Philip Guston, 1969-1979, At Hauser & Wirth (West 22nd Street) through October 30

Review by John Goodrich, guest contributor

Philip Guston (1913-1980), whose early Abstract-Expressionist paintings must be counted among the politest of that burly movement, had a way of rudely awakening us. In 1970, he famously startled the artworld with a show of coarsely cartoonish figurative paintings, served up in unluscious blacks and grayed pinks. The reaction from many quarters was fierce, and unkind. The critic Hilton Kramer questioned the very sincerity of the work in a scathing review, memorably titled “A Mandarin Pretending to be a Stumblebum.”

In these last couple of years, several decades after he last touched brush to canvas, Guston has again offended large parts of the art-loving public. This time it’s on account of the Ku Klux Klansmen that populate many of those same paintings from 1969-70. We inhabit today a more socially aware world, and it’s increasingly apparent how uneasily Guston’s characters – with their hoods, gloved bulbous hands and toy-like cars – straddle the divide between comic strip and political broadsheet.

Guston’s own politics have never been in doubt; his early mural denouncing the Klan had been defaced by the Los Angeles police in the early 30s, and in his later years he repeatedly claimed that the hooded figures were a kind of self-portraiture, and by implication, a form of brutal self-examination. But such a defense is unknown or insufficient to many of today’s gallery-goers, whose storm of protest prompted four museums to postpone a major traveling show of his work. The show has been rescheduled to launch in 2022.

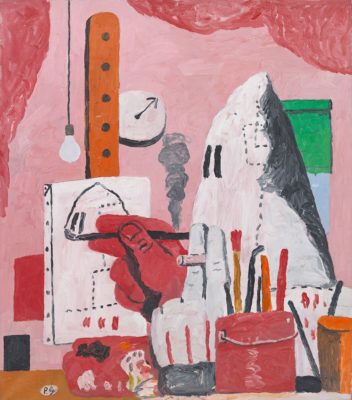

The Studio, Philip Guston, 1969 Oil on canvas, 48 x 42 in, © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Private Collection

In the meantime, we have “Philip Guston, 1969-1979,” the latest in a series of exhibitions of the artist’s work presented by Hauser & Wirth, which represents his estate. Assembled from museum and private collections, the eighteen paintings are spaciously installed in two large rooms. Six paintings featuring Klansmen – all but two on public exhibit for the first time – fill the first room. Indistinguishable from one another and gestureless (except for the occasional motioning hand), the hooded figures are inarticulate in the same manner as their accessories: the boots, boards with bent nails, the cigarettes gripped nonchalantly between vertical fingers. Guston, however, has imagined a new task for each of his low-functioning subjects. They ride together in a car, they converse, one even paints on a canvas in “The Studio” (1969), the most conspicuously autobiographical work in the show. Perhaps in response to the recent controversy surrounding the artist, an introductory walltext notes that Guston “…holds up a mirror not only to America’s racist past and present, but dares to examine his own complicity.”

My own expectations of the show were enormous, due to rave reviews and the near-ecstatic accounts of some colleagues — and also, unavoidably, because of the paintings’ backstory. What mix of tumult and fortitude could prompt such a swerve in one’s lifework – especially for an artist with as elevated a reputation as Guston’s? Problematic, provocative painting has been nothing new for the last half-century, but in their day these paintings were the work of an artist with nothing to lose.

But is possible that Guston was simply turning Ab-Ex’s energy – its appetite for a state of extremis, its reliance on instinct, grit, and elemental purpose – in a new, figurative direction? “Nothing-to-lose” had in fact always been part and parcel of the New York School ethos, and the Ab-Ex virtues of directness and urgency are evident everywhere in Hauser & Wirth’s exhibition: blustery in their attack, virile in their unprettiness, the paintings are not artful feints at artlessness, as Hilton Kramer would have had us believe. They are sincere – and while we generally expect more than earnestness from any major artistic discipline, it’s always counted for a great part much of Ab-Ex’s potency.

Blackboard, Philip Guston, 1969, Oil on canvas, 79 1/2 x 112 in., © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Private Collection

And yet, I felt a few pangs of disappointment upon entering the first gallery. “A Day’s Work” (1970) does achieve something of a weighty effect, with broad looping forms carrying the eye across expanses of canvas. Elsewhere, multi-layered brushings of barely-differentiated grays give a resonant depth to the simplest composition here, “Blackboard” (1969). On the whole, however, the Klansmen paintings on view lack the rhythmic conviction of forms one expects from Matisse or Picasso. Guston’s cars, robes, and gloves tend to circulate with equal, goofy aplomb, their forms defined through evocative textures and stylistic inventions rather than momentous intervals. In Picasso’s “Guernica,” one arrives, almost achingly, at an outstretched hand; here, a hand is the standard, good-enough resolution of the dilemma of body-torso-arm. There’s also an off-putting ease to Guston’s reliance on his repertoire – not only the hoods and cigarettes, but also the dotted lines called upon to represent, at various points, stitching, distant skyscraper windows, and even hubcaps. Thematically, the paintings may recall the brooding admonitions of Goya, but stylistically they’re closer to Ab-Ex-injected versions of the comic strip “Peanuts.” This means the shortfall in rhythmic intensity takes a particular toll; given the crossfire of subject matter and style, some gallery-goers might well conclude the paintings were as much a caper as a personal pilgrimage.

Bug on Wall, Philip Guston, 1977, Oil on canvas 74 x 116 in, © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Private Collection

The originality and bravery of these images are enough to keep one looking, though, and hopes are amply rewarded in the second room, where a dozen paintings produced a few years later, between 1973 and 1979, line the walls. The Klansman are gone, but boots, limbs, and hands remain. How they remain is crucial; in a number of these paintings, these elements combine with climactic resolve. “Bug on Wall” (1977) contains a minimum of elements–a brick wall, an open plane above, a kind of tray and what might be whip hanging on the wall, and, yes, the bug resting atop–but Guston’s brushy, overlaid colors give an independent density to each: wall swells heavily upward; tray concentrates our view at a one point; spikey bug focuses it even more concisely at another; the background releases limpidly behind. It all sounds basic, but the interactions of colors and lines never are simple, and here each pictorial event urges on the next, with momentous effect. More so than in the Klansman paintings here, Guston imparts nobility to his abject objects.

Ancient Wall, Philip Guston, 1976, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Oil on canvas, 80 x 93 5/8 in

“Ancient Wall“ (1976) takes the motif a step further, topping a similar but higher wall with multiple scrawny, bent legs. Rather improbably, a mass of boot heels covers almost the wall’s entire surface, while a single, heavy-lidded eye peers up from a bottom corner – a witness to the atrocities of the Holocaust? The image clearly emerged from a dark psychic place; it resonates all the more because of its pictorial resolve.

Equally compelling is “Solitary II” (1978), in which a lumpy red plain, extending up almost half the painting, leads like a molten field to a pile of shabby boots. Lit dimly by a single overhead bulb, and viewed from a low, mouse-like point of view, the homely boots take on a mountainous, tragically grand, aspect.

In such paintings, one senses the artist making use of all the powers of painting to convey a trenchant vision – and not through a process of significations, but of embodiments. Can any painting really do justice to the scourge of racism and the horror of the Holocaust? Can it in fact match the written word in conveying historic calamities? Quite possibly not, but the pictorial intensity of Guston’s brave late works remind us of what painting can do.

Leave a Reply