Visible Influence: Janet Niewald and Wilbur Niewald on Influence, Teaching and Practice

Interview by Jessie Fisher, guest contributor

Our invisible teachers, those we visit in the museums and galleries, expose us to the breadth and the possibilities of our craft, while our visible teachers, our peers, partners, colleagues and students, and for some, our parents and children, provide invaluable insight into its practice. Before the painter Janet Niewald could talk, her mother exposed her to Bach’s 2-Part Inventions. These contrapuntal auditory structures fused with her early visual experiences of the abstractions painted by her father, Wilbur Niewald, which were hung throughout their home. These pre-verbal rhythms have provided the structural groundwork for Janet’s complex visual and narrative structures to inhabit. These same images also provided the point of departure from which Wilbur’s practice evolved from an indirect engagement with a subject born of the studio, into an unwavering devotion to the abundance of appearances a directly observed motif offers.

I have long been an admirer of Wilbur’s work and had the pleasure of knowing him for the past 16 years, visiting him in his Kansas City studio and attending his exhibitions and gallery talks with students in tow. Just after meeting Wilbur, he suggested I look at Janet’s website and I was more than a little impressed by the articulate and varied body of work of this decorated professor and accomplished painter whom I have since wanted to reach out to. I had the pleasure of meeting Janet this past August at the dedication of the Wilbur Niewald Senior Studios at the KCAI Painting Department. She was able to arrange for the three of us to sit down together at Wilbur’s home in Kansas City on a lovely August morning, with the 7-year cicadas in full chorus, to discuss influence, teaching, and practice. The following is a collection of excerpts from our conversation in 4 parts, beginning with written correspondence with Janet.

I would like to thank Janet for her diligence and excellent writing, Wilbur and Gerry for inviting me into their home and Wilbur for his continued insight and encouragement. Images of Wilbur Niewald’s work are generously provided by HAW Contemporary and E.G. Schempf.

Jessie Fisher

Professor in Painting at the Kansas City Art Institute

Janet Niewald exhibits her oil paintings, watercolors and drawings nationally and regionally. She was selected for two Invitational Exhibits for non-members at the National Academy of Design Museum, NYC. Her work has been included in many respected juried competitions, including the Bowery Gallery, the Prince Street Gallery, and the First Street Gallery biennial competitions, all in NYC. She shows often at university venues, such as at Wright State University’s “Drawing from Perception”; a 3-person show, “Pictorial Strategies inches, at William and Mary; and a solo show at Washington and Lee University. Her work has been exhibited at art centers in the Northeast and the South (SECCA; the Greenhill Center; the Sawtooth Center; the Washington Depot Art Center, CT). Her paintings have been shown at the Masur Museum in Louisiana, the Taubman Museum in Virginia, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. She was affiliated with Bedyk Gallery, Kansas City; Munson Gallery, Santa Fe; and Reynolds Gallery, Richmond, VA. After attending Connecticut College, New London, and the New York Studio School Program in Paris, Niewald transferred to the Kansas City Art Institute to earn her BFA in Painting/Printmaking. Subsequently, she received her MFA in Painting from Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. She was then awarded a year-long, Ford Foundation Grant with a residency at the University of Georgia, Athens. Following a stint of teaching at UGA, Niewald moved to Blacksburg, Virginia where she still resides. From 1980 to 2014, she taught in the School of Visual Art at Virginia Tech where she was awarded the SOVA Teaching Excellence Award as well as several individual research and teaching grants. In 2008, she received the Virginia Tech College of Architecture and Urban Studies’ “Career Achievement Award”

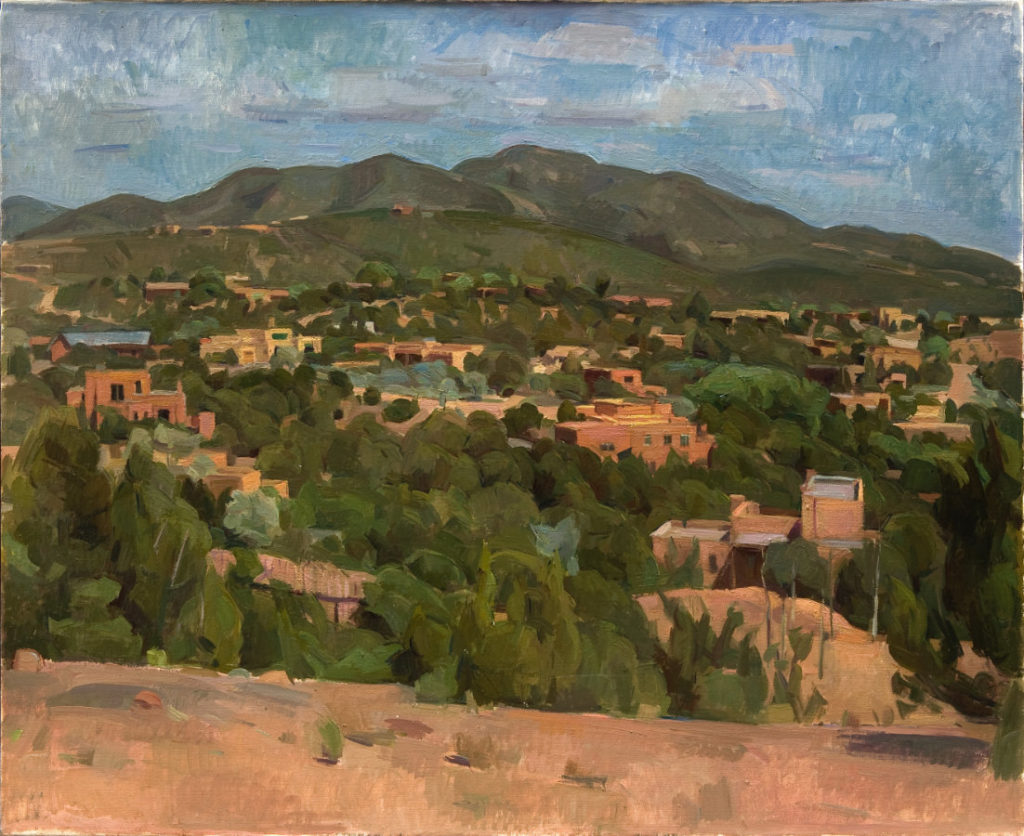

Wilbur Niewald is professor emeritus of painting at the Kansas City Art Institute, where he studied, taught, and for twenty-eight years, served as chair of the painting and printmaking department. Under his chairmanship the school was known as one of the best traditionally based undergraduate art school programs in the US. He has influenced generations of students during his long tenure in the college’s heralded painting department. Prof. Niewald also taught in summer programs at the NY Studio School, Yale University, Boston University, Vermont Studio Center, and Chautauqua Institute. He is the recipient of a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Charlotte Street Fund, based in Kansas City, Artist in Residence, Grand Canyon National Park, and the Distinguished Teaching of Art Award from the College Art Association. He is a member of the National Academy of Design. Prof. Niewald’s recent exhibitions include a retrospective at the Albrecht Kemper Museum of Art; Marianna Kistler Beach Museum, Rider University; Dolphin Gallery and Morgan Gallery, Kansas City, MO; Wright State University, OH; a retrospective at the Kansas City Art Institute; New York Studio School; Dorry Gates Gallery, MO; Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art; Zeuxis Gallery, NY; National Academy Museum; and the Ingber Gallery, NY. Niewald’s work is in the collection of numerous museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art and the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art

PART 1

Janet Niewald- ON INFLUENCE, NARRATIVE AND TEACHING

It’s funny, as artists, we often don’t know which comes first – something we see that influences us, or something we imagine or feel that is then confirmed by something we see. As an artist’s child, I saw a lot of art, historic and contemporary, though deeper knowledge and awareness began to come much later.

In museums, my parents sometimes went separate ways, my father stopping to draw and my mother exploring other parts of the museums’ collections, with me in tow. I developed, and retain, a voracious, “wide eye” – Sung-dynasty landscape paintings, Japanese byōbu, Northern European altarpieces, Giotto, Masaccio, Titian, Mayan frescos and cylinder pots, 20 th c. Mexican muralists, Monet, Van Gogh, Matisse, Mondrian, Pollock. As someone married to a ceramicist, I study more pots than most painters do, particularly Ancestral Puebloan and Mimbres ceramics. Rembrandt and Giacometti have been especially moving to me, in all media and through all periods of their lives, as well as mine. Both artists explored and revealed, as Mary Shelley wrote in Frankenstein, “the tremendous secrets of the human frame.”

As I age, my interests change. For example, when young, I was interested in Archaic and Classical Greek sculpture but now, Etruscan. Cezanne’s influence may feel somewhat inevitable to me, both directly and indirectly, but with both Cezanne and Alice Neel, I continue to feel something akin to what I feel with Etruscan art–a frank joy in nature rather than reverence for an idea.

During the COVID year, unable to travel to museums and galleries, I was surprised just how little I looked at my artbooks. More and more, my influences come from nature – the mountains, the trees, the river running through our valley, natural processes and events, and the other animals I see, everyday. Perhaps now, I might “see a landscape instead of a Pissarro”, to paraphrase Giacometti (also an artist’s child). What I observe and experience in this world, what I live – and also, what I read about natural processes and about the crisis in our relationship with the rest of nature – are most vital to me.

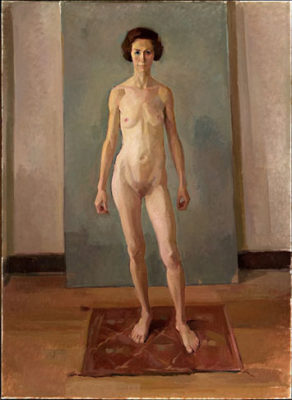

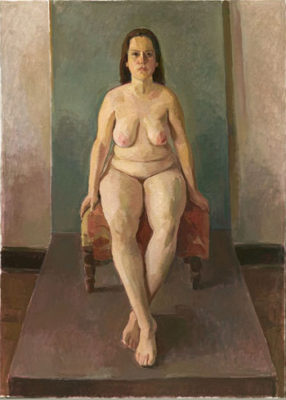

I don’t consider myself a true narrative painter – I’m more of a quasi-narrative artist, I think. To discuss anything at all about my subject matter gets right to the heart of my work and I find it difficult to talk about. A tendency toward narrative surfaced quite naturally in my work, especially during the past decade. Story-telling, or story interpretation, has a deep history in painting, perhaps from its inception since we don’t really understand early cave paintings or rock art. I’m not inclined towards doing “history painting” and I generally work from observation, but I read a lot and sometimes books affect my choices in the studio – I don’t have a big nose but I follow it.

I often read nature/scientist writers, (Suzanne Simard, Sylvia Earle, Barry Lopez, and others), and they have had an impact on me; a current series of self-portraits relates to my own environmental concerns and consequent reading. That said, my sources can be more off-beat – like a late-night murder mystery called “The Thing about Thugs“, by Tabish Khair. In it, I learned about the shadowy, possibly mythical, “Thugs“, gangs of highway bandits and murderers in 19thc. India, who used yellow ropes to strangle their victims. I had just started a painting of a seated nude – the next session, I handed the model a length of yellow rope to stretch across her thighs. One thing led to another and a triptych developed, three different women with ropes. The triptych may refer to various mythological trios of women, or not. I came to know all the models for this painting; one was a very good friend. They are “ordinary” people and, as such, have the potential for terribleness. For me, narrative is often just another way of expressing the complexity I find in the ordinary.

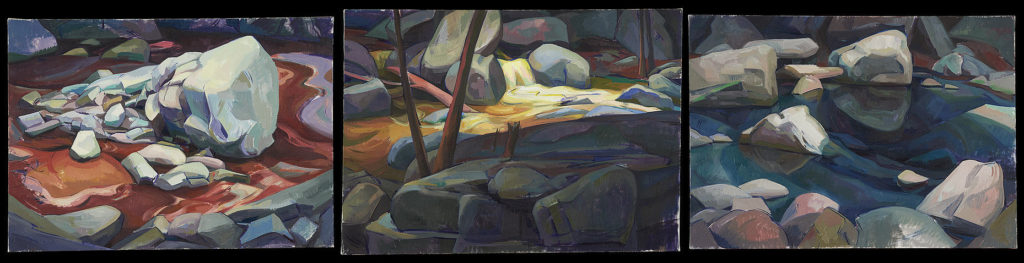

My still lifes often come from a tendency to pick up cool things as I walk around our land – bones, antlers, teeth, cedar roots, bird nests made of our horses’ hair, etc. My husband also brings me his finds; I have a good recipe for bleach baths for some of the juicier finds. And I have a postcard collection of paintings, and of photos of animals. Also, I like textiles and rugs. I’m not an object-shopper, but I can be moved by an object that I encounter – an antique, Korean ceramic bottle; plastic taxidermy mounts; a Zapotec rug; a shower curtain of a breaking wave; fossil ammonites.(The ammonites took on an added significance after I read Elizabeth Kolberts’ “Sixth Extinction”.) Some paintings and many drawings stem from studio clutter, or detritus; some are more consciously arranged. The relationships between juxtaposed objects, and our strange personal relationships to all kinds of objects and images, fascinate me.

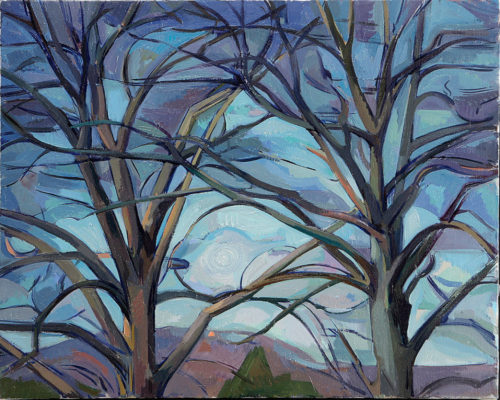

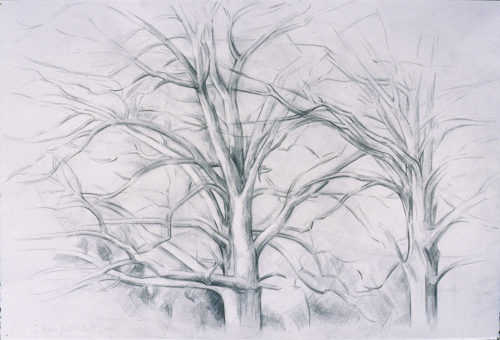

I can’t say enough about the land and my relationship to it. Much of who I am and what I do in the studio comes from the rich, dynamic land where I live. I don’t view “it” as “mine” but rather a briefly borrowed gift in which I am immersed. The mountains and the trees, like the two oaks behind my studio, are daily companions and mentors, not just paintable subjects. One mountain, called Paris, appears different, almost every morning. The biggest lessons for me have had to do with flux – a big oak killed by Hurricane Andrew, a large cedar split by the wind, gardens eaten by hungry deer, the changeability of brush piles, animals that come and go, our variable weather. Lots of going, but then coming too.I don’t doubt that the dynamism of nature has formed me as an artist. How could it not?

I don’t think all artists need to teach. Throughout history, some artists have taught, some not, and I don’t think an artist has to be “trained”.Art education is big business now, as is the world of art sales – and none of it is necessary to the deep reality of art. Art, the need of it, precedes it all.

For 34 years, I taught at a large state university that emphasizes engineering, technology, and research sciences.I taught numerous non-art majors, many from the life sciences – they were often thoughtful and eager students (and my interactions with them informed my interest in environmental issues). The institutional ignorance about art, which faded over time, lay primarily with the faculty and administration, not with the students. In early years, I taught both studio and lecture courses but during the final decade of my teaching career, I was able to focus on teaching painting to art majors, with full control of the studio situation; I was able to relax!

Sometimes, we get more from struggling than we do from having everything set perfectly for us. Through teaching, I actually learned how not to explain everything; how to manage my time (as an exhibiting artist and a teacher, with family and home responsibilities); how to lecture to 200 people without vomiting in advance; how to write clearly and be a better reader; how to make do with what I had and how to advocate for myself and others to make things better. I don’t really know how teaching directly affected my painting practice. I did often enjoy talking with upper-level students, seeing what they were interested in, encouraging them to pursue those things, finding ways to help them do that. I’m sure that they introduced me to things I would not have seen otherwise. But I also liked teaching drawing and helping students (and myself!) to see. Despite the many different courses that I taught over the years (22 courses, in fact), my teaching and my studio experiences were generally complementary somehow. I made it that way. Until finally, I had enough, and retired.

PART 2

Wilbur and Janet Niewald – ON TEACHING AND SEEING

“I want to emphasize the importance of drawing. When I paint, I am drawing.

I am not only drawing when I paint, but when I see.

I am constantly putting things together two-dimensionally; I am drawing all the time…”

-Wilbur Niewald, Oct 14th, 2021

Wilbur Niewald: Actually, it’s drawing itself that I could talk about. At one time we (at the Kansas City Art Institute) had a president who wanted to really define drawing. So, we (the faculty) met and asked, ‘What is drawing?’ We had a long discussion, and, in the end, it was ‘marks… in relation’, but I’d even take it a step further. I can say drawing, in addition to design, is anything where you’re setting up a two-dimensional relationship. In other words, I can take blocks of paper and train the eye to set up the relationships, even to something that I see, and that would be drawing in the larger sense, to me.

One of the faculty members said that we needed to draw from the cast. Well, I was the younger teacher, so of course, I was asked to teach the drawing from the cast. We borrowed a few Donatello casts from the Nelson-Atkins Museum, and so, I was going to teach it. Well, I knew my influence to drawing right then was very much my teacher, Campanella (Vincent), and my ideas, (were) drawing primarily using charcoal with short poses. But that then puts the big question, would I have been, in another situation, required to change my thoughts about drawing at that time, or train myself to teach, a longer sustained pose, which would have been foreign to me. And that’s when I found, for me, teaching had to be satisfying to the teacher, otherwise you’re not teaching honestly. So, what I did, I got the Donatello and other sculptures, and put it in the center of the room we were around (it) in a circle, and they would draw for one sitting, and then I would turn the sculpture a quarter, and then we would draw again. And that’s the way that I was able to do the fast drawing which was satisfying to me. Now, later, later even in my teaching, I would’ve done it a little differently, in that I would’ve had a more sustained drawing and we would probably not even be working in charcoal.

Janet Niewald: But the drawing doesn’t even have to be in relation to what somebody sees. I was thinking about Matisse… the cut paper, that in a way that’s a form of drawing, with color of course. All drawing, and you and I agree on that, is color. The cut paper as you’re arranging it, moving it, that’s a way of drawing. Matisse is not using it observationally in response to (looking at) something,

Wilbur Niewald: No, but he is in his mind…see it’s almost like it’s a form of thinking, drawing is really visual thinking, but it’s like you said, design, isn’t that the French word for drawing, dessin?

Janet Niewald: Yeah, because it’s so, so fundamental. You know when you look at that cave paintings, Altamira, Lascaux, which I know you like too, that you know that it’s just such an instinct, a drive, a human drive… it’s interesting.

Janet Niewald: You know I had a similar thing. I taught at a very different institution, as you know. Our question about drawing proposed by our Dean, in all seriousness, was if you can teach 20 students drawing, why can’t you teach 200 students drawing at one time. It was when they insisted that I teach anatomy, and I said, well I think anatomy is very interesting, but it’s not what I do. They were all surprised. They assumed actually that because you paint the figure and you come from certain kind of background that your background included anatomy. I often would have a big class of 30 students, and I would get 3 skeletons and group them in 3 circles and say let’s draw the skeleton today. You do end up talking about the bones, but not with their formal names that a doctor needs to know. It was actually my only way, as you say, to make it integrated to who I am.

Wilbur Niewald: Yes, exactly.

Janet Niewald: Other faculty, many of them abstract painters, went and got books on anatomy and learned all the bones and the muscles, one of them learned the nerves. This is not going to teach you how to see, not going to teach you how to draw.

Wilbur Niewald: In my experience of setting up any kind of program which meets the needs of all students, for example, with drawing as a subject, we always ended up feeling that it was the individual description of what they (the faculty) would do, because anatomy, to me, is not a requirement. But, if you’re like Bill McKim, I said sure, go ahead and teach with anatomy as part of it, that’s fine. Its (teaching) defined always by where you are as an artist. This has stayed with me. When I was retiring, for some reason this came out. I was sitting with the faculty, my own faculty in painting, and I said, I would never want to be in a position to set up a program, as a provost, I just want to be myself teaching, and let’s say one is in a position to say what is basic for everyone. Do you think that everyone should have an experience in drawing where they were correcting to what they see? And interestingly enough, particularly, one faculty, said no. And I couldn’t argue against it.

My thought is, suppose you took the first day of a drawing class, let’s say you draw from the model, what are they trying to do? Basically, they’re trying to draw what’s there, in other words, to correct what’s there, and even if it is controversial to some, teaching for me was always an extension of a personal experience in the studio rather than a philosophy of teaching itself. I didn’t teach the medias of drawing, but I taught the students, first with charcoal and then with pencils, erasers and good paper, to develop the ability to see more clearly. I wasn’t teaching the students to make art, but to see. You see drawing is the small part between the media and the idea, and in my classes when I would learn something about this, I would share it with the students.

Janet Niewald: The idea of correcting is a difficult thing especially for beginning students. I encountered a lot of them (students) where I taught, they didn’t like to make changes to work, which meant if you if you can’t make revisions and changes to your work, the work is controlling you. If you’re not in control you’re not going be able to think through something. So, it’s like you’re stuck with whatever you do at the beginning, ‘I don’t want to change it’, ‘that’s perfect…’, and so drawing from a model or observation of any kind where you do make corrections, is a natural way for students to learn how to think about the process of making something, and that it’s not a bad thing, to make changes and revisions, it’s a good thing, based on the drawing, and it’s a very natural way to get to that. What was it Matisse said in Notes of a Painter, something like, ‘Accuracy was (is) not Truth’ (Exactitude is not Truth, Precision is not Reality) I may have that wrong, don’t quote me!

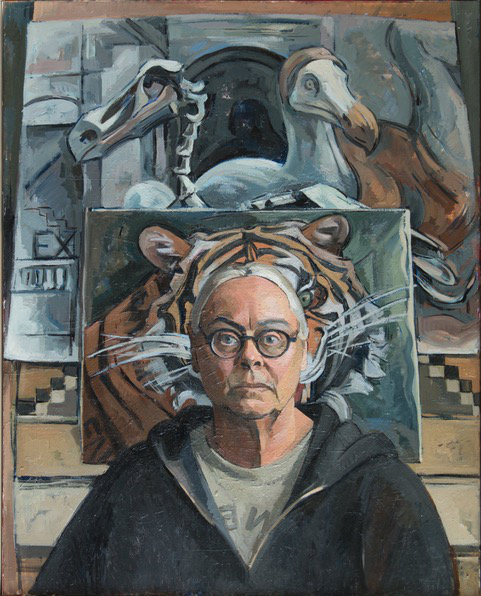

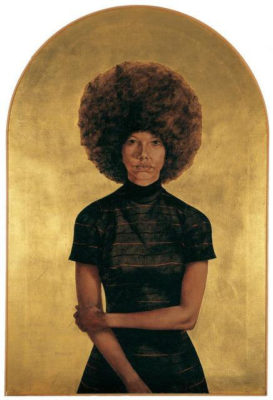

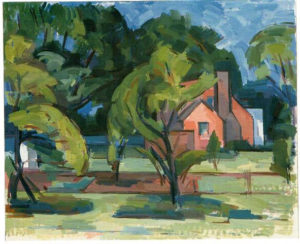

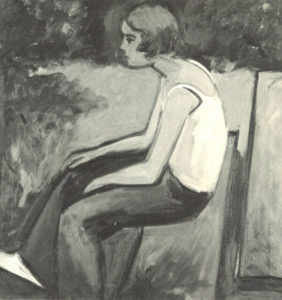

Janet Niewald, The Actor (Harvey), oil on canvas, 38×32 inches, 1997

Wilbur Niewald: Yeah, I can take that. One of my faculty that I had some differences with because I did emphasize the idea of correction, had posted…’Matisse: Accuracy is not Truth’, as if I were to carry on with this, I had to know that. At that time, I was studying Matisse because I was giving a thing (lecture, workshop), which I don’t do very often, at Smith College and I was using Matisse, who also said something like, ‘…if I get closer to what I am after, then that’s right for me…’, in other words, there’s always something in Matisse’s drawings, in contrast, to say Picassos’, which I really discovered at St. Paul de Vence, at the Matisse Chapel Chapelle du Rosaire), that they (Matisse’s drawings) are very naturalistic in a way. They are not stylized, they are more out of nature, out of observation and therefore more expressive.

Janet Niewald: Never repetitive. In the de Vence chapel, it’s interesting how individual they were (are) Now, the other thing Matisse said is about format in drawing. He said, ‘If I…’ again this is misquoted I’m sure, ‘If I look at something and I draw it on a vertical page, I won’t draw it the same if my format…’ and again that’s not the word he used, ‘…my format is horizontal, or if it is smaller or bigger, I will see it and draw it differently.’ And I’ve always found that really profound, there’s not some kind of overriding rule when you look at something about how big or small or where it should be placed on the page or on the canvas. That it all has to do with the response to that moment that thing, and that includes what you’ve picked up to draw on. I’ve always found that really profound.

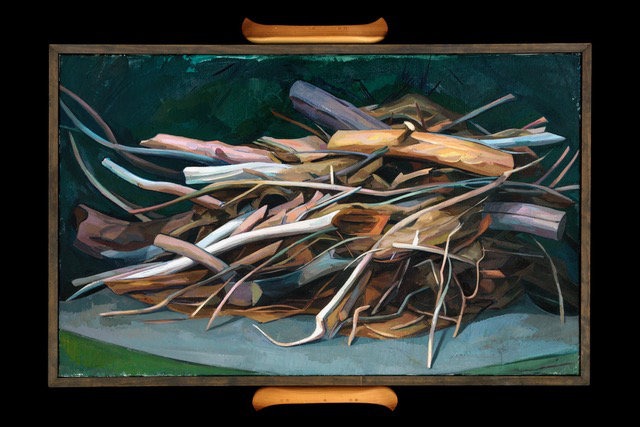

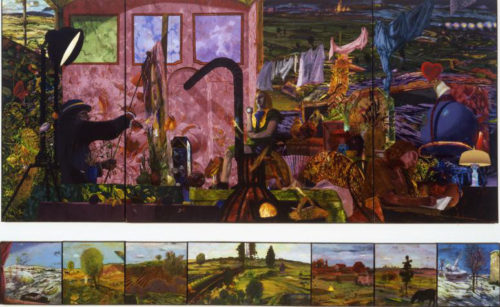

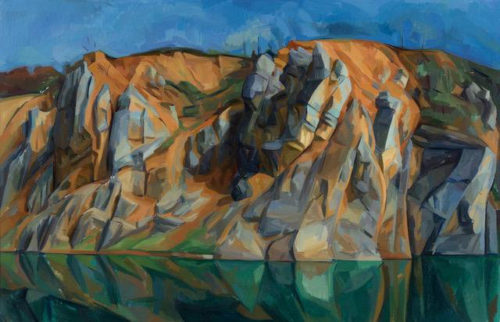

Janet Niewald, Brushpile 1, oil on canvas, 26×42 inches, 2007

Wilbur Niewald: Yeah, I think so too. And you know, one can make the subject smaller, in other words, do it to the format. I’ve never entirely understood this, it’s quite natural to draw to the format, in other words, you reduce it.

Janet Niewald: Like those tiny Rembrandt self-portrait that are like postage stamps?

Wilbur Niewald: Yeah, it would be perfectly natural, (to reduce) but I don’t think you could go over life-size without it becoming more an idea. But you see, I think that’s learning. In other words, I have the same experience with my still lives, early on they were bigger. I think it’s almost universal, I mean that most students tend to do that, and then you learn… so why is it important to learn to bring it to, I don’t like to use the words site/size, but to the size that you see? All I can say is that if you’re in accord with the subject, you’re in accord, and that does take time.

PART 3

Wilbur and Janet Niewald- ON INFLUENCE

Janet Niewald: Obviously you (Wilbur) are an influence on me, but then beyond that, there’s been a lot of different kinds of people that I have both worked with, and two other painters who I worked with who were very influential. Barkley Hendricks, who was actually my first painting teacher at Connecticut. (W: Yeah) Remember, you met him, and he had just come out of Yale, he was just starting to teach at the school where I was for the first couple of years, Connecticut College, and he was a huge influence. And I have to say that I, I hadn’t gone to school planning to be an artist at all. I was headed a very different route and I just kept finding myself in the painting and drawing studios. I was a nuisance, I would go and set up my French easel and paint a little corner. The faculty figured out somebody was coming in, and setting up their easel, and they didn’t know who I was. I was not enrolled in class. So, I would get these little notes like, ‘Who are you? Go away!’. And finally, I started to enroll in classes and Barkley Hendricks was the one who really encouraged me to keep painting. I think I was intimidated, if I look back, at the idea of being a painter when it was so clearly what I needed to do. And, you’re kind of torn, and he said basically, ‘Screw that…’, you know, ‘…just do it’. And then Jim McGarrell was an influence, in another way, about narrative.

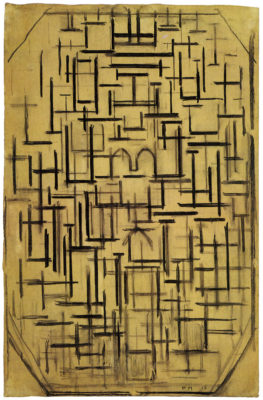

Wilbur Niewald: Influences, well, I suppose it’s true, that the first one, and still the underlying one, is Cezanne. And I remember, even, having a book of Erle Loran on Cezanne’s composition, and I didn’t agree with all of it, but it made me conscious of more than just being there and doing it, it made me conscious of form, of the formal relationships… so that became a distinct influence. And then the second influence should be…. it’s hard to explain. It was when they had an exhibition, at the school (KCAI) of works from the Museum of Modern Art, they were rebuilding or doing something to the museum, and they had the works up…. they had Burchfield…. and I can’t explain, when I saw the Mondrian facade, the drawing, it was had an incredible effect, everything else didn’t seem real, but that seemed real to me.

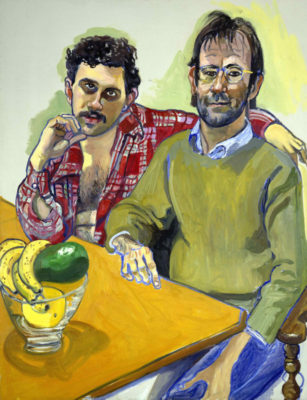

Wilbur Niewald: So, that was a tremendous influence, to me, not an influence… as it’s written, more the idea of… the vertical, the straight line, the vertical, the horizontal… of opposition. I also wanted in a way to be abstract. But what I found is that I could never be abstract because I could never put away the illusion of space. In fact, the illusion of space, in spite of it being an abstract idea, the illusion of space was really what I was about. I was really about color as an illusion of space, in contrast to Mondrian. Then as far as the influences beyond that…. all great art I suppose. My teacher Campanella (Vincent) influenced me to really look at painting… there were some particular artists, Giotto would be one, or, well, like Masaccio who, in a way, I really understand more than I do Michelangelo. In other words, it’s when you’re learning not how to take the actual work as itself, but to be more mannered. That became the base, sort of, and Rembrandt always, is still a giant, but I can’t say that it’s a direct influence. And then, Janet and I were talking about Neel, Alice Neel, who is an important painter, but I can’t say I had any direct influence (from her).

Janet Niewald: Well, you two are more contemporaries, when for me she was a member of the older generation, and a woman, and there weren’t many examples of that when I was a student in the 1970s. So, I can see where she’s more like a colleague to you in painting.

Wilbur Niewald: Well yeah, see we knew her, and I visited her in New York in her home too, and I have a letter from her…I’ll get that out. She stayed with us here. But… she… so what is it? I saw an Alice Neel exhibition in New York with another adjacent gallery with a painter that I knew, and I thought, Alice Neel’s (show) looked like a museum. And I think it was, what is it…. I happen to think that drawing is the thing that comes to mind. Cezanne drew better than his contemporaries, better than Manet, Monet, Courbet… and Alice Neel, in spite of what Hilton Kramer, who I knew, and I respect, he said that she couldn’t draw, but there is evidence that she very much could. So, in the end, the influence is the work itself, is that it moves you… you can’t really explain it.

Janet Niewald: You and I were talking the other day about Rembrandt, and we were saying, you know, what a powerhouse Rembrandt remains for both of us. But you said that you didn’t feel like you could really learn from Rembrandt, you said, ‘What could I learn from Rembrandt?’, which I thought was interesting, as I used to feel this way, until 2012 when I was in Amsterdam. And, for the first time I did feel like I wasn’t just standing there, wowed and just moved, I was also able to kind of see… ‘well look what he did there, he put something in the dark while he has something in the light… these are both kinda focal points… how interesting… the way he narrated, which was, well let me put it this way, was part of his duty as a seventeenth-century painter, you know, to tell a story, and the way he did it, I began to actually really access it. I think it’s also because that’s more of an interest for me now, to be able to narrate.

Wilbur Niewald: Yeah, afterwards I thought a little bit about that, and I would stand on what I said. Because it’s true what you’re saying, that like, say the ‘Clothmakers’ (Syndics of the Draper’s Guild). You don’t realize how revolutionary it was, to put that in that context in contrast to what was the norm of a group (portrait).

Wilbur Niewald: Right, and even recently, I’ve always said, for me, drawing… we draw in color. In other words, I would talk about, say the corner of this room, or ceiling, where it comes together. Now, when one is reacting to that, and this has to do with visual sensitivity, he’s going to draw that so lightly. You don’t think that it is because that’s the way it is, it’s not a structure. In other words, it’s not imposing (ideas, presumptions) upon the vision. And then I saw a Rembrandt drawing, and I could see even more how much he drew in color, so beautifully.

Janet Niewald: And they’re such wonderful expressive lines, amazing. So, would you say Cezanne, and for you Mondrian, Rembrandt… Matisse, to some degree?

Wilbur Niewald: : Yes, Matisse…..and Chardin…

Janet Niewald: I hate to keep bringing up Matisse again, in Notes of a Painter, and I know Notes of a Painter is right over here, I should just get it out, but he spoke about being at a certain point later in life and then going back and looking at your early work, to see what it was that really generated the whole thing for you. What it was then that you felt so strongly about as a youth, and I think there’s truth to that because you can go back and learn in your own work, early work in particular, what set you off.

Jessie Fisher: Wilbur, the other night at the dedication ceremony you mentioned that you found the 4X4” glass slides of the drawings you submitted to KCAI when you were 10-years old? These drawings allowed you to attend Saturday drawing courses with Ms. Poke. And then years later you found them at the KCAI slide library when they were shifting to the smaller format. Do you still have those? (Wilbur: Yeah!) Do you recognize any way of composing or way of moving the mark that you see in your work now?

Janet Niewald: Does it look like yours?

Wilbur Niewald: Well, I’ll tell you a story about that. The faculty was out here, we would periodically have them out here for dinners, and I mentioned that story. And it was Stan (Stanley Lewis) said, “would you (go) get that” and he thought that it told something…he liked them, and I’ll show them to you. What they show is that, and that’s why she (Ms. Poke) was a great influence, they showed a simplicity. In other words, at 10-years old some young people can draw very naturalistic things. This (drawing) was simple, it was a person posing, a simple pose of a man, seated. In other words, I like the simplicity, and I liked the simplicity in that the palette where we just had the primary colors, which I still use to this day, and that was another one of the big influences of this experience (being in school with Ms. Poke). But more than anything else it was her enthusiasm. She loved color and she loved Impressionist painting…. in contrast to what was going on at that time in the art school, which was more connected to the Academy, and they weren’t into Impressionism, that enthusiasm really made an impression on me.

So, the influences, all the way around, our influences are really where we are at the time, ourselves (as artists). But in conclusion, of where I am now, I want to emphasize that the great influence on my painting is Paul Cezanne. Some artists do say that Cezanne is the greatest painter to have ever lived…but was he greater than Rembrandt? Rembrandt, for me… just everything about his work… is the most incomparable artist to all others, but as I said earlier, not a direct influence. Cezanne has always been and still is, a direct influence on my practice. Cezanne is always contemporary for me. From when I first recognized him and his ideas, Cezanne is without a doubt, for me, the great painter of our time. His inspiration is always there.

PART 4

Wilbur and Janet Niewald – ON DRAWING AND PRACTICE

Janet Niewald: We (Janet and Wilbur) do talk, and it’s probably too bad in a way, we don’t talk that much about art… a little, always a little, and then when we used to go to museums together, you know like the Nelson (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art). David (Crane) and I would be visiting and as a family the four of us always went to the Nelson together and we would talk about things, you know, and surprising things like in the Asian section we would discover things that we hadn’t seen, so I’m sure there’s been a mutual influence in some way, but it hasn’t been very… self-conscious, is that the right word, yeah, it hasn’t been very self-conscious.

Wilbur Niewald: Well, I’ll tell you how I knew that she was an artist. First of all, it was when we went to the Grand Canyon in 1974. I gave you an easel…

Janet Niewald: And you thought you were going to get it back! They gave me a French easel for Christmas, was it Christmas or my birthday that year? But you guys had bought it for me, it was a gift, and I’ve always teased you that you probably thought that about a year later you probably get it back.

Wilbur Niewald: No, but anyway I could see the talent. Then when… I was teaching in Paris, through the New York Studio School, that’s the first time we were working together, and we went south and stayed in Aix-en-Provence. We (Wilbur and Gerry) came back earlier than Janet did, she was a student at the time and independently she continued to work… and then I knew. And she sent a beautiful letter that said, ‘I have decided to be a painter and I want to go to the best art school and that’s the Kansas City Art Institute…”

Janet Niewald: I did! And it was a huge decision, as you can imagine.”

Wilbur Niewald: “….and I want to study with daddy.”

Janet Niewald: Yeah, “I want to study with daddy.” And I had looked around, it wasn’t out of the blue. Before I went to France because I was at school in the northeast, I had gone to RISD and checked it out, I had it gone to what was then PCA in Philadelphia, and I’d gone to New York. So, I had considered art schools in the northeast. And then I began to put it together when I realized it was really truly painting that I wanted, I just think this (KCAI) was a remarkable program, just a remarkable program. I mean he (Wilbur) was an amazing teacher, but there were other amazing teachers- it was a phenomenal group.

Wilbur Niewald: We did have that, in my opinion. At that one little time there were 6 painting faculty, and I think it was quite honestly the best undergraduate painting department in the country. And at the time I honestly told Janet, that it doesn’t matter a bit which way you go in your own work. Because after all, what I was teaching was not a way to paint. At that moment students learned that if they went to graduate school and went on and painted abstractly that would be fine with me, and that was the way that I encouraged her (Janet) to feel free. And it’s amazing that she did, in a way, go the way she did.

Janet Niewald: And yet we have differences, you know, I work differently, and our studio practice is more different now than it used to be, that is that you have, I guess still, a morning painting and an afternoon painting, is that right? And then I’ve got usually about 7 or 8 things going- I tend to have a lot of different things that I work on. I cannot have one painting in the morning one painting in the afternoon, I seem to need to have multiple paintings going, and I also have some paintings that I work on that aren’t from observation. Only one of them so far has even been exhibited, and then I took it down took it home, took the top and bottom panels off, it’s a polyptych- a triptych with the top and bottom like a predella, so it’s like a 5-panel polyptych and I was so discouraged with it after I showed that I took it home and ripped it all apart and I’m actually now working back into it, so if I ever finish it will be like a 5-year wonder.

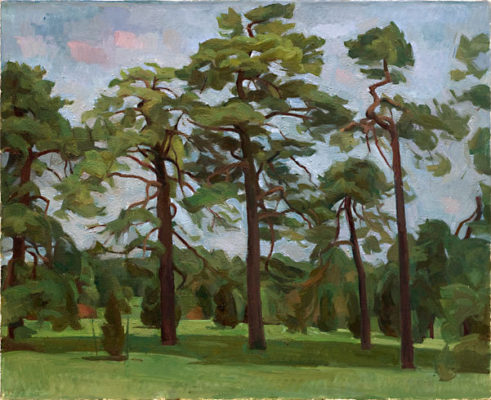

Wilbur Niewald: I am more morning and afternoon, and that is determined very simply by the sun, that is by working outside. In other words, the morning painting facing west, and then in the afternoon the sun is facing east….so that automatically I am working on two, but I don’t particularly like that…I always like a third one in the studio that I can work on when it’s raining. So at least three.

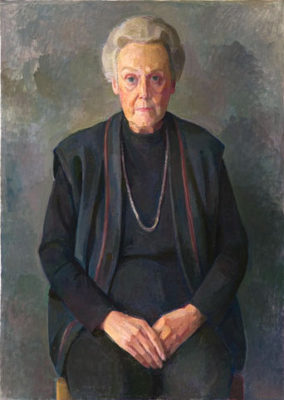

Janet Niewald: Well, you’ve had really four, because you have one here (at his home studio), and then down at the Livestock Exchange studio, plus two landscapes, the morning and the afternoon, in landscape weather, and then sometimes you have a self-portrait, or a portrait as well, so actually if you think about it, there are times you may have something like 5 balls in the air Wilbur!

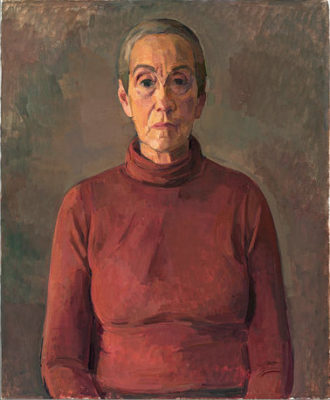

Wilbur Niewald: Yes, Pam (referring to a long-term portrait of his model Pam in his home studio) was always quite a major work that has been going on for years…

Janet Niewald: Is it done?

Wilbur Niewald: No! See, the truth is, she doesn’t know it (gesturing towards Janet), but I don’t need it, the model, contrary to what I preach all the time. There is a little thing right here (pointing to the outside corner of his upper lip) that I discovered can make a difference in the expression. This goes up just a little bit…. and I don’t have it. I fully intend to correct that. It’s amazing how moving it up a little bit can make the expression softer.

Janet Niewald: So, you don’t need Pam anymore?

Wilbur Niewald: No, not on that painting…

Janet Niewald: Did you know that David is posing for me now? This is an ongoing battle because mama doesn’t like to pose for daddy, and David doesn’t like to pose for me, so my mother and my husband share this aversion to sitting and being models.

Wilbur Niewald: I will say that Gerry, now really has cut it off. I wanted to do one more. I think it would be really great, but it doesn’t appear that it’s going to happen, I don’t think, but we’ll see. She and Pam were both outstanding models. I have always wanted to paint another portrait, and every three years or so, I have painted a nude.

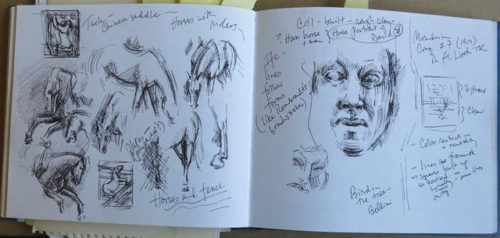

Janet Niewald: Getting back to drawing, I used to draw in my sketchbook every day, and then sometimes do bigger drawings, larger drawings, pencil or charcoal, and now I tend to work in a pen actually in a small sketchbook. Are you drawing as much as you used to?

Wilbur Niewald: Well, you know, I feel in a way that I have never drawn as much as I would like to, but, where drawing changed for me was, in the early years as a student and in early teaching, I liked to use charcoal, or chalk…conte crayon, that’s what I liked in terms of drawing, and then when we traveled, I always used pencil. And so, when I, after that first experience, coming back I completely changed, and this will illustrate how much I believe in that you’re teaching what you like, in other words, I completely put aside charcoal, and we (the students) worked almost exclusively in pencil. It just made more sense, and it was very simple, and it didn’t rub off, and even in a way it was like writing. But I have always wanted to draw more, in other words, it was hard to get that much in, but Janet, she draws a lot.

Janet Niewald: Not so much anymore, not like I used to, that’s why I was asking you because you used to draw a lot and you used to do a lot of watercolor.

Wilbur Niewald: Oh yeah, watercolor.

Janet Niewald: I think you did more than you realize. Consistently with your oil painting, you are also, often doing some watercolors, especially in the summer, or if we would travel, you know when I was young and living at home, we would travel, and you would work in watercolor wherever we went. And sometimes pull over the side of the road, get out and do some watercolors and mom and I would wander around looking at flowers.

Wilbur Niewald: It all had to do with where you were, in other words, I could never do this in watercolor now, (then) I could complete a watercolor in one session. I had watercolors that I sustained while we were traveling and could complete them in just one day.

Janet Niewald: (To Wilbur) When you started at the Art Institute (Kansas City Art Institute), not as a child, but for your bachelor’s degree, did you come in knowing watercolor? Had you painted in watercolor prior to that? Because, you started in illustration, actually.

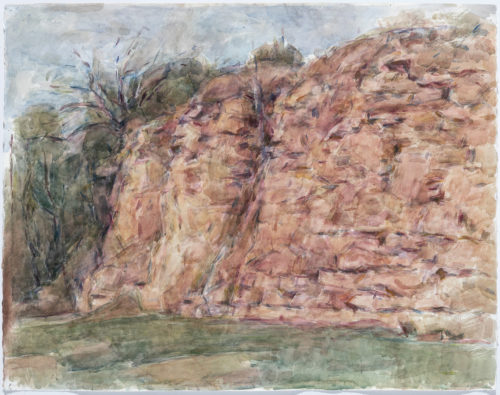

Wilbur Niewald: In high school, I did watercolor. Watercolor was always a very natural medium, I had to learn oil and other opaque mediums. But with watercolor, I liked the transparency. I never liked opaque watercolor, gouache, but transparency was always a very important part of my work. It’s really over many years and many watercolors I was really thinking of the abstraction of the…. (landscape). My watercolors, now, I work on for a long time, and I accept that. I would like to be able to stop (sooner), but right now, I would be very self-conscious. Right now, I have to push it…I don’t care if it becomes opaque …it’s all about correction, that’s what I care about.

Janet Niewald: I really admire daddy’s work in watercolor. For me it was the opposite, you know oil was natural for me, and watercolor was something I just kind of picked up on my own. At the Art Institute, nobody was really teaching watercolor, nobody was using it in the studios. I remember going to the campus art supply store, I saved my money and I bought up a watercolor brush and I got some little tubes of paint and I had plates that I brought from home. And I didn’t know any better, this is funny when you think about it given where I grew up, I bought a tube of white, China white. So, I really didn’t get it. And I went outside on the campus and decided I would do a landscape, and of course, I used that white. When I came in and I was looking at it, I was thinking, this doesn’t look like what I thought, and I showed it to you. I think you were going home, were about to go home, and I said, look what I did, I did a watercolor. You said, “…did you use white? …well, you don’t need to… just use the white of the paper, like a drawing….” But isn’t it interesting, I mean I grew up in this house looking at these things but not understanding the principle. I remember you said once that some of your early watercolors were done on a paper that doesn’t exist anymore. I’ve wondered about his paper. What do you think that paper was?

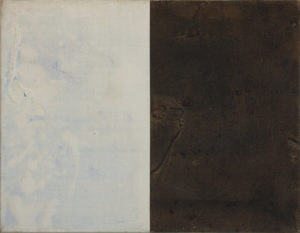

Wilbur Niewald: Well, that was probably the Strathmore Kid finish, but very soon after that, I went to Fabriano. The other watercolors that I do are the same, probably Fabriano, but I think that watercolor affected my oil. My oil painting in the ’50s and the ’60s is really indirect. That’s why it took me a while to learn in oil. I didn’t mix a color (directly), I made a color on the canvas through this idea of warm and cool, you see in layers, I would put a down a warm… warm generally meant forward and the cool meant back, and so I would make the color, and then come over it with another because I wanted to push it back. And you can see this on the canvas particularly there (gesturing to the oil painting over the fireplace) You can see all these obvious brush marks, one over the other, in other words, I was thinking much more of a total, and you can see how they became much more like where I am now. And basically, mixing the color, that’s what I meant when I said to adjust to the opacity and the transparency. I noticed that Donald Judd did write something way back, and for me, it was somewhat of a favorable idea from him, this was the 60’s, and, he said, something about the color… ‘accept the greens.’ All the greens (in my paintings) were not mixed with green, they were a mix on the surface, so they’re not exactly greens that I liked, but it’s the idea of controlling color in space that was more important than the idea of the color itself. The color is the result of the idea. In other words, the idea is in the illusion.

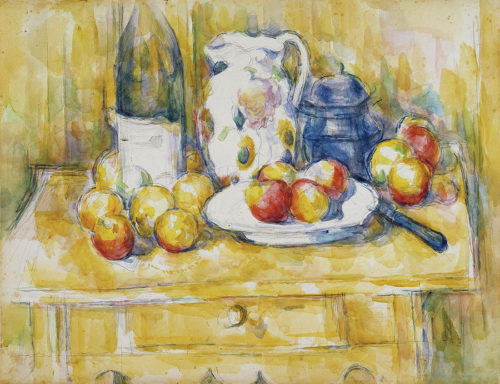

Janet Niewald: This, this is phenomenal, have you seen this one? (Referring to an image, The Dessert, 1900-6, pencil and watercolor on paper, 18×24.5 inches, private collection, in the catalog from the recent Cezanne, Drawing exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, NY.)

Wilbur Niewald: I have never seen that.

Janet Niewald: I haven’t either, and he clearly decided he didn’t want that fruit, and of course it’s watercolor, and you’re not going to erase it, but he just painted all over it, this is really interesting, it’s really beautiful.

Wilbur Niewald: Well, you know, his late watercolors, they were really developed. Oh, there’s the one that’s in Dallas. Actually, they were always very developed.

Jessie Fisher: Maurice Denis said that every day Cezanne would paint in the morning, but in the afternoon, he would go to the Louvre or to the Trocadero and draw. Denis said, “He (Cezanne) believes that it prepares him to see well the following day.” I thought that was such a beautiful way to think about the role of drawing, not a preparatory, but as a teacher.

Janet Niewald: Teaching your mind to see and to stay awake.

Wilbur Niewald: Yeah.

Afterward, Wilbur showed us the letter from Alice Neel. Beautifully scripted on a light golden onion-skin stationary paper. The letter thanked Wilbur and his wife Geraldine, for hosting her and remarked on Wilbur’s paintings which still line the walls of his self-designed Kansas City home.

I remember all the paintings on the walls,

the brain is a wonderful gallery

in which one deposits every painting that is visually interesting.

Alice Neel, 1974

Editor note:

Painting Perceptions is enormously grateful to Jessie Fisher for making this conversation available. I thank Jessie Fisher for this phenomenal gift to painters with the enormous amount of time and thought she gave to this project.

I was fortunate to meet Dan Gustin at Yale Norfolk where he introduced me the painting theories of Niewald. It gave me grist for the mill that summer in 1970. I wrote a book on teaching art from perception several years ago https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07VDW6Z5R and reference Dan and Wilbur

Martin, I just ordered your book and am so excited to read it! Thank you so much for your contribution.

Looking forward to hearing your reaction

The influence of the Niewalds extended beyond KCIA when Dan Gustin taught me the secrets for the primary color palette at Yale Norfolk that defined my work for the whole summer in 1970.

Wow, this was really great I loved it!

Catherine Maize was another student at Yale Norfolk 1970 from whom I learned a lot.She was a student of William Bailey at Indiana University. She is a highly regarded still life painter who shows at Paul Thiebaud. http://www.paulthiebaudgallery.com/

In this whole blog ,two words were never mentioned planer geometry which was the Hallmark of Cezanne.I of Italian decent was never taught to tell myself stories which I liked to believe.It took my father 20 years to mention “joey got a little better”. Although Niewald’s show at the Studio School was great I still had the reproduction till recently..Queens College BA