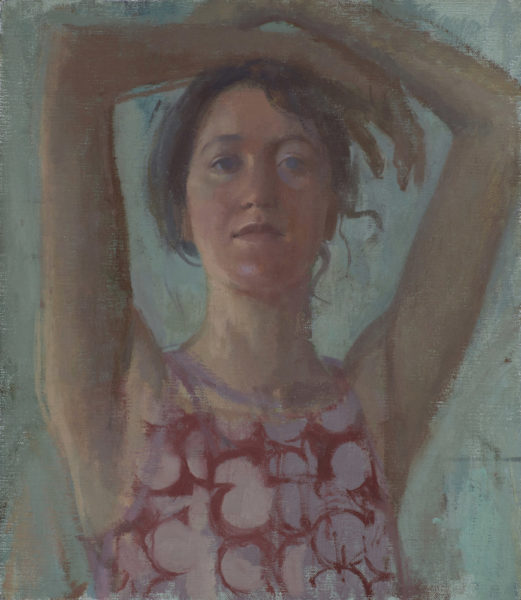

Several months ago I was impressed by Kathleen Hall’s self-portrait, Heat Wave, in the Prince Street Juried Show. This painting looks out at the viewer, arms draped over her head, resting and cooling from a hot studio. Her compositional economy and tonal poise seem to confidently exclaim that no mere heatwave will exhaust this promising young painter as she confronts the challenges ahead.

After a search to find out more about her I emailed her to find more about her art and was pleased that she agreed to an interview with me. I would like to thank Kathleen for her generosity in writing about her background, process, and thoughts about painting.

Kathleen Hall is a painter and educator currently based in Richmond, VA. She received her BA in French and Studio Art from the University of Virginia and an MFA in Painting from the University of New Hampshire. She has been an artist-in-residence at Yaddo, the Vermont Studio Center, the Alfred and Trafford Klots International Program, the Cité Internationale des Arts, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Kathleen has taught painting and drawing at multiple institutions including St. Mary’s College of Maryland, the College of William and Mary, UNC Asheville, and Centre College in Kentucky. Her work can be found in numerous private collections throughout the U.S. and France. —From Kathleen Hall’s website bio

Larry Groff: Your mother) Linda Carey and father Charles Hall(1951-2002) as well as you stepfather William Barnes are all highly accomplished painters; how did that affect you growing up?

Kathleen Hall: My parents always encouraged me creatively. As an only child, I remember constantly drawing and making things to keep myself entertained. One of the greatest gifts my parents gave me growing up was taking me to many museums. Even though we lived in Ohio, I remember visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the DC National Gallery pretty much every year. When I was a little older, between the ages of 10 and 14, my parents took me to France and Italy. I remember that they were very determined in their commitment to see great works of art in person – our trips felt more like pilgrimages than tourism. If I got tired, my parents would usually park me in front of a statue with my sketchbook so I could draw.

What I value most about those experiences, and still enjoy when I visit museums, is that sense of unstructured exploration: taking in a great amount of visual information in a short period of time, from such diverse sources, and responding to things instinctively. My parents didn’t teach me that many painting or drawing techniques, but there were a lot of things in my environment that influenced me indirectly, or latently.

Beyond the visual arts, my parents had a broad appreciation for culture in many forms (musical, literary, cinematic, culinary, etc). They exposed me to some pretty unusual things as a young child, like Quay Brothers films, that helped form my imagination. Before I could read, I remember being fascinated by art books – in particular, reproductions of Goya’s Los Caprichos. It was on the bottom shelf of one of their large bookcases and I would always take it out and marvel at it.

LG: What was art school like for you?

Kathleen Hall: Even though the visual arts were a big part of my life growing up, I chose not to go to a traditional art school. I had a liberal arts education at the University of Virginia and didn’t really focus on painting until my senior year when I joined an honors program. Though I had been drawing my whole life, I did not understand much about how to use paint or color at that time. I was the only person in my program trying to make paintings, so it was a bit isolating. Luckily I had the wonderful painter Philip Geiger as my advisor. Around the same time, I also attended a Drawing Marathon at the New York Studio School, which was only two weeks long but had an impact on me and gave me a taste of that art school experience.

After graduating, I needed to see if I was self-motivated enough to make paintings on my own, outside of an academic environment. I moved back to my hometown of Columbus for three months and studied informally with the painter Neil Riley, who is also a close family friend. Another close friend of my parents, Anita Dawson, let me work in her studio while she was abroad, and I made a small body of work that felt personal and gave me some direction. I am very grateful to them both for that brief but important experience.

After that, I moved to NYC and worked as a studio assistant while applying to graduate school. In contrast to my undergraduate experience, I chose an MFA program that was exclusively painting-focused: tiny, only 4 students in each cohort, all painters. UNH offered me an excellent scholarship, so I went. The studios were spacious and light-filled and it was a good place to get work done. I also got to go to Italy over the summer as a perk of the program. The three other women in my cohort are good friends and wonderful, supportive people.

LG: Was getting started as a painter hard for you in your first few years after getting out of school?

Kathleen Hall: I think of the years following my MFA as my vagabond years (to be honest, I’m not totally out of them yet!) I was lucky to have a residency lined up right after graduating, so I was able to keep some momentum going and slightly postpone my return to the outside world. The years that followed were spent on a combination of short-term teaching gigs, artist residencies, and travel. I was also in and out of New York City, where my partner lived at that time. There was a lot of excitement during this period but having to change studios so often was disruptive to a sense of continuity in my work.

The good thing about working in less-than-ideal conditions is that it makes you adaptable. I have grown accustomed to working in small spaces, for instance, and making do with minimal equipment.

LG: What artists do you most often draw inspiration from in your work?

Kathleen Hall: I’m very omnivorous and like looking at a lot of different kinds of art, but some sources I return to are Edouard Vuillard, Georges Braque, Howard Hodgkin, Fayum portraiture, as well as a lot of medieval art. I also always find myself lingering over Degas. There is a kind of radical weirdness to his paintings, despite his technical virtuosity.

There are so many good contemporary painters out there, it can be overwhelming to try and sort through them. There are a few that have really stood out to me when viewing the work in person. I remember being blown away by an exhibition of Ann Gale’s work a few years ago in Charlottesville – her sense of color especially. I love looking at Lennart Anderson’s paintings in person as well. I saw the recent exhibition at the New York Studio School and tried to commit as much as I could to memory. Subtle, quiet paintings don’t tend to reproduce well, but that’s what I’m usually drawn to.

LG: How important is working from observation to your process?

Kathleen Hall: When I’m oil painting, I almost always paint from direct observation. I rarely use photographic sources. I’m not ideologically opposed to it, but for me, there is too little information contained within a photograph, especially regarding color, to hold my interest. Direct observation, with all its complexity and instability, gives me energy and a sense of urgency.

I do use photographic sources and reproductions for my gouache paintings. The scale of them (tiny) and the paint application (loose) keep me from being too literal.

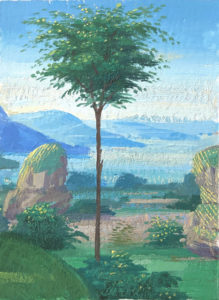

LG: Your gouache on paper works in the Folio section of your website is noticeably different in style and subject matter from your oil paintings. Can you tell us something about what led you to paint these?

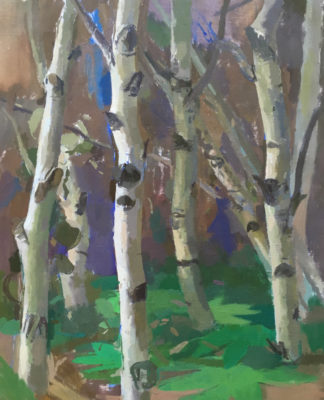

Kathleen Hall: At the onset of the pandemic in 2020, I was feeling restless and stuck in the studio. Spending time in nature was very important to my mental well-being at that time; I remember this beautiful spring unfolding just as the human world was becoming so chaotic. I don’t consider myself a landscape painter, but I started making these tiny paintings of trees. They are not expansive landscapes but more like glimpses seen through a very small window.

The trees are based on examples found in illuminated manuscripts. I have been enamored with miniature painting for years. It started with the 15th-century Northern European manuscript painting, Jean Fouquet and the Limbourg Brothers, introduced to me when I was in graduate school. When I lived in New York, I also spent a lot of time visiting the manuscript paintings in the Islamic Wing of the Met. During the pandemic, with museums shut down, I was engaging with these works through books and digital reproduction. I would take small background details (often low-resolution or blurred in reproduction) and make compositions out of them. Some of the trees I copy more literally; others are edited or amalgamated. They appear stylistically different from my other work because they are kind of a catalogue of different styles and iconography that I find compelling.

Part of what appeals to me about these works is that some of the techniques are so different and even antithetical to those I was taught in regards to oil painting, for example: working very methodically, from background to foreground, as opposed to working the whole painting at once. Of course, not being trained in miniaturism myself, I can only guess at the techniques employed in their making; I am not trying to replicate them per se. I use gouache very opaquely, so they are more painterly and less detailed than my source material. The authors of those highly refined works I’m referencing are often lost to history and remain anonymous, or they were completed by multiple hands, so you don’t get caught up in the mystique of the individual artist. It’s interesting to look at how the visual lexicon of trees changes over time or doesn’t – sometimes a 15th-century tree feels like it could fit very convincingly into a Roman fresco, in Livia’s garden, for instance.

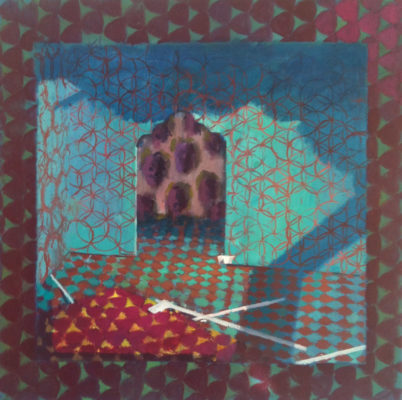

LG: Can you share some background and thoughts about what you are going after with your Small Worlds still lifes?

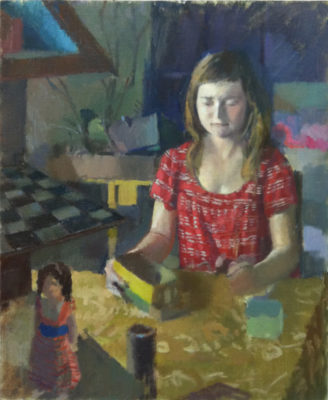

Kathleen Hall: I have been working on this series for years, and it has evolved much over that time. I always hesitate to label them as “still life” paintings, although some of them are more closely aligned with that tradition.

While in graduate school, I was using objects to create what were essentially tabletop dioramas, which I would then paint from life. At the time I used a lot of children’s toys to animate these worlds. Gradually I focused more on the spaces themselves and less about the characters and implied narrative. I shifted away from toys and more towards found objects, often from nature. These days, I am interested in creating setups that combine elements of terrestrial and aquatic, natural and manmade environments. I think of them as existing between still life and landscape. Sometimes I deliberately keep the identity of the forms more ambiguous or abstract – I don’t want it to become too much about rendering objects.

LG: How do you decide on what you’re going to paint?

Kathleen Hall:

I used to restrict myself much more in terms of subjects out of a desire for cohesion. For example, I avoided painting the figure for many years, because I wasn’t sure how it would fit in with my “regular” work. Over time I started to feel that I was missing out, and perhaps my work was suffering, by not exploring a broader range of interests. So now I give myself more permission to paint what I want and switch between media and subjects.

A lot of inspiration comes from observation in my daily life – walking in nature and picking things up off the ground, for instance. Sometimes I am just struck by an object, and wonder how it could translate into paint. I am always observing relationships and gathering information I might be able to use later. Sometimes the impetus comes from another painting, a color harmony that I want to borrow, for instance.

LG: How do you start a new painting? Would you mind telling us something about your process of making a painting?

Kathleen Hall: I don’t have a set method for making an oil painting. I usually cover the white of the canvas as quickly as possible, make a big mess, and gradually try to find some clarity. Though I do preparatory sketches, I often abandon that initial idea once I get into the painting. There is a lot of metamorphoses that take place, building up and scraping down; I tend to paint and repaint the same areas until I find something interesting or surprising that I can hang onto.

Sometimes they come together relatively quickly and other times they take many months to crack. The hard part for me is knowing when to stop – that sweet spot where it’s neither underworked nor overworked is so elusive. When I am uncertain of my next move, I like to let the painting “rest” for a while in the studio and move on to something else. That critical distance is very important to me. Then I feel less precious about going in and making a drastic change when I finally come back to it. I usually have several paintings going at once, for this reason.

LG: What are some of the concerns you care most about in determining the success of one of your paintings?

Kathleen Hall: I think I’m always looking for something unfamiliar (to myself) that comes from a physical engagement with the materials. But that alone isn’t enough, of course – I want it to be balanced and cohesive. That makes the unfamiliar more potent, I think.

I listen to music a lot when I work, so I could borrow a musical metaphor to describe what I’m searching for: a fugue has many interdependent parts that are like puzzle pieces that fit together in complete harmony. A great painting is like that too. Trying to get the pieces to lock into place is what is so exhilarating and frustrating about painting. At the same time, the painting needs to transcend its structure; the end product must be more than the sum of these parts. There should be a feeling of spontaneity or inevitability that belies the hard work. Although I appreciate one-shot paintings and am super envious of people who can do them, I tend to gravitate towards paintings that are more layered. Of course, in my own work, it can easily devolve into a kind of frenzy of endless revisions, so I have to be careful that way. Recently I have been making a deliberate effort not to overwork my paintings – to stop before I kill them!

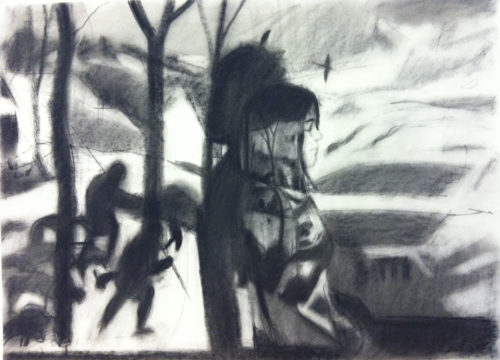

LG: Your large charcoal drawings are intriguing to me. Is this something you make regularly? Edwin Dickinson’s drawings come to mind with many of these. What can you tell us about your drawings?

Kathleen Hall: I don’t draw with charcoal nearly as much as I’d like to – it is something I tend to do when I’m struggling to find time to paint, or when I want to test out ideas. Some subjects that are more fleeting, like dappled light on trees, lend themselves better to drawing for me. I hardly ever exhibit my drawings or feel like they’re fully resolved.

I’m fond of the subtractive charcoal method with a toned ground, as I think drawing with the kneaded eraser approximates the language of painting a bit more. My paintings tend to be more weighted towards the middle-value range, so I like starting with that middle ground and pushing out towards the extremes.

Drawing from the figure is something I do periodically in the company of other artists or alongside students, or when friends come to visit. I wish I had the opportunity to do it more often.

LG: Do you ever wish to convey any non-visual components to your work, such as feelings about spirituality, politics, or emotional concerns?

Kathleen Hall: I never thought of myself as a strictly formalist painter, but I am also not explicit in telling people how to interpret my work. There is usually personal meaning embedded in the paintings, but that meaning can also change over the course of making it. In general, I try to avoid becoming too attached to the concept because it can hinder the process of discovery and experimentation, in my experience.

I think still life painting, in particular, lends itself so strongly to narrative – even supposedly neutral objects like boxes can be powerfully suggestive. I don’t avoid objects that are loaded with associations. For instance, lately I am interested in painting coral because it attracts me visually, but it’s impossible to use it as a subject and not think about its precarious existence in the world. It’s a very traditional still life object, but it’s different painting coral in 2021 than in the 17th century. It feels a bit like an elegy sometimes. However, I think there is always something inherently hopeful about painting because it helps you reimagine the world.

LG: Painters often don’t get many rewards or attention for their artwork. Many work in isolation, which can be a fertile ground for destructive thoughts like self-doubt and worry to grow. Antidotal here-say suggests the current percentage of painters who stop painting a year or two out of art school is very high.

LG: What helps keep you moving forward with your art? Would you have any advice to offer a painter who is feeling depressed about all the difficulties of being a painter?

Kathleen Hall: I hesitate to give advice as I definitely do not have it all figured out myself. For so many of us, there is a lot of precarity, a lot of uncertainty. In this country, there are powerful economic barriers for most people to sustain a career in the arts. It is important not to internalize whatever struggles you face as a referendum on your worth as a creative person.

Ultimately painting, or any creative pursuit is its own reward. We do it because it is necessary to our survival in some way. I think we need to remain connected to that part, to make work that is personal and meaningful, regardless of how marketable it is. To keep it going in some form, even if we aren’t able to make it to the studio every day.

There is a difference between solitude and isolation – the former being essential to making your work, and the latter being detrimental. We live in a highly individualistic society, which can take a toll on people’s mental health. Because I have moved so much in my adult life, it has not been easy to maintain the kind of close-knit peer group of artists locally that I had in graduate school. Artist residencies have helped to temporarily fill that void. Sharing the challenges and small triumphs of the studio over dinner or casual conversation, with people who make very different work than you, is very affirming. Those kinds of experiences can help sustain you in periods when everything seems bleak.

Really wonderful work. Thanks for posting.

I like all of it; but esp those small portraits and still lives.

I enjoyed ‘hearing’ Kathleen’s voice through reading her interview and learning about the evolving nature of her work and subjects and seeing many of her creations – a beautiful body of work. Where would we be without the creations of dedicated artists who continue their work through these last years of particularly challenging times. We look forward to seeing your exhibition in Richmond, VA.

Great to read, very much like having you talk in person! So helpful to hear how one painter copes this time of isolation.And I always admire the work.

This is lovely. Thanks so much for posting it.