I am pleased to share a recent interview with the painter and educator Jeffrey Carr that we discussed in person as well as by email. Jeffrey Carr is a friend and neighbor here in San Diego, where he moved several years ago when he retired from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia where he was the Dean for many years.

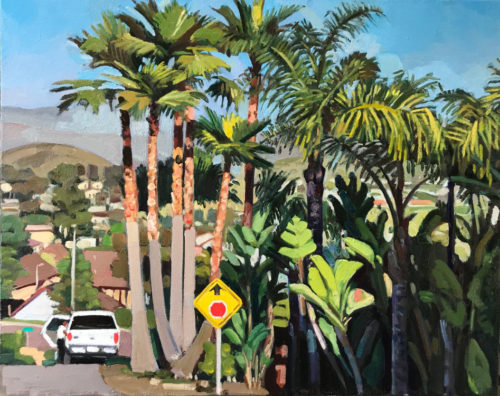

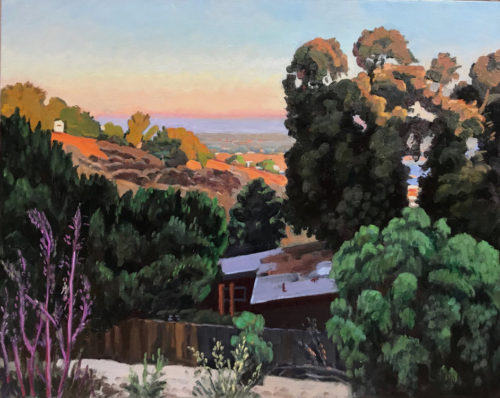

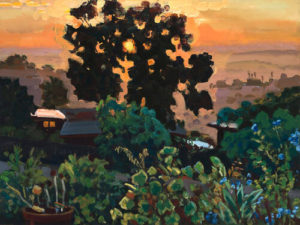

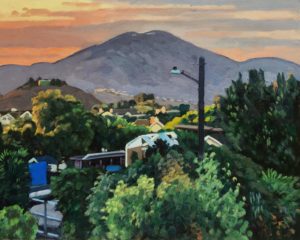

He lives in a delightful ranch-style home crammed with books, paintings and objets d’art. Down the hill from his house is a recently renovated structure converted to his studio which is surrounded by semi-desert vegetation on a hilltop that overlooks a vast semi-rural landscape framed by the nearby Mount St. Miguel. Partly-wild peacocks frequently stop by looking for food handouts but their plumage can’t compare to the color of the golden light across this vista at the end of the day. I’m lucky to not only get to know this talented artist, with great insights and knowledge about painting but also that I can share something of his art and story here.

Jeffrey Carr previously taught painting and drawing at a number of colleges and universities, including St. Mary’s College of Maryland; the Hope School of Art at Indiana University, Bloomington; Fontbonne University and the Herron School of Art at IUPUI.

He received his undergraduate degree from the University of California at Santa Cruz, attended the New York Studio School in the mid-seventies, and received an MFA in Painting from the Yale School of Art in 1979.

LG: What was art school like as an undergrad and as a graduate student?

Jeffrey Carr: My art school experiences happened in a different America and a very different art world. I was very lucky to work with a number of wonderful painters at the University of California at Santa Cruz in the early 1970s; Don Weygandt, Patrick Aherne, and Hardy Hansen were standouts. This was in the era of earth art, kinetic sculpture, body art, conceptual art, minimalism, Bay Area funk, and post-painterly abstraction. This is what I was shown in my contemporary art history classes and what I saw in the local contemporary art museum where I grew up in La Jolla, California. I remember an exhibition that featured an empty room with the sound of someone running very fast into the wall. Not much painting. So, at first, I tried very hard to be a good high modernist formalist abstract painter. I started out liking pop artists like Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg because I assumed that was way cooler than what I really liked, which was Baroque art, Impressionism, and nudes by Renoir and Gustav Klimt. I remember doing a “flag” painting with stencils, acrylic gesso, and cigarette butts. I did some “pour paintings” using dilute acrylic floated on raw cotton canvas. But I also liked Manet and the impressionists and did copies of Rubens drawings. So my revisionist tendencies revealed themselves early on.

My painting professors and one enlightened art history professor named Mary Holmes gave me a good introduction to the history of art and to contemporary painting that was very different than what was shown in the textbooks. Early on, I fell in love with French modernism. I was introduced to Morandi. I loved the eroticism of Viennese secessionist artists like Shiele and Klimt, and later, the expressionism of Kokoschka, Beckmann, and Corinth. I remember doing painting copies of Delacroix and Rembrandt and then, later on, trying my best to imitate Diebenkorn and Nathan Olivera. Along with everyone else, I was deeply inspired by the Bay Area figurative painters. Diebenkorn was good friends with my teacher Don Weygandt, and an enterprising student arranged for a show of Diebenkorn’s drawings. Park and Bischoff weren’t as well known in those days. This influence stays with me.

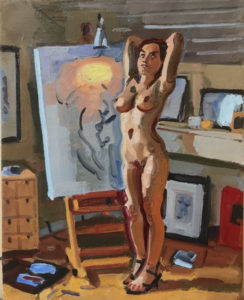

One of my professors wrote that I shut myself up in a little corner with an easel and taught myself how to paint. It was assumed you painted anything you want. In my case, I did invented figure paintings and various kinds of abstractions. I developed a passion for figure drawing. I never received any training in anatomy or any conventional academic training, but I tried to learn this on my own. One day I asked if I and one or two other painters could paint from a life model. We got a wonderful model with bell-bottom pants and a handkerchief on her head, and I was totally hooked on life painting. I still have those first paintings. It was as if I discovered who I was. I was told that I had to choose between these two approaches to painting; conceptual and perceptual. So I did. I’ve never gone back.

I wanted to do graduate school either with Diebenkorn at UCLA or with Nathan Olivera at Stamford. I admired an older classmate who had gone to the New York Studio School. So after living in Berkeley for a year after graduation, I went to New York to attend the Studio School. This was in the mid-seventies, and New York was very grungy and beat up. The Studio School was filthy, ambitious, sophisticated, and wildly energetic. Drawing was worshipped, as were the painters of cubist inspired French modernism; Giacometti, Derain, Balthus, Braque, and the rest. We all drew from models many hours a day. The critiques and the visiting artists were excellent. I studied with Andrew Forge, George McNeil, Leland Bell, Mercedes Matter, and many other amazing artists. Leland Bell, especially, was a major influence. His talks in front of paintings in the museums are legendary. In Leland’s class, I did a copy from Corot’s Grecian Woman in the Brooklyn Museum. In New York and later in Boston, I attended talks and critiques with Philip Guston. The so-called “New Realism” was in its ascendancy in those days, and I was deeply influenced by Fairfield Porter, Paul Resika, Paul Georges, Lennart Anderson, Alice Neel, Gabriel Laderman, Neil Welliver, Rackstraw Downes, Nell Blaine and all the rest. This sensibility is still with me today.

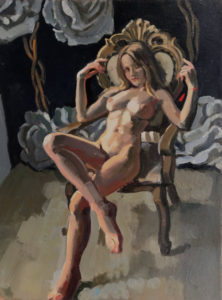

After a few years in New York, I went to the Yale School of Art and studied with William Bailey, Bernie Chaet, Al Held, Gretna Campbell, and others. Yale was a vibrant and competitive place. I was part of a small group of figurative artists. We took the lead from Bailey and did conceptualized and invented figurative painting. I attended William Bailey’s life painting class twice and had to give up a teaching fellowship to do so. Bailey’s class was among the most formative experiences of my life. He combined direct painting from observation with an abstract and formalist approach to design, color, structure, and space. The famous Newsweek cover of a nude by Bailey came out in 1982. The article was about the “new realism”. To me, this approach combined traditional subjects like the nude, landscape, and still life with a contemporary, formalist sensibility. The subject matter may be a street, an egg, or a woman, but the content was how it was painted, not what was painted. The modernism in the art history books was about successive “movements” of art towards some reductivist ideal. This other approach to painting is timeless. Cezanne, Piero della Francesco, Morandi, and Guston all inhabited the same kind of painting world; there was no real art history or stylistic development.

LG: What did you do after school? Did you start teaching right away?

Jeffrey Carr: I wanted to teach very much. I couldn’t think of any other way to make a living and I admired my own teachers. I taught at Pratt for a year before my soon to be wife and I moved out to St. Louis to teach at a tiny liberal arts school in St. Louis called Fontbonne. Later I taught at some small art schools in Connecticut and then for several years as a visiting professor at Indiana University, Bloomington. I then taught for many years at a small liberal arts college in Southern Maryland called St. Mary’s College of Maryland before becoming the Dean of the School of Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Philadelphia is a very artist-friendly city, and it has a long tradition of figurative art. I had a number of shows in Philadelphia over the years, and have many wonderful friends there.

LG: You painted from observation for many years – how important was that for you?

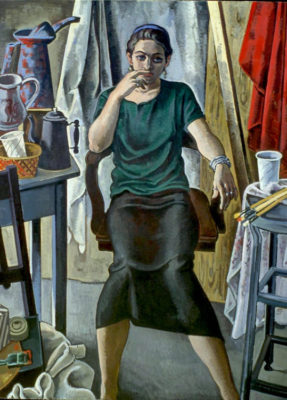

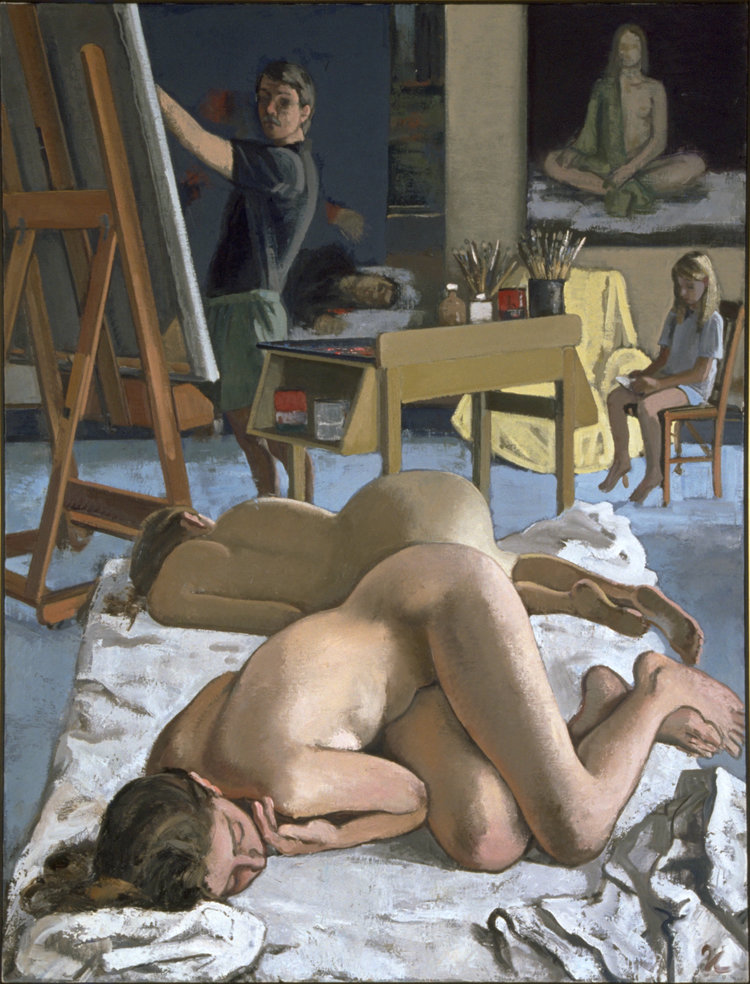

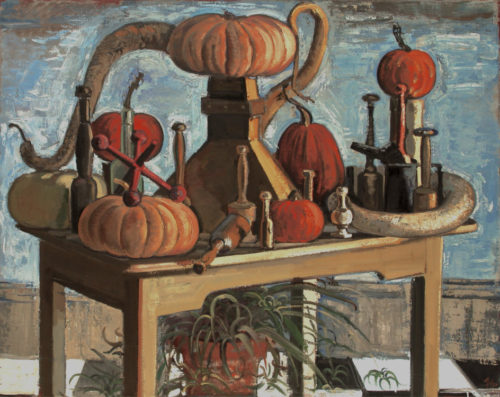

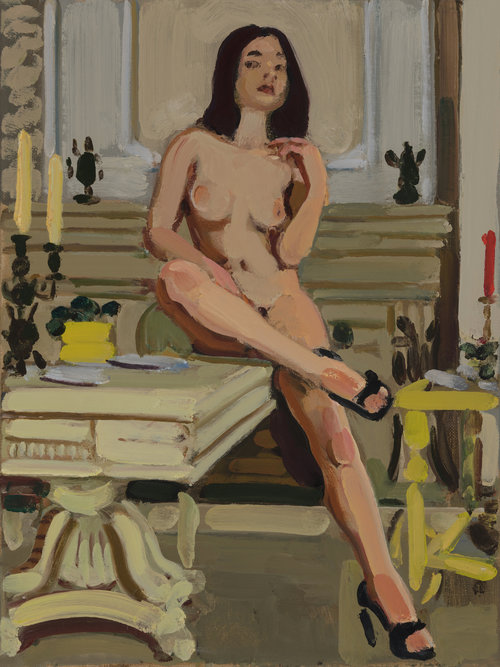

Jeffrey Carr: I have painted from life for most of my painting career. I would experiment with this or that kind of invented painting, but I always came back to life painting. If you paint from life, you have a limited number of options. You can paint from still life, interiors, self-portraits, landscapes, or models. I painted from large still life setups and from nude or clothed models. I did lots of self-portraits. I did landscapes only occasionally. At that time, I liked painting big, and it’s difficult to paint large landscapes if you are committed to doing them outdoors. I have a friend who does huge paintings outdoors, in Italy. I don’t know how he does it. With a still-life, you can sit in one place and then spend a long time arranging the subject in front of you, which is very convenient.

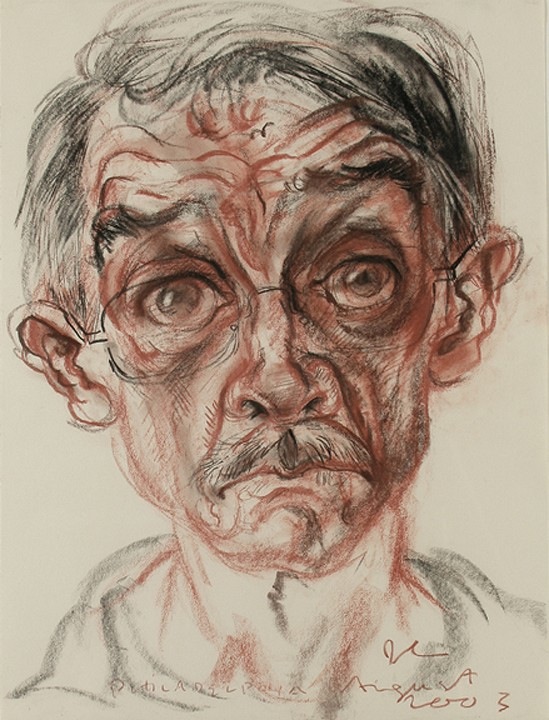

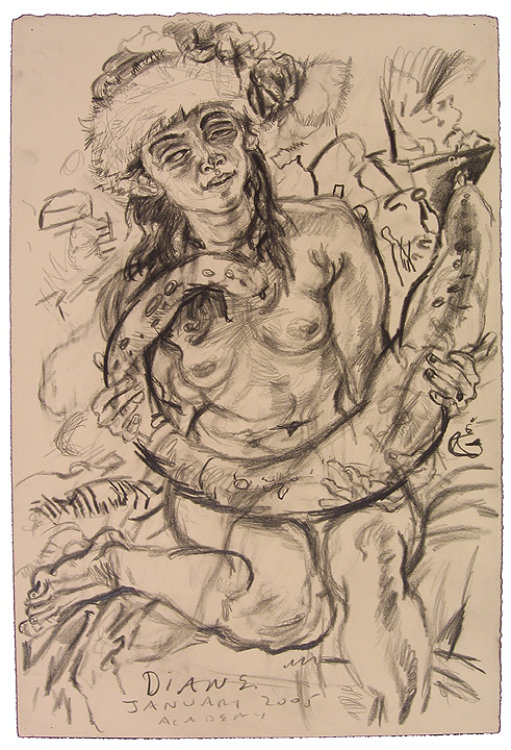

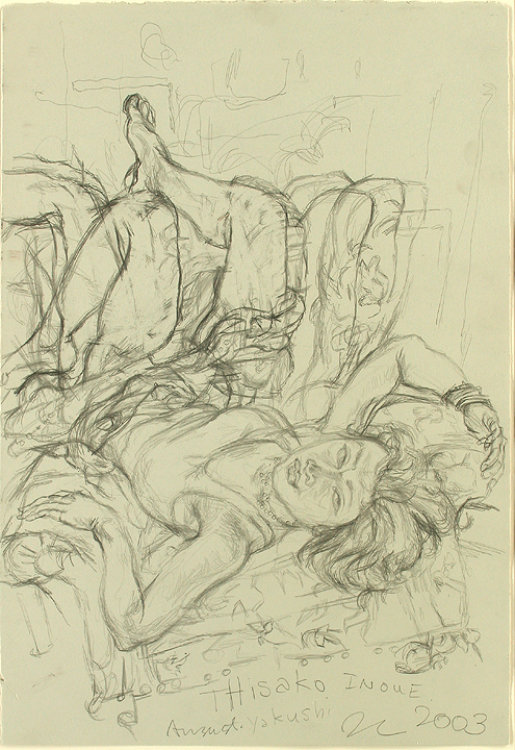

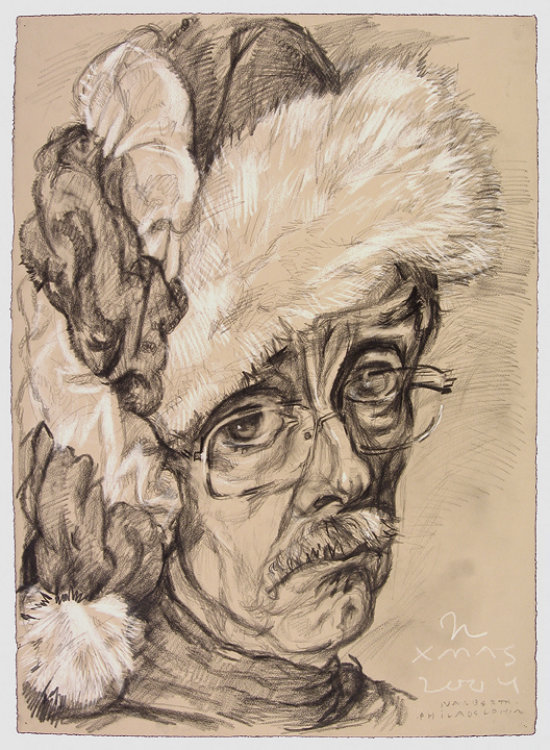

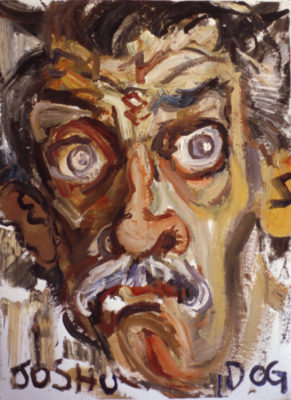

Drawing was central to my practice, and I especially love figure drawing. I love figure drawing for its own sake and treated my drawings as equal to my paintings. My models were very important to me. So were a number of great draughtsmen; Matisse taught me all about value and Ingres taught me all about contour. I did self-portraits when I couldn’t draw the model, and still life when I didn’t have anything else. When I moved to Philadelphia I did a series of big self-portraits that I think are among my best work. They are all oversize and expressionistic. I had in mind those Kokoschka portrait drawings and the Japanese tradition of oversize, expressive faces called Okubi-e.I painted from the model for almost my whole career, and my sensibilities are based on it. A good working relationship with a model was essential to the process. Painting from observation is about discovery, while painting from imagination is about invention. Painting from a model is both. The give and take of working with a model is thrilling. You get all the paints and the props ready, the model shows up, you fuss for a long time with the pose, the props and the lighting, and then you paint like mad until you or the model is exhausted and the time is up. Then you scrape down the day’s session, leaving a painting “skin” for the next time.

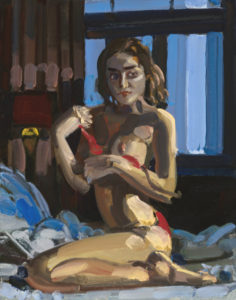

If the model is an artist, we talk about art. If not, we talk about them. The energy the model puts out ends up animating the painting. I am still in touch with a number of my models, even after twenty or more years. The active participation of the model in the creation of the painting is vitally important. It’s a collaboration. It’s challenging and exciting to be painting a living person in front of you; interacting with them, trying to stage something meaningful, working with their own psychologies and physiognomies. There are people who are wonderful models and some who just don’t seem to be able to “project” a persona to paint. You can’t tell ahead of time. I think it must be like this with actors and actresses. People have crazy or silly ideas about models and painters. I remember someone commenting upon a portrait I did of my wife. This person thought my wife was frowning and asked if we had had a fight as if a painting is the same as a snapshot. A painting is not the same as a person; it’s like a character in a movie. This should be obvious, but it isn’t.

LG: What were some of your biggest concerns with your still lifes and figure painting with your earlier work with regard to both subject matter as well as how they were painted?

Jeffrey Carr: The large-scale figure paintings came out of my love for painting from life the way Manet, Courbet, and Corot did. In our times, we have Freud and Uglow. I can admire artists who work up from sketches and studies, and who paint “in a series of operations” as Degas put it. Balthus is the last grandmaster in this tradition. But that is not my approach.

I like painterly painting, but I suspect that my figurative work from this earlier period was far more descriptive and naturalistic than my work is now. I liked working directly on the canvas; drawing with paint and developing the entire image while scraping down in between sessions. I painted many alla-prima smaller paintings, but the large ones took many sessions. I don’t work from preliminary drawings. I orchestrate the whole surface; composing the rectangle. I’ve seen how Freud works, starting in at one point and slowly adding all the rest. I could never work that way; I always worked over the whole painting at once, focusing on areas of value and hue and building up detail and form in subsequent sessions. I rarely glazed or underpainted. In the large paintings, I scraped down between sessions to leave a skin that I could paint into again. I rarely made big changes once a painting got far advanced.

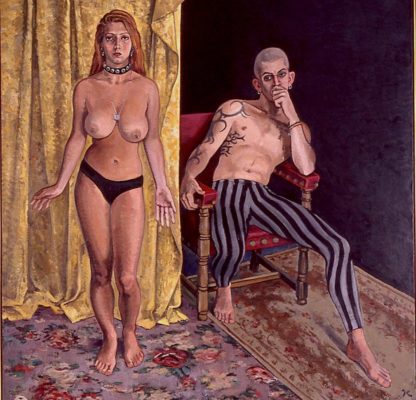

I worked with whatever clothes, attitudes, and personal qualities the model arrived with. I liked to include mythological or literary themes and art historical references. I sometimes used costumes suggested by the models. I remember drawing and painting one young woman who looked magnificent in an elaborate handmade 19th-century gown. One couple I painted as Shiva and Parvati; he with striped leggings and tattoos; she with a dog collar and enormous breasts. The son of an English professor posed as a hunter with a gun and a handmade skin hat. Once I was painting a guy with an afro, and then he showed up with a shaved head. He asked if that was going to make any difference. The same guy was working on his tattoos as I painted him; I had to keep adding more and more tattoos to the painting.

LG: You also painted many still lifes, what were some of your concerns there?Jeffrey Carr: I liked still life because it is pure picture making. I see a distinction between painters who like to depict literal appearances and those who like the abstract qualities of the set up in front of them. For example, Chardin is about overall tonal and shape relationships; his contemporary Jean Baptiste Oudry is about rendering visual appearances. One is about composition; the other is about arrangement. They are two very different aesthetics. But I am not an abstract painter; I still like illusions of form. What can be more challenging than painting flowers? Or the surface of metal? Or fur? My still life and figure paintings incorporated tongue in cheek references to mythological or philosophical themes hinted at with my titles. My still lifes had visual references to cityscapes or landscapes with figures. They were my attempts to do multi-figural compositions like what I admired in the museums. I wanted to suggest figures, machines, buildings, smoke, monsters.

LG: What thoughts can you share about the influences other artists, such as Bonnard and Matisse, have had on your painting sensibilities.

Jeffrey Carr: I’ve already mentioned many of them. They are the artists that all painters like. The work of Bonnard and Matisse is about pleasure and desire, which are important themes for me. The work is about joy; about grasping after something beautiful. They paint a universe of feeling and poetry. I’ve read quite a bit about both of them. Both lived through terrible personal tragedies; the death of Bonnard’s spouse led to those astonishing late bathers. Both Bonnard and Matisse survived the second world war. Matisse’s daughter was interrogated by the Nazis. But you don’t see the war in their paintings. I admire them for that.

The female figure was a central organizing principle for both of them, as it is for me. It’s an internal ideal; an emotional connection to the feminine forms of Psyche or the Anima. It is about Eros, rather than Thanatos. It’s life energy. It is “Luxe, Calme et Volupte”. This is my basic impulse as well; this is what the nude and the landscape mean to me. But I’m a friend to Death, too. There is Beckmann and Guston; both great tragic painters. And Bonnard’s last paintings of his spouse, Marthe, floating in her bath, are profoundly tragic. The tragic sense of life is complimentary to a profoundly optimistic one. You can’t have one without the other.

LG: What about Bonnard’s landscapes? Is there a connection to your work?

Jeffrey Carr: Bonnard’s landscapes are inventions, based more on memory and imagination than what he saw in front of him. He worked from his notes, from the memories of his walks, and from imagination. To my surprise, I’m finding that this is the way I work now. I’m working indirectly, from the computer screen. I think of myself as being true to life; judging the greens, the browns, and the blue-grey very carefully according to what I see. But I’m working from a computer monitor and from memories of my daily walks through this landscape. It puzzles me. I don’t quite understand how it works. I remember a Bonnard quote to the effect that the presence of an object is a distraction to the painter at the moment of creation. Is that true? I’m not sure if it’s true for me. But I know that I could not paint the way I do now if I were painting directly from the landscape.

Bonnard has the most amazing attitude towards shape. He is willing to go just about anywhere with it. I remember that famous picture of his with a girl looking at the head of a dog emerging from below a table, like Godzilla confronting the cherry pie. The head of that dog is painted several tones darker than the rest of the painting, so it contrasts with everything else. It makes no sense, but it’s wonderful. Who else can do that? And look at the shape of the trees in a Bonnard. It’s always a surprise. Whenever I am painting trees, I have that example of Bonnard to inform me.

My landscapes are based on value relationships. A supreme colorist like Bonnard or Matisse spent many years with low saturation and tonal painting in their early work. Bonnard is the only painter I know who can get away with ignoring value relationships. He can make space and form without relying on value; just on saturation, hue, and placement. Value is an extremely mysterious thing. Rembrandt would lower the value range of an entire figure to make a pearl glow. Corot’s figure paintings are like that. Corot’s amazing color is value-based, like Morandi’s. But Bonnard and Matisse can work with full saturation hues; often with little mixing. Matisse once bragged that he used just a few colors, right out of the tube. There is that amazing Cobalt violet light pigment that they both use full strength right on the canvas. And this beautiful pigment called Rose Garanche; again, right on the white canvas with no mixing. I’m in awe. I can’t do that.

LG: What more can you say about how your earlier work, such as your figures and still-lifes, differ from the landscapes you are involved with now?

Jeffrey Carr: I think my work from years ago was certainly more tonal and perhaps more naturalistic. It was more accidental, in the sense that it was based more on a direct response to what was in front of me. My work now is more deliberate, invented and premeditated. It’s less about accident or improvisation. That said, I compose with my IPhone. I frame up a scene very carefully when I photograph it, and take many photographs and choose between them. I modify the image a bit with exposure, value, and sometimes the hue. I’m sketching with the camera. But I don’t think I could have done this with traditional photography. Like everyone else, I spend many hours a day in front of a computer screen, and this has become a normal way to see.

My work now is much more about color than it ever was. I scrape and repaint until all the colors make one color; one enveloping sense of light. I’m a little amazed at how many colors are on my palette. I think I had eleven greens at last count. And I use all of them. Each of them feel like an entirely different hue; the way all the instruments in an orchestra may play the same notes, but sound entirely different. At the same time, I mix a great deal. I use very good quality paints, and a lot of alkyd medium to make sure they all dry evenly. I use a lot of earth colors and pre-mixed demi-teintes (half-tones). I think I’m much more conscious of the mark, of drawing the form with paint. The smaller scale makes me aware of this. I try to clarify and to simplify; to state the shape and color more directly and clearly. I want to keep the mark open, expressive and surprising. I like making a big mark of exactly the right hue, so that it falls into place perfectly. I like making space with color alone. I think I’m much more conscious of creating light and luminosity from relationships of tone, temperature, intensity and color weights.

LG: I understand that at some point it became difficult for you to paint during the years you had the position of Dean at PAFA, can you talk about what happened and why?

Jeffrey Carr: For a dozen years, from 2003 until 2015, I was the Dean of the School of Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Before that, I had been a college professor since graduate school. It’s easy to love teaching. You get to talk about something you love to a lot of interested people. As a younger professor, you can identify with the struggles and triumphs of your students. As an older professor, your students become like your grown children. It was painful to stop teaching when I became a Dean. The Academy is a wonderful art school, and I am deeply sympathetic to its aims and goals. But being a professor and being a Dean are two very different things. I had assumed I would continue to teach as Dean, but I was just too busy.

Being a Dean gives you a lot of life experience and a much larger perspective on yourself and on people. But it also makes it difficult to have the mental space and focus that artmaking requires. I remember the day I was painting and got the call to another urgent meeting. I never finished that painting, and that was the end of my painting for over a dozen years. I continued to do large drawings for a year or so more, and then I lost that too. It was very painful for me to lose painting and then my drawing. I’m sure other Deans can do it. But for me, I could not be both a Dean and a practicing artist.

LG: How much did this period of not painting pose a challenge to you when you decided to resume painting?

Jeffrey Carr: When my wife and I retired out here to San Diego, I had assumed that my artmaking life was over. I had destroyed a lot of my work, and I had given away all my still life objects and my books. I thought I would pursue my interests in meditation and Buddhism. Then my wife got sick, and I spent several years taking care of her and another sick relative. Within a month after her death, I experimentally got out some old paint and brushes. I found something on the internet that looked interesting to paint. I started up. That was over two years ago. I’ve painted nearly every day since.

LG: What has it been like to return to painting again?

Jeffrey Carr: It is joyous. The passion came right back. I was a little stiff and awkward at first, and I started small. But the touch came back online automatically, like an old software application starting up. There were many surprises. I realized that a much smaller scale is perfectly comfortable for me. Years previously, I had painted 50 inches or larger and did drawings mostly the size of printmaking papers. Now I was doing 12” by 16” to about 18” by 24”. I’ve been slowly moving up in scale. My current figure paintings are now 18” by 24” and my landscapes 24” by 30”. There are now paintings all over the house, as it is with most artists.

It’s just glorious to be painting again; like being reborn. But the stranger experience is working from a computer monitor. I find that working from a computer screen is a perfectly congenial and inspiring way to paint. And I don’t currently work from models. I work from images I find on the internet. It is not ideal, but it works until I can find a better solution.

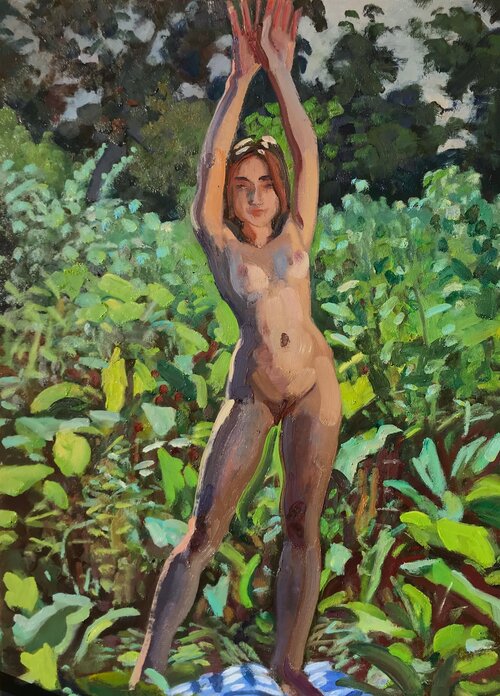

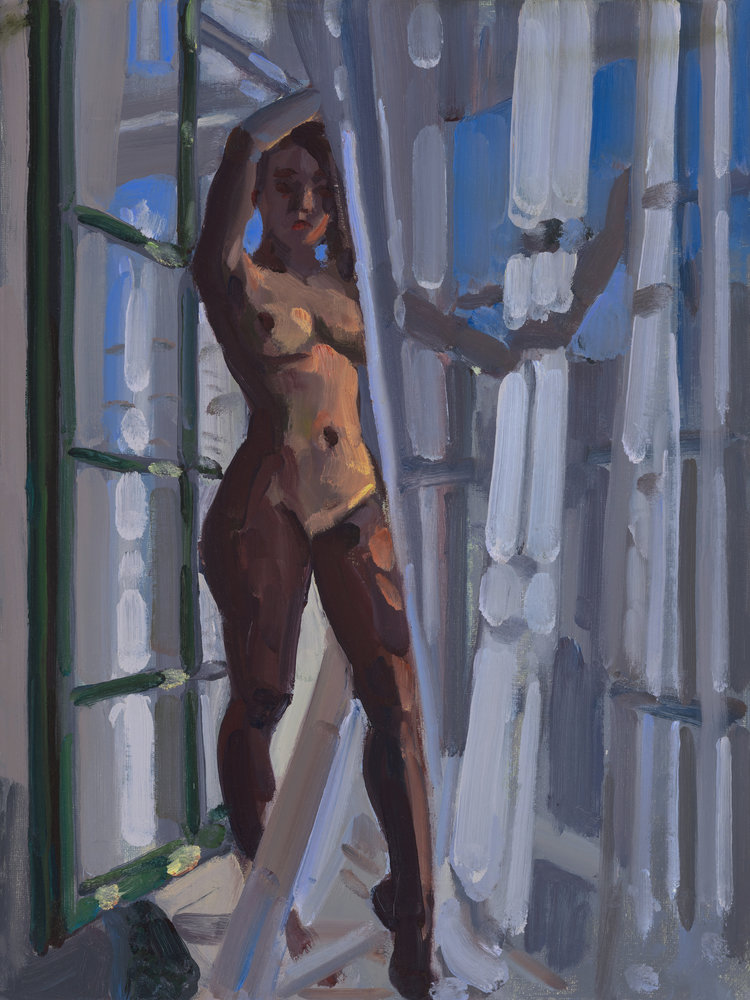

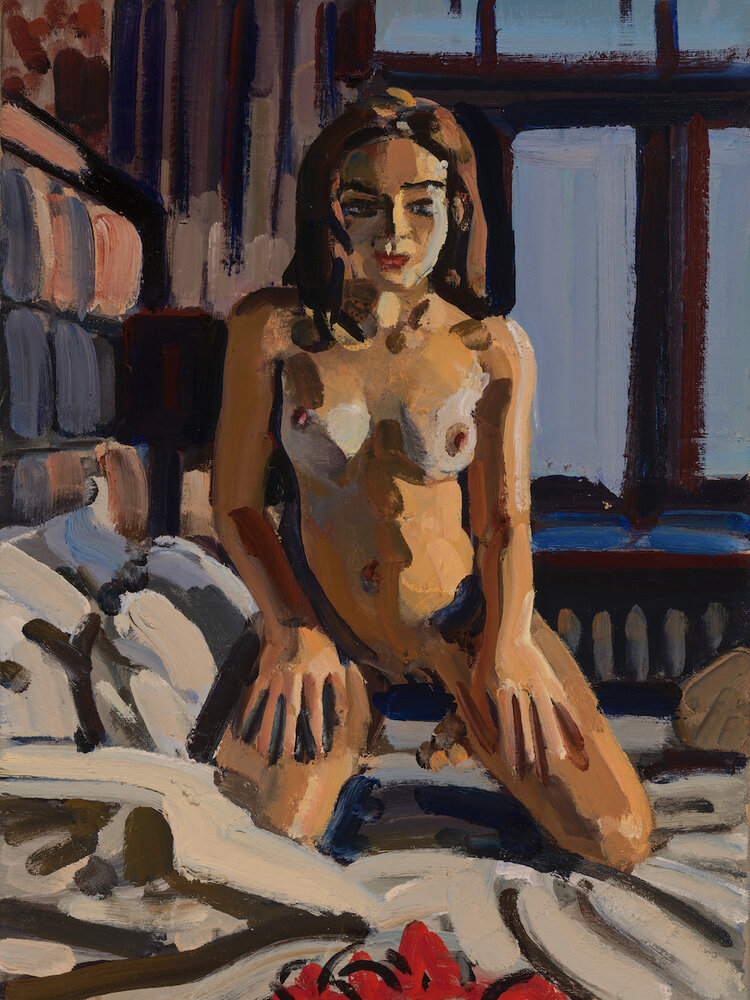

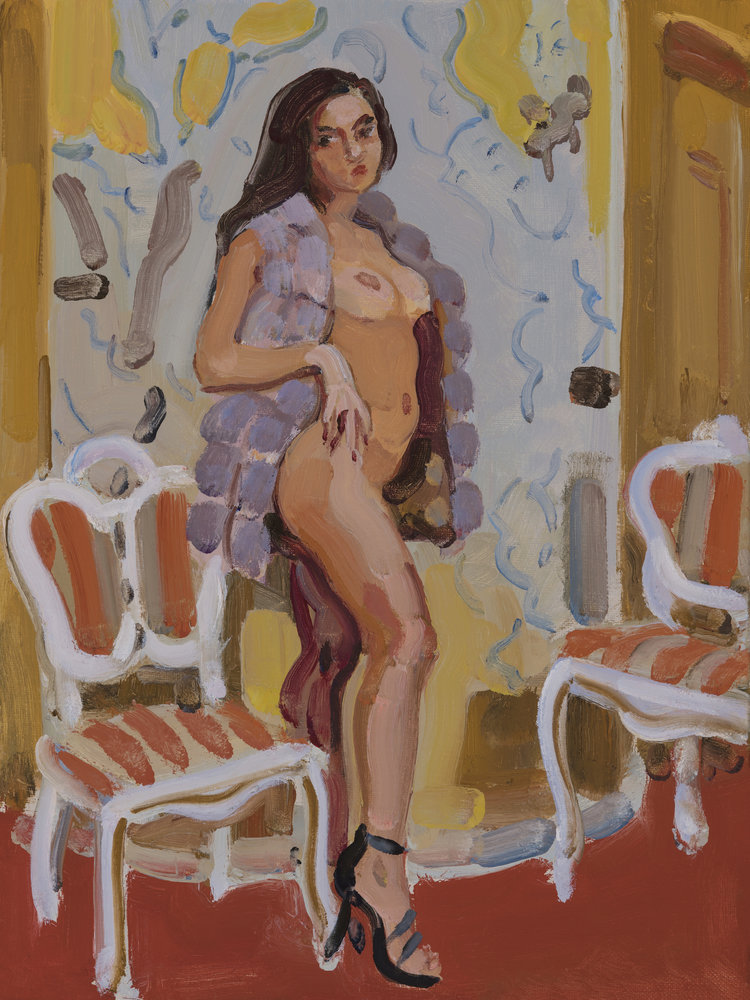

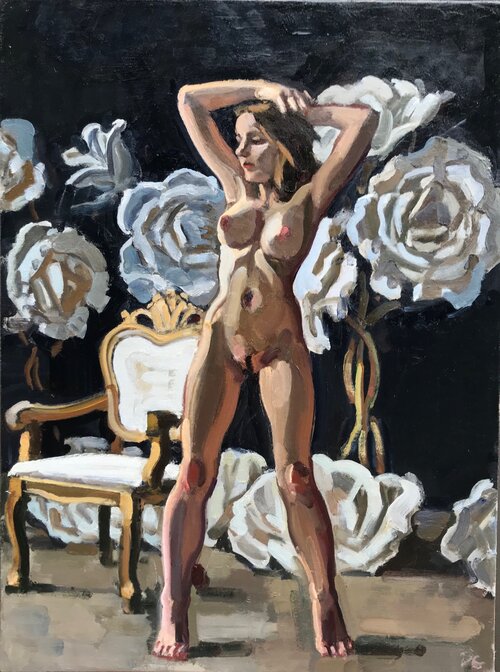

The subject matter of my new paintings couldn’t be more traditional: the landscape and the female nude. As subject matter, it is neutral. But it allows me to paint the way I want to paint. I am painting in the only way I could paint; it’s not a conscious choice. It’s a relief actually. I can’t change who I am. I used to think I could.

I’m concerned mostly with color now. The landscape has unleashed that in me. It’s the California light. When the painting is off, or lacks energy, it’s always because I didn’t look closely enough. Many painters past and present whose work seems wildly inventive had the motif in front of them all the time. Matisse said that he was entirely dependent upon his models. And Cezanne always painted “sur le motif”, even though his pictures don’t look at all naturalistic. Euan Uglow minutely records the colors and tones in front of him, but the result looks like Euan Uglow more than the model. That’s exactly the way I want to paint; the more it looks like the landscape or model, the more it looks like me.

LG: Can you speak about what you are trying to get at with your new figure paintings?

Jeffrey Carr: I love figure painting, and for me this has come to be nudes from photographic images. The nude figure is a perfect combination of drawing, color, improvisation, invention, discovery, sensuality, form and light. It is figure drawing with paint. I’m aware that the nude is controversial, and it should be. A person with clothes on generates specific content. It is always a portrait of a certain person in a specific circumstance. A person with clothes off can either be a portrait of a naked person or a nude with a more universal context. The nude can mean all kinds of things. But to me, it is a sensuous and beautiful formal device. I admire a number of modernist artists who have the female nude as a principal subject; Bailey, Anderson, Freud, Balthus, Uglow and many others. I see my nudes in this context. I like a lot of the nudes done by current artists. Many contemporary artists use the nude in a tragic context; to paint the body as a metaphor for sexual exploitation or satire. I use the nude as an expression of sensual delight and joy.

The female nudes I do now have traditional references to physical beauty, sensuousness and a kind of ideal. The photographic source material I am using also rely on these references. The nude is a formal device that demands careful attention to drawing, structure and color. You can change the shape and color of a still life object and it won’t matter much. But if you place a head not quite correctly on the shoulders, it looks all wrong. At the same time, the nude allows for a lot of latitude with expressive drawing. You can exaggerate the length of an arm or the shape of the body, because all bodies look both different and the same.

Painting flesh also allows a lot of invention with color. If you paint a tree blue it is just a blue tree. But to make a blue figure convincing, it requires a lot of adjustments with the other colors in the painting. I’m working on a series now of the nude outdoors, and I’m painting the flesh tones blue or violet against the lime green of a landscape. The trick is to make the flesh tones look natural. As Delacroix said, I can paint you a Venus with the mud from a ditch, if you will allow me to choose the surrounding tones.

LG: You’ve been painting from photographs but previously painted from life – can you share some thoughts about how this change has been for you?Jeffrey Carr: I had used photographic references in the past in a minor way; to paint animals or a landscape around figures painted from life. But I took it on faith that I was a life painter. As I started to paint again, I had the leisure to think about what I was to paint, and how. I thought a lot about the subject. Fantasy? Tantric art? Still life? Self-portraits? I have a prejudge against painting that looks exactly like photographs. But lots of artists use photos as a reference. Many painters I loved, like Vuillard or David Park, did paintings from references or invention that had the “feeling” of actuality. I realized that all painting is invention, really. One of the first things I painted was a face from the internet. I found I could do it easily, and that it felt completely natural. So if it works, then why not?

LG: Are you painting from a model?

Jeffrey Carr: I love painting the figure, but I don’t have models at present. So I’ve been painting from images I find on the internet. They are not ideal, since the poses and situations are stereotyped and I would prefer to set up the pose and the setting myself. If I could, I would try to make my own photographs- but then, I would have to be a photographer. And I paint now in a little studio, without the space or access to models I once had. When I painted and drew from life, the best models were art students who understood what I was doing. I miss that experience. But at the same time, I can’t quite see duplicating it.

The nude is a magnificent subject to paint. De Kooning said that oil paint was invented for painting flesh. With these new paintings, I am invoking specific connotations with art historical traditions of the beautiful nude. They also depict the cultural stereotypes inherent in the reference materials. I am taking familiar and stereotyped images and trying to paint them in a surprising way. There’s a cheekiness to the nudes I’m doing now, a slightly humorous or camp quality. This just comes with the territory. I think that Matisse’s nudes have a camp quality. Some of his cut-outs have Josephine Baker and her famous banana dance as a subject.

LG: What are some concerns you might have about painting the nude today?

I have been questioning many of my own assumptions about the female nude. There was a recent exhibition here of Bouguereau and his nudes. In school, I was taught to hate these paintings. And it is true I prefer Courbet or Corot. But is this because of the subject matter or the way that they are painted? Since at least the sixties, the subject of the beautiful female nude has been universally celebrated in popular culture and universally denigrated in fine arts culture. Pearlstein, Seville, Yuskavage and many others have painted the female nude as ironic, formalist or as protest images. The amazing nudes by Lucien Freud have come to set the accepted standard for the high art nude. Freud’s nudes depict the body as tragic or grotesque. By contrast, Balthus is hated for his images of sexualized children, but I have never seen more beautifully painted nudes. I see some evidence that younger painters have come to again celebrate the beautiful nude. I hope so.

While I like the associations with sensuality and feminine beauty, I don’t want to paint sex. There are many contemporary artists who use the nude as pornographic or sexual reference. I’m not interested in portraying pornography. Of course, the nude is sensual and can be seen as sexually provocative. Well, all beauty is erotic to a greater or lesser extent. A sunset is visually thrilling and evocative; it’s erotic in the sense of being sensually arousing. A beautiful nude can be even more so.

Many years ago, I was in the Met, drawing that spectacular Courbet of the Woman with a Parrot. After a while, I became aware of a little old nun giggling at me in a knowing way. I couldn’t figure it out at first until I looked up again at that magnificent image of the model Jo Heffernan, who posed for a number of artists including Whistler. Well, she got the little nun going and she gets me going too. Life is full of disappointment, limitations, and suffering. The female nude can celebrate joy, sensuality, and beauty. If it provokes or alarms, so be it. It is intended to praise.

LG: What are you trying to get at with your latest landscapes?

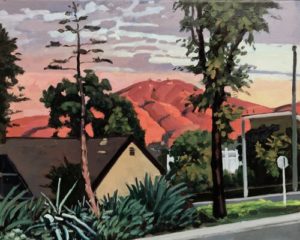

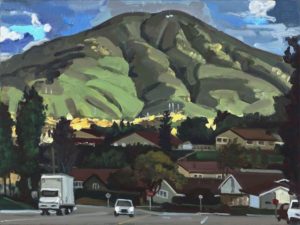

Jeffrey Carr: I love the color and light of California. I’ve never felt this connected to a sense of place before. The light of California has liberated my color; as it did with all those French painters from Delacroix to Balthus whose color was liberated by the color of the Mediterranean. And of course, there is Diebenkorn, Park and the rest. It’s the Diebenkorn color. I grew up here, and have waited all my life to return here. I live on the same property I grew up on, with the views of that mountain, St. Miguel, that I paint over and over again. I like the “bones” of the landscape; the geometries and contrasts of houses, streets, trees, hills and sky. I paint the scenes I see every day on my walks. I’m best with the subject matter I see every day. When I paint a landscape I’m not so familiar with, I can’t find the scale, color or the light that I want. Robert Hughes calls this kind of color-based landscape painting, “The Landscape of Pleasure”. That’s it exactly.

The image on a computer screen looks fundamentally different from a drawing or a photograph. It is luminous, so you can get a better suggestion of the color. And you can crop and enlarge it. You can choose from among lots of related images. In some ways, painting from a computer monitor is easier than painting from life. There’s not that much information there, but there’s enough. I combine what I’m seeing on the screen with memories of my daily walks. With a computer image, I can take my time. I repaint a lot. I can afford to look and think about it.

I have many friends who paint directly from the landscape. How do they do it? There is the wind and sun to worry about. And dogs, and visitors. When I used to work outdoors, I could only work my painting for an hour or two before the light changed too much, and I had to hope that the light and weather were more or less the same the next day. And the palette was too small for more than about twelve colors. To paint larger or more extended paintings, I had to look out the window; and that means being stuck with the same scenes over and over again.

LG: In the past, much of your work seemed focused on drawing, especially figure drawing and your work seemed more tonal in focus. But now you seem to use color in ways to suggest light and space. Your color shapes and rhythms perhaps play a greater role. What are some thoughts you have about this process?

Jeffrey Carr: There are many narratives I was taught about the development of modernist art. One narrative is about the discovery that color has an expressive power independent of subject matter. Delacroix said that you should be able to judge the subject matter of a painting from across the room, from the color alone. The impressionists created an all over a network of color relationships, not a depiction of naturalistic appearance. And the fauves and the Blaue Reiter artists pioneered the expressive use of color for its own sake. Another narrative is that the 19th century interest in pure landscape leads ultimately to abstraction, through Cezanne and Kandinsky to Abstract Expressionism. I think of myself as a modernist through and through, even though I know full well that this is now an historical style that most contemporary artists have abandoned.

It is the color, rhythms and arrangement of shapes in my landscapes that create the sense of light and space, not the recording of appearances. It’s easy to say that this is true of all painting, but that’s not really so. A lot of contemporary art is about the creation and manipulation of images and associative content, not about the way color, shape and arrangement create space, form and light. There’s depicted light, and then there is the light that is immanent within the painting. This light within the painting is generated by the interaction of pictorial elements, not an illusionistic recreation of light falling on an object. It’s two different approaches to painting. One comes out of fauvism and abstraction, the other out of naturalism and realism. Both are part of modernism, but my interest is in the pictorial language that is essentially abstract. That is, using subject matter as a vehicle to explore a more purely visual language. It’s old fashioned, but I don’t mind.

LG: Who are some contemporary painters you find most interesting and why?

Jeffrey Carr: There are so many that I can’t list them. One thing I love about the internet and electronic media is that I can see so many of my contemporaries. In the old days, I got exhibition cards and the very infrequent mentions in the art press. Now Facebook and Instagram brings me images constantly of artists new to me or whose work I haven’t seen for years. And everyone has a website, so that I can look up artists effortlessly. I am constantly reflecting on my own work and its relationships with the often excellent painting by contemporaries that I see on the web. I feel much more a part of an arts community than I did in the days of seeing the occasional show and getting those cards in the mail.

I don’t mention my friends and contemporaries but I feel a deep kinship with many of them. I don’t mention names because I don’t want to leave people out. It’s too easy to cause offense. Many years ago I was sitting in a large room down on the Lower East Side, at a meeting of the Artist’s Figurative Alliance. Gretna Campbell was speaking about her work, and somebody in the audience asked her for her opinion of a contemporary artist. We all leaned forward to hear her response. She begged the person not to mention the name of a contemporary artist, because of course everybody would start giving opinions and judgments and the whole place would dissolve into an uproar, which it frequently did. Finally, the person shouted out- “It’s Soutine!” Gretna gave a huge sigh of relief and said, “Oh! I thought you meant a CONTEMPORARY artist! I love Soutine!” And everybody settled down.

LG: What are your thoughts about the future of paintings with regard to the pandemic and trying to establish a career with painting?

Jeffrey Carr: With the pandemic, we all stay home more and so there’s more time to paint. That’s good. Beyond just painting, what does it mean to have a career as a painter? To me, it means to make paintings and to have them seen and acknowledged by other painters. This is to have a reputation among peers. I think Facebook and the Internet has made this possible as never before. Among all of the horrors of this pandemic, we can be thankful for that.

LG: We talked many times, often sharing our worries about the possible gloomy outlook for painting as a career choice these days. Galleries have always had a tough time surviving previously but now with the pandemic and economic fallout it will likely be sometime before the selling and showing of paintings return to normal. Can you speak to this concern?

Jeffrey Carr: I’ve never developed much of a gallery career, so I don’t have a direct experience of how the pandemic has affected those artists with gallery careers. I imagine the pandemic is a disaster for anybody running a business that depends on getting people to a certain place for a certain activity, like running a restaurant or a gallery. But I’ve never really accepted the idea of having a gallery career. We were all taught that this was the ideal; having the gallery in a major city, having the sympathetic dealer who promotes your work, having a one-person show every so many years, building up the devoted body of collectors and all the rest. A few artists have that, but the vast majority of us don’t. And frankly, I don’t think it works very well for most of us.

It’s a lot of fun having your opening and seeing all your friends show up and say nice things. And It’s also nice if you have press. But a paragraph in a magazine or a newspaper doesn’t go very far. I much prefer putting a new painting on Instagram or Facebook and having old friends and new friends see them and respond. You can argue that this is not the same as seeing the actual paintings. That’s true, but how often is that possible? For most of us, when we had a show we got a group of our artist friends and occasional curious visitors to see it, and we hoped for a collector. But that was only for a month every three years or more. And in only one location, so that few people actually saw it. Most of the time, our friends got a little booklet (that we often pay for) or a little card. And we would look at the little booklet, and then put it on a shelf and that was it. But it made us feel like artists. And then, you might end up having your opening during a blizzard, as happened to me once. Really, is it worth it?

LG: Also, having been an art educator for many years, do you have any predictions on how the teaching of painting in art schools will fare going forward?

Jeffrey Carr: Well, I really hope it does go forward. Developing a personal relationship with a culture of painting requires a long involvement with a sustained community of artists, art patrons, galleries, museums and a cultural tolerance and understanding of the enterprise. That doesn’t happen in very many places. Painting as a culture is very fragile. I’m tempted to think it is in danger, but I see dozens of good contemporary artists online. So in some way the enterprise is thriving.

Maybe I am saying this because I’m an ex-art professor, but I think going to an art school is essential. Art school should be both an introduction to painting culture and training in the craft of painting. To develop a sophisticated eye, you need to look at a lot of painting both good and bad, and you have to interact with a lot of artists. This includes your peers, your professors, and to practicing artists. A great artist/teacher will change your life. Study with a couple of them, and you’ve learned the profession. It is true that art school is too expensive and inconvenient, and that there is no good teaching job at the end of it. But I think it’s how most of us become artists.

LG: Do you have any thoughts about how painting can be taught online?

Jeffrey Carr: I think that online education is a blessing. Sure, old fashioned art school is an amazing and life-transforming experience. But those days may be over. I’ve been hearing from many art professors who are struggling to adapt to Zoom. I’m informally teaching a painting class myself on Zoom. It can be done because it has to be done. Being on Zoom, Instagram or Facebook together with other artists is being part of an active arts community, which is what an art school should provide anyway. I don’t see how the traditional art school experience can come back. Maybe we will evolve a hybrid of traditional art school residency with online critiques and instruction, like the Low Residency MFA. It’s a response to a need. Few of us can afford the time or the expense of a traditional residential art school experience. Most of us don’t have the money or the time, or we have jobs and families. These have always been issues for artists, but they are more so now.

Can painting survive in this electronic, online environment, in which we all look at paintings indirectly, through glowing digital images? This is Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, and we might as well just get with the program. I grew up on photographic reproductions of paintings, and only saw museums occasionally. I think I and others have looked at possibly millions of reproductions of paintings; far more paintings than an artist of a previous era might have seen. I don’t know how that affected me, because we all grew up this way. Seeing a lot of paintings in museums and galleries is important. But this new world of online and digital images gives us artworks and videos of artists that we didn’t have before. And it allows us to share our work with each other. That’s a very good thing.

LG: I wonder if your spiritual outlook and long-standing involvement with Buddhist spiritual practice has played a role in your painting practice as well.

Jeffrey Carr: I have been an active meditator and spiritual practitioner in a number of traditions for over forty years. For many years, I thought of this and my painting practice as being two parallel tracks in my life. It’s only very recently that I’ve come to understand that my meditation and my painting are both spiritual practices. They are sadhanas or yogas. A sadhana is a formalized spiritual practice, often using rituals or sacred texts. The root of yoga means union, as in, union with the higher self or the divine. Both of these usages apply to painting. I could say a lot more, but that’s enough.

LG: What are some of your thoughts about why being a painter is still a good life going forward?

Jeffrey Carr: I think painting will survive for the same reason that poetry survives or music or good cooking survives; because it gives those of us fortunate enough to practice it a very deep and profound pleasure. It’s a great way to live. I’ve heard people say that pleasure is meaningless. It isn’t. Pleasure is what gives direction and purpose to our lives. The pleasure of painting can make it very good to be a human. It’s why artificial intelligence will always be unintelligent because it doesn’t have pleasure as its goal. AI can only serve the pleasures of we humans. The best thing about painting is that it is useless. It’s not necessary. Plenty of people, most people, in fact, live without painting. We could get by without it too, of course, but why would we want to?

What a wonderfully insightful interview and discussion on paintings informed by a an academic overview of a century of figurative and landscape painting. The personal insights gained by your observation and meditation practice are evident and contribute to my understanding of your amazing paintings. Thank you 😊

Thanks Eve. You must be a meditator.

Beautiful work Jeffrey Carr!! and terrific interview..

Thanks Adeline. I enjoy your Facebook posts.

Wonderful interview and I love looking at the paintings. Thank you to Jeff and Larry.

Thanks Deborah. Nice to hear from you again.

A fantastic in depth interview. I especially love the closing remarks of painting being “useless” and that is survives (as does other “worthless” pursuits of gourmet cooking, poetry etc) because of the pleasure it produces.

Thanks Kathy. I’ll look you up on Facebook. J

To this day, in late middle age and after one semester with Jeff Carr some four decades past, I continue happily living a life that he so profoundly changed (sending me to Parsons to study with Leland Bell, for one). Strange how a few words in an interview (in this case about teaching at some small art schools in Connecticut) could unravel decades in a life. In 1985 or ’86 in New Haven, Jeff taught a figure painting class one evening per week, if memory serves. We loved it and him. He swept into the room (where I briefly taught the same class many years later) with piles of books on his favorite painters to share with us. He was brilliant, energetic, and happy and like nothing our little commercial art school had ever encountered. He was kind to us, and I for one never forgot him. His casual remark during a critique one night that I was a “structural painter, like Titian,” sustains me even tonight as I prep my classroom for next semester with casts and giant reproductions of favorite painters. These include Jeff Carr, whose painting “Gauguin Still Life” sold opening night at the old Mona Berman Gallery on York in New Haven; I still have the post card of the painting, which I’ve had reproduced as a large-scale poster for teaching purposes. Highs and lows over the past forty years, like everyone, but one of the true highlights in my life was having Jeff more or less to myself for a few hours each week. And I’m just one among multitudes of his students and friends. I’m sure I speak for many when I say thank you, Jeff, for giving me so much so long after I knew you. So much, dear Jeff.

I just saw this, Jack. I remember you. Thanks for the kind comments. Glad you are well. Look at this: http://jeffreycarrart.com/exhibitions