The painter Jeane Cohen recently emailed me to tell me about her exhibitions that were then currently on display in NYC, Three Women, a three-person show at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects and Waxing Glimmer, Shedding Beams, a solo exhibition at Slag Gallery that is up through August 27 (link to a NY Times review of this show)

After looking more closely at the online images of her show’s current paintings and her earlier work from a few years ago on her website – I decided to find out more about her and to do this email interview.

I was intrigued by how she evolved from her earlier involvement with direct painting from nature to her recent abstracted landscapes. Her latest large oil paintings seem to take inspiration from the spirit of such painters as Joan Mitchell, who stated in 1958, “I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me—and remembered feelings of them, which of course become transformed. I could certainly never mirror nature. I would like more to paint what it leaves me with.” The late Thomas Nozkowski’s paintings could come to mind with his painted response to specific memories of places, things, and experiences, transforming these memories with graphic symbols, patterns, and marks into his abstract compositions.

From the gallery press release:

“Slag Gallery is pleased to present Waxing Glimmer, Shedding Beams, Jeanne Cohen’s second solo exhibition at Slag & RX gallery.

“Cohen is not only depicting imagery, but through art-making, the artist is also generating perceivable slivers of the cosmos. In the artist’s own words: “My paintings are like gentle folds in the fabric of the cosmos, which is pressed up against itself and senses itself in two places at once. Much like when I place my hand on my heart and have the simultaneous experiences of twoness and oneness, my paintings create sensory contact between minds. Each painting is like a shed skin of my consciousness.”

Jeane Cohen’s paintings reflect the boomerang-like tendencies of nature, with an internal capacity for call and response and conscious resonance.”

Jeane Cohen is an artist based in New York City and Maine, and her many notable accomplishments include A 2022 Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and a 2022-2023 Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program Award. Cohen has shown her work throughout the country and abroad with five solo and thirty-four group exhibitions. She has received numerous awards, grants, and residencies, including the William & Dorothy Yeck Young Painters Competition, the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grant, and the Ox-Bow School of Art Artists’ Residency. She received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2018.

Larry Groff: What were your early years like? Were you given a lot of support for art-making as a child?

Jeane Cohen: My family encouraged me to make art and be messy. I had a lot of alone time as a child during which I made sculptures, illustrated story books and crafted imaginary worlds. I was an obsessive maker from an early age and my hands were busy all the time. In kindergarten my teacher told me I spent too much time at the drawing table and needed to branch out into other educational activities. I have always had a strong artist drive that puts me in the studio every day. And I have been so lucky to have worked with amazing art teachers. I had my first oil painting lesson when I was 12. When I was 16 I took a more rigorous oil painting class and I basically haven’t stopped painting since then.

LG: Instead of a typical art school, you chose to get your BA in Psychoanalysis and Visual Art at Hampshire College in Amherst. What was that like for you? What can you say about how your study there has influenced your approach to your work and subject matter?

Jeane Cohen: Hampshire was great because I could think creatively across disciplines and the curriculum is focused on self-directed interdisciplinary study. You can literally study whatever you are interested in at Hampshire, and your last year is dedicated to a big project. One of my friends designed and built a car and another friend studied how zoning laws impact registered sex offenders. In my last year, I illustrated a wordless visual graphic novel integrating psychoanalytic ideas into a story about healing and community. At Hampshire, there is a strong social justice focus, so most classes you take will relate things back to ethics, sustainability, and organizing. It’s great because you learn to want to be a transformational person in the world, and it’s embedded into the curriculum.

LG: After graduating from Hampshire College, you worked as a Mental Health Counselor for a time. You then worked on various art and therapy concerns, such as many Mural Arts Projects in Philadelphia, as a Lead Therapeutic Teaching Artist, the Porch Light Wellness initiative, where you worked on a series of participatory accordion books about emotional wellness and also later worked on a Prison art project. Can you say something about what this counseling and community service experience was like for you and what, if anything, has this brought to your painting?

Jeane Cohen: That’s right! I didn’t know I was going to pursue painting professionally. I thought I was going to paint on the side and have another career. So for a while, I worked as a counselor and in community arts. During my first job out of college, I worked with adults with chronic mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and psychosis. These folks had a very different day-to-day experience of reality than I did. It suited me because I like connecting with people, and we found plenty of other things to connect about. I ran an art group for a while when I worked there, and that eventually got me going with murals and community art in Philly. But I was painting the whole time. At a certain point, I realized I wasn’t getting paid much at any of these other jobs I’d worked and I would regret not going to graduate school to learn more about painting. In some way, spending time with people and painting are like two sides of the same coin. They are both involved with communicating something meaningful.

LG: You then attended the MFA program in Painting and Drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. How was your experience there?

Jeane Cohen: I learned a lot about the tradition of image making, painting specifically, and what our eyes and minds are capable of spatially. I actually didn’t know much about art history before I got to grad school. I just knew that I needed to paint and wanted to get better. My teachers were amazing. I worked with so many people who each had a different point of view about painting, but all encouraged me to stay true to myself. SAIC is cool in that way, they get into whatever you’re into and then they show you how to do what you’re into at top notch.

LG: I’ve heard that many MFA programs today, such as at the Art Institute, can place more emphasis on the ideas behind making your art, like Critical Art Theory, and less focus on studio practice than was common in earlier times. When schools create this imbalance between talking about art and making art, it upsets some traditionally trained painters who concentrate more on visual or formal, non-verbal issues. I think it’s fair to say they get out-of-sorts when the attention is more on the wall label than on the artwork. What might be your take on this subject?

Jeane Cohen: My experience was that the curriculum was geared towards studio time and ideas were discussed in the service of making, not in the service of theory, although theory would come up in conversation. Rather than feeling a dissonance between concept and making, I realized that the two can be synonymous. Even if you aren’t a conceptual artist, your work still has concepts and ideas. It was really exciting to learn about all the underlying meanings in my work. And terrifying. Similarly to psychoanalysis, I learned that not thinking about the implications of the work actually leaves you vulnerable to ideas and biases you have never considered before.

This has stayed with me as a part of my current practice. I have always been a deep thinker, so I was very relieved to get to a place where there was a broader conversation going on about meaning. Overall at SAIC, I felt very encouraged to paint my way through obstacles in the practice and then think about the meaning of it later. And my relationship to wall text is that I am open to it, but really I’d rather just be with the art.

LG: Google led me to a portrait of you by Anne Harris, I think–on her website. Did you study with her at SAIC?

Jeane Cohen: That’s actually my drawing! I did a self-portrait as a part of her Mind’s I project in which everyone contributed a self-portrait. It’s funny you bring that up, though because at one point during the project I drew into a discarded self-portrait that Anne had done of herself, and tried to finish it for her. I think I was working on her eyes and hair. It looked liked her.

LG: Did you study with Dan Gustin? I ask this because of your focus on landscape painting.

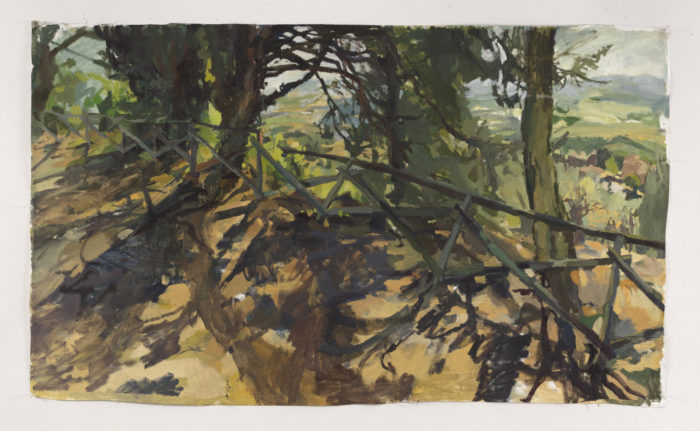

Jeane Cohen: I studied with Dan in Italy and also with Stanley Lewis, who was there at the time. That summer really got me going with landscape painting and thinking about the relationship between landscape space and cerebral-perceptual space. The first time I spoke with Dan we talked for a long time. I felt like he could see right through me. It was strange. During the course, he gave me some advice about the paintings I was making, but mostly he taught me through conversations and ideas. I gave a lecture on landscape while I was in Italy and I remember he got up and left in the middle of it because he felt like it was too performative. Looking back, he probably had a point. Dan will tell you to your face exactly what he thinks about what you are doing, which is not always comfortable but is genuine feedback.

Stanley, on the other hand, taught me how to mix a color from observation. I would paint near him, and he would come over to check what I was doing and then have me paint the whole thing over again. He’d tell me to mix the color of the sky and so I’d do it. Then he’d come back and mix it himself and show me how far off I was. This was all while he was in the middle of making his paintings of course. I guess he’d need a break and come make sure the people around him could at least mix their colors right.

LG: I understand that you were an outdoor landscape painter for a time. What led you to become more of a studio painter? How much does your prior experience with observational painting influence how you paint today?

Jeane Cohen: Yes, in graduate school, there was a period where I was painting almost exclusively outside. I was pretty much alone in thinking it was a radical idea to make observational landscape paintings. I didn’t know what I was doing but I knew what I needed to be doing. So at a certain point, I knew I needed to return to the studio and work from memory, photos and imagination. I didn’t know why, but in retrospect, I think I was learning the patterns of nature through image-making. I became more interested in the patterns of gestures and invention than trying to get the exact color of the sky I was looking at. I still rely heavily on observation as a core component of my practice. Now it’s more balanced with other things like working from the painting itself or departing from the observed reference.

LG: On your Instagram pages from some time ago, you mentioned an essay you wrote called “Art Forms of Nature: How Artists Organize Their Visual Depictions.” In this essay, you discussed “Creative Organization,” a foundational principle of visual dynamics that are often overlooked in artwork analysis. You stated, “Creative Organization is analogous to Composition, but more specifically, it conveys the particular ways that the artist’s conscious and unconscious processes present an ontological point of view through the medium of their artwork.” I’m curious to hear more about this. Is this essay available somewhere to read?

Jeane Cohen: I’ve looked at a lot of artists’ work depicting the behavior of nature, whether it is illusionistic or abstract. I started to think about the way they choose to organize their images of nature, which any landscape painter knows involves organizing an infinite range of relationships. I realized different aspects of nature are prioritized by different artists. For example, I think camouflage is a huge part of Xylor Jane’s paintings, even though she isn’t painting walking sticks. Her paintings tend to exude visceral experiences of nature, rather than illusionistic experiences of nature, as Claire Sherman’s work does, for example. I’ve written about four artists in this essay and want to extend it to include several more before I would consider publishing it. But I’m not sure if I’ll return to it. I’m not an ontological or cultural historian, so I don’t yet know how these thoughts would enter the public sphere.

LG: What contemporary artists interest or influence you the most?

Jeane Cohen: I never know what to say when folks ask me this because I really jump around with who I’m looking at. If I need to remind myself it’s OK to paint anything, I look at Albert Oehlen; If I need to feel soothed, I look at Joan Mitchell or Helen Frankenthaler. If I need an ass-kicking, I look at Katherine Bernhardt. I do look at every painter I can get my hands on, from Gregor Gleiwitz to Katherina Olschbaur.

Since I’ve been in Maine, I’ve spent a lot of time with the work of Reggie Burrows Hodges and Kathy Bradford, who both have exhibitions up now. Kathy’s paintings are good to look at for thinking about people who are constantly reinventing themselves. Her worlds are both alluring with bright colors and gestures, as well as scary, as figures are entangled and bound together, consumed by the structure of the painting itself. Reggie’s paintings are cool in that they seem to elude themselves even though the glowing marks on dark grounds are mesmerizing. The paintings are there and not there.

LG: Tell us something about how you go about making a painting. Do you have some idea about what you want the picture to be before you start, or is that something that comes from the painting process?

Jeane Cohen: I start with a color, image, feeling or genre of painting I want to make, and I build from there. My process is very experimental, and I try to be open to new ideas and turns in my trajectory as I begin the work. Sometimes my original idea lines up with the end result of the painting. Frequently I go through many ideas, often making several paintings on top of each other before I land on a good one. I stumble around a lot as I’m making, not really knowing where things are headed, or thinking I know and then realizing there is something more interesting going on in the painting that I want to work with. Most of my best paintings are made when I’m in the throes of feeling I might be onto something, yet being blind to it in the moment.

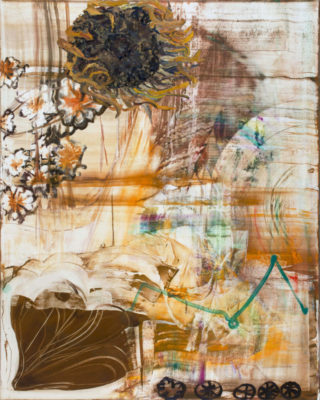

LG: From what I can see online, your more recent work, like We Were There Together and Sun Baked seems to be painted slowly and built up with layers and masking. This seems a change from your work of a couple of years ago, where the paint has more broad gestural strokes, likely painted with huge, drippy fully-loaded brushes and gives a different, perhaps more emotional feeling to the composition.

Jeane Cohen: Yes, that’s right. I’ve been deep into making a bunch of slower paintings in the last six months. I’m not sure I’ll continue with this way of making in my practice, but it has been useful to see what this process can bring. I started with the slow paintings because I needed a break from making fast paintings, which I had done pretty much non-stop for the past couple years. In 2020 and 2021 I made over two hundred paintings at a quick pace, so I needed to slow things down. Slow is not my natural way to paint, but I also like throwing a wrench into my process to see what happens. Painting slowly lent itself to weaving paintings together and staring at them for a long time before making a move. It has allowed me to prioritize seeing in the work rather than leaving everything to my hand. Now that I have a stronger eye for my work, I can bring that back to the other paintings.

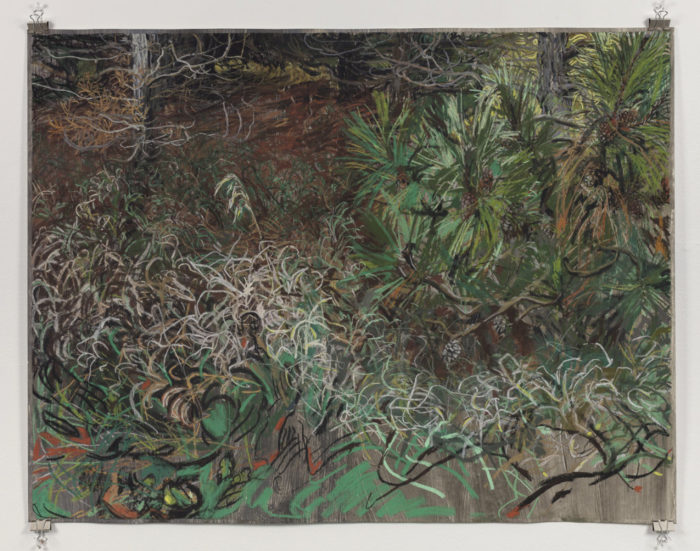

LG: What can you say about how your painting process has changed in the past few years?

Jeane Cohen: I have welcomed more imagery and collaged elements into the paintings. I keep adding new themes like animals or fire. They arise in the work on their own for the most part and I try to get out of the way and make room for these shifts to happen. It’s important to say that the arrival of these elements in the paintings isn’t about owls or horses. I mean in a way it is because that’s the subject, but for me the subjects are placeholders for emotional experiences and different kinds of awareness.

LG: There seems to be a lot of recurring imagery in your work. You often include animals and birds, ornamental garden gates, stars, sun, fires, forests and more. Where do these come from, and why might they be important for you?

Jeane Cohen: I love the rhythms of nature, like the moon and the tides. I like that nature is transformation and life and death all at once. In art people have words like cliche or classic for artists who embrace nature. I prefer the word tradition, and I accept the tradition of nature, even though I don’t always like it. But I am indebted to it, and I want to understand it better, so I pay homage to nature through painting forest fires and celestial skies sprinkled with animals. The ornamental garden gates are very fresh for me. They probably point toward my interest in the peripheries of nature. Of course, it’s all nature in the end, but there’s something to be said for that liminal space at the edge of nature. What is that space like and is it similar to the space at the edge of a painting? It’s like asking the question, what is at the edge of the universe?

LG: I particularly enjoyed your 2022 oil painting diptych, Night Fisher . It reminds me of some of the more enigmatic, mysterious later watercolors by Charles Burchfield. This painting seems to simultaneously depict a forest, a field of sunflowers, a seascape and perhaps flying fish . Please tell us something about why and how this painting was made.

Jeane Cohen: Charles Burchfield is an interesting point of reference. There’s a dappled positive-negative pulsing going on in the painting that’s similar to Burchfield’s work. Where I may depart from Birchfield in a major way is through collage and hurling different events and spatial orientations into the painting all at once, while still retaining some form of associative narrative, which in this case, is where the title comes in. Like Burchfield is interested in stretching one point of view as far as he can, and I am interested in making many points of view relate. And the paintings are held together by several synonymous overlapping landscape events. I haven’t figured out what keeps me in the genre of landscape, but my best guess for why landscape arises in the work time and again is that it helps with orientation. I’m painting otherworldliness but I’m also still painting a world. I’m keeping it tied to human experience and I think it’s relatable in that way.

LG: Do you listen to music while you paint? If so, is there particular music that works best for you?

Jeane Cohen: I have great admiration for musicians and sound because it is our primordial art form, which precedes the visual and movement-based arts. It is so fundamental and automatic, listening can help free me up to take risks in painting. There’s not a particular genre that works best, I like it all. I just need to work from something that sounds fresh, and not the same old watered-down stuff, unless it’s a really good pop song, which is great for big painting moves. But yah, hip-hop, classical, folk, indie, jazz etc. Actually lately I’ve been trying not to listen to music while I work so I can concentrate entirely on the paintings. After a ten-day meditation retreat this winter I came back to the studio and realized how distracting noise is to my practice.

LG: Speaking of music, I see where you recently contributed album artwork for the record, The Uproar in Bursts of Sound and Silence , which you said was also called Bird Songs for The Stars.

Jeane Cohen: Yes, I got to contribute the artwork for this amazing album! My friend, Evan Strauss, was working on this project for a long time and asked me if I would like to make something for it. He’s a bit of a mystic and the original title was Bird Songs for The Stars , so I made a cover to fit that theme of a bird grazing the surface of the water and the stars reflecting from the night sky. Actually, it’s funny because that painting is also called Night Fisher . It was the original Night Fisher and now there is a second Night Fisher painting. This happens a lot in my practice. I end up having to retroactively title things I and II and so on.

LG: I understand you currently live in Maine – but you just recently won a 2022 Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program award where you get a year-long, rent-free studio in DUMBO, Brooklyn, NY, where 17 artists were chosen out of 1500 applicants. Congratulations! That must be huge for you. What thoughts might you share about this new move?

Jeane Cohen: I feel very fortunate to have been awarded this residency and grateful for the opportunity to return to New York City, where I had been living in 2019. During Covid I returned to Mid-Coast Maine, where my family is from. Maine is so vast and filled with abundant nature that it’s both comforting to feel so held and intimidating to feel so small. The wind and the sea and the forest are fine with or without me, and so it has been really good for my artist practice because it’s been just for me. It’s kept me clear-headed about the work I make. But I really miss the intensity and passion of city life, and I’ve probably been a bit too isolated in Maine, so this opportunity has come along at a good point for me.

LG: You had a couple of solo exhibitions in 2019, titled Orgonon I and Orgonon II, at the Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, and the Miami University, Oxford, OH. I’m guessing your show’s title referred to Wilhelm Reich’s property in Maine called Orgonon, where he had worked on his Orgone Energy Observatory and related in the late 40s. What can you tell us about this exhibit?

Jeane Cohen: I didn’t know about this property in Maine! I named the shows after a slightly different spelling, Organon, which was a word I stumbled upon in the dictionary when I was trying to name my shows . I was searching for a title that would convey my interest in nature, diversification, and ideas, so I went to the library where they have a multi-volume set of the Oxford English Dictionary. Organon was close to ‘organic’ and ‘organ’ on the page. It is defined as a system of thought, organ, or instrument, so it was a good fit. A lot of my work is about the nature of thought, and each work in the show was a different instrument of thought.

LG: Sorry, I spaced on the spelling difference – it just seemed to fit with your subject matter and your past study of creative uses of psycho-analytic ideas at Hamshire College.

LG: What advice might you offer aspiring young painters who hope to get recognition, advance their careers and show their work in better venues?

Jeane Cohen: Nothing revelatory. I think it’s all in the service of the work. That has to come first, and everything else needs to be to support the work. Otherwise, you are doing everything for the wrong reasons. Once you come to terms with your unrelenting need to make art or whatever it is you do, then you can focus on making that obsession come to life and then later start to think about venues and recognition. The thing is, in order to get the recognition you have to keep putting yourself out there hundreds and thousands of times before someone might take notice. And you have to keep in mind that success doesn’t necessarily correlate to good art. You can have success without good art, and you can have good art without success. As long as you understand this, you are being honest with yourself and staying aligned with what you have set out to do in the first place, which is to make the work.

Larry, thank you for this interview. It’s nice to have an opportunity to reflect on and speak in-depth about my life and practice.

LG: The pleasure is all mine, thank you for your time and consideration in writing your thoughtful answers.

Leave a Reply