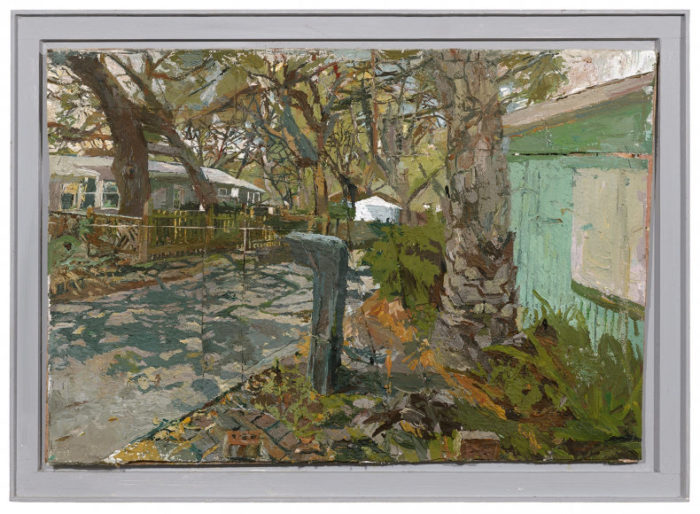

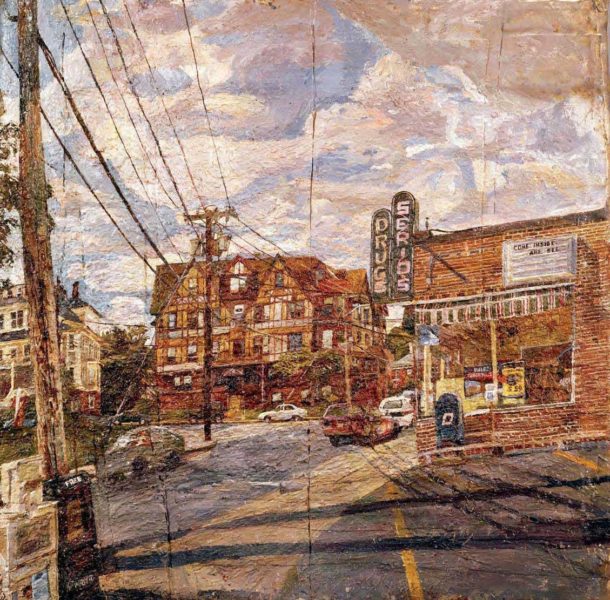

Houses on Jekyll Island, 2017, Acrylic on canvas, 23 x 34 inches courtesy of Betty Cuningham Gallery

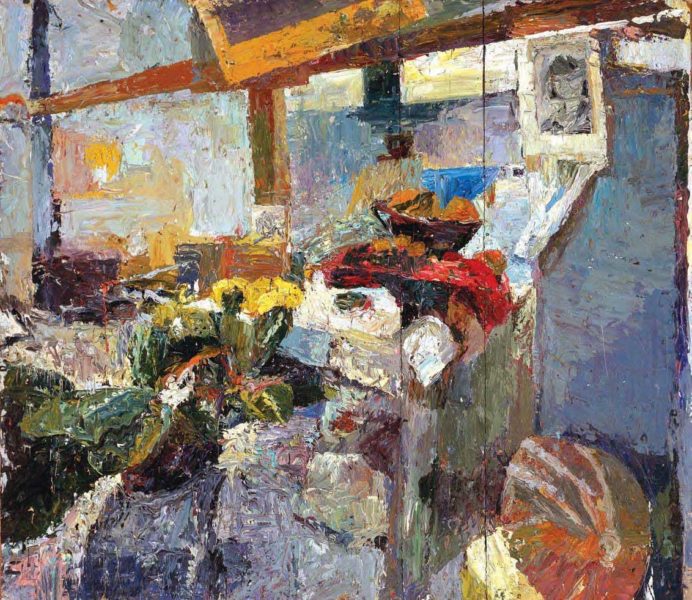

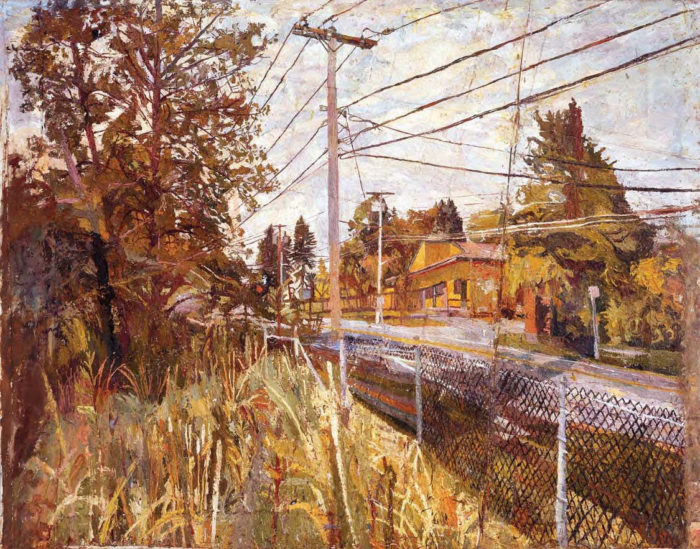

View from New Studio Window, 2012-2017, Oil on canvas, 65 x 63 inches courtesy of Betty Cuningham Gallery

I am very pleased to be able to share this recent telephone interview with Stanley Lewis. I approached Stanley Lewis a few times over the past couple of years to see if he’d agree to an interview but he declined likely due to his preferring to spend his time painting rather than interviewing. However, recently another opportunity came up for me to bother him once again and this time he agreed, in part to bring attention to his upcoming workshop at the International School of Art in Monte Castello, Italy during July 14 – August 4th of this summer. We talked at length on the phone and eventually he became more enthusiastic about our interview. We decided for the interview be in two parts; the first part centered around his teaching in Italy and related concerns which is posted here and the second part to come later to allow us more time and room to continue his discussion of his process and thoughts on painting. The second part will be published later this June.

Stanley Lewis, is a greatly respected painter who hardly need introduction but the Betty Cuningham Gallery website offers this bio for anyone who isn’t yet aware of his many professional accomplishments:

Stanley Lewis was born in Somerville, New Jersey on October 31, 1941. He graduated from Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut in 1963 with a joint major in music and art. His painting teacher was John Frazer. He graduated with high distinction. In the summer of 1962, he studied with William Bailey and Bernard Chaet at the Yale Summer School of Art and Music.

He received a Danforth Fellowship for graduate study and received an MFA from Yale University in 1967. His main teachers there were Leland Bell and Nick Carone. He began teaching at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1969 in the painting department, working under Wilbur Niewald for 17 years. He joined the Bowery Gallery in NYC in 1986.

Stanley taught at Smith College from 1986-1990 and then at American University from 1990-2002 working under department chairman Don Kimes. He retired from AU in 2002.

He has taught summers at the Chautauqua Institution’s School of Art since 1996 and was on the faculty at the New York Studio School until the end of 2011.

In Sept. 2004 he was in a two man show at Salander-O’Reilly Galleries. A long-time member of the Bowery Gallery, his most recent shows there were in February, 2005 and March, 2008. He was then represented by Lohin Geduld Gallery and had a one man show there October 13- November 13, 2010. The gallery closed in December of 2011.

From Feb. 17 through April 8, 2007, he had a major retrospective at the Museum in the Katzen Art Center, American University, Washington, DC. There was a smaller version of that show at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, Summit, NJ, that spring. In 2005, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. He has been elected to membership in the National Academy.

Stanley Lewis is currently represented by the Betty Cuningham Gallery.

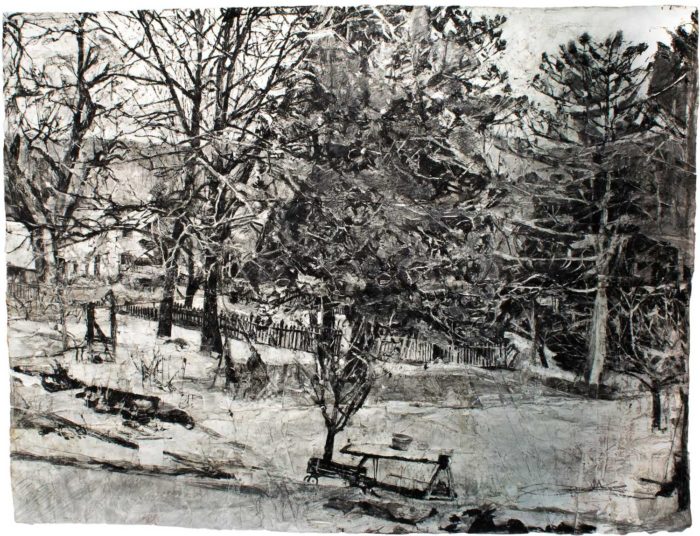

Stanley Lewis, View of Garden from New Studio Window, Winter, 2016, pencil on paper, 55 x 42 inches (courtesy of Betty Cuningham Gallery)

The painter Ruth Miller recently agreed to send me the following that she wrote about Stanley Lewis as an introduction to this interview:

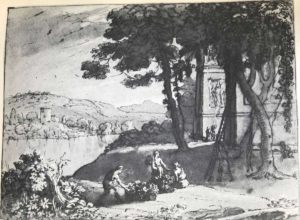

When thinking about Stanley Lewis’s remarkable work, many words rush in: passionate, unrelenting, obsessive, brave, true, generous, mad, visionary. But his work is also about the hard won image, about detail and layering, loving attention, spacial volumes, formal concerns, dogged devotion, about the concrete and about process. I was visiting the Barnes last month and while looking at those great Cézannes, Stanley’s paintings came to mind – it was Cézanne’s uncompromising search and realization – you know, that thing that brings a gasp and brings you to your knees – a push for (not perfection) but for what feels RIGHT, totally integrated and finally THERE – ARRIVED AT! For many of us, especially Stanley’s devoted students, he is a vital link to painters of the past: Rubens, Bruegel, Poussin, Claude, Constable, to name a few. He brings them back into the present with new and often surprising insights.

When looking at a Stanley Lewis painting or drawing, I feel renewed strength and hope, I feel less lonely, less alone, and for me that is a kind of fulfillment, certainly it is a deep reaffirming.” – Ruth Miller 5/6/2019

I also asked Thaddeus Radell, who has written about Stanley Lewis in the past as a contributing writer for this site if he could say a few words about his experience with Stanley Lewis:

As a painter matures and the long years in the studio grind on, studio visits and/or input from other artists, insightful and engaging as they may be, have less and less true impact in terms of the formal considerations of the paintings. The work has simply become so internalized that discussion of the actual pictorial devices in play is not, perhaps, as poignant as it would be at an earlier point in one’s history. A visit by Stanley Lewis is, in my experience, one of the very few outstanding exceptions to that general tendency. Stanley’s eye and mind have so united with the ‘deep state’ of painting that as he views and comments on one’s work, every moment of that sharing becomes somehow miraculously relevant to what one is actually doing, or trying to do. The matching of his poetic intuition and fathomless knowledge of what painting is with the brute strength of his experience at the easel results in lethal combination with which he manages to breach the wall of one’s internalized process and penetrate to its heart. During my last exhibition at Bowery Gallery, almost three years ago, I had the pleasure spending an hour or so alone with Stanley discussing my work. I found his remarks and insights piercing. And yet delivered in that endearing manner of his that puts one immediately at ease. Because he speaks to one as an absolute equal. His struggle is your struggle. And three years later I am still forging those thoughts into form in my daily studio practice.” – Thaddeus Radell 5/10/2019

Larry Groff: What is your approach to teaching your landscape painting workshops? What could someone expect to experience when studying with you at Monte Castillo.

Stanley Lewis: I spend a lot of time with the students who sign up to work with me. This tends to be on a casual basis like when we run into each other in the shared studio space. I’m set up to teach maybe two or three days and I give a couple of lectures. We paint outside, it can be a hard landscape to paint. It’s complicated and new for many people but the views are just fabulous and awe-inspiring. Where you look down and you see all the way across the Tiber Valley to the next town, Todi, with the farmland, trees and roads. Monte Castello is a small medieval hilltown, built like a fortress castle with a huge wall with an overlook where you can paint from. It can be a tough subject.

I paint with the students and I actually like some of the paintings that I do with the class better than some of my projects because they are chancier. I go around and see how they’re doing and that goes on all day. Teaching has helped me all during my life. I miss it actually because it can take me to interesting places I wouldn’t necessarily go to on my own.

LG: Monte Castillo isn’t too far from Assisi and all the incredible Giotto frescos at the Basilica of Saint Francis?

Stanley Lewis: Yes, We take day trips. We’re there for three weeks, so we go on these day trips, I think we’re going to Orvieto, Rome and Florence, all organized so we just go see all these overwhelmingly great masterpieces.

LG: Do you talk about the paintings with the students in front of the work?

Stanley Lewis: Yes and no. We are all together but we tend to keep it very fluid, I’ll often go off and find something that I want to draw and then drag somebody else into it with me. I’d rather draw in front of the paintings and encourage the student to do this rather than just talk about the paintings, like Leland Bell did with his students. Leland could talk beautifully. I’ve gone to listen to his lectures as much as I could but my idea about teaching is different. Drawing helps me to think about the painting so I encourage students to draw from the paintings and then I might walk around and suggest things. But I don’t usually lecture at length about the pictures on these trips.

It’s a great summer, any painting student at any age will like it, any age. The food is good and the company is great.

(above images from Christine Hartmann’s blog.

LG: So you and the students talk about painting, not in a formal way, just talking?

Stanley Lewis: No, not in a formal way, more in a kind of complaining artist’s way, more like how am I ever going to do this thing.

That’s my tone of voice and what I have to say. I’m always amazed by how hard it is to paint, especially painting from perception. It can be one of the most bizarre things you can do. I don’t find it an objective, clear thing to do. I’m overwhelmed by all that it can really involve if you are trying to get at the things I’m trying to do. So my basic strategy as a teacher has always been rather humble, the person who knows the least! I want to somehow show how amazing and difficult this all can be. However, I also say come on let’s go and do it anyway and hope that we’ll get through it. Oh my God! Let’s see if we can get through it! It’s only two more hours! And then we’re done. (laughs)

There are practical things I can suggest that can help students–Practical things like support systems like how best to hold down your picture. I mean that’s huge. I’ve always spent a lot of time worrying about how to put my picture up so it doesn’t move around from the wind. You’ve got to rope it down if it’s windy. There are other things about the setup that seem important to me like which side are you looking from, right or left? You’re constantly improvising in outside painting. You need to bring so much stuff. There are also all the straightforward things like organizing and simplifying your palette. Also, we talk about color, how the color is working. How stiff is the color, stuff like that.

LG: I was impressed with some photographs I saw of your outdoor painting setup. It looks like you sometimes build your own easel with found materials and sort of enclosure to help keep the direct sun off the painting so you could see the painting better and maybe to eliminate problems with the wind or whatever is just sort of surprising to see. You don’t go for the French easel or a fancy pochade box, instead you seem to prefer using that looks more like a lean-to or hunter’s blind.

Stanley Lewis: In Italy I will be using a French easel or fold-up easel just like everyone else. One thing to be concerned with is what do you do when it rains? Italy has these thunderstorms that come up all of a sudden that are incredible. You have to figure out ways to improvise so you can keep painting. I’ve used a plastic sheet that I would clip to my painting and then throw it over my head and this would allow me to go on painting, without having to stop. The weather system is different than we have here, it can be very dramatic at times.

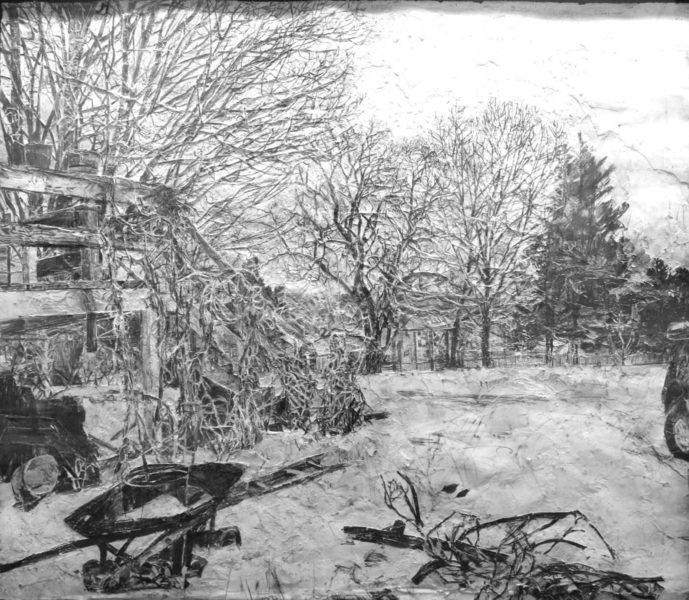

Stanley Lewis, View from Studio Window, 2003-4, graphite on paper, approx. 45 x 51 inches (From the Louis-Dreyfus Family Collection, courtesy of The William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation Inc.)

LG: When you paint from observation, how much is it about responding to the observable facts in front of you and how much is from some kind of personal invention that runs parallel to what you’re seeing? When painting or drawing such things as the negative spaces between tree branches and such – what keeps you from avoiding a formula but at the same time avoid being too prosaic?

Stanley Lewis: You are right. These are some of the problems and pitfalls with painting like this. My feeling is that it often feels like a horribly impossible thing to do but you somehow do it anyway. How do you do it? I have figured out is you do need to use some kind of formulas. I’m not afraid to say this anymore.

One formula involves figuring out the proportions and using a frame; that helps determine the relationship between all the tree branches and their surroundings–where the verticals and horizontals intersect–how to unify and relate spatially to each other. It can get very complicated; it’s difficult to explain. When you try to get everything working like this you realize that it actually can’t be done. How do you find a consistent stabilizing position? That’s what I’m interested in and that’s what I’ve been trying to do for my whole life.

The main person who’s involved with this that has influenced me with regard to this, but in a very different way, is Wilber Niewald. I really think he’s a key to perceptual painting for American painting. He’s the guy you should look at. I used to work with him at Kansas City Art Institute. Do you know who he is?

LG: No, Only a little, I’ve heard of him but I don’t know him or his work very well.

Stanley Lewis: You have got to find out about his paintings and if possible have an interview with him soon–He’s in his 90s. So my answer to this question flows out of many of Wilbur’s ideas. Wilbur is an interpreter of Cézanne and Mondrian. Wilber has had a beautiful career. It’s straightforward and develops very logically. He recently had a retrospective exhibition at the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. He was chairman of the Kansas City Art Institute for maybe 30 years. He hired me right out of graduate school. And that’s where we lived for 17 years, we raised our kids in Kansas City. Wilber Niewald was such a major influence on me. Of course I’ve gone my own way but his ideas really spoke to me.

I remember back in the 1970’s during a time when I was making these large abstract-like city paintings as well as sculpture, I had listened to Wilber talking to his students telling them to paint and draw what you see, a still life setup or something, as straight and as clearly as you can. I remember thinking, I’m going to try this. I didn’t agree with everything and I wasn’t sure I was ready for this but I wanted to try. I did, just a little but this led to a big change in the long run.

Still Life with Photograph of Karen, late 1970s, oil on masonite 48″ x 54¾”, Collection of the artist

I didn’t visit his studio that much but I went there once and saw his huge painting setup with three geranium plants taking up an enormous area and this incredible painting which was completely covered with this beautifully painted complicated foliage of the geranium plants. But Wilber, who is a very interesting person–quiet, steady, and forceful, was telling me that he just noticed that in this painting the geranium weren’t in the right position, weren’t in the right place for the painting–they were off by about a half-inch and that he needed to move them all over a half-inch. This meant, of course, that he would have to repaint everything to move it over. This was staggering to me; I couldn’t believe it. It was a major revelation but has since become what I do. To get everything exactly in the position it needs to be, to have everything working together in the right place. It can be overwhelming to have to repaint things so often so I deal with these problems with my particular formulas. Which is basically– when it doesn’t look right repaint it! I find my way through these tangles by using a system that kind of organizes things, to better know where things are–their position, where they start and end, what is inside the frame and on the outside. One thing is that there is always an imaginary frame to determine the boundaries of the scene for the painting.

LG: By frame do you mean using a viewfinder? Is that what you mean by frame?

Stanley Lewis: Yes, I use a Viewfinder most of the time, especially with these big setups, the view finder is the key. Sometimes I can use just use sticks, two sticks but you can also lay the sticks out or lay rocks out in the actual landscape to mark where the painting is going so your eye knows where things end.

LG: What about keeping your head still, so you’re painting from the same vantage point every time. To really be accurate wouldn’t you need to put your head in some sort of vice grip so that you don’t change your position? (laughs)

Stanley Lewis: That’s the key to the impossibility of it all! Because you don’t actually have a vice grip, you’re looking is flawed. The whole thing that you set up to be clear about, like where the painting starts and stops is in flux. It can make for an impossible situation. I work for weeks trying to get something right and then get to a certain point realizing that that is not going to work and I need to change the boundary. Another thing is that I’ve figured out I have to paint everything clearly and realistically in order to be able to see where I am–not just schematically.

I asked one of his former students, Timothy King, if he would be interested in writing something about what it was like to study with Stanley Lewis for this first part of the interview with Stanley. He enthusiastically agreed and sent me the following essay. Timothy King is a Illinois based painter who has been instrumental with the running of the MidWest Paint group.

My studies with Stanley Lewis

By Timothy King

I studied with Stanley Lewis over four semesters at Kansas City art institute from 1978 to 1980. I was a KCAI painting student at a wonderful time and worked with four other great painters at KCAI before taking Stanley’s drawing class. But once I was there with Stan, it became my dedicated mission to study painting, drawing, and sculpture in his studio. In my third semester of study with Stanley, he was into a transition phase, so I was able to take in his ideas as they spanned two sides of his career. Those who got there too early or too late may only have experienced half of his trajectory as a painter. In the 1960s and ’70s, Stanley taught his kind of structuralist abstract-figurative monumentalism that he admires in the work and ideas of Leland Bell. Stanley still works to this day with these ideas in studio paintings and with even more evolved ideas and forms. Stanley doesn’t show this work as much, so it’s somewhat underground and sadly not reviewed as much. In my last semester at KCAI, I was witness to a reinvention of Stanley’s ideas that remains a part of his predominant style of today. He refers to his work now as more aligned with an approach of seeing the particular about nature and less about the ideas about the universal in nature’s forms. Stanley attributes this change in working from his time with Wilbur Niewald at KCAI. Both painters think in terms of “the particular” in looking closely at nature in building up the painting.

Stanley’s paintings were always monumental. They are a treatment of sublime structure; A natural process of destruction and creation at once. I’m thinking how wonderfully gouged out and collaged together the paintings are; so unlike any other painter I’ve experienced in his constancy in attacking with paint. Stanley’s paintings have always had the thickness of texture and full, vibrant color, built up in heavy and dripping and gloppy layers. Up close you see an entirely abstract experience. From the construction of detail, he forms his intricate abstract monumental vision. And so alike are the large gouged out graphite drawings that he has become so well known for since the ’90s and 2000s. I was pleased to see Stanley is still sculpting. In the ’70s and 80’s he was doing larger figurative work in plaster and smaller carved wood figures. Stanley set up a sculpture studio at the end of each semester, so I was able to do 3 figure sculptures in all with his help. Stanley taught me to build from the center at the armature working the pelvis and backbone out to the skull, arms, and legs. And not to depend only on the profile views. It was how he worked conceptually without a model but also with a model. I was able to see his developments back in the 70s covering his ideas about Frank Auerbach, Picasso, Helion, Giacometti and Leland Bell to the transition of his 90s and 2000s solid full blown Courbetist of today.

It’s been great staying Stanley’s friend and conversing about these gradations in his work over the last 40 years. Stanley always talked about odd things like spatial reversals and inversions and weird perspectives he discovered in the old masters. His ideas, in turn, got me intensely interested in how he saw things, as only he could convey about the hidden structure of painting to his students. Back then at KCAI, Stanley loved to teach about the great still life painters from the golden age of Dutch art and how their paintings are so perfect yet deceptively unorthodox. He showed me in these Dutch works the perception of multiple readings of perspective; warning us to look out for the fictional view and the actual underlying reality; to draw copies and make an analysis of the space beyond the picture frame to see beyond the finished facade. Stanley taught the art of “simultaneity” to discover the most significant aspect of painting’s history barely touched upon in traditional art history lessons. He was the sole source for my love of the “two-table idea” that I often discuss, to explain Cézanne’s strangest still life’s, and how these are models to understand the Dutch still-life that contains a disguised two table construction, revealed in a seamless single tabletop fiction. This model serves me as the lesson of all great painting where spatial structures are building out of inventions between reality and fiction, flipping the space, so foreground and background change positions. Among others, Stanley showed me Pieter Claesz and William Claez Heda who painted around Cézanne’s fragmented arrangement, hiding and healing the setups divisions and fractures in the final rendition.

In class, I always loved how Stanley demonstrated an immense comprehensive grasp of drawing. One demonstration of Courbet’s Portrait of P.J. Proudhon, Stanley showed how Courbet constructed a little girl pouring out her teapot by the way the ground plane and porch steps created a flipping motion into the girl’s body, forcing an action ending in the twisting wrist holding the tipping teapot, thus sending out the flowing liquid. I still have the newsprint demo sketches he did showing the underlying mechanism of Courbet’s ingenuity. And I have some of Stan’s schematic demo’s he would do just for me of Corot’s women, showing the way their clothes are always off center, and theorizing that Corot asymmetrically dressed his models with shifted garment positioning turning their clothes into a building facade to create dual readings with the real and the false perspective.

Everything Stanley teaches is not what you had learned before you got there. Through his lessons, you realize you never really understood as richly before. He demonstrated those ideas to be vivid and enduring. Stanley, in his last and best experience for me at KCAI, taught about his new interest. He started working through a view-frame. We worked with the frame at the same size as the canvas, like the Dutch masters did and Van Gogh, leading me to isolate on the extremes of abstraction in my vision and unlearning my preconceptions of visual relationships. At first, Stanley had me, as he was starting, drawing through an attached view frame made of sculpture armature wire taped to the drawing pad. Holding the pad in one arm up to my face and looking through the frame the objective was to view with my left eye and observe the original projected image as it naturally crossed over, superimposed onto the pad with my right eye. Then we traced it out like the way a camera Lucidia works, but more interesting in the abstract shapes, the directionality of line and forms that held very unpredictable distortions as the eye moved all around the frame. When I started to work on larger canvases about 36 inches wide, I learned to see this new kind of monocular vision and in the near corner where both eyes meet to paint with binocularity. Later in grad school, I shifted to a purely binocular approach. I was gratified to find out Stanley had been working with stereoscopic vision too. Stanley always taught what he used to call “the invention of the painter’s form.” It was the undoing for me of my traditional photographic assumptions about art. Working through the frame was a more painterly invention to me. Stanley still paints through the frame as I sometimes do to stay in tune and in that particular zone. It teaches me to see the unforeseen of the picture plane.

I could go on and on about my lessons with Stanley Lewis. These are just the highlights not getting into the nuts and bolts. I know many of Stanley’s former students who had different and equally valuable experience working with him. I always want to hear about these other parts to Stanley’s brain for inspiration. In my visits in person and conversations on the phone Stanley unusually leaves me with new clues and points of interest showing some of his current thinking. These tips become challenges for me and over so many years has reminded me I’ll always be a Stanley Lewis student.” – Timothy King 5/10/2019

What a great and insightful article on a truly great painter. Everyone who knows Stanley’s work over the last forty years knows in their hearts he is a true genius and completely unique in American painting today. People should run, not walk to study with him in Italy. This Summer in Italy 2019 is a once in a life time chance to not only work with Stanley but live with him for three weeks; and to take advantage and learn from this amazing painter in ways that would be impossible in a normal school situation. Stanley’s depth of painting knowledge and incredible passion for painting are unparalled.

Thanks Larry for a great article and bringing such a beautiful focus to the man and painter we all love.

Dan Gustin

I have had the honor of studying with Stanley Lewis many times over the last decade. He is truly the real thing when it comes to teaching painting from observation. Stanley’s passion for painting is obvious as soon as he starts talking. His approach to painting is filled with humility and a sense of urgency to push forward and make something happen in the process. Drawing becomes essential to his ideas about space. During a teaching session with Stanley, so many great masters become a part of our present day experience; Cezanne, Derain and Constable among many others. Stanley inspires us painters with his conviction to “carry on the task” of painting from life!

Tina Kraft

I was a wonderful student of Stanley Lewis in the 1970’s. Can i.have his phone number again as I was painting in.Peru for years?.he will be happy to.here from me as we kept it in touch… gracias