I’ve long admired John Goodrich’s brilliant landscapes for their clarity of color, economy of brushwork and engaging composition. He is also a gifted art writer and has contributed to this site with several reviews of shows in NYC. I recently asked him for an interview so we could find out more about his work, art writing and thoughts on painting. He recently gave a zoom slide presentation about his work at the Bowery Gallery as well as a solo exhibition in February of this year titled Descending Light. Goodrich explained the show’s title:

“For each motif I sought an embracing pictorial rhythm. All had to be energized: a rock’s huddling permitted a tree to stretch; clouds pressing the horizon released the plains below. Sunlight both illuminated and cohered. As I worked I often recalled my advice to students: express in color the “descending light.”

John Goodrich is a New York-based painter, teacher, and writer. His paintings have appeared in solo exhibitions at Bowery Gallery in New York City and the Contemporary Realist Gallery in San Francisco, as well as in group exhibitions at Elizabeth Harris Gallery, Kouros Gallery and Lori Bookstein Fine Art in New York City, and in numerous group shows around the country.

His work has been mentioned in reviews in The New York Times, The New York Sun, The New York Observer, The New Haven Register, and other publications. In the past he has taught studio art classes at the National Academy School of Fine Arts, the University of California at Santa Barbara, Long Island University, and Western Connecticut State University. He currently teaches at Haverford College and Borough of Manhattan Community College.

A writer on art, he was a regular contributor to Review magazine, The New York Sun, CityArts and Artcritical.com. He currently writes for Hyperallergic.com. Painting Perceptions.com and other online publications.

Larry Groff: Tell us something about what your early years were like and how you became a painter?

John Goodrich: I have to admit that in high school I liked record album covers with freaky beasts and flaming planets. Going to art school, moving to New York, and spending time in museums cured me of this.

All along I’ve enjoyed working with my hands. I spent some fifteen years as a cabinetmaker. I still find the decorative arts satisfying and continue to work as a graphic designer. Fonts are like a language in themselves. But I think the decades as a craftsman have only made it more evident to me how painting surpasses craft. I think many people involved in the arts want painting to be more than craft, and they sometimes look to concepts about painting, or to social issues. But for me, it’s the pictorial power of great paintings that lifts it above craft.

LG: Did your family encourage your interest in art or was that something you came to later on?

John Goodrich: They just wanted me to be happy in my occupation, whatever that might be. They did send me architecture books for Christmas, and in the 70s I briefly enrolled in a pre-architecture program. That didn’t work out very well.

LG: Who did you study with and what was art school like for you?

I studied in a number of places, longest at the University of California, but the most productive and inspiring school experience was at the Studio School in the mid-70s, where the energy level and sense of a mission was truly inspiring. It’s also where I studied with Leland Bell, who had a big impact on my understanding of painting and particularly the powers of color.

LG: Have you always painted representationally?

John Goodrich: Almost always, though I think representation and abstraction are just the end-points on a single spectrum, and every good representational painting draws continuously on abstract powers. A few times, mid-way through one of my classes, a student will say something like, “Why, this scene I’m painting is abstract!” and I want to say, “Yes. And welcome to that wonderful, fearsome world of painting!”

LG: How has your painting changed over the years?

John Goodrich: I’d liked to think I’m more focused than before. But the style really hasn’t changed at all, and unfortunately neither has the fact that a good deal of my time standing before the easel is still wasted, not for lack of trying, but because I’m not seeing clearly in the moment.

LG: I understand that Corot has been a big influence on your work. Can you say something about why that is?

Well, Corot was a remarkable painter, and with the possible exception of Chardin, the painter who most naturalistically transcribed the observed world, using all the muscularity and energy of a pictorial language. For me, Corot has a terrific mix of innocence and insight—the freshness of actual experience, with colors popping about under sunlight (quite a leap from Claude, where they vibrate within a program of color) but also a formidable awareness of how each form could be made to count and contribute to a coalescing whole.

He influenced the Impressionists hugely, of course, but more than any of them he seems to have “drunk from the draught” of the great painters. This shows in the way he so powerfully orchestrated, moving from energized masses to telling details. Clement Greenberg once described Corot as the “last great academic painter,” which is only supportable if you find all traditional painting academic. Not every painting by Corot is great, but even that big, fluffy cow-and-tree-and-pond painting at the Frick is remarkably muscular, once you get beyond its superficial charms of technique and imagery.

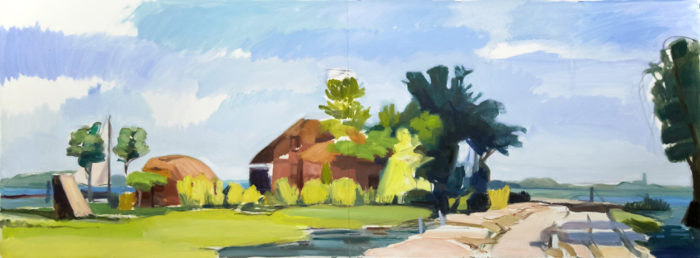

After Rembrandt’s Etching “Landscape with a Road Beside a Canal”, 60×22 inches, oil on Arches oil paper, 2016

LG: Can you say something about some important artistic influences for you and how this affects your work?

John Goodrich: Of all my teachers, Leland Bell had the best eye for painting. Though he didn’t make direct comparisons, he articulated better than anyone else the difference between the greater and lesser masters. He was also very inspiring — he had a remarkable way, in his museum talks, of making the great painters feel like fellow-travelers on a journey through colors and forms.

LG: What would you say determines the success or failure of your paintings?

In my best efforts, I saw clearly for a few moments, reached an intuitive understanding, laid in a few charged, broad strokes, and followed up with a few necessary details. And sustained this over the entire course of a painting. Joking! Actually, with the best, I understood something, and wrapped up a few inspired moments in a lively, if not always climactic, whole.

LG: How important is direct observation to your work? Do you primarily work on-site or will you work in the studio from drawings reference material or memory as well?

John Goodrich: Since all of our visual knowledge derives ultimately from the observed, I think visual experience is crucial to every visual artist–it’s our lingua franca. How could it be otherwise? When painting, I start from life most of the time myself and then rework in the studio. But painting is continuously a matter of inventing—you have to find a way to make a building really rise, just not sit there, or make a cloud truly hover, and this involves constant relational tweaking. I invent just as much outdoors as in the studio–it’s innate to the process of locating the “real.”

LG: How important is drawing to your practice? Do you keep a sketchbook?

John Goodrich: I tell students they should keep sketchbooks (and Corot’s and Delacroix’s and Rembrandt’s drawings are proof enough) but I no longer do myself. I find drawing to be maddeningly like painting, in that the results are autonomous and unpredictable, and for me neither really prepares directly for the other. For some painters like Bruegel, or van Gogh or Seurat, the energy of their drawing seems to lead seamlessly into the vigor of their color, but I haven’t figured out how to do this. Maybe, if I had several decades left, I’d begin to find a way.

LG: What is your painting schedule like? Is it important that you paint every day?

John Goodrich: I tend to paint in bursts—weeks devote to teaching and graphic work, then a spree of painting.

LG: Who would you say are your favorite living painters?

John Goodrich: A number of my peers, all of whom deserve more attention.

LG: Which of your art books do you most frequently look at?

John Goodrich: Rembrandt drawings. Seurat drawings. They’re some of the few things that make you wonder if color is really necessary. I’m convinced that no print or screen can really do full justice to a painting’s color—to the pressures that move the eye, at various speeds, to certain points.

LG: What artwork do you return to on a regular basis? What in particular keeps you coming back?

John Goodrich: The artists that I’d most like to see, once museums reopen, would include Giotto, Titian, Bruegel, Rembrandt, Chardin, Courbet, Corot, and Matisse. Veronese and Bonnard too.

LG: Besides looking at paintings what interests you the most visually?

John Goodrich: I try to stay amazed by the visual aspect of the world. One mental game I pose for students is to imagine living your whole life on a space ship, and then one-day setting foot on earth, with objects popping up at all distances, facing you from the various points where they’re glued to a great flat surface stretching away in all directions–and the whole smorgasbord illuminated by one glowing orb.

LG: How did you get your start with art writing?

John Goodrich: That’s easy—I was complaining about the state of contemporary art writing to my brother Chris, who was then writing book reviews for the LA Times, and he finally said (in kinder words): Stop whining and start writing. I’m grateful to Bill Bace, editor of Review, who first accepted a piece of mine.

LG: Did you study writing formally or is it something you taught yourself?

John Goodrich: I never studied art writing, and would like to think that each time the scope of the piece is determined by the visual impact of the art itself. I’m not a big believer in contexts of viewing.

LG: How did you get into writing catalog essays and reviews for the various leading art publications such as Hyperallergic.com, Artcritical.com, and others in NYC?

John Goodrich: My writing pace has slowed this last year, but overall it’s been hard work, resilience, and feeling comfortable inside that incubational space of writing.

LG: How do you decide on who or what to write about in your reviews?

John Goodrich: Editors’ assignments were a big factor. This past year, teaching commitments have really cut into my writing time. Even in ordinary years, the sad fact is that it’s often simply a matter of being free at the right time, in the right place.

LG: What are some of your considerations when reviewing a show?

John Goodrich: I like what Courbet said, something to the effect that he simply tried to describe his own time, based on a familiarity with great painting. Any painter that can do this is worth writing about, and also relatively easy to review.

LG: I’ve read that the jazz musician Thelonious Monk once said “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” How well do words really convey the experience of a painting? What can good writing about art offer us?

John Goodrich: I think we’re too dependent on words—and therefore on concepts and contexts. Or it may be the other way around–we fall back on words because we find concepts and contexts more accessible. Art history, a wonderful discipline in its own right, has supplanted, to too great a degree, our visual experience of painting. History explains the wonder of cultural trends, but not why Rembrandt was a great individual. What does explains this is the visual evidence left by Rembrandt himself, revealed first-hand, anew each time, in his drawings, prints, and paintings. It’s what’s in a work by Rembrandt, and not in a work by a student of his–say, the capable but less daring Nicolaes Maes. And words very imperfectly relate this evidence.

LG: Do you read much contemporary poetry? If so what poets interest you the most? What ways can poetry help a painting?

John Goodrich: I’m pretty illiterate when it comes to poetry. My suspicion is that music, and its entirely nonverbal gathering and relaxing of intervals, comes closer to the expressive core of painting.

LG: Do you have any thoughts about how the galleries will survive the economic and health crisis? What do you think the art world in NYC will be like once the pandemic is over?

My guess, if pressed, is that the art world will survive, though perhaps even more polarized between fast-lane international galleries and scrappy artist-run venues. My worst fear is that it will encourage the public to believe that an exhibition of paintings can be experienced on a screen. This would never be true of the paintings I admire most.

LG: Any thoughts on the future of painting education post-pandemic?

One great virtue of art is that the best education can be acquired by anyone who has access to a museum. My fear is that digital imaging technicians will someday convince curators that they can completely recreate the colors and textures of great paintings in digital reproductions. Just think of the savings offered by high-tech reproductions that don’t require high security or climate-control! Perhaps painting will be truly dead at that moment, at least as a societal experience. Until then, we’ll continue to be able to personally experience the expressions of the greatest artists that ever lived.

Leave a Reply