Interview conversation by Jeffrey Carr

Philip Geiger is a respected and highly accomplished painter known for his domestic interiors, landscapes, and figure paintings. Receiving his undergraduate education at Washington University in St. Louis and his M.F.A. from Yale University School of Art, he began regularly showing in New York early in his career and has shown extensively in numerous group and solo shows.

He is represented by the Reynolds Gallery, Richmond, Virginia, Hidell Brooks Gallery in Charlotte, NC and has previously show work at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in NYC, NC. with a solo exhibition there in 2007. His paintings are represented in several prominent public collections and have been reviewed by the New York Times, Art in America, ARTnews, and The New Criterion. He taught for over thirty years at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, Virginia, before retiring to his current home and studio in Staunton, Virginia. We met recently via a Zoom session to discuss his painting practice.

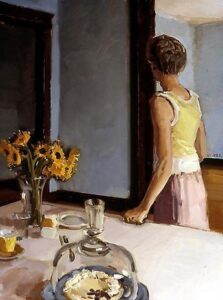

Jeffrey Carr: Phil, I just finished listening to a YouTube interview with you from 2012. You discussed how you revise your images heavily while working on them, and how you would sand or scrape down your paintings before repainting. Do you add figures and other elements into the picture? Do you do this from life? Or are you doing it from invention?

Philip Geiger: Well, both. I’ve become slower. I can work on paintings almost indefinitely by sanding them, by rethinking the composition. It’s not an efficient process at all, but I always have dissatisfaction with the image and want to work on it back in the studio for long periods of time. Then I might return to direct observational at a later date, trying to get something back.

JC: So, are the figures in these paintings largely invented? Do you use photographic references?

PG: Not much photographic reference. The process might change painting by painting and figure by figure. Some parts might be invented and some might be done directly from observation. I work from models several times a week. I schedule a model and work directly into the painting with the model. It always inspires me to work with a painting that I’ve already got going.

JC: So, you take a painting that you have already got going, and you may have sanded it down or scraped it. Do you then just sit somebody down in a chair and then paint them into the picture? Isn’t the space completely different? How are you able to integrate the new situation into the existing painting?

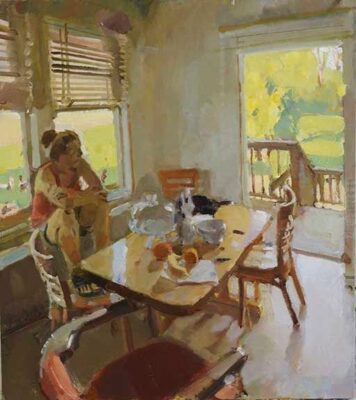

PG: I try to do that. I really like the accidents. I will oftentimes rethink the composition. The figure will be in some new place, or the scale will be new. Something like that. But that fight, that accident, of putting a figure into an existing painting that wasn’t planned in the first place, and that may even be in the wrong place, is really motivating. It can suggest something new that could happen in the painting, a new discovery. It’s certainly inefficient to keep working and searching like this. But I see the painting as a search. I’ve never thought that I could plan a painting in advance. I think I would be bored if I planned out a drawing and knew where things were going to go and then went at painting it. And in any case, this would be almost impossible if you work from direct observation because things are changing and the light changes.

JC: You’re telling me that you don’t work strictly from observation. You may incorporate a lot of observation but you’re working very synthetically. By synthetic, I mean that the process may involve a number of ways of constructing the image that is integrated into the final painting. The space in your paintings seems almost totally synthetic, rather than strictly naturalistic. But many of the details seem done from direct observation.

PG: They’re actual places, but I elaborate on them. I love elaborating walls in the studio, corners, moldings, architecture, and floors. In the studio, I sort of feel my way across the space to find some drama in the space, some meaning. That search is very slow.

JC: Do you mean that you find the drama and the excitement in the space itself rather than in the figures or situations being depicted? I remember seeing one of your paintings where you heavily reworked the image in order to create a certain effect of light across the walls.

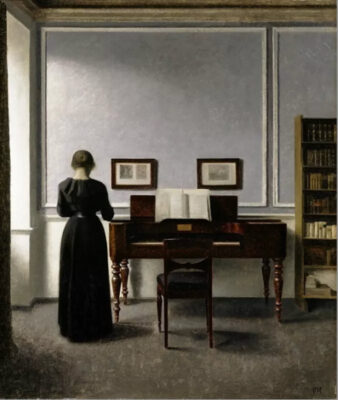

PG: The danish painter Wilhelm Hammershoi had this feeling for walls, French doors and the shadows cast by framed paintings or tables. He loved those things and I’m sure he worked them slowly. I don’t know if he worked them away from observation or not. But he seems to have elaborated on them. The richness seems important to him, the play of light across those surfaces.

JC: To me, it seems that in your paintings, as in Hammershoi, the depiction of space contains and defines the figures rather than just being a backdrop or a setting for the figures. This reminds me of the early Vermeer painting of the Woman reading a Letter. It was restored recently, and the wall behind the woman was removed to reveal a painting behind the figure. To me, this changes entirely the space and so the meaning of the painting. What was your response to this restoration?

PG: I like it less.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window c. 1657–1659, Oil on canvas, 33 in × 25.4 in, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

JC: So did I. Before the restoration, the wall behind the woman was densely painted and was very beautiful. It makes me think of your very painterly touch. Your paintings are not painted with a lot of detail; the detail is evoked rather than described. You don’t just copy; you evoke the form.

PG: That’s a great compliment. Vermeer has always been a touchstone for me in my work. He finds a universal quality in what was right in front of him, in that room in his house that he worked with over and over again. The same table and the same ermine coat and probably the same model. But he was able to find a density and emotion in these ordinary things. But his work is not figure-centric. I think of him as looking past the figure and zeroing in on the space between the chair and the wall, or a corner of a room where a basket is hung, or there’s even a nail on the wall. These events seem to attract him. The figures strike me as almost blank. I love them; they’re absolutely gorgeous. But you almost can’t know them. And in fact, there is a lot of debate about who was the model in his paintings; was it his wife or this or that person? Identities were removed from them, and the whole place is the drama.

JC: Vermeer did a lot of surprising and unexpected things with scale and size relationships. In one early painting, there is a girl sitting at a table, looking at a figure dressed as a sort of a Cavalier with a huge hat and with his elbow sitting out. The perspective is skewed so that he feels enormous while she feels little. You seem to do similar things with scale and size relationships in your paintings.

PG: I’ve never thought of that as a problem in Vermeer’s work. They just seem absolutely perfect to me; each of them is perfectly felt. In that one called The Laughing Girl, every bit of it seems so right and so felt that I don’t think too much about the space or the drawing in them. He did like to layer a dark foreground against a lighter passage or a silhouette shape.

JC: I think that this is true of your work as well. Expressiveness is created by the scale, the space, or even just the way a wall is worked. You create drama with people walking into a room or walking towards us with another distant figure silhouetted against a window or over in the corner. You really feel the drama in the space. Another artist who does this is Edward Hopper. Hopper’s painting evokes some indefinable meaning that you want to think comes from a figure or some other element in the painting, but it’s about something else. It’s about the way he puts together the space.

PG: Yeah, it’s about him. I think both Hopper and Vermeer have a feeling for shapes that is unique. I’ve tried to do that. To feel the proportions of the divisions inside the painting as having meaning. I often think of Vermeer as being the greatest shape maker. Just the amount of a map against a white wall just seems so right. The intervals feel deeply meaningful; it is the measures in between intervals in the painting that makes shapes.

JC: I’m thinking about Mondrian, who like Vermeer had this incredible sense of interval, where everything feels perfect. But Mondrian made his paintings about just those measurements and took out everything else.

PG: That’s never as interesting to me as the shapes in Vermeer. I wonder what Vermeer would have said about this. Would he have understood our language of abstraction and of trying to see shapes independently? Was it all intuitive on his part? I wish we could ask him. But you are right; they tried to separate that out in the 20th century. The shape intervals in Mondrian don’t do much for me.

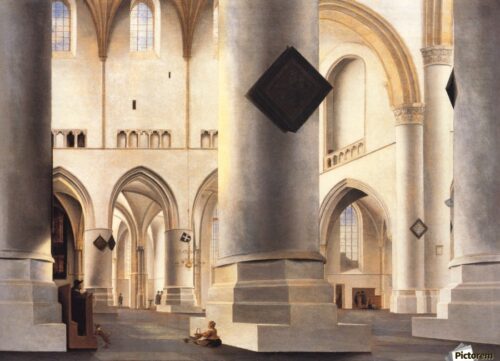

JC: I don’t think painting got any better by trying to be reductivist. For example, there is Saenredam, the dutch artist who did very severe white Church Interiors. Like Mondrian, he had a severely abstracted visual sense. But the intervals and shapes of his church interiors also create emotional responses and even ideas about divine light or reason or probity. By contrast, artists like Mondrian aspire to be purely abstract. But that’s obviously not what you are doing. Are you interested in creating mood or emotion through the use of space and the interactions of shape?

Pieter Saenredam (1597 – 1665), The Interior of the Grote Kerk at Haarlem (1636-7), Oil on oak, 59.5 × 81.7 cm, National Gallery, UK

PG: I don’t know what I would say about mood because I couldn’t identify what it is. But I have emotional reactions to what I would call rightness in a painting. That’s why I struggle with it for so long because it isn’t always there. I think that the communication of an interior life that comes through a painting is why we are interested in them. It’s something I struggle with, and I think it results in a mood. I am obviously attracted to very muted colors. In my mind, muted tones are more suggestive of light than brilliant, local color. And that, as well as an emphasis on value in my work, might create a mood that is different from other kinds of painting.

JC: There’s an old idea that color creates moods: brilliant color creates strong emotions and muted, quiet colors create quiet emotions. That might be true, or it might not. Like you, I’m not even sure what “mood” means. The early work of Degas uses low saturation color. He keeps the vividness and the intensity down. Perhaps because of his use of low-saturation colors, his moods are almost indescribable. The color-moods of Degas remind me of your paintings.

PG: There’s a kind of shimmering beauty in his work that I would describe as being figure-first. His figure drawing is so good that the presence of the figure is always the point of the painting. What he does around them is something to complement the figure and the movement of the figure. It’s a great challenge for me because I don’t draw the figure that well; nobody does. I love looking at his work.

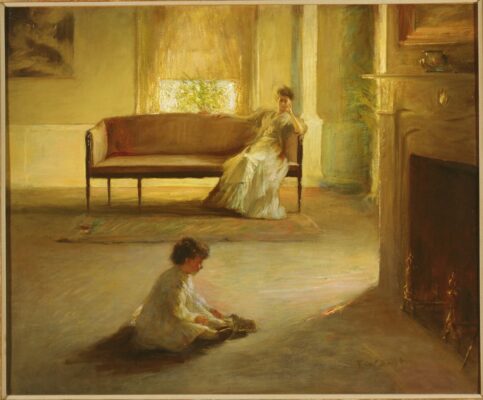

JC: Your pictures are often enveloped with a light I’ve seen in interiors done by other American artists like Thomas Dewing. There’s a warm, enveloping glow to these paintings in which everybody exists in a liquid, enveloping honey-colored glow. Do you feel any connection to the many American artists who paint quiet, tonalist interiors, artists like Tarbell or Decamp?

Edmund Charles Tarbell (1862-1938), Interior with Mother and Child oil on canvas, 25 x 30 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

PG: Well, it does look like that. I see the similarity but I don’t look at those artists very much and I’m actually not very familiar with them. Someone from that time period that I certainly do look at is Vilhelm Hammershoi. I feel more connected to that painting. All those Boston painters like Bensen or Tarbell never challenged me enough, I guess. They are not as challenging as looking at a Degas. Degas may be doing very different things, but it’s a real challenge to me. I’ve always got a Degas book there in the studio. I’ve got the Hammershoi book there, and the Vuillard book. Those are the books I might look at every morning. I do see the similarities with those other painters; there might be a Merrit Chase who would do a beautiful floor or a beautiful sofa. But I’ve never looked at them much.

JC: You are mentioning some classic European painters like Hammershoi and Vuillard. But to me, there is something quintessentially American in your painting, and I’m trying to feel where you are in this spectrum. I sense a relationship with artists in our tradition, like Edwin Dickinson, for example. How do you connect with someone like that? And we talked about Hopper.

PG: Well, Hopper for sure. I’ve made a huge study of Hopper and I’ve spent a lot of time painting outside. I’ve looked at all of his works very closely and I respond to Hopper a lot. I love Edwin Dickinson, but I don’t quite know what to make of it. I think there’s a great mystery in his work and some real originality in what he did. The extreme tonalness and greyness of the work are attractive to me. It seems almost romantic; his meditations on funereal subjects and death.

I find him fascinating, but I haven’t found a way to make a lot out of that. Everybody looks at his self-portraits and wants to do some self-portraits. I’ve done that, maybe inspired by him.

JC: We’ve been talking about historic painters. But you and I came of age in a vastly different artistic universe than the one that exists now. What are some painters of the seventies and eighties that you feel a real kinship with?

PG: My teachers William Bailey and Lennart Anderson remain models for me. I admire what they did in their work. Both of them pursued their vision whether the artworld paid any attention to them or not. They pursued their vision fearlessly their whole lives. There was a recent exhibition of Lennart Anderson, and he’s getting some attention. I love his work, and both of their examples are important to me. There’s a painting that was the centerpiece of the recent Anderson exhibition that is owned by the University of Virginia. It’s called St. Mark’s Place. It’s an early New York street painting with three main figures. One figure is leaning from a pole; he painted that by looking at himself in a mirror. Another figure is a man with a dog, and there is a woman looking back. I looked a lot at that painting when they would hang it in the 1980s, and it had a big impact on me. The putting together of these three figures implied dense psychology. They seem to be aware of each other, even though they weren’t interacting or doing anything together. The University of Virginia also owns the William Bailey painting called Portrait of S, which is based on a Balthus. Both of these paintings were important to me, and that was a moment in time that was important. Bailey would say to his students, “Don’t be afraid to be influenced by other painters”. He obviously felt that looking at painters like Balthus or Courbet was perfectly legitimate for artists to do, and to make a variation on something like Courbet’s Women in the Grass. I’ve always liked this example; it seems to free me.

Lennart Anderson, St. Mark’s Place, 1969-1976, Oil on canvas, 93 13/16 x 74 1/8 in.© Estate of Lennart Anderson Courtesy of the Fralin Museum of Art.

.

JC: Painters often have their still life objects all around the studio, and arrange them into compositions to paint. There are several great Lennart Anderson still lifes like this. But William Bailey once joked that he had all of his still-life objects in his pocket. I think he meant that his still-life objects were more invented than observed, and were more about purely formal visual relationships than about actual objects. Bailey’s meticulously painted backgrounds even make me think of a Brice Marden. In painting like this, the subject matter is often just a pretext. Do you think of yourself as mostly a formal painter, looking for formal solutions? Or do you see yourself in some other way?

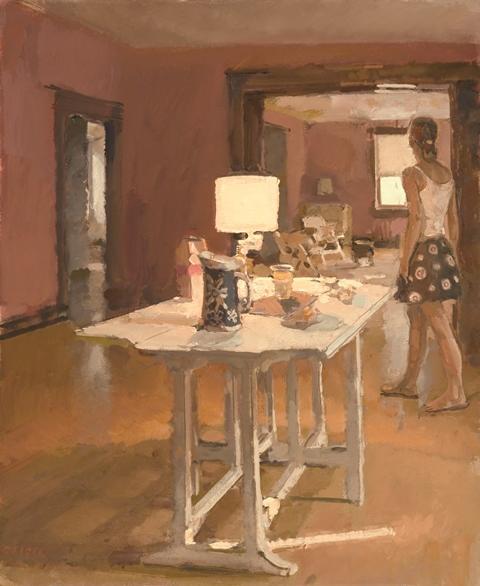

PG: I don’t want to be a formalist. I would be an abstract painter if I did. I am in love with the real world. I think that it’s a great starting point for making a painting. I want it in there; all of the rich complexity and interpretive possibilities of subject matter. I have an affection for people and I want to get that into the painting. The places we live in can reflect our interior life and are part of it. I think that’s worth highlighting and making paintings about. The world in front of us is a really rich subject; our lives, our houses, the town I live in, my life. I think the ideology of modernism has dried out painting. It became reductive by trying to make it just about the elements of painting in a more and more pure way. I think all this rich accidentalness of our lives, and the fact that we psychologize paintings and see ourselves in paintings and identify with paintings and have emotions about the figures in paintings, is all a necessary part of the richness.

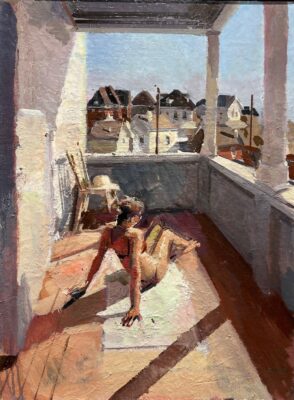

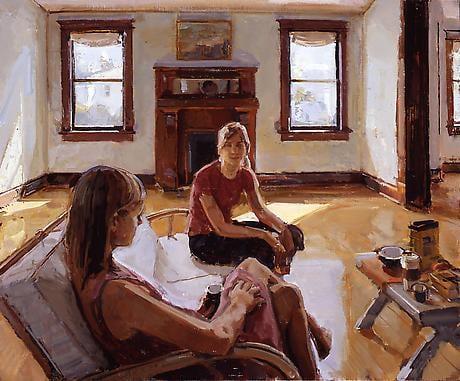

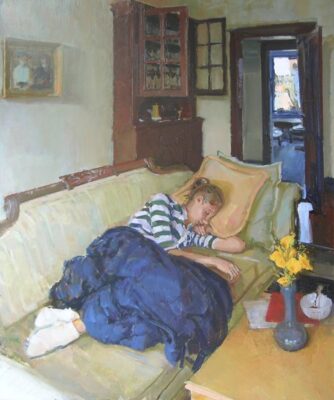

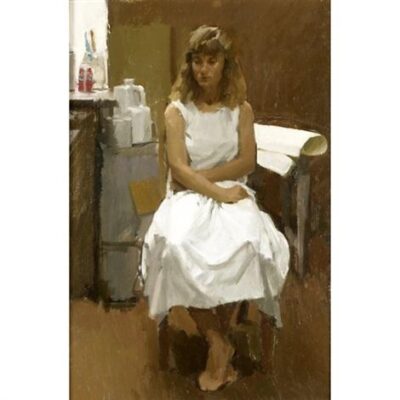

JC: A lot of the paintings I see by younger artists reflect gender or racial concerns or are satirical, ironic, or humorous. I’m told that younger artists often feel their art should address social or political issues. Their subject matters are often very witty or even alarming. But the subject matters of your paintings seem very quiet and understated. I think of an artist like John Koch who paints similarly understated subject matter. You depict young women sitting quietly at tables, women sleeping, figures moving through a room, light flowing over a figure from a window, or the occasional suburban landscape. And you and I both frequently depict women in our pictures. That men often depict women has been a source of controversy. What is this about?

PG: Just to address that issue, I see my paintings as celebratory. I know there is some critic out there who won’t see my paintings that way and could interpret them with some dark story, but I see them as celebratory. I love who it is that I’m painting, either men or women. People in places is a subject that suggests an opportunity to make a painting. I like the kind of space of figurative painting where you don’t know exactly what is happening. Those are evocative to me. John Koch’s work can be at times a bit literal. In Koch’s painting, we know what is happening. I like the surprises and accidents in painting, where we get to make our own meaning; the idea of a picture about being in between things happening… or when something has just happened, or is going to happen and it’s not defined. This open endedness fires my imagination.

JC: In your paintings, you might have someone at a table, and there might be some objects on the table. But it’s not a depiction of a table after breakfast, a conversation, or some other very specific event. I remember a painting of yours with a deep space in which there is a silhouetted figure, but it’s never a story about somebody opening the door and welcoming the guests. You never seem to tell little stories in your paintings. As you said, they’re very ambiguous. They aren’t people just posing, but at the same time, there isn’t really a story in there that I can discern.

PG: As for myself, I sometimes see a kind of conversation or correspondence between elements. I want to have the appearance of a real place. This is why I don’t paint absolutely anything. I want the environment to be clear – this is a dining room – but the situation to be less clear. So I will do a chair and a person or a flower and a person or a window and a person, and I will put these two things in a relationship with each other that would be surprising, an imaginative association or non-sequitur. The person and the junk on the table; you bounce between one and the other. And they begin to have something to do with each other or belong to each other in some way. Those are the kinds of things that interest me as I’m setting the painting up. Does the back of that chair relate to the figure, so that it will be dramatic enough that we move from this to that? Without it being a literal narrative, these pairings would seem to me to suggest a kind of meaning in the setup that would be surprising. I see that in Vuillard, where a figure will be placed somewhere you don’t expect them to be in the painting. He’ll make us really contemplate a big old chair in the foreground, and he makes us really study it. There will be some pattern on the floor, and he’ll make a lot out of it. The chair or the floor become as interesting as the person. This is very appealing to me. This multiplicity distinguishes an image from a portrait, it’s now an interior drama.

JC: I remember a Vuillard painting with a woman sitting, as you said, in a little corner of the painting. He put a little orange piece of light on her nose and you end up looking at that as much as you do at the woman.

PG: It’s indirection, I like indirection and painting where you see something like that. We were talking about Degas, where he will have some model bathing but then you’ll see this pattern that he’s layered in the background that’s absolutely musically beautiful with layers of warms and cools laid upon each other. You leave the figure to look at this pattern. It’s a kind of indirection in making the image.

JC: With Degas, it is always the unexpected scene. Instead of the model facing you, you are looking down at her back from a high point of view, so that it is an unfamiliar view. In the great painting of the Belelli family, Degas depicts a mother and her little girl staring off into space while visually being separated from the figure of a man sitting to the right. There is a division right between the two areas of the picture. Lennart Anderson’s Street painting is also dramatic, maybe his only example of doing this. The painting has that wagon tipping over with people running, and the girl coming out of the door with her mouth open. Have you ever painted something that was deliberately dramatic or making a statement in that way?

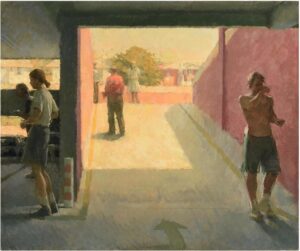

PG: Well I think of the light as being dramatic, and I’ve painted some very dark paintings in which people are definitely in shadow. Lennart Anderson painted a man in midair jumping out of a building in what I guess was a suicide. I can’t imagine doing that. I’ve never done anything like that, starting with something as literal as that. But I like the idea of divided paintings, like the Degas painting of the Bellelli family. Paintings that divide themselves into parts with people doing different things in different parts of the painting. That suggests a drama that may be less dramatic than a divorce but suggests an attention or awareness across the space. I like the idea of dividing a painting in half and having two sides.

JC: You have a painting of a guy coming up out of a stairwell towards us on the right side of the painting, and right across on the other side of the painting is a deep space with people continuing to a distant window. This is creating drama with space and light and pictorial organization, and not with dramatic subject matter. This is like what Degas does. By contrast, there are lots of contemporary artists who are doing wonderful work with very dramatic subject matters; wildly inventive paintings, sexual satire, and social commentary. Seemingly everything except straightforward depictions of their immediate environment. What do you think about all that?

PG: Well, it’s just not me, you know? I like the idea that art doesn’t have to be all the same. We all don’t have to do the same thing. The examples we’ve been talking about are what I’m most interested in. I have great respect for those other artists but it’s just not my temperament. I can’t imagine doing something like that. I think of the subjects in my work as being much quieter; not operatic or extremely dramatic. I like Hammershoi or Morandi. Something as quiet as that: just the relationships of this object to that object seems very meaningful to me. I’ve never thought of painting as being a great vehicle for social commentary. Some people can do wildly expressive paintings with heavily loaded subject matters. But I think this can also get you drawn away from what is really most expressive in painting.

JC: How important is content for us painters? There’s a show up now of Philip Guston, an artist who addressed socially relevant and controversial subject matters. Do we have any kind of responsibility to make socially-conscious paintings? Are paintings made for an audience, or is it just Art for Art’s sake?

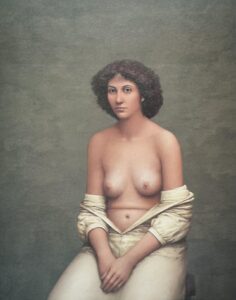

PG: I don’t quite agree with the dichotomy that you’re setting up here because I am very sympathetic to work that wants to have a moral core. I think painting that pursues beauty in the quiet sense that we are talking about is maybe the most moral kind of painting. Paintings that might deal with topical issues like the Guernica, for example, are just very different. It’s not my temperament to do the Guernica. But I think that pursuing authenticity and beauty in the quiet way that we might associate with Vuillard, someone who didn’t leave his apartment much, who painted his direct surroundings, is as morally engaged as Picasso’s Guernica. I think Vuillard is searching for a form of the Good. He’s making a proposition about the form of the Good that ends up being more universal than the Guernica. I think that there is more than one way to have a moral core to the activity that we are doing. I don’t like this dichotomy of it being either Art for Art’s Sake or it being like the Guernica, addressing war and peace and current events. I think the great thing about the art world now is that you can pursue one or the other, according to your temperament. We don’t all have to do the same thing. A painter like Ingres, for example, has dug deep into his ideas of beauty and interior authenticity as it is connected to beauty. That’s one of the greatest achievements an artist can make and is one of the most moral contributions an artist can make. I think Ingres did something new by extending human awareness and capacity in the pursuit of what he did so successfully. I wouldn’t want to compare myself to Ingres. But I admire that as much as I admire Picasso painting the Guernica. I think that in the long run, it may mean more.

JC: You’re equating Beauty and morality.

PG: Yes!

JC: And that beauty itself has a moral force.

PG: Yes!

JC: I’m going to ask you something which I think would provoke a lot of painters. Is your subject matter about beauty?

PG: I’m trying. I think I’m trying. I think that that’s the connection. It’s absurd to compare myself to Ingres or Degas or to their great achievements of beauty. But that is what motivates me. That is what gets me turned on to make a painting. We’re connected to that. Why else would you go through all of this if you don’t get to be in proximity to beauty? It’s not very good as social commentary. Hopefully, we give it a new visible form that you can communicate with somebody else. I think that’s at the center. We wouldn’t be going about this backward sort of activity for any other reason.

JC: That’s a perfect ending Phil. Thanks for sharing your insights and experience and for your wonderful paintings.

Thanks for this interview. I particularly appreciated his comments about beauty. Perhaps, though, there’s a typo in the last line of the long paragraph above the “House” painting: the first “admire” should be “admit”?

Yes, the last few comments about beauty are so stirring and important. A really great interview overall.

Excellent interview of a wonderful and generous artist!