I am very pleased that the renowned painter Robert Birmelin was able to join me for a telephone interview recently and thank him greatly for his time and involvement in sharing his history, process and thoughts on painting.

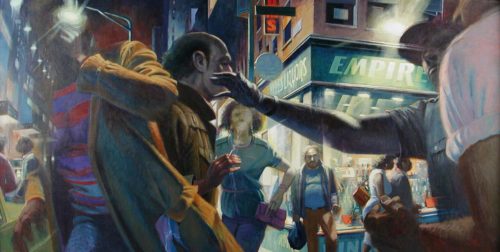

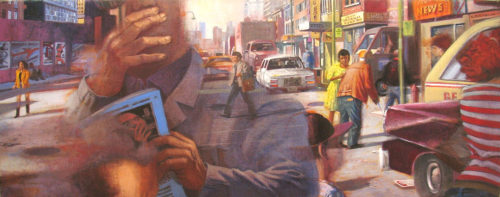

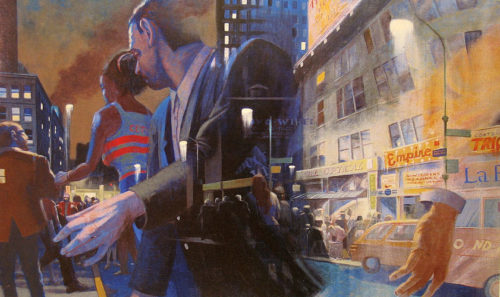

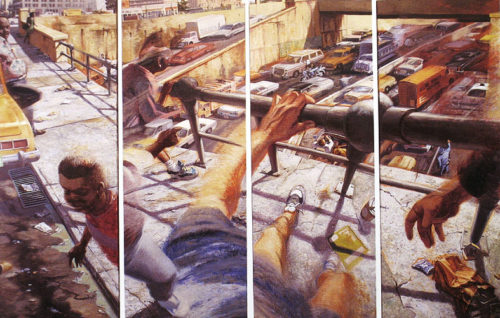

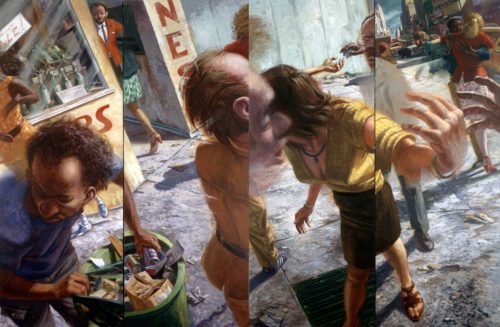

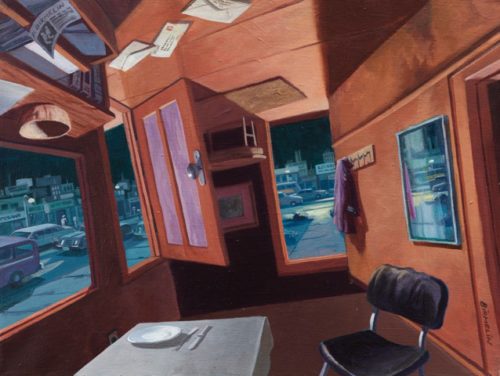

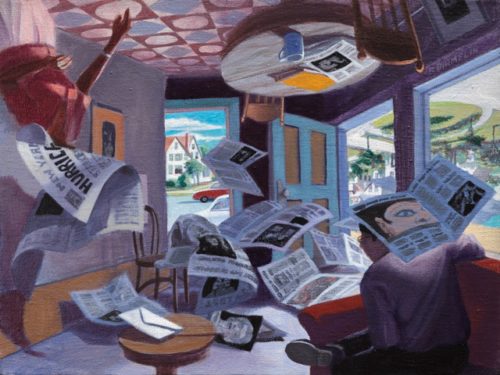

Robert Birmelin has long been painting highly personal, realist cityscapes, which he continues to explore through complex representational devices. Independent of photography, Birmelin constructs his detailed urban scenarios mentally. Placing himself in the role of pedestrian observer, he frames a street scene as a momentary perception: looking over people’s shoulders, for example, glimpsing events through their hair, or, in dramatic works from the ’80s, watching from between gargantuan fingers, through which we see streams of jostling figures. In the ’90s, he turned to psychologically dynamic interiors, introducing Magritte-like tropes–upside-down passages or interpolations in scale.” – From P. C. Smith’s review, “Robert Birmelin at Luise Ross” Art In America, February 2007

Robert Birmelin has works in collections in leading museums such as The Metropolitan Museum, New York, NY; The Museum of the City of New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Nagoaka, Japan; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; The Library of Congress; the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American Arts; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; the San Francisco Museum of Art; and National Academy of Design.

He is the recipient of many prestigious grants and awards including a Fulbright grant in 1960 followed by a Prix de Rome at the The American Academy in Rome in 1961. He has received Childe Hassam Fund Purchase Awards, American Institute of Arts and Letters in 1971,1976 and 1980; the Carnegie Prize for Painting, National Academy of Design in 1987; Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts, Rhode Island College in 1996, and the Altman Prize for Landscape Painting, National Academy of Design in 1999. He has had numerous solo shows at major galleries such as the Luise Ross Gallery, New York, NY, Peter Findlay Gallery, New York, NY, The Columbus Museum, Columbus, GA, Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco, Claude Bernard Gallery, New York, NY, Alpha Gallery, Boston, MA and showed his works during the 1960’s in the Stable Gallery, New York, NY.

Birmelin attended the Cooper Union and Skowhegan art schools and received B.F.A. and M.F.A. degrees from Yale University. A 1960 Fulbright grant followed by a Prix de Rome in 1961 enabled him to study for a year at the Slade School in London and to spend three years at the American Academy in Rome.

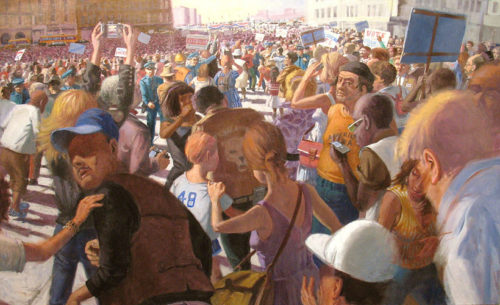

A realist with a fascination for existentialist literature, Birmelin is perhaps best known today for his panic-tinged New York crowd scenes. He draws his imagery from the disparate environments of New York City, where he teaches, and his summer home on Deer Isle, Maine. Birmelin controls visual experience through viewpoint: the panoramic sweep of his light-suffused landscapes provides the serenity of distance, while in the crowd scenes he crops images and truncates people at picture edges to create an immediacy that perfectly coincides with the compelling urgency of his subjects.

Virginia M. Mecklenburg Modern American Realism: The Sara Roby Foundation Collection (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1987)”

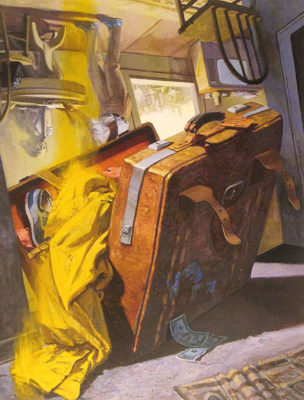

It is not unusual to find that a relative or friend’s memory of a past event clashes with one’s own. Indeed, how often do two witnesses to the same crime contradict one another as to what really occurred? As an artist, I found myself seeking a visual structure that would be an active metaphor for such a state of mind – a structure continuous and spatially rich that initially seems to offer an uncomplicated, expected orientation and then self subverts, challenging the observer to recognize the claims of another equally visually insistent counter-reading. Our minds are restless, making choices, fluctuating between possibilities as we strive to interpret, to judge between contending truths. These paintings live in mid-thought, in the space of that uncertainty – an all too familiar space in a world of bewildering choice.” – Robert Birmelin talking about his work at the 2012 Winter Contemporary Show at Old Print Gallery

Larry Groff: What were your early years like, and how did you decide to become a painter?

Robert Birmelin: Like many kids, I always liked to draw and by good fortune, I had a very cultured and helpful high school teacher. Coming from a working class family in northern New Jersey, I wasn’t that clear about going to college. She told me about Cooper Union, I applied, was accepted and that made all the difference in the trajectory of my life. I attended 1951 to ’54.

LG: Their tuition was free back then, right?

RB: Yes, it was free. They again have a plan for free tuition in ten years. They’re going to work toward it. I think that’s good. It’s a wonderful institution, and its founder and his idea about free education for working class New Yorkers was a noble one. When I was at Cooper, the Whitney Museum was on west 8th Street, near Cooper Union, and I became well acquainted with the art happening at the time such as de Kooning, Kline and the rest of the avant garde as well as Hopper and the Social realists. Also, our teachers at Cooper were oriented toward the Abstract Expressionist milieu.

I went to a meeting in the last year I was at Cooper and listened to a recruiting talk by Bernard Chaet, a faculty member at the Yale University Art School. Josef Albers had recently become head of the school and was in the process of changing its nature completly. I went to New Haven with seven other Cooper Union students to show our work. I remember vividly, it was the second turning point in my life. We went into an empty classroom and were asked to stand up against the wall and put your work in front of us on the floor.

We’re waiting around, and in comes Josef Albers, in a gray flannel suit with a yellow tie, shock of white hair, with his assistant. He looks around silently. Looks at the artwork around in the room, mostly drippy, expressionistic work, mine included. And he says, “Vell, who vill speak first?” Nobody said a word, and he looks at me and he says, “Vell, boy.” Extremely nervous, I tried to start talking about my work. I got about ten seconds into it, and he just cut me off and went into a five minute lecture about how New York painting was rotten, how he hated the drips and so forth.

I was devastated. Here I am, this 19-year-old kid, and just been blitzed by Josef Albers! He then looked at other Cooperites and left. So we’re all standing there, in a few moments he comes back in and he looked around the room at each person and then he pointed to me and said, “You.” then he points to two other people, “You and you, go see the secretary.” We were now students at Yale. Can you imagine that for an application process!

LG: What a difference from today!

RB: Anyway, that’s how I got there. At Yale, Bernard Chaet was a very important teacher, who later became a friend and advocate. I started drawing with him, and that was very constructive and important. But I had difficulty painting. Albers, in his talks and critiques, was very clear about what he was about, but I couldn’t adapt myself to it. So I fled, as students often do, to the print room and got very involved in making etchings. My enthusiasms were for Goya, Redon and Max Klinger among others. I made a series of etchings and I graduated in 1956 on that basis rather than painting. Those prints were the first works that I really felt were in my own voice. I graduated from Yale in ’56.

I had my BFA, but was tired of school. During that summer I was doing some commercial artwork in the city, probably not very well, and not well paid. I then got a draft notice to report in a couple months. I was drafted in January ’57 and I was in the Army for two years.

LG: Did you get a strong traditional figurative training?

RB: I’d never painted from the figure; not at Cooper, not at Yale. It wasn’t available, though I’ve drawn from the figure a great deal. I had seen Edwin Dickinson’s paintings in the 12 Americans show at the Museum of Modern Art, sometime in the mid-’50s. I went to study with Dickinson for a couple of months at the Art Students’ League. He was a very interesting kind of man; through him I got an insight into tonal painting, about building a painting with patches of color rather than line. This was something I couldn’t have gotten from anywhere else.

LG: Dickinson was such an amazing painter.

RB: He was a marvelous exponent, not so much as a teacher. This had more to do with his painting–building a picture without line, with patches of tone and color. That was very important to learn for me, though I couldn’t use it immediately.

When I was finally discharged in January 1959 I was admitted back into Yale’s MFA program. During that year and a half I made prints, and very large drawings. For the final review of the year there were no formal exhibitions for students graduating, but rather you put your work up in an empty classroom and it was looked at by the faculty, then you took it down. I had made these very large black and white drawings, seven-foot drawings on very crummy photographic background paper. Bernard Chaet brought Eleanor Ward, owner of the Stable Gallery, in to view these drawings. In the 1950’s thru the 60’s, the Stable Gallery was the premiere avant garde gallery of that period. They showed the first Rauschenberg’s, Abstract expressionist painters and even early Warhol.

This would have been in April, May of 1960. In April I married Blair, my beautiful and smart wife, who has been my most loyal advocate and most perceptive critic ever since.

Eleanor Ward comes in and looks around and said, “I’d like give you show.” I was so naïve Larry. I thought, “Oh, that’s really nice.” Here’s somebody who’s running one of the best galleries in New York coming in to see this graduate student show and says, “Oh, I’d like to give you a show.”

I said “Yeah, that would be nice”. Then I thought, these drawings are all on crumby photographic background paper that tears every time I unroll it. When she left I carried them home and stuffed them in a garbage can.

LG: Oh my goodness.

RB: Blair and I got a positions teaching that summer at the Yale Norfolk Summer School. During the summer I painted a whole damn show in black acrylic on canvas, white canvas. It was a black and white show. I painted 15 big paintings in eight weeks, some good enough to exhibit. We got back home to New Jersey, my father helped me stretch them in the garage and we shipped them off to gallery in August. The gallery didn’t open until September, but they were stored. I had a Fulbright scholarship. Blair and I were scheduled to leave for England, the ship leaving at the end of August. We were on the boat, we’re going to London when the show went up in New York, it gets reviewed, and I thought, “Oh that’s really nice.” I was so naïve. It was a time to enter the scene… I should have been there. Right?

LG: Sure, right.

RB: I should have been meeting people, making contacts but that’s the way it is sometimes. When things come easily, sometimes you don’t know what’s going on. Well, I’ve had a history of lacking the entrepreneurial spirit.

LG: So you received a Fulbright and the Prix de Rome in the early 60’s. How did that influence the directions you took after living in Rome and London?

RB: We spent a year in London, where I started to paint. I felt released from the entire Yale environment. To start, I decided to paint colors they way I saw them rather than worry about color theories.

LG: And you were at the Slade School there?

RB: I was assigned to Slade school at the University of London. I drew from the model there a couple of times. They have this tutor system; I went to see my tutor, who turned out to be Andrew Forge, who later became the dean at Yale.

LG: Was Coldstream also there at that time?

RB: Yes, he was there but I had no contact with him. My tutor, Andrew Forge wasn’t that interested in Americans at that time. Frankly, he sort of brushed me off. I didn’t mind, because we’d found a rather nice apartment and I did a number of large paintings of crowds, the first crowd pictures I did. Also we traveled to the continent, Belgium, Netherlands, France and Spain. It was my first sight of the “real thing”, so different than the reproductions in art books. Later we also traveled in Germany, Switzerland and Austria and the Scandinavian countries.

LG: What painters from art history did you see that have been most central to your concerns?

RB: There are so many… a big Daumier exhibition was the first discovery we made after arriving in London. It made a lasting impression on me. To risk sounding like a laundry list, in no particular order I would say: Breughel, Goya, Rembrandt (particularly the etchings), Signorelli, Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, Degas, Caillebote, Piranesi, Max Beckmann, Picasso’s Analytical Cubism, Futurism, Magritte, and the early films of John Cassavetes (“Shadows”). And at certain moments Balthus and Bacon.

In the 60s, Balthus, Giacometti and Bacon were really the contemporary figurative artists that one tended to look to–painters for suggesting ways forward. Of course this was all set against the context of the dominance of abstract and Pop art.

In American art schools their work seemed to suggest a way to something else, something different, something more radical… Most certainly, the model of Balthus of rang through American figurative painting, in that period and later, probably sometimes in embarrassing ways

After London, I got a grant to go to the American Academy in Rome and we got to Rome in 1961. I was fortunate enough to continue there three years.

It was still a kind of Ivy League-ish kind of place. More weighted toward art historians, archaeologists, philologists, and so forth and so on, though, there were several painters, composers and writers–some very smart, interesting people. I took over Lennart Andersen’s studio as he was leaving. It was a big, beautiful studio on the second floor on the highest hill in Rome, with a skylight that had been built for mural painters.

LG: Terrific.

RB: It took me a long, long time to realize how I was lucky beyond belief. Anyway, I started to paint there. I painted a whole variety of paintings influenced by many sources; a little de Chirico, Cubism, Futurism Surrealism and even the emerging Pop Art. Of course we were also devouring the great historical works of Italy and the rest of Europe on our frequent travels. I was doing a lot of drawing. Drawing was, and is, a major part of my production, maybe the best part.

In the last years I was at Rome, I did several large paintings, six or seven foot paintings of different kinds of multiple figure situations and also some interiors. I was opening up as a painter in a way that I hadn’t before. That was good.

You asked me before about what influenced me; there are works that influence you, and there are other things that you just admire immensely. I’ve had certain reproductions of Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino, that had been up on my wall for years. Being in Italy and standing before them is so, moving and amazing. There are a couple of pictures by Rosso,” Moses and the Daughters of Jethro” and his phantasmagorical altarpiece in Volterra with their jagged forms, anti-naturalistic space and color dissonances that engaged me deeply.

Another case was Caravaggio’s “Seven Acts of Mercy in Naples. Do you happen to know it?

LG: I’m afraid not.

RB: Go ahead and look it up sometime. I’ve drawn it several times. It’s an impossible, impossible painting. It made me realize that certain works, which disregard existing canons, look like they have something “wrong” with them. But that “wrongness” gives that image its power.

There’s a painting, in the Metropolitan Museum, by Ludovico Carracci, it’s a dead Christ mourned by the Virgin, St. John, and saints. Every time I go to the Met I look at it. Christ’s broken, dead body is cradled by Mary and is painted in this painfully naturalistic way. But, all the other figures in the painting look like they come out of a different world. Was he experimenting? Perhaps… It’s disturbing. It’s the clash of two kinds of incompatible worlds. The tension between the two holds me every time I see it.

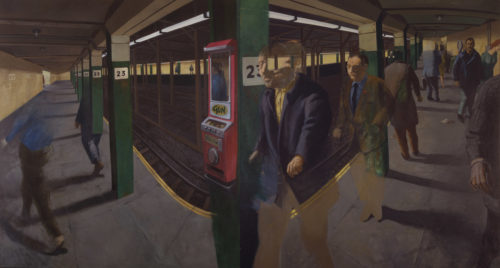

Seeing Max Beckmann Among Commuters Near Penn Station, (Large Version) Acrylic on canvas, 48 in x 78 inches, 2008

LG: I’m curious to hear more of your thoughts. Some painters I’ve talked to prefer to draw inspiration from the Early Renaissance painters, like Piero, as opposed to the Mannerists. It seems less common to have the same degree of connection with Mannerism. I’m curious if you have any thoughts about that.

RB: I think it’s more about temperament. I’m drawn to works, which have certain kinds of tensions within them. Tensions not only formally, but psychologically as well. I’m drawn to works that have interior stresses and surprising interior dislocations. I think they often are located at key points in art history. Beyond that, these works correspond to an inclination in myself. Does that answer?

LG: I’m curious because you often hear complaints about Mannerist painters being too bombastic and prefer things to be more sedate, detached. I often get suspicious and think, “Why not? It’s not just theatrics. It’s human to show feelings, even if they get carried away. I’m curious to hear another side of it. The Sienese painters, Piero and Giotto are admired for their relevance to modern aesthetics but other forms can be inspiring as well.

RB: I know that, and I respect the remarkable achievements of the artists you’ve just been talking about. I love the Duccio Maesta Pieta. But … We’re all partisan, as an artist, I know I am a partisan. The works, which I respond to, are those that pose questions that I myself, would like to be able to answer.

LG: I think I understand.

RB: To just move out of Italy for a minute, Here’s another example; paintings by Albrecht Altdorfer–which I saw at a monastery in Austria–the Saint Sebastian paintings. These paintings are imprinted on my mind. I keep reproductions of them around. The spastic movements of figures, the claustrophobic landscape–I’ve made drawings from them and looked at them again and again.

Again, as a working artist–as someone making art, what resonates are works that you absolutely need in some way. Perhaps it is the kind of energy, the charge they communicate. I look at the Pieros, in Arezzo, they’re incredible, noble, wonderful things. I admire them, but I don’t… I can’t inhabit them quite the same way; it is my limitation.

I think each artist creates his own art history, one of affinities. The academic art history is one thing, but an individual artist’s art history is very different. It’s made up of a patchwork of answers to questions that you have within yourself.

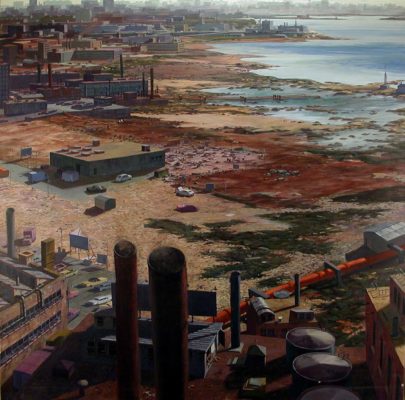

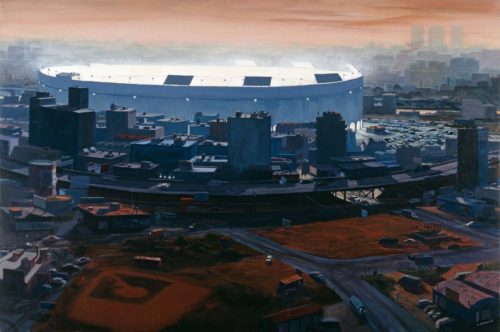

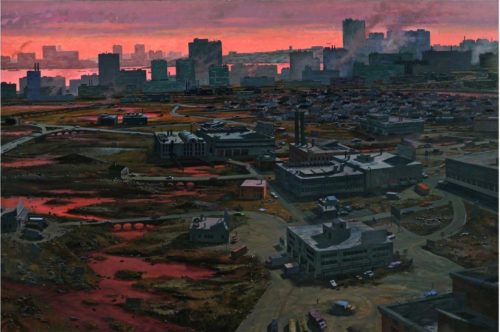

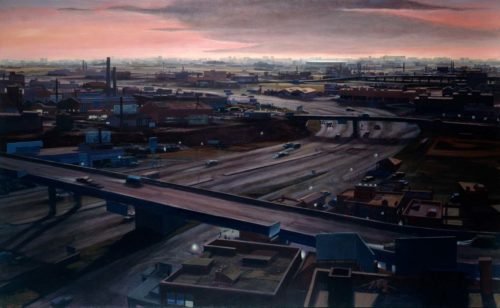

There are many kinds of work I admire but there are a smaller number that have truly affected me. Again, talking about affinities, in the ’70s I did a lot of landscapes, invented landscapes. They were triggered by my coming across a book on Caspar David Friedrich. Of course, my landscapes were urban, the area around northern New Jersey; the meadowlands, the swamps, the highways and the remnants of industry. But in the back of my mind was Caspar David Friedrich painting of icebergs.

LG: Some of those urban landscapes from then, the ones that I remember, I don’t have it right in front of me, but … They were just these amazing, this kind of almost aerial views of this huge areas of this sort of industrial landscape, and freeways, and amazing light, very, very dramatic scenes. How did you go about making them? Are these total inventions or did they come from something else?

RB: I’ll tell you how it began. I was with my family, my wife and my two kids. We spent quite a few summers up on the Maine coast. At a certain point in the ’60s, I wanted to purify my sight. I went out on the beach every day and within a couple hundred-yard distances, I’d paint something. I painted little panels for a long time, and then bigger ones, just trying to get the light. Get the light, get the feel of it just as simply as possible.

But, after a while I began to imagine a city on the sandy, rocky water’s edge. I built a city into one of my Deer Isle paintings. I imagined it and that was the start of it. I began making them up. Of course my memories of the meadowlands, the oil refineries and the role that driving all my life in New Jersey’s tangle of highways played. There was a peculiar pleasure in making all this up. Getting the landscape started and then beginning to place buildings on it–here, there. Highways, how do they connect? Feeling like God, ‘I don’t want that building there. Let’s paint it out’–let’s move the road from here to there. Great fun.

LG: Right, right.

RB: They’re completely fabricated in my own mind. And my own way of painting is that I begin very loosely and test locating elements loosely. I inevitably make a lot of changes as the painting grows.

LG: Why did you stop painting these landscapes? You then went on to paint the street scenes, right? You never painted scenes like that again, as far as I know.

RB: Yes that was through the ’60s and ’70s. I wanted to paint figures. I’d been painting these straight landscapes then on to do those invented landscapes. I wanted to paint figures but I didn’t know how to make them do the things I intuited must happen to be fresh and forceful.

But I learned from painting the rocks on the beach. I learned how I could place figures in depth–to think about how my eye tracked its way through the complex grouping.

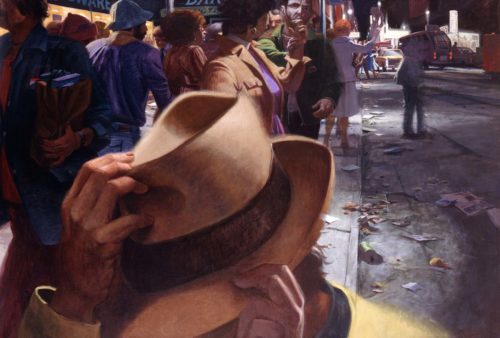

City Crowd – Cop and Ear, Acrylic on canvas, 48 in x 96inches, 1981, Collection Metropolitan Museum of Art

LG: You often lead the viewer’s eye through your paintings in unexpected ways such as looking past busy street scene with vaporous, moving crowds to focus on one solid elements like a foot with a bright red shoe, a woman in the distance in sharp focus or a dog dragging a leash. It’s hard for me to think of another painter who consistently offers such visual surprises. What is the attraction of this for you?

RB: I’m interested in movement, in the transient moment of noticing. In the eye as it selectively focuses within a changing, often overloaded environment.

LG: Very interesting.

RB: I was looking at how people were being on the street. I made a lot of sketches outside. I mean, really scribbly stuff, you know? But, that I could take back and expand in drawings and later paintings. I wanted to convey not only that the people were out there before me, but they were surrounding me. That the viewer was, by implication, a participant in whatever was happening. Of course, very often on the street, you’re not always sure what’s happening. There can be anxiety, in participating.

One reason I bring some of the foreground figures are up so close, is to promote that sense of potential involvement.

One day, a friend of mine … Do you know the artist Paul Thek?

LG: No, I’m afraid I don’t.

RB: He is a hero of the gay counterculture. He was one of many from the generation of artists who died during the AIDS scourge in the late 80’s. He was also a wonderful innovative artist.

RB: He’d been a classmate of mine at Cooper. He comes in the studio. I’m working on a mid-sized painting. He said, “excuse me but you should paint big.” I thought about it and started to paint a couple of these six by nine foot pictures, which was about as big as I could get out of my third-floor walk-up studio.

And they were better! We got into the ’80s when there was a revival of figurative painting. I produced an immense amount of work, and not by painting fast, either, because I’d spend a long time on a painting. I just spent a hell of a lot of time in the studio. My energy level was high.

LG: How you go about starting your painting? Do you make a lot of preparatory studies or just dive right in?

RB: I would have drawings and sketches, really planning out the layout. I’d begin very roughly and openly and change everything a lot in the process of painting. I moved figures from one side to the other, changed them from male to female, brought them forward, and pushed them back. I felt at that time, I could move everything around in the painting, all the time. That was from my heritage with the Abstract Expressionism I experienced as a very young student at Cooper.

The original drawing would usually be left pretty far behind. Somehow I wanted to exist in that invented space, to feel it physically as I worked.

LG: Was surface much of a concern with that? You’re working in acrylic, so, would you build the surface up? Or would you scrape it down?

RB: I would usually paint over it, or sometimes I’d just white out a section and repaint, or do whatever I had to do. I think a conservator would be appalled. But, it was a way I could work.

That whole series concluded in the early ’90s with several 7 by12 foot paintings that had four panels each. The four-panel idea was to more markedly express duration. The dislocations between the panels were sometimes slight, and sometimes major–suggesting a kind of flickering moments of noticing— noticing behind you, left, right, in front of you. Those are some of the best ones I’ve made,

RB: I worked on the crowd pictures through the ’70s and up to the early 1990s. But things happen; life changes you.

I had an, emergency bypass, nearly a heart attack, not quite, in ’93. I’d done these very large paintings, and probably was at the end of that cycle It gets you thinking when you’ve almost died, I began to think about my past, my family, my parents, the relationships between them and myself, and the people around me, my wife and family. I wanted to change, to but down the baggage and begin anew.

I had a talk with my sister about something that happened in our family when we were adolescents a very important thing. Her interpretation of what that event meant was completely opposite to mine. I was also wondering, how can there be those two views? How can there be this clash of opinions about what’s real within us all of the time.

We’re convinced we’re very good people, but we do bad things sometimes. But, we’re still convinced we’re good people. I wanted to find a way to suggest that double-ness, that inner restlessness of interpretation, contrary interpretations. That’s when I started to experiment with these interiors, many of which are double headed.

RB: Nobody liked them. I pursued that for quite a while. A picture, which would always be irritating, would look initially quite right, but oops! It can’t work that way. When it’s reversed, the same thing happens. I wanted a picture to have an inner restlessness, which was parallel to the inner restlessness I feel myself about so many of my relationships. That was what ran through the ’90s.

LG: You said people didn’t understand them? Or they just didn’t respond to them? They didn’t like the idea they were upside down?

RB: A few of my friends liked them, but in general, there was less response. Also, I happen to have had a series of dealers of different kinds who either retired, in one case died, got divorced, or moved back to Europe, I was afloat for a while then.

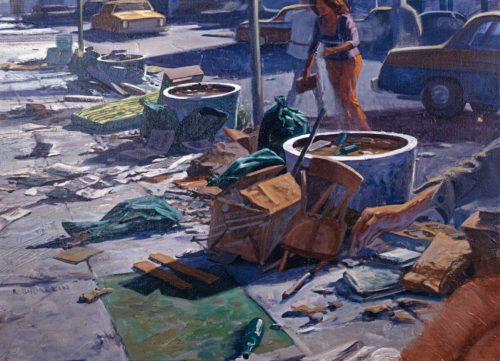

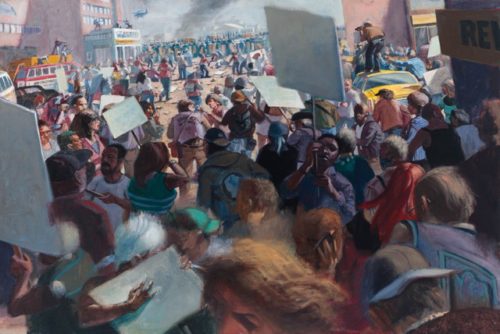

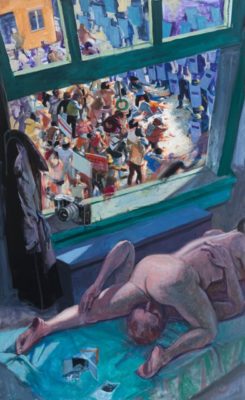

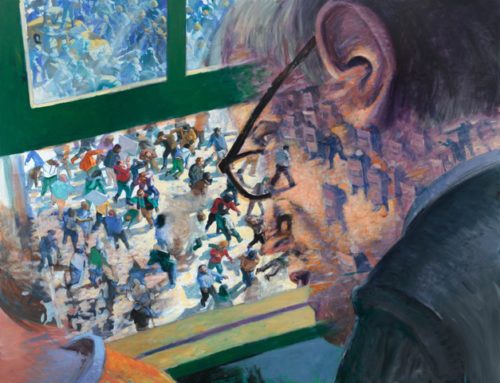

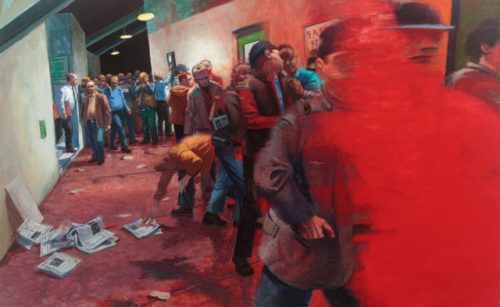

LG: How about the series of work that you did around the Occupy Wall Street Demonstrations. I’m curious. You could see the demonstrations out your studio window?

RB: From around 2010 – 2012, there began all of these uprisings in the Middle East the Balkans and elsewhere, as well as demonstrations here in this country

I began to kind of think about that, but think about it from my position and the position of people I knew. We were watching from afar. We were watchers, not actors. That became key to it.

I made a number of paintings of crowds, demonstrations and uprisings seen from afar. Sometimes there was a fragment of a figure seen within the room, sometimes a photographer looking out. I was thinking about my own situation, and people I knew, their positions of separateness and privilege from these events–which were tearing apart other people’s lives. Even those events, which might be happening outside your window.

When Occupied Wall Street happened, I went down there several times to make sketches. I could use them as drawings but not as paintings, I couldn’t use them that directly. But, they sort of melded into the larger theme. As the drawings and paintings accumulated they began to suggest a narrative. The paintings began to fall in narrative sequences, not because I was planning it so much, but it just was naturally so. The crowd gathers. The crowd moves. The crowd encounters the power of the state one way or another. There’s tear gas. There’s some firing. Someone has fallen. The crowd surges back. The crowd retreats, leaving someone behind. The street is cleared by the military or police.

I sort of was playing that through, thinking of Egypt. Thinking of Libya. Thinking of the Wall Street, though that didn’t come to gunfire. Thinking about the racial problems that had plagued our country for a long time.

The watcher. Who’s the watcher? The watcher, sometimes it’s just an arm. The watcher is you and I. The watcher is so many of us.

This is not agitprop art. It’s seen from a certain vantage point. Then, what was happening with these revolutions, in the Middle East, particularly, begun by idealistic democratically oriented young people, the way they turned into such, often, ugly things. There was betrayal within them. That’s ended, in most cases, with some kind of authoritarian government.

Then, trying to think about finding a form, finding the symbols, to suggest the change of the crowd from one state into another, into its own enemy.

A Walk in the City, Video showing Drawings by Robert Birmelin

I have hundreds of drawings. I have several big paintings, and mostly small ones. Those went from maybe 2012 to 2016, Then, in 2014 things happened in my family that have changed our lives, I was seldom in the studio or able to paint for a long time.

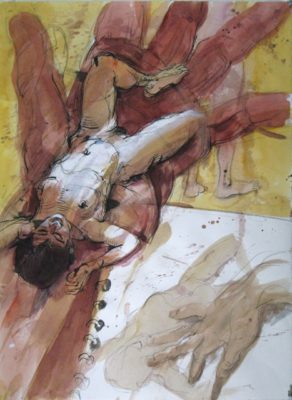

RB: When I came back, it was different. I really haven’t been working on canvas or paintings, but I work on drawings and mixed media with color. I’ve done several series of works on paper. One is called Physical Contact. It’s really about sex. There’s also a series called Legs on 8th Avenue, which kind of pick up on the urban theme, in a different way.

There’s a whole series that I’m working on now, of fantastical landscapes, which was triggered by seeing an exhibition at the Met. of Hercules Seghers, a 17th century Dutch artist who I’ve always been very interested in. He has these peculiar etchings, which were often partly painted. He never saw the Alps as he lived in the Netherlands. But, he painted mountains. Often the mountains almost looked like the convoluted forms of a brain, oddly evoking both identifications.

LG: Some of today’s aspiring realist painters are very concerned with learning technique and compositional strategies as the best path to making great art. They often equate success with the level of detail and photographic exactitude. On the other hand trends in today’s art world can often seem to encourage the notion that skill is irrelevant and the idea is what is important. The wall text becomes more important than the artwork. Care to weigh in on this dilemma?

Skill is never irrelevant. There’s a lot of figurative painting that I don’t like at all. I don’t like this sort of licked over painting that just terrible to stinks of its photographic source.

I don’t use photographs; I prefer to generate stuff from drawing, and imagination… I always have. That seems like more fun. But, I know a lot of people who do use photographic sources, and some use this with profit. But, when your first reaction to a work is to think, “Gee, it looks just like a photographic. Look how detailed it is” That’s vulgar.

As I said earlier on, I’m a partisan, you know? In my heart of hearts, I think that you should either look at it or make it up. But, I recognize the world is bigger than my own individual belief.

RB: How to free the final product from its source, to embody rather than just illustrate the ones experience, that is the question, is the great challenge.

I want the painting to be a free zone that is continually open to discovery and change. That, for me, precludes the dependence on an exterior image, photographic image.

On the other hand, for instance, I respect Chuck Close’s work, he makes very interesting paintings. But, he’s very conscious of what he’s doing with the photographic image. He’s an abstract painter, who works with a certain source and transforms it at a certain distance. It’s an optical game. There is no predicting, what method an artist may employ to come up with remarkable, innovative work. I’m wedded to my own methods but recognize the infinite variability of artistic creation.

LG: That’s good. Sounds like a much healthier outlook.

RB: Everything is going on all the time. Usually, each of us, in our little cocoon, only sees a little section The beautiful, the horrible and everything in between is going on all of the time.. How to be true to your own experience is the adventure of being an artist

A wonderful and in-depth article about a serious and important artist (who also was a great teacher of mine). Thank you Larry for asking such great questions and Bob, for your honest and interesting answers.

I remember how exciting it was to discover Robert Birmelin’s paintings in the 1980s’! The motion and energy and capturing the anxiety generated by the crowds moving in the streets – and the amazing ability to capture depth of field. I was painting in NYC at the time, having graduated from Cornell in 1974, and it felt invigorating to see strong, figurative, expressionistic painting.

Mr. Birmelin seems like such a nice man, it pains me a little to say this: His paintings strike me as over-sized illustrations. Kudos to him, though, for slamming all the projected, “it looks just like a photograph,” crap passing for painting these days. Kudos, also, to Josef Albers for being way ahead of his time in dissing all the runny, drippy paint that has become so prevalent in so much painting today. By the way, I exhibited a painting in the Prince Street’s juried show a few years ago. I called to discuss shipping arrangements and was told by the gallery person on the phone that they rarely sell paintings in their juried show. So be aware. With entry fee and shipping costs, it could run you well over a hundred dollars for the privilege of decorating their walls for a month. No thanks!

I see you aren’t going to publish my comment on Robert Birmelin. Why is that? Because I didn’t gush about or flatter the painter you decided to interview, but instead gave my honest opinion. Or was it because I honestly described my experience with the Prince Street Gallery’s juried exhibition? Either way, you need not worry again. Your blog was one of two that I followed. But I’ll be dropping yours as soon as I find the place where you can un-follow a blog. As somebody once said: “If you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen.”

I set up the comment system here to to prevent spam by me first approving the comment for the first comment made from an email account. When I’m away from my computer, first time posters have to wait. Once I’ve approved the comment from that email address – their future comments go through without my moderation. I very rarely censor anyone for what they say, no matter how much I might disagree with them. Unless your post is particularly abusive, mean-spirited or spammy I will likely publish it. Your tone made this one a tough choice but I decided to publish it anyway. I’m sure that isn’t the first time Robert Birmelin heard that take on his painting. The Prince Street gallery is correct to say that paintings don’t often get sold in the juried show – I would venture to guess that a depressingly small percentage of paintings get sold in most venues. We painters need tough skins and a strong love for painting and find ways to do it no matter what the difficulty.

Don’t quite get it since I’ve posted a couple of comments in the past on your blog. I do think as artists we owe it to ourselves to be honest without being cruel about it, unless the work is so shallow that it’s just asking for it. I will say I like Mr. Birmelin’s drawings. There is something more direct about them and therefore they have a charm lacking in the paintings. The comment on Prince Street was merely meant as a heads-up for any struggling artists who might think New York means an automatic sale. By the way, I’ve read comments by famous artists that completely eviscerate other artists, including highly regarded ones. And by famous, I mean Picasso, Gauguin, Freud, etc. Maybe I jumped the gun. I’ll hang onto the blog. I do find it interesting to read what artists have to say about their work, but not for the reason you might think. The poet, Apollinaire once said, “One should apologize first before talking about painting.”

Larry thank you so much for this great interview with Robert Birmelin. So many wonderful paintings that I have not seen before. Really taken with his imagery – a powerful representation of our contemporary life and social issues. Mention of Edwin Dickenson brought back sweet memories of Francis Cunningham talking about Dickenson in my classes with him. That system of patches!!! Moved by his philosophy “How to be true to your own experience is the adventure of being an artist”

Many thanks to you both.

Thank you for such a fine interview. It is my first insight into Robert Bermelin’s history, as he is my great uncle; my grandmother’s brother. I met him in the early 1980s after graduating from the fine arts department at Parson’s School of Design. A visit was arranged by my father, RBs nephew. He looked at my artwork with not a word and seemed wholly disinterested. I was naive and “green” not knowing what to expect. All I knew was he was an established and respected artist. I can understand that. It takes a kind of person to live the life of a painter and you sacrifice a lot. A choice you make early on. I could relate to that choice, one I did not wholeheartedly make, and had many painter friends (still do) who carry that torch. It is a long slog. It was great to see the range of paintings in relation to the artists timeline, travels, ups, and downs. I have my opinions about the artist’s output, but they are dwarfed by the success and a life well-lived making art. Thanks again for the look inside.

My parents were at the American Academic with Mr Birmelin in 1961-1963 and bought one of his paintings, which my mom thinks is called Interior/Exterior–We grew up with that painting on our living room walls as well as one by Mr Chaet. My mom has Birmelin’s painting and I have Chaet’s. Fascinating to see how the multiple perspectives of that piece are carried through into so much of his subsequent work. These pieces were very formative for my sisters and me.