I was fortunate to become friends with Jean Sbarra Jones during the time we studied painting with John Moore at Boston University’s Graduate School back in the early 1990’s. We kept in touch off and on over the years and I’ve long been impressed with her painterly vision and inventive ways of transforming imagery, often photo-based, into visually-compelling compositions that also hints at a deeper meaning. I was excited to see the recent work that she posted on Facebook and her show this past winter at the Alpha Gallery in Boston. I was very pleased that she agreed to an interview with me on Skype.

Jean Sbarra Jones has an MFA in painting from Boston University College of Art. She has exhibited widely, received grants for residencies, and been published most recently in Poets/Artists magazine, AcrylicWorks5 and Studio Visit Magazine. Her work has been shown recently at the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art and RJD Gallery in Bridgehampton, NY. Among her collectors is the late Kenneth Noland, a well-known 1960’s color field painter. Jean currently has a solo exhibition at Alpha Gallery in Boston.

This past December she recently had her first solo exhibition with Alpha Gallery in Boston, Ma.

Larry: I recall you saying that success in painting can require the same level of drive and devotion that a professional musician needs to have. Some students and painters today take painting more casually. Could you speak more about your thoughts on this?

Jean: I agree that there does not seem to be the same level passion and sacrifice that goes into being a fine artist. I think this may be because there’s no discernible reward. It currently is very difficult. More than it was when we were out of graduate school. Galleries are closing and there is more supply than demand. Social media’s ability for instant gratification has interrupted the ability to focus. Everything is just so fast. It’s a completely different world and there are very few people that would really want to take the time to develop as a painter and in some way, I can’t blame them. You need to live pretty simply and say no to a lot of things. You have to want it more than you want just about anything else and that’s not happening for most people. Even if you do want it and put the time and devotion into your work, it doesn’t guarantee anything. The people that are financially successful in art aren’t necessarily really doing the art that they want. I think that fame and money are not the end goal for serious artists.

What we really want is financial freedom to allow more time to do what we do. You don’t need a lot if you’re really involved in your work and I think that’s true for most artists, writers, actors, musicians etc. If you’re really doing the work that you want to do you just need time to do it and that’s where success for me starts to happen. Being successful is being able to stay in it. I’m really happy that I’ve maintained my practice. I don’t know anyone personally that’s making a living solely on painting sales right now, usually if they have all the time in the world to paint, they have another source of income. I think with social media being what it is, an artist can sell well on their own if they put the time into learning how to market. That is a whole other issue that comes with some compromise and savvy. I am fortunate in that I love teaching, being able to give some of what’s been given to me and to see exciting young artists grow.

Larry: Very well said and couldn’t agree more. Success also means being able to do what you love, excited to get up each day and get to go make art. Being a successful artist means being happy and engaged with your art and life; getting to have a great life is the best reward.

Jean: Especially now, with all the crazy things going on with the pandemic. In the very beginning of the pandemic, I was just numb with worry and grief; mostly grief. I was in the middle of a semester teaching at Mass Art and everything went online. It was a huge learning curve, stressful and chaotic. Eventually, it became manageable. My practice suffered. I kept hearing about artists painting every day, cooking, gardening and cleaning out closets. This made me feel horribly inadequate. But I was grieving. I took the time to feel the heartbreaking reality of all the loss. And it was immense, still is. I am slowly learning to accept the uncertainty of the present. I suppose as artists our life choices make us more able to hold some of the doubt and pain of the present, and to move through it, use it. On my better days, I can do this. With art, there is an inherent hope that the painting can get better, that you can grow, change and become something more than when you started. That is hopeful, I hope.

Larry: We knew each other during our time in graduate school studying under John Moore at Boston University but I don’t know much about your life before then. Can you tell us something about how you became an artist?

Jean: Before deciding to pursue art, I wanted to be an actress. That didn’t work out for a number of reasons, mainly lack of confidence. I ended up going to UMass Amherst for college and became an art major. It was not a great experience. The department was mostly conceptual. For my BFA thesis I did a bad piece about a burlesque performer with broken mirrors and ripped fabric. My painting class involved painting on the floor with magic markers and primary color acrylic paints. The professor would arrive halfway through the class and give brief and positive reviews of just about everything. I graduated, stayed in Amherst area for a while and then moved back to Boston. I was pretty discouraged because I realized I didn’t know how to draw or paint. I moved back to Boston and I started taking classes at the Art Institute of Boston. I studied painting with Geoffrey Rogers who was a British modernist painter. I did this before I knew much about drawing. I started painting somewhat abstractly with a limited palette of greys. I began with all white still-lifes in an impressionist manner, moved on to study Cubist form and then Fauvist color. I went from conceptual art at Mass Art to modernist abstraction at the Art Institute of Boston. I also studied with Bill Holst, who had studied with Hans Hoffman. I am grateful to have gotten some experience with an abstract language and color theory. My next step was a perceptual life- painting class where I mixed and applied colors that I saw. Observational painting for me was always a combination of what I perceived and what I had learned about color in an abstract sense. I pushed color in different directions. I then went on to BU as a special student for a couple years to learn how to draw in their undergraduate program.

Larry: I didn’t know that you studied in the undergraduate program at BU.

Jean: I didn’t actually graduate from BU’s undergraduate program. I was taking some classes and sitting in on others. I learned in a way that was the opposite of linear, sort of backwards. I kept trying to make up for what I felt was missing in my education. But after a while, everything kind of came together. First conceptual, then abstraction and then finally classical. When I got to graduate school, I felt equipped. I was pretty confident in graduate school of being able to understand the language being used by someone like John Walker. The ideas that I developed as an undergrad kind of lead into some of the stuff I was painting. It was a nonlinear path in terms of education. In the midst of all of that was a lot of craziness in my life; lots of moving around and different jobs, mostly waitressing. I was in the restaurant business forever and that’s how I supported myself.

Larry: How much did your study with John Moore have an effect on your work?

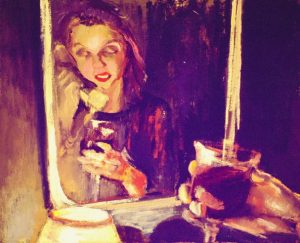

Jean: It had a great effect. I remember he had gone to France for the first time during my semester with him. He was inspired while looking at French painting and came back with new ideas about color. I was very adamant about not using photos and working only from life in natural light. I would create involved setups with costumed figures in interiors. What I was doing from life was veering more towards expressionism than realism. One night, a fellow student was in my studio drinking wine and I started to take snapshots of her. One was of her talking on the telephone and looking in the mirror. I did a painting from that snapshot that took about half an hour. Later on, John Moore came into my studio and I was showing him large paintings done form life. He saw one of my friend from the photo in the corner and said “that’s your best painting”.

He loved what I considered my throwaway paintings. I then started to stage and paint similar narrative situations which is what I showed at our graduate thesis exhibition. I was working from life and hiring models while simultaneously painting from staged photographs.

John Walker was really interesting. He responded to my work in a more formal way. We talked mostly about color relationships. My experience studying with a British painter previously had influenced my use of warm and cool greys. John Walker was also British and this resonated with him and gave us a connection. He never talked much about content. John Moore was absolutely pushing me into narrative content. He wanted to know all about story, the what and why I painted. Studying with these two together, worked out well for me. I only had one semester with John Walker. Graduate school was a great experience.

Larry: What was your life like after graduating and how well did graduate school prepare you for life in the real world?

Jean: I think it prepared me really well. Back then things were so different. Right after getting out of graduate school and I started to get into a lot of different juried shows with well-known jurors which was very encouraging. One thing that was really exciting was I got into a show at the Cheekwood Museum of Art in Cheekwood, Tennessee. One of the jurors was Kenneth Noland and he bought one of my paintings. He awarded me second place in painting, and he bought my painting for his wife who, at the time was the editor of Architectural Digest.

Larry: Do you remember what the painting was?

Jean: It was called “What are you Wearing?”. It was in my graduate show and the funny thing is that he is an abstract color field painter. He’s not a representational painter. I think that shows how much abstract language I was using in a lot of my work. I was waitressing and entering into all of these juried shows. I got into a gallery in East Boston. I had two shows there and I was selling work. The gallery ended up closing. After that, I got involved in things like the annual AIDS auction in Boston and open studios in the south end, where friends of mine had studios. I started to have studio parties at my house and people were buying paintings. I had a lot of friends and friends of friends came to these parties. I was much more social at that time. I made some money, not a ton but maybe six or seven thousand dollars in a weekend.

I noticed that when I put paintings in the AIDS auction people were seriously bidding. The evening of the auction, someone from Clark Gallery in Lincoln noticed this and came over to me asking if I had more work to show. I did. I brought a piece to their gallery. They wanted me to sell my work for way more than I was charging. At the time, I thought that if I continued with them, I would have to change the prices that were working for me in my studio sales. I had no guarantee that that was going to be a good move for me. I remember selling a painting through Clark for about $900 for an 36 by 24 inch oil painting. The gallery was horrified that I charged so little because they ended up not making much money.

They were not interested in my work at my prices. I don’t think I even wanted gallery representation at that point, I don’t know and still do not know if it was a good idea or not, but at that time, other things in my life were kind of a mess.

I continued to waitress and paint. I wasn’t making a ton of money, but sales were somewhat consistent. I landed a job teaching at the Art Institute of Boston, by complete surprise. A week before classes began an old friend of mine from a previous graduate class at BU recommended me for a position that had been suddenly vacated. I was scheduled to teach the following Monday. Having never taught before with the exception of being a TA in graduate school, I was terrified. I was handed a daunting syllabus that I did not understand from a very seasoned drawing teacher named John Lanza. I ended up going to this man’s class every week and following exactly the lesson that he was teaching. To this day, I still teach much of what I learned from him. It was really clear and highly effective. I think that my experience as an undergraduate was so maddeningly haphazard that I became almost dogmatically structured and determined to give my students something concrete. It was a sin that I did not know how to draw a box in perspective with a BFA in art. I eventually had to stop waitressing.

I’ve never stopped adjunct teaching. I have taught all kinds of classes at four different colleges in and around Boston. I currently teach two classes a semester at Mass Art .

Larry: I remember the harbor paintings you were making years ago from when you lived in Gloucester, Ma. Were those from life? I’m curious about what you can say about that earlier work and how your work may have developed along any chronological path?

Jean: The Gloucester harbor paintings were from photos. I have painted and taught landscape plein air for decades. If I hadn’t had that much experience from life, I never could have painted well with the photo. Understanding what actually happens in life and how value works is essential because often color and value is really different in a photo. It came to a point that while outside, I was not as interested in exactly what I was seeing but how I could make what I was seeing transform into something more. I discovered that my main interest was light, particularly fleeting light that would disappear soon after it appeared, thus making it almost impossible to paint outside. Therefore, I didn’t. I broke the rules I had been taught that the only viable way to paint landscape was being in front of the subject. Instead I chased light like a photographer.

The Gloucester harbor paintings happened after I got married later in life. My husband loves to fish, and he had a boat. I loved seeing all those rusty fishing boats so I took a bunch of pictures. I reduced my palette to warm and cool shades of grey. I wanted to capture the particular grittiness, strength and abstracted forms of the working harbors without the distraction of more descriptive color.

Let me give you a summary of my painting chronology here.

After graduate school, I continued doing narrative paintings of women in hotel rooms. After a while, I discontinued that series and started painted still-lifes of dresses because I couldn’t afford models anymore. I eventually brought the dresses out into the landscape, mostly hanging from trees. After marrying a man living in Gloucester, I did a series of monochromatic paintings of fishing boats. I felt like the work wasn’t personal enough. I brought back the dress. I took it out and onto the docks of Gloucester and painted more monochromatic paintings of the dress in the wind. They had to be from photos because there was no way that they would have lasted for any length of time in the light and weather. That group of paintings was exhibited at the Attleboro Museum in a show called “Eight Visions”. I also showed this group of paintings in collaboration with a theater professor at Gordon College where I was teaching at the time. He instructed students to create stories about each piece. They would also narrate them as theatrical monologues. In the gallery, while looking at the paintings, the viewer could pick up a phone and listen to one of these monologues. They were about different things; like a woman who left her wedding dress on the dock or an old man missing his long-lost wife.

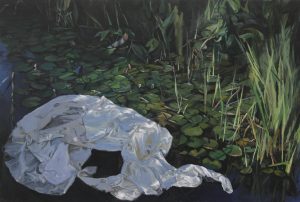

The next series of paintings were created after I went out on a boat with my husband. I was trying to try to find a way to get the dresses on the boats. I was tossing them around, hoping one would land on a rusty old boat, and while doing so, one of them ended up in the water. It fell and sunk. We lost that dress, but I took a picture before it disappeared. I loved the image of light falling on fabric and water, wet and dry. I started staging more situations with the dress in water. The photograph is integral to the process of staging the dress. My husband ties clear fishing line to the top of the dress and then tosses it into the water until I am satisfied with the relationship of dress, water and landscape. Often, it just looks like a blob and needs to me moved. I paint the image initially, very loosely from the reference photo. I start painting the chosen image with broad shapes of warm and cool grey. The dress eventually appears, and color is gradually intensified. The result is intentionally theatrical.

I am always looking for different places to bring the dress. On a tenth wedding anniversary trip, I brought the dress to Aruba and staged it under mangrove trees. I wanted locations that would be evocative and visually stunning. I am like a director of the dresses. They became actors in my scenes. My husband is an actor and director as well as being a theater professor. He teaches in the Theater Department at Gordon College. We travel to London and Edinburgh every summer and see about 20 productions in the course of two weeks. Theatrical lighting and design have been a big influence for me. It came full circle because I wanted to be an actress when I was younger.

Larry: Are there other autobiographical aspects to your paintings?

Jean: Yes. I see the dress as a metaphor for many aspects of myself. When I was doing the paintings of the women in the hotel rooms, they were a sort of a mirror of what was going on in my life. And then I had this kind of spiritual awakening which changed the course and circumstances of a fairly destructive lifestyle. I dropped the subject of all the women in the hotel rooms because I wasn’t really connecting to them anymore. I started to paint the dresses all white as I went through a purification of sorts. When the dresses ended up in the water; it was back to color. I started painting the same vintage dresses, but the narrative is less specific and more universal. The paintings are also metaphors of a difficult life. The water is renewal. I feel like my life is great right now. I really like where I’m at and what I’ve been able to do. I didn’t always feel this way. The dress represents both the dark the light. Some of them feel darker than others. It is usually connected to what’s going on in my life at the time. With the narrative, I hope people will bring their own stories to the paintings. I am much more interested in creating mystery. I like when things are less literal, more emotional without being sentimental.

Larry: What can you say about the relation of the landscape to your dresses? Anything important about how they evolve in terms of how much of the landscape and surroundings are visible along with the dress?

Jean: The dresses often have elements of the landscape in them. I have always been drawn to landscape, especially the light that happens outdoors in early morning and late afternoon. I started painting landscape recently, as a way of having a different rhythm in the studio. The dress paintings were labor intensive and emotionally weighty. I needed a break. Landscape started out as a way to paint faster and more expressively. Gradually, they developed into a serious body of work that I was invested in.

I want the landscapes to have the same kind of mystery, drama and light as the dresses in water. There is a connection between the two; hopefully you can see that. It’s the Hudson River school mixed with Max Beckmann.

Larry: The show that you just had at the Alpha Gallery in Boston was mainly landscapes or were there dress paintings as well?

Jean: No, there was only landscapes in that show.

Jean: I had a solo show in Seattle last summer at Suzanne Zahr. I was invited this summer to be included in a show at Beacon Galley exhibition, Mixed Messages From the press release: “Mixed Messages is a group show bringing together multiple artists and their work around the concept of sexual violence. Our intention is for visitors to get a sense of the pervasive and insidious nature of sexual violence in our culture.”

This is what the director Chrisine O’Donell says about the dress series:

“The Dress in Water series by Jones is a series of evocative acrylic paintings showing dresses floating or discarded in bodies of water. With their ability to be interpreted by the viewer as either haunting or cathartic, these pieces represent an opportunity to consider the stories within the paintings as well as one’s own personal story.”

Larry: I’d like to ask you about your process, especially with regard to drawing. Do you have a regular practice of drawing independent of painting? What is the relation of drawing to your paintings? Do you work everything out in the drawing first or just jump in and figure it all out in the paint?

Jean: I draw a great deal with my classes, I teach Drawing One. I am very grateful about that because my eye to hand activity is always in motion. When I paint, I don’t do a drawing beforehand, I actually draw with the paint. I gesturally draw and paint from large shapes to smaller ones. It is an extended gesture painting. I’ve always worked with everything going at once. It is like a blurry photo coming into focus.

When I draw it is a separate thing. I draw mainly with white chalk on black or toned paper. Drawing is always connected more to value than line. I see with light. Line drawing didn’t come easily to me, but value did. My charcoal drawings were way ahead of my linear drawings. I pushed myself to learn how to draw better and as a result I teach drawing in a really structured way. It was hard-won for me. Nobody ever taught it to me well enough. I’m angry about that and I want to make sure that my students get a good foundation in drawing. I constantly draw and measure while I’m painting

Larry: What other influences are important to you with this work?

Jean: Surprisingly to me, Frederic Edwin Church. I remember John Moore showing me his paintings years ago and I hated Church. Thinking, why are you showing me him? And it’s so funny that I’m actually painting these kinds of romantic scenes. There’s this feeling of that whole period of Romanticism. I never really looked at anything like that.

Jean: For my landscapes I look at Munch, Cézanne, Matisse, Hudson River school painters, Corot among many others. One of my favorites is Turner. For my Dress paintings, I would say John Singer Sargent is my biggest influence. All of the Ashcan school painters, particularly, George Bellows are also in the mix of highly influential.

I am aiming for an illusionistic space, I’m not as interested in flattening the space, although that sometimes happens. I am looking for a way to walk into the painting instead of being on the picture plane like a cubist work. The training that I had in abstraction really has come into play in all my work which I’m grateful for.

Good interview, very grounded in practical reality. Great work; would love to see more of those landscapes.

Wow. Just amazing. I could not believe that is painting. Really nice.

what are these sketches i really like these man, painting is a very creative work now everyone can do it but here it is so perfectly

I wondered if Jean might want to know about an informational website I’ve made dedicated to her former teacher, William H. Holst (student of Hans Hofmann).