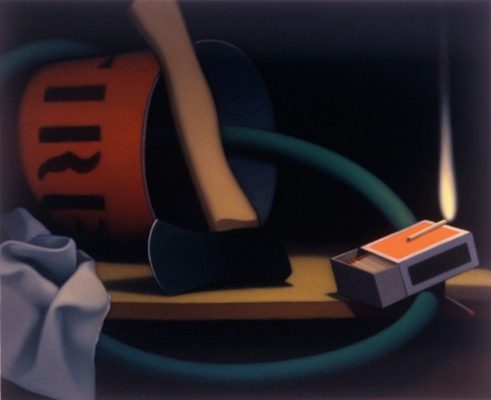

I’m very pleased to present this interview with the still-life painter Nancy Grimes who generously shares her rich experience as a painter as well as her thoughts on painting evolved from the years spent as an art writer and teacher. In particular, I wanted to learn more about her approach to merging “meaning” with the formal concerns of painting. Modernistic still-life paintings often recoil from suggestions of vanitas, politics, or preachy moralizing and rarely plays both sides in the perpetual battle between form and content. Grimes’ still-lifes challenges this edict with wit and sophisticated visual panache.

She stated on her website:

I’m different from other contemporary still-life painters because I’m interested in allegory, meaning, and reference. My still-life setups are very artificial and staged. I don’t go for the half-eaten orange on the breakfast table, the casual setup, or the delicate china cup next to a vase of flowers. I think paintings should have meaning that is challenging. The greatest painting is about human experience, and I think still life, even though it’s the most abstract of the figurative genres, the most resistant to interpretation, should also be about human experience.”

Grimes lived in New York City since 1980 up until two years ago when she and her husband moved to Chester County, PA. Grimes has shown her work both locally and nationally in numerous venues. She has written for Art in America and ARTnews. She has been an Adjunct Associate Professor in Fine Arts at the Pratt Institute since 2001 until she retired as a full professor in 2021.

Grimes wrote the monograph on the painter Jared French and one of only a few books on this painter, Jared French’s Myths

The Amazon description says the following: “Nancy Grimes’s illuminating essay offers an insightful analysis of French’s work and explores the influences that shaped his career, including his years spent with Paul Cadmus in Italy and his summers on Fire Island, and the influence of Carl Jung and William Butler Yeats on his work. Several drawings are included, as well as a major chronology and selected exhibition history, making this book the first complete reference source of French’s painting and career.”

Larry Groff: Please tell us something about your early years. What led you to want to become an artist?

Nancy Grimes: Like most children, I liked to draw. I enjoyed it but found it challenging. I remember an assignment in first grade. We were asked to draw a tree. I attacked the problem with gusto and drew a skinny vertical rectangle crowned with a starburst of spindly pencil lines. After I had finished, I realized that no one else had even started. They were waiting for instructions from the teacher, who demonstrated how to produce a credible tree with a few sweeping marks. Of course, I was mortified and the other kids taunted me, but when I look back on my hasty, clumsy effort, I think it revealed an interest in drawing—in figuring out how to recreate 3-dimensional form on a 2-dimensional surface—that fueled my pursuit of art and has never left me.

So, I had the interest and the inclination, but I was also lucky. My parents valued the arts even though they had very little money or education. They were avid readers and my father was an amateur musician who periodically played the drums in various jazz ensembles around Indianapolis, where I grew up. Both parents liked to sketch and had some talent. My mother decorated the house with fine art reproductions—the kind you could buy in museum shops for about a dollar at the time. I remember “The Sleeping Gypsy” by Rousseau and Rouault’s “Head of a Young Boy”. She even made an oil copy of Picasso’s “The Absinthe Drinker” and hung it over the TV. So, I grew up in an environment hospitable to art and to the idea of being an artist. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be one.

LG: You studied at Indiana University in Bloomington during the late ’60s and then onto the Art Institute of Chicago. You’ve stated that you became more interested in photorealism and pop art, seeing it as being “hipper” than the traditional academic approach. Drawing and painting with precision back then ran contrary to the zeitgeist of those freewheeling times, how difficult was it to learn the kinds of representational skills you needed? Does your experience from then influence your teaching today?

Nancy Grimes: For me, learning how to paint isn’t a process of acquiring skills (a term I don’t like). It’s about learning how to look at and think about painting. To be a good painter, you need to understand why some paintings are good and how the artist made them that way. In my case, this understanding came slowly. I had to paint my way to it. This is true for every painter, of course. In order to become a better painter, you need to make paintings, and to make paintings, you need time and willpower. In grad school, I realized I didn’t know how to paint, but it wasn’t until after I graduated that I began to teach myself in earnest. I had the will, but I needed the time, which I had to find while working various tedious full- and part-time jobs. So, learning was a struggle and it took me a while. I was a late bloomer.

Yes, my experience as a student had a tremendous impact on how I taught. Except for figure drawing classes and a half-assed foundation course Indiana introduced in my sophomore year, I received no solid foundational teaching at the undergraduate or graduate level. At Indiana, the art history classes were good, but the studio classes were pretty hands-off. No one wanted to impose any sort of authoritarian teaching agenda. The study of precepts, theories, and precedents was considered very un-PC and inhibiting. In the SAIC grad department, students were concerned with the contemporary art scene and how they were going to fit into it. Grad school was a place where students found their brands. How can you learn when you already know it all? It was just a matter of figuring out how to sell it. (Unfortunately, this is still the case). As a result of this educational lack, I became determined to offer my students something more. I was very hands-on and my classes were structured. For most of my teaching career, I taught from life. I used models and set-ups in order to force students not only to look closely but to figure out how to organize a picture. I talked about composition and color. We did paint-mixing exercises and analyzed paintings. I introduced ideas about pictorial structure and emphasized the fact that painting is about relationships These were all lessons I needed as a student but didn’t get. I was like a parent who wanted to give their children the advantages they never had.

LG: What lessons were least useful to you as a student?

Nancy Grimes: Well, that foundation course I mentioned was pretty useless, but the most inappropriate advice I received from a teacher was to paint with a brush attached to a broomstick. Now, this was intended to loosen me up, but it really is an idea rooted in Abstract Expressionism, and its underlying goal is to transform drawing into mark-making—to separate line from form. I had no interest in pursuing this, and even if I had tried painting with a pole, I probably would have found a way to make the painting tight and controlled. I don’t have an Abstract Expressionist bone in my body.

LG: After you graduated what was it like getting your career as an artist started?

Nancy Grimes: It was hard. I moved to New York City on New Year’s Day in 1980 with about $2,000 in my wallet. My spouse was finishing his doctorate at the University of Chicago and followed a few months later. We moved into a shabby three-room apartment in Astoria. I used the best room as a studio and we lived in the other two. We had no money, no connections, and no prospects. It was not a happy time.

During the early 80s, there were still a few galleries showing hardcore representational art—Schoelkopf, Sherry French, Tatistcheff, Allan Stone—and I dutifully submitted slides to them all. Allan Stone nibbled, but when he saw the work, he shook his head and said, “You need to go to the Met and look at paintings. You need to learn how to carve out space.” He was right, of course. So, I put the career stuff on the back burner for a time and decided to focus on making better paintings.

LG: I heard you say in a talk that Georges de La Tour’s paintings have been influential, especially with regard to light. Would Leland Bell’s or Paula Rego’s paintings be another influence? Did you study with or come under the influence of Leland Bell?

Nancy Grimes: Leland Bell wasn’t on my radar while I was a student. I might have seen a reproduction or two, but he wasn’t an artist who grabbed my attention. I discovered Paula Rego later, as well. I immediately liked her work, but at the time I was painting still life and wasn’t looking hard at figurative art. Now, both of these artists are relevant to my work, especially Rego.

Back then, Chicago was THE place for outsider art and had a very competitive relationship with New York. You didn’t see a lot of contemporary realism there. I remember shows of Alfred Leslie, Janet Fish, and Jack Beal and was impressed by all of them, but generally speaking, post-Ab Ex representation didn’t have a big audience in the Midwest. Most East Coast influence came via art magazines, and I read them cover-to-cover. The articles that captured my attention were by Gabriel Laderman and Sidney Tillim, the loudest and most articulate advocates for the realism of the period. Their thinking aligned with my own and their arguments supported my belief in the value and importance of representational painting.

Looking back, however, I would have to say that George Tooker was my most profound influence. I discovered his work during my senior year in high school. Some friends of mine had picked up a hitchhiker—a hippie—who was traveling across the country. He decided to spend the night in Greenfield (where I went to high school), and a few of us gathered in his motel room to sample the marijuana he was peddling. Along with his dime bags, he had a copy of Avant-Garde–a cult magazine published in the late 60s/early 70s that was based in NYC and edited by Ralph Ginzburg—which had a big, beautifully printed spread of Tooker paintings. Now, this was the first time I had ever smoked really potent grass, and I became totally lost in the Tookers, studying them for what felt like hours. They were realistic, but uncannily so, and their silence seemed to stretch forever. All that alienation appealed to my teen-age psyche and my mind was thoroughly blown. I had never heard the term Magic Realism before, but I knew there was magic there, even in reproduction. A few years later, I saw a retrospective of his work in Chicago and was awestruck all over again. Tooker led me to La Tour.

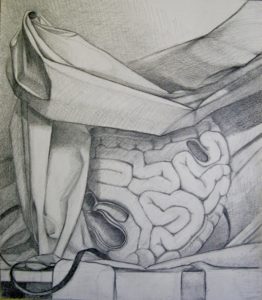

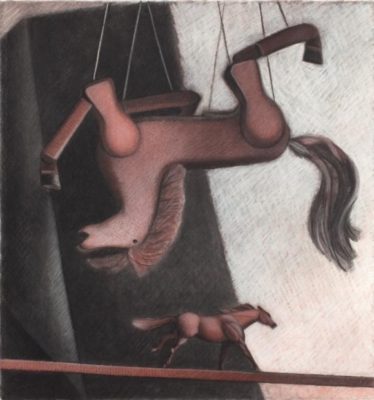

Study for Fortitude, pencil on paper, 14.5×16.25 inches

LG: Your process often seems to involve making drawings and/or oil pastel studies of a subject and then the oil painting. Can you say something about what this approach offers you?

Nancy Grimes: At one point, I realized that in order to improve my paintings, I needed to become more analytical about their formal relationships, which had begun to look tentative and flabby to me, so I began spending more time doing preparatory work. Besides subject matter and drawing, there are three major components to my paintings—composition, value, and color, so I separate these elements in studies. First, I do a compositional study, which is usually linear, then a value study in black and white acrylic, and, finally, an acrylic sketch in color. All this planning helps me work out the major relationships in the paintings beforehand, so I don’t have to constantly reorganize and rework the canvas. Of course, I always wind up departing from the studies at some point, either because I want to tweak the content or because changes are necessitated by the shift in scale from small to large.

LG: What are some of your most important considerations about creating space and light?

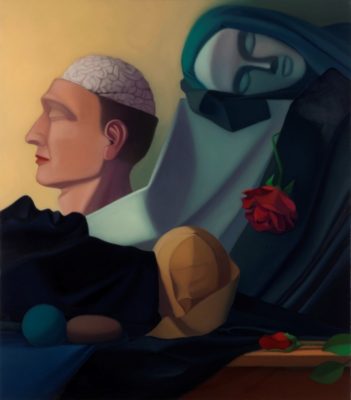

Nancy Grimes: This is actually a complicated question, which could be answered in a number of ways, but I’ll try to keep it simple. I need the illusion of space in the paintings because I want to create a fictional world—a world that is similar to but fundamentally different from the one outside the frame. I use space and color as ways to coax the viewer into the reality of the painting. Once inside, I want the eye to wander and linger, to stumble over and find things, to ponder and wonder. In the still lifes, I wanted the allegory to unfold and reverberate during the process of looking. In the figurative works, it is the narrative and the subtexts it generates that I hope to emerge.

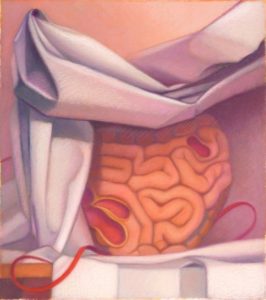

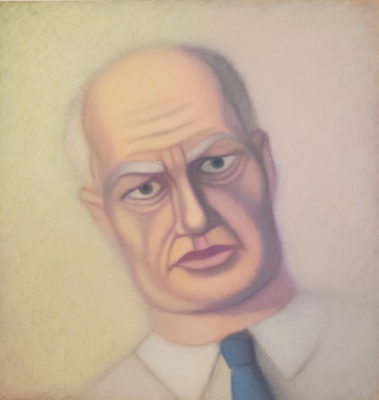

Light, of course, helps articulate space and I use it that way but, in my work, it is usually subordinate to shape and form. I often think of light in terms of key—some works are light, some dark, some mid-toned—but, generally, all my decisions about light and color are governed by ideas about content, expression, and mood. I recently made an oil pastel of the head of an old man. The generative idea was dissolution—the old man was passing into the light. I wanted his form to fade into a field of white. As an additional destabilizing device, I put the central axis of the head on the diagonal. Now, this idea changed as I was making the piece. Even though the overall key was light, I couldn’t bring myself to dissolve the form. I couldn’t let go of the solidity of the head and I couldn’t portray the man as fragile—as wasting away. Instead, what emerged was defiance, even anger. Yes, he is on his way out, but he isn’t happy about it.

LG: There is a simplified softness to your modeling–balancing classical modeling with modernistic flattened form. What can you say about this? Is making illusionist, volumetric forms important to you?

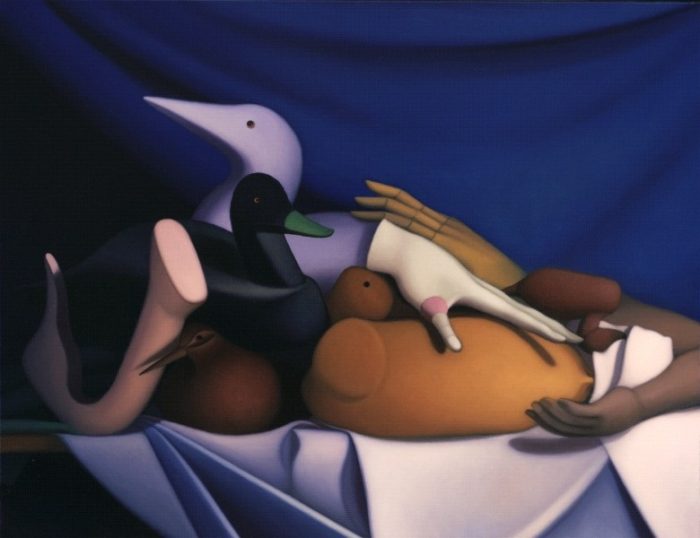

Nancy Grimes: You are right about this. Sharp edges flatten; softer edges help turn form, which creates space. Because I’m interested in gravity and weight, particularly in the still lifes, I want to give fullness to the forms without a lot of fussy modeling, which breaks up shapes and gives objects a rendered, too real, feeling. I think that the tension between form and shape—volume and flatness—contributes to the uncanny quality in my work.

LG: What would you say to a student who asked what’s the difference between painting plastic form and just painting an image?

Nancy Grimes: I think an image without plastic form is basically flat. It is an illustrated rather than a felt space. Plastic form has weight and mass. It can be heavy or buoyant, but It has a physical presence; it isn’t just a mirage. I think plastic painting (and I realize this is an old modernist term) pushes and fine-tunes formal relationships, so the image has a visceral impact. It establishes tensions that can be felt as well as seen. Now, I wouldn’t expect students to fully understand this explanation, but it would, I hope, challenge them to think about the concept of plasticity.

LG: Do you normally paint from an observed set-up, if so how important is the observation to you when the work is often more about allegory or meaning?

Nancy Grimes: Direct observation is not as important to me as it once was, but I still begin with a set-up. Putting together a still life is part of the composing process. I start with a firm idea of the size and shape of my support, then use a viewfinder of comparable proportions to see how the set-up relates to the rectangle as I put it together. I work from lists. I’ll have an idea for a painting, then make a list of the stuff I want in it. Over time, I collect the appropriate objects, then throw them onto a table or shelf and start moving them around. I might add or take something away, but orchestrating the objects—putting one thing next to another and positioning them in space—is how I develop the allegory or narrative. In the process, unexpected things happen, which often affect the meaning of the work in significant ways. I can’t just imagine a scene. I need to build it and see it in front of me. As I mentioned before, I’m interested in gravity and weight, so I need to see how objects sit on a plane, how they balance against each other, where shadows fall and what shapes are made by the spaces in-between things. Of course, the set-up is just the beginning. It’s a springboard and is always heavily edited during the painting process. Sizes and shapes are changed, unnecessary details omitted and colors are altered and heightened.

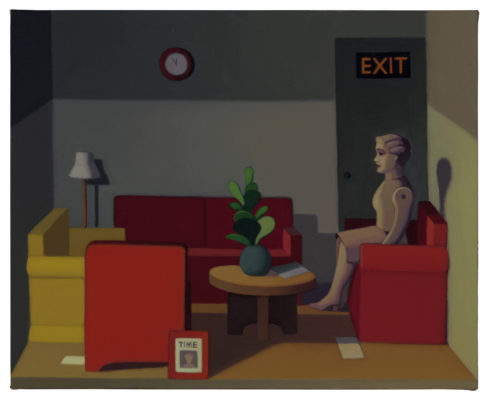

LG: Many of your works involve staging grouping of mannequins, do you have a mannequin collection or are these largely inventions of some sort?

Nancy Grimes: I do have a few mannequin parts that I’ve collected over the years but, more recently, I’ve been working with dollhouse figures, and I have quite a number at this point. I particularly like the dolls made by Renwal in the 40s and 50s, because they look unhappy (apparently, dolls didn’t cheer up until after the baby boom) but recently I’ve added more contemporary figures. The type of doll I use in any given work depends, of course, on the narrative. Initially, I painted the dolls as dolls, but now I’m less interested in the fact that they’re playthings, and I’m treating them more like stylized figures.

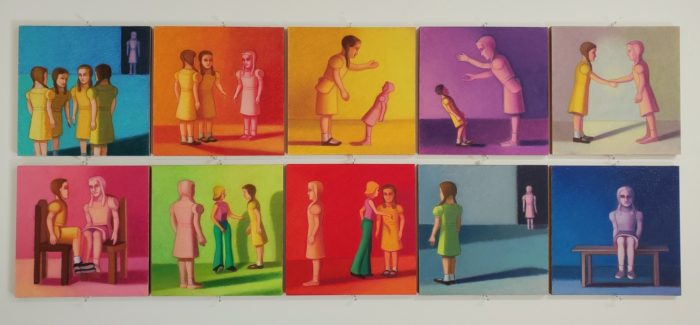

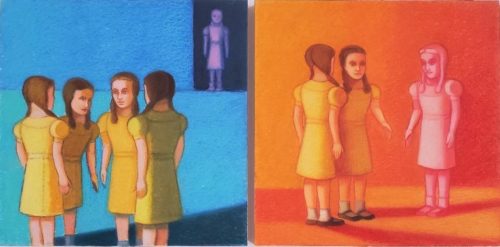

LG: Can you tell us about your recent group of 10 oil pastel paintings, Friends? I’m curious to hear about how these works came about and your use of color.

Nancy Grimes: I’ve been interested in contemporary narrative painting for some time, although until recently there hasn’t been much of it around, and opinions diverge widely on what it actually is. For years, I had heard the term bandied about by Pratt’s faculty and students, and it became apparent to me that no one knew what constituted a narrative painting now. The term was applied to almost any figurative work and was virtually meaningless. As a former writer, I believe that language should be specific, so I began mulling over the problem. It seemed to me that time—the unfolding of events in a logical, coherent way—is the missing ingredient in so-called contemporary narratives. Much of the figurative stuff that is touted as narrative is actually allegory. In most of these works, images are jumbled together in what are essentially painted collages, which aim to provoke thought about extra-painting issues and ideas. You see a lot of this type of painting in art schools, and its spiritual antecedents are Neo Rauch and Nicole Eisenman, among others. Now, some of this work is very good, but it isn’t narrative.

Because I was dissatisfied with the idea of collage as narrative, I gave myself an assignment. I would tell a straightforward story in a work that couldn’t be mistaken for anything but a narrative. To do this, I needed a plot—something that, in the best Aristotelian fashion, would have a beginning, a middle, and an end. I decided to describe the arc of a friendship, which would unfold sequentially in a series of small oil pastels. (Here, I must acknowledge a debt to the painter Patrick Webb, whose paintings about the travails of his gay protagonist, Punchinello, have greatly influenced my own ideas about narrative.) For my anti-heroine, I chose an adolescent girl—a character based on a Renwal “daughter” doll, which appears in previous paintings as a stand-in for my younger self. In “Friends”, I employed the simplest means possible to tell her tale—gestures are minimal; compositions, rudimentary; color relationships, clear and simple; all unnecessary detail eliminated. I wanted to use color more expressively than I normally do, so I assigned each panel a color atmosphere that is keyed to the action. In other words, I wanted color to reflect what the main character was doing and feeling, as well as the overall mood of each scene. Color was also a way to complicate the structure of the entire work. I didn’t want a string of visually repetitive squares. I realized that I was actually making a drawing on a semi-grid pattern and I thought color would help organize and activate the grid.

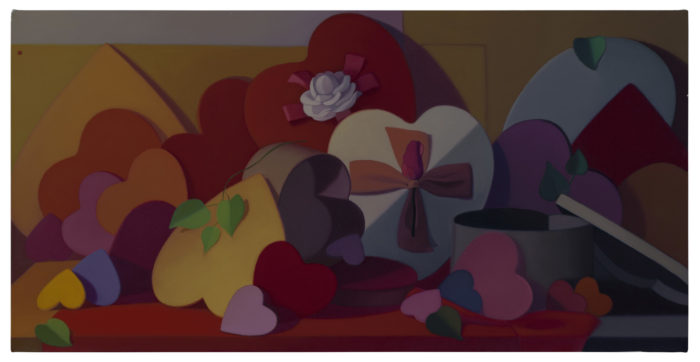

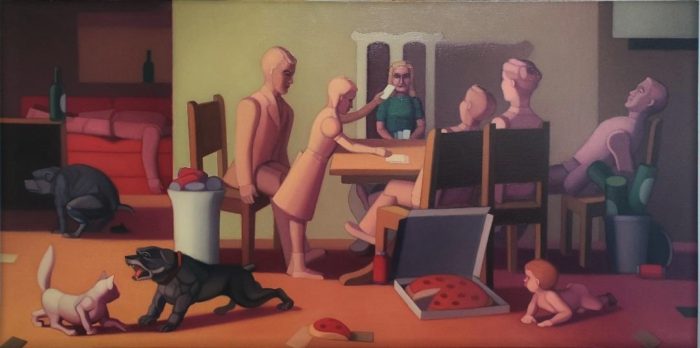

LG: Many of your paintings, like your Euchre, suggest multiple meanings and perhaps allegories. Euchre is a type of card game but means to deceive or outwit someone, the spelling also suggests the Eucharist, the mannequin figures’ Last Supper-Esque configuration, the unruly dogs and men’s zonked-out poses all suggest the painting is likely to have many symbolic meanings. Can you tell us something more about how this painting came about, your process here, and whatever else you might wish to say?

Nancy Grimes: Euchre is the third painting in a series about familial relationships. The original idea was “family circle”—a square composition that would show a family seated around a circular table. Over time, however, this idea changed and grew into something more personal and complex. I had been looking at the genre scenes of Jan Steen, which often depict households in disarray and moral decline. These reminded me of the card games my family played during our “together” times when I was a teenager. Now, these always began in fun—with lots of drinking and eating—but frequently they erupted into bitter, to-the-death struggles between my older sister and me. Euchre is loosely based on these contests.

With their stiff, almost Egyptian postures, I thought the Renwal dolls were good representations of repressed white people. Euchre shows them attempting to have a good time, while the more animated animal figures act out their suppressed aggressions. The figures’ positions at the table, who’s next to whom, indicate the internal relationships within the family—the daughter who seems to have the upper hand, the high card, stands next to the father; the brother leans against the mother figure passively watching rather than playing the game. There’s a lot going on here, but the kernel of the story is the competition between the two daughter dolls. There are strong autobiographical underpinnings to this painting, but it could be about almost any family. It is intended as an archetypal scene of sibling rivalry and familial dysfunction

.

No, I wasn’t thinking about the Eucharist when I painted Euchre, although I have used symbols of the Eucharist in earlier still lifes. I do, however, love this interpretation! This is why some critics say that the viewer completes the artwork. The audience often reads a work in unexpected, surprisingly appropriate ways. A drunken card game as the Last Supper? Pizza and beer as the body and blood? An adolescent girl as Christ? Why not? The seated blonde doll does seem to be holding a strong hand, and I have to admit that leaving Indiana was a bit like rising from the dead.

LG: You have written for several art journals, including Art in America and ARTnews. you also wrote the book, Jared French’s Myths. Did you study writing formally or taught yourself?

Nancy Grimes: I did a little of both. I think you learn how to write by reading a lot. Reading gives you a feel for language and you unconsciously absorb how others use it. As for formal training, when I worked at The School of Visual Arts in the early 80s, as a perk, I was allowed to take classes. For a year, I audited an art criticism writing course. The first semester was taught by Carrie Rickey; the second, by the British art critic Jean Fisher. The class didn’t really address the mechanics of writing. It focused more on formulating ideas about art. I do remember one valuable assignment, though. We were asked to describe a dozen paintings, each in a single sentence. This was a real challenge because it forced you to do some rigorous self-editing. You had to throw a bunch of adjectives and adverbs onto the page, then either figure out how to knead them into a sentence or toss them.

Actually, I learned the nuts and bolts of writing from my spouse, William, aka Biff, Grimes. Over the years, Biff has worked as a translator, copyeditor, features editor, and writer. He’s a real pro and the best writer I know. He helped me edit my stuff before I submitted it for official scrutiny. We would sit down together and go over a piece line by line. As a result of these intensive, sometimes contentious sessions, I learned that in order to write clearly you must have a precise idea of what you want to say. Vague, fuzzy thinking produces murky, cryptic writing.

I began writing because I wanted to participate in the larger conversation about art. I was keenly interested in art world polemics and wanted to have a voice even if it was a small one. Writing was also a way to get my name out there. My work wasn’t ready to exhibit in any ambitious way, and in any case, the world wasn’t ready to receive it. There wasn’t much demand for allegorical still lifes, particularly ones about death and loss, so I channeled some of my ambition into writing.

Writing about other artists helped me understand and appreciate work different from my own and taught me to be a more generous critic. The real benefit, however, was that interpreting the work of others enabled me to see and think more clearly about my own. Essentially, for me, writing was a continuation of my education.

LG: 16. I’m curious to know more about what led you to art writing and about your Jared French book. Has writing about other artists changed your work in any way? For instance, Jared French’s enigmatic compositions and their surreal, psychological tensions seem to reverberate in your work.

Nancy Grimes: You are right about Jared French. I feel a strong attraction to much of his work and, in some ways, I identify with him as an artist. I didn’t encounter his paintings until 1989, when I reviewed a show of Paul Cadmus, French, and George Tooker at the Whitney’s outpost in the Equitable Building. During the 70s and 80s, the magic realism of French and Tooker, as well as Cadmus’s satirical, illustrational figuration were the antithesis of everything the art world valued. Nobody was looking at this type of work, and I hadn’t given my old flame Tooker a thought for years. So, the show was an epiphany for me. It reconnected me to Tooker, introduced me to French and gave me a greater appreciation of Cadmus. I felt much closer to these artists than I did to New Realists like Philip Pearlstein, Rackstraw Downs, Catherine Murphy, and Janet Fish, artists I admire but who are unwilling or unable to break free of an overriding formalist approach to representation. French’s interest in myth, archetype, and psychology, along with his classicizing impulse, appeal to me, as does his ambitious translating of personal experience—i.e., his bi-sexuality and puritanical upbringing—into mysterious, provocative images that resonate with meaning.

LG: Over the years you have been seen as a champion for painting, organized and moderated panel discussions in a number of venues with some leading painters in the NYC area. Many of the topics at these gatherings are about keeping painting and painters vital and relevant to today’s art world. You address the concern that painting doesn’t carry as much “cultural clout” as it once did. Back in the 1970s, the Alliance of Figurative Artists often had huge meetings of 300 or so painters that could get very combative at times with the painters most committed to their particular cause or camp,like those between the painters working expressionistically and those more inclined toward modernist and intellectual intent. Did you ever attend those meetings? I imagine there’s greater tolerance for differences and things are less polarized today than back then and exchanges tend to be far less heated.

Nancy Grimes: The Figurative Alliance was a little before my time, but I wish I could have attended those legendary meetings. The desire for that kind of spirited discourse was one of the reasons I moved to New York City. I had this fantasy about artists sitting in coffee houses locked in earnest debate. I longed for intense, heated discussions about art—the kind that tests your own ideas and values. What I discovered, to my dismay, was that New York artists not only shied away from aesthetic arguments, they were terrified to express any opinions at all, lest they offend someone and injure their career prospects. Most of the artists I met were so intent on self-promotion—on sucking up to more established artists and courting dealers and collectors—that they had little time, energy, or interest in talking about art critically or philosophically.

Over the years, I have met a few artists—a very few—who are as contrary and opinionated as I am, but most of these are painters who also teach and/or write. At Pratt, where I taught for over 20 years, there’s at least one teacher for almost every “ism.” Teachers love to talk, so it was easy to fall into lively, collegial discussions there.

LG: What has been your experience with leading your panel discussions? Have they given you hope for the future of painting?

Nancy Grimes: I suppose the panel discussions I’ve organized were intended to promote discourse, but I have no illusions about their reach or influence. The two I moderated at Pratt were tailored for specific political situations within the institution. At Pratt, Painting was, and still is, under constant assault from the other studio concentrations, which compete for students, space, and money. The Administration also pressures the Fine Arts Department to be less “siloed” and more inter-disciplinary, an agenda I believe weakens Painting and underserves the many students who go to Pratt to study painting. So, the panel discussions were really for students. I wanted them to feel that it was okay to be a painter, that they weren’t going to miss the bus of history if they painted. I remember an episode of Robert Hughes’ television series, “The Shock of the New,” in which he interviewed William Rubin. Despite his pivotal role in shaping the narrative of Modern art, Rubin said that, ultimately, artists, not curators, critics, or historians, will determine the direction and future of art. I was surprised by this, but I would like to believe it’s true. I hope that any artist—would-be or established—realizes they have the power to influence the course of art. So, if you want to paint, paint. Don’t be dissuaded by biased teachers, specious theorizing, or art world fads.

At the moment, I am very hopeful about the future of painting. There’s a lot of it around and much of it is pretty good. For me, the most exciting developments are in representational painting. Suddenly, the art world is flooded with painting that has something to say by artists of various colors, ethnicities, and sexual orientations. Whether black, gay, Hispanic, Asian, trans, female, or even straight white and male, these artists want to talk about who they are, where they come from, and how they experience the world. They have found new stories to paint and they are already affecting the direction of contemporary art.

Great interview ! Wonderful images filled with mystery and magic .

Thank you, Nancy, Thank you Larry. This is a great interview of a very fine painter. The work looks wonderful and I am intrigued by your point of view about allegory.

I enjoyed this interview a lot. Whenever I see paintings that employ geometric lines and shapes I always wonder what the artist is thinking. These paintings are so sharp yet soft and they are so eye-catching. The horizontal and vertical lines in some paintings give a feeling of stillness and power and the use of geometric shapes with soft edges is genius as it gives contradictory textures but go easy on the eyes. Great journey and art!