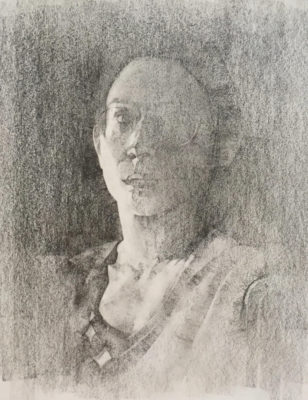

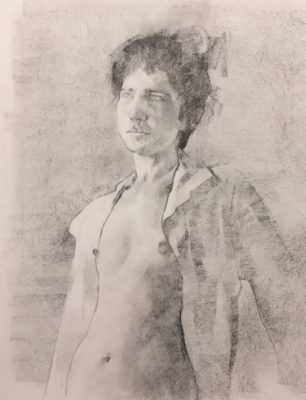

I was recently amazed by the brilliant paintings and drawings of Osnat Oliva, a young Israeli artist whose work I saw on Facebook. I was moved by how her paintings showed such a high level of intensity and dedication and asked her if I could show some of her work on Painting Perceptions along with me asking her a few questions. At first, she was reluctant, feeling that it was still too early in her painting career to be doing an interview. I was eventually able to persuade her to change her mind and would like to thank Osnat again for this email interview. Some of the original text was edited for clarity and grammar as English isn’t her native tongue. Osnat Oliva recently had an exhibition of her work this past August at the Jerusalem Theater gallery.

Larry Groff: Can you please tell us something about how you got your start with painting?

Osnat Oliva: I started my way into the art world with visual communication studies in a college in Jerusalem, where various courses introduced me to composition, shape, and line creative possibilities. The drawing class I took then wasn’t my favorite. It was my design course that started my exploration and love of composition.

After college, I worked several years as a graphic designer in an excellent firm in Jerusalem, but eventually, the work became mechanical and creatively frustrating. I took a drawing and painting course taught by Noa Simon at the Israel Museum. Her love of painting was contagious, and I decided to follow her suggestion to apply to the Jerusalem Studio School after a couple of years. I was captured by the magic and energy of the school when I first saw all the easels standing in a circle around the model stage with canvases decorated with juicy paint spots.

Quitting my job was a complicated decision. Fortunately, I had my parent’s support, and eventually, I studied for 5 years at the JSS. During my time there, Israel Hershberg didn’t formally teach but gave lectures and critics, which were fascinating and crucial for our understanding of painting. My teachers were Oleg Lissin, Nicole Ardilias, and Naor Ken-Dror. They were great teachers and very patient; each was unique in his own way. In my last year (and during all the summers in Italy), I studied with Didi Hershberg and Deborah Sebaoun, fabulous teachers and great artists.

LG: I’m curious to hear more about your study with the JSS. How would you say that shaped your outlook and approach to your paintings?

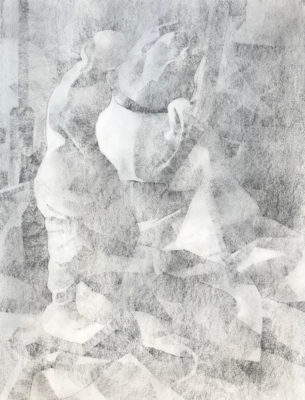

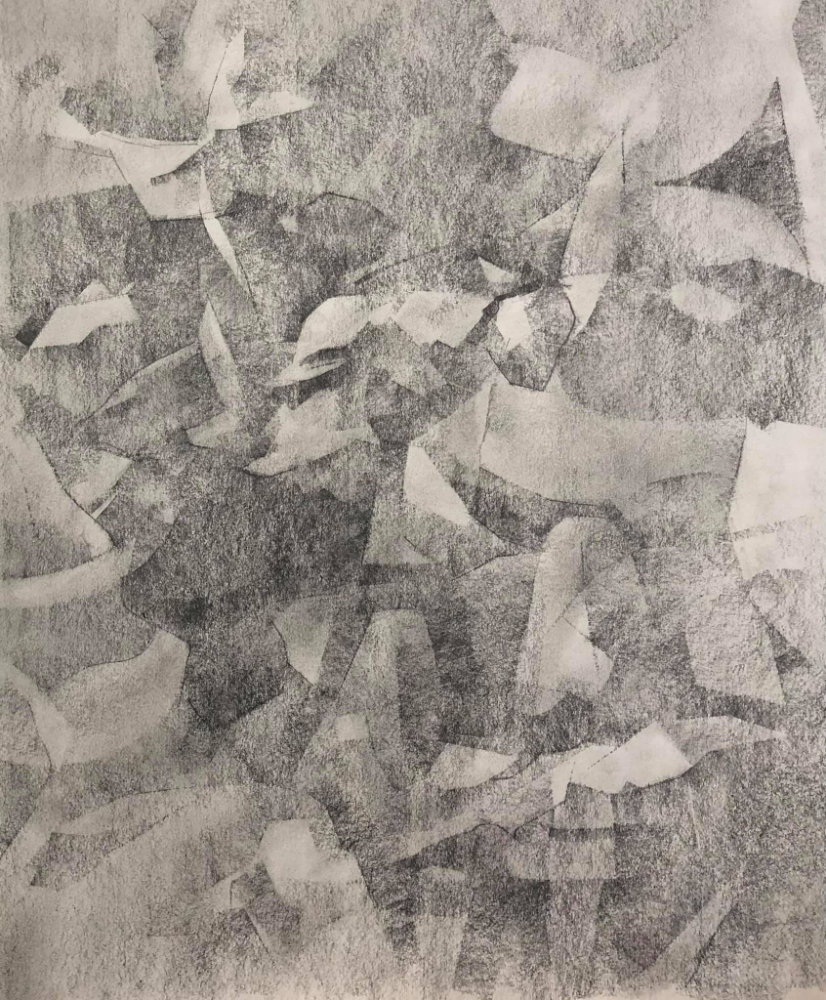

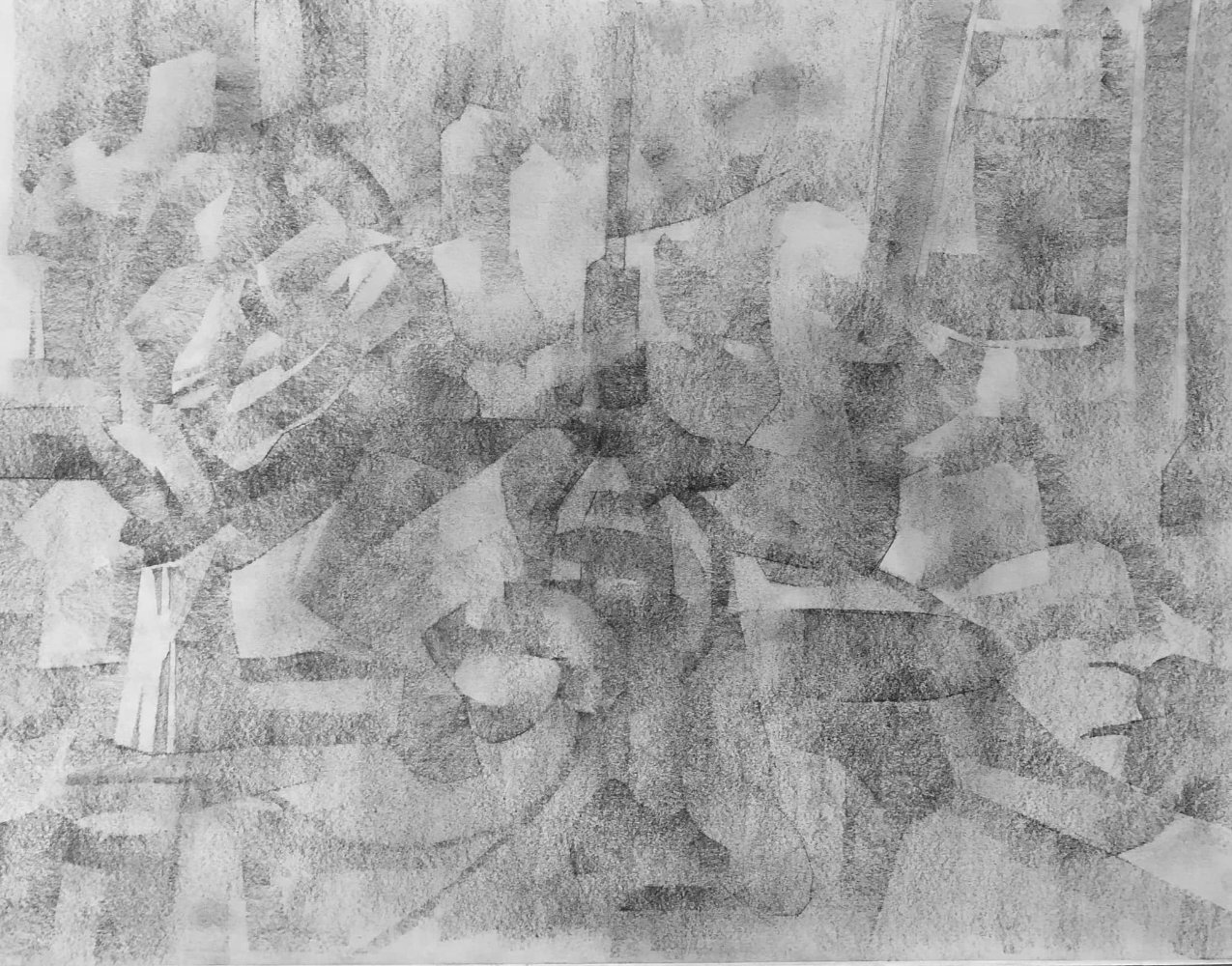

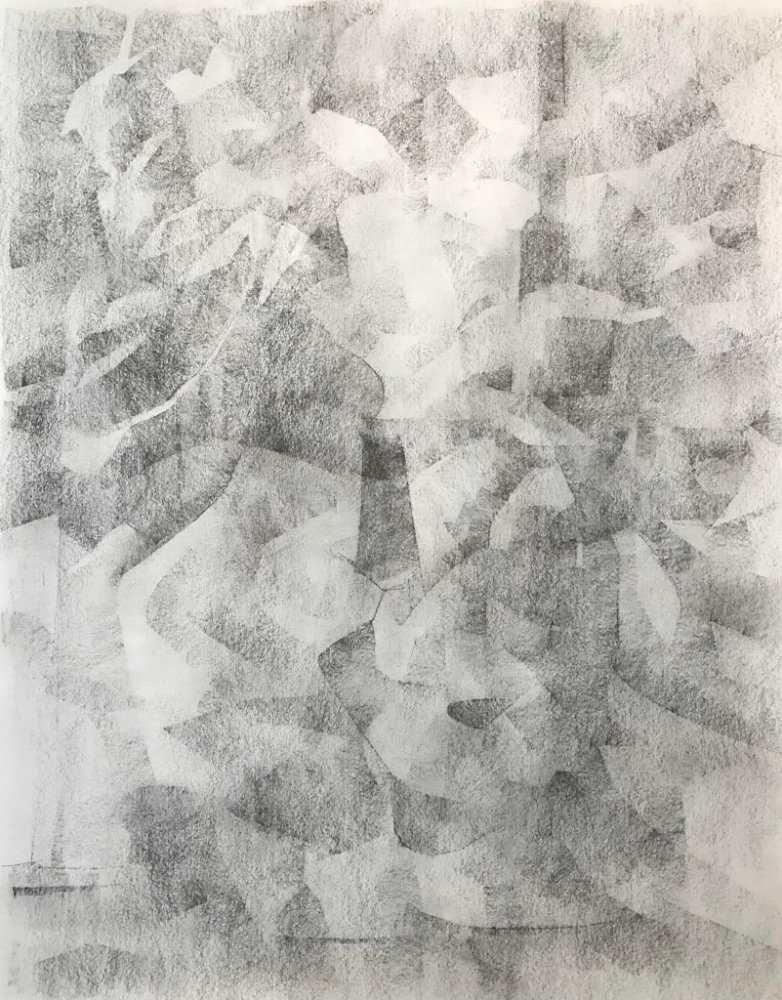

Osnat Oliva: The JSS taught me how the language of painting is abstract, describing forms abstractly with the tone, color, value, edge, and line. Eventually, my drawings started to develop more seriously by my third year. I then had my own studio to work on different projects alongside working from the model at the main class. I enjoyed drawing more than painting and preferred still lives over the model. Once a year, we had a “Junk-Pile” project that I enjoyed immensely. I was attracted to the abstraction of the fabric folds and describing the nameless shapes.

We had many lectures and critics during the school years with Israel Hershberg and Yael Scalia, and those lectures were essential for understanding the painting world and language. Israel used to show us slides of artworks and explained different aspects of painting and drawing. Those lectures sometimes felt even more important than actual practice; they were full of inspiration. In those years, I made an acquaintance with artists like Poussin, Titian, Corot, Ingres, and Edwin Dickinson. My list goes on and on, from early medieval painters like Giotto and early Italian painters like Piero Della Francesca to learn the more recent painters like Morandi or Lennart Anderson.

LG: What are some of your most important concerns with your work?

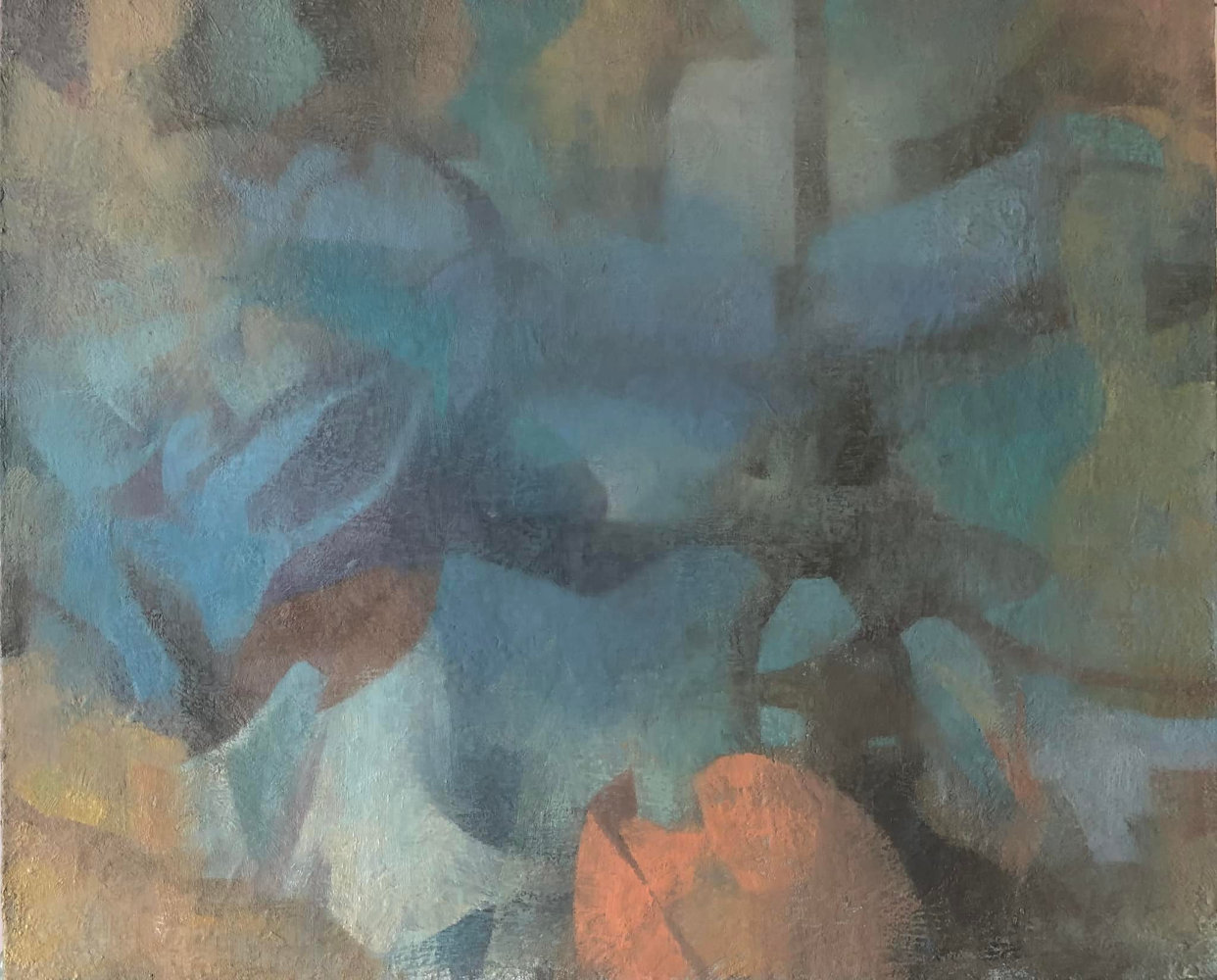

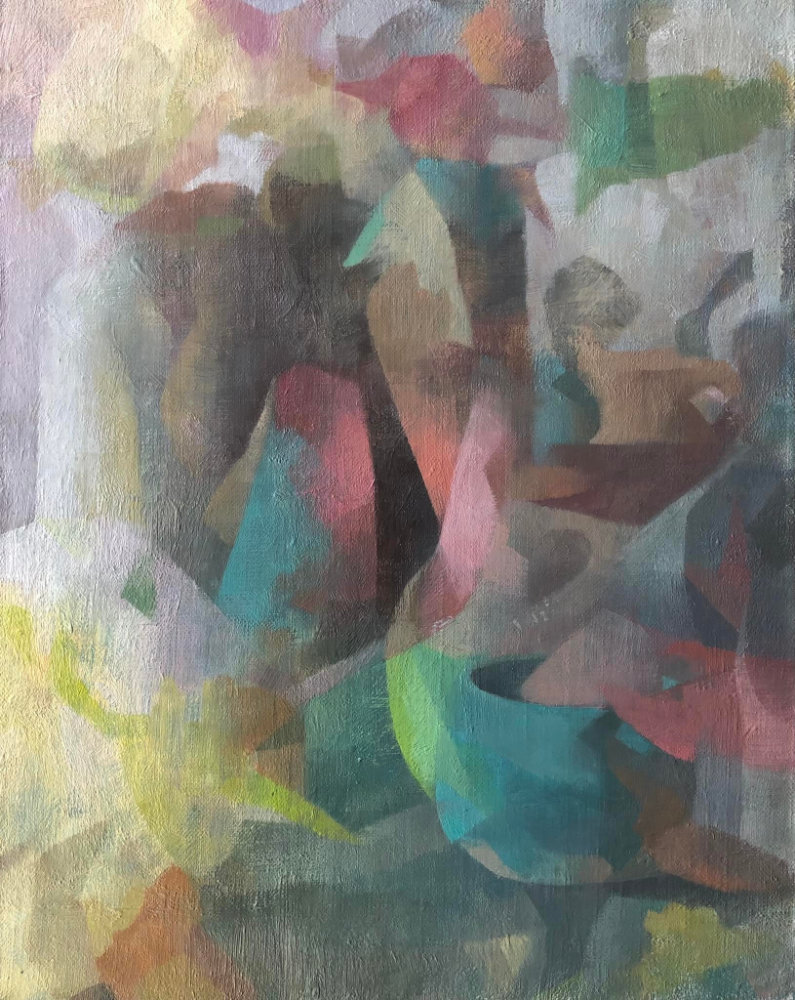

Osnat Oliva: After leaving school, I looked at the more modern painters like Matisse, Picasso, Klimt, Braque, and others. This opened another window in my mind to the endless possibilities in art. I think that’s why I gradually became more attracted to trying to paint more abstractly. I don’t want to neglect observation, like Picasso or Matisse because nature contains more variety and richer language than what my imagination alone can produce.

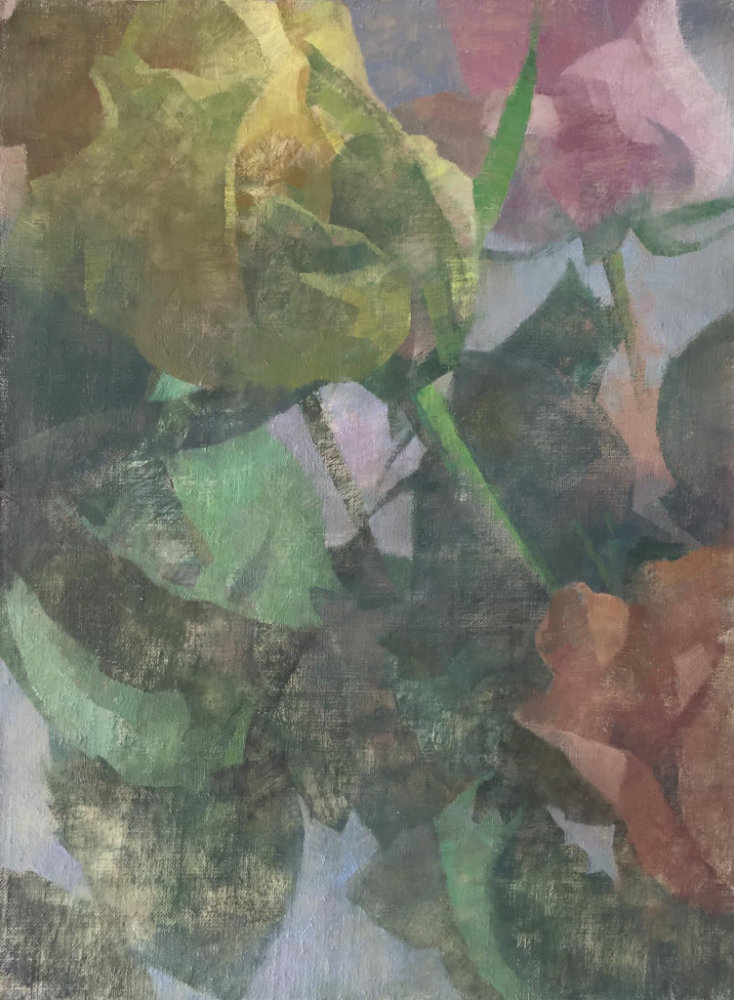

During the last few years, I realized I’m not as attracted to painting the figure or making portraits and have become more attracted to making still lives where I find abstract shapes and can compose with endless variations and possibilities. I tend to be attracted to busy compositions containing many shapes and movements over the simplified and sparsely populated ones.

I was always curious about how to use my still life tools’ shapes to create a more abstracted result. For example, I experimented briefly with zooming close up into flowers or rotating the angle of view to achieve a greater abstracted composition. More and more, I wanted to move away from realism and asked myself, “how and what did I want to paint?”

This took me on a journey of experiments where I went through a period loosening up my drawing to get a more open result, but this could weaken the compositional structure. I realized my drawing is a vital tool to use, not neglect. Instead, I started changing my brushwork, finding a way to draw with a brush similar to drawing with a pencil. Now I combine different working methods and focus more on the ‘what’ I want to paint. I’ve been inventing my own compositions. In some of the combinations, I even use parts of masterpieces from Poussin or Degas, and in others, I use only my own still lives motives. I play with it.

LG: What have been some of the biggest influences on your artmaking?

Osnat Oliva: My primary influence was studying with all the great teachers I talked about before. But another important influence has been Dorothy Mitchard, who has a unique way of observing and her enormous knowledge of art. She is the one that exposed me to the variety and endless possibilities in artmaking and to different painters. Of course, being exposed to master paintings in Italy and Europe greatly influenced me. Different artists influence me in different ways. For example, Edwin Dickinson has a unique perspective of describing simple motifs like a chair or a sculpture. His work taught me to search for the more surprising angle or inventive ways to describe the motif. The drawings of Poussin and Ingres challenge me to draw more sensitively. Susan Jane Walp helped me see the need to further push the arrangement of the still lifes set up beyond my first impulse. Yael Scalia inspires my efforts to be more sensitive with my brushwork. Edmond Praybe encourages me to embrace my love of painting busy still lives.

I see my own desires in other people’s work all the time. But eventually, it’s a reflection of my own attractions, wishes, and desires.

LG: Much of your work involves some form of study of masterworks; in what ways do you think this helps or hinders finding your own voice?

Osnat Oliva: During the third year at school, we copied many masterworks. In that way, you learn the work deeply, and through copying, you get a greater awareness of the artist’s decisions. Things you likely wouldn’t notice by only observing the work. Careful study of masterworks helps you unconsciously learn such things as compositional and color decisions, edges, and much more. This knowledge assimilates in your brain and helps you acquire skills, for example, to copy one of Dickinson’s premier coups work as a practice to achieve more spontaneous brushwork.

However, copying or studying masterworks to paint like them isn’t a good idea because your work will eventually look like a poor imitation of someone else’s work, and you’ll never find your own unique voice. That said, I still copy artworks sometimes. When I really love a specific work, that’s my way of connecting to it and embracing it to be part of my creation. For instance, I love Poussin enormously because of his beautiful drawing and movement. I see his work as a complex puzzle he somehow successfully composes into a unified whole, and I enjoy combining parts of his work into mine.

See more on Osnat Oliva’s website

or her Instagram page

Leave a Reply