Review by John Goodrich, guest contributor

Anna Zorina Gallery

until October 15, 2022.

Certain traits – a mischievous spirit, a shrewd take on history, a love of the sheer materiality of paint – will always stand an artist in good stead. John Bradford possesses all of these, plus others that are arguably far more important: he is also a keen colorist, and an eloquent orchestrator of forms – this eloquence vying, startlingly, with the coarseness of his technique and goofiness of his imagery.

At a glance, Bradford’s paintings at Anna Zorina confirm an artist full of passionate, if peculiar, purpose. While his images speak of the civilized and traditional – painters at work, often in nineteenth-century smocks and skirts, grand galleries of paintings, hung salon-style – all are rendered in slashing, swirling strokes of color that run the gamut from exuberant out-of-the-tube pigments to tawny browns and turgid grays. The scenes are generalized, as is experienced through the lens of a dream, and his figures’ gestures often graceless, at least in any conventional sense; a stretching arm may consist of a single slab of pigment. A certain loopiness presides over the show; before our eyes, the merely picturesque acquires a solemn radiance through the most wayward of means.

And radiant these paintings are, thanks to Bradford’s luminous color. In real life, light has of course no weight. But the light generated by artists’ colors can lend emphatic pictorial weight to objects. It can impart volume, mass, location—a presence. Coordinated across a canvas’ dimensions, the weightings of forms can build towards a climactic whole. Bradford employs color – in both local volumes and broader orchestrations – to lend an offbeat authority to his scenes.

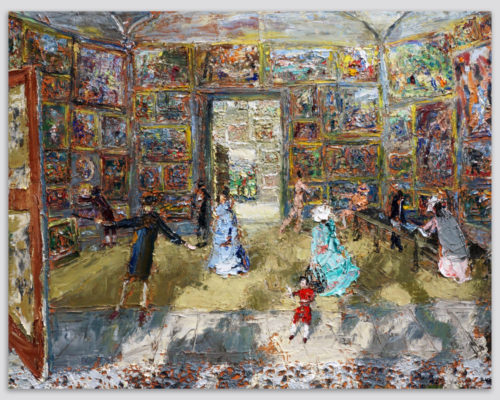

JOHN BRADFORD In Praise of Selling Art, 2021 acrylic, oil on canvas, 60 x 78 in. Images courtesy of the Anna Zorina Gallery

In his “In Praise of Selling Art” (2021), for instance, a patch of retiring greenish-ochre becomes, palpably, the shadow of a woman standing on the sturdy yellow glow of the floor. Together these colors anchor the rising column of brilliant blue tints and deep, near-black ultramarine – the lit and shadowed portions of her dress. The quantification of light has begun, and Bradford pursues it through an entire scenario that embraces nine other figures, all in a specific light of a large gallery space. A child in a bright red coat reads theatrically from a sheet of paper, a woman in a gray jacket leans over a table; despite their abbreviated modeling, every gesture rings true. The light shapes the physical spaces, too; at the center, a doorway leads to a more brightly illuminated room beyond, and a distant doorway in this gallery leads to the most vivaciously colored space of all, the outdoors.

JOHN BRADFORD Berthe Morisot in Her Studio, 2021 acrylic, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 in. Images courtesy of the Anna Zorina Gallery

In “Berthe Morisot in Her Studio” (2021), the colors of the floor shift improbably from gray-blue to warm pink to green, but somehow capture a perfect impression of sunlight sifting through a window and flowing across the room. A magenta-toned wall behind completes the effect of a bright, contained space, punctuated by the precise notes of painter and model.

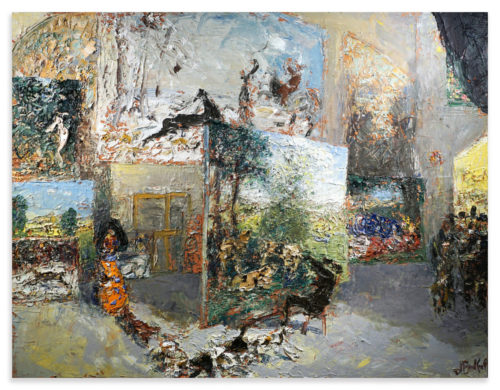

JOHN BRADFORD The Studio, 2022 acrylic, oil on canvas 60 x 78 in. Images courtesy of the Anna Zorina Gallery

Countless strokes of color forge a unified impression, once more, in the six-and-a-half-foot-wide painting “The Studio” (2022). Here, a vast interior space moves though a complex sequence of lit and shadowed zones, while a large artist’s canvas, angling through the depicted space, holds resolutely at the center, its hues balanced point-by-point against the background’s.

Allusions to the masters abound. In the aforementioned “Selling Art,” a painter eyes us while standing, à la Velasquez, next to his huge canvas. ”The Studio” clearly references Courbet’s “Allegory” in its basic composition, while introducing an element borrowed from another Courbet painting: a stream of hounds, frolicking across the studio’s foreground like a piece of knotted fabric. (One of Courbet’s hunting scenes – with dogs – has been added helpfully to the back wall.) Several of Bradford’s canvases depict paintings with Renoir-esque nudes, whose forms extend with fleshy vigor across the surface.

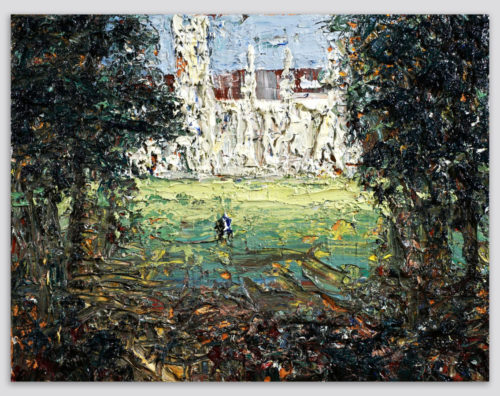

JOHN BRADFORD A Constable, 2021-2022 acrylic, oil on canvas 14 x 18 in Images courtesy of the Anna Zorina Gallery

Indeed, suffusing the entire installation is the aura of master-painting – of an artistic genius’ working process, and the ceremonious displayed of the results. In this sense, Bradford’s paintings are deliberately, conspicuously art about art. But they achieve this in the best possible way, by reasserting the supremacy of light and color. His paintings are not illustrational riffs on cultural icons; the artist imparts to his recycled subjects a new, peculiar gravitas, arrived at through original means, and based in expressions unique to painting. In at least one case, Bradford even exceeds his source material; I found his version of Salisbury Cathedral (dare I say it?) more incandescent and decisive than the Constable paintings that inspired it.

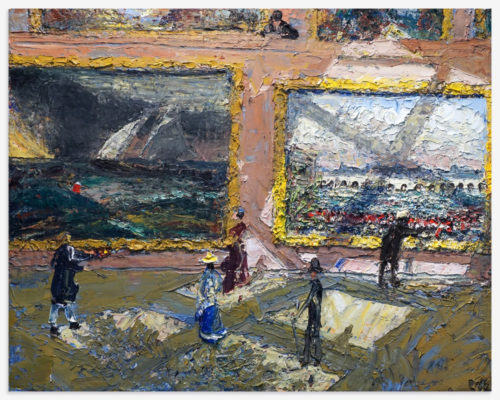

JOHN BRADFORD Renoirs in the Studio, 2022 acrylic, oil on canvas 36 x 48 in Images courtesy of the Anna Zorina Gallery

At times the light’s shaping of spaces takes on a surreal intensity. Somehow, Bradford finesses the telescoping luminosities contained in a painting like his “Renoirs in the Studio,” (2022), in which he captures Renoir’s radiance of modelling within his own radiant depiction of a gallery wall, neither one of them diminishing the other. Qualities of light take on a complex urgency in a painting like “Varnishing Day – The Red Buoy” (2021), in which the massive girders of an unseen skylight cast shadows across paintings and walls alike. Stranger still are views of galleries in which the shadows appear to be cast by irregular tree canopies or even tiny clouds – circumstances so unlikely (and so unconducive to normal art-viewing habits) that they test our notions of the credible.

JOHN BRADFORD Varnishing Day – The Red Buoy, 2021 acrylic, oil on canvas 48 x 60 in images courtesy of the Anna Zorina Gallery

But then, it’s the eloquence of an artist’s vision, not the logical reconstruction of the physical world, that makes for meaningful art. On this score Bradford’s paintings reward, in ample, offbeat measure.

Anna Zorina Gallery

September 6–October 15, 2022

532 W 24th St, New York, New York 10011,

212.243.2100

Leave a Reply