by Elana Hagler

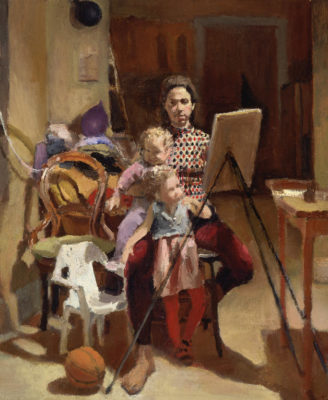

Katy Schneider is a painter and art professor at Smith College. She is a recipient of a Guggenheim and a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, and of awards from the National Academy of Design and the Academy of Arts and Letters. Schneider grew up in New York City in a family of nine. Her work focuses on themes related to her upbringing: making the most of a small space, organizing chaos and uncovering family dynamics. She has always been interested in the power of light to tell a story. Her work is in numerous collections, including The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the New Britain Museum and the Smith College Museum of Art. She has also illustrated several award winning children’s book. Among various awards she received the prestigious Bank Street College of Education’s Book Award.

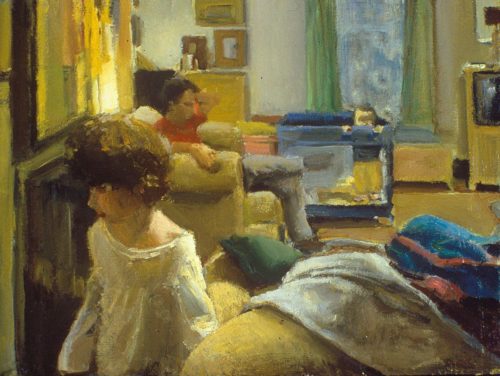

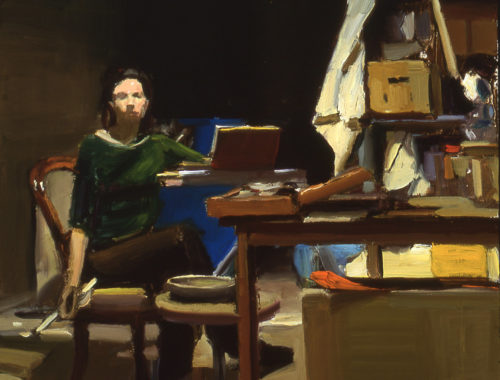

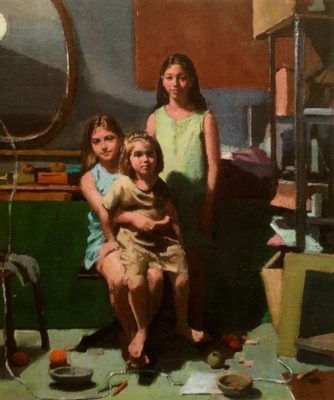

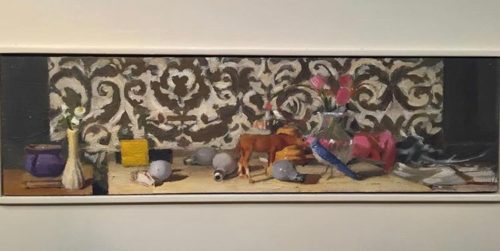

It was an honor to interview painter Katy Schneider. Her work is densely packed and deeply observed. Her paintings are scented with traces of Manet, Vuillard, and Velazquez, while remaining idiosyncratic and profoundly personal. Schneider composes with strength and authority…her hand imbues the weight of history onto the fleeting moment.

Elana Hagler: At what point in your life did you know you wanted to be a painter? Was this a direction that seemed to grow very naturally for you, or was there any internal or external opposition?

Katy Schneider: I planned to be a doctor. After taking a really rigorous painting class sophomore year, I realized that all I wanted to do in college was paint. To get a Yale degree doing something this fun actually felt like cheating. That was the internal opposition/questioning I felt. I wondered if I was avoiding “hard work” by steering clear of classes which were heavy in reading and writing; I was constantly zoning out. But I was hyper-focused with painting. I wanted to work all the time and was completely engaged. It felt so good to have what felt like a brain massage. This didn’t seem “right.” Work could equal pleasure? That’s not what I was taught. I got used to it though.

I don’t think I ever reached a point when I knew I wanted to “be” a painter. That’s true today. I just know that I love to paint, a lot of the time. But I’ve come to love doing many things. And I treat most everything I do as a creative endeavor, an artwork in the making. This semester for example, my teaching (Smith College) is transforming. I’m extra-fascinated by it suddenly. Like painting, (or making music—another interest of mine) teaching is about effectively communicating. Recently, I came up with a couple of new assignments and just shifted the order in which I present various ideas. Even adding one new color to your palette can dramatically change your paintings. This semester, the class feels fresh, more fun, more surprising; but it also fits together better, flowing more easily than ever before. I feel clearer and lighter. There aren’t as many paintings in my studio this month but I feel really full and very energized.

Looking back, the direction towards making my particular paintings grew very naturally. Early on I loved crafts. We didn’t have many materials so I became good at recycling and repurposing. I’d make little dolls out of our old cloth diapers and random scraps of felt. I painted about a zillion eggs. I’d blow them out and create ornate patterns with magic markers. When I was eight I made “the Mr. Smith series” of little books. As a teenager I drew my many siblings. I sewed, crocheted and played guitar. Everything fit in my lap and could be stored easily. It was a small, loud, busy place (nine people in a two-bedroom apartment). My work as an adult harkens back to this place. It’s all about making the most of a small space, ordering chaos. I repurpose scraps of board to paint on, no matter how tiny. Recently I made a bunch of one-inch paintings. Eggs and holey t-shirts from high school find their way into still-life set ups. People are crammed into 8 x 10 inches. I even spiraled back to books, illustrating several when I was in my forties.

In retrospect, all the making as a child probably functioned well to create some internal peace and quiet when there was very little externally. The act of making, even just sloshing paint around, calms my mind. The world is no less quiet now, so luckily I have my outlets.

EH: Many of your paintings have a very warm light to them. Do you tend to paint at night under artificial light?

KS: Yes, I always paint with artificial light. My lamps are the most important ingredient in what I do. I could paint with spaghetti sauce as long as I had my lamp to orchestrate the light and shadows and to construct the geometry. I usually paint in a corner of my basement with the window covered. Newer energy saving lightbulbs have been problematic. I like “old-fashioned” ones. I am often frustrated by how the paintings look when I take them out of the light in which they were painted. Lighting my easel as well as the scene I’m painting is a challenge. I often huddle to share the one light source. Adding two seems to wreck the drama I’m after.

EH: When I look at your work, I start to think of Manet, Vuillard, and even Velazquez. Whose work do you come back to again and again?

KS: I am a huge fan of all three painters. Vuillard is always in the back of my mind while painting. My teacher Bernard Chaet gave a talk in which he said we all have our own personal sense of geometry. This comment was memorable. I recognize something in a Vuillard (and in a Chaet) which feels familiar and powerful. The way he divides his rectangle resonates with me.

These shows really stuck with me: The Morandi and the Piero della Francesca shows at the MET in NYC. Stunning. I was really blown away by the Lawren Harris show of Canadian landscapes at the MFA in Boston (curated by Steve Martin). I was forever changed by the Alice Neel show which came to the Smith College of Museum. I hadn’t seen paintings of pregnant women before. All the portraits were so unpretentious, humorous and human. That show made me relax. Just plop people on a chair and start painting. I love the Dutch painter Gerard ter Borch. I am thrilled every time I come across one of his paintings. This month I found one in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Again, the abstraction, the geometry in all these painters I’ve mentioned, feels familiar, comforting and right. And, to be able to achieve this level of abstraction while being so detailed, so (seemingly) faithful to reality, is astounding to me. It is horribly easy to get illustrative while painting from life.

EH: You paint scenes of families, domestic chaos, portraits, and flowers, all in times past often misguidedly downplayed as feminine subject matter. The scale of your work is also as intimate as the genres. What stands out to me, however, is that you paint with a very bold hand, stressing shape and form over detail, with the strength of design and a rugged surface holding off any sentimentality at bay. Can you talk to us a little about your choice of subject matter?

KS: Thank you. I try hard to avoid cliché and sentimentality. I grew up with Kathe Kollwitz posters over my crib. Her lithographs of mothers and children were stories of depression and loss. They were dark portraits, the farthest thing from cute. Raising children is not all sunshine and I try to capture all aspects of being a mother in my work: love, boredom, sadness, distraction, mess, work. I will unabashedly paint babies, flowers and puppies. They have gotten a bad rap because too many people stop short, simply illustrating them. Aside from Kollwitz and Neel, most of my heroes for this type of subject matter are actually men: Manet and Fantin La Tour for flowers; Rembrandt, Velásquez and Stubbs for animals; Picasso and Sargent for toddlers.

I cried when I last saw Picasso’s First Steps. Sargent’s Neopolitan Children Bathing at the Clark in Williamstown is one of my favorite paintings in the world. It is deeply human. I have never thought of subject matter as feminine or masculine. I paint most everything except landscape which I leave to my husband, brilliant landscape painter Dave Gloman. Typically I am interested in painting a particular scene because of something formal I’m seeing—the abstraction (light, color, shape, etc). I’m interested in a balancing act between volumes and flat shapes, fuzzy and hard edges. I paint pregnant bellies for the same reason I paint peony buds. I paint smooth baby heads for the same reason I paint eggs–I love spheres.

I adore Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Lute, Check it out- She is such an egg. The one delicate, glowing orb of a head is so special because it is contrasted and supported by the flat, straight stuff—walls, map, chairs). 5% volume to 95% flatness. It’s so fake and so real. I can’t say I hear or think about music looking at her playing a lute. I think about an egg shell.

EH: I personally struggled with getting illustrative quite a bit, especially as a very young painter. What advice can you offer young painters on avoiding getting illustrative and why it is important to do so in the first place?

KS: Hmm, that’s a hard question. It might actually be helpful to say, “Hey student, I think you would be a great illustrator. You love detail. Your work would come to life, feel even more complete if it was accompanied by words, poetry, stories etc.”

If the student was sure they were not at all interested in illustration, 1. I’d suggest they copy great paintings using a big brush. 2. I’d suggest they tone a board, set up a strong spotlight on their subject and give themselves a (maybe a half-hour) time limit on painting the scene, starting with just the brightest brights. (Often this shows students how less is more.) 3. I’d suggest they do blind contour drawings and study why they might be enjoying looking at those.

Sometimes an overly illustrative painting can feel like a grocery list. One lemon, one egg, one cup. Sometimes it feels like lyrics that aren’t yet put to music. Melody and arrangement elevate and transform the lyrics. Light, color and geometry enhance the subject matter, creating the mood. There are so many songs I love but I must admit I have no idea what the words are. I feel the song, I don’t read the song. I remember my sister breaking up with her boyfriend and blasting “Wicked Game” by Chris Isaak on a drive. I know those words and combined with the melody and instrumentation, it is very powerful. I literally blew out the speakers that day. Simply reading the lyrics over and over wouldn’t have made the same impact. I think art should make an impact. A graphic novel like Roz Chast’s “Can we talk about something more pleasant” is a brilliant work of art. The drawings and the words work together to create something bigger.

I find myself illustrating almost every time I sit down to paint. Sometimes I have to overdo the details in an area so I can find the palette for the whole painting. It’s important though to realize when the details have to be simplified or completely wiped out. I don’t really know how to teach this. If there were a recipe, painting would be easy. And if it was easy I’m not sure I’d dedicate so much time to it. I like the challenge and the mystery. I want to be surprised by what worked.

I was first introduced to Katy’s work when she had a show at Wright State University in Dayton Ohio in 2000. I thought then and still do now, that her work is amazing!

I recently saw Ms. Schneider’s paintings at the Berkshire Botanical Garden’s show “Ecophilia” in Western MA. I returned twice just for the opportunity to stare longer at those paintings. I so appreciate how she turns rigorous visual analysis into something moving and beautiful. Very much love and respect her work. Also, thank you for the interview and great questions. You gave me lots of food for thought.

Katy, love the boldness and the simplicity in which you express yourself, by words and in the painting. Big embracing happening here with a strong love of life.

“I could paint with spaghetti sauce as long as I had my lamp to orchestrate the light and shadows and to construct the geometry.” Good stuff. Thanks for being so fresh.