I’m pleased to share this interview with the fabulous Belgian painter and pastellist Mathieu Weemaels where he talks at length about his background, process, and thoughts on making his many still lifes, interiors and landscape. I want to thank him for his generosity in responding to my email interview questions. Mathieu Weemaels is not a native English speaker, and the interview is edited for clarity and brevity.

Much of Weemaels artwork reflects his incredible talent as a draftsman and pastellist. His naturalistic sensibilities respect the world as he finds it and seeks to find the most compelling pictorial truths. Keen observation combined with the right abstraction for a selected view of commonplace household items staged to both surprise and delight us with his contemplative visual poetics.

Mathieu Weemaels, born in 1967, Lives and works in Brussels. He is represented by the Galerie Olivia Ganancia in Paris, France; Galerie Ducastel in Avignon, France; and several other European galleries.

Larry Groff: Can you tell us something about your background? What were your early years like, and how did you become a painter?

Mathieu Weemaels: That’s an important question to me because of the many reasons for me to become a painter. I was always drawing as a kid; when I was 6, I told myself: drawing is it for me. I wanted to find answers to the big questions of life by drawing and painting. In a way, I felt it was a way to discover and understand things.

I come from an artist’s family. Musicians and painters. Not always professionals, but art was in the air. So thinking about art as a professional project wasn’t considered something eccentric or downright crazy. Quite the opposite, it was just a normal choice. When I was a teenager, I wanted to become a cartoonist, absolutely not a painter. Then around 20, I completely changed my mind after a difficult period I’ve been through, and I came back to my original wish in a way: answer the big questions of our existence through drawing. I always say drawing because I still didn’t want to be a painter. I “hated artists” :-). So I started to explore pastels. It was a way to be a drawer and a painter at the same time. I’ve been “painting” with pastels for years until 2000, when I started to use oil on canvas. It could seem just a difference of technique, but it’s more than that as painting allows a much longer work. In my own experience, pastels were at their best when done quite quickly in a kind of natural energy. However, oil becomes, in my own practice, more and more interesting when worked during very long periods.

LG: Where did you go to art school, and what was that like for you?

Mathieu Weemaels: During the school years, I mean, until 18 years old, unfortunately, I had no art teaching at all. I just went to a normal school, continued to draw at home, with the occasional help of my father-in-law, a French teacher who drew a lot. My father was a painter, but I didn’t live with him, and he is an abstract and geometric painter. I was not very interested in that aspect. I wanted to learn how to paint “real things,” not squares and other geometric forms. But nobody taught me at that period, and I regretted it many times. I started in an art school at 18, to become a cartoonist, as I said. I later changed my mind and stopped after one year or two and decided to go to another art school, La Cambre, in Brussels. I went into the drawing classes ( not painting ). That’s where I started to use pastel and where I met for the first time people who were spending all their time on art as an expression of their deep personalities. It’s been a very new and exciting experience for me to discover that. But after two years, I also stopped.

LG: Did you get any traditional academic or figurative training? I’ve read that you were largely self-taught. What was your experience with this?

Mathieu Weemaels: No, I had no traditional academic training at all. In the cartoon school where I’ve been, I learned to draw without being too traditional, and I learned to draw the objects by outlining the background, for example. It was another way to draw that I didn’t know before and that I never forgot. But making cartoons is not just drawing. There are many other aspects specific to that kind of creation. And little by little I wanted to focus on drawing only, for itself. So I changed direction. I entered art school when I was 20. It was not the kind of school that taught academically. I regretted it, but that’s how it was. The teachers expected us to become artists in our own way: find our means to express ourselves, our universe to be in. No matter the technique. But even if I liked that aspect, if I found it interesting, I also wanted to continue learning to draw real things, learn to observe and paint, and it was not the thing to do there. So I stopped too, after two years once again. I definitively stopped school and started to draw by myself and learn to observe—observation as a way to understand the world. Just being as neutral as possible, see things as they are. I had in mind the incredible work of Lopez Garcia. But I also loved the expressive and original universe of a painter like Francis Bacon.

LG: Belgium’s long history includes hugely important painters such as Jan van Eyck who practically invented oil painting. Other Flemish painter luminaries include Paul Rubens, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hans Memling, and many others. Today, are there many Belgian painters working from observation? How accepted is naturalistic or observational painting in the art world there?

Mathieu Weemaels: Wow, another excellent question. Unfortunately, in Belgium, like in many other parts of the world, observation is not considered extraordinary. When visiting official exhibitions of today’s painters in Brussels, I often thought that it was as if they were excusing themselves to paint. Like a voluntary wish of the destruction of the natural richness and beauty of painting. I found it most of the time extremely sad, poor, and not interesting. Art with too much intellect and no heart. Art without risk or generosity. I don’t mean the abstract painters, who play in another category and can often be good. But most of the time, the figurative painting I’ve seen was inferior not just because these painters weren’t good, but also for an inability to talk about beauty in their work. As if beauty was inappropriate for a painter of our century, the painter has to be strange or bad to be considered interesting. It’s one of the reasons why I loved discovering American painters, Israeli painters, etc, on Facebook.

Of course, I didn’t like them all, but I was excited to see all the painters who know how to paint! And they brought new ideas, new visions, with affinities to Antonio Lopez Garcia and others. They didn’t necessarily paint like in the 19th century, but they respected this heritage instead of rejecting it. We have a beautiful painting tradition in Belgium, but its destruction is almost complete, except for a few holdout painters who still resist. Some less famous painters of the 19th and 20th centuries in Belgium are also very good, like Ensor, Spilliaert, Khnopff.

LG: Who are some of the Flemish painters you most love and who have influenced you in some way?

Mathieu Weemaels: Rembrandt. He is not Flemish but Dutch, but it’s a close and similar culture. He is my complete and eternal hero. I love his technique, of course, but I also love what he expresses. The religious and spiritual feeling in his work. The strength of his work combined with the dramatic aspects and profound humanity.

He influenced me when I started, but I felt unable to become as good as him as I started too late. Despite only being 20, I was thinking I was already too old compared to what Rembrandt was able to do at that age. I was just starting to really try to do good things. So although I was still young, I was already old. I was very jealous when I saw the paintings he made when he was very young. I regret that my parents didn’t make me start earlier, like him in the studio of a painter.

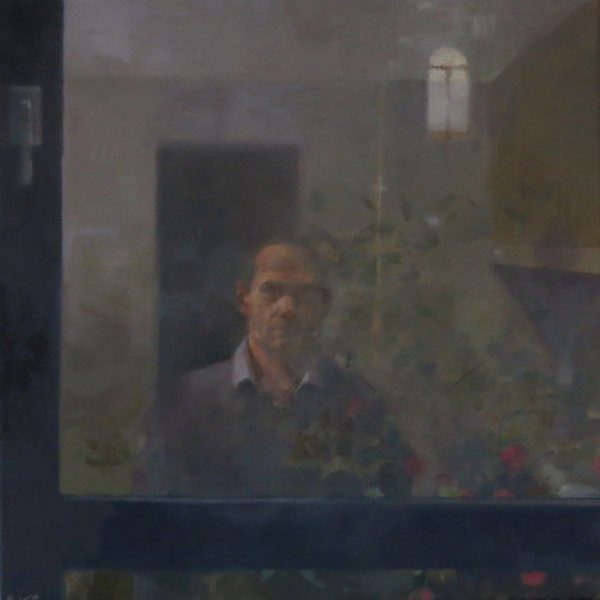

Self portrait, at age 20

Other Belgian painters interested me but never as much as him. When I was 20, I could spend hours in front of his self-portraits during a tough period for me, with the intense feeling he was talking to me. I had a special feeling about his work, something I never had with any other painter. But for my work, my first influence was Lopez Garcia. After my chaotic school years, when I started to paint for myself, I thought: what am I going to paint? And I felt Lopez Garcia, who just painted mundane things around him. So I started to do the same: paint my familiar universe. And little by little, it evolved.

LG: What painters would you say have influenced your work the most?

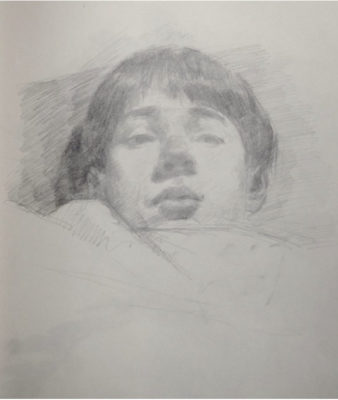

Mathieu Weemaels: It depends on what periods of my life; as I mentioned, Lopez Garcia, for the first years, has been the starting point of my work. Observation, mundane things and scenes, nothing special, just the world as it is. Just paint my ordinary life. Then I had a big love for Lucian Freud (despite previously not liking him) in early 2000. After seeing an exhibition in London in 2003, I started to draw nudes (always pastel). I always dreamed of “painting” humans, but I never found a way to paint them. Why? I had in mind some pastels of an earlier teacher who made figures in movement, a bit like in Caravaggio’s paintings. But it seemed too complicated to reach a high level of perfection. So seeing Freud’s nudes opened a door for me, and I thought: so much is expressed with just a model on a bed, let me start that way too. The first ones were in the still of Lucian Freud, but it eventually evolved into my current approach to working with nudes. I think one can immediately see the influence of Freud, especially for the first ones, but I developed my sensibility, my concerns.

Later, I discovered “FB painters,” and it’s been a fantastic new source of inspiration. Or, I would say of stimulation. Seeing all these painters loving the same references as me: Lopez, Bacon, Freud, etc., has been fantastic food for me. Thanks to them, I discovered many interesting contemporary artists, famous or not famous, like me. Sharing ideas with them continues to be a fantastic experience—different from influences of masters, as for once, I could talk with them.

LG: Do you paint only from life, or do you use photos, memory, and drawings as well?

Mathieu Weemaels: I almost always paint from life–with no preparatory drawings. The ideas come from what is around me: objects on a table, roofs through my window, my garden, etc. I see the painting in my head, and then I paint. I don’t feel the same emotion from photos. I’ve tried this, of course, but I never appreciated it. As I never felt the same feeling, I got from painting from life. The problem is that painting from life means explore all the subjects around me. It needs to be very inventive after years of painting the same things. How not get bored and find the same desire? Photo allows me to paint other scenes, but they don’t make it for me.

I have used photos from time to time, especially for landscapes. I took the photos during my holidays, and I used them for paintings. I used small, poor-quality images as a starting point for a painting that would then depart to discover its own reality.

These days, I discovered a new pleasure regarding memory. I start with the subject in front of me and then finish it from memory once I know the subject very well. This more subjective approach is free from being too focused on the reality of the original model and more on the reality of the painting itself

LG: Can you tell us something about your process? How do you go about beginning a painting?

Mathieu Weemaels: I just answered this question but I’ll expand on this further. When I work in my studio, I use the objects I have there; a mirror, a coat, old flowers, a table, a bowl, etc. And I put them here and there until I find something that inspires me. Frequently, I’ve been using mirrors to create the scenes to paint. They reflect reality and create unexpected still-life possibilities that have an abstract feeling that I find interesting. I never appreciated still-life paintings as a younger painter. Even Morandi, who some people have compared me to, has never been an example for me. As I said, I’m focused on my way of painting still-lives or not still-lives is not the point. Painting as an exploration, traditional still lives never interested me that much

So, once the scene is there, and I feel it could make a good painting, I start on the canvas ( or on the paper when I worked with pastels ), and I put down the main lines directly with my brush to see if it works, if the idea was good enough for the painting. I’ll often focus on a detail or paint just a part of the objects, keeping them partly hidden by the edge of the canvas. And then I paint….and paint, and paint. I almost always change things during the process. Adding or eliminating objects, following my instinct. I love to alternate observation moments and working away from the subject. As I said, it allows me to let myself drift like a boat without an anchor. If it’s necessary, I come back to observation later. Or, as Japanese artists did: I look at the subject with intensity and then use the information to continue the painting without the subject in front of me. Painting is a way to observe life with insight and intensity, so the fact of painting a subject has the effect of knowing it much more than if I didn’t paint it.

For other subjects, it depends. One day, I discovered that the flat roof I see every day when I go to my studio was a splendid subject because, after a rain, the water reflected the sky, the houses. Suddenly I saw its beauty and started a series of paintings on that subject with the same technique as I’ve been explaining. I don’t often leave my studio for different subjects, but I love it when I do, like with a series in my bathroom ( again, the influence of Lopez Garcia and Bonnard). I wanted to paint the silence of the water in the bath.

It’s also been the same process for the nudes I’ve made: let the model move until I find something that could make a good painting. And then start, allowing the painting to evolve, ideas change, and working from observation or not. An important difference between pastel and oil is that my pastels tend to be faster work. With oil painting, I work again and again on the same painting, sometimes taking months or even years. Another essential concern is that I almost always use natural light.

LG: What makes you decide whether to use oil paint or pastel when starting a picture?

Mathieu Weemaels: Deciding between these two has tortured me for years. I felt I was better at pastel, but I wanted to explore oil. So what to choose? Efficiency and production or adventure and experimentation? Over the years, I made a kind of 50/50 proposition to continue to finish some works ( mainly with pastels ) and let me the opportunity to improve oil and find my own way to use it. Now, my pastels are sleeping, hoping I’ll use them again one day, and I still use them from time to time, but it’s really oil that is 99% of my actual work. And I love it, and I start to feel comfortable with this technique. Like I was with pastel, I didn’t have to think about the technical aspect, as it came naturally, like a dog naturally following his master. I don’t choose what technique to use by the subject matter; instead, I choose a way to paint.

LG: Is capturing your first impressions of a view or still life set up something you try to hold on to throughout the painting, or do you tend to leave the composition more open, allowing it to evolve with the changing light, mood, etc?

Mathieu Weemaels: I always let the painting find its own way and reality. So it very often changes a lot during the process. It was not like that with pastel. I didn’t change that much from the initial idea. Just technically, it was almost impossible as the paper gets “tired” and the feeling of light with pastels disappears little by little. But now I sometimes change a painting after an exhibition if I consider it not resolved enough.

LG: In many of your compositions, there are solid abstract 2D sensibilities. Fairfield Porter once said that: “In representational painting, one must look for the abstract and in abstract painting, one must look for the subject.” What are some of the ways you look for the abstract in your paintings?

Mathieu Weemaels: Since the beginning of photography, painting has lost one of its reasons to exist: to represent things as they are. A city, a king, a woman, portraits, etc. Of course, this is an idea I’ve heard many times. You know, “painting is dead”, Malevitch, etc. I’ve listened to this for years when I was in art schools. It was impossible for me just to take all these ideas and put them away, to paint like painters of the 19th. Whatever one thinks, a painting is first of all, colors, lines, and shapes on a flat surface. Nothing less, nothing more. Of course, it’s much more, but it’s also probably the reason why you see a 2-dimensional aspect. I didn’t especially make it consciously, but it was undoubtedly in my mind during the process.

I remember one lesson very well, in particular, during my cartoon school years, the teacher was explaining a painting of Matisse. He explained how he voluntarily “destroyed” all the perspective effects—bringing an intellectual dimension to his work. Playing with the vocabulary of painting and changing the rules. ( perspective, lighter colors at the background, etc) I never forgot that lesson. I found this very interesting. So, it probably left some trace in my way to work.

LG: Do you need to paint in silence and isolation?

Mathieu Weemaels: Most of the time, yes. I need silence and calm. I love that.

LG: Does listening to music help your painting or interfere?

Mathieu Weemaels: It doesn’t help. I sometimes want to listen to music, but I don’t think I could seriously finish a painting with music playing. I need calm and silence. However, music can be ok if I don’t have to think too much.

LG: Edgar Degas was a great pastelist who reportedly said: “Painting is easy when you don’t know how, but very difficult when you do” he later said: “Only when he no longer knows what he is doing does the painter do good things.” Do you ever find that your high level of skill in painting can work against you? Why is that?

Mathieu Weemaels: This question is very interesting. I often quote this sentence of Degas as I find it brilliant and absolutely true. When one has to learn the technique, it can be difficult, but in a way, the comfort it brings is the most terrible thing. Perhaps a more terrifying and critical question is: why do I paint? Once the technique is ok, it becomes difficult to avoid this question.

This brings me to explain something else about the fact to switch from pastel to oil. I felt too comfortable with pastel. I could go where I wanted to go. Well, in certain limits, it worked quite easily for me, and the results came with a particular facility. Oil didn’t have that seductive aspect. I was not so self-assured. I felt like an acrobat, used to perform beautiful figures and have some applauses for that who suddenly decides it’s enough and searches an uncomfortable situation because he feels it’s the only way to evolve. Working with oil allowed me to explore a new dimension of my work and of my soul: the meaning. Less skill, more meaning.

Painting with oil was a way to feel lost, without my usual landmarks. Becoming may be more artist than the drawer. I used to say about myself for years: I am not an artist. I am a drawer. And it’s true, I loved drawing but had no specific message or thing to express. Now that I decided in a way to “break my tools”, I’m becoming more of an artist. This means less dependence on the image and more about something else that is stranger, scarier, and difficult, the deeper I get into something I don’t know. Now when I paint, I let things happen. I put myself aside, and I let things happen. Hoping they’ll surprise me. It was a bit like that with pastel, too, because I didn’t think I could just let things “happen” without me as I do now.

LG: I’ve read that Degas (will link; https://blog.phillipscollection.org/2011/12/20/degas-and-pastels-part-i/) found his pastels more salable and made many small pastels that helped him “to earn my dog’s life.” He created over 700 pastels and experimented with using pastels in a number of novel ways, such as using steam, water and even placing a drawing on the floor covered with a board and then crushing pastels into the paper with his foot for a particular effect. I’m curious if you similarly experiment with your pastel work or make your own pastels?

Mathieu Weemaels: I’ve often experimented with my pastels. I’ve always made them by myself, from pigments. So I could have an outstanding quality of very thick and soft pastels. They were perfect for me, for my use. Very different from the pastels one can find in art shops. So yes, I mixed them with water too. I especially wanted to find a way to present them without the need for a frame and glass. But I never found a solution that would keep the beauty of pastels. They lose their luminosity and freshness over time. So I decided to use the pastels normally, just using only pastel. I never used my fingers or anything else to spread them on the paper. I’ve always been very strict on that aspect, no use of fingers for blending as the pastel must remain strong and pure.

As to whether the pastels were more salable or not? They were salable because I could probably make them sing, but they were also very difficult to send because of their weight.

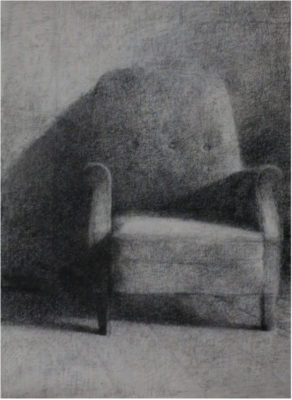

LG: What are some thoughts you have on why you choose what to paint? How important are the actual items you choose to be in a painting, like a chair, dish, or fruit?

Mathieu Weemaels: I never think: I m going to paint this because it’s the symbol of death, life, love–all these things. I always trust my instinct and the meaning comes later. Sometimes years later, I realize what I was thinking about. With time some objects came to have their own meaning. In my objects collection, I have, for example, a striped towel. A part of my family is Jewish. I’ve been reading a lot about the war and the holocaust, concentration camps and such. With time I felt, I understood that this striped towel had something to do with the suffering of Jews during the war, so with my roots. Also, the rose fabrics I was painting a few years ago. I suddenly realized I was also talking about my family. Their name is Rosenfeld which means a field of roses. But there again, the meaning came after.

LG: I read that you might use a mirror when setting up a scene to paint. Do you use a mirror to find new compositional possibilities, or are there other concerns as well?

Mathieu Weemaels: Using a mirror was a way for me to deconstruct reality, to make a kind of mix between abstract and figurative painting. My father, one day, gave me a big mirror, telling me I could use it for my drawings. And I found it very interesting. I loved the idea of a window to another world that would hopefully be better than this one. I often explained that: a world without Nazism, Shoah, racism, drugs, wars, etc.–a kind of ideal world. I realized that mirrors are vibrant from many points of view. The meaning as I said ( one could add ideas about life, death, visible and invisible world etc..). But also on a formal point of view as they bring a geometric aspect that I found interesting. So even if my drawings were figurative, they had an abstract and 2D aspect. I never wanted to try to copy reality.

Finally, mirrors are also an interesting way to do something cubists did–painting the visible parts of objects and the back, which isn’t visible. Mirrors allow me to show all the parts. I’ve often played “games” with reflections, as I never wanted to paint things exactly. The object’s reflections were sometimes a bit different from their origin. I liked that. And I still do that nowadays. It brings a dimension of time in the painting.

LG: You seem to put a lot of effort into selling your work online through a number of online art marketplaces. Has this been successful for you? What can you say about your experience with selling online that might be helpful to share?

Mathieu Weemaels: No, it has never been very important for me. It never worked very well. The most important sales were in private exhibitions—also, the most critical moments. Showing and selling online is a bonus, a way to open the door to the world. Also, away, and that’s a crucial point, to be not too dependent on a gallery that could take advantage of this situation and ask the artist to paint what sells, like in the music world. Before, if a musician was not in the grace of a distribution label, he was nothing. Now an artist can create his own audience. There are negative and positive points with this situation. As I do here, answering these questions arriving from the USA. I love that way to share all around the world. I find it fantastic.

LG: You also show your work with a number of galleries in Belgium, France, Denmark, and Italy. Do these galleries ever express concern about your selling of work in online markets?

Mathieu Weemaels: Yes, from time to time, I had discussions with gallerists, but not that much. They know that reality. But online will never show the real aspect of a painting. So I think they have a great advantage. And if someone arrives in an exhibition and falls in love with a painting, he’ll probably want to buy that painting and no other one. So both. Galleries and online seem to be working quite well, not sure one destroys the other. Time will say. But for now, that’s how it is. If I had a gallery selling my paintings for high prices, allowing me to “earn my dog’s life” as Degas said, and if that gallery told me: please don’t show your work on the web, I would have said ok. But it’s not the case, so the web is an opportunity to see, show, and sometimes sell. And the galleries can say what they want, I’m the boss 🙂

LG: Has the Covid pandemic affected you much in Belgium? Has it had much of an impact on your work?

Mathieu Weemaels: I often thought during that period that nothing changed for painters as we were always alone, in our studio, far from the noise of the world. So in the first weeks, it has been a fantastic period for me, and I also think for other painters. It became complicated with time when I discovered the troubles due to the covid and still more due to closing the economy, schools etc.

Then in May 2020, something terrible happened during the pandemic: my brother committed suicide. He was not feeling well, but I think the situation had something to do with his act. He needed the noise of the world and couldn’t stand its silence, empty streets, closed bars. After that, I spent one year thinking about him and his terrible act almost every day. I made several paintings for him. They were kind of messages I was sending him. So yes, it affected me.

I also noticed that during exhibitions, when they could happen from time to time, visitors were delighted and attentive, more so than usual, as if art was a vital purpose necessary to thrive. That’s how I felt it.

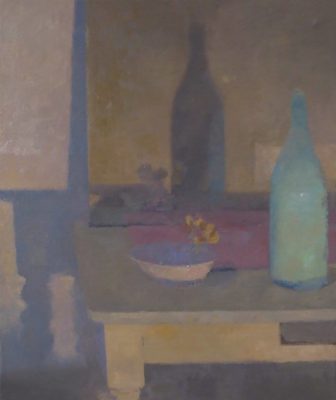

Blue Requiem, 2021

Noir & Rose, oil, 2016

Thank you Larry and Mathieu for this very lively question/ answer exchange which gives all of us insights into the creative world of this very interesting and poetic artist.

Merci Matthieu pour ce partage généreux..

Tu nous apprends des choses sur toi, ton travail, tes inspirations, ta famille,….

Cela me touche et sans doute que la prochaine fois que je verrais ton travail, que j’apprécie, je le verrai avec un autre regard

et une autre approche.

Bonne continuation cher voisin,

Amicalement

Brigitte