I am pleased to present a new interview with Kathleen Dunn Jacobs, a distinguished artist whose multifaceted career has greatly enriched the art community. I first became acquainted with Kathleen through my helping make a website for her foundational work with the Blueway Art Alliance in Western Massachusetts and with her roles as the Marketing Director for the Concord Center for the Visual Arts and the former Director of the Currier Museum Art School in New Hampshire. Kathleen resides in central New Hampshire with her family. She holds a BFA in painting and art history from the University of Massachusetts and an MFA in Painting and Visual Studies from Lesley College of Art and Design. Her paintings and drawings focus primarily on working from life, especially the landscape but also she also creates studio inventions and experimentation. Her brilliant, lusciously rich palettes and expressive paint application explore the landscape through abstraction, challenging traditional academic frameworks to craft a unique and rich visual narrative of poetic expression. Kathleen also teaches painting and drawing workshops across the United States and abroad, including in Ireland and Italy.

Larry Groff: What led you to want to become a painter?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: My first drawing class in college strengthened my desire to be an artist. Drawing opened a floodgate of emotion and drive to express myself with art. I was raised in a family that honored creativity and art, and I feel fortunate to have been able to easily follow my passion.

LG: What was art school like for you?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: I loved both my undergrad and graduate school experience, having found my tribe and support system. I developed meaningful, lifelong friendships from that time in my life. I was encouraged and treated with great consideration to help find my artistic way. My first drawing teachers pointed out what was interesting about each student’s work, but with a sense of excitement that motivated all of us to work hard and look forward to each assignment.

LG: What were some of your most important lessons from that time?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: To this day, I model my teaching after my first drawing teacher’s method; that is to give thoughtful, honest and constructive critiques with a very kind, yet serious tone of encouragement. The most important thing I learned was to stay true to myself, and to see and draw by getting deeply involved with what I was looking at, no matter what the subject.

I learned to draw from piles of junk piled in the middle of the room and as I made marks with charcoal on big pieces of paper, not as a slave to replication but to understanding space, form, and structure within a composition. Drawing became a way for me to be involved in the world around me and a way to stay honest with my work and live in the moment. I learned not to intellectualize the act of drawing but just draw what I was seeing. I learned to get lost in seeing and let go of my expectations. The ordinary, everyday world became an interesting place for me, and I believed that careful consideration given to seeing can make a drawing or a painting exciting, no matter what you are looking at. I learned how to remove the chance of making work that is preconceived and let my process take over to see what will happen. It was and still is an exhilarating practice for me.

LG: Can you say something about how the transitioning from work done outside life to indoor work from memory or outdoor studies impacted your relationship with the landscape you’re portraying? Would you say that you also bring the studio’s sensibilities back to your work outdoors?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: To begin my painting process, it is necessary for me to look at nature directly, keep one foot on the ground, and remain connected to the source of what I believe is real and what is precious. My paintings, process, and perception of my artistic practice have evolved. and lead to many questions driving my entire body of work. I love working outdoors since it helps me express my feelings about a place. Nature is a great teacher, and being outdoors keeps me out of my own head since I love to get lost in what I see and feel. And I love being outside. To this day, the work I’ve made directly from life outdoors—whether on Cape Cod, Italy, Ireland, or New Hampshire—are the most exciting paintings for me, they seem the freshest, and feel the most honest and the least self-conscious.

My studio work is more a reflection of my internal landscape, but it always starts with work that I’ve done outdoors. And I never replicate paintings. My studio work can sometimes be compilations of places, made-up places, and sometimes very specific, real places that I know well. I will often just use the colors and shapes in a different configuration that feels like a landscape but is not a literal depiction. I love working from memory now—something I thought I’d never be able to do when I was younger—and I incorporate a memory that is based on how I felt in a specific place.

I am deeply interested in how space and place affect us and how the variation or the simplification of space or shapes within a painting changes how we feel. A slight change can shift how it makes us anxious or calm. My constant preoccupation is deciphering and trying to understand what I’m looking at and why a space or place makes us calm. I try to just work and analyze after. That feeling of calm, both in my direct outdoor observational work and in my more distilled studio work, seems to just happen without trying. I credit that to getting lost and not analyzing until I finish a work.

Both painting practices, whether working from life or working from those paintings I’ve made outdoors, inform one another. I specifically love that about painting: that there are infinite ways to make a painting because of the infinite combinations and relationships that can be made. I like the idea of knowing that everything is related and that the colors and shapes depict relationships on a canvas and, in the end, can result in an interpretation of many human feelings that we all experience.

LG: I understand you worked with Maureen Gallace for a time. What piece of advice did she offer that made a difference for you?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: I worked with Maureen Gallace in graduate school. I wanted to work with her because I saw her small, buttery, postmodern landscape paintings at the 1998 Whitney Biennial. I loved that she was upholding the tradition of small landscape painting, as I was trying to do. Her work is highly influenced by the work of Alex Katz, and I loved the way she physically placed paint on the surface that resulted in a buttery appearance, like thin frosting with minimal information from minimal compositional elements. She helped me develop my studio practice—my work that is removed from the natural landscape and, hence, work that is more internally derived. I have a love of American post-WWII modernism that she relates to, as well, so I was thrilled to work with her. She is completely committed to her vision, which I respect.

I also worked with Barry Schwabsky, an advisor for a semester in graduate school. He is the art editor for The Nation and a brilliant poet who thinks like a painter. He writes about contemporary art and all the most relevant artists in the world today. His observation of my work became pivotal for me. He confirmed that my ambition to make work about the landscape/nature was relevant when few noted contemporary artists were painting the landscape from life or in person. He pushed me to dig deeper into understanding the work of Corot, Cezanne, and other more contemporary artists like Gerhardt Richter, Peter Doig, David Hockney, and many others—so as to understand how I fit in with my work in the context of our time. He confirmed my belief that art should be for others and is not a selfish act. That was a concept I have always tried to live by. I strongly believe that art is necessary and important for everyone in our society.

LG: Your work includes both large and small-scale paintings. How do you see these differing scales talking to each other when seen together as a whole body of work? Or are they separate activities?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: It’s all the same body of work, and I face the same issues, no matter the size of the painting. I love composition and have studied the compositions of paintings by many of the masters of painting: Rembrandt, Cezanne, Morandi. Mostly because their love of composition and structure interests me in the same way. Composition became the underpinning for my painting mantra. Looking to nature helps me to compose naturally and keeps me from making contrived compositions and creating original work.

LG: You describe your works as ‘reconstructed landscapes.’ Can you elaborate on how this concept guides your creative process, particularly in what you’ve called “balancing the elements of tranquility and chaos”?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: My reconstructed landscape paintings are just one body of work of mine that is informed by my observational body of work. I started making reconstructed works without knowing what I was doing. I began rearranging the formal elements of color, forming space into completely different compositions while keeping the same tonal color relationships. I randomly rearrange elements, pushing and pulling them into something that I hope is graceful and calm while thinking of the space I was painting from life for my other representational paintings. My process can sometimes seem chaotic, but somehow, I eventually land so they feel more tranquil than chaotic.

My reconstructed landscapes reference the outdoor spaces I’ve painted, and they rely on my memory of the feeling there. Feeling from color started to come to the forefront instead of a specific place as the subject. My paintings became abstracted spaces as I pushed toward a greater point of distillation of the elements within my compositions.

LG: Your painting process involves ‘layering, editing, deciphering, and rebuilding.’ Could you walk us through a specific example of how this process unfolded in one of your recent works?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: In Great Island Brush Woods (see figure 13), I layered, distilled, and reconstructed the organic shapes from my original painted sketch to create a new composite image of the natural landscape. I’ve spent many years outside on Great Island in Wellfleet and have many memories and painted records of its muted green woodland. I used a vertical format—in contrast to the usual horizontal format found most often in landscape paintings—to help indicate that I am looking to nature anew, since we can no longer take its vitality (nor its very presence) for granted.

When I look at a landscape, that perceptual moment is when I gather information, not only about what I see, but my own emotion that can come only from looking … from witnessing my subject in person.

As I progressed, I pushed my paintings to an even greater point of distillation, as in Cahoon’s Edge , reducing my compositions to eliminate any obvious signs of a tree, field, or conventional horizon line.

LG: Your work reflects a response to the rapidly changing landscape due to factors like climate change and development. How much does portraying the beauty of nature stand up to the urgency of these environmental issues?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: It’s fair to say that my paintings contain layered meaning. Minimally, my paintings are a reaction to the Western culture of my time—my rejection of our society’s penchant for excess and indifference that threatens our planet’s ecosystems. I do not paint pictures of polluted rivers or littered fields. My work represents my own attempts in these chaotic times to reconnect and to decipher the natural world, and to come to grips with the exigencies of today’s stark environmental situation.

Violence and destruction exist in nature, yet when I paint, I choose to ignore these traits. In nature’s predictable rhythmic patterns, I see the sublime. To me, nature represents the ultimate example of gracious acceptance of change, even death; winter’s repose inevitably yields to spring’s rebirth. For these reasons, my paintings, at least, are simplified, idealized attempts that speak to nature’s persistence, vulnerability, and beauty, which I paint if for no other reason than this: within the natural world exists the promise of rejuvenation.

LG: You mention being influenced by the play of saturated colors with tonally mixed neutrals. How do you decide on the color palette for a particular piece, and what role does it play in your work?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: Nature is where I find my color palette and is what inspires me to keep looking and deciphering color. I use a very limited painting color palette, sticking to a warm and cool of red, yellow, and blue, and make any color I see with those three colors. I must keep it simple since it is such a very complicated endeavor to untangle what is in front of me. I am interested in making the colors I see, which, in the end, makes the paintings feel calm, which is why I am in that landscape. It all circles around, it seems and is all hindsight now; after years of just making paintings because I love to be outside, I realize that it calls me to be there to record. I fear losing our natural world, so I record it as best I can through my personal lens.

LG: Can you say something about how Giorgio Morandi might influence your work? What other painters have been most central to you?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: In formal matters of painting, Georgio Morandi would come to influence me largely because of his emphasis on close tonal colors and compositional structure. Morandi’s Landscapes are all about the structure of the landscape and his own honest, observational interpretation.

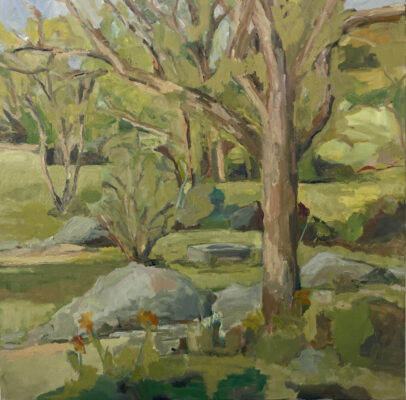

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: Like Morandi, I see a combination of randomness and pattern in the landscape, and I seek to portray both. In Tree/Bush Study, my intent was to divide and interpret space. I established simple shapes of flattened mass. Deep space was not my concern, but space within the flat picture plane was, with the positive shapes filled in with closely related tones of color to portray serenity and structure. Tree/Bush Study combines abstracted form with the natural pattern, sequence, and order I see. This is what Morandi accentuated in his paintings, and why I relate to his work.

LG: You’ve expressed a lack of interest in replicating reality as a camera would see it. What grabs you instead? What aspect of reality is the most interesting thing to try to get at in a motif?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: Nothing can be replicated, and paintings are one personal take on the world. Art represents optimism for me since it is a synthesis of a personal vision and experience that creates another experience for the viewer. The idea of the unknown is what is thrilling every time I make a painting, no matter what I paint. I like the unpredictability of what will be made, that becomes new reality. I don’t think about a motif; I just search for a place I like and try to paint it.

LG: Having taught painting and drawing in various settings, how has your teaching experience influenced your own artistic practice?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: Teaching has made me realize how thirsty people are for an authentic experience, and painting provides that authenticity, as well as an authentic expression of a moment. Teaching has made me want to keep painting —especially from the natural world that is consistently challenging. I’ve seen painting transform people into artists after spending one week outdoors. It’s a magical and wonderful privilege to travel, teach painting, and especially to paint for others to enjoy.

LG: Looking back at your artistic journey, how do you feel your work has evolved, and what future directions or explorations are you excited about pursuing?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: I never tire of painting the landscape. I recently moved to New Hampshire, away from a lifetime of painting on Cape Cod. The challenge of embracing a new, lushly vegetated landscape without having lived very long there, is a new and great challenge. I’m interested in seeing how my work will continue to change now, and I believe it’s only through the process that I’ll discover that. Lately, I’ve been interested in trees, in dense forests. I am also interested in how water has been a consistent player in my landscapes, from looking at the ocean to now looking at meandering rivers. I am excited about pursuing that thread for now. Certain themes seem to stay within my work, specifically depicting natural space, and specifically depicting water. I try not to think about it too much, knowing I need to just paint and see where it goes after looking at them.

LG: Can you say something about the workshops you lead here and abroad? What might a potential student expect to learn and experience from your teachings?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: I have landscape painting workshops at my farm in Contoocook, New Hampshire, and travel to Ireland and Italy each year to teach 10-day workshops. This fall, I’ll teach a workshop to Vinalhaven, Maine, a rare “step back in time” place that is an island off the coast of Rockland, Maine.

LG: My workshops emphasize the idea of sinking into a place. I teach my process of painting, which includes how to decipher complex natural settings, but my students and I also visit galleries, art museums, and cultural sites.

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: An important question I like to pose to my students early on is to ask why they are painting. I don’t expect answers, but I talk about how important the intention is behind their work, since it is perhaps one of the most important components for making a painting. I like to focus on the bigger picture of intention so that each student will grow. I believe that intention will inherently come out as they work, and they will learn to make more interesting paintings for others to look at.

I also teach my method of simplifying the landscape. I don’t teach formulaic compositions or ideas and, in fact, purposely stay away from that when I teach. It’s often not what students expect, but, in the end, they develop their own way of seeing and, therefore, create paintings that are less contrived and more exciting.

LG: What art book do you treasure most?

Kathleen Dunn Jacobs: Oddly enough, I treasure most books by the Irish philosopher and writer John O’Donohue I read his work repeatedly to develop my relationship with nature and life and to develop my personal intention of painting landscapes. His books have helped me understand my painting in a way that feels authentic and keeps me positive and appreciative of the natural world that, seems to me, is becoming more and more angry these days.

The artworks showcased here are absolutely beautiful. Kathleen mentioned she got inspiration from her first drawing class.

I recommend every artist learn to draw and draw well. It’s an essential skill for continuing creativity in any medium.