I’m delighted to share this interview, conducted by email, with the San Francisco-based painter John McNamara. There is much to see and think about his enigmatic subject matter, compositional inventions, and painterly surfaces. I am very pleased that he was willing to share such a detailed and nuanced background of his long and accomplished career as a painter. In looking at his works I’m continually surprised and challenged by his contrarian impulses to modernist dictums about what’s proper or permissible in painting. His work seems to invite us to join him in a hopelessly complex board game, where you make up the rules as you go along in something like an alchemic version of the Snakes and Ladders game where form wrestles with content and the picture’s destiny is advanced by chance rolls of memory, curiosity, and desire.

In a 2018 interview on the Studio Work blog, McNamara stated:

I don’t however want to be didactic in any way. I’d much rather feel things out, rather than self-consciously and analytically think the meaning out. I think more interesting meaning comes forth from/through intuition. And frankly, there are always many possible reads to any piece of work. My hope is to provoke a sense of curiosity within the viewer, similar to the curiosity I feel when making a painting. I strive to make a painting that has visual and conceptual engagement.

From a statement from the 2013 exhibition at The Painting Center in NYC:

John McNamara has investigated the relationship between painting and photography for the past twenty-eight years, through making paintings that engage photography as a hidden painted element. Since the photography literally exists beneath the surface, there is a strange conceptual ambiguity relational to the frozen moment of a person, place, or thing that lies underneath the interpretive nature of the painting process on top. In a number of his paintings McNamara uses photographs of people who are engaged doing things in different parts of the world on a particular day of a year, to make a new sense of place and time. In other pieces, he may take people of roughly the same age, but coming from different decades, and fuse them into the painted reality. McNamara is sensitive to the “time machine” aspect of collage and its potential. The content of his work investigates conceptions of transcendence, moments in popular culture, and sharable life realities. McNamara considers his paintings to be open investigative narratives. His goal in making paintings is to provoke a sense of curiosity about meaning within the viewer, similar to the surprise and curiosity he experiences when constructing a painting.

Larry Groff: Please tell us how you got your start with artmaking. I understand that in part, it started as a way to avoid the draft during the Vietnam War era. I’m also curious to know about your early mentor – who was also a professional boxer?

John McNamara: I grew up in a working-class family in Alston, Mass. When I was quite young, my father bought me a “paint by numbers” kit. My father had aspirations of becoming an artist, but after the 1929 Stock Market crash, both he and my mother had to work to support their families. I made a good deal of paint by number pictures, finishing with the “Last Supper!” When I was 12 or so, I started to make paintings from photos I liked. I didn’t have all of the colors I needed but made due. I was an underwhelming student at St Columbkille School in Brighton for 12 years. I really hadn’t thought of becoming an artist for my life’s work, but when I was 16, my mother invited her friend over to look at my work. His name was Joe Santoro. He was an ex-marine, former prizefighter, who now ran the Watertown School system. He was also a watercolor artist, who made watercolors with a Winslow Homer sense to them.

He looked at all of my work, gave me some pointers, and then mentioned that I should take Saturday Art classes at Mass Art during the fall of 1966 when I was a senior in High School. I did that and kept talking with Joe. I applied only to Massachusetts College of Art and wasn’t sure what would happen. During the winter of 1967, I received a letter telling me I was accepted. I couldn’t believe it! I was told earlier by the academic dean at Mass Art, that my grades were too low for me to be admitted. I found out some years later, that Joe S and the dean, Henry Steeger, had been in the Marines together. I think Joe asked the dean to give me a pass on the academics since my art-making potential was strong. Steeger went along with Joe, and I was admitted.

I really hadn’t thought much about the Vietnam War during high school. I’d see the death and destruction on the nightly news, so I was aware of what was happening. It seemed unreal to me, but I would have gone if I hadn’t gotten into Mass Art, and wouldn’t have tried to avoid it. When I got to Mass Art, and a few of the students were returning from the war, that’s when I knew I wouldn’t go, based on what they told me and others in detail, about what was going on there. My initially wanting to go to Mass. Art was based solely on my wanting to pursue art-making as my life/career.

The government had a lottery system in place as I got nearer to graduating Mass Art. They made an offer, that if you gave up your student deferment, and your number wasn’t called during the last few months of 1970, you would become 1A second priority, meaning the war dept. would have to go 1 through 365, and then come back to do the process again, before your number would be called. Since I was around number 256, I decided to give the offer a try. And it worked out.

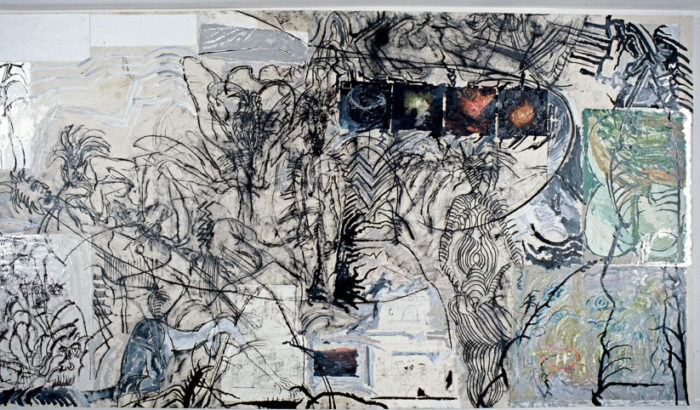

The Nature of Inquisitive Persistence, 9 ft. 3 1/4 × 8 ft. 7 1/4 in., Oil on canvas,1984–85, Edith C. Blum Fund, Metropolitan Museum of Art

LG: What was your education like during your undergraduate and graduate years at Mass Art? How well did it prepare you to become a painter?

John McNamara: Attending Mass. Art at 17, in 1967, was a tremendous opportunity for me. I loved every bit of it. I was among people who had similar goals, and I worked like a demon right up through graduation. Three instructors had the greatest influence on my coming of age as a painter. They were Jeremy Foss, Rob Moore, and Dan Kelleher. I saw making paintings as my calling, based on the influence of these teachers. They were examples of artists who taught, their painting was a vocation, and teaching an avocation. The spring semester before I graduated, I had already begun working on a group of paintings to be shown in the fall of 1971. So there was no letdown after graduation from Mass. Art for me.

LG: Can you say something about your early experiences after leaving school? I understand your paintings were well-received early on, getting into a number of group shows in museums such as the Rose Art Museum and the ICA in Boston. How did success affect your growth as an artist?

John McNamara: I was 21 when I graduated from Mass. Art. For the next seven years, I painted, away from any notion of recognition. It wasn’t until Roger Kizik, who worked at the Rose Art Museum, mentioned me to Carl Belz, saying he should take a look at my work. He did and included me in a show at the Rose in 1978. That began career things more in earnest. Previous to that show, in the fall of 1977, I installed a painting in the restaurant of the old ICA on Boylston St., which kind of got some people to see my work. In January of 1980, I had my first show at Cutler/Stavaridis Gallery on Congress St. in Boston. Things really began to pick up after that show. Ken Baker reviewed me in the Boston Phoenix, and Elizabeth Findley reviewed me in Art in America. I kept shifting the process of my work while continuing to explore a kind of transcendent space in the paintings. I think that early on, success had an effect on me, in that I wanted to push the scale and complexity of the pieces for the “next show.” It was exciting for sure. But anyone who has looked at my output over the decades can see, I had no hesitation to engage different approaches and subjects. I think in the end, this was confusing to some people.

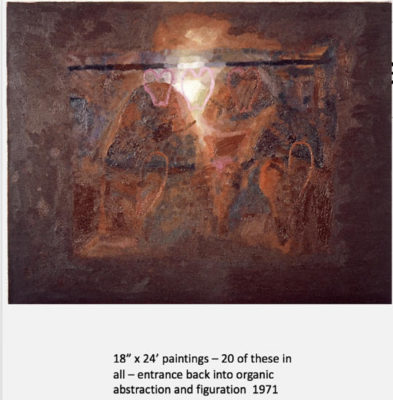

LG: How did your work evolve from abstraction to being more figurative and narrative? Was there anything, in particular, that was a catalyst in making this change?

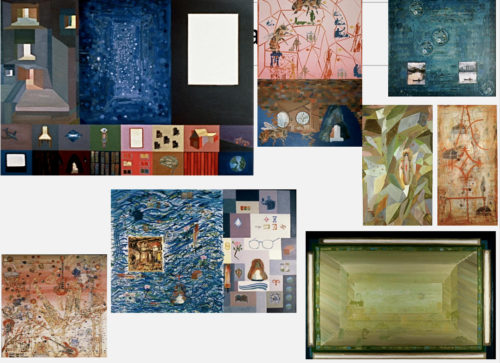

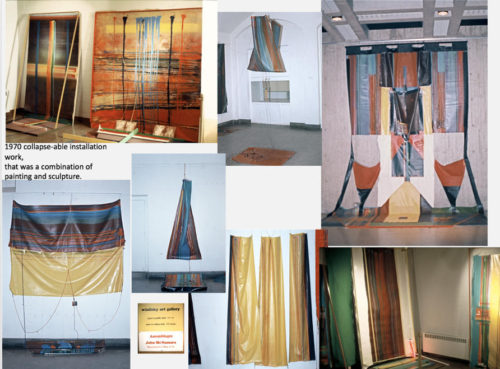

John McNamara: While I was at Mass Art, I went back and forth between non-objective, abstract, and figural subjects. I was very interested in the contemporary art movements present at that time. Amalgams that fluctuated between painting and sculpture and installation.

The above would be examples of that. I was also interested in 19th French painting. Making space within painting also continually fascinated me. Often figural compositions employed spatial qualities. The paintings of Morris Louis were very important to me. Eva Hesse also fascinated me. Henri Rousseau’s figural compositions influenced me, relational to the figure in a magical landscape. The painting below is an example. It was made with minimal prep and worked up in an intuitive way. I let the narrative as such, pour out of me. I relied heavily on intuition, right brain trust.

My small painting above was directly influenced by Rembrandt’s Conspiracy.

Although one might say I was painting my way through history, this shifting back and forth from contemporary abstraction to the figure worked for me, so much so, that it has occurred right up until the present moment. Since 1993, I have fused aspects of abstraction with figural situations.

LG: In looking at your paintings I’ll occasionally see traces of other artists like the works of Jess, Paul Klee, Robert Rauschenberg, Edward Kienholz, cubist painters, and many more. Can you say something about the artists that been most influential to you and why? Picasso has been famously quoted with his declaration “good artists borrow, great artists steal.” You made a similar statement in your gallery talk. Why is stealing not a crime in art-making?

John McNamara: I’m going to have to break this answer down, starting with the abstract expressionists. I saw my first Pollock when I was 17. I instantly got what he was saying, and how important intuition was in art. He made me aware of invention, working one’s way through an art-making process. I’m thinking primarily about his drip paintings. There was an elegance and sureness of flow that these paintings had.

Morris Louis and George Seurat were strong influences on me also. The key element that each shared was their ability to engage a process to its end, in a very clean, effortless way. They had a methodology, which was very clear. Each stayed the course until the work was completed, in Seurat’s case, 1.6 million points of paint in A Sunday on La Grande Jatte. Seurat’s use of painting his frames the same way he painted the canvas has had a continuing effect on my own use of a frame in a frame in a number of my paintings. To me, these artists were alla prima painters of sorts. There was a freshness to their process. Put it down and leave it down. In contrast, artists like DeKooning and Guston were always breaking things down, at war with their paintings, finally arriving at resolution. I more and more wanted a process that was immediate and fresh. No matter how many layers I put on a painting, I’m always seeing it as an addition, not something to cover up a mistake.

The painters you see traces of were definitely people I had looked at carefully. When I was very young, say 20, I’d appropriate various artists’ conceptual and constructive components, without any hesitation. I felt I was using these elements in my own way to make a new whole. I’m always appropriating.

LG: How do you go about selecting and using the photos for your paintings?

John McNamara: My paintings during the 1980’s, utilized painted photography in certain areas. I liked painting over the photo, many are taken from calendar images.

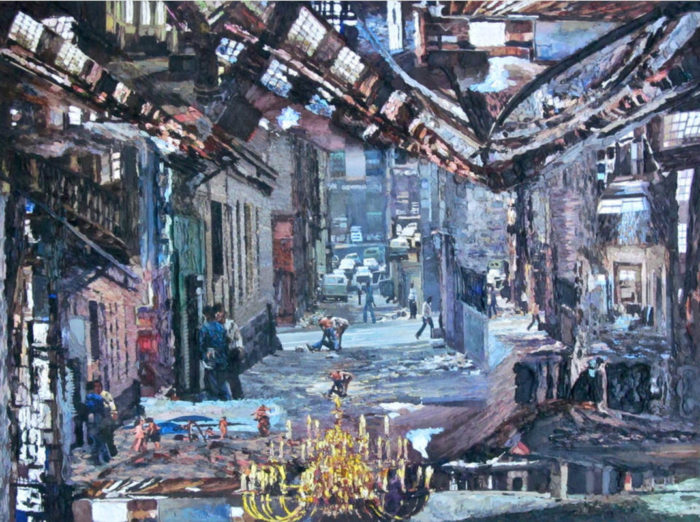

But in the spring of 1993, I began working on wooden panels, where I’d use various images that could tell a story. Below was one of the first pieces done in this manner. I made a kind of puzzle with the images, one where all pieces are cut to fit together like a puzzle. I still use this process today. Then I would paint.

A number of the early paintings were a deconstruction of art historical tropes. I went then, and do now, to search for images that would be part of the human narrative, of small and big issues, that people generally encounter. Over the years, I have built up an image bank. Often a new image will catch my interest, and I will go to the bank to try other images with it. I end up playing with the image/s and see what they conspire to do.

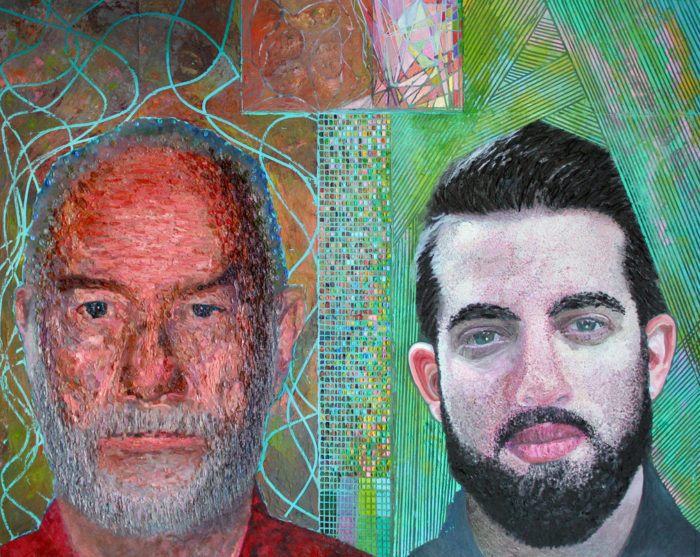

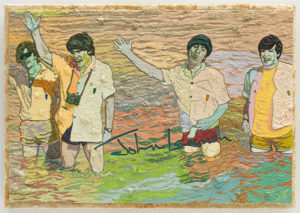

One of my recent paintings came to meaning in this way. Its title is “Painters of the Past”

The figures in this painting were taken from a photograph by Aaron Chang, sometime in the mid 1980’s. It appears that Chang came upon the young men in his travels, in the evening, near Highway 17, Charleston, South Carolina.

Eventually, a wide range of images by various photographers was used to make a book. This book covered a number of topics in the various U. S. States. Unfortunately, I don’t have the book anymore. The heading for Chang’s photograph read:

“In Charleston, Coming to Terms With the Past: The compulsion to engage the Charleston area’s history as a slave-trading center was, for the writer, a visceral thing, akin to the urge to revisit a crime scene.”

I’ve had the young men’s image for some time. What drew me to the image initially, was the way in which this group of guys appeared to be relating to each other. I felt they had worked together for a while and had a connection to one another, a comfortableness, a friendship. Of course, photographs are fiction in one way or another, and realizing that I couldn’t really know them. I ended up putting them in an architectural construction that warped time and physical structure, while also having a painting of them on the wall. My artist statement below has guided me over the last twenty-seven years.

“I investigate the relationship between painting and photography, making paintings that engage photography as an overt, painted element. Since the photography literally exists beneath the painting’s surface, I find a strange conceptual ambiguity, relational to the frozen moment of a person, place, or thing that lie underneath the interpretive nature of the painting process. I am sensitive to the possibilities of the “time machine” aspect of collage, also playing with this element to engage meaning.

The content of my work focuses on conceptions of transcendence, moments in popular culture, and sharable life realities. I consider my paintings to be open, investigative narratives. My hope is to provoke a sense of curiosity within the viewer, similar to the curiosity I feel when making a painting. I strive to make a painting that has visual and conceptual engagement.”

LG: Do you manipulate the photos digitally and then print them or just take them as you find them? Anything special about how you glue them to the canvas or board?

John McNamara: Other than enhancing color, I don’t manipulate the photos digitally. I send my photos to a printing store, having 13” x 17” hard copies made. I use a 100pd paper for the copies. This gives the puzzle-making application more robust. I use Yes glue directly from the container to stick puzzle pieces without wrinkling. I use a printmaking brayer to roll out the puzzle sections.

LG: Do you prepare the photos in any special way to better protect them or the oil paint’s adhesion? Like applying resin before painting?

John McNamara: I take the freshly glued piece on the panel outside, and spray eight, light coats of matt Krylon sealant on the surface. Once dry, this makes a stable surface on which to paint.

LG: What are some of your most important considerations with color in your paintings?

John McNamara: I work out color ideas while putting the collage together. The process is very physical, with cuts happening right on the wooden panel. I feel the main reason why my color doesn’t repeat is directly related to this process. I have used Color-aid paper, and bits and pieces from magazines for developing color ideas. Once the painting begins, I make many changes with the color, while staying within the overall color idea for the painting.

LG: Many of your works have richly impasto surfaces and geometric configurations of thick paint that seems to float above the rest of the painting. Can you say something about that?

John McNamara: I have always been interested in the physical nature, and presence of paint. When I was in art school, we had a class where we learned how to make both oil and acrylic paint. Oil paint has the pigment, and I would put plenty of the pigment in the blender, followed by the linseed oil, a dispersal agent, and an anti-fungus chemical. Then blend. The paint we were making was equal to the best paint one could buy. For acrylic, the binder I used was called AC-34, a liquid vinyl sold by WR Grace company. I used these paints on my early installation pieces.

I came to believe that the artist’s fingerprint was in the material paint. That is why the paint presence is so strong in my paintings. I use a number of visual devices to up the ante when I’m making a painting. There are quite a bit of taped areas in my paintings. I respond to the hard edge as it relates to the more organic applications of the paint. I sometimes hand cut the tape to 1/16 of an inch, so thin, that you really have to examine the painting closely to find the geometry.

Getting up close to a painting of mine should give a sense of surprise in what is discovered. I believe the excitement I feel while making the painting, will possibly be a moment of unanticipated joy/surprise for the viewer.

LG: In a gallery talk (link to talk here), you mentioned that you don’t often plan out a painting beforehand and that a painting direction often takes on a life of its own. Can you say something about your process with regard to how you compose and make your paintings?

John McNamara: A backdrop: In the spring of 1989, after my final show at Stavaridis Gallery, I began to question my painting process and my paintings. I had gotten so good at what I was doing, I was in a disconnection about valuing, or finding meaning in my paintings. I stopped painting for almost four months, considering at that time as to whether I wanted to become an object maker. I realized that would be running away from painting, so I felt I needed to find a way to make painting have meaning again.

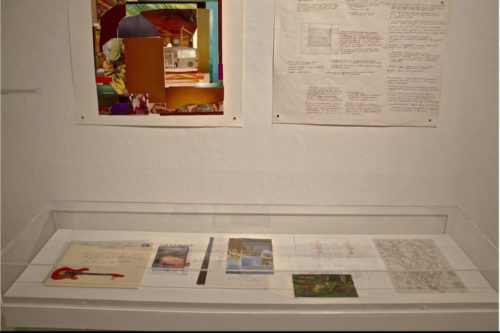

The answer was to make my paintings about ideas and human experiences. Each painting’s point of departure would be revealed in the title. It was going to be necessary, however, to make a plan for each painting. I used color aid and other color sources, and I wrote my thoughts about what the piece was going to present. Below is an example of what that looked like.

The above paintings, made between 1989 and 1992, are examples of work without employing collage that I was making during that time.

But in the spring of 1993, while I was teaching at SFAI, I began to use painted collage expressly. I reached a point where preplanning got a bit out of hand and became constraining. If I used painted collage, my research materials were directly taken from sourced visuals. Playing with the pieces of paper, allowed my right brain to pick up more of the unexpected, but totally relational insights.

The process has remained the same, while the positive anticipation toward the next idea/painting remains consistent.

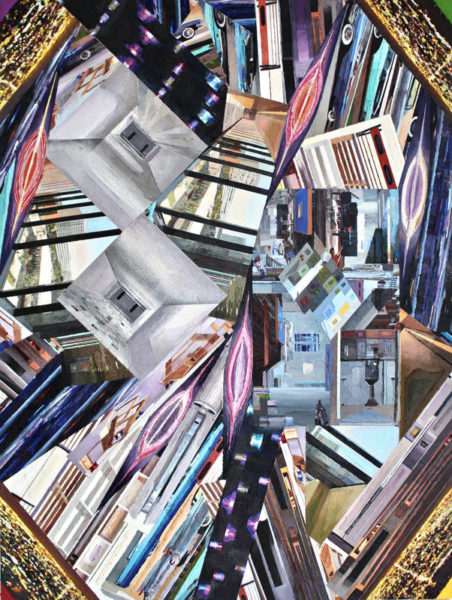

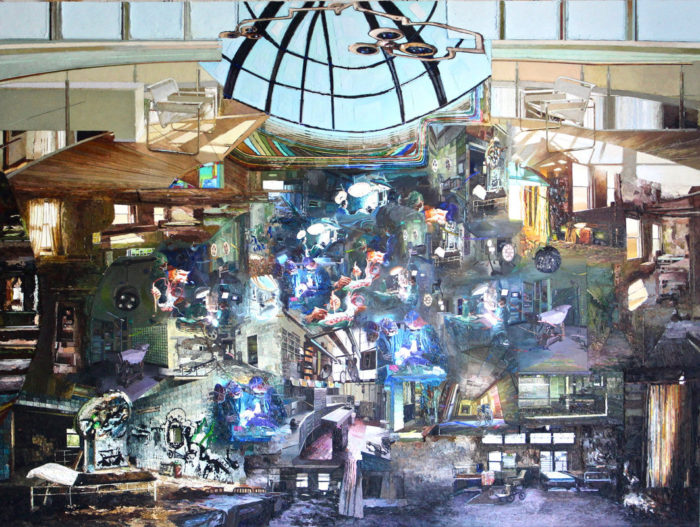

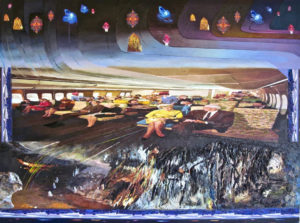

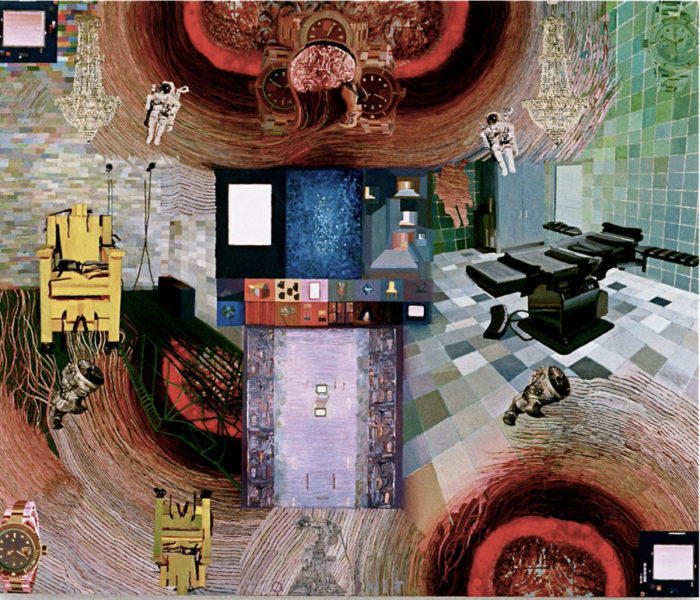

LG: I’m curious if there might be a connection to dreams or even maybe some type of Jungian dream analysis aspect to the subject matter in your work? For instance, some of your paintings show multiple perspectives of rooms on different levels of a building or home – like in your Whittling Down and Painters of the Past?

John McNamara: The catalyst for the Whittling Down piece was based on a conversation I had with a friend some years back. She had cancer and was receiving rounds of chemo at various points over a two-year period. I commented on how great she looked, and asked her how she was doing. She told me how the chemo was weighing her down. Then she made a reference that chemo’s effect was like a pencil that was constantly getting sharpened. Eventually, there was no more pencil/person left.

I chose a series of images of cancer operations from the early, mid, and late 20th century, as well as one where a robot is the surgeon’s hand. I also included images of abandoned operating theaters and hospital rooms. I, like most people, find these abandoned spaces scarily seductive. The top images were taken from a book on lofts. Berlin 230M2, architect: Alfred Peuker – Berlin430M2: Höing Architekts.

As with all my paintings, I develop a point of departure and then see where the process leads me, a process very familiar to most painters.

The room definitely has subconscious meaning for me, a place of retreat/safety, and restraint. Architecture in general finds its way into many of my paintings. The Jungian dream analysis is most probably there. I can’t say no to that. I’m very intuitive. I trust feeling to get me there. The logic comes in in the collecting of materials for a given piece, and the initial layout. The best place to be is where one has good trust in the right and left sides of the brain, with the corpus callosum doing a good mediating job.

When I was nine yrs. old, I got very sick. My parents kept thinking I would get better. They kept me in bed for three weeks, as I got sicker and sicker, chills, temperature, etc. Finally, my mother took me to the hospital, where I was diagnosed with advanced pneumonia. I was in an oxygen tent for two weeks, and another two weeks until I could go home. Penicillin shots twice a day. I actually felt fine as a nine-year-old being in the hospital. I knew they would take care of me, whereas my parents were dysfunctional and messed up. To this day, I feel comfortable in hospitals.

Cancer had been a continually occurring fear of my mother’s. Her mom and father had died from it, and she would always talk about it to me as a young kid. My friend who made that statement about her journey with cancer caught my attention. Entropy and aging show themselves in this painting. I try not to be didactic with my work. As far as I’m concerned, it is open for various readings, and because my subconscious/right brain is so much afoot, there are always meanings others perceive, that when told to me, I can see.

LG: If painting decisions made during moments of heightened concentration can tap into one’s unconscious in ways that the more left-brained activity can be blocked from.

I’m curious if you might respond to this quote by Jung below in relation to your paintings.

Jung said: “I have noticed that dreams are as simple or as complicated as the dreamer is himself, only they are always a little bit ahead of the dreamer’s consciousness. I do not understand my own dreams any better than any of you, for they are always somewhat beyond my grasp and I have the same trouble with them as anyone who knows nothing about dream interpretation. Knowledge is no advantage when it is a matter of one’s own dreams.”

John McNamara: I agree with what Jung is saying here. The one thing that I don’t know, is if dreams portend the future. I feel that my subconscious/right brain functions lead me to the best choices within the making of my work.

LG: There is an epic quality of huge deep spaces, multiple vantage points, and multiple possible storylines to many of your large paintings. Grand history paintings such as The Battle of Issus’ by Albrecht Altdorfer come to mind for me. What attracts you to working on large scale paintings?

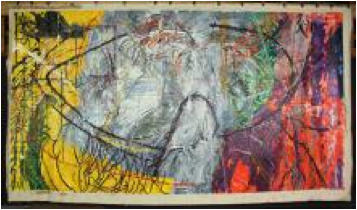

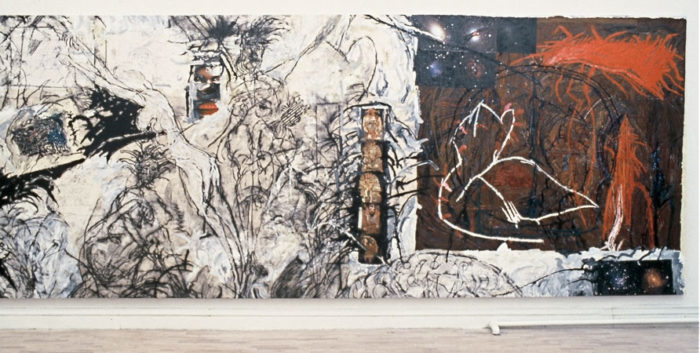

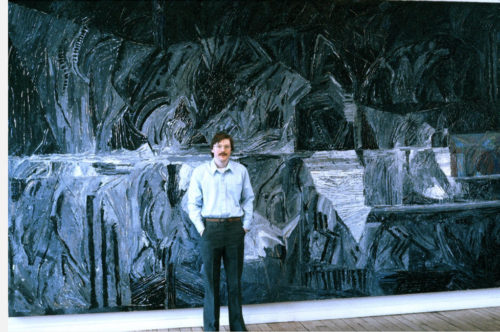

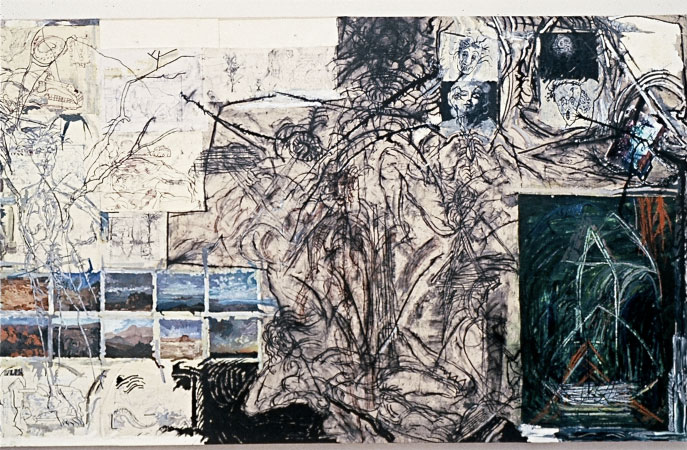

John McNamara: When I was in my 20’s and 30’s, I constantly made big paintings. The painting below was 9’ x 17’. I made a number of paintings at this size. Very few survived, a few of them being in institutions. The painting above is in the Honolulu Museum of Art. I was a bit taken with the of the heroic for sure, but I also was interested in the idea of intimacy on a large scale. An environment of intimacy. Starting in 1984, I became overtaken by Neo-Ex, and in 84, 85, let the paint really fly! It was on some level a false lead, but one I had to explore, to get out of my system. Albrecht Altdorfer’s paintings are amazing! And ironically, very intimate.

In the last 27 yrs. the largest painting I’ve made is 48 x 72 inches. That was last year. When I was making those large paintings, something 4’ x 6’ seemed like a study. My thinking about scale got very distorted. My thinking back in those days aligned with a heroic stance on what paintings had to be.

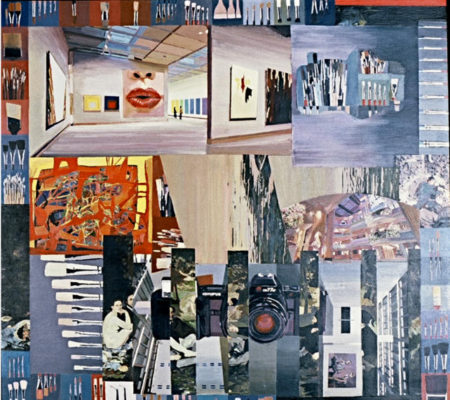

LG: You recently had a retrospective exhibition titled A Visual Dictionary What did this title mean for you in relation to your show?

John McNamara: This show was conceived in its entirety by Farley Gwazda, the director of the Worth Ryder Gallery at Cal. I asked him if he would put the show together. He came up with the title, which was based in part on a series of generic images from a visual dictionary. I had taken these images and tried to give them a new life as paintings. Below is an example of two of the paintings, 16 x 20 inches and 12 x 20 inches.

I turned the show over to Farley because I truly respected him, and because I had always made the choices in shows previous, and wanted to allow another to make the choices.

LG: What does it mean to say a visual thing is poetic?

John McNamara: Usually, paintings that are poetic are valued more from a feeling they give, rather than from a descriptive characterization. I never considered myself a poetic painter. Well, maybe that’s not entirely true. The painting below was made in 1987/88. It’s influenced by Thomas Cole’s,Expulsion from the Garden.

There may be others along the way that could be seen as poetic, but it’s always problematic to self-identify as poetic. It’s like saying: I make beautiful paintings. This leads one to deduce that it’s possible to consciously make a poetic or beautiful painting, when in fact, beauty or poetics come directly from the artist’s process, not being connected to self-consciousness.

LG: What more can you say about the collage aspect to many of your paintings and the paste-ups of photographs that you paint on top of?

John McNamara: All of my work starting in the spring of 1993 is painted collage, where the vast majority have paint completely covering the photographic element.

The first part of my artist statement focuses on this process.

“I investigate the relationship between painting and photography, making paintings that engage photography as an overt, painted element. Since the photography literally exists beneath the painting’s surface, I find a strange conceptual ambiguity, relational to the frozen moment of a person, place, or thing that lie underneath the interpretive nature of the painting process. I am sensitive to the possibilities of the “time machine” aspect of collage, also playing with this element to engage meaning.”

DeWitt Cheng wrote a catalog essay for a show of mine, and in part said:

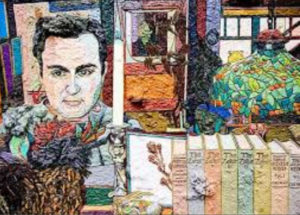

Cubist and Dadaist collage, developing with Johns’ and Rauschenberg’s hybrid 2D/3D artworks and Pop Art’s mass media image appropriations. McNamara continues this rich tradition by assembling printed images from magazines and other sources. Instead of presenting the works as is, however, or re-photographing them (or composing them in the computer), McNamara repaints the images in oils, preserving the source material in idealized, unchanging form, atop the original material. His unorthodox practice is analogous to, say, decorating mummy cases with encaustic portraits of upwardly mobile dead Egyptians, or making a 1:1 scale map of the topography underfoot, as in Borges’ story quoted above. McNamara, fascinated with combining photographic frozen moments from different eras and areas, and preserving them in the amber of art, writes: “For me, collage is a time machine of sorts. The painted skin on top jettisons the photo document into the world of painting; but these people, places and things still speak from underneath the painted skin.” The artist thus practices a kind of Photorealist painting—he particularly admires the complex urban landscapes of Richard Estes— crossed with conceptual performance and ritual, the painting being the end product of his focused attention, even compulsion. “Total fixation activity—I admire that tremendously,” he says, of the paintings of Beat painter/collagist Jess Collins.

LG: The famous collage artist Jess hung a plaque in his San Francisco home that said “Seven Deadly Virtues of Contemporary Art: Originality, Spontaneity, Simplicity, Intensity, Immediacy, Impenetrability, and Shock” The contrarian post-modern spirit that Jess offers here interests me a great deal. Any thoughts to share about this? About Jess’ work in general, especially with regard to your own work?

John McNamara: When on the East Coast, I knew of Jess, but only his collages. I admired and identified with his process and complexity. But when I came to San Fran, in 1992, I saw his paintings, which blew me away, and I’m sure influenced me. His painting process was mind-numbing to me. I couldn’t figure out how he went about making the. I also responded to his personal and pop culture storytelling.

I didn’t see Jess as a postmodernist per se, but more as a quirky offshoot of painting’s long history. I saw postmodernism, on the East Coast, as a cool, detached, conceptually based activity. I don’t see Jess this way. I greatly admire him.

LG: I understand that you are a Professor Emeriti at UC Berkeley where you taught and lectured for many years. Some of your fascinating slide lectures are available to be seen online. (link to video series here) I love the surprising range of ideas and artists that you talk about in these lectures. In your teaching practice did you place more emphasis on studio practice like life-drawing, learning color, and other traditional painting skills, or has your focus more on theoretical concerns in artmaking?

John McNamara: For starters, I wasn’t a professor at Cal, but rather a “Continuing Lecturer.” Much less pay, and to some degree a lot less bureaucratic pain. The slide talks I gave, were part of a program called: Art8: Introduction to Visual Thinking. It was both the course that undergrad art majors had to take, as well as the Graduate Teaching Program. The grad students taught the classes, and I delivered talks on the various projects. I was responsible for mentoring the grad student instructors and keeping everything moving along. I photographed all of the images that I used in my talks, and there were many I shot with a film camera. I stressed the conceptual and intuitive aspects of art-making primarily. I also learned a great deal from having to put these talks together. Or maybe I should say relearn.

I did teach painting courses, where I taught more standard painting processes and material handling. I also was in charge of the undergraduate honor student critique session every Wednesday night. These were select students who had their own studios. The sum of all this teaching was that I learned a great deal from many of these exceptional students. Besides the art majors having to take the Art 8, students from throughout the university would take the course. And that was true of my painting course also. These students were from areas such as molecular cell biology, the philosophy and history departments, anthropology, and psychology departments. They brought their knowledge to my courses. And they made some highly interesting pieces.

Upon leaving, I commented that I had received a wonderful education! My forty-three years of teaching was a direct result of Joe Santoro stepping into my life and mentoring me. I made a promise while I was finishing high school, that if I ever could help somebody in the way Joe helped me, I would be there. So, when I started teaching while a grad student in 1975, I began to keep that promise. And, I never turned anybody away in those forty-three years of teaching. I don’t want any pat on the back for my efforts. It was a pleasure to be able to help people when they came to my office door or contacted me otherwise. That in the end, was my greatest satisfaction in teaching, people.

LG: How has painting been for you over the past several months? How are you surviving the pandemic, political turmoil, fires, and general craziness of the world?

John McNamara: Since March 17th I’ve been by myself, and except to go food shopping, don’t go out. I am 70 and suffer from asthma, so I’ve got to be careful. Otherwise, being able to paint each day has given me a sense of meaning in my life. It is a terrible time, for all of what you mentioned, and most people I know are in a similar state, a malaise, and anger, and just generally disgusted.

A few final thoughts: I started painting seriously when I was eighteen. I define that as making paintings for myself, and not for an assignment. Each summer, starting in 1968, until the present, I’ve focused entirely on making paintings/my work, for fifty-two years.

The most important facet of painting is: what are you going to make paintings about? Most people stop making art, not because their skills aren’t good enough, but rather because they have nothing they truly care about enough to want to make art.

Moments and Thoughts:

When I entered art school at 17, my first class was with Jeremy Foss. He told us that we were going to make our first painting, and it had to be no less than 4 x 5 ft. I had worked 3 x 4 ft, but this was going to be my biggest painting, and I knew exactly what I was going to do. I was going to make a seascape. This seascape I had painted many times, so many times in fact that I had it memorized. And boy, was it really going to blow everything in the class away! Ha, yes competitive.

But then, Jeremy said we couldn’t have any recognizable things in the painting. So that was the beginning of abstract painting for me! And so it went, back and forth between abstraction and figuration.

January 1984 – I had been making abstract paintings since 1978. My show at the Bess Cutler Gallery in NY, was open on March 15th. I took a call from her that Jan. night. She told me that the paintings I had made for the show would probably not go over well, since Neo-Ex was the only thing people wanted to look at. She told me that she was going to show my work regardless, but very little would probably happen. When we ended the call, I started thinking about how I had really wanted to make some figurative pieces but had pushed it back in my mind as being not feasible, and kind of jumping ship. But it was on my mind in a big way the next day. So, I made the decision to make an entirely new body of work for the NY show.

Below is an abstract painting I was going to exhibit in that show. 9 x 17′

Below are three of the figurative pieces I did between Jan and March 1984. Very large also, with a lot of figuration and painted photography. This was the first time I engaged photos in this way.

These paintings go back to the figurative/abstract fusion. Shown in NY – 1984. these paintings were the first to use painted over photography as an element. and they were large

detail view

detail view

It was nine years after making these paintings of 1984, that I finally settled on direct painted photography. I use now, as I did in 1993, a puzzle-like interlay of the photography. Below are two close-ups of the piece I’m working on now, without paint, and showing the puzzle-like interface.

It is odd, that such a well-worn historical process took me so long to arrive at. For the past 27 years I have followed this approach, and interestingly, haven’t felt the need to revise it. The last part of my artist statement has kept me occupied.

The content of my work focuses on conceptions of transcendence, moments in popular culture, and sharable life realities. I consider my paintings to be open, investigative narratives. My hope is to provoke a sense of curiosity within the viewer, similar to the curiosity I feel when making a painting. I strive to make a painting that has visual and conceptual engagement

John McNamara’s abstract paintings, those especially from the 1980’s, are incredibly beautiful and transfixing. There is a power of tension within that creates life. They are majestic and rich and transcendent. He’s been true to himself but growing all these years. Amazing work!

I meant paintings also from the late 1970’s.

Johnny McNamara was well known for his large works while he was a student at MassArt when I was there. He was, as many of his MassArt contemporaries would agree, a man with a plan. Great to see your successes over the decades, John. Didn’t you also exhibit at the Clark Gallery in Lincoln (Massachusetts)? My best to you and yours – Marie Rock