Review by Christopher J. Graham, guest contributor

David Kordansky Gallery’s exhibition (link to the online exhibition) of the late Sam Gilliam shows the artist’s relationship to material exploration and displays a specific period in his prolific output. This show features a shift away from the acrylic-dyed draped canvases that made the Washington DC painter famous. It focuses instead on Miles Davis-influenced, stretched works that include large amounts of paint build-up and directional zips on the picture plane.

A small canvas, Untitled (1975), featured a surface divided into equal quarters. On the untreated ground, a peach-y-hued color permeates the surface, establishing a color field. This peach-y-hued color is seen in many of what I believe are considered the white paintings.

Untitled creates a setting in which the viewer can become acquainted with a microcosm of the painterly terms found in the show, which include stained canvas, all-over space, zips, collage, and rhythm. Untitled, like all the paintings in the show, features beveled canvas stretcher bars.

The bevels provide a sculptural element, perhaps a bit self-consciously, but in addition to this, they also push the painting into the viewer’s space, into the gallery. This is worth noting in comparison to Gilliam’s drape paintings which floated a notion of envelopment; the beveled stretchers mark a clear distinction between the painting and the wall.

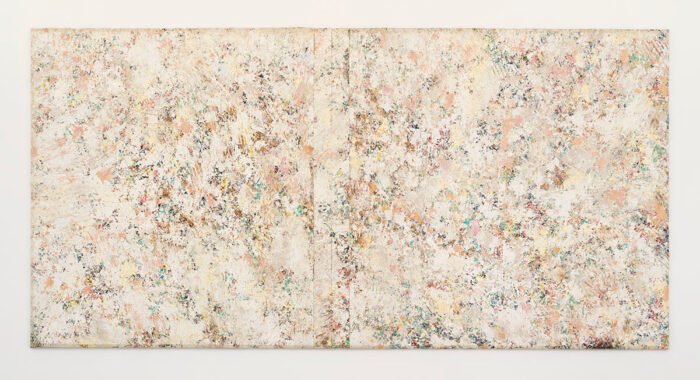

Double River, 1976, acrylic on canvas with collage, 90 1/2 x 181 x 3 inches, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

This distinction is echoed in Double River (1976), a 19-foot-wide painting with a wide vertical band near-center on the canvas. The peach color previously described in Untitled covers the surface, intertwining with large dabs of white paint that creates an impasto ground. A curious moment in the painting is the dark waxy material course throughout the canvas. The darkened umber passages are welcome threads against the blues, pinks, and yellows that appear to be much of the work’s focus.

The asymmetry of Double River’s heavy zip creates a division just left-of-center on the picture plane, promoting an enfolding in this space. The enfolding established by this zip forces the viewer to contend with their specific position while viewing the piece.

Double River’s horizontal expanse is echoed in For Brass (1976) which features three zips running the center length of the canvas. These zips create a perception of quick left-to-right/right-to-left movement across the canvas. The third quadrant from the bottom of the work contains a field in which the colors turn from warm oranges and reds to green. In the piece, Gilliam lays cool grays across the foreground, which both obstruct and accentuate popping oranges and reds found in the painting. These warmer colors signal a depth in the canvas, pulling the viewer toward the ground.

Much of the writing surrounding this period of Gilliam’s output mentions the influence that Miles Davis and John Coltrane had on his work. This becomes apparent when taking in the work with the hard bop rhythm of Milestones-era Davis in mind. This rhythmic focus is found in the staggered zips of Weighed Anchor (1976), where the viewer can skip across a vertical surface. The effect of this composition comes across as a stuttering, a staccato note change, which contrasts with a vamping ground.

Abacus Sliding, 1977, acrylic on canvas, 90 1/4 x 120 1/2 x 1 3/4 inches, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

Abacus Sliding (1977), has a nondescript rectangular shape made of canvas collage that begins to take the form of a spiral. The center rectangular spiral draws the viewer nearer. The ultimate effect of Abacus is misleading; once the viewer is close enough, they are confronted with the multicolored canvas ground. This ground instigates a scale shift within the composition. The foreground’s black paint becomes a ground on which the view the speckled chromatic shifts of bright yellows, baby blues, and lime greens.

With its warmth and deep radiance, Abacus Sliding feels the most related to the artist’s earlier work. Where it diverges is its use of the collaged canvas to establish a focal point for the viewer. Articulating this guidepost for the viewer’s benefit is intriguing when considering the lower left corner of the piece, where a rusty red meets an ochre contrasting heavily with a light blue. Cluttering the lower left of the work with passages of strong color allows the lower right to become a reprieve from density. The multicolored ground acts as a slight framing device. When viewed with these observations in mind, it is revealed that Abacus Sliding relies on these structural elements to organize its composition.

Earth Element (1977) acts as a bridge between the lighter works in the show and the moody Abacus Sliding. With its own focal point, the piece prominently features a wide, mostly black rectangle in the lower center of the composition. While this shape causes a grounding effect, there is a frenetic quality in Earth Element not found in the other works in the show. Impasto grays and purples are massaged into place and left to crack when dry. These dry chunks of paint are frequently interrupted by finger-sized smears giving the painting a tumbling motion. Even the grounding rectangle in the center of the work, which shifts to reveal a Prussian blue undertone, is broken two-thirds across, suggesting a triangle. Earth Element suggests that the only true grounding terrain is perpetual motion and constant change.

David Kordanksy Gallery’s exhibition of Sam Gilliam’s Black and White paintings showcases a unique moment in the artist’s career. Fueled by abstract painterly terms and hard bop jazz, the 1975-1977 works featured in this exhibition show Gilliam using a reduced color palette in a way he would not do again. It is an excellent tribute to an artist whose contributions to painting continue to ripple out in contemporary discourse.

Leave a Reply