In the fall of last year I was lucky to get an opportunity to meet and talk briefly with Jessie Fisher at the Missouri Valley College at a group show I was included in. I was intrigued by many of the things she said and afterwards I found her website. I was enormously impressed by her work and decided to ask her if she would be willing to be interviewed by me. From her home and studio in Kansas City, Missouri, Jessie Fisher and I talked over Skype in March at the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic–just before she was about to leave for Italy to work on a fresco project, which then needed to be postponed. I am very grateful for her incredible generosity by sharing with us so much of her experience and insights and to give a glimpse into her intense engagement with painting.

In researching her background I was struck by a question Christopher Lowrance asked in his interview with her in 2016 on MW Capacity.

Christopher asked… “Are you conservative, or academic?”

Jessie replied: “… Rather than conservative, I see my work as subversive in relation to much of contemporary painting and see much of contemporary painting as extremely conservative. I consider the term academic to be a compliment, as I see this a type of authorship. One that is completely present in the awareness of its own making, while being simultaneously in command of its lineage. I see this sensibility dripping from the walls in central Italy and in painters like Titian, Corot, Bonnard and Balthus. Compositional and technical extravagance tempered with analytical rigor; painting about painting.”

Fisher expands further:

“…I do resist common, or current connotations of these terms because I often find they are used in a qualitative manner and that astounds me. To qualify a mode of consideration is limiting and additionally lays bare the fact that the critic is giving an opinion and not responding to the context of the work. Strangely apt to this question, my mother recently met John Cleese after a lecture where he was speaking about the creative process in relation to several books that he has co-authored on the psychology of the creative mind. His potent piece of advice, in addition to the fact that anxiety and distraction are the enemies of the creative practice, was that, ‘very few things matter and that most things don’t matter at all.’ What matters to a studio practice is a direct engagement with an unbiased and open process and not with current boundaries, definitions or camps with in a discipline. Too often, when a student defines the conservative in their work, I find that they are naming things they are avoiding based on the opinions of their perceived tastemakers, and where they see innovation, they are often aligning themselves with a current trend.”

“Jessie Fisher received her BFA from the University of Minnesota and her MFA, with a minor in printmaking, from the University of Iowa. She has studied at the Scoula Internationale della Grafica in Venice, Italy, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Fisher has been a visiting artist and artist-in-residence at the Visual Arts and Design Academy, Santa Barbara, CA, the Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in Maine, the International School of Painting in Montecastello di Vibio, Italy and Studio Art College International in Florence, Italy. Fisher is a recipient of the Ohio Young Painters Prize and a founding member of Studio Nong, an international sculpture collective and residency program based in southern China. Her work has been exhibited in museums and galleries in Minneapolis, Iowa, Ohio, New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Italy, and China.

Fisher is a Professor in Painting at the Kansas City Art Institute, a visiting critic in the Painting Department at the GuangXi Arts Institute, Nanning City, China and an associate artist with Studio Balma, currently preparing for work on a multi-year boun fresco project in Terni, Italy. Fisher lives and works in Kansas City, MO with the painter Scott Seebart, their son Valentine and their 8 cats.”

LG: What made you decide to become an artist?

Jessie Fisher: I was always interested in drawing, and although praised by others for rendering a likeness, I was unhappy with the results. I however did have a clear idea of what I thought the truth of art was from a young age. I remember, in what seemed like one day, my mother took me to the Walker Art Center and then to the Minneapolis Institute of Art to see the permanent collections. I was impressed by the formality of both institutions, but when we stood in front of the Institute’s breathtaking Lucretia (Rembrandt), I was viscerally aware that there was a clear distinction in art; between art as spectacle and art as visual poetry. We also went to the Walker at midnight to see the films of Andy Warhol which formed an image of the artist in my mind; one who was responsible for the orchestration of something that they themselves were absent from. The autonomy was very appealing. The inevitability of actually becoming a painter occurred to me when Scott Seebart, my partner of 30 years and an outstanding painter, had set up a studio in his apartment in our first years of college. He was so cool. While Scott was spending a year painting in Amsterdam, I changed my major from Architecture to Fine Arts and when he came back, we moved in together and set up studios in our apartment and I really felt like I had begun a serious practice. At the same time, I was fortuitously asked to work on a 3-year boun fresco project happening in Minneapolis. I completed my undergraduate degree through directed study credits working on the project, and that experience was pretty much the bulk of my undergraduate arts education. And now, over 25 years later, I am preparing to join the same painter, Mark Balma, in Italy for another large-scale fresco project at the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Terni, Italy which will start as soon as we are able to travel again because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

LG: The fresco artist, Mark Balma, in Minneapolis who you said you had worked with, did he take you on because of your drawing skill, and was this also an important part of your start to learning the figurative tradition?

Jessie Fisher: I was always drawn to figuration, ever since I had seen a book on the Sistine Chapel in my mother’s library when I was very young. My mother is a Dean at the university that commissioned the fresco project and she and I crashed a presentation that Mark was giving. We spoke after the lecture and he generously asked me to be one of his assistants. I had no formal drawing experience when I started the project, but I watched him very carefully. Working with him was my opportunity to see, hour by hour, figuration being developed through extraordinarily traditional processes. I was working with a group of older assistants who had a lot of training, and I realized, that as incredible as the experience was, I didn’t have any of the tools necessary to do what I was seeing being done. So, when the project was over, I applied to graduate school, realizing the almost complete lack of information in my undergraduate program. We had no life drawing or painting curriculum and a narrow range of what was considered essential information, like color theory, surface preparation, the morphology and science of materials, discussions of visual theory and precedent…so, when I applied to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts it was in hopes of finding a way into figuration.

LG: You likely chose PAFA because of its long tradition of figurative training but I’m surprised your early work at PAFA seemed more abstract.

Jessie Fisher: I wasn’t trying to be antithetical, but when I got to the Academy I found it necessary to make two bodies of work. I was looking at a lot of Italian painting and, as one does, was attempting to create life-scale multi-figure paintings in what I saw as the grand tradition of painting, and was hitting a brick wall in terms of my figurative skills and knowledge of materials. I also was very aware that the figures themselves dominated the space of the painting like disembodied sculptures with no relationship to each other. I started to look at paintings through a different lens. I looked at overall ideas of spatial recession and compression, at the way in which they engaged the picture plan and how their overall shape language made no distinction between animate or inanimate. I lined my studio walls with a continuous piece of canvas that was 7’ tall and began painting. I was making large-scale abstractions, the same size as the figurative works, where I could deal with ecology of forces: gravity/levity, near/far, physicality/void, sentience and unconsciousness through color, mark, and scale, without the aid of an icon. Around that time, I had a studio visit from a great critic at PAFA at the time, James Rosen. He entered my studio, took a long look at my room, and turned his attention to the wooden chair I had set out for him. He said, “If I were to ask you to describe your chair, you might have said it was hard, and possibly, that it was cold. If I were to pour water on the chair, you might have also said it was wet. But why, when I first asked you to describe your chair, you didn’t tell me it was dry?” His question and our talk afterward, along with the series of books I was reading at the time, Modern Painters by John Ruskin, were an epiphany. I understood for the first time how the activity of the composition conveyed meaning; how abstraction was the armature on which form was built.

LG: I’m curious to know more about why you left PAFA.

Jessie Fisher: I thought at it was a great program, and Philadelphia is a great city, especially for painters. Scott was there for 2 years, first in their Post-Baccalaureate program, and then both of us for our first year MFA and we became friends with several of the professors. I learned so much in terms of speaking about work, literary analogical structures to the image, and how precedent informed the category, or the context, in the reading and consideration of paintings. It was very influential to be surrounded by the range of work of the other students and to be part of its ongoing discussion, but there were no opportunities for teaching. One of the wonderful PAFA professors, Mark Blavat, invited Scott and me to be visiting critics in his drawing class at Temple University. I knew instantly that I was interested in teaching, so a large part of our decision to leave was to find a program where we could get some real experience. We took a year off and lived in a beautiful lime green micro-bus with a little sink and pop-top, visiting friends who were studying in other programs and departments and campuses around the country looking for both a wonderful place to live and a teacher/s that we wanted to work with. And that’s how we ended up at the University of Iowa to study with Ron Rozencohn.

LG: I understand the University of Iowa has an excellent writing and poetry program but I don’t know much about their graduate painting program. What was that like there?

Jessie Fisher: Iowa City is a beautiful and progressive city. Our house was built in 1854 by the Bohemians and had been restored by a local history professor. It was like a museum, with plexiglass windows in the thick lime walls showing the horse-hair insulation. It had never been inhabited by anyone other than the descendants of the original family of tailors who ran their shop out of what we used as our studio spaces. The writing program is awesome and attracts a lot of really interesting students from across the world. Scott and I were both accepted into the MFA program, and Scott started a critique group between the writers and the painters that were by far some of the best peer-to-peer critical discussions of our work we had there. The MFA is a 3-year program, which I think is a very beneficial timeline. We had incredible studios accessible 24 hours a day with a gallery in an old medical dormitory, graduate students were able to sit in on classes in the department they were interested in and chosen students were given drawing courses to teach. Scott and I had a year’s worth of credits from PAFA, and I had already taken several graduate-level art history courses outside of my degree requirements at the University of Minnesota, so we spent our time teaching, painting, gardening, attending the weekly departmental group critiques and traveling during the summers. It was a mixture of incredibly formative and positive development paired with on-going frustration. Teaching every semester, sitting in on Ron’s classes and our close friendship with him was invaluable, but our departmental critiques were another story. It was a night and day difference from PAFA where we had passionate discussions about a much broader range of work than what was being produced at the time in Iowa. Scott and I found ourselves in vilified as ‘painters of tradition’, making ‘paintings that looked like they belonged in a museum and not in a gallery.’ The critiques had little to do with the visual organization of the work, focusing on what was being said by the audience and not seen. One particularly beautiful spring evening we had a guest critic during one of my critiques, Deborah Pughe, a phenomenologist who was doing research at the time on drawings in the margins of scientist’s research notes. It was fabulous. She talked about what was happening in the work. She identified how the activity in the minutia of the surface and its arrangement within the painting’ boundaries created the condition we respond to inside of the making of the work. I vowed that if I became a teacher I would do the same.

LG: Well, I’m very interested to hear more about how you run your critiques or more about your criticism about how critiques are run. That is critical, especially these days when increasingly you hear about how they can often be more about a discussion of the story or meanings behind the work rather than anything visual that’s actually going on in the work. More and more you hear about how the emphasis is increasingly on art theory and less on studio practice in many art programs.

Jessie Fisher: Making paintings and looking at painting are innately theoretical activities. I think the problem is not the theory itself, but when theory and practice are considered separately. If a painting is at the complete service of theory and not born of itself, the work is an artifact, as David Hickey would say, ‘dogma for the King’ and I want painters to rule their own kingdom. What I find the most compelling and useful in drawings, paintings, sculptures, texts or films that I admire is how clearly you see the influence. When you can articulate how an artist is speaking to histories of medium and motif, you can identify where the artist is speaking in a personal voice within that tradition. Autonomy is born through an understanding of influence, not a dismissal of it. I ask students, always, to introduce their work to the group, to try to contextualize their current work as a tradition itself, a current point of view. Not as an explanation, but to speak on the broadest level about the ideas and material ambitions that they initially brought to the work and how these have evolved throughout the process of making.

Criticality is not an opinion.

LG: How much are you directing the structure of what your students study? Do you see your role as more to just help them discover the kind of painter that they want to be or do you have them all follow a specific course of study and direction they need to go in terms of getting a solid foundation of learning how to paint?

Jessie Fisher: All of the students have dedicated studio spaces and are creating an independent body of work from the first day of class that is fed through the year by an ongoing collection of synchronous lectures, readings, museum visits, studio visits, demos, painting sessions and structured assignments that can shift in response to the range of interests from each new group of students who I work with. I don’t separate what is foundational with what becomes their personal area of interest; one is born from the other. Students simply need to understand how ekphrastic languages activate their use of subject, that it’s not about learning a technique and throwing it on top of a personal icon. Identity and archetype can be recognized, but are meaningless unless communicated through material and visual metaphor. This integration of topics is structured to foster a close-knit and generous community of students who are intimately involved in each other’s studio practice.

Jessie Fisher drawing with students at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo credit Natalie Radermacher

LG: I’m curious to know more about this integration. Does the other faculty share similar ideas about teaching art or does there tend to be different camps? When I was a student going from one teacher to the next was like going from night to day with how they taught or what they thought was important or true in art.

Jessie Fisher: There is a similar situation in our department, for sure, but possibly the difference is that it is the ideology of our program. Each instructor is curated into our department to purposely create the broadest possible range of approaches to the discipline and use the structure of our program as they see fit. It’s as if each year in our program is like a small graduate school known for a particular material and critical focus. Its success depends on the strong precedent set in the sophomore year by myself, and the fabulous Corey Antis who I work closely with. While the sophomores are working to distinguish the individuality, self-awareness and autonomy of their studio practice, they share a focused discussion of craft, materiality, precedent, and perception. Students have their allegiances, which I think is necessary and healthy in defining a point of view.

LG: That’s good.

Jessie Fisher: Well, it sounds utopian but, ideology or not, the lack of consensus in fine arts education that you mentioned creates a situation that is systemically geared towards the individual. Its effects are polarizing and seem to intensify a double-standard. Certain approaches to painting are often held to a different set of criteria than those that approach painting through the expanded field because of a misconception, or mistrust, of what is considered traditional. When those issues creep into the studio it becomes divisive and often results in a painter becoming reactionary and isolated rather than feeling celebrated by a wide range of influences.

LG: You know one thing I keep thinking about with art school, you know that when students get out and then you’re faced with the real world, depending on where you wind up living after school, artmaking can be a completely different story. The skills you teach, strong representational skills as well as a strong understanding of the formal aspects of painting are often lost on non-art world “civilians”. The notion that you are trying to make visual poetry out of what you are looking at using the language of painting is often not understood or even on the table. What can you tell a student to prepare them for an art world that might not care about what you carefully taught them? Or is this not really an issue and they should just paint?

Jessie Fisher: It is an issue in that you do experience an inability, or unwillingness, to engage in a discussion of language rather than identity or biography. I think process is often misunderstood as purely intuitive rather than a nameable idea within the work. The gallerist and their patrons are generally not practitioners, so can you really expect them to truly understand where meaning truly lies in the work? I think it’s important to clearly champion the idea/s of making and seeing; the biography of the work and not of the self. Also, you should just paint. And, I would also say, forget about the real world, I certainly don’t want to spend any time there. My advice is to never dumb it down and to never conform. I don’t think painters realize how subversive their work really is, how powerful it is to see a show of paintings, how an independent voice is truly the embodiment of the avant-garde.

LG: Very good advice!

LG: Many wonderful and interesting painters sometimes fall into a situation where they get into a gallery, their work starts selling and despite never wanting to “sell-out”–the success with selling work, getting attention and finally being able to pay bills- could play tricks with their minds, rationalizing and distorting how they critically evaluate their work. I’m curious if you might warn your students about that? Also, how can they handle the knowledge that only a small percentage of people continue painting only a few years out of school because of needing to work at another job to support themselves?

Jessie Fisher: I think it’s possible to have a productive relationship with a gallery or an institution that is funding your research, but I do think the best scenario is usually when you’re not directly dependent on your work for income. The question of maintaining an objective eye and the willingness to experiment throughout your life in the studio is always a question, gallery, or not. After leaving the structure of school, the focus needs to be on maintaining a studio practice that is integrated seamlessly into the way in which you choose to live your life. It’s very important to remember that the success of your work is not in any way defined by its acceptance by the current institutions of art but rather a collaboration that the artist can decide to enter into. Whether you’re an artist or not, what you do for money should not be something that removes you from the life that you choose. In addition to art, Ruskin was a very active critic of industrialization and its horrific effects, not just on a worker’s economic status but on their quality of life, stripping them of the means for and the expectation that work should be purposeful, intellectually stimulating, and support the community out of need and not the corporate owner out of profit. Artists can be radical in this way. And I highly suggest falling in love with another painter.

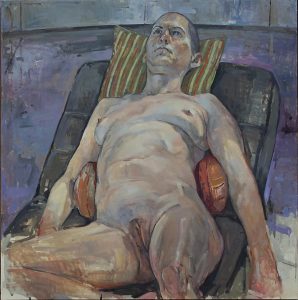

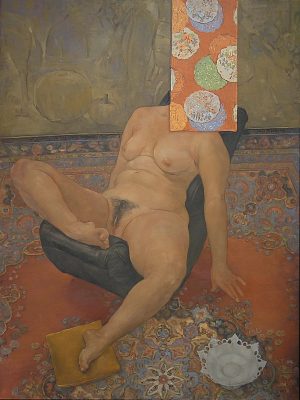

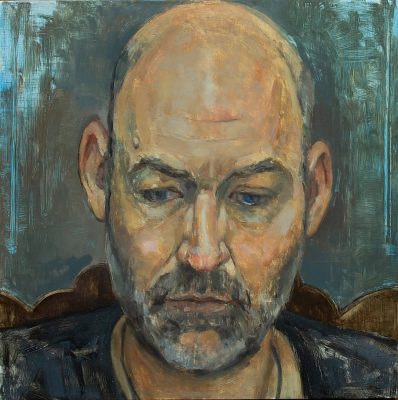

LG: On your website you have a number of involved, large, long-term allegorical projects involving the figure and then you have the smaller studies that are quicker or made in alla prima model sessions. I’m curious to know more about how you work with these different approaches.

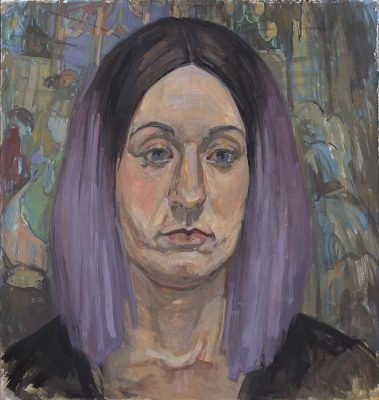

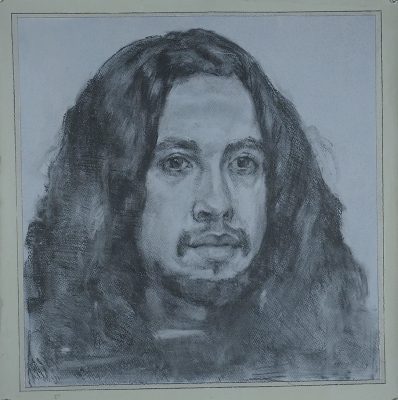

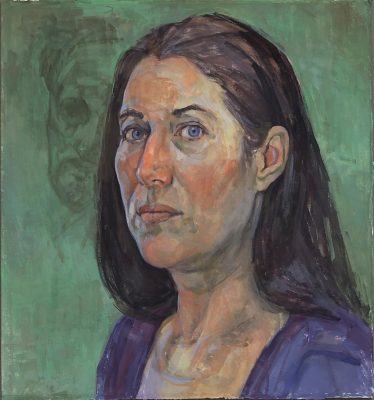

Jessie Fisher: I have run a Saturday model session at KCAI for the past 11 years where I work along-side the students and have used these sessions to play with materials and ways of working not usual in my studio. So, if this makes sense, I have used the Saturday sessions to challenge myself to be able to think indirectly in a situation that necessitates a direct approach. I wanted to use the alla prima not as an exercise, but as a way of thinking that has the possibility to be extended over a long period of time in the studio. Working with combinations of ink, casein, tempera gouache as an underdrawing for a final layer of oil, or on its own, has been amazing. I has changed the way that I am working in the studio, not just in terms of materials but in the way that I approach painting.

LG: I imagine how your casein and gouache works are similar to the buon fresco work that you that you’ve been involved with, you know, in terms of immediacy. There’s no way to go back and correct things so it must be an intense process requiring a great deal of focused concentration. Can you also talk about some of the things you are thinking about when starting a painting?

Jessie Fisher: A focused concentration, yes, but of a different kind. Working with those materials, I can approach the surface in a physical manner unimaginable in fresco and can edit almost indefinitely. More like what would be expected from a creamy and gestural oil painting. Typically, when I work over a longer period of time in my studio I am aware of the switch that occurs between drawing as preparatory and searching, and of painting as a way to play within the drawing’s structures. Because they are dry by the time I get to the end of my brushstroke, I am more experimental and intuitive, as my analytical eye tries to catch up with the speed of my hand. I am losing the distinction between the mindset of drawing and painting, they are becoming more and more simultaneous considerations.

The proportion of the picture plane dictates to a great extent how I begin. When starting a painting, no matter what combination or vigor of media I am planning to use, I am always very aware of the overall spatial ideas I want to work with. I want the dominant figural element/s to hang frozen on the armature of the structural divisions of the picture plane, and once that has been established, I can start to play with scale, repetition, arrangement, shape, and resolution. I think that might be the distinction between the sketch as a fragment with no presupposition and a picture as a guided consideration of the whole. I don’t find myself sketching very often.

LG: Are you saying you don’t have a firm preconceived notion of the direction your painting is going to go? Is it more about the discoveries your process reveals while working?

Jessie Fisher: It is definitely about a process of revelation despite very concrete ideas of what I want to play with in terms of composition and isochromatism. I don’t know exactly how they will manifest themselves, but I am always aware of what I think, at the start, will be the most direct approach. I love the ability of the painting to portray its flatness so what I am usually drawn to is an arrangement that begins with frontal pressure against the picture plane, a strong shape as well as a complex form. I don’t work with preparatory drawings because I prefer to discover these relationships in the real scale and real-time of the painting, and how it plays out is directly a result of reading the process. Quite often there are passages or compositional strategies from the painters that I look to most often that I am interested in incorporating into my image, or sometimes I take the entirety of an influential painting as the initial condition of the work.

LG: So do you keep everything you’re working to one area at a time? Or is your approach more gestural and work the whole painting as a whole, keeping it thin and build it up gradually in layers?

Jessie Fisher: When I’m painting, I have a clear focus on a specific form, or passage, that I am interested in building. To illusion of a form is more than its internal anatomy alone, it’s built through the object and how it creates analogies with all of its possible oppositions and repetitions throughout the whole of the surface. These relationships become attributes of that form, its visual persona. It’s very similar to how I look at paintings and what I think is essential to illusion. Nothing can be seen in isolation.

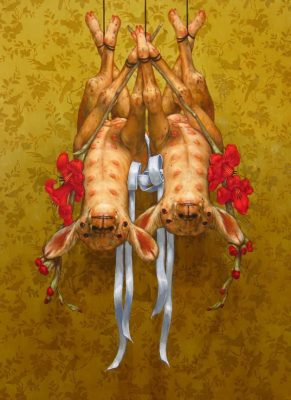

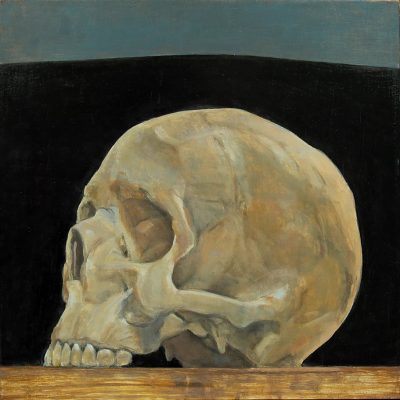

LG: I noticed that your painting’ subject matter seems to ebb and flow in degrees between being emotionally charged and confrontational or formal and subdued. Your portraits and figures, especially your small studies of the model are exquisite. But then we get to your allegories and nudes and especially some of your earlier works, like your still life’s with pigs and figures, are dramatically loaded in terms of the subject matter. Just as wonderfully painted but with a very different sensibility. I’m curious to hear about your approach to subject matter.

Jessie Fisher: I think of the subject as an extension of the language of painting, like a material that either makes its physicality known or disappears completely into the composition. In a way, I am really almost completely indifferent to the subject matter. I am more aware of how an object becomes a subject through the way it is personified by the painting: nude, portrait, emblem, tableau, still life. I’m not trying to negate the subject matter, but to dress the object in the guise of the painting. More and more, I am finding that, painting rooted in observation is enough to temper even the most dramatic of subject matter. Observation and embellishment are two extremes of a polemic that I am always considering, and I tend to land in a different place along the spectrum every time.

LG: You mentioned that you were planning on a new series of paintings, can you say something about what you have in mind?

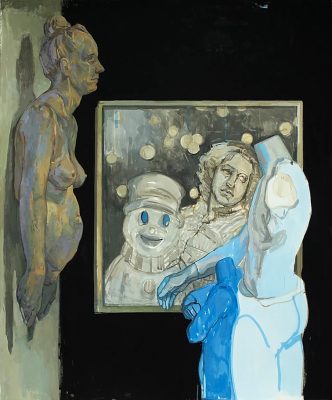

Jessie Fisher: Starting now, as a morning warm-up for a long period of uninterrupted days in the studio, I am sculpting a group of invented half-size figures and painting a series of watercolor monotypes of their progress, almost like my daily calligraphy. My main focus will be a series of larger canvases and works on paper, about 7’tall by 5-9’wide. Not only do I want to get back to working on a larger scale, but I want to specially work with melodramatic narrative possibilities of the inanimate. After living with a still-life painter for so many years, it’s starting to rub off on me. I will be setting up more elaborate scenes with life-scale figures, using my sculptures, amazing shower curtains, mirrors, a large inflatable aqua-blue pool, and some manikins that I recently found. I want to return to a sense of theatricality that I was using and some of my earlier work while keeping the painting rooted in the observational space of the studio.

LG: Like those wild still lifes with pigs, fruit and what looked to me to be dead babies from around 2007?

Jessie Fisher: Yeah, but not as emblematic.

LG: There’s a number of painters that come to my mind in looking at the whole scope of your work, but in these particular earlier works, Gregory Gillespie comes to mind. How he combined invention with the observed and the formal with the enigmatic subject matter. Few painters have interested me as much as his work has and I would love to see where these new works of yours might go.

Jessie Fisher: What I love about Gillespie is how linear his work is, how strongly he holds the contours that become containers for color and pattern. Gillespie’s images face the viewer, they are innately theatrical. He has images within images like Fra Angelico. Recently, I’ve tried to put a little bit of that recursive symmetry in my pocket and take it into my studio in a more overt manner.

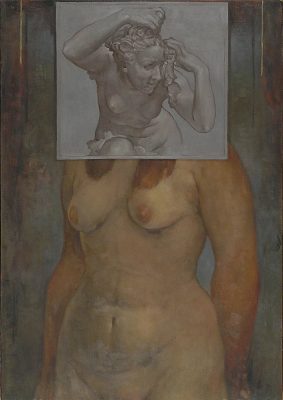

LG: Some of your recent figure paintings have the faces are hidden behind the artwork of some type, why is this? I’m curious about what you might say about how in some Philip Pearlstein’s figures the heads are cropped out and if there is any connection to what you’re doing with hiding the faces?

Jessie Fisher: I think of Pearlstein the same way as I see what’s happening in David Salle’s paintings, essentially both artists creating a dead image, creating equivalency in every moment, neutralizing hierarchy completely. I think if you cannot recognize hierarchy it becomes impossible to formulate narrative associations. Anticipation and expectation are what I’m thinking about when I place an object where one would expect to see something else, I am thinking of surrogacy, of structures of narrative possibility and not the telling of a narrative story.

I read that Pearlstein begins his paintings with a drawing on a sheet of paper a little bit larger than his arms reach so that he has no conception of the rectangle or the pressures between the mark and its edge. He works from the center out until he finds what he must consider a type of stasis. He crops the image and has a proportionate strainer created on a larger scale. So, essentially, he is finding the composition which results from but is indifferent to, his image; where the picture plane is an artifact of his drawing. I think that that’s an interesting idea in that it is almost the exact antithesis of how I approach composition.

LG: Talking about sculpture, I understand you have made a number of sculptures of the figure. Can you say something about how you got into sculpture and how it relates to your painting?

Jessie Fisher: I base a lot of my lectures for my drawing classes on sculpture and find myself spending more and more time looking at sculpture when I’m in the museum. For years I have been running an awesome elective class at KCAI where we work on-site in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art on long-term drawings and paintings from the sculpture collection. It’s crazy how a sculpture’s composition rests entirely within the boundaries of its form and with how complex it is to compose infinite profiles from multiple points of view never seen together at the same time. In sculpture, scale is a physical fact and that changes everything. I met BangMin Nong, a sculpture professor at the GuangXi Arts Institute, at a short residency where I was working with figure sculpture for the first time. He invited me to study with him in China and we started a fabulous gang called Studio Nong that has been more than incredible. If you ever want to humble yourself as a painter and improve your drawing try sculpting.

LG: So you think you could make maquettes as studies or as a subject for your painting?

Jessie Fisher: I’ve never gone the Poussin route, but I imagine would be extraordinary for my conception of light. I have used some of the sculptures I have made in recent paintings, but they weren’t sculpted specifically with those paintings in mind. I was able to spend some time last summer sculpting again with BangMin and the gang at his studio complex in the idyllic SanMin Arts Village, and this time I specifically sculpted an arm, from the shoulder down to the fingertips, to be used as a prop, held or worn by a model in upcoming paintings. It’s been fired and is ready to ship along with rubber molds of plaster sculptures I made during our last residency. So now I have to wait for my crate to arrive and for when it’s safe to travel again. I would love to spend a semester or longer there really focusing on sculptures that could stand on their own, which are more than props or studies. I am also now a visiting critic in their painting department so I’ll be back soon.

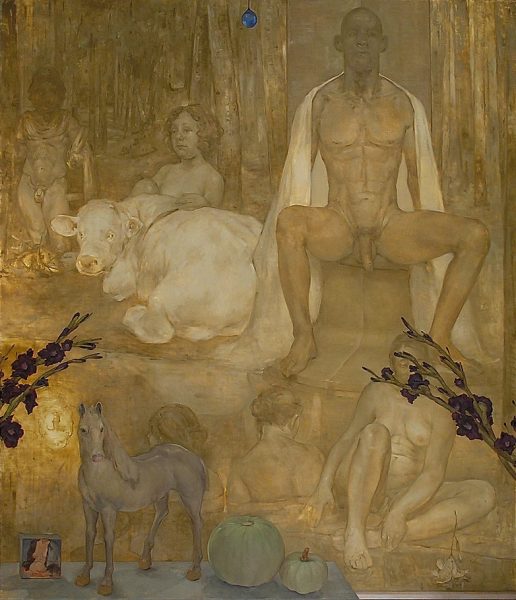

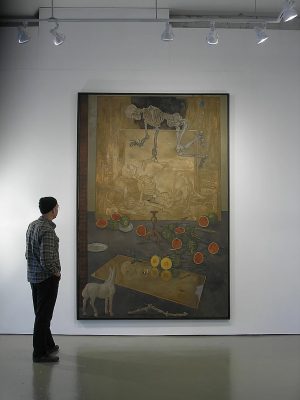

Still life with Sculpture,

installation view from the exhibition,

Recent Allegories and Nudes, Leedy-Voulkos Art Center, 2015

LG: Is it important for you to have the actual still life object there simultaneously with the model?

Jessie Fisher: I do work with the model in the exact interior set-up that she is posing in when she is in my studio, but when I am working on the painting in her absence, I don’t pretend that she is there. I work on paintings for many months to years, the light changes, the seasons change and my relationship to the iconography and possibilities of the painting changes. She could just as easily be removed from the painting as any other decision. Do you know Wilbur Niewald?

LG: Sure, great painter!

Jessie Fisher: When I first moved to Kansas City I was told that one role of mine within the department was to continue his lineage. I was invited to his studio where he took me by the arm and lead me towards a still life he was working on. He moved me into the exact position where he stood and said, “Scale is an idea, composition is an idea, subject is an idea… ideas have no place in painting. The only truthful experience is found when I am looking and responding. There is nothing else.” I thought that was awesome! I know that Wilbur would never work on something if the model wasn’t there. It would be anathema to put a mark down without being in the presence of the complete motif, for the same 2-hours of light, five days a week, over a long period of time. I am enraptured with his devotion to this idea. I thought very seriously about what he said, both in my teaching and in my studio, and came to the conclusion that what is essential is to devote yourself to constraint. Your constraint is a product of a singular practice, but it is something that binds you universally to other artists through a shared pursuit. I think this is also at the core of Wilbur’s outstanding influence as a teacher.

LG: I understand, that was also my belief for the longest time. As you may know my thoughts on that has changed more recently. I keep coming back to what someone once said to me, ‘how do you reconcile the belief about the purity of observational painting with the fact that most all the greatest paintings in all of art history have not been done directly from observation?’ Of course, they may have had studies and such from observation but that’s not the same thing as strictly working from observation. What would you say about that?

Jessie Fisher: It’s not observation or invention, its devotion that is pure. I think Morandi was devoted to observation, but I don’t think it was a rule. He is devoted because he is present. And then there’s the heightened, monumental artifice of Pontormo, drunk with influence. And then we are witness to Bellini’s sensualist evolution… What creates the transcendence of the greatest works ever made is the pursuit of a jewel that is only right in its setting, its ‘significant form’.

LG: I’m wondering if you make your own paint from dry pigments? How important is the more technical aspects of painting, especially with regard to your previous involvement, with fresco in your work?

Jessie Fisher: I love working with handmade and natural materials, I love stretching and preparing my own surfaces and go back-and-forth between using hand-made or pre-made pigments. I think Robert Doak does a much better job of making materials that I do, but with some recent handmade inks and some more viscous siccative oils I have been playing around with I’m hoping I can incorporate a little bit more of my own mixtures into my upcoming work. I have a collection of gorgeous pigments from Zecchi’s in Florence, and it’s a shame that they’re usually just sitting on my shelf looking pretty. I am so excited to be able to return to fresco on such a monumental project, as well as revisiting traditional uses of egg tempera and metal leaf in our secco decorations, and can’t wait to see what that does to my studio work. While we are working in Italy, Mark and I are going to set up a workshop and make some paintings according to his teacher Pietro Annigoni’s recipe/process for tempera grassa. I think that a lot of the paintings that we are broadly referring to as ‘oil’ paintings are really variations of grassa and this just might be the perfect medium. I can’t wait!

LG: Are there a lot of layers in your paintings? What are the surfaces like with your larger, long-term figurative works?

Jessie Fisher: There are a lot of layers in the painting but I don’t think it’s clear which mark precedes the other. I imagine the surfaces look very controlled. It might be hard to find a brushstroke broken by the topography underneath, but the paintings are anything but smooth.

LG: In these earlier works, they’re fairly thinly painted as well? Using layers of glazing and scumbling and things like that? Or had you previously been working more directly and with more impasto?

Jessie Fisher: No, I’m only ever the accidental impasto painter (laughs).

LG: Would you say that’s just your nature or do you just dislike paintings that are thickly painted?

Jessie Fisher: No, quite the opposite! When I see my paintings in my dreams they look like they were my compositions painted by Eugene LeRoy. Scott has incredible surfaces, similar to late Titian, with visible, broken strokes of paint, and there’s nothing more alluring to me as a viewer then those surfaces. And then there’s Bonnard, one of my favorite painters to look at, who at times paints so thinly that I almost have to hold my breath. But, what I think is common to all the surfaces that I love, is that physicality always remains integral to the logic a form. My drawing logic deals with almost indiscriminate shifts in levels of opacity, so I really do work with physicality, just on a very compressed scale. I am also limiting my palette to heighten the luminosity of the optical mixtures so you are always seeing one color acting as many, and although I work on my paintings for quite a long period of time they do remain relatively thinly painted with shifts in physicality both restrained and abrupt.

LG: Do you do sand down your painting to get back the transparency?

Jessie Fisher: No, for me sanding would be like going back into a previous state of the painting. Sanding would be like I was fixing something in the painting rather than developing my understanding of it further. When I lose control of the drawing, control of the opacity and refraction, I do find myself becoming a more direct painter on top of a very indirectly developed scaffolding.

LG: Are you saying that creates a tonal shift when you start paying more indirectly on top of something that’s built up with transparent layers?

Jessie Fisher: Yes, a dramatic shift between two completely different senses of light, and when it emerges it can be really abrupt. All of a sudden, the ground that has been so much a part of my understanding of the interaction of color disappears and I have to completely revise the way I’ve been mixing color. Suddenly, all of the relationships that I’ve been working with become out of whack, but that’s when the painting becomes something that is unknown, that’s when the painting really starts to becomes as strong of a motif as much as what I’m looking at.

LG: Do you ever find that the look of a painting changes too much from when seen from a distance from what you see up close? Where it looks great from 6 feet away but not so great from a foot or two away – or vice-versa? Any thoughts to share about how to finding balance between the two?

Jessie Fisher: I think about Titian and Antonio Mancini and how they are painting for a distance. An idea in the Renaissance, especially in terms of site-specific paintings in the cathedrals, is that the optimal viewing distance for the work was one-and-a-half times its height. It essentially asks the painter to consider three different compositions. The orchestration of scale, proportion, and design of the entirety of an image seen from a distance but which is constructed at the arm’s length of the artist. Each composition relies on the cooperation of the other, and much like different sides of the sculpture, are never seen simultaneously. And then there’s that’s perfect composition halfway between the distant and the near, where the viewer is able to see the logic of the whole but also discern the physicality and methods of drawing on the surface. The transitional distance, where both possibilities of the image, the macrocosmic and the microcosmic are available to the viewer simultaneously. A painting is a visual experience, like a 3-dimensional Yarbus eye-tracker. It’s thrilling. It’s terrifying. It’s something that could never be experienced without standing in front of the work itself.

LG: That’s a great way of saying it. I sometimes have trouble with photographs of my paintings work in that the painting looks fine on the wall from a few feet away but the photo looks all wrong, especially with smaller works. Too detailed and fussy – the image doesn’t come together, have the same sense of unity. There doesn’t seem to be any technical issues with the photo, the exposure and color are reasonably accurate, there’s no glare or noise and in focus. It just looks wrong on the computer monitor with all its warts and pimples that you wouldn’t notice in real life.

Jessie Fisher: I understand because a photograph has nothing to do with the experience of seeing the work itself. Vincent Desiderio said in a recent interview; that when you’re a younger painter your paintings look much better in the photographic reproductions, but as you get older, and your paintings get better, more attuned to the phenomenological and the atemporal, they will start to look worse in photographic reproduction. So, maybe it’s a good sign!

LG: That’s good to hear! It’s also tragic however. I keep hearing from people who teach that they have a hard time getting their students to go to galleries and museums to actually see paintings in the flesh, that left to their own devices will just look at art on their phones. More and more it seems people are making their work more on terms of how it’s going to be seen on a device than in real life. It becomes more like conceptual painting in a way, the sense of scale, surface poetics and the power of its objectness are lost on a tiny screen.

Jessie Fisher: I think that once an artist, or non-artists alike, has an experience of seeing a work of in person that is really provocative for them in some manner they will never again be remotely satisfied in the same way with the replicated image. When I take students to Italy where they are barraged with work that they have seen through reproduction, they are universally taking aback, shocked at how different the work really is when experienced in its true scale, and often in the environment that it was originally created for. When they return to the photographic after the experience of seeing the work in person, they understand the vast deficiencies of reproduction. I don’t think that someone that has had this experience can ever think that the image of the work that they see on the Internet is anything more than a placeholder. And this gets us back to what is this of primary concern within a painting; a physical and material surface that resists a finite temporal reading where all decisions have been made in response to scale.

LG: But you know, what can we do? At least there are teachers who are still teaching traditional drawing and painting and trying to keep it alive. People like yourself still teach students this way but it’s hard to predict how the future will play out. Sometimes when I’m feeling particularly low with all of this, I go to a dark place and start thinking that painting from observation sometimes feels like we’re making historical reenactments, like people going to Civil War Battle reenactments or musicians who only play archaic musical instruments, like early harpsichords or something, you know what I mean? But I know that’s not true, it’s something more primal, more fundamental and that’s what’s scary because you know, it’s such an important part of being human, having a visual poetics and understanding of the beauty of the world around you.

Jessie Fisher: Like you said, it’s fundamental, not elemental. The loss of the shared discourse of life drawing, painting, and sculpture are tragic. It’s like trusting the future of theoretical physics to scientists who have never taken a math class and who don’t want to sit next to each other when they do.

“There must be some, one quality without which a work of art cannot exist. What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto ‘s frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cezanne? Only one answer seems possible -significant form. …it is the one quality common to all works of visual art.”

Clive Bell, Theory of Significant Form, 1914

Great interview and wonderful work.

Nice post. I really like it.

Wonderful interview with a deeply experienced and knowledgable artist. Great work, but also great things to say about the structure and functions of painting. What a pleasure to read someone with such a rich background in painting. Wish I could see the actual work. J

Even though I worked on paintings and or drawings in the same studio as you, I didn’t get to realize or know much of what this interview talks about. I appreciate this article so much!

Alice Broughton

Fantastic interview with such high level thinking described beautifully.

Gives me hope for the future of visual art