I am pleased to share this email interview with the painter Karen Kaapcke. I had been following her work posted on Facebook and was intrigued by her composition and the way she combined her classical trained background with abstract visual concerns. At the same time, using the power of painting to respond to personal and societal concerns. She thoughtfully speaks at length about her work and process as well as discussing important considerations about the abilities of painting to respond to our many connections to the human condition.

Karen Kaapcke studied painting at the Art Students League of NY as well as the National Academy of Design School of Fine Art, NYC. She has exhibited widely in New York and across the country since 1995. In 2019 she was one of nine artists from the United States selected to exhibit at the prestigious BP Portrait Award, In 2012 she won First Place, Portrait Society of America: Self Portrait. She has won a number of other awards and has had numerous articles written about her work.

Larry Groff: How did you get your start as a painter and what artists or teachings influenced you most as a young artist?

Karen Kaapcke: I began seriously drawing while working on my Masters in Philosophy. While experiencing “writer’s block” for the first time, I went down to the lower level of the building that my office was in for a break, and that was also where the Fine Arts Library was located. I walked up to the sculpture section, and pulled out a book on Donatello, and was stunned. I found Michelangelo, Rodin, and others and I checked them out and began copying them. My “writer’s block” wasn’t that I couldn’t write anything – but rather that everything I wrote felt wrong. But this felt right. It seemed that these artists were saying what I was trying to formulate in words but that was, I suddenly saw, possibly beyond words. The rest of the year was quite difficult – I really felt I had to change my life completely in order to make sense of all this, but I did manage to finish my work and complete my degree.

I knew that I needed to study and thoroughly learn this new ‘language’ for lack of a better word. I had heard about the Art Students League in NYC, that it was this kind of place where you could put together your study independently – but with what I heard were great teachers, and because I had to earn my living at the same time I figured this could work out. I was also quite done with anything ‘academic’ – I was done with the university system. And so I began as a sculptor there, and worked very closely with Barney Hodes, even cleaning out the studio that he shared with his monitor in Brooklyn, in exchange for time working there from their model. After a year or so on a waiting list, I got into a drawing class taught by Ted Seth Jacobs, and then finally his painting class. When I started painting – it seems that it was when I first even just looked at the palette he suggested using (a very extended palette), I felt that color opened up an entire universe. It was thrilling! When I told this to Barney he said, with that sentiment you are meant to be a painter.

Apart from those initial encounters with the sculptors I mentioned above, I spent a lot of my time while studying roaming the city, and searching for work that spoke to me. DaVinci is always an absolute support, instruction, and inspiration, then and now. I strongly remember loving both Susan Rothenberg and the Dutch Masters at the Met. I consumed Rembrandt, and yet also loved all the work by Robert Ryman and Agnes Martin I was seeing. I was voracious but not indiscriminate; I was searching for what seemed to me the best of it all, every way of making paintings. One contemporary painter who stood out for me was Sydney Goodman – I stumbled upon a show of his work at ACA Gallery; I kept looking for more of his work but it wasn’t shown again very often. I remember I had to find a new apartment at that time, and I very nearly moved to Philadelphia to study with him at PAFA, but then I found an affordable place in NYC and that determined my path to some extent.

LG: Many of your earlier works embraced more traditional realist approaches concerning such things as drawing and modeling form. What are some of the most important changes your art has gone through over the years?

Karen Kaapcke: Towards the tail end of my work with Jacobs, in the early 90’s, I began painting abstractly – really trying to figure out what can be done with paint and color. What are the limits; what happens when this color sits next to that, or when a line draws all the way to the edge of a canvas as opposed to when it stops a few inches in. I was beginning to expand my language and for a few years I was only doing abstract painting. That was the first big shift.

Around the mid-’90s however I took a trip to Madrid to visit the Prado and seeing the Velazquez paintings, and the Goya paintings really shook me up. Upon my return, I recommitted to figurative work. But it wasn’t enough. I felt limited and again, that what I was saying was not right, was not what I was trying to say. Not that I knew yet what that was; I did know though, just as when I was in the Philosophy program, that the language wasn’t mine yet. I began to think in terms of breaking down barriers, bending rules, really doing some serious play, but it all felt very much like I wasn’t quite ready yet – so I maintained a focus in a lot of my work on continuing to develop the elements of classical craft, often for long periods focusing entirely on modeling light and form, on studying anatomy.

At each phase, whether painting abstractly or representationally, I was fully committed to it and felt that this was what I was supposed to be doing. I never viewed what I was doing as being on the way to anything else. It was not easy as the art world, more so back then, seemed very divided into ‘camps’, and nobody really had much patience or acceptance of folks on the ‘other side’. I often had small crises – I never felt at ease and was in a state of constant doubt for all my commitment.

There have been other moments that resulted in great shifts in my work. In the mid-90’s I was asked to make a painting to Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream for the Israel Orchestra, to use on posters and such. Listening to the music and attempting to make a painting to it – this became one of the first times I felt that the work I was making was in a language that was appropriate and personal. It was a Bacchus-type figure, in a field of masses of paint barely resembling leaves, with a kind of leer. It seemed to me that making the music the priority and allowing my work to respond to the music, gave me a kind of liberty – from maybe conventional painting rules, but not from rules in general. This was probably the beginning of my understanding that the painting itself determines the rules.

Another moment that was critical in terms of how I work now, was when a boy who was my son’s dear friend suddenly died in an accident. He lived in France – and while we were on the airplane on the way home from the memorial service and cremation, I started to ask myself both how can I possibly paint after this and also how can I possibly parent my son through this. It came to me that I needed to paint this boy; as a painter it felt almost required of me, even if I never painted anything else. When I got home I began a series of works from memory of him, and of him and my son together. What I ended up painting was a series of the two of them on a new journey of sorts. I discovered – in fact, was kind of blindsided by this – that by working from memory and imagination I had the full range of visual language available to me. I had the freedom to use imagery that became personally symbolic: the raft or boat, dark feathers, water. I had the freedom – because it was the sense of this boy, of these boys, that was more important than the painting as a “picture”- freedom to use and paint anything. But it was also clear to me that this freedom was only possible because of my years of absorption in the figure and in the development of certain skills pertaining to being able to render what I was seeing – this time though not observationally in the usual sense, but based on what I was observing in my mind’s eye.

This movement away from working observationally, from what you might call “objective reality”, towards working in a way that I sometimes refer to as observationally from my mind’s eye, released me from many obligations. I was no longer obliged to paint anything in any specific way. But all in the service of a larger something – nothing is random, and the job was from then on to become sensitive to the logic inherent in each painting as it comes into being. Of course one is never under any obligation, but I have found that when working strictly from a model, say, one is – as one should be – dominated by the model, or by what is present. As difficult as it is to paint what one is seeing, it is also very difficult to deviate from it.

LG: What are the most important differences between what you’re concerned with now and what you did before?

Karen Kaapcke: In the period of painting after the work I did around our young friend who died, I became increasingly more aware of the relationship between painting and what is NOT there. That in painting, you are making something visible, not just re-presenting what is. While this may seem obvious (even the most strictly representational painters bring something wholly new to light), the sense that I was literally giving voice to what had, until then, not been articulated was a pretty radical thought for me. I no longer had the burden of finding the right subject, but there were new dilemmas. How do you know what you are giving voice to? How do you hear something that is silent? And other problems – how do you know if something is ‘right’ if you have no parameters, no measure? How do you begin? How do you end?

Once this was opened up though I noticed that when I sat down to paint, without any real preconception of what to paint, I became increasingly more open to everything and much more susceptible. Some deeply personal things, yes – but also I felt that the emotions I was working with were very linked up with things that were happening in the world. I don’t really like the “objective/subjective” distinction – I find it a false distinction – and I think painting can show us precisely that. If you are painting some deeply personal, emotional stuff honestly, I think it is no longer ‘personal’, it becomes about something like the human condition or even more. I think the best paintings, look at Rembrandt, what he gives to us in his self-portraits – are those where such distinctions break down.

So now, I start painting and then ask all these questions of the painting. What is this line that is tilted up to the right telling me – is it a figure leaning? And if so, why? Is it looking down or up?

And suddenly I’m in the possible narrative and open to what it may be. It may start out quite intimate to me and my small realm but then grow larger as they are not really ‘me’, they are drawings of a state of being, or it might pertain to the large scale oppression we may all be feeling currently but which then can feel deeply personal – as in a very new piece, Virgil’s Lantern.

And many things in between. Working from memory and imagination, you lose this distinction of what’s ‘in there’ and ‘out there’ with the painting. This is completely different from how I previously worked. Though I feel it was the years of working abstractly that gave me an idea of what it is like to work without any parameters of rightness, without any measure other than the painting itself, So I do see the roots and connection.

The other thing which is related is that I began to see the things of the world – and most importantly for me, bodies – as having a metaphorical dimension that parallels their more down-to-earth meanings. But also that this metaphorical dimension is not given – it is yours to make. Everything is both itself and a metaphor. So these are all the things that help guide the painting: if the arm is not functioning in terms of the metaphorical reality, it might need to go. Maybe the orange round things are actually clementines or some sort of fruit and not something inanimate like marbles and then it clicks, the necessity of having the life and ripeness of what is possibly fruit in the painting. So also this is not a verbal metaphor. It is meaningful visually and experientially.

Self Portrait with Palette, oil on linen, 50 x 64 inches, 2008

LG: How important has observation been to your work?

Karen Kaapcke: My initial training was extremely observational. Both in painting/drawing and sculpture. The goal that I embraced was to attempt to rid oneself of preconceptions bit by bit and come to see the visual world more and more ‘as it is’, and respond to that. A worthy goal even if unattainable. This training was extraordinary for me, even as it showed me in the end how we are never free of preconceptions. There is enormous value however in becoming aware of your preconceptions; even in just becoming aware that you have them. There is then that moment of hesitation before the observed world.

I would say that even in my work from imagination and memory, which is how I now mainly work, what I am doing is observing what I see in my mind’s eye. I have seen a leg uncountably many times – and if I can hold the image of the leg doing what I want it to do in my mind strongly enough I am in a way observing it, and then can paint or draw it. There are varying degrees of observation in any given painting; and lately, within the past few years, I’ve been working with figures such that a model certainly couldn’t hold the pose – even for the duration of a photograph. By the way, I do not work from photographs, but mainly because I am interested in what happens when I deviate from working from life, what that freedom brings, not in replicating a pose but in exploring what happens when I use the figure as a malleable element in a painting.

LG: How do you start a new painting? Please tell us something about how you go about making your art? What are the most critical parts of your process? At what point do you decide to stop working on a painting?

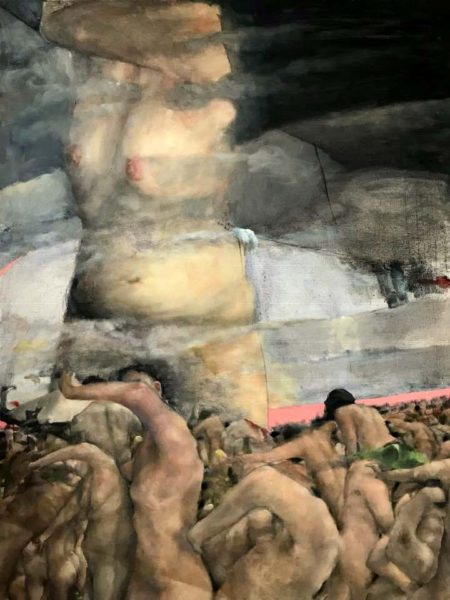

Karen Kaapcke: I don’t really have a specific way of beginning. Right now I am doing a series of paintings that I am calling Stasis for now. I am starting from a heavily chromatically toned canvas so that I have this to springboard off from. It also gives me right away something to think about in terms of meaning. In the group I just finished there is a rough red/white/blue toning for each of the three paintings, though it is actually red, dirty Naples yellow, and blue-grey – but this is important as each piece became a particular part in a cycle of a kind of American struggle without the literal red/white/blue announcing itself. Although now I’m in the middle of a green one – so I think the narrative has shifted.

I began this particular way of working by wondering how I was going to start a specific piece earlier this year. As I was out running one morning I thought of the Australian fires which were then raging, and an image that I had seen somewhere came to me – of the rush of the firewall moving with such speed and just consuming everything in its path. So I decided to paint the entire canvas a deep powerful red and begin from there. What I did next is what I often do even if the canvas is not toned: I began to draw with charcoal, loose broad strokes or quite literally whatever occurs to me – draw first, ask questions later. I find my figures in the gestural lines and I work them out, keeping some and discarding others, all the while asking what I am doing this for. What is this figure doing, what is this line and shape? If I don’t know yet, I continue to work developing the figures and just hold the question in my mind, often all day – as I’m making dinner and so on, asking myself who this figure is. Soon a light source emerges and with that a bit more of what’s going on. Usually, I’m moved to start applying paint when I feel the need for light, or that the figures are kind of crying out for that kind of development.

There are always surprises along the way – I might suddenly visualize a figure and develop it and then see in a flash that what is happening is not at all what I had at first thought. Those are great moments – I would say critical moments, that tend to happen when I get into a good flow with a piece. It’s the least comfortable moment in painting; often you have to get rid of aspects of it that maybe you really liked. In this painting that started with thoughts about the Australian wildfires I had a moment in the painting where the climb of figures – what they were climbing towards – became clear to me as I saw in my mind the scales of justice being held by the top figure. I painted that in and that finished the painting. It changed it completely and finished it at the same time. So that is a bit of an answer to your question about when to stop a piece. It’s usually quite unclear. I always think I’m finished before I am. But the painting kind of haunts me, doesn’t leave me alone and then there is really one thing or moment of discovery that’s missing. I leave the pieces hanging around the studio for days just looking at them sideways, not really mulling it over but just holding the image in my mind – and almost always I am struck by something that clarifies and completes the painting. But this is very important – it is a moment when the meaning gels, or that the narrative makes a kind of sudden sense to me.

It really always amazes me how when finished there is a sense of something like formality to the painting – that I recognize, and yet I have no idea how it got there. It just kind of suddenly has its own existence apart from me.

But this is just one way of working. I often paint over older paintings (when I’m in the mood to get rid of pieces that I don’t like at all from an earlier time but to be economical and save on materials I don’t throw them out or burn them); or start right away with big washes of color. I have a slight portrait practice – every other week I paint a friend and fellow painter from life. The drawing/painting I am doing of him right now was begun on a wash of dark oil paint onto Arches oil paper and then drawing into that. After the session, I painted over it with a grey wash leaving some parts still visible, and the next session I started into it again, to engage again with the process of finding him. A lot of drawings I have also done from life in a way – but, I would work on them mainly during the breaks of the model. This is one way I developed being able to work from memory. I also practiced drawing reverse images from the live model – seeing it one way and drawing it the opposite (if a head was looking to the right, I’d draw it looking to the left). A lot of ways of trying to break one’s mind free from the dictates of observation, while still using the skills derived from working observationally.

LG: With your current works, how do you go about balancing the degree of abstraction and representation you want to have in the picture?

Karen Kaapcke: I am very committed to having all elements of the painting exist for reasons that are integral to the visual meaning of the work. I really don’t see much of a distinction between abstraction and representation; it is all a part of our visual language though of course using different skill sets.

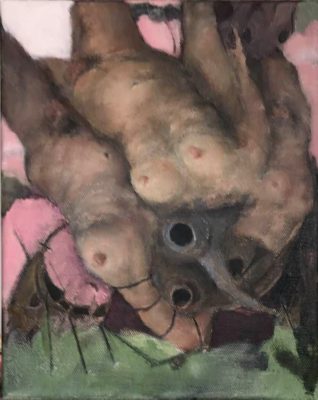

Whatever rules there are for this are unique to each piece and emerge as I work on a painting. So I may be going along rendering a figure reclining in a certain way, and as I work I feel a repetition of a certain kind of shape, like the dark rectangles in Salvage.

Without judgment, meaning without the idea that one shouldn’t just start painting in dark masses like that if doing a representational painting, I paint the masses in. I saw references to Ophelia and started working in greenery – growing around a bathtub that could then be outside as well? But then I do judge everything afterward – after making a mark it’s essential to look very hard at it and see if it leads the painting forward or seems irrelevant, or lifeless. In the case of the rectangles I saw that the rhythm of this repetition was important, and the greenery giving a tension between the wildness of the body and the domestic, tamed safe side. It’s a different kind of judgment than that of judging what kind of painting is allowed, or of mapping it against an existing reality.

There are moments when I may be painting very realistically, and then I see a meaning that is not at all literal. Or that the figuration is becoming way too literal and I start working against that – maybe by sanding down parts of it, or turning the piece on its side or upside down. I do feel a painting – no matter how representational – should somehow work when turned on all sides. I see new aspects of it this way – but I feel very strongly that nothing of this is random. I am very nearly finished with a painting that I may have completed by a feeling I had that the figures I was painting were somehow boxed in – and then I thought yes, they are boxed in by a kind of belief, and this is also their tragedy. And so I pushed them in a more abstract way into a box-like position relative to the rest of the painting, and I call it “God Box”

LG: What might cause one of your paintings to be a favorite?

Karen Kaapcke: I find that when working the way I do, and trying to be honest in my work, that there are many paintings that would be the opposite of favorites because they are hard for me to look at. But that is not a reason why I would decide they shouldn’t exist as paintings. I do though have a few where I feel I managed to actually paint what feels like the inside of my head. One of these, Quod Animatum Est, went very far beyond feeling personal at the same time. So I guess that would be it – when something manages to go deep enough that it touches upon a kind of universality. Also, I think I am particularly fond of paintings where they were on the edge of failure – if not outright failing, all while I was working on them, and their coming together amidst all this failure has a sense of surprise for me. There is one that I love that is still like that called Sleep/Hydra.

It’s on the wall by my front closet and so I see it a lot, and every time I see it I am surprised and I love that. To surprise oneself! That is almost why I paint.

LG: Do you ever return to older works and repaint them to better reflect what you’re concerned with now?

Karen Kaapcke: I paint onto a lot of older works but mainly when I try to cull my store of paintings, and see paintings that are really just clumsy steps along the way. I usually sand them down, but there can be parts that are still visible that I springboard off of. I really enjoy doing that. There are only two instances where I think I repainted works in a way I think you’re asking. There were two figure paintings, very academic, done in class when I was a student, and while they were fine enough and I didn’t have the urge to destroy them, they were just so boring and I was in the mood to see what I could do with them, where playing with them would take me. So I just went to town on them, and brought them to a place where I was addressing specific questions of what level of abstraction might work with that level of realism. I’m thinking of one called “L FIgure” in particular – I feel that those paintings were exercises in that particular problem, where I was working out a challenge of taking a very classically painted figure and integrating it with abstraction. It’s an important thing to practice, just as much as actually having painted the figures – to figure out what the underlying something is, or where it might be wanting to – or willing to – go. I use the word exercise but it is also like pure-play when I work that way. If I’m willing to burn the painting, why not try out all kinds of things on it. Now that I’m thinking about it, I also did this with a group of landscape paintings that were just sitting around the studio. They were sufficient, but that is all – and I wanted to see if I could find something else going on in the landscape. I called the group Landscape Play. One of them was just a tree, probably a tree study – and as I looked I saw it in snow, and a kind of rhythmic relationship to another tree – and then I played with the snow and painted in circular shapes that also repeat. So I took something that really was kind of boring, and used it to explore more current concerns.

LG: You made a series of paintings in 2017 with a theme of “Life’s Stages” where you collaborated with the pianist, Alan Moverman and performed at The National Opera Center, NYC in 2018. Can you tell us more about how this came about and what it meant to you?

Karen Kaapcke: An acquaintance who I had known for years, he is the father of a girl my daughter’s age and we met on an NYC playground and kept running into each other in the neighborhood – each time we’d talk for almost an hour it seemed. He’s a pianist for City Ballet and a composer, and we always seemed to be on the same page artistically. We kept talking about getting the girls together for a playdate but that never seemed to materialize. Then Facebook came about, and we were able to appreciate each other’s work that way and he was able to see my paintings instead of just having me talk about them. I had finished with a group of paintings – I think the paintings of my son and his friend who had died – and was feeling a real emptiness. Right about that time he messaged me and said that he often does private recitals, but that he had been thinking about doing a collaboration with another artist and he asked if I’d be interested – as it seemed we were already halfway there with our conversations. The timing was impeccable, too perfect to turn down.

He presented me with the idea of working to piano pieces that he was interested in performing. In general, his recitals tend to be around themes, and he suggested we work out a theme together as we discuss and play with the selections he provided. As soon as I listened to a recording of the first piece he suggested, Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No 32 Opus 111, I saw in my mind almost the entire painting and just started working, emailing him at some point that I had already started. We discussed what it was about this piece that made it so powerful – the fact among other things that it is an ‘end of life’ work. All of the pieces represented a particular stage in the life of the composer, and Alan and I talked at length about being at the stage in our own lives where this collaboration became possible.

What made this collaboration so timely was also that I had reached a point in my work where I was working mainly from imagination/memory, and I was very interested in the challenge of putting this to the task of visually interpreting music. And it had an interesting connection to that painting I had done a while ago – the Bacchus to the Midsummer Night’s Dream by Mendelssohn. I also have always had slight synaesthesia, in that, I would see color to live music (not recorded) – it had become my personal measure for when a performance was really good. What was fascinating to me though was that since menopause, I had stopped having this kind of synaesthesia and was kind of mourning that loss – but in listening to the recordings for this collaboration, I did get visual impressions which were itself odd in that they weren’t live – but they were also spatial initially. I saw a particular kind of space in listening to Beethoven, and then after sketching that in I saw the space become populated. Color came later.

This whole series was quite important to me, as it was the first real engagement with painting a body of work after the Two Boys. And it was also an extraordinary way to put my relatively new way of working to a kind of test – it really felt that way. I thought – this is a perfect way to work from imagination, to persevere with this strange newish language but in a context, with a structure. It would show me if I was on any kind of path with it or if it held any larger meaning for me – and I found that it really did unleash my imagination.

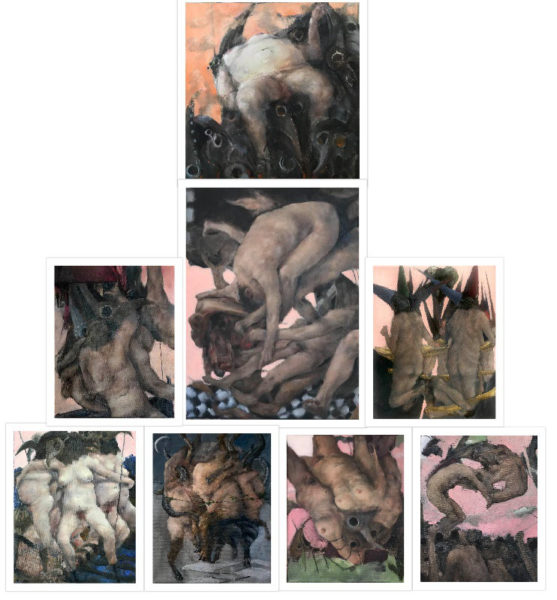

LG: What inspired you to paint your series, wages of pestilence and folly?

Karen Kaapcke: Nothing really inspired me to paint the series initially. I had been home, working in my bedroom because my studio space became unavailable due to Covid-19. I had one child doing her senior year of high school at home, and another kid trying to finish his first year of college at home after his school closed. As a parent, I’m a big believer in doing rather than saying, and so I felt that the most help I could give them through this difficult time was showing them what it looks like to keep getting the work done. I also realized that since working in my studio they had never really seen what it is I do. Well, they’ve seen my work in France and drawing around the house and so on but they’d never really seen that paintings come from regular, hard, daily work. What happened was, I got sick – with Covid–19, and the first day I sat down to work I was already feverish and felt the illness coming on, though I wasn’t able to get tested for it for a couple of days.

As I started painting, the images that began to come to me were historically resonant – my mind was full of images of the plague and the plague masks, and later of dunce caps from Goya, and of the present time. I was kind of working in a fever dream – all these images mixing together, of today’s politicians speaking in what sounded like utter folly as I lay most of the time when I was not working, in bed – feverish and exhausted as debate raged about the very reality of this disease. The folly of the political landscape was even more unreal seen through the lens of my fever. I painted every morning until I couldn’t anymore for the day, with the motivation that that then became a completely thoughtless routine. But I was in my own kind of folly perhaps.

I look at the paintings now and I don’t really even know where they came from. One of the last ones I did I titled Wages of Pestilence and Folly and realized then that that was also the title to the whole series. What is this price we’re paying for this illness and foolishness? And how this is not much different from all the other times when such pestilence had been visited upon us.

The imagery of dunce caps from the middle ages, which has an ambivalent meaning, referring to both the “idiot” and, historically, high intelligence; the imagery of the intersex individual, having aspects of both male and female gender, recurred over and over. I think what I actually have as my subject matter in these paintings is a kind of ambivalent state that is confrontational, disruptive. The fact of this illness, having this illness – and yet swimming in this sea of politicized information and absolute craziness; the two polarities of the basic undeniable reality and fact of the illness alongside the layer of unreality and untruth – of “alternative reality” or facts being spun in the social/political realm. We were and still are literally inhabiting a world of ambivalence, of paradox – and it was so primally disturbing while ill and feverish. This is what I painted in this series. I didn’t plan any painting, and I didn’t know what imagery would come with each piece; they kept on coming and as they are small (most of them are 8×10”) I was finishing each of them in a few days. And part of what I tried to do also is paint the paradox of often disturbing imagery in such a way that you felt compelled to look, to keep looking. And then I got better, and the series ended.

LG: I read that during Occupy Wall Street you spent a lot of time with the protesters at Zuccotti Park and was painting there. Can you talk a little about what painting during this demonstration meant for you? What was the reaction from others? What are your thoughts about painting as a form of protest?

Karen Kaapcke: It was less planned out than you might think. I had been feeling kind of trapped in my studio – both in my work and in the space. Like I was repeating myself within those walls, not thinking beyond a certain idea of working with a model. I needed more or something to shake things up, and I had no idea what that was. So I just one day decided to sublet the studio – to force myself out of the space and out of my comfort zone. I know I have a very determined side, and I told myself that even if I end up painting in the stairwell of my apartment building, I’ll still be able to work. And it will change somehow – it would have to.

Meanwhile, Occupy Wall Street was starting to brew, and I was hearing barely anything about it in the news. I was becoming troubled by this lack of coverage, and also was feeling a strong sympathy to the cause. But as always – it had been a very common and recurring sentiment – I was wrestling with my seeming apolitical position as a painter, and feeling a bit of a crisis (as also happens regularly). It is a very difficult thing to resolve, the fact of having the privilege of painting – however hard-won that privilege may be – in the face of the hardships and tragedies of the world. And I don’t know of any painters who don’t go through this. One morning (pretty much right after subletting my studio) I woke up and realized I needed to go down there, and paint. As soon as I thought this I got anxious, the idea of painting in public, not knowing what I would paint, and so on. But given my context, I felt that was precisely what I needed to feel. Partly, I thought that it’s the least I could do, feel this anxiety and pressure but to be there in that way, and partly I realized that I was answering to my anger at how little the media was covering this. I was a way of recognizing what they were doing and communicating it.

In terms of the attention from others, I was largely ignored which was terrific. A few times someone came and sat with me, and when they tried to chat I just said I wasn’t up for talking, just painting and every single person understood that. I did get filmed for the news one time and just tried not to let it bother me. But I did begin to see something about painting. Not that painting could be a form of protest but as a way of documenting, and of bearing witness. I really felt that the very act of being there painting them, and in such a simple way (I did these rather simple ‘plein air’ sketches of just what I saw, with no commentary or anything betraying any beliefs), was itself important. I didn’t really care what the paintings themselves looked like – that seemed secondary to the act of painting them. So one of the lessons I learned was that painting is by its nature political if it is responding to the human condition, just life itself. Not turning away from anything – and that this matters more than the particular content, or ‘message’ of a painting.

I feel it is important to add though that this way that painting has of bearing witness or documenting something, or of giving form to something that hadn’t been made visible before gets its power from being non-verbal. When I see attempts to make what maybe you’re thinking of when you say ‘protest art’, this work is usually either very verbal or over-determined in its meaning, telling you how to think about something. Not only does this become more like propaganda for that reason, but it loses efficacy. But it’s also not really true; the human condition is very paradoxical and full of unresolved questions. Anything that shows me too much of the answers just feels less true. There was a moment after these OWS paintings when I finally realized through my work what a ‘visual metaphor’ is – this for me is how a painting can approach “political painting”. But in a way that I hope communicates if anything the difficulty of reducing meanings, the complexity of human life, the questions, and not the answers. I really dislike the terms “political painting” and “protest art” – but not because painting shouldn’t be that – but because they lend themselves to oversimplification and didacticism and to a verbal pushing of meaning. Non-verbal meaning is I feel by its nature ambiguous and much more potentially powerful.

LG: When I was in art school I had teachers who pushed painting representationally in a traditional manner and discouraged experimentation as that would often lead to dead ends and cliche. Other teachers worried that perfecting skills would lead to the stifling of expression, creativity, and individuality.

The art critic Jerry Saltz famously said, “All great contemporary artists, schooled or not, are essentially self-taught and are de-skilling like crazy. I don’t look for skill in art… skill has nothing to do with technical proficiency… I’m interested in people who rethink skill, who redefine or reimagine it: an engineer, say, who builds rockets from rocks.”

What can you say that adds to this controversy?

Karen Kaapcke: I think the term “de-skill” is like the term “defund” in “Defund the police”. It’s catchy but usually leads to a kind of knee-jerk reaction. When you take the time to look into what is being said a bit, you see that it really doesn’t mean what you maybe initially thought it means. It doesn’t mean to literally and totally “defund” as in take all money away; it means more often than not a redistribution of funds, and a rethinking of what the role of the police is – what are we funding, exactly, when we fund. So maybe it’s a bad choice of words – and so is de-skilling. I don’t really use the term.

I don’t think “de-skilling” really means literally not working with any skill. I do agree with the second half of what Saltz says, that it is more subtly about a reconsideration of what skill means. His statement is a little contradictory, he says both ”I don’t look for skill in art” but then he more interestingly kind of redefines skill: “…skill has nothing to do with technical proficiency…I’m interested in people who rethink skill…who builds rockets from rocks”. So he does look for it, but it’s a different “it”. A much more interesting thought. But the first part is the one that people will react to.

I am someone who was very trained in a certain skill but I do not equate masterful work with this skill. I allocate my funding differently so to speak: rather than seeing it as de-skilling, I see it as using a certain skill sometimes, when it is required by the work, but the work is bigger than any one skill set. There are so many others of course: the skill of composition, the skill of story-telling, the skill of color, the skill of paint application, the skill of song.

So there is also a problem with the term “skill”. I think the real skill of painting is to be able to paint what one intends, and this is really the most difficult thing. Sometimes the word “skill” tricks us into thinking there is a kind of teleology to how art has evolved. I look at and incorporate a lot of medieval ideas of space and color, and this language is used in a completely different way than it was used after the invention of the Renaissance perspective for example. It is not less valuable or valid because of that though and of course, medieval artists were not less skilled. The notion that rendering a nose more and more “perfectly” is better – this is not my idea of what makes better art. A perfectly rendered nose is no better than a Fra Angelico or a Central African Nkisi power figure.

“Deskilling” is like those words that lose meaning the more you look at it. It has to be contextual. You can see what people mean when they use it and what certain artists are up to. A lot of what is called de-skilled art is a strong reaction to the kind of painting where a high level of skill became the definition of good painting to the neglect of almost anything else. So there is a need to break through that, like Art Brut reacting to overly refined art, or artists that encounter works of other cultures and undergo a shift or insight regarding their work, or artists confronting the need to make a certain kind of art after the experience of the Holocaust. I remember a period I went through where I had to make “ugly art” – people were asking me what the hell I was doing, but I really needed to get out of what felt like a trap – that of making pretty pictures, and of trying to please others with my work. That may have been a kind of de-skilling, though I didn’t use that word. The problem I have is when it gets taken up as a rallying cry for its own sake and this is when it not only makes no sense but may be kind of dangerous when as you mentioned in your question, instructors might use it to keep young artists or students away from learning certain skills that might prove helpful or necessary in their later work.

In terms of the way art is taught in art schools, I honestly don’t know how anyone could discourage either experimentation or the perfecting of any skills. I could understand saying that in a particular class you will be focusing only on certain skills, or saying that in a class the work is going to be strictly experimental. I know this kind of thing is very common and I honestly don’t get it – but nobody who is truly creative is going to be deterred from experimenting or from seeking out the skills they want or need. Maybe this is why I intuitively rejected going to any academic art program.

I do have some stories. My main teacher, Ted Jacobs, got really mad at me when I was working with him because I started doing these big abstract paintings on the floor of an abandoned garage in France where we were studying. He told me that I needed to stop, that it was going to damage me and get in the way of what I was learning. And I disagreed so strongly that we didn’t talk for years. And then after we got back in touch, and I was painting with the figure again, he said he also had spent years working abstractly and so on, but that he felt that as a teacher there was this fear or risk that students would fall off the deep end or something. I’m not even really sure – but he then also said that he could now share this with me because I “came back”. A bit later on I had this boyfriend who was an abstract artist, and he was constantly asking me why I bothered with the figure. That relationship didn’t last too long. But this was not uncommon at all.

You see cliche all around no matter the style. I think dead-ends happen on both sides and maybe it actually is a result of not letting yourself bend, maybe the dead-end is the rigidity – not really even so much being closed to other ways of working, but somehow an inability to prioritize the needs of the work. It all takes much longer though to learn, and you are pretty much an old lady by the time any of your work might start to make any sense.

LG: Many painters, both abstract and figurative, that I’ve talked to feel art primarily needs to be about the picture, the formal concerns, and that politics will only weaken the painting. I tend to agree with this analysis overall but also think that the definition of what’s political can be too narrow sometimes.

Many of the greatest painters made masterpieces that had political meanings in their time cloaked in the religious subject matter. Of course, it was less likely to be protest art, instead, propaganda for the church that was elevated to a sublime degree from the beauty and power of the art itself. Paintings like the Sistine Chapel depicted biblical stories that were used by the church to reinforce the religious beliefs central to their dogma and hold on to political power. If you can accept that premise, why couldn’t art today similarly embrace politics, without sacrificing the pictorial structure and beauty?

Karen Kaapcke: Well, I think it can – but I think that there is a third thing that needs to be mentioned. What has become important to me in painting is this idea of a ‘visual metaphor’, or visual idea (I know I have mentioned this several times), which is a kind of content that is inseparable from more formal aspects of the painting. It is where they meet in a sense – but I almost feel as though this way of thinking got ecIipsed in the resurgence of realism, where so much emphasis was (maybe necessary for a time) placed upon learning a particular technique that many felt was in danger of getting lost. Painting that is so focused on the observed world can run the risk of being very literal – and of course, some of the greatest painters are committed to this literalness – Lucien Freud for example. Literalness is one of the points. But when talking about “political art” this kind of literalness is its undoing. I agree that it does weaken the work.

There is a way of responding to the world however where the things of the world carry a larger or richer potential for meaning. I spent a lot of time not long ago looking at a medieval painting in order to expose myself to a language of color (I was particularly interested in what I saw as a language of red). It seemed to me that red, for example, was being used for so many reasons – not only to move the eye around the work, thereby figuring narratively but also in ways that were beyond my reason but were there in the painting and impacted the looking. I wasn’t hoping to unlock the meaning of this red – but it just seemed important to me that red was used with meaning, and not just to portray something that may have been red. Around this time I was doing my Raft paintings, where red began to take on importance.

Similarly with medieval space – I had the strong sense that the use of various spatial constructions and proportions was quite meaningful in the work and that it was clearly not just a representation of how an artist saw the world. Much of this has been studied – but again, I didn’t want to know how or what these meanings were in the paintings – I wanted exposure more to the sense of space containing meaning beyond realism. All of this is sort of what I mean by the things of the world functioning as visual metaphors, pointing at once to what they are, and beyond themselves. So in this way work can carry a very real and strong political meaning but also so much more and that is what makes them successful both as beautiful paintings but also as pretty charged up with political meaning – in Delacroix’s painting “Liberty Leading the People”, the raft of people in the sea is resonant of so much more – this whole sense in the painting of being cast in the wild, so near a horrible unjust death, yet being led to safety. The meaning is not over-determined, he is not telling us about the French Revolution specifically – he is speaking of the human condition and we all feel this. I don’t know how, for any figurative painter, this whole side of being human could be unimportant even if it’s not to your taste to paint that way.

In one of my paintings, Grief I (Mourning), which I painted in response to an old friend’s suicide, I painted a bare mattress with figures on it. I didn’t know right away why it had to be bare, but I knew it had to be – and afterwards I can see how the raw, cold quality is what grief can feel like. But maybe the mattress means something else to another viewer. A life-raft? And in later painting, the mattress did become a raft of sorts. It grew as a metaphor. And then (in the Grief painting) a strange shape of white paint curving off to the right – I felt the formal need for this, and so put it in, but as I saw right away that it seemed to be the lifting of a spirit – whether of the departed or of the mourner, no matter – I left it in. A formal/abstract element that carried the meaning of the imagery.

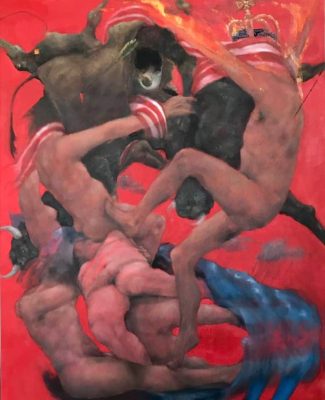

A very recent series of paintings have more of what you could call political references. The first in the group, Called Combustion (The Mad King) has elements of an American flag wending through it. But I took pains to keep it at least somewhat disguised. I did want a reference to it though, and the balance of how much of it to show was crucial. What guided a lot of the decision of how much to show were very formal concerns – the formal and the content were merging in how the flag had to wrap through the bodies. And the king – who is this king? The animals in the group of figures, are the bodies fighting them? Or taming them? Who is winning this fight? These were all questions I was asking myself while playing with the formal aspects of the movement of the bodies and the placement of the dark masses. And then, when I saw that the king figure had to burst into flames – again, it was a formal decision that was wedded to meaning – I was wondering about all the red in the painting, all the heat, and the reasonable side of me was advising to balance that out with some more cools, that there was too much red, too much heat – but then I saw that no, that was the point – the heat – and I had to actually push it further. When I started playing with the idea of his arm turning into fire I saw some flames emerge as well from his body – he was self-combusting. This became such a rich visual metaphor for me and finished off the painting. But I do not know exactly what it means. In fact, it doesn’t ‘exactly’ mean anything.

There is a very important balance of content and formal concerns in a work, and what I think is that for me there needs to be such a tight balance in a successful work that it is experienced as a kind of tension. One problem I often have with not only much ‘political’ work but a lot of representational work in general, is that there is a tendency that I see to make it all about the image. All about the content, in a way that over determines its meaning, which answers instead of asking, As if it’s telling us what to think instead of leaving us wondering, leaving us more open and curious.

i thought the t the concept of patience was important for students or persons in any field.as they come to embrace themselves and their work.

Hi Karen,

I am your old friend from France 1998. I think of you quite often and your importance in opening my mind to the classical and technical knowledge I was seeking

since childhood. God bless Ted and what he transmitted to young people and the world. I lived a beautiful life in art, as a teacher, artist, corporate designer and quite frankly more than dabbling in all of the arts. I looked at your profile, the U-Tube of you speaking to your students and as i admired you and your talents years ago,

I certainly do now. Next year i will be eighty. I continued to paint and draw, discovering after I retired from teaching on 2016(age 70), only one local college actually taught life drawing. The teachers that began to come into my school system were vastly different then my school teachers growing who were actually accomplished artists. Enclosed I have included a couple of paintings. Thank you again for our friendship at that time so long ago.

warmest wishes(glad to see your arthritis did not hold you back.

Cheryl Kleiner