“CONVERSATIONS: 23 Interviews with Still Life Artists” (link to the books information on the Zeuxis website) unveils a vibrant tapestry of perspectives surrounding the still life genre. This 316-page volume, produced by Zeuxis—an association founded in 1994 by Phyllis Floyd and fellow still life artists—celebrates and seeks to reinvigorate this venerable art form. Named after the ancient Greek painter famed for his lifelike depictions, Zeuxis bridges the past and present by showcasing artists who blend time-honored techniques with contemporary themes and styles, breathing new life into the tradition of still life painting.

Zeuxis has held exhibitions in over 50 nationwide venues —including commercial galleries, museums, and college exhibition spaces—and has been reviewed in The New York Times, The New York Observer, and The New York Sun, among others. Zeuxis’s traveling exhibitions, such as the widely acclaimed ‘The Common Object’ from 2010-12, have sparked considerable interest in still life art, a topic I previously explored in an article at Painting Perceptions “THE COMMON OBJECT”.”

This book presents a rich tapestry of the still life genre through 23 insightful interviews conducted from 2020 to 2023, lavishly illustrated with both large and small color reproductions from the portfolios of 60 artists. Many interviews reveal a shared stylistic or thematic affinity, providing a focused exploration of specific issues relevant to each artist’s practice. This ranges from fluid, expressive techniques to meticulously detailed realism. The visual poetics and aesthetic integrity form a solid foundation that unites all the contributors. Among the more recognized artists are Tim Kennedy, Catherine Kehoe, Elenor Ray, Ken Kewley, Emil Robinson, Daniel Dallman, and Stanley Bielen.

Many of the interviews were conducted during the pandemic, utilizing Zoom, Google Docs, and email to bridge the distance. These conversations spanned a broad spectrum of topics—from the intricacies of studio practices to the roles of observation and memory in the creative process. They also delved into how external forces like the pandemic, family responsibilities, and societal pressures have influenced their art. Particularly fascinating were the insights into what draws each artist to their chosen subjects and the pivotal decisions that guide them toward creating visually impactful work. Reading these discussions from the perspective of the painters themselves—rather than through the lens of critics or reviewers—offers a refreshing and intimate glimpse into the foundational elements of their craft, articulated in the language of paint.

Imogen Sara Smith wrote in her essay, A Writer Looks at Still Life, for this book.

“Still life has always been quietly radical, and today it offers a much-needed antidote to the haste and waste of our ‘attention economy,’ a model of sustained engagement with the overlooked stuff of life.”

The slow looking involved during the painting process and when the finished painting hangs on the wall is neurological nutrition that satiates both the painter and viewer alike.

Building on Imogen Sara Smith’s theme of ‘slow looking’, the interview Unfolding conducted by Joe Morzuch with artists Andrew Marcus and Christina Renfer Vogel further underscores the value of patience and observation in the artistic process. As Marcus and Vogel discuss their methodical approach to developing their paintings, each brushstroke and session builds cumulatively on the last, allowing the artwork to evolve organically. This gradual layering not only unveils new dimensions of meaning but also facilitates moments of unexpected clarity and profound shifts in perception. Such extended, contemplative engagement exemplifies how deep, sustained attention can transform our understanding of a subject, echoing Smith’s insight into the radical potential of still life to enrich both the creator and the observer in our fast-paced world.

Andrew Marcus is characterized by his dedication to prolonged artistic processes, often dedicating several months to a single drawing. This slow pace is a method and a medium through which he deeply engages with his subjects, allowing the composition to evolve and unfold gradually, leading to highly detailed works. He uniquely does not rely on a physical setup but uses the drawing itself as a dynamic setup, enhancing the fluidity of his work. He describes this process in the interview,

“My still lifes are not based on any set up. There is no arrangement of objects on a tabletop. The drawing paper itself is my tabletop. I use a collage technique throughout the whole process, using individual studies of objects, each cut out separately. This enables me to move them about on the paper, sometimes in dozens of different configurations and finally taping them where they will eventually be drawn on the paper.”

Christina Renfer Vogel, in contrast, employs a more flexible approach to time, engaging in both rapid sketches and extended painting projects. Her work serves as a form of “marking time,” capturing the essence of personal life events and relationships through her art.

Vogel states

“I find working from life to be full of potential. It offers me so much discovery and surprise, and it forces me to get into a zone of focus, deep looking and slowness, that feels somewhat radical these days.”

This state of mind resembles the meditative state sought by medieval monastic scribes, who viewed their work as a reproduction and a form of devotion and contemplation.

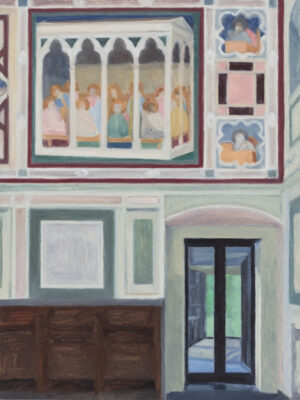

In Unexpected Connections, the late Lynette Lombard (1953-2023) interviews Ying Li and Deborah Kirklin. These three artists share a faster, gestural, and expressionistic handling, directly painted from observation. They respond to light and space by their unique, personal orchestration of the surface, marks, and color feeling. Ying Li and Deborah Kirklin agree that color usage is deeply personal and reflects individual memories and experiences, often aiming to capture an “inner light.”

Lombard recalls what Nick Carone once said about this inner light, ‘The inner light can vary–it speaks to something within you, a certain kind of light you are attracted to. Color can be where the internal memories meet the external perceptions, and you arrive at a sense of light.’

I also loved what Ying Li says here

“Nature sets the bar so high. Complexity, chaos and the structure hidden in nature. Painting for me is about how I make sense of what I see and how I find what holds everything together”

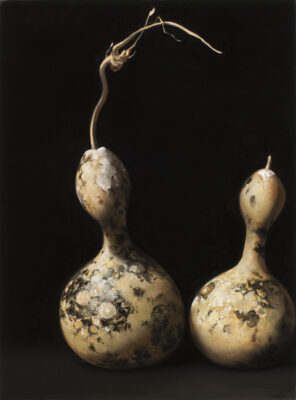

In the interview The Quiet Work of Looking, Gaela Erwin facilitates a conversation between Sheldon Tapley and Emil Robinson. Tapley, who taught Robinson at Centre College in Danville, KY, continues to be a significant mentor and friend to him. Many of Tapley’s still lifes, particularly his remarkable luminous gourd paintings, reflect the influence of 17th-century Spanish still-life masters Zurbarán and Cotán. Throughout the interview, Tapley and Robinson extensively discuss and contrast these painters, which leads them to explore deeper discussions about the essential elements they strive to express in their art.

Tapley states,

“I also think of the transformation of subjects as an ordinary responsibility of the artist: to paint something so that it is worth a second look; so that it might be affecting and memorable. Otherwise, we could look at the object and not bother with the painting.”

Emil Robinson extends this by saying,

“I am drawn to objects which mingle with an interior experience I am having. I trust my interior experience and have built it with respect and patience over my time as a painter. I notice elements of my surroundings and invite them to embody my intangible experience. Maybe that could be called “daydreaming”. Painting is my bridge between an internal world and the external world of objects.” This might be called vision. Whatever it’s called, it’s the place where I put my effort in hoping to become a better artist. I choose objects as a temporary home—a foil of sorts. Something seemingly sturdy but only useful to me if it can open into a painted world. My studio is a place of non-utilitarian logic—I like the paradox of looking right at an object but painting something totally different.”

Emil Robinson’s still life paintings blend realism with abstraction, transforming everyday objects into conduits of a more profound significance. These objects serve not just as visual elements but also as expressions of complex emotions and internal experiences. In his studio, Robinson delves into the creative possibilities of these objects, often resulting in works that depart markedly from their original appearances. His paintings achieve a delicate balance between meticulous, illusionistic details and broad swaths of vivid color, creating a visual link between tangible reality and abstract personal experiences. Robinson uses color as more than just a visual tool; it’s a medium for conveying psychological subtleties, with his painting process reflecting an ongoing dialogue between his studio environment and the external world.

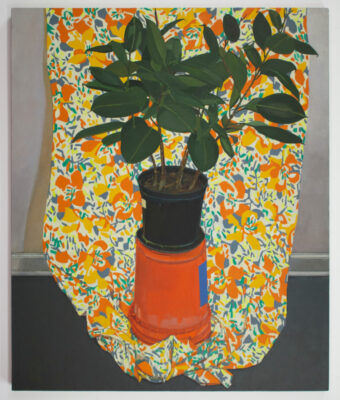

In the Painting Choices discussion, moderated by Matthew Lopas, artists Edmond Praybe, Eleanor Ray, and Joe Morzuch offer deep insights into their personal artistic journeys, each facing unique challenges and uncertainties.

Edmond Praybe speaks candidly about the periodic crises he experiences, questioning his artistic direction and the purpose of his work. He reveals how these moments of doubt are not only triggered by unsuccessful attempts but can also arise during successful phases, making them particularly perplexing and emotionally taxing. To manage these crises, Praybe engages in non-artistic activities such as hiking and reading, which help him gain perspective and remind him that individual failures do not define his overall artistic merit.

Joe Morzuch embraces the challenges of painting as essential to his growth, viewing each piece as a conversation that evolves and surprises him.

“Painting is hard.” he declares, “That’s why I like doing it. I used to be an athlete, and continued half way through college until an injury forced me to quit. Today, I lift weights and run long distance. I think it’s about reaching for goals I set for myself, each one a bit farther than the last. And coming to things consistently, with effort. I approach painting the same way. I feel defined by the goals I’m moving towards. They give me purpose. Even if, as with painting, those goals are sometimes abstract or less than concrete. I also just like being busy.”

Eleanor Ray states,

“I think I’m an outlier in this group here, in not working on single paintings for so long. If a painting doesn’t work out, I’ll abandon it, and often try a few more approaches to a similar idea or image. But I’m not always deciding whether something worked right away. The painting process itself is more self-contained for me, and I don’t want it to reflect a sense of struggle exactly.”

Ray highlights the importance of painting from personal experience, which brings authenticity and emotional depth to her work. She also discusses her shift from observational painting to using photographic references, driven by a desire to capture broader landscapes and memories. Together, these painters underscore the importance of resilience and self-reflection in navigating the complexities of the creative process, emphasizing that doubt and difficulty are integral to personal and artistic development.

It’s impossible to review every one of the book’s interviews and artists, they all merit detailed exploration and recognition. Several of the interviews feature artists who have also contributed to Painting Perceptions. John Goodrich, the designer of the Conversations book, along with Xico Greenwald and Neil Plotkin, have all written reviews and conducted interviews for the site. I’ve had the privilege of interviewing Tim Kennedy, Matt Klos, Matthew Lopas, Emil Robinson, Elizabeth Higgins, Paula Heisen, Edmond Praybe, Ken Kewley, Sydney Licht, and Nicole Santiago, all included in this book. My hope is to eventually have the opportunity to engage with many more of these remarkable painters, delving deeper into their artistic journeys.

Good review, Larry. Now I will look at the Zeuxis site.