Interviewed by Jeffrey Carr

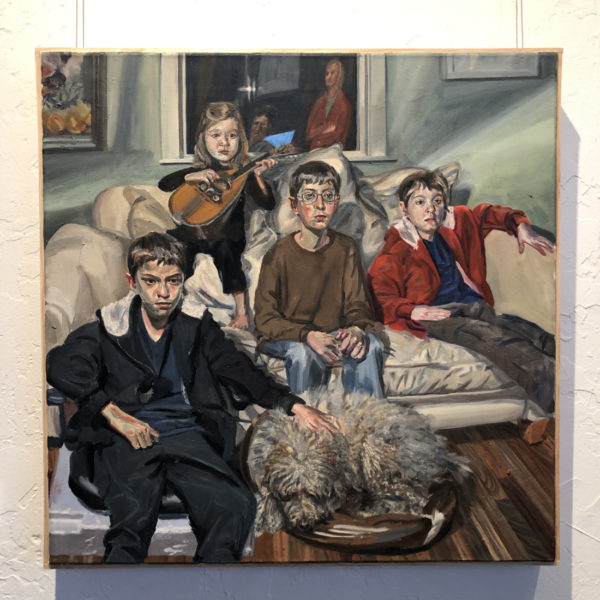

About an hour north of where I live in San Diego, California is the Oceanside Museum of Art, which hosts a biennial juried show. In 2020 I was looking at the catalog for this show and immediately noticed a prizewinning large-scale family portrait by a local artist whom I did not know; Michael Sitaras. The portrait was vividly realistic and beautifully painted, from what I could judge from the online catalog. We made contact soon after, but then the Covid pandemic intervened and it was not until recently that I was able to visit him at his house and studio in Carlsbad, California. His paintings are extraordinary and very accomplished. Michael himself is also extraordinary; the only painter I know who is both a very good painter and also a Greek Orthodox priest. How did he manage to achieve this amazing combination? He and I have had a few conversations about his career and his painting, and he has agreed to respond to some interview questions.

Michael Sitaras got his undergraduate degree from Syracuse University in the seventies, and his MFA from Louisiana State University. He also attended the St. Martin’s School of Art in London in the mid-seventies. In addition to being an artist, he is the Pastor of Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church in Cardiff-by-the-Sea. He has participated in more than 20 exhibitions in galleries and museums throughout the United States including several solo exhibitions. He received a juror’s award in 1983 from critic Dore Ashton for the Miniatures exhibition at BACA in Brooklyn. In 1983 Sitaras also helped sculptor Michael Heizer assemble Dragged Mass Geometric in the Whitney Museum and constructed sculptor Dennis Oppenheim’s Rolling Abacases for the Sander Gallery, SoHo. A solo exhibition of Sitaras’ work took place at the Sander Gallery in 1986. More recently, his work was exhibited in 2019 at the St. James-by-the-Sea Episcopal Church Art Gallery in La Jolla, California.

Jeffrey Carr: Michael, tell me about your training as an artist. You’ve told me that you were born in Greece, and that your father and grandfather were Greek Orthodox priests there, a situation that influenced your later decision to join the priesthood. You’ve told me how much your art influences your ministry. After your family moved to the USA, you got your undergrad degree from Syracuse and an MFA at LSU. You also did some training in England, at the St. Martin’s School of Art. What experiences influenced your development as an artist while growing up and later during art school?

Michael Sitaras: When my family moved to the USA from Greece, we lived up and down the East Coast. When I was in high school we moved to South Florida into a town that was the home of Albert E. Backus. Everyone called him Beanie. He was to be a great influence on me, although I did not know it at the time. Someone introduced me to him and soon Beanie invited me to paint in his studio. I was fifteen when we met. Every day after school I went there to paint until I entered Syracuse University. Some have called him the most important Florida landscape painter of the twentieth century because he influenced many people, including the art movement now called the “The Highwaymen”. The Highwaymen, also referred to as the Florida Highwaymen, are a group of 26 African American landscape artists in Florida. They challenged many racial and cultural barriers.

The Highwaymen have reached great notoriety in the last few decades. He welcomed many of them into his studio, just as he did me and many kids my age, some of whom became artists in their own right. Because of him, I got commissions to paint judges, senators, and wealthy people in South Florida. I never painted landscapes while I knew Beanie, although I watched him paint them. I knew his palette, his method of mixing on glass, and how he cleaned his brushes in a wire-meshed tray and shaped them with sandpaper.

During that time he gave me a grant to study at the Art Students League in the summer of 1970. There I studied with Edwin Dickinson for a brief period as well as Marshall Glasier. After college, I knew that if I wanted to get my name out there I could not bypass New York City, even though the idea of going there from middle America was scary. At 24 I set out for NYC with a friend and got a place on 1st Ave and St. Mark’s place in the Lower East Side. I made many night paintings of the streets across from my apartment. I had to acclimate myself to my environment before I felt like I could continue with anything else. I took my slides around from gallery to gallery and landed some group shows. It wasn’t until I worked for Dennis Oppenheim, who showed with Sander Gallery, that I was able to get to know the owner Gerd Sander who was the grandson of August Sander. Gerd just passed away in Cologne, Germany, but I remember him being very kind to me as an artist. He showed my work in the 80s and gave me a one-person show in 1986.

JC: Your portrait and still life paintings seem to me to be in the English tradition of direct, perceptual painting as practiced by Stanley Spencer, Coldstream, Uglow and of course, Lucien Freud. Is that fair to say? But in your abstract paintings, you demonstrate a special affinity for some of the abstract formalist artists of the seventies and eighties. An unusual combination! What art and artists have informed your sensibility?

Michael Sitaras: You mentioned some important British painters. Augustus John would be in that group, too. I also look at Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, Graham Sutherland, David Hockney and Anthony Caro. I don’t need to mention the influence of the Beatles, the Stones, and the Sex Pistols. We were all invaded by the British, weren’t we? Yes, all of the artists mentioned above are in my work as well as the French, like Delacroix, Monet, and Vuillard. Certainly, the greats like Velasquez, Rembrandt, and Vermeer are painters that I always look at.

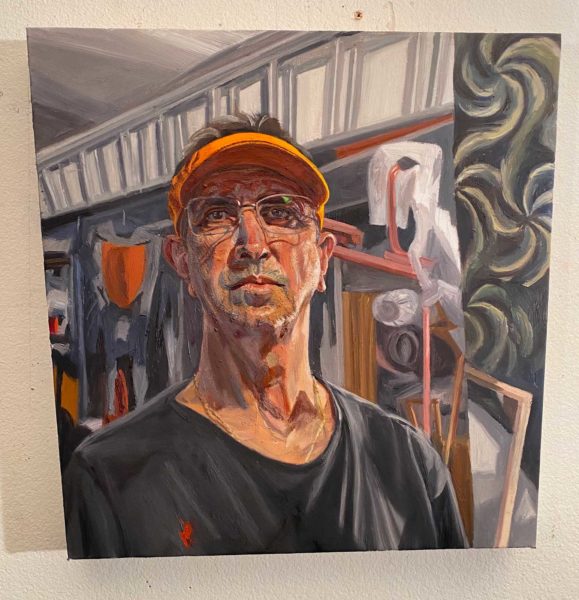

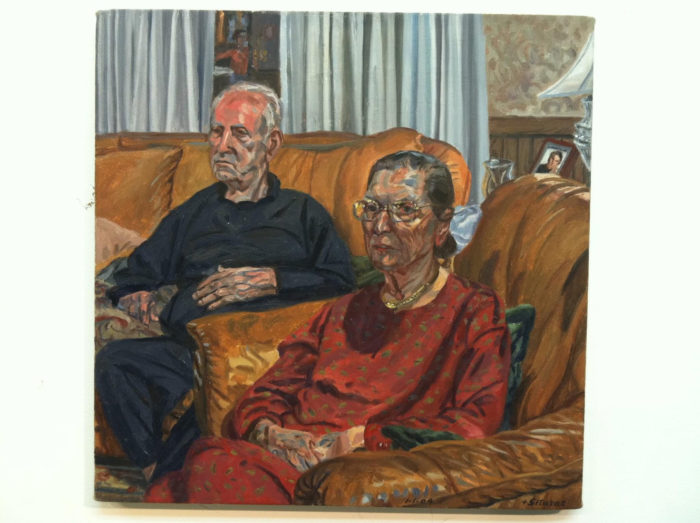

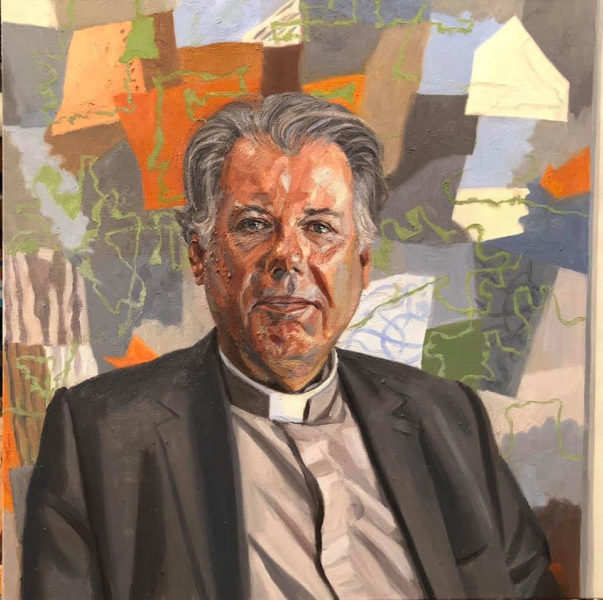

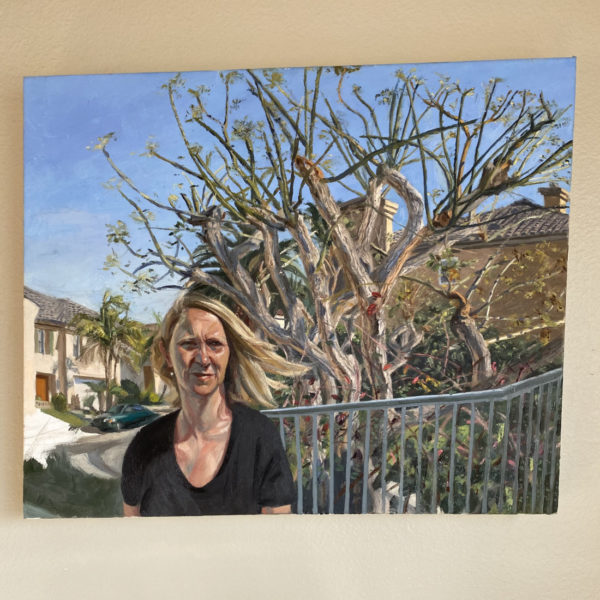

Speaking of British art and Francis Bacon, the former director of The Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego is an expert on both. As we speak I am painting a portrait of him, his wife Faye, and their two dogs. The work is in progress so I can’t show it now but I have done another one of him and Faye separately that is included here. In his thirty-three years as Director and CEO of MCASD, Hugh has really put San Diego on the map in the art world with many groundbreaking exhibitions. He has also been a great friend to me.

It’s important to note that Cezanne brought about the Braque/Picasso Cubist explosion and propelled us into a new way of looking at the world. I still look at Cezanne as a source of inspired tenacity and single-mindedness. I am drawn to the German expressionists of the 20s, the abstract expressionists of the 50s and the neo expressionists of the 80s as well as to Pop art, color field, minimalism, and the super realists of the 70s. I look at Philip Guston, Alex Katz and Jerome Witkin (who was my teacher at Syracuse).

I also love to look at Brice Marden, Richard Tuttle, and Elizabeth Murray’s work. Every artist offers a gift and so you take what you want from them. I was particularly drawn to the minimalists like Sol Lewitt, Donald Judd, and Robert Ryman, even though my work was worlds apart from theirs. For me, there was that and there was me. It made sense. Why couldn’t I love these artists? They were dealing with the same things I was, but in a radically different way. It was still about light, form, and color.

I have a special affinity for Dennis Oppenheim and Michael Heiser, both of whom I worked for in NYC. I constructed the rolling abacuses for Dennis Oppenheim that were later shown at Sander Gallery. All he gave me was a rough drawing of the project. I chose the materials, the thickness of the wire, the kind of wood, and even the color and size of the beads, and the constructions were various sizes from inches to feet.

I also worked for Michael Heizer, helping him construct a silk-screened cardboard version of his “Dragged Mass Geometric” at the Whitney. The piece was an attempt to engineer and recast in the form of a three-dimensional drawing of an earlier earthwork he had done fourteen years prior with a huge square boulder pulled by a tractor into the ground displacing the earth around it. During the installation, the crew from the television program Sunday Morning with Charles Kuralt came and filmed the construction of the work. I was the guy in the yellow tee-shirt rolling on the glue in order to attach another piece of cardboard. People told me they saw me but I never saw the show myself.

JC: You are the unusual combination of an accomplished artist and the pastor of a church. In our talks, you described being an exhibiting artist in the Soho of the 1980s and then deciding to go to seminary to become a priest. How did you combine these two very different vocations?

Michael Sitaras: Good question! I honestly don’t know how to answer it. If anyone asked me if becoming an artist was a good idea I would say – no – do something else. Likewise, if anyone asked me if becoming a priest was a good idea I would give them the same answer – no – do something else. It’s only when you feel like you have no other options that you become an artist or a priest. They are perhaps the two most difficult professions but both are very fulfilling. I was guided by what I like to call, “GPS” (God’s Positioning System). Being an artist or a priest was for me a GPS moment. The constant in art and in faith is truthfulness and honesty.

When I lived in my Broadway/Prince loft space in the 80s I started to develop a feeling of my mortality. I found myself wanting to give away my work and I felt a tremendous sense of loneliness. It was overwhelming because I always thought that being an artist in NYC was the be-all-end-all. After my one-person show in the mid-eighties, I experienced a deep depression as I think some artists do after a show. Life just seemed to go on as it did before. I was not in a good place. I thought that there had to be something more than being alone in a studio practicing what I perceived to be oblivion, an artist’s worst nightmare. So I remembered my youth in the church and sought to elevate my thoughts to a brighter place. It worked. I never felt that I chose the priesthood as much as it chose me.

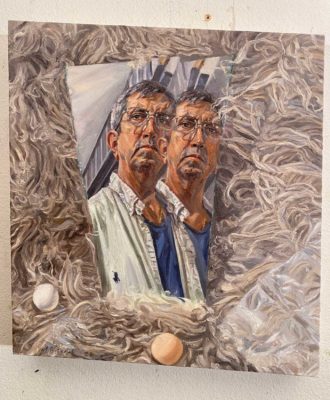

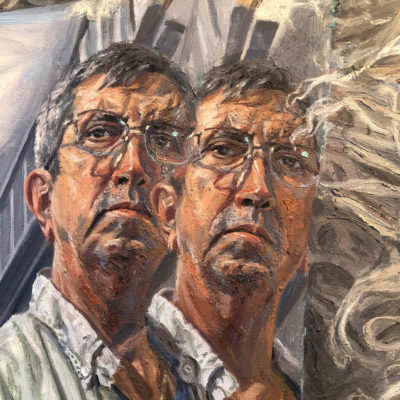

JC: I really respond to your portraits. Your portraits of faces and figures- and of dogs- seem to be deeply observed and highly detailed, but without the look or feel of photography. The faces and figures of your sitters, especially your family, seem to be intensely alive and evocative as individuals. You also do wonderful self-portraits. What is your attraction to doing portraits?

Michael Sitaras: We all have two eyes, one nose, and a mouth and yet each is different. Portrait painting is a precarious and disarming experience but it’s very satisfying when it works. When I paint someone I take many iPhone pictures and have them available to me while they sit. When our session is over then I may use those pictures as a reference if I decide to continue in the studio. Lately, I’ve been working both on location and in the studio. What I have started doing lately, with the advent of the iPhone and iPad, is a series of digital drawings and pictures of the sitter and having them available while they pose. Photographs by themselves are very seductive and hard to depart from, so drawings allow me more freedom while real life gets correct color, motion, interaction, and fellowship. It’s a way to understand a person in depth. Lucian Freud was a master at penetrating the psyche of his sitter, though his work was more about him than the sitter. In that sense, for an artist, each painting is a self-portrait.

I love the act of painting as I know you do. Paint has to work with the stroke and with the form and they can’t tell on each other. It should never be about working from life or from a photo or from memory. It should just work. I have to be stimulated and challenged or else there would be no reason to paint. I feel like the painting has to go beyond me. I love looking at a piece of work and not being able to figure out how the artist painted it. You see that with all the greats. In order for me to fool the viewer, I have to fool myself. The challenge is not knowing how I got to a certain place in the painting because it has to be bigger than me and it has to transcend. I can never put myself in a position where I can do it again. Manet said that anytime he paints he feels like he is diving into cold water. I like the challenge of going beyond the place I would normally stop in the painting. I like to risk destroying it, to chance that the painting can be ruined if I go further. When I go beyond the “finish” mark then it doesn’t become precious anymore. It becomes a challenge and I stop when it hurts. Sometimes I beat the work and sometimes it beats me. I honestly can’t tell which is better.

JC: As I write this, there is an exhibition of the portraits of Alice Neel up at the Met. Her work is about people, and so is yours.

Michael Sitaras: I met Alice Neel when she came to Syracuse as a resident artist. The eclectic quality of her personality was equaled by her work, although she was very gracious. Her paintings clearly reflect her personality and reveal her risk-taking. For instance, her painting of Andy Warhol with the gunshot wound was as much maternal as it was voyeuristic. To share pain with others is a step towards healing. In the Warhol portrait, I saw a man who had found another artist who could exhibit his pain, as well as an artist who had found in Warhol a way to tell a story of vulnerability. It’s hard to look at that painting. You’re almost not supposed to. I mean, it’s so personal and revealing. It’s voyeuristic as it lures you into riding on every luscious virtuosic stroke in her idiosyncratic method of pushing paint around. She took a man who hid himself in his public persona and exposed him in his most raw state. That was genius.

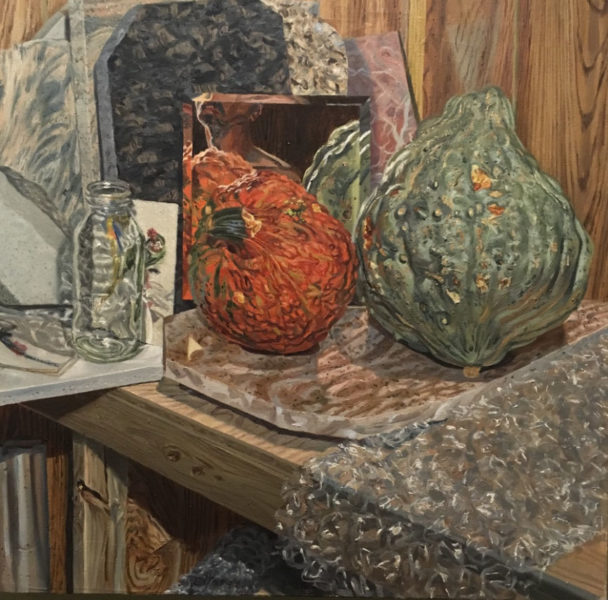

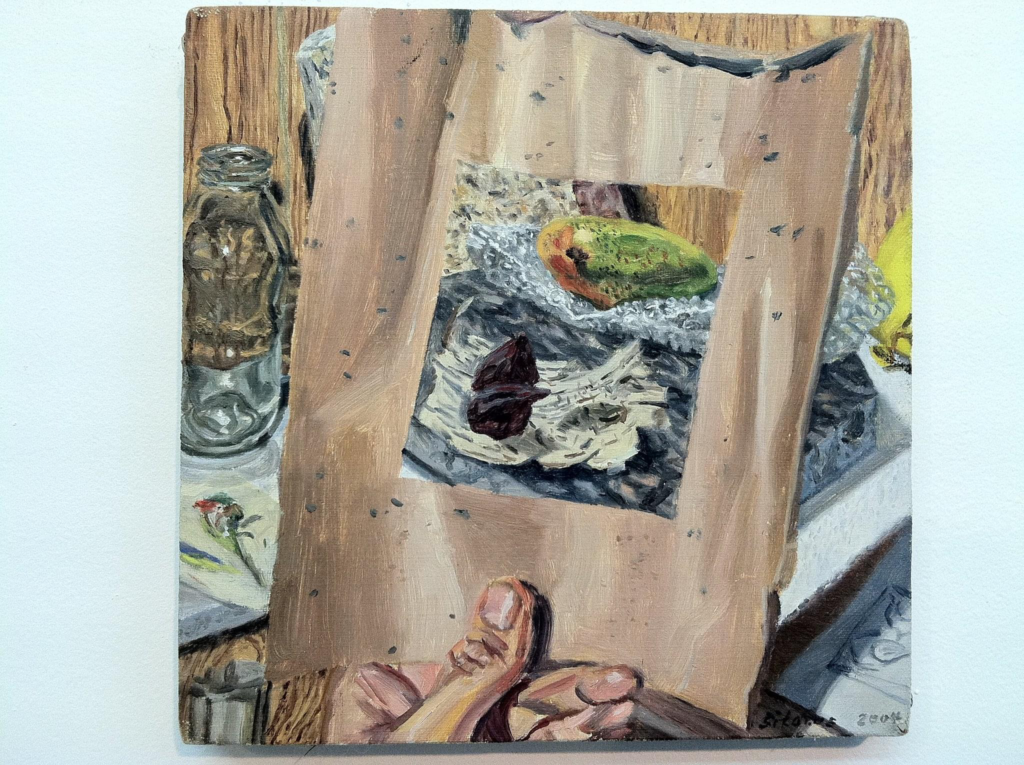

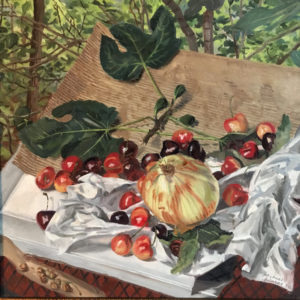

JC: Your still lifes seem very different from your portraits. Your portraits are of people and dogs; pretty traditional portrait fare. But your still lifes portray things like blocks of wood and bubble wrap. I don’t remember ever seeing a still life with bubble wrap before. What are you after in your still lifes? Is spirituality an influence?

Michael Sitaras: You are observant to make that distinction between my portraits and my still lifes. It’s good to see it from another perspective. In his autobiography, David Hockney said, first off, that you can never believe what an artist says about their own work. Having said that, I feel that both my portraits and my still lifes are similar in terms of broken space and planar values. I break up my portraits in sections, sometimes creating invisible geometric shapes within the facial features. Those shapes are more readily seen in my still lifes, landscapes, and abstractions. For instance, the figures in my family portrait are sectioned out by geometric shapes. That’s why I painted my geometric painting in the background. The cubic quality of the abstraction informed the cubic quality of the facial features and of all the other objects. The V shape of the abstraction became the V shape of the movement in the painting.

You ask whether spirituality informs my work. It does by virtue of who I am as a pastor but I don’t set out to make religious paintings. I don’t paint iconography as an object of veneration, but my work is a product of who I am. The symbols I use are subtle but I do use them. I’ll give you one example from your mention of the bubble wrap. I think of bubble wrap as the church or a group of people adhering to an ideal or a treasure. In order to transport that treasure it is essential for it to be protected by bubble wrap. As long as the bubble wrap surrounds the treasure, it is as valuable as the treasure. Having said that, the bubble wrap itself has inherent beauty. It’s a plastic, pop-able, shiny, utilitarian substance that isn’t a conventional subject matter for a still life. It’s just a great aesthetic subject. I love painting it.

I once made a painting of bubble wrap on top of paneling. I chose the bubble wrap over the wall paneling because I liked the way the shadow appeared through the bubble wrap. When I painted the sections of the bubble wrap, I looked at each section as a kind of portrait rather than an object. Each of these little bubbles in the bubble wrap was like a face, little soul or a cherub. I would actually put masking tape next to the bubble I was painting in order to know where I was and so each bubble would be its own “person.”

I have adapted other iconographic symbols in my work such as wood as a symbol for strife or stone as a symbol for mortality. The problem with using symbols as a code for something else is that you can lose the original meaning. As Sigmund Freud is said to have said, sometimes a cigar can just be a cigar. So, when I select a subject to paint I don’t think much about the object for what its symbolic value is to me. I just choose it because of the challenge of painting it. I started painting bubble wrap before I ever thought of what else it could represent.

When I was in New York, I made a series of cloud paintings that I liked to think of as illustrations of Homer’s Odyssey. These are the paintings I showed at Sander Gallery. They were all curved canvases depicting Odysseus’s journeys. All were painted from above the horizon line so you could only imagine the narrative below. Remnants of the story would be seen in the cloud/smoke formations. In one of them, our Greek hero Odysseus went to the Island of the Dead and made a libation to the gods by pouring wine over a fire. At the libation, Odysseus extracted the smoke image of Agamemnon and also one of his mother whom he didn’t know had died while he was away. In his conversation with his mother he found out that she would have been glad to live her worst day on earth rather than be in Hades, where, of course, everyone went as they believed in those days. So, the smoke image appealed to me and I started painting these swirling strokes that looked like cloud/smoke imagery laced with little faces.

JC: You paint portraits, still lifes and landscapes. But you also paint beautiful abstractions; employing pattern and shaped canvases. One unspoken rule in painting is to find your “thing” and stick with it. You obviously have a number of approaches. What are you after in your abstract paintings that might be different from your perceptual paintings? And in what ways are they similar?

Michael Sitaras: I heard Duane Michals say once that nothing is new except the present. I am my own painter and I am an individual in the world. Yes I take from many artists and I celebrate their influence but ultimately when I am in my studio, it’s me and no one else. I try to push out my audience. Everyone develops a walk and talk and syntax that is hard if not impossible to change. Painters are no exception. It doesn’t matter what one does over time it will be consistent if the artist works through it. They will have a “thing” as you beautifully put it. If one works long and hard enough then it will make sense in the oeuvre of their work.

The real question is, can an artist do several things at the same time without seeming to appear derivative? Being typecast can be as horrible as it is good. When you look at Gerhard Richter who paints squeegee abstractions right next to his very realistic “photographic” paintings, you realize that the conceptual link is the photograph. Lucio Pozzi works well in all mediums from video to installations to well-painted watercolors. Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg and many others have not allowed themselves to be “pigeonholed.” Philip Guston fell into that abstract expressionist groove and then started painting comic figures that made him, for a time, anathema within the art world. Everyone has many facets to their personality. We have the luxury of following important radical artists. Why not assimilate and use what they taught us and put it in our work? I pay homage to them all the time by referencing their work in some way. I also pray for the souls of those departed. It’s another way of paying them homage.

With my recent abstractions, I had a strong need to paint space and to just put paint down. This was because of some personal strife that I was experiencing at the time due to the deaths of some of my parishioners. I just started painting green blobs (representing souls) as a way to comfort my grief. A kind of green that you would find in the spring, I call it resurrection green because it represents new life. With each painting, those blobs started connecting and I quickly recognized that they symbolized the souls of those who had died connecting to each other in some way. Each area of the abstraction evolved into color field moments that reminded me of different artists I admired. I loved that! It was all I could do for a year and then I stopped. I couldn’t do it anymore. I had satisfied that longing. That’s when I painted another family portrait in front of one of those abstractions. So the two styles in one painting made perfect sense to me because they came from a similar evolution of thought. The actual abstraction was a discovery. The rendering of that abstraction in the family portrait was the revisiting of that discovery. It had become one step removed, just as the portraits were one step removed from life in the painting.

You mentioned the shaped canvases. They came about because of my rebellion against the square. I don’t like to be put in a cube, pun intended. I actually am a bit claustrophobic. Ellsworth Kelly, Richard Tuttle and Elizabeth Murray were pioneers in that break from the square. What I am doing now is not really a shaped canvas as much as it is a crooked canvas. What I discovered about an irregular shape is that it influences how I use the space inside. It sensitizes the picture plane. It’s like an itch that I have to scratch. If a picture is crooked on the wall I am constantly wanting to make it level. With a crooked canvas the forms that I paint within the picture plane are an attempt to correct the imperfection of the shape. That’s the tension. It’s similar to how Van Gogh paints bright colors next to one another. When the eyes squint the colors work in the form but there remains that vibration. It’s a similar stimulus when I paint within an imperfect square.

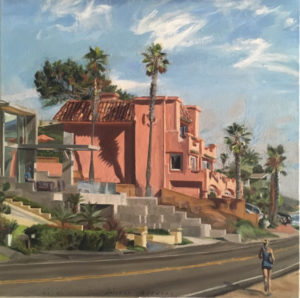

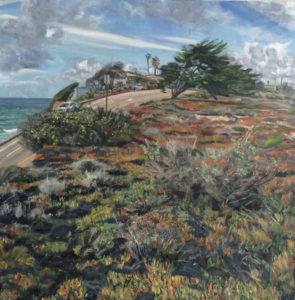

JC: Finally, say something about your landscapes. California has inspired a number of famous landscape painters from Diebenkorn to Thiebaud, as well as a flourishing genre of plein-aire painting. How do you relate to these traditions? What is it about the look and atmosphere of southern California that appeals to you?

Michael Sitaras: You know exactly what that is as a painter having grown up here and then been away for a time. I had never lived in California or even visited until way into my fifties. Diebenkorn and Thiebaud are two of my favorite California painters, along with David Park. When I first moved here I could only paint the landscape. Everywhere I looked seemed to be better than the last. It took me about three years of plein-aire painting to satisfy that itch. I could not depart from it without understanding where I lived. I knew that if I was to paint anything else I would have to make lots of California landscapes first. I remember seeing a retrospective of Richard Diebenkorn in the seventies at the Albright Knox in Buffalo. After a heavy snowstorm, a few of us students made the trek from Syracuse University. Seeing snow outside the large windows juxtaposed to those equally large, luscious, color fields of California suburbs was a moment I would never forget.

JC: As all artists know, the pandemic and the internet has completely changed the way we relate to each other as artists and how we participate in an arts community. What has been your experience with commercial galleries? How does an artist interact with this new online art world?

Michael Sitaras: The language of our digital age is rapidly changing and is doing so exponentially. It’s lucky that I have kids to help me navigate through it. They are my IT techs. Honestly, I just paint and it’s my passion. But I think it is important for an artist to have an online presence. If you don’t create one yourself then get someone who will do it with you. It’s just the world we live in.

As far as connections in art, the old adage of “who you know” still weighs heavy. However, we are in a new environment with social media. The internet has equalized the playing field a bit. Everything is up for grabs now. Diminishing are the ivory towers of commercial galleries where you have to walk around the cold reception desk to get to the exhibition space. Everything is turned upside down and sometimes the avant-garde online is seen alongside kitsch. You find that especially in NFTs where the virtual world is served with cryptocurrency. Everyone seems to have a venue. There are worlds that one can navigate so much more easily than before the internet. There are so many people online with so much diverse information and yet it seems easy to get isolated within your own thought group. The common denominator is money. If artists can set themselves up financially to be able to make art then they are golden. Ultimately, that’s what it’s about; finding a way to make your work.

JC: To conclude, being an artist can be deeply satisfying but also supremely challenging. What advice or encouragement can you give to both practicing as well as to aspiring painters?

Michael Sitaras: For practicing artists, I thank you for your contribution, your passion, and love for your work. For aspiring painters, push everyone out of your space and make art for yourself only. Just figure out a way to do it. Some artists choose teaching which is a great way to make a living while they make their art. I chose the ministry or shall I say it chose me but art has always been my constant.

A wonderful interview with a wonderful man. An amazing painter and an amazing priest..

Fantastic interview of a very talented individual from his paintings and how he views what he is seeing and from a spiritual perspective as the leader of our Orthodox Parish. Father Michael is respected in both, as well as a Father and Husband to his beautiful fsmily.

A fantastic interview with an amazing man. We are blessed to have him in our lives. He is an inspiration to us all,

Hello to Michael.

From your college roommate at Syracuse!

Love your paintings!

Michael Apicello

Mike whitaker here from Central always loved your talent. Mr Perdue painting was great and The Nancy Harris ink portrait awesome my friend