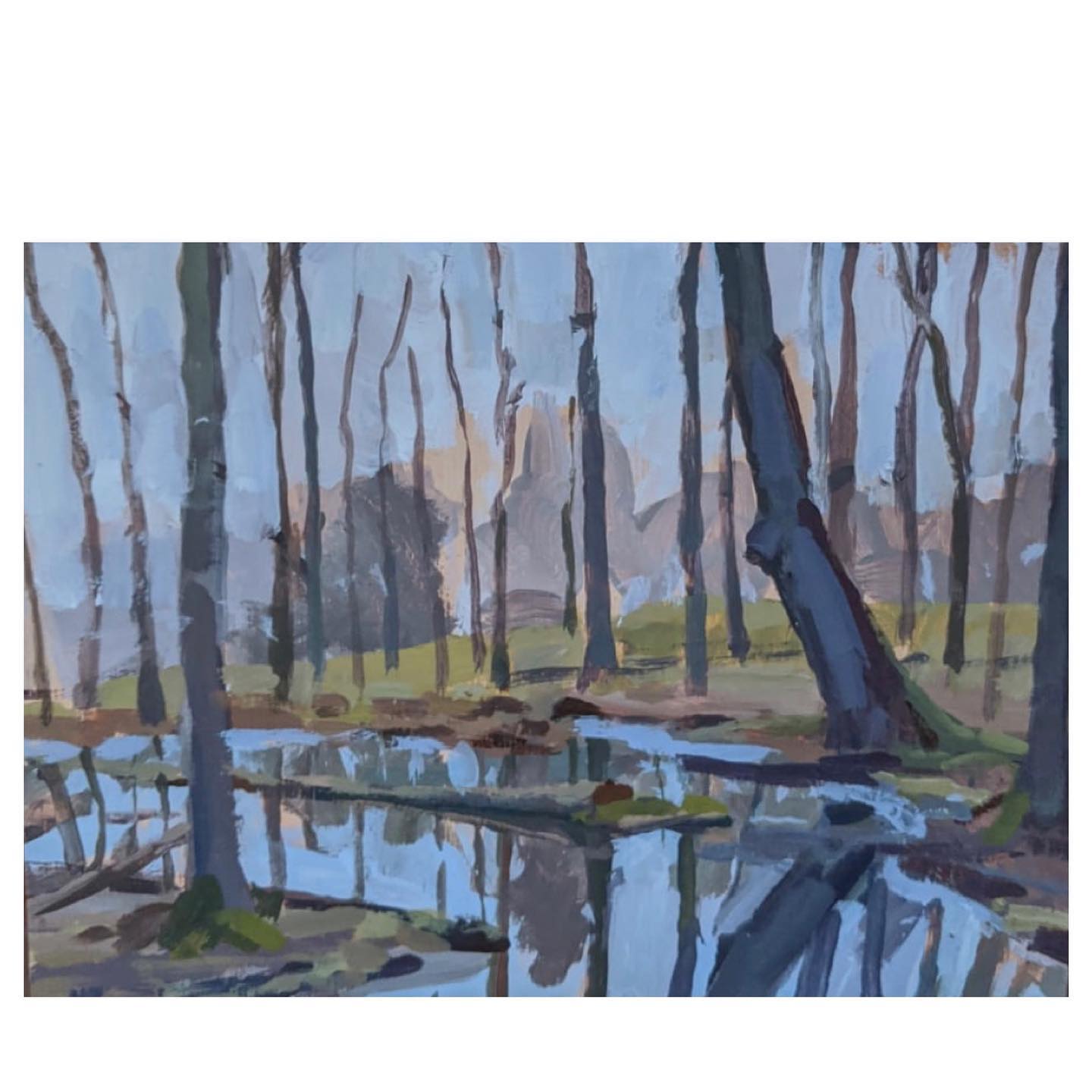

I’ve long admired Todd Gordon‘s paintings and several years ago I was fortunate to both meet him and view his solo show at the George Billis Gallery, then in Chelsea, NY. Like Rackstraw Downes, Gordon’s intensely observed, large-scale paintings of both industrial and country landscapes are painted on-site over many sittings. Recently, I was surprised to see his painting of small, alla prima landscapes of forest scenes near his home in Sweden that he posted online. In this recent work, I was captivated by the visual poetics of his economic paint-handling and the surprises of his compositional explorations. I decided to ask him if he’d agree to show these works here on Painting Perceptions along with answering a few questions about this new work. We made plans to do a longer, more comprehensive interview at some future point but for this article, the focus is on these new smaller alla prima works done from life.

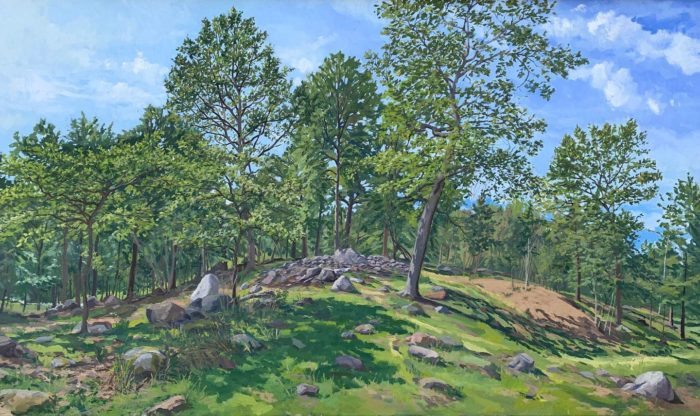

Gordon lives in Stockholm, Sweden, a city comprised of 14 islands and surrounded by forests and parks and where he is able to walk to many of these sites, such as the national city park in the middle of the city which is twice the size of NYC’s Central Park. He also spends time painting in the Swedish Archipelago about an hour outside the city and consists of over 30,000 islands.

When asked what brought him to Sweden from New York City, he said that he and his wife, Michela moved there in 2013 after his wife, an architect and designer accepted a job there. They now have two small boys, two and four years old.

In talking about how these new works came about he told me:The impetus for these new premier coup paintings came out of the culmination of several factors that occurred simultaneously in February last year — I had just taken down my last solo show at the George Billis Gallery in NY, we were deep into the darkest and coldest months of winter here in Sweden, I was getting more teaching jobs, and the pandemic was really starting to ramp up globally. Due to the frigid temperature, lack of daylight in the winter, and increased childcare responsibilities because of Covid, I consciously decided all these paintings would be done in 1-3 hours, as opposed to months or years, they would be much smaller than my panoramic landscapes, I would use acrylic on paper or directly on panel, and I would shift away from the urban environment and paint the natural landscape.

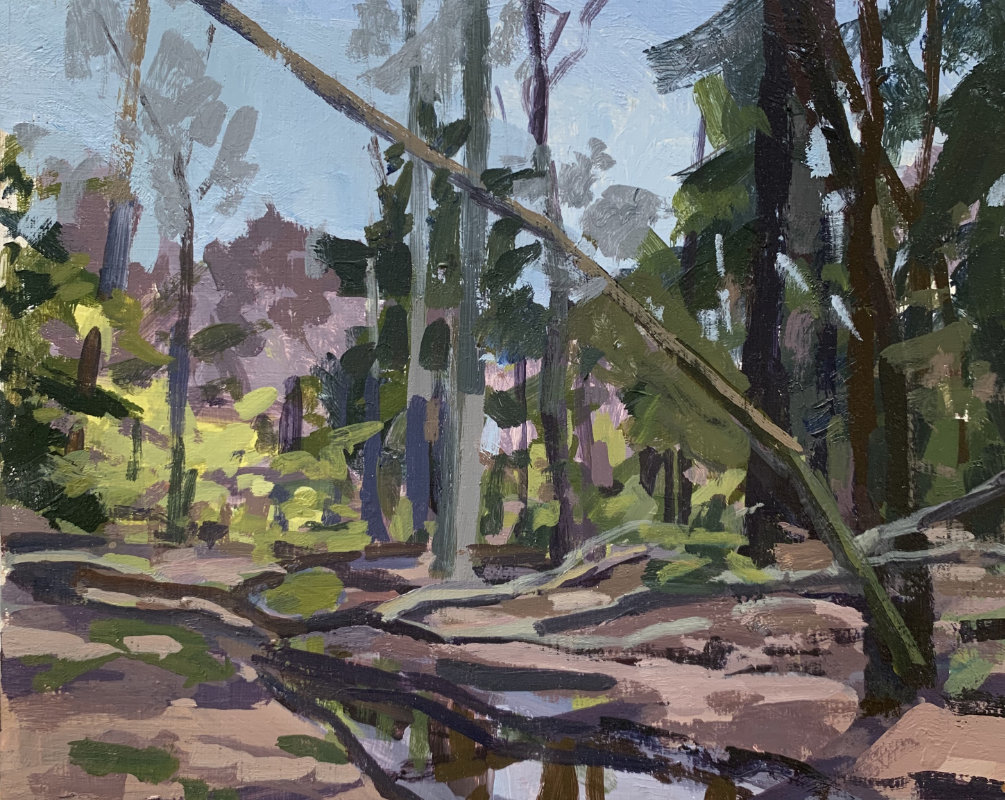

When I began these small paintings on paper, I was sure that I would eventually return to making larger oil paintings in this same landscape. I wasn’t even sure what to call them. Were they studies? Drawings? Paintings? Did it matter? During the spring and summer, I switched back to oil and I think I made 7 or 8 larger paintings, working much more slowly over several weeks. None of the larger oil paintings were made from the premier coup paintings nor were any of the locations or sites the same as the previous works.

In October, I had a biking accident and I broke my left wrist (my painting hand) so I went back to working with acrylic on paper. While my wrist was healing, I was going out and painting with my right hand, both hands, whatever would work. Since then, I am still working premier coup, primarily with acrylic. In painting this typically more conventional, pastoral landscape, I still wanted to maintain a certain level of anonymity or universality with the subject matter, in that the observed landscape must still operate as a vehicle for making a painting above all else. I am more interested in using and building upon the physical aspects of the landscape to inform the formal decisions in the painting process. I want to use the landscape to try to make better paintings — to push my work somewhere else — not to record a specific place or capture a moment for sentimentality or posterity. So instead of trying to paint everything I see, I have been editing and focusing on the essential elements of what I’m looking at.

When I began these small paintings, I think I initially imagined it would be a way for me to keep working during the winter, while I was teaching, in the middle of a global pandemic. I was pretty sure that eventually, I would return to making some kind of larger oil paintings in this same landscape.

As of now, I see these works as what they are — acrylic works on paper or panel. Maybe they are drawings? Maybe they are finished paintings? Maybe they will be studies for larger paintings which I will scale up and paint again on location? I’m looking forward to warmer weather and longer working hours to discover where I go from here. I’m searching.

After reading Justin Wolff’s 2015 interview with Todd Gordon I wanted to know if Gordon’s thoughts about his outdoor painting and its relation to plein air painting had changed any since starting this new work and more about what he had said in the 2015 interview. His response was illuminating and probes the heart of what many landscape painters and others who work from observation find important. I will first present how Gordon responded and then provide context with select quotes from the previous interview with An Interview with Todd Gordon. by Wolff, Justin, PhD., LOFT, Vol. Q2, 2015, p.p. 28-38.

I would say that yes, of course, working quickly and outside is very much the way typical plein air painters work. I guess I don’t see myself as plein air painter because I am more interested in using the landscape, or the phenomenology of being in the observed landscape, to make a painting than I am in “capturing a moment” or depicting a scene or motif. I’m not interested in painting the Swedish forest because I feel compelled to document it or because I feel some sort of sentimental or romantic attachment to it. Indeed it’s quite the opposite— I have no attachment to these places. I have no history with them. For making paintings, I find this quite liberating. This is not to say that I am eschewing specificity or accuracy of the observed world. Hardly. In fact, I am trying to articulate the same level of specificity and verisimilitude that I might have achieved in painting that I would have worked on for months or years, in a matter of a few short hours.

I really don’t see these paintings as vastly different from my other work. These new works are still grounded in observation and perception, as is all my painting. Perhaps I am allowing for my own natural sensibilities or instincts as a painter to play a larger role in the process — more emphasis on drawing, trying to balance intuitive, perceptual responses with empirical observation, seeing larger shapes, structures, and relationships and how they operate holistically within the rectangle.

Although I work outside, entirely on location, I don’t associate my work with typical “plein air” painting today. For example, my work is not done premier coup: a typical painting takes weeks or months to complete. I’m not interested in “capturing a moment” but rather in conveying a much slower, more gradual building of time and space, and, ultimately, experience. The longer I stand in a space, the more I see and the more the space inevitably changes. Whether it’s the waning light during the day, the shift in seasons, or something mundane like a parked car that drives away, the landscape is always moving. It’s alive, no matter where or what I’m painting. Getting this down on canvas is the perpetual, and maybe entirely futile, challenge.

I’m interested in the poetry of the every day and what’s overlooked. I don’t set out to embellish – to make a place look more beautiful than it actually is – but to convey, as honestly and specifically as possible, the visual facts before me.

The below is excerpted from the 2015 interview with Todd Gordon by Justin Wolff

JW: To mention “the poetry of the everyday,” especially in the context of plein air painting, invokes a familiar narrative from art history. Baudelaire famously associated spontaneity with modernity: to paint “en plein air” was to paint quickly – to paint as a “modern” painter – whereas to paint slowly was to paint as an “academic” painter. But you’re implying that painting slowly has current significance, right? How do you think about your work in the context of critical terms such as “academic,” “realist,” and “modern”?

TG: I was recently listening to a podcast interview with Israel Hershberg, a painter I admire a great deal. He was talking about painters going outside to work not as some kind of primal need to “return to nature” but rather as a way to unburden themselves from iconography and narrative. He believes going outside to paint was the real sea change, in that it allowed painters to get back to pictorial language and the plasticity of painting – the flatness of the picture plane, abstraction, shallow space, reductive forms.

I agree with Hershberg. Does that make me a “modern” painter? I suppose one could argue that it does, though I’m more interested in being a “contemporary” painter, someone who makes work of this time. When I see much of the work coming out of today’s atelier programs, work that I would call “academic” painting, it does not seem to be of this time. In these programs it’s all methodology, dogma. There is this understanding of modeling and rendering based on intense study and life drawing, but it’s a very technical and ultimately narrow way not only of working but of seeing the world. A close friend of mine used to teach painting at one of these so-called atelier programs in New York and he constantly complained about the palette he was required to teach his students – all browns, umbers, earth tones, black and white. We used to call it the “dead palette.” That’s one connotation “academic” painting has for me.

I never learned to paint this way. They didn’t teach techniques like that at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), and, in fact, I can think only of one or two instructors who even knew how to teach this kind of painting. So, no, I don’t consider myself to be an “academic” painter. I’m sure, however, that there are people who would look at my work and call it “academic,” but I suspect that has more to do with the fact that it is representational and not abstract. In terms of painting slowly or quickly, I’m not sure the old categories of “academic” and “modern” painting hold true in today’s anything-goes climate.

My method of working slowly came about after years of feeling like I was making familiar plein air paintings when I worked premier coup. I consciously decided to slow down and spend more time on location, looking. The painter Stanley Lewis talks about reacting to something that one of his teachers, Leland Bell, stressed, which was that it’s impossible to paint everything so you have to edit and paint only the essentials. Lewis decided that he was going to do the opposite of what Bell advised and instead try to paint everything he saw. I arrived at a similar place with my own work after a few years of painting outside. I was capable of making competent, quick, one-shot paintings, but I didn’t feel like I was pushing them as far as they could go. I decided to really slow things down and get things right in my work. In doing so, I was trying to take myself out of my paintings – trying to forego gesture, or exaggerated hues – and paint more empirically.

In a sense, painting everything allowed me to restrain my personal expression, which felt more real. The experience is about physically being in a space and looking. Frankly, I’m not interested in interjecting my feelings in my paintings. I am already there in so many ways – in the decisions made leading up to the actual painting process itself – and I don’t want to be “in” a painting any more than I already am. It’s a way for me to avoid sentimentality.

I think that slowing down the process of painting is a reaction to the incredible speed with which technology has changed our world, specifically our visual world. Going to a museum or gallery to spend an hour looking at a static image seems like an antiquated, even quaint, activity today. Yet this is essential to painting, and to understanding painting: one needs to slow down – spend time with, look at, and think about painting. This is all part of the experience. And it’s a physical experience. Paintings have presence – surface, scale, even smell – and you need to be with them, in the same room with them, to really experience them. They need to be experienced in time. In answer to your earlier question, perhaps painting slowly today is a subversion of Baudelaire’s idea about academic painting. Maybe slowing things down is a reaction to the frenetic pace of our digital world. Perhaps working this way is a search for something more tangible or authentic in the experience of looking.

Does that make my paintings modern? Contemporary? I hope so.

JW: Can you elaborate on what you mean by “sentimentality”?

TG: I associate sentimentality with saccharine paintings of conventionally beautiful places. Such paintings are genre scenes – antiseptic visual tropes instantly filed away in our collective visual memory alongside other similarly recognizable images. The idea of capturing a memory plays into that, I think – saving something, a snapshot, for posterity. I want my paintings to be much more than that. Again, they should be experienced slowly, over time, in the same way that they are made. I want the viewer to feel the same kinds of visceral, tactile, physical, and sensorial things that I felt when I was standing on a trash-strewn corner in Bushwick. I’m painting what I see, not something I am embellishing or making up out of my head.

JW: To push the point a little more – when you’re painting, or when you’re reflecting on your paintings, is art history something that you think about? Are there traditions or artists that you’re particularly influenced by?

TG: I think I’m more like artists such as Stanley Lewis, Rackstraw Downes, Andy Lenaghan, and Antonio Lopez Garcia – contemporary landscape painters who work primarily outside, from life. I identify with Lewis in that I also try to paint as much information as I can (“try to paint everything,” he says) and with Downes’s emotional restraint and discipline. Downes has written about feeling a seemingly unlikely bond with Minimalist artists, such as Donald Judd, and I, too, feel that connection to the conceptual tenet of “what you see is what you get.” I’m not interested in forcing a metaphor or interjecting a political agenda into my work. I think the world is already interesting enough as it is. All I need to do is look – and look again.

So, yes, I am very aware of the art historical canon and the trajectory, or trajectories, of painting. I’m conscious that I’m a contemporary painter living in the twenty-first century who makes observationally-based landscape paintings, and I see myself as part of a lineage of artists going back centuries who shared similar ideas and excitement about the possibilities of painting from life – the London School, Fairfield Porter, Giacometti, Morandi, Cézanne, Van Gogh, the Impressionists, Corot, Turner, Chardin, Vermeer. When asked whether he saw himself as a peer to Turner, Rembrandt, and other masters, Frank Auerbach, quoting Hemingway, said he was “in the ring with them.” I think that the longer I do this the more strongly I feel that affinity and the more I look back to others not only for answers but for support. I hear voices that say, “This is possible.”

Gordon holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting and drawing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a Bachelor of Arts degree in art history from Northwestern University. He has taught as an adjunct lecturer in studio art and been a guest lecturer and critic at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Brooklyn College, SUNY Purchase College, Montclair University, the New York Studio School, and Hudson County Community College. He is represented by the George Billis Gallery in Westport, Ct. Learn more about Gordon at toddjgordon.com.

For all of us putting mud on textiles in the woods, here’s a reminder that we are not alone. Wonderful piece.

Thank you Richard your comment is much appreciated. My hope is that my efforts with this site help to strengthen and inspire our community of painters. It can sometimes be difficult to see the forest through the trees – that we don’t stand alone.

Impressive ! Thanks for the post.