and another thing I wanted to ask you about, that I spoke to you a little about the last time I was over here, is your choice of background. It is this kind of glowing, slightly yellow, pale field that, to me, kind of places all your figures in this liminal space, sort of an in-between, neither here-nor-there….

DS: Yeah, that’s what it is.

EH: Maybe somewhere in between physical and spiritual, something like that.

DS: You know, it’s a void state. To me, it’s an enveloping light, and it has to do with other people’s experience, an experience I’ve not had and don’t want to have…and that’s the Near-Death Experience. Did you think of that?

EH: I thought of that.

DS: People describe being enveloped by bright light. And again, I have no interest in having a Near-Death Experience, but I’m intrigued by those stories that are remarkably consistent. Practically everyone who has had that experience tells the same story. But the paintings may not come across that way at all to other people, and that’s okay; they don’t need to. And it may be more effective in some paintings than in others. It’s the wrap-around of the light that sort of has to do with that.

EH: Sort of an embrace….

DS: There’s a painting by Andrew Wyeth called ‘Revenant’—it’s kind of a ghost which is enveloped in white light.

Chicken Skeleton” Oil & Board 20″ x 16″ 2004

EH: I think that one of the things that painting does for me that is so moving and important is that many times it tries to embody in the physical something which is non-corporeal. Something that is so incredibly elusive, and here you are, working with these materials—the canvas, the paints, the brush—and trying to somehow translate that and it’s incredibly difficult, but such an undertaking worth doing.

DS: I don’t think I always achieve it. I think sometimes…sometimes…. And even if that isn’t accomplished, it can still be a good painting.

EH: Absolutely.

Well, thank you, this was just wonderful. I really appreciate your time. Your work is beautiful and it’s great to hear your thoughts.

DS: I have to tell you, it’s pretty interesting to me that you thought of that world-between-worlds, with the enveloping light. I don’t know if anyone else has suggested that.

EH: Well, it makes me think of that letter that the poet Rilke (who was the lover of Balthus’ mother, Baladine) wrote to the young Balthus about liminal spaces, regarding Balthus’ birthday, which fell on February 29th.

Rilke in 1921 on the Crac:

Many years ago I knew an English writer in Cairo, a Mr. Blackwood, who in one of his novels advances a rather attractive hypothesis: he claims that at midnight there always appears a tiny slit between the day ending and the day beginning, and that a very agile person who managed to insert himself into that slit would escape from time and find himself in a realm independent of all the changes we must endure; in such a place are gathered all the things we have lost (Mitsou, for instance) … children’s broken dolls, etc. etc. …

That’s the place, my dear B., into which you must insert yourself on the night of February 28, in order to take possession of your birthday, which is hidden there, coming to light only every four years! (Just think how worn out, in an exhibition of birthdays, other people’s would be compared with this one of yours which is so carefully tended and which is removed only at long intervals, quite resplendent, from its hideaway.)

Mr. Blackwood, if I am not mistaken, calls this secret and nocturnal slit the “Crac” …

This discreet birthday which most of the time inhabits an extraterrestrial space certainly entitles you to many things unknown here on earth (it seems to me more important and more exotic than the Brazilian uncle). What I wish for you, my dear B., is that you’ll be capable of acclimatizing some of these things on our planet so that they can grow here, despite the difficulties of our uncertain seasons.

quoted in Nicholas Fox Weber’s Balthus: A Biography, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1999, pp. 84-5

EH: And Balthus so often seemed to paint his figures in a dusky light that really intensified the colors. You know, the way that colors get so much richer right before the sun goes down, in the moment between day and night. And also, he’s trying to catch that elusive moment between girlhood and womanhood, so he’s going after those really transitional points, and that’s what I thought of also when I looked at your work—in a different way, of course.

Well, thank you so much for doing this!

DS: Oh, sure, you’re welcome. And thank you.

Daniel Sprick was born in Little Rock, Arkansas. He studied at the Froman School of Art and The National Academy of Design and received his B.F.A. from University of Northern Colorado in 1978. His love of drawing and the development of his oil painting techniques began at the age of 4, with influences stemming as far back as Robert Campin and Roger van de Weyden. Sprick has had numerous solo exhibitions, participated in many group exhibitions, and has his work in private and public collections throughout the United States and abroad. He is currently represented by the Arcadia Gallery in NYC

Elana Hagler is a staff writer for Painting Perceptions.

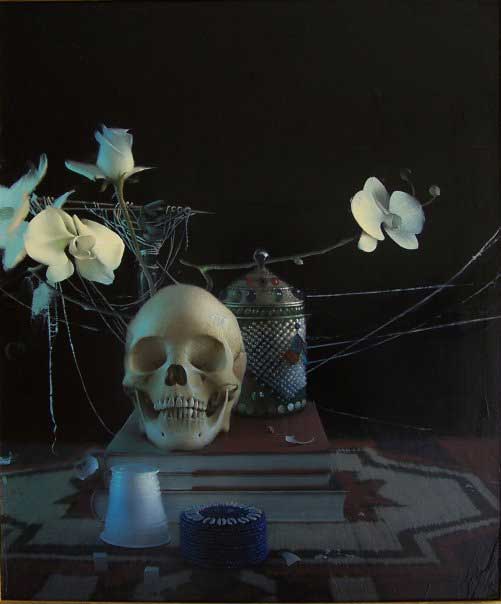

Vanitas Oil & Board 64″ x 84″ – 2006

Daniel Sprick in his Studio – Photo by Elana Hagler

2009 Denver Art Musuem Video interview with Daniel Sprick

Nice work. Appreciate being able to read the interview with him. I really liked the comment about an element being the artistic equivalent of adding a pinch of salt!

Fantastic interview! The paintings are stunning and it’s great to peak behind the curtain and get to see some of the thought process behind it. These interviews are like a public service for art lovers. Thank you!

Thanks, Hank and Thom. I’m in the fortunate position of being able to conduct the interviews that I would want to read myself. It’s sort of like how Alan Feltus once told me to paint the paintings that I want to exist in the world. So, I get to talk to people who’s work already intrigues me and who’s thoughts I’m already curious to hear. And I’m so glad to get to share my interests with all of you and also very gratified when I hear that someone else found it interesting, enjoyable and/or helpful. It was great fun being able to do this with Daniel.

Terrific interview with the amazing Daniel Sprick. Articulate, literate and just fascinating, on both sides, and this thing of photography an interesting problem. I used to admire the earlier work of Chris Berens, its equally haunting oddity and then with his success his works seemed not very different from Disney productions and even given a conscious play on that archive as America, Disney productions themselves were already that. This temptation must be profound for painters such as Sprick with such technical virtuosity, curiosity or visual acuity. (Having spent summer in Italy with Israel Hershberg I’m beginning to think many of the painters I like are myopic, with very thick glasses.) There’s a point in which the ‘punching of holes’ in dark or light becomes in itself a too ready made ‘trick’ and yet it is the origin of painting. Last year’s BP Portrait prize winning painting looked like a Sprick but seemed manifestly reliant on digital imagery in the facial focus in ways Sprick’s portraits and unsentimentally naked people didn’t. Now, these more recent ones of his and his embracing of sentiment feels in some way, for some reason, a fall into temptation and a degraded image – but then perhaps he is right, that this is now the necessary via negativa and there’s no way back to the light, except through it.

Terrific interview,

Best,

Robyn Gardner

wonderful clarity of light and atmosphere to these. Thanks for the introduction!

Thank you for this interview. I regard DS as one of the handful of most important American painters today. Now, if you somehow could do an in-depth interview with, say, Jamie Wyeth…

I don’t post much, but this is just to let you know that your blog has lots of appreciative but silent viewers. Keep up the good work of ferreting out good painters

I adore Daniel Sprick’s work. I went to his 2011 Arcadia Gallery show and saw a painting that really blew me away. It was a tall 3′ by 8′ painting of a nude woman(http://arcadiafinearts.com/gallery/pastexhibitions/2011/03sprick/#/1/1/3/) standing in a semi-darkened, perhaps twilit room, standing on a dark carpet. The model’s pose, gesture, etc, is almost a cliche of “art school model pose”, but I was struck by several things in the painting.

The first was the subtle presence of veins, blood, etc, in the woman’s thighs, hip, and stomach regions. Sprick painted the form to be “realistic” in terms of light, form, etc( the conventions of realistic painting), but also painted subcutaneous ephemera. The experience of the work posessed the physical type of intimacy one might experience if one’s face was inches away from a body.

The light in the painting and the emphasis on the tactile nature of the female nude notwithstanding; the pose, gesture, etc may seem academic. To speak bluntly, the painting may appear to be a simple “girl in a room art school” nude.

However, the most compelling aspect of the painting is a peculiar ambiguity. It is a low light level painting, i.e. a 430Pm on a cloudy February day in Massachusetts (my experience) (or whatever the time was in Colorado at pre-dusk), yet the woman, standing on a dark rug, seems to glow and float in the image.

The light and color on her calves, feet, knees, seem unlike the light situation of the rest of the painting. The effect is an almost Christ-esque floating, and one can pull whatever religious, spiritual, etc conclusions one may from that appearance.

I think the topic is relevant because Elana Hagler asked Daniel Sprick about his white, bright backgrounds in recent portraits, and their religious, spiritual implications.

This painting seems to address that question within a context that may be considered the most mundane, obvious, “girl in a room” art school situation imaginable; yet vastly transcends the stereotype and approaches a physical reality ( veins, blood, etc under stomach, hip, thigh, skin;) and a spiritual reality implied by the “floating” effect of light on the woman’s calves, feet, legs, etc.

I found it to be an incredible painting to observe, and I am a huge fan of Sprick’s entire work, excluding the heavy-handed floating flower paintings.

Sitting in my studio in Normandy on a rainy summer day looking for motivation I came across your interview with Daniel Sprick. Some very interesting things said and I went to the museum video too, which was very well done. I will come back to your site more frequently now.

I have really appreciated this interview. I’ve watched it several times now.

I am an artist – very realistic still-life. But there was a missing part in my training and I’ve been horribly, horribly stuck for many years. Finally it seems that I’ve worked my way through that awful space and I’m back on the road to making great art again.

This interview is so frank and so true. It’s really been inspirational to me.

Thanks so much for your work – Daniel and Elana.

I keep checking back on this interview with this amazing artist. I saw his work seven or so years ago for the first time, and was immensely moved and deeply, deeply impressed, by the technical virtuosity and sheer beauty. Then I found my way to other painters who for a time or in some ongoing way have had some profound impact, and wasn’t sure that I liked the last of these portraits entirely, felt the photographic drift as more ‘there’ in some way which i thought might be sentimentalizing, but then as I paint and struggle on, I keep returning to his work, these strange portraits which do push edges in some peculiar way, which is not just a technique. His pictures stay with me, like an image bank that has now been seared in my mind, memory, very much like works of those greats of the past he mentions – I see ‘Sprick’ moments and compositions in buildings and edges and tools and furniture. I expect he’s had an impact on interior designs. Whenever I check back in, just to look at beautiful and coolly intelligent pictures I’m always, always, overwhelmed again by some passage or painting. I listen to these two interviews, Elana’s and the Denver film and feel always reaffirmed – and not all wonderful painters do this – that there’s a sense in striving oneself, that the discipline and practice of painting has been reaffirmed, made worthy, respected by the way Sprick talks about his work, but also by Elana ostensibly straight but also very subtle questions, and submission of herself as still learning when obviously a highly accomplished painter .

Much appreciated interview.