I am very fortunate and grateful for the recent invitation by Stanley Lewis to visit his studio and home in Western Mass. and talk in person. Our conversation continued and helped to follow up on the second part of our interview which was recorded previously in our phone conversation. (Link to part one of this interview)

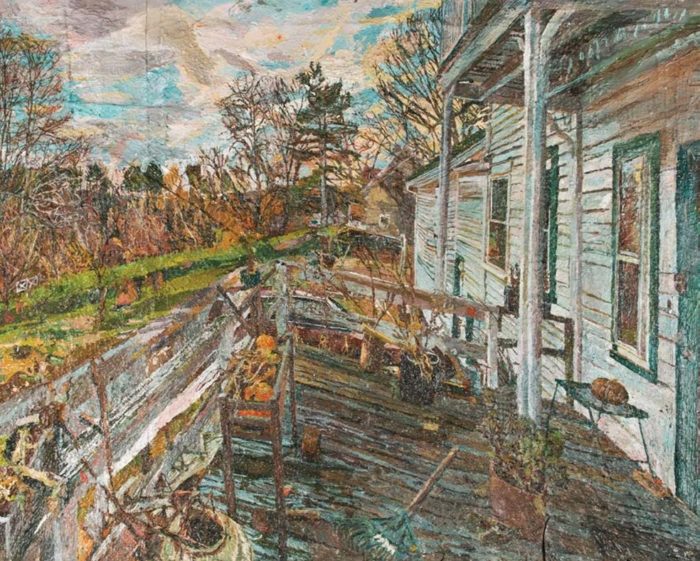

When I arrived he showed me a large oil painting on canvas, a work in progress made over this past winter, on hold now till the trees lose their leaves again. The subject was a view looking toward the front of his home with the light through the trees and the surrounding yard and garden. He uncovered protective plastic sheeting that was draped over his hand built easel stand. As this was a work in progress I decided to respect his privacy and not take photos of his setup or record the conversation–however, the photos above show earlier painting spots. He then explained how elements in this motif informed his decisions for his painting process. There was a large, maybe 1.5 – 2 foot, wooden viewfinder attached to the easel with clamps in which he looked through to judge how elements in the scene related in space as well as to the picture plane. This easel had numerous practical advantages such as ways its construction offered protection from the sun and wind as well as space for the palette and other items.

The painting would expand both in depth and dimension as layers of paint are added or additional sections of canvas attached as needed to meet any needs for an expanded view as determined by the relation of the boundaries of the viewfinder and the canvas edges.

Some sections of the painting that needing protection were masked by clear plastic sheeting and areas needing revision could be layered with clear plastic sheeting used to paint on and then attached using bonding adhesive (such as palette scraping and medium of some sort) additionally new repainted sections could be stapled as well as glued on. It was all very open and nothing was seemed to be held too preciously–instead the goal seemed more to get unity and integrity in the composition. I was surprised by his unconventional methods but after seeing the astonishing surface facture and compositions of his finished paintings, this approach made sense. We briefly discussed how being overly concerned with any technique’s archival longevity seemed less important than bringing integrity and vitality to the painting. That was something the art conservators could worry about in the distant future (if future humans still cared about the condition of paintings when faced with the more disastrous consequences of climate change and such.)

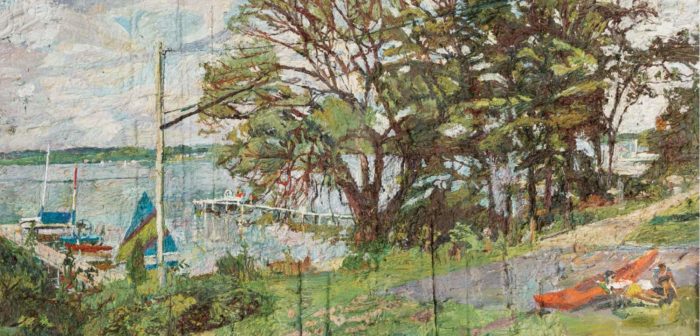

The morass of details and visual chaos one is confronted with in outdoor painting sensibly leads most painters to simplify things as much as possible. Lewis respects painters who go that route but his investigations and perhaps contrarian sensibility leads him to paint nature as he finds it. I couldn’t detect any doctrinaire painting philosophy or nature worship zealotry here, instead–that for him–what works is to trust that careful observation can lead to a greater authenticity and possibly reveal powerful visual surprises–along with directions for the paintings abstract structure. Lewis’ way of merging the observational with the abstraction comes out of the importance of getting a ‘Double Meaning’ in painting that comes in part from his study with Leland Bell as well as his interest in Jean Hélion and Lewis speaks more about this in the interview.

Stanley often speaks in a humble, plain-spoken manner–often stopping mid-point–seemingly to weigh-in on other points of view or add a related thought. He was uncomfortable hearing anything he viewed as over the top praise from admirers. He often focused on the many difficulties he encounters with his daily struggle in making paintings that meet his expectations.

He told me that not long ago he needed more space in his studio and decided to throw out a huge number of his early studies, quicker works and more abstract paintings to make more room for his current work. He expressed dissatisfaction with many of early works and that getting rid of them was freeing and a relief, that he could work with less of the past hovering over him, cluttering up his present concern with spending more time on the paintings, working everything out however long it takes to resolve and that a quicker, gestural manner is no longer the best approach for him.

Lewis also spoke often about the notion of a ‘Double Meaning’ or ‘Double Rhythm’ in painting is more visual than verbal and he expressed dissatisfaction with how he has tried to explain what this meant in his painting. I showed him the quote from the book that Deborah Rosenthal edited Poussin, Seurat and Double Rhythm by Jean Hélion. Stanley loved this quote- but wasn’t sure it accurately explained what he was doing. He wasn’t sure it needed a verbal explanation – preferring to work it out with paint, not words.

The book has a wonderful quote from the Hélion’s Double Rhythm essay that seems particularly relevant and powerful:

The least figurative painter cannot go far without getting a permanent lesson from nature. The meaning of what we create is only expressed in that endless dictionary. This is the only constant, the only light clearing the significance of any picture. The chief point is to work within the meaning of nature instead of its appearance.

And nature is full of facts that are so clear, substantial, already so far transformed into ideas:

The tree, coming from a germ-point, goes toward light, multiplies its directions into space, each of them into thousands of hands, and to catch, to hold, to receive space on an always larger surface, finally transforms them into flat leaves facing the sun.

Birds, going from one point to another and coming back, embracing space, measuring it, rhythmically dividing it and discovering a speed in its modulations.

Fishes, the more spatial beings, actually living in space. They stop at every point of it, have no limits to their progression. They know three dimensions, refined angles, complex continuities. They move in all directions, without shocks. Birds just make long hops. Only fishes fly. They do not have to come down. They constitute spatial groups. Their body, in contact with the tangible liquid space in all points, receives its call, measures it, responds to it. When one fish moves, in a basin, all others are affected. One goes up, three go down, another describes circles, slowly.

The top meaning of equilibrium is probably “thinking.” Equilibrium identifies in permanently renewed ways, ethical, plastic, everything the painter is capable of. The shape becomes thought. One cannot be parted from the other. The eye-mind of the painter goes over it all, in all directions, extricating, superposing rhythms, blowing through them, to find their longest way, their endless, their simplest, where all meet. When all elements, thus produced by many reasons, the black and the white reasons, many processes, oppositions, rhythms, waves, constitute a complex mass, controlled, solid, unified, totalized, the painter faces it and sees his complex-self in it, as in a multi-dimensioned mirror.

The whole mass of the painting shines like freshly cut copper, shines of its constitutional brilliance, that means blood running, life. Identity is reached between substance and thought. To work one is to work the other. The plastic error denounces the ethical error. Painting is a language.

–Jean Hélion, from Axis: A quarterly review of Contemporary “Abstract Painting & Sculpture, Summer 1936

Please Note: this is an affiliate link to this book – Painting Perceptions gets a small kickback from Amazon if you buy this book from this link.

Stanley Lewis quoted in Standing in the Artist’s Footprints, Martica Sawin’s essay for the 2016 catalog for the New York Studio School Exhibition(link to full catalog) “The Way Things Are”

“I think of the viewer as myself. I want the viewer to be where I was and to understand what I am doing, which is complicated. I turn my head from side to side to find my picture. I want to get from here to there, not just see a unified central image. I can’t expect the viewer to work that hard so I struggle to unify the sides.”

Martica Sawin explains earlier her Standing in the Artist’s Footprints essay:

Lewis starts a drawing by focusing on one component of a given motif with a fair amount of detail before shifting to another segment of his subject. “I love painting the small things, although I think I get lost in that detail.” It’s not difficult to imagine getting lost in the complex network of thin lines that trace the overlapping tree branches in View from Bathroom Window, West Side of House ( see below ) and other drawings of snow-covered landscapes. The strokes follow every twist and turn of even the most slender branches, weaving a delicate tracery that stays in sharp focus even as the trees recede into the distance, the result of days of labor in the frigid weather. Lewis is not one to edit out anything that falls within his line of vision, like signage or parked cars or backyard debris, so he includes the assertive lines of a pair of telephone wires cutting diagonally across the filigree of branches. A devoted plein air practitioner, he will work outdoors at his easel even as the temperature drops below freezing. When winter finally drives him inside he usually manages to angle his rendering of cluttered interiors to include a sideways view of a landscape through a window.

I invited the painters Dan Gustin as well as John Goodrich to say a few words about their friendship with Stanley Lewis.

Dan Gustin writes:

Last year my wife Cynthia and I spent a couple of days at the home of Stan and Karen Lewis. I have wanted to visit his studio for many years. Although I have been around him in Italy, I was eager to see where he works all year long. I wasn’t sure of what to expect and anxiously anticipated this visit to a great painter’s work and private lair. Nothing could have prepared me for what I was about to see.

Walking into Stan’s studio was a unique experience. It was amazing and overwhelming to see the amount, quality and range of work Stan was engaged in. It was like seeing a new country for the first time with new eyes and few assumptions. It was as if some kind of creative bomb had gone off in his studio, leaving hundreds of bits and pieces of all shapes and sizes all over the studio in every possible direction covering the floors and walls with Stan’s amazing and unceasing output of work. Every inch of space was covered with scribblings, great drawings, discarded scraps of paper, paint and pencil, finished and unfinished paintings, plaster sculptures, wood carvings, paint brushes, hand mixed paint, as well as 12 finished paintings he was sending to a show in NYC.

This was a studio where there was no presentation or formal explanation on what he was working on for the edification of others. It felt like you were inside his head where a kind of living theater of pure and intense creativity ran amuck with no script or plotting of destination. The studio housed his direct action tied to his moment of making. There were were also many copies and transcriptions of painters he loves, mostly in pen and pencil where he continually draws from sources of great painters,and sculptors to best understand how to make his own work today.

I was completely blown away by what I was seeing and how it was so different from any studio I have been in over the last forty years. It brought to mind the photos I have seen of Giocometti and Picasso’s studios, in that, the rooms were filled from floor to ceiling of ongoing work, all relating to some amazing way that made perfect sense to the artist. To me, Stan’s work in the studio is not about a self-conscious presentation set up for the opinions of others, but rather a glimpse into a timeless moment of a great creative mind always in process, always striving and always in doubt.

After leaving Stan’s studio, I was inspired but also bummed out. As I started to make the unavoidable comparisons to my own work and studio set up–I felt I had to take a look and reassess what I was doing and my own process of working in the studio. I had had this incredible experience of being truly in the belly of the beast of this great painter, and it had a profoundly sobering but enlightening effect on me. I left Stan and Karen’s house a much humbler painter and hopefully a bit wiser.

In my opinion, Stanley Lewis is clearly the most compelling, visually honest and pictorially inventive painter today who is working perceptually from the landscape. His incredible passion and relentless will for seeing truthfully, his force of pictorial articulation and plastic construction, are completely unique in today’s art world.

Bonnard spoke of trying to fathom and express “the grand and ancient patterns of nature” in painting. Like many great artists who pursued this search, Stanley Lewis is the heir apparent to that deepest of artistic pursuits–as expressed by Bonnard and the great painters of the past; always avoiding the pitfalls of fashion and spectacle. Instead, Stanley stays true to his vision of painting; trying with his incredible determination and talent to, as he says, “just see the small little things.” Dan Gustin 6/2019

John Goodrich writes:

“The official ritual of evaluating a painting might proceed this way: Stand at a slight distance to ascertain subject matter and stylistic treatment. Move in to register the means of facture; consider their implications about temperament. Move back once more to assess the ultimate realization of concept.

Fortunately, many of us have had the chance to listen instead to Stanley Lewis, who has arguably spent a lifetime proving that true inquiry follows no recipe. In regard to both his painting and his teaching, there seems to have been no divide for Stanley between immediate, everyday experience and artistic inquiry. What interested him in life – be it the latest astronomical discovery, traditions of jazz trombone, or an incident from an obscure artist’s life – became inspiration in the studio and classroom.

Painters may recognize a particular effect: the way, deep within the rhythms of a painting, a detail or passage arrests the eye, pressing itself upon one’s attention for no obvious reason. For years, I’ve thought of such a moment as a kind of “face staring back at you.” Not coincidentally, this is exactly the phrase Stanley used, years ago, to describe a passage that unexpectedly holds the eye, punctuating or summing up the larger movements around it.

I think of the phrase as pure Stanley: a direct and strictly honest experience, practically related, poetically spot-on, and completely unconcerned with tropes of art appreciation. It’s one instance of the free-form inquiry that has always marked not only his thinking about art, but also — and this is what really counts — the spirit behind his remarkable drawings and paintings.” John Goodrich 5/2019

Larry Groff: You have painted abstractly in the past and now mainly paint from observation. Can you say something about what you try to get at with your painting?

Stanley Lewis: I prefer working in manner that is more of a “working class” vision of how things look. I believe in being struck by the beauty of what you see in nature, like how you might sit next to me outside and remark on how great the light was on some green leaves looked or how the wires against the sky could make a wonderful subject for a painting. We’re seeing the same things, the way it looks beautiful today. There is something about going after the simplicity and authenticity of appearances that is what Derain was about. I believe in appearances rather than a systematic method of making a painting work in terms of something like an abstract rhythm. That’s how Leland Bell might put it.

At the same time I also struggle to get all the pieces to fit. If you push it too far it can backfire on you and start to become abstraction. Sometimes I think it’s more clear when you paint abstract because of how it shows more readily what you’re going for and not get confused with the appearance of the things observed in the motif. Trying to get things to sit and work together in the way you want – it often doesn’t work.

LG: Did you see the 1991 movie, Dream of Light, about Antonio Lopez Garcia painting quince tree in his garden? He marks lines on the actual fruit to note where their position to one another on a grid-like fashion. I believe it helps him keep track of changes from the fruit growing.

Stanley Lewis: I heard about it but haven’t yet seen it. I went to see his big show in the Boston MFA a few years ago. I was very impressed, so many great paintings, like his huge painting of Madrid done from a rooftop balcony. His concerns with spatial relationships – how things on the horizontal and verticals relate is similar to what I’m doing. I was also very impressed with his sculpture.

LG: Haven’t you also made sculpture as well? I saw photos online of your sculpture from the 70s or 80s.

Stanley Lewis: I still work on sculpture but in the 70’s I was making a lot more sculpture. There isn’t as much interest in my sculpture as my paintings and drawings. Few people see my sculpture, so I don’t worry about it.

LG: You gave a talk about relief sculpture, about Donatello’s relief sculpture awhile back. I’m curious if your thoughts on sculpture might relate to any spacial concerns in your paintings? How your push and pull the foreground and the background, flattening of some areas and deep recession in others. Also, there is almost a sculpted feel to your paintings with thick impasto or how you might cut and stitch together areas of the painting. Some of your incredible drawings start to look like shallow bas-relief sculptures with the build up of thick heavyweight handmade papers and other surface manipulations.

LG: I’m very curious to know more about sculpture in relation to your work, is this something you can talk about?

Stanley Lewis: It’s really too complicated and I’m afraid it would take too long to answer the questions of how and why. I do think about these issues many times and it’s clear to me how elements in the motif can interrelate but it’s all very abstract and on a non-verbal level. The figure drawings and the sculptures I made connected with trying to figure stuff out related to this.

What is more important for me to say here is that for me it all comes back to Leland Bell. Leland Bell gave lectures on the great French, Italian and German painters. He had us look at Corot and all the most important landscape painters like Claude Lorraine and Poussin. He was constantly talking about them and getting us to look and think about their work in relation to our own paintings. He spent less time looking at our own work. Leland didn’t come in our studio to point out problems, where you needed to fix something. Instead he would suggest looking at how a particular painter might approach the problem.

His example influenced how I taught continuously for my whole life till about 15 years ago. I would put slides up for at least an hour or two every class day and we drew from the images of these paintings. I would draw all the time; it could be a Durer woodblock print or a Bruegal. I immersed myself with copying paintings. Courbet, for instance, was a huge inspiration to draw from. This almost always involved working with the figure. I would find all kinds of incredible secrets going on with copying master figure paintings, mysterious underlying structures in the composition, not readily visible, kind of hidden there mysteriously in the pictures. These drawing studies were confusing but I was very engaged and hours would go by and I would realize after coming home that I didn’t really understand what I just done.

But in time, after making so many copies it would start to affect my own paintings and drawings and then I started to do sculptures of these drawings, to try to work out the problems and get a deeper understanding of the issues.

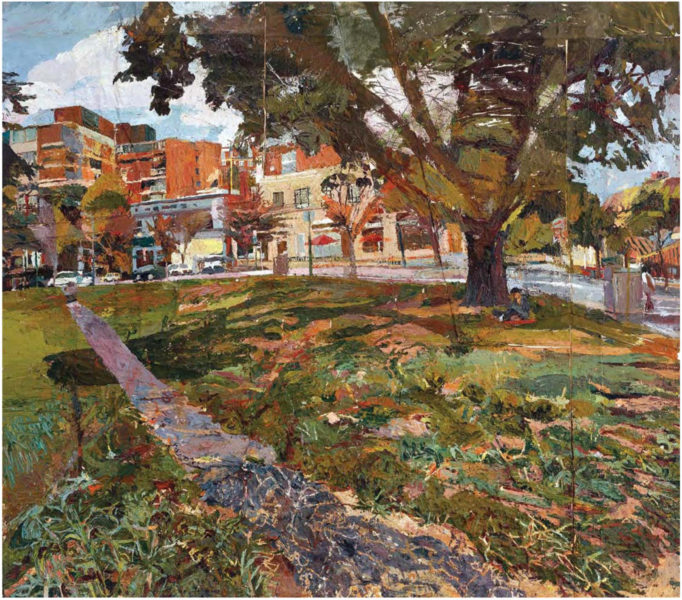

Corner of Connecticut Ave. and Calvert St. , 2002, acrylic on paper, 40″ x 45½”, Collection of William Louis-Dreyfus

LG: Clearly Leland Bell’s teachings have been a huge influence on you. But you don’t easily see it from looking at your paintings, which look nothing like his. What else can you say about how Leland Bell affected your painting?

Stanley Lewis: It’s too big a subject to properly answer but I can make a few simple attempts.

Stanley Lewis: Leland became my teacher by accident but I immediately fell in love with the guy, I just loved him from the start. When I first heard him talk I knew he was the guy for me. Everything he said made sense to me. That’s not to say there weren’t problems at times. I once said something that Leland didn’t like and for a long time I wasn’t even talking with him. But now, none of that is important. I just knew he had the right ideas even if I didn’t always understand it. I knew his heart was in the right place. He often talked about Hélion who became important for me as well as Derain, Balthus, Giacometti who he also talked about.

ed. note: for more check out this Link to the Stanley Lewis LSU lecture in March 14, 2018, on the Balthus, Giacometti, Derain 2017 exhibition at the The Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris

In addition to talking about drawing and space he talked a lot about about color balance and color relationships across the painting; which was important for me to hear. He never really liked the big heavy paintings that I made but he did like my little studies. The painters he talked about were often difficult to understand, Derain especially. You would become imbued by his enthusiasm these painters. Actually, over the years I’ve figured out a simple way to think about them. It’s that the French on a higher intellectual level and more complex, the Germans–like Hoffman or Kandinsky–are more physical – who push and move things around. I think I’m more inclined to be a German type who pushes and pulls things here and there, I’m not sure that is a good thing. It is really too complicated. Leland’s love of all these artists: Derain, Dufy, Renoir–he wasn’t as involved with Cézanne but of course he loved Cézanne. The ancient artists, like the Sumerians and the Egyptians, were opened up for us by Leland. He took us to see these things and we’d try to figure out what the hell’s going on. Looking at these works opened up all these possibilities, things with these double meanings, the double meaning the Egyptians and the Sumerians created, we’d see this and try to put it all together.

LG: The early Renaissance painting evolved out of the Gothic style where the flat 2D space emphasizes its linear structure. Giotto and others combined that with the illusion of an observed naturalistic 3D space. Is this something Leland was concerned with in his paintings and talks?

Stanley Lewis: I want to make this clear about what Leland said, he didn’t see it all through an art historian’s viewpoint, he kept breaking down historical patterning. All these painters were faced with these problems about the space and how to present it on a two dimensional surface and so on. Those are the painter’s issues, he’d say it in an unhistorical way. And he’d say whatever they decided on they’re all based on a sort of painter’s core problems. That’s how I remember Leland putting it. He was very interested in Derian who in turn was very interested in Roman painting, the Pompei still lives and portraits long before the Renaissance. So the whole concept of the Renaissance which became masterful innovations in masterful, technical–huge elaboration, he jumped you right back and the Coptic textiles, he kept breaking down historical patterning, he’d say you’re all going to be faced with these concerns. I’m saying this maybe for the first time for myself. He’s saying you’re all going to be doing this stuff. It’s what painting is in its nature. You take a pencil and piece of paper and then look at something or you think about something and you try to put it down, all these same issues will soon come to your mind, like how do I do it? How do I make a face? How do I find it inside the painting? If you’re kind of the kind of person who has a knack for this, then you get these issues right away, the issues are simple and clear.

LG: I think that any history that presents art as a linear progression of quality is wrong– a history that implies art goes from the primitive to the advanced–doesn’t sound right to me. That the high renaissance was better and more advanced than the early renaissance. This thinking maybe leads to the notion we can only go forward that you can’t return to past ways of working. I remember reading something where you said something like cubism is not over just that the fashion changed and people went on to other things. Isn’t all of past art fair game for reinterpretation? Couldn’t cubism be as relevant today as it was 100 years ago?

Stanley Lewis: I think that’s exactly right and I’ve always thought cubism is a part of the figuring out the problems of making a painting function. All painters are cubists in a way. Abstract expressionists are definitely cubists – cubists with a swirling brush or something. I’m not sure how to explain this without it all becoming hopelessly complex.

LG: Ok one last question and I’ll let you go. In this day and age where so many people are distracted by their phone and computer screens and even have difficulty paying attention to their immediate surroundings much less pay attention to art. What is it about painting that is still important?

Stanley Lewis: I am not optimistic about what the future will bring to the art schools. So many art schools have changed to a more post-modern orientation and using digital screen to make art with. Some people seem to be able to make something out of it but painting has definitely got its own rewards. And I can’t imagine a situation where you have a room of thirty young kids that at least one or two are going to see that painting is the best fit for their personality. Painting is something you can mess around, get dirty–like what Leland used to say, it’s colored mud. You touch it, get on your clothes, you smell it–It’s real. Who wants to sit in front of a screen all day. So I think there could still be hope because if there are rebellious people, who are not going to go along with the program, they’re going to paint. It’s just a natural thing to do. It’s sloppy. You have to get screwed up to do it. It’s all connected with some kind of primal thing that’s going on in your mind. That’s the key idea. Louis Finkelstein said something about this along these lines. I think it was in the book of his writings. I think it’s about knowing your mind. If we want to have healthy minds dealing with what we see that’s where painting can try to help deal with these issues because the ambiguity of vision–the unclarity of vision is what painting is trying to sort out. So, really there is a health issue here.

Painting is certainly waning in the educational system. But at least there is hope in that the museums haven’t been torn down. I mean you still people looking at these paintings and asking what is going on in these paintings? What is this all about? It’s the most challenging and stimulating mental and intellectual activity, painting can be extremely thought provoking. You know what is going on. What does it mean? So I’m hoping there’s always people who are going to be interested in this. That’s my answer.

LG: That’s a great answer and gives us hope. So many people are disillusioned now. They’re getting burned out with pace of everything, information overload and are visually over-stimulated and they want to slow down. Maybe more people will turn to things like landscape paintings to slow down as an exercise in mental health if nothing else. Like you said.

Stanley Lewis: One reason why I’m not such a good talker is that I tend to stress the wrong things. Once you’re out there painting and you begin to rethink your whole painting and you have to repaint your whole painting. So that is a problem. But then you start doing it. Well, then the sun comes out. I mean you’re out there. You know it couldn’t be a better place to be doing whatever you’re doing. And there are great moments, always great moments. I can’t think of a more exciting thing to do. It’s just that it’s so up and down. I mean the chance of success with your painting is very limited. I think that as long as you take the attitude of accepting that you’re not likely to succeed very often. If you cut back on the number if issues you deal with, like what happens when you paint smaller – you get a better chance at succeeding. That’s what I would tell anybody. When I do a small painting– it can work. It’s these big ones that are so impossible but then do anyway.

LG: It’s like the quote from Queen Elizabeth that you sometimes see on sympathy cards – “grief is the price of love”. The greater the love and commitment for painting the greater the pain and difficulties when it doesn’t work out, perhaps a fair price to pay in order to live life as a painter.

Stanley Lewis: That’s a beautiful idea. That’s what my wife needs to tell me. She’s always trying to get me to see things with a more balanced perspective. That’s a good balance between joy and pain, that pain is just a part of the whole process. I know that is true, I want people to paint; it’s fun! It’s especially fun at the beginning when you start out painting. Once you stick it out over a long time, you push yourself and then you get to increasingly harder problems like the ones that I’m dealing with.

An insightful video lecture on a painting by Stanley Lewis by Michael Bogin, Professor of Studio Art at Hobart and William Smith College who describes the 1985 painting, O.C Backyard, by Stanley Lewis in detail.

(note: this telephone interview has been edited and revised extensively for clarity and brevity)

Wonderful inspiring interview. Thanks Larry.

This was fascinating, and heartening… a good example of why I look forward to all the interviews appearing on this blog.

I just love him. Everything. Thank you!