I am delighted to share this email interview with New York City-based painter Paula Heisen. My interest with Heisen’s art began upon discovering her work on Facebook and was further enriched by a visit to her Long Island City studio a few years back.

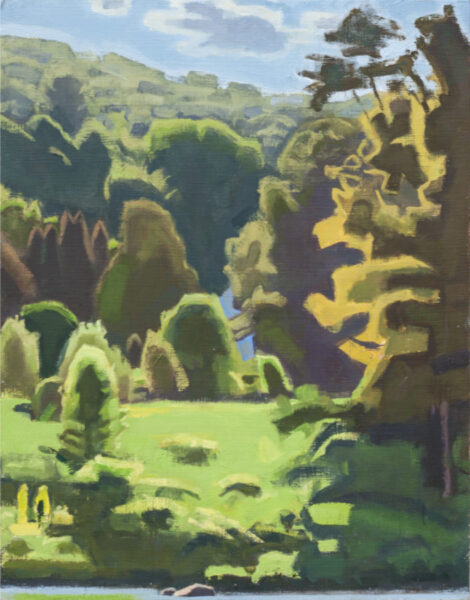

The emotional resonance of her nature-inspired landscape and still life compositions, coupled with the richness and precision of her color palette, left a lasting impression on me. Her work demonstrates exceptional spatial clarity and a delicate mastery of paint application. Heisen’s artistry transforms everyday scenes into lyrical expressions that evoke the spirit of early modern landscape artists like Charles Burchfield.

In this conversation, Paula Heisen delves into her background, her approach to painting, and her perspectives on working from observation. I am deeply grateful for her willingness to share her time and insights for this interview.

Paula Heisen is a graduate of the Yale School of Art MFA program. Her art has been featured in solo exhibitions in New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas. Heisen’s artistic excellence has been recognized with several grants and awards, including an Elizabeth Foundation Grant, a New York Foundation for the Arts grant, a Joan Mitchell Emergency Grant, and an Ingram Merrill Foundation Grant. Additionally, she has received scholarships to Yale, the Skowhegan School, the New York Studio School, and the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Heisen’s commitment to the arts extends to her role as an educator. She has taught at various prestigious institutions, including the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York City, Lehman College in the Bronx, NY, the Oxbow Summer Program in Michigan, Yale University’s Summer Program in New Haven, CT, and the University of California at Santa Barbara.

See more at PaulaHeisen.com.

Larry Groff: Can you recall your earliest memory related to drawing and painting? Were there any specific experiences or influences in your early life that ignited your passion for painting?

Paula Heisen: The earliest thing I remember is not about painting or drawing, but making a snake with Play-doh. I felt the magic of creating something out of inert material and how it became alive. Powerful sensation.

LG: Did you have a particular professor or mentor at Yale who made a significant impact on your artistic development?

Paula Heisen: For undergraduate work, I went to the College of Creative Studies, an independent program within UC Santa Barbara. This small school was for advanced, self-motivated students in the arts and sciences. Many of the students came from the East Coast – they were fast-talking and intense, which is probably why I became interested in coming East. Various artists came through to teach a semester or give lectures. Hank Pitcher was the teacher closest to my sensibility. He painted the local landscape, which he had grown up and surfed in. I think that his relationship to the landscape has always been in the back of my mind. Considering the state of the art world in the 70s in the U.S., landscape painting was both retro and brave. I learned a lot about how to think about color from him – both in classes and in seeing his work. He introduced me to the work of Fairfield Porter, whose work influenced me a lot. He admired Paul Georges and brought him out to the school. I remember being struck by his narrative paintings. In the regular art department, I took some drawing classes with Howard Warshaw. I discovered that my ideas about drawing were limited – he taught me to draw and think in three dimensions.

The most important teacher for me there was Keisho Okayama, who was a guest instructor in my senior year. He was very intense and embodied the connection between one’s emotional life and art. I remained friends with him after college until his death in 2018. I admire his work, though our interests differ. He saw and painted an internalized, mystical light, while I am obsessed with how light sculpts and defines form.

At Yale, Natalie Charkow, Andrew Forge and William Bailey were important professors. I took sculpture with Charkow, and her direct way of talking about and critiquing art was both exciting and grounded. She was one of the few women teaching there then, and her presence was important to the female students. I was Andrew Forge’s teaching assistant in my second year, and that was an education in itself. A beginning drawing class for undergraduates, every class was an intellectual journey and revelation. I internalized so much about the way he thought about art – about the relationship between thinking, seeing, and doing, how complicated and wonderful it is. I also became friends with Forge’s wife, Ruth Miller, while at Yale. Her luminous presence and painting have shown me how to combine a womanly spirit with deep intelligence and devotion to art. Bill Bailey was brilliant in a particular way, as his paintings are. He had a wickedly good eye, and I learned so much hearing him talk me through a painting – whether it was my own or another student’s. Both Forge and Bailey revealed the magic of what painting could be. Bailey always said that every painting is abstract. It didn’t matter whether you painted representationally or non-representationally, from life or your imagination. What mattered was that a painting lived an independent life – that it became more than a sum of its parts.

Through my teaching and study, I realized that an interesting painting has a certain balance of unity and contrast. Style is unimportant in this equation since that balance can be achieved in many different ways. For years, I described paintings that reached this level of accomplishment as “perpetual motion machines for the mind.” That doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue, so I reduced it to “mechanism” or “contraption”. Reading a book of essays, Observation: Notation, by Andrew Forge, I came across this quote in an essay about Giacometti: “The achievement of the Forties and Fifties is unthinkable without the Surrealist experience at the back of it – without the notion, that is, of the work of art as an infernal machine.” Infernal mechanism is about right.

LG: How much did Yale’s network and reputation help you in your transition from student to professional artist?

Paula Heisen: Yale was a mixed bag. It did help with grants, short-term teaching gigs, and some shows. But I didn’t want to teach full-time. I enjoy it, but I find institutional situations difficult to tolerate. So, I never used the degree to advance myself in that direction. The best thing about it was the serious artists who were my fellow students. I learned a lot from them.

LG: Can you share a specific early success or breakthrough that was particularly meaningful to you?

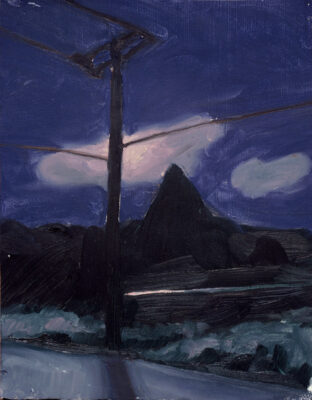

Paula Heisen: In the summer of 1977, I went to Skowhegan, which was life-changing in many ways. It was a year after I’d graduated from college. I spent that year heading up the advertising graphic design section of a local newspaper. I was lost in terms of painting – I did paint, but my efforts had no cohesion. I was excited to have two months to just paint with no distractions. Food prepared for us, studio provided. I shared a studio out in a cow pasture with a few other artists. They mostly painted in the landscape, and I had this great isolated space to myself. I wasn’t ready for the East Coast landscape, though. The greens seemed to be all the same. Coming from California, with such a wide variety of greens and with hills that were golden in the summer, it was a bit of a shock. I started to paint night paintings to avoid the whole issue, working from sketches. I developed a body of work there, the first time I’d done that.

Then I got a scholarship from Skowhegan to the NY Studio School – it was the first time I lived in New York City. That was a difficult year, I had no money, no winter clothes–can’t say I’d thought things out very carefully! I stayed for a year in New York, went back to Los Angeles for a few years, then to Yale, and finally back to New York City again. It had gotten into my blood.

LG: As I understand it, for some time now, you’ve been dividing your time between being in the Catskills making landscape drawings and the still-life paintings you make in your studio in Long Island City. Can you tell us a little about how you arrived at this workflow?

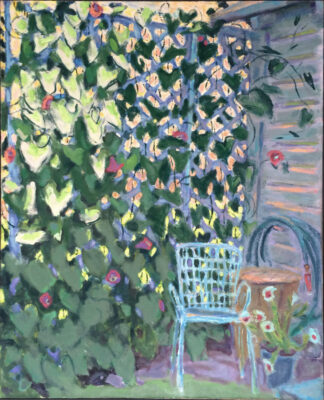

Paula Heisen: I started to work mostly from the still life when I returned to the city in 1982. Trying to deal with the weather and working freelance jobs made landscape painting impossible. My first apartment overlooked Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn. It faced south, and I used the living room as a studio. It was filled with warm southern light, which I like. I was also doing narrative figure compositions. I was there for four years and eventually stopped doing the figure work. The interest was just not there anymore. Looking back, I think those paintings were dreadful! I need the energy that comes from looking at something interesting or emotionally engaging. I met my future husband in 1985 and later moved into his apt, using the extra bedroom as a studio. It was a lot smaller and had north light. The paintings completely changed, they got darker and thicker and more abstract. I continued with these still lifes for a few years until we bought a small house upstate in the town of Lexington, NY. For some reason, I became passionate about gardening – and I started to paint the landscape again. I use an old garage as my studio there, and for years, I had a graphic job that allowed me to take the summers off. Although I’d created the garden to paint from, I couldn’t look at it without thinking of weeds, and I returned to still life painting to escape the outdoors…

Around 1998, I started my own graphic design business from home – which meant I no longer had summers off and still life painting was again my modus operandi. I rented a studio in the city for the first time outside of our apartment – and have cycled through many spaces since then. Still lifes continued to be my dominant subject in my NYC studios. I collected lots of objects and used them to create narratives. This was really fun, and I always despaired that I had too many ideas and not enough time to paint. I started to

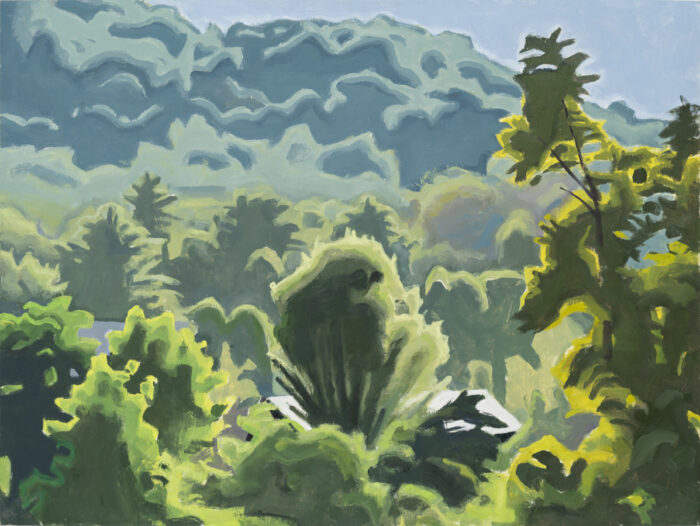

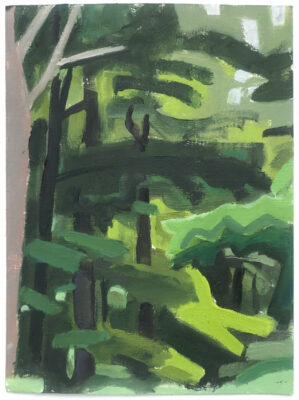

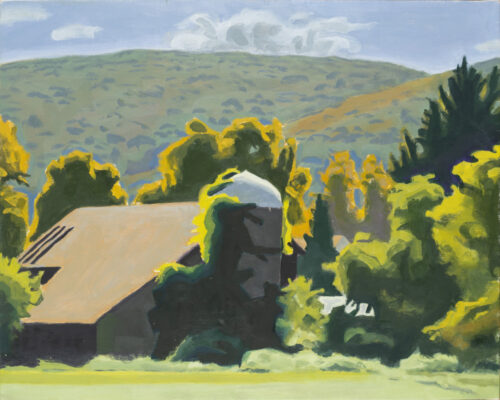

do small landscapes upstate again in 2010. I have a powerful feeling for this Catskill landscape – I feel overtaken by it. I’m not sure I’ve reconciled the landscape work I do with my paintings in my current studio in Long Island City. I feel guilty about the two bodies of work not being connected enough. But they both satisfy something essential. Recently, the still lifes have taken a turn, with only the fabric remaining in the set-ups. This has opened up an exciting new path.

LG: In both your landscapes and still lives, you find ways to limit your views in order to concentrate on certain aspects of your motif and subject matter. I’m curious if you can talk about what ways you see your landscapes and still lives are going after similar things.

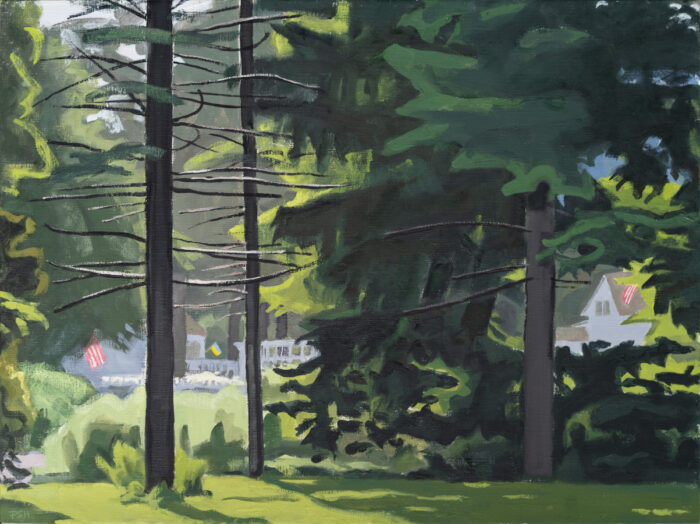

Paula Heisen: I can’t say whether they are going after similar things – maybe I’m too close to them, but the experience of working in each mode feels quite different. For one, I usually look for some type of deep space in the landscapes. Even if I have a large area of darkened foliage taking up a lot of space, I will be able to escape somewhere into deeper space. The still lifes have a much shallower space and are more intimate. The experience of painting them is not as encompassing as being outside, where there are countless elements to contend with – the weather, the heat, the wind, the insects, etc. All those things, even when annoying, add to the intensity of painting outdoors and are part of the reason I love it. I feel alive. I am calmer working from the still life. I can control the light better, I don’t have to deal with the weather, I can luxuriate in what I’m looking at. The still lifes are more introspective – and colors other than GREEN can be used. There are commonalities. I always think about atmospheric perspective – I just use it differently when painting from a set-up. Mostly I feel the two endeavors are distinct in intention and execution.

LG: Your landscapes seem to respect the specific qualities of a place and are carefully observed but you also bring an expressive, lyrical simplicity that avoids being too literal. What are the most important aspects for you in this painterly approach?

Paula Heisen: This question kind of answers itself. I do love to draw, to capture the sensation of an object in space. But I don’t want to be slavish, to render every little thing. Some painters can do that; it makes sense with their sensibilities. I’ve developed a sort of individual shorthand over the years. The trick is not to let it become schematic, which I consider a non-thinking way of painting. I always want to be responding to what I see or a memory of what I see. When you look closely at things, there is so much there; it’s always fascinating. Especially trees and shrubs, I have never seen a boring shape or line in a tree! Fractal growth.

LG: Can you say something about getting simplicity from the chaos of nature?

Paula Heisen: The simplicity comes from the initial emotional response to a motif. I try to hold on to that throughout the long process of making a painting, distilling it and deleting any extraneous elements in the work.

LG: Would you say that your landscapes reflect your inner thoughts or philosophy in some way? If so please explain.

Paula Heisen: I would say that instead of thoughts or philosophy, I have an emotional kinship with the spaces I paint in Lexington. And with how the light falls on what I’m looking at. Every year I feel more embedded in the landscape. Recently, I watched a Swedish TV police procedural called Jordskott, in which a side plot involved the child of the head detective. He was slowly being transformed into plant matter. In the last episode, he is swallowed by the earth. I’m afraid I feel like that at times! I suppose it’s a paganistic/pantheistic mental space – everything is alive.

LG: Charles Burchfield, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, the Canadian Group of Seven, and similarly landscape-focused early modern abstract painters would seem to have inspired you to some degree. What painting concerns might you have that these landscape painters might have also had?

Paula Heisen: When it comes to landscape painting, my heroes are Fairfield Porter, Marsden Hartley and Charles Burchfield. Porter for his subtle and beautiful palette and for the flat shapes in his paintings. I looked at him a lot earlier in my career. I feel Hartley’s ties to the landscape he loved, and he was able to come up with a painting language that was simple and potent – I especially love the later paintings. Burchfield is an interesting case! Sometimes the drawing tends toward the illustrative, but he usually pulls it off with his use of color and light. The Burchfield Penney Center posts a painting a day on Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/burchfieldpenney/), with an excerpt from his writing. I love it. He’s a great writer, and you get a sense of how much he loved looking at and walking through the countryside.

LG: Can you describe a moment when a particular landscape grabbed you, and you knew you had to paint it? What was the emotional connection?

Paula Heisen: At the beginning of the season and throughout the summer, as the light changes, I walk the circuit in my Catskill neighborhood. I try not to impose anything on what I’m looking at, just try to be receptive – almost in a trance-like state. There’s no rhyme or reason, though I have several motifs that I return to. Usually, it happens when I’m not thinking at all; turn my head, and bam. It’s about being able to be surprised by well-known surroundings.

LG: I was watching a video talk about the Van Gogh Cypresses exhibition at the Met. I’m curious if you’ve seen this show and if you might share your thoughts about this show. I’m particularly interested in how Van Gogh’s expressive, stylistically swirling linear strokes for the cypresses, sky, hills, etc. hold up for you today after years of being on tote bags, coffee mugs, and dorm room walls. Or does the power of his vision and painting chops transcend all the art world hoopla? Can today’s landscape artists painting similarly still be taken seriously?

Paula Heisen: Terrible to say – I missed that show! I came to the city for dental appointments and went right back upstate. It has been a rough summer, with so much rain, and I had to be there when the sun was out.

I love the cypress paintings. I am never put off by all the merch in relation to painters. It’s just silly stuff, and sometimes I buy it as a joke. But a great painting is a great painting, and seeing it in person is always an incredible experience. I saw the Munch show at the Clark Art Institute, Trembling Earth, last summer. I thought about van Gogh, and felt Munch had the same intense bond with the landscape. But van Gogh was a more exacting painter in every way: composition, scale, drawing, color. I have immense respect for him.

In terms of “painting in a similar manner” – I don’t think anything is off-limits in terms of inspiration. That’s one great thing about the crazy time we are living in right now. People are free to follow what interests them. It doesn’t matter what someone paints, but it has to have an emotional core.

LG: In some of your landscape drawings, the inventive ways of organizing the tones and marks remind me a little of Van Gogh’s later drawings. Do you consider your drawing studies or stand-alone drawings for their own sake? What can you tell us about how you go about drawing the landscape?

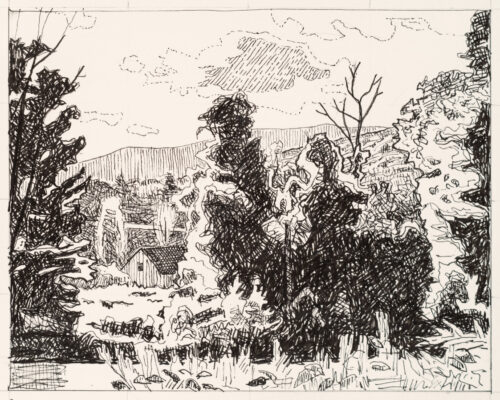

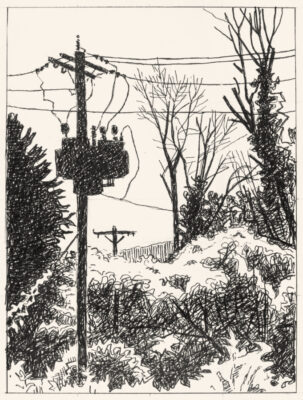

Paula Heisen: I mentioned my motif hunting earlier…I photograph the things I’m struck by, and organize the images by time of day and weather. I let them sit. Usually, there are a few that I know I want to do, and I will look at the photos to see if I’m right. That’s the first step. The drawings are a way to organize my thoughts. I think of them as studies, but they are satisfying as stand-alone pieces. I’ve started sitting on a stool because that gets me to the sight-line I will have when I stand to paint. I sketch first in pencil and then start with a nearly spent Pigma Graphic pen and move on to a newer, darker pen. I have a lot of these pens, and they only last one or two drawings before they get too dark or run out of ink. I used to do these painstaking ink washes. I layered light washes, gradually moving to the darks as I worked. I loved doing them, very calming. I did a lot of them the year after 9/11 – helpful in terms of my mental health. I think of the pen drawings in the same way, going from light to dark, bit by bit.

LG: You often have views of back-lit scenes, and the play of light and shadow takes on great importance. Sunlight changes very quickly, and dealing with such a complex subject with the clock ticking is quite the challenge. Please tell us something about how you go about capturing the feel of natural light with your color choices and compositional decisions.

Paula Heisen: Many of my images are backlit – that’s when the personality of the tree or shrub pops out like a star on a stage, with their arms out, belting a song.

In terms of the changing light – often, the moment I’m interested in does not last very long. It remains in my mind, but you must go with the flow. I usually paint for about 3 hours, and things change a lot in that time. I find that I like the way the sun hits different parts of a motif at different times, so every painting is a collection of moments. Whatever makes sense with the painting.

Color – it’s a complicated subject! The best way to describe how I think about it is the Munsell Color Solid, which is a sort of 3-dimensional color wheel, with colors moving from dark to light vertically and hues arranged around the central spine that move from desaturation to full saturation horizontally. It’s the concept of this that interests me, not his particular pigments. I have a simple double-primary palette, with warm and cool versions of each primary. I also use cadmium green because it does something no mixed green could do. I rarely use it straight, but it’s handy. Black, yellow ochre, white. I’m always thinking about where a particular color might be regarding value and hue on my internalized Color Solid. This palette is versatile enough to get me whatever I want or need.

LG: Do you decide on your main color scheme or harmony and mix accordingly before painting or mix your colors as the painting progresses?

Paula Heisen: I do small color studies for each painting, which are the same size as the drawings, about 7 x 9 inches. Then, I mix the palette from the color study. Usually, it takes a few hours to do that. I will also have a sketch on the canvas before I go out to paint with the full palette. This helps me to relax, since the changing light and all the other distracting things about landscape painting are crazy-making. I want to have fun out there and feel free with the mark-making. Having the color worked out helps with that. Of course, a lot of improvisation still goes on.

LG: How do you see shadows as more than just a visual tool, but as a narrative or symbolic element within your still lives? Can you describe a specific piece where shadows played a crucial role in the overall composition and meaning?

Paula Heisen: Shadows are really important to me! I watched endless film noir movies when I was a kid. I loved them. Black and white, simple shapes – deep space and foreground in conversation. You’re able to do so much with that!

A lot of my still lifes in the last few years have shadows larger than the lit objects, and I consciously want a sense of something looming. In Darkness Above, this was the prominent way I thought about the setup. It was after a year and a half of Covid, and I felt all the disorientation and fear of that time. A few years ago, I titled a painting Doppelganger. That conveys the metaphorical sense I have about shadows: they are ghosts, twins, memories, traces… Of course, where there’s a shadow, there is glorious light, gilding objects with gold or moonshine.

LG: In your approach to still-life painting, you’ve eloquently stated in your Zeuxis interview “Conversations with Paula Heisen, Sydney Licht and Rachel Youens”, restricting your setups to just a few elements, such as a flower, patterned drapery, and shadows, you paradoxically expand what you can do. This notion of simplicity leading to complexity is both intriguing and counterintuitive. Could you elaborate on this philosophy and explain how this approach informs your creative process? If you can, maybe you could point to a specific example.

Paula Heisen: The progression of my still life imagery is strange even to me. Originally I was excited with the idea of the objects infused with some narrative, either a personal one, or one based on world events. Often, a change of place has caused a change in imagery, and when I moved to my studio in Long Island City from Brooklyn, I lost interest in the narratives. I struggled for about a year before concentrating on the patterned fabrics and flowers – an endless source of exciting ideas. As with film noir, I have a childhood love of fabrics. When I was 5, I hypnotized myself by looking at the women’s dresses in the pews in front of me to relieve the boredom of Mass. This was in the 50s, and there were a lot of colorful patterns. I learned to sew when I was older, and the fabric aisles were heaven. I wanted pieces of them all! When I started using fabric more in my still lifes, I relived that experience. Eventually, I moved away from the tabletop as a structure for the paintings. It may seem that just having fabric and flower is reductive, but it opened up the space in an interesting way. There’s an openness and a floating sensation that I’m moving toward now. It seems more related to the landscapes.

LG: Our art world today is filled with a cacophony of styles, mindsets, and an ever-growing emphasis on digital and conceptual mediums; traditional observational painting can sometimes seem overshadowed or even anachronistic. I like to hear about how other painters cope and navigate this terrain that often could care less about tradition and beautifully made paintings. Will traditional painting ever finally stay put on its ‘deathbed’ or do you believe that it holds a unique and irreplaceable value that continues to resonate with audiences today?

Paula Heisen: Like sex, I think painting will always be around! We need it. Is something dead when people want to do it? When there is a community of like-minded artists who share the same interests and obsessions?

In 2019, we went to two caves in France with prehistoric paintings: Peche Merle and Niaux. It was awe-inspiring – the power and the energy of the drawings are still vital today. Seeing that, who wouldn’t want to do something like it?!

There’s a freedom today that I alluded to earlier. People can do anything, think anything, when it comes to “art.” I don’t begrudge anyone whatever direction they take, even though I might not be personally interested. I like being closely connected to the rich tradition and history of Western painting and enjoying the intelligence of artists working in different times and places.

LG: Can you talk about your experiences navigating the dichotomy between making good paintings and the demands of promoting your work? How do you stay focused on your artistic vision and maintain your passion for painting amidst the complexities of the New York City art market? Has this dynamic influenced or changed your approach to your work in any way?

Paula Heisen: I found it nearly impossible to finish this interview while painting this summer. It interfered with my absorption in the landscape. That’s the problem with using language for a non-verbal activity – it takes you away from the essence of the work, as your question implies. I’m sure we all feel that. Speaking of doppelgangers, right now, I’m reading Doppelganger by Naomi Klein (not Naomi Wolf!) A major theme is how the presentation of the self on, say, social media creates a ghost self. And how that ghost self takes on its energy and trajectory. I’ve been pretty active on Facebook and Instagram and have certainly felt that happening. But when you have a show, you must let that devil in the room. You go into salesperson mode and face the attendant vulnerabilities and indignities. Perhaps because I’m older, it doesn’t affect me as much as it used to. We are bound by the conventions available to us and have to navigate between their demands and our deepest needs.

A very clear, intelligent and well written interview. I like the work very much, esp the small recent oil sketches and the pen drawings. Great color and interesting talk on the limited palette. Reminds me a bit of Welliver’s work with a very limited palette. The mark language is intriguing; and the references to Burchfield. And Porter. It reminds me that one secret of landscape painting is to develop a mark language as a way to paint the edges of trees and clouds, the color shapes. Very intelligent and beautiful work…I don’t think she discussed “beauty” at all, but her work is beautiful.

Excellent interview! I love Paula’s paintings and it was interesting to see her early work and read her thoughts on painting. She’s one of the best.

I enjoyed this interview. Thanks to both of you. There is a remarkable amount of freedom now to paint anything you want, anyway you want. I think the challenge to explain why you paint, what you paint, can take you away from your work, but it is a necessary task. It’s your only chance to remind people that you truly care about what you are doing and are deeply invested in it and not simply trying to sell a few paintings on instagram. And maybe some youngster who has never heard of Paul Georges will make a tiny effort and google him and learn something new.

an artistic, interesting, very American, journey, spreading from Milton Avery to Keith Haring … at times….

I notice that the lights of the paintings originate from the background, which isn’t something that I significantly remember is a motif other painters stick to. The way in which the forms are carved out give volume to the puffs of organic shapes. I find this memorable and unique, along with the color palette.