by Elana Hagler

Alexandra Tyng is a painter who lives and works in Philadelphia. She has a B.A. in Art History from Harvard and an M.S. in Education from the University of Pennsylvania. In terms of her painting education, she is mostly self-taught, having examined the work of the old masters, reading and researching about methods and materials on her own. She is best known for her landscapes, portraits, and narrative figure compositions. Alex Tyng is represented by the Fischbach Gallery in NYC, Dowling Walsh Gallery in Maine, gWatson Gallery in Maine, and Gross McCleaf Gallery in Philadelphia. Her work is included in numerous public, corporate, and private collections across the United States and abroad. She is also the founder of the philanthropic initiative “Portraits for the Arts,” a program that supports Philadelphia’s art community.

Elana Hagler: Alex, thanks so much for joining us here. I’m particularly excited to talk to you because I feel like we have so many interests and concerns in common. Also, one of the things I love about your oeuvre is that you really work across genres. You are well-known for your landscapes, but you also do portraits as well as complex figurative, more narrative compositions. So many people stick to a very specific niche, but you seem to broadly embrace a number of passions. You mentioned how someone once told you that as long as you stick to landscapes, you can be part of the avant-garde art scene, but if you paint portraits, you will be marginalized as a commercial artist. Has your experience been very different or do you find that there is still this stigma attached to working in portraiture?

Alexandra Tyng: Thinking back, I can see what that person meant, because that really was how the art world was in the 70s. At the time I rebelled against the idea of choosing one or the other, and I just kept on painting both. I was just at the beginning of my career and nobody knew my work well enough to pay that much attention to it anyway. In fact, the portrait world was and is so entirely separate from the world of selling art in galleries that I had two completely different careers that almost never crossed. At a certain point the managing of these two parallel careers became too exhausting and time-consuming, and I realized I needed and wanted to find a way to bring them together. By that time, the art world had changed dramatically and portraiture was being accepted as “fine art.”

EH: In your interview with the Newington-Cropsey Foundation, you talk about not having wanted to go to art school because of this perception of being forced there to come up with a gimmick to have some sort of a concept when that wasn’t something that was occurring naturally in your work at that time. And I do know what you mean, because I certainly felt that sort of expectation being applied to me from various critics when I was in school. Do you feel that your studies in art history and psychology have influenced the direction that your painting has taken? Also, do you feel like you had enough external input from other painters whom you knew from your community that there wasn’t really a lack of that kind of more formal painting educational feedback for you?

AT: Actually I was always interested in concepts, and I tried intermittently to put some of my ideas into the first figure paintings I did in high school. But I didn’t know any other contemporary artists (like Bo Bartlett and Vincent Desiderio) who were doing this, and the galleries I knew weren’t showing figures. I’m not sure how ready I was then to work consistently on developing my ideas. I was kind of embarrassed by them, really, I think because not only was I painting realistically, but also I was expressing my feelings directly and sincerely, not trying to be cool or ironic, I didn’t have the confidence to do that in the prevailing climate. As a teenager, I read books about things like the warping of space-time, layers of time, and paranormal events. I was practically brought up on Jungian psychology, and I was fascinated by the analysis of fairy tales and the talk of archetypes and symbolism and synchronicity. I was already interested in different historical periods, and people—their motivations and the relationships between them. So when I got to college it was natural for me to major in art history with a minor in psychology, which added a lot of depth and specificity to my knowledge. Because I didn’t go to art school, I didn’t get to know other painters in Philadelphia till I joined a cooperative gallery. I made some friends who continue to be friends to this day. But I really didn’t have a large network of artist friends until the internet created a way for artists to interact.

EH: I’m fascinated about how you combine different layers of time in your current figurative work. Can you tell us more about that? Also, like you, I’ve been captivated for a long time with Jungian archetypes (also the work of Joseph Campbell) and fairytales/mythology. How do elements of these concepts play into your work?

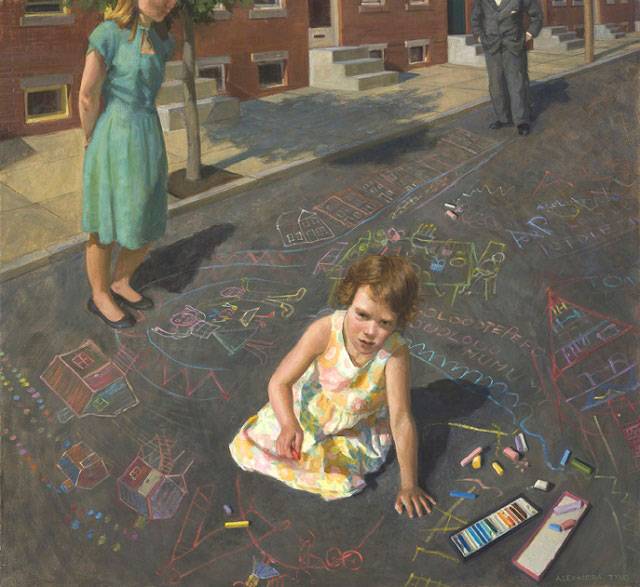

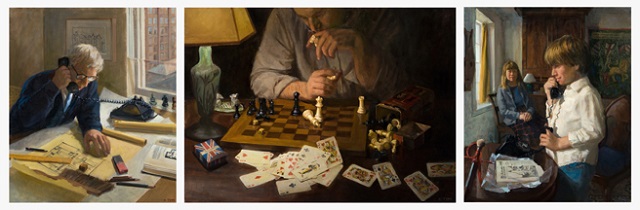

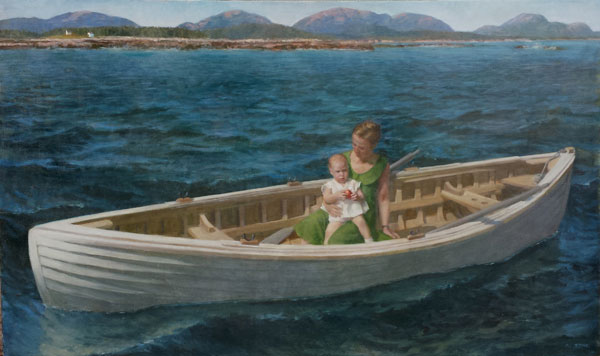

AT: My figurative work is the most personal of all my work. It’s where I allow myself to explore ideas that interest me and really get deeply into them. The scenes come out of my imagination and, because they did not actually happen, the events and people are not bound by time. Sometimes in a single painting I’ll put two figures that are really one person at two different ages, or several figures that lived a hundred years apart. I like it to look as if it were actually happening, or could have happened, so it’s important to me to get the perspective and lighting and viewpoint consistent. It’s all in the service of the concept. The Jungian idea of the archetype makes sense to me, probably because I was exposed to it from an early age. (My mother was one of the founding members of the Jung Center in Philadelphia.) The idea that symbols are remarkably consistent across cultures, even in the past when cultures were more separate, intrigues me because it makes me wonder if all human beings have in us some genetic memory of the Big Bang. My father used to say that “matter is spent light,” If you think about it, all living things came out of the same matter that was created at the beginning of the Universe, so it’s possible that we all share a way of finding connections and patterns, and assigning meaning to forms. I incorporate a lot of symbols into my paintings, but I don’t like to tell the viewer how a painting must be interpreted. It’s no fun to spell everything out for the viewer. I try to create a whole environment in which symbols are part of the setting and interaction between people, so that there are many layers of meaning, many possibilities of meaning, and I’m leaving the painting open to interpretation. I believe there’s always an aspect of visual art that is unseen. You can’t predict that, or control it, but you can try to put your non-visual thoughts and emotions into the painting when you’re working on it, and hope that some of that is communicated to the viewer.

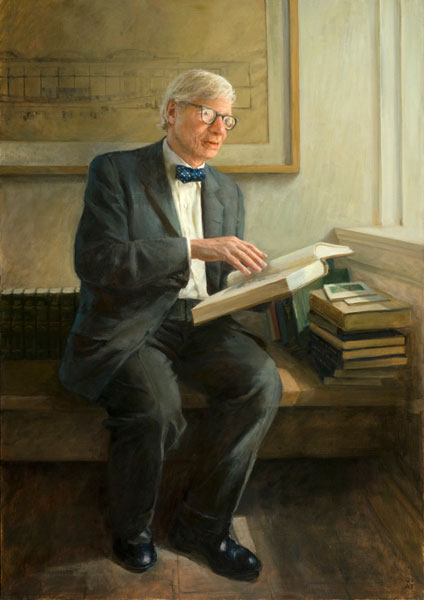

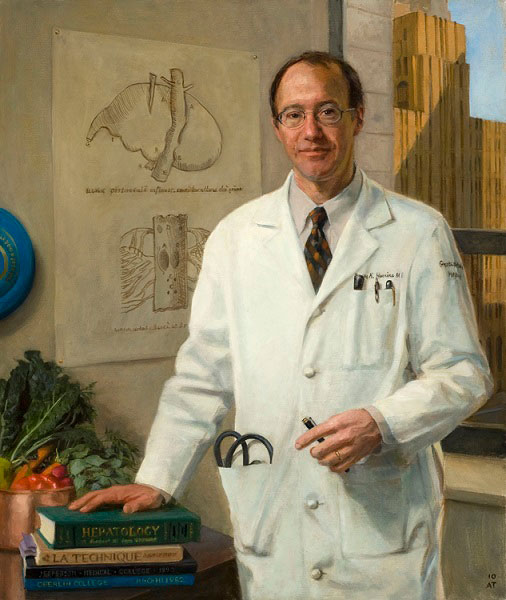

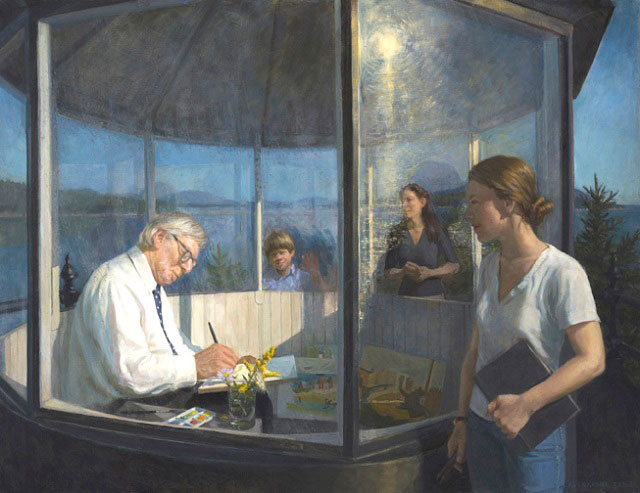

Louis I. Kahn, oil on linen, 52″ x 36″ Honorable Mention, Members Showcase, Portrait Society of America, 2011; Collection National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

EH: One thing that we have in common is that it took both of us a while to accept that painting could actually be a “real” profession that was a valid pursuit for a lifetime’s work. Could you tell us a little about how you can to terms with this very defining choice?

AT: For me it was a matter of figuring out how to bring the practicalities of earning a living together with the conviction inside me that told me I was put on Earth to be an artist and I couldn’t really do anything else quite as significant with my life. My parents [the architects Anne Tyng and Louis Kahn] were not much good at making money, so they really couldn’t advise me on the practical aspects of being an artist, but they also couldn’t support me financially. I always knew I would be an artist, but after college, reality hit. I had no clue how to make money to live on. Every time I was broke, my friends would say, “why don’t you get a real job?” I’m sure all artists have heard that at some point from well-meaning people. I had different ideas of how I could earn money on the side doing this or that, until finally I realized my art was of much more value than anything else I could do. Now I see that there are thousands of ways artists can make a living, you just have to figure out what suits you the best.

EH: I’ve seen many portraits fall into this trap of these sort of worn and recycled presentations and clichéd approaches. How do you keep your compositions and just the entire sense of the portrait fresh?

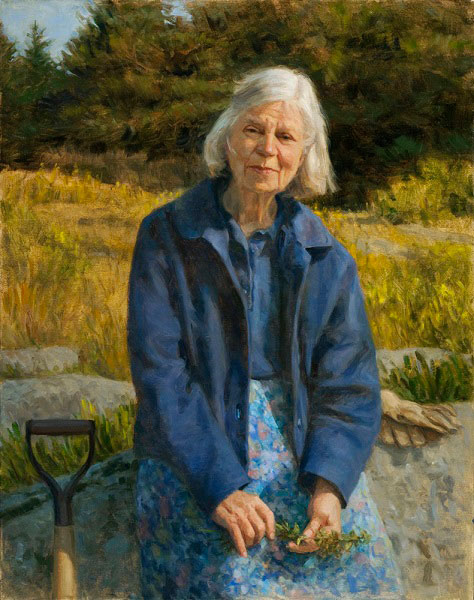

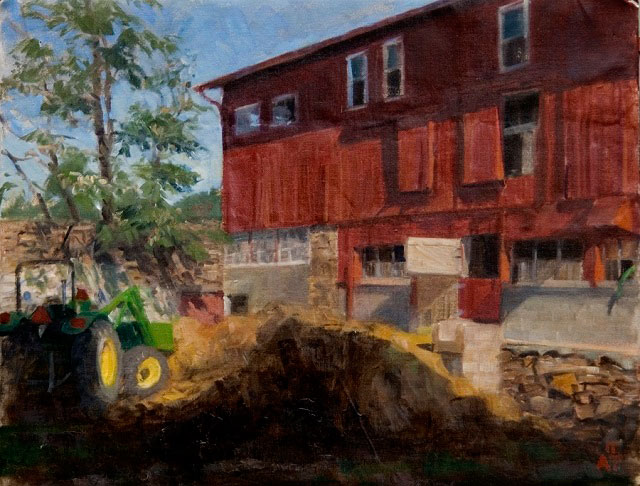

AT: It helps that I don’t just do portraits. I usually have a variety of things going on. In the summer I spend a lot of time in Maine, painting landscapes outdoors, and I’ve been a field instructor at the Plein Air Convention in Monterey for a couple of years. My outdoor paintings become studies for larger studio paintings. I am usually planning or working on a figurative piece in the studio. So portraits are just one of many things I paint, and I always approach a portrait as a new adventure, a new problem to solve. As part of the process, I enjoy painting people from life and getting to know them. Also, I think it has something to do with the way I approach a commission. My parents were architects who did all their work on commission. I grew up paying attention to how they approached the process. They didn’t just take an order from the client; they listened to what the client wanted and then used that “program” as the starting point for inspiration. So, for them, a commission was a collaboration with the client from which something greater emerged. And that way of working with portrait clients seems natural to me.

EH: Many people seem to fear that working on commission can be very limiting in that it may involve a good deal of artistic compromise. You mention that you find that working on commission can be an enriching and invigorating thing rather than a limiting thing. What advice do you have for young painters who may be new to the process of collaboration with a client?

AT: Remember that the artist-client relationship is a process of collaboration. If it turns into an adversarial relationship, it just won’t work. When you are working on commission, get into the mindset that what you can accomplish together will be greater than what either of you can accomplish alone. Really listen to your clients as they tell you about their vision of the portrait, and use that information to learn about them and to inspire you. The clients’ ideas are parameters rather than constraints; they will help you shape your own vision. And keep the communication lines open. The more you let your clients in on the process, the more they will like the final product.

EH: You mentioned that you only started painting images of your family members fairly recently, because you were to some extent afraid of having people think that you were exploiting famous family connections. I have also been somewhat timid of touching more obviously on issues such as the Holocaust, the general Eastern European Jewish experience, and my particular family stories, which are all so tied up in that past and the whole transitory, immigrant experience. My reticence is because I know that some people talk about the Holocaust in particular as being something that gets exploited (I think those people often have a political axe to grind) and the last thing I want is to feel like I am, in any way, exploiting the pain my family experienced. Still, my family’s experiences have been such a large part of my own emotional inheritance. For me, it all still bubbles around inside, and I don’t really know what form it may or may not take in the future. But for you, your family and the stories they’ve told have now started to make their way into your work, and I would love to hear more about what that means for you and how you found the self-assurance to flick off those nagging doubts.

AT: You bring up a really good point, which is that we all have our own stories to tell. The stories come from the interweaving of our experience with our history and heritage, and also from our personal ways of looking at our experience and processing it. Years ago I read a book about how to see your life as a story and how to tell that story. There are many books on this topic for writers, but the premise can be applied equally well to painting. The author basically said that everyone has stories to tell; it’s just a matter of seeing your own life in a certain way. Something happens to you, and you think it’s thwarting your direction, but actually it’s pointing you in another direction, which you can only see when you are far enough from it that you can look back at the whole thing. It makes a story when you can understand its true shape and meaning. Your description of ideas “bubbling around” inside is exactly what I experienced for years. Like you, the ideas existed in a nebulous state, and I had to wait until they took shape. It really is a torturous experience to live in this state of uncertainty and inner turmoil while ideas are gestating. You wish they were ready to be born but they aren’t yet. I can see how it could make some artists crazy. The last thing I wanted to do was exploit my connection to well-known family members by painting them, so I refrained from that for years. I also wasn’t ready to tell my story because on some level I didn’t realize it actually belonged to me. Once I took on that “ownership,” my imagination was free of constraints, and I was able to “speak up” on things that are important to me—themes in my life, things I’ve observed and felt strongly about. This coincided with a point at which I had enough skill and experience to paint my ideas. But at the end of the process there’s a new uncertainty: Will the painting work? Will it strike a chord with lots of people, not just you? You have to really ask yourself “What am I saying?” and still, when the painting is done, there are no guarantees. Not all paintings are masterpieces. You just have to keep trying, keep painting, and keep exploring ways to communicate more successfully in your own visual language.

EH: Could you say something about your actual technique of painting? Do you tend to paint more directly, or is it a more indirect, layered approach? Do you do preparatory sketches? Do you make an elaborate underdrawing, or do you just jump in with large painterly shapes?

AT: My painting process is primarily direct, though in the studio I apply more layers, I incorporate some glazing and scumbling, and I can make the choice of whether to paint wet-into-wet or wet over dry. The basis for all my paintings is working from nature. Whether I’m painting a portrait head in a studio setup or working outdoors, I’m trying to put down exactly what I observe. In preparation for large studio work, I take reference photos, so I work from both the oil studies and photos. I use the photos to design the composition and decide on the exact proportions and size of the canvas. If it’s a complex figurative composition I do a lot of graphite and charcoal sketches first. Then I print out photos for the background and figures, and I plan exactly where everything is going to go by moving figures around. I prefer to cut and paste rather than work it all out in Photoshop because then it looks too finished and I feel as though I’m just copying a photo. The painting is more in my head than in any of the reference material. When I’m working in the studio, I paint from the computer monitor, the oil sketches, and as many as 20 or 30 photo references strewn around the easel.

EH: What directions are you excited about exploring with your work for the future?

AT: One thing I’m starting to do is to get back into drawing more. I’ve always enjoyed expressive line drawing, but I’m now trying all kinds of new graphite and charcoal and papers, practicing creating fully developed drawings in which I turn the form and control the values and edges and variety of marks. I want to continue working in different genres—landscape, portrait, figure—I like having the option of moving around so I never get bored. I’d like to continue developing my figurative work, continue reading about and figuring out new ways of using archetypes, symbolism, psychology, physics, and ideas about layers of time and perception. I’m planning to continue with my family theme, and I will probably expand my subject matter to include other casts of characters. My overarching goal is to not repeat myself and to continue challenging myself.

View Alexandra Tyng’s recent podcast interview with the Newington-Cropsey Foundation here.

I think this artist,s work is really wonderful. I love the composition of her paintings and they are always interesting.

Thank you, Elana for this interview. Alexandra Tyng is a wonderful artist. I love her paintings. They have that particular quality of “fresh air” you can find only in the works of plain air artist, who is genuinely interested in the subject rather than in self-expression. I guess, one of the secrets that you learn working on commission is that you create painting not for yourself, but for the people to enjoy. Your questions are right to the point and it is exactly what in the mind of every sincere artist. Thank you!

I’ve admired Alexandra’s work since I first “met” her on an early online forum for portrait artists. Beautiful, interesting work. She shines through as engaged, personable, compassionate and thoughtful. Thanks for a great interview.

Wonderful read and so many parallels with my life and persona, though I´m not an artist. Thank you.