I’ve long marveled over the diminutive works of the Canadian painter Harry Stooshinoff and have been impressed and inspired by his success and creativity with selling his works online, no mean feat in this day and age. I’m pleased to share this interview where he talks at length about his background, process and thoughts on making paintings and would like to thank him for his generosity in responding to my email interview questions. I thought his website’s statement is a great introduction for those who may not be familiar with him and include it here:

I am both a painter and teacher. I hold a B Ed, BFA and an MFA. I have been producing artwork almost on a daily basis for over 35 years. A few decades ago I started making small pictures so that I could start and finish the piece in one sitting. The work is small because an intimate scale encourages maximum intuition, freedom, and experimentation.

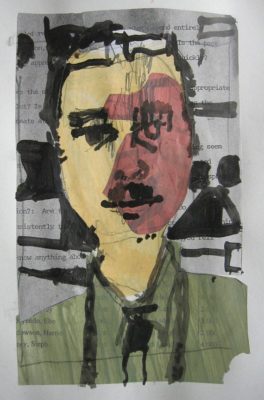

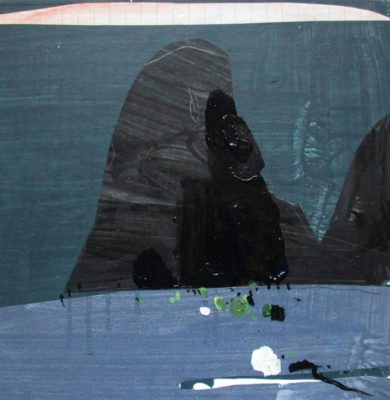

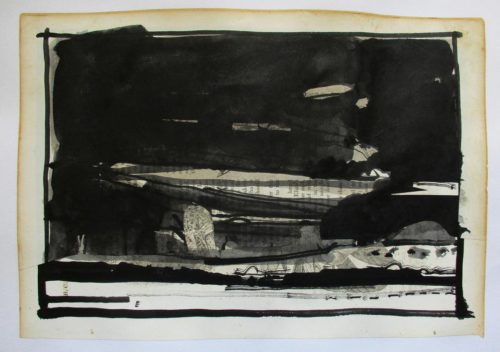

My work is both abstract and figurative, and there is no inherent contradiction between these sensibilities; one inclination supports the other.

I am prolific and I do not wish to die with 10,000 paintings under my bed! Making small work also solved a few practical problems; small work is easy to mail. I very much enjoy selling art online. Mailing pieces to destinations all over the world is a great pleasure.

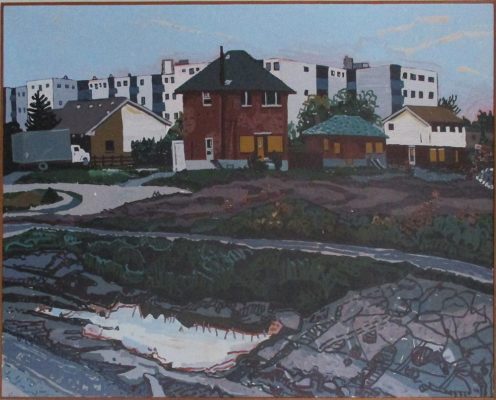

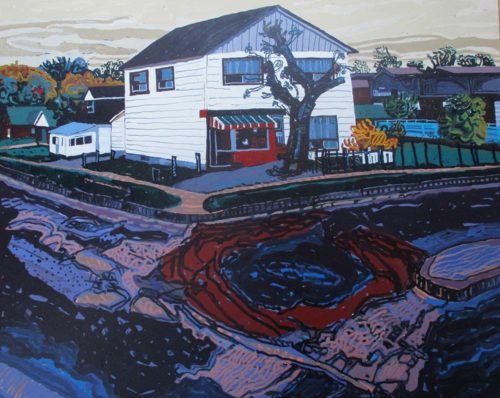

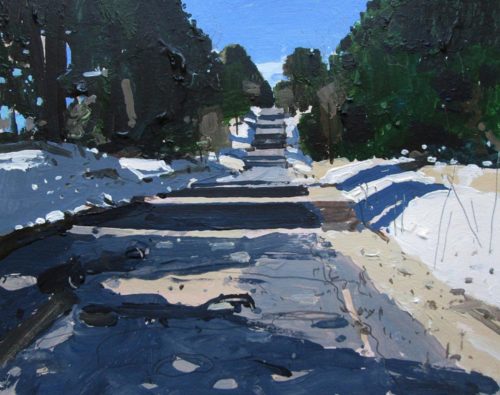

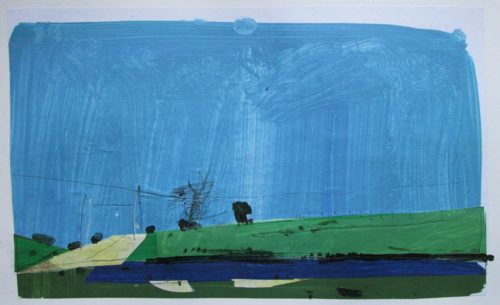

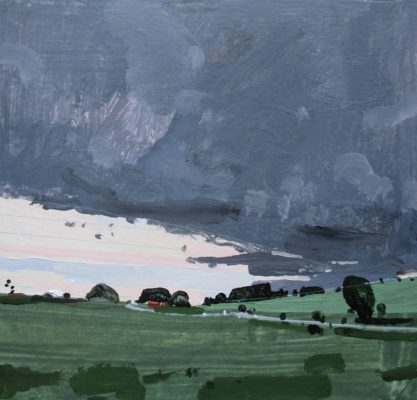

I live in the rolling countryside of the Oak Ridges Moraine, an ancient landform located just north of Lake Ontario, and am inspired by what I see every day. I roam this unique place in all seasons, and document my impressions. At first view, rural environments may seem natural, but they have been continually altered and reshaped by man. The landscape will be very different tomorrow; it seems negligent not to record how it looked and felt today.

It’s a big NOISY world, so I make small, quiet paintings.

Larry Groff: How did you decide to become a painter?

Harry Stooshinoff: I remember wanting to be an artist in Grade 7 and searching out all kinds of books and materials to learn techniques. I always did very well in school so I was no stranger to a library. In high school, art was not offered, and this may have been a great thing in the long run. Through those years I learned on my own by emulating examples from art history, and that method would prove very useful later on. I was producing artwork on a regular basis all though high school and by that time I knew that I would study art in university. I think from a fairly early age I was seeing that through painting…there was this possibility of enchantment, of being carried into another place.

LG: What was art school like for you in Canada when you studied there. Where there many people doing landscape then? How did you get to be a landscape painter?

HS: I did my BFA in studio art at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. When I arrived I fully understood that I knew next to nothing and was very ready to learn. I was an academic high achiever in high school and a certain kind of humility comes with that. You expect that things will not be easy, and you expect to work hard for everything. The program at that point was Open Studio and was based largely on studio critiques of work produced through the week. Looking back on this experience now, I think this program worked well for me. I was terrified by my own ignorance so I produced a great deal of work. One important method was based on going to the library, deconstructing artists from my favourite movements, and allowing them to influence my painting and drawing development over a period of time.

The faculty was mostly post abstract expressionist in their outlook, with critics such as Clement Greenberg enjoying huge popularity. The abstract painter Otto Rogers was the head of the department at this time, as was Stan Day (1974-79). There was a period of time when I painted urban landscapes of Saskatoon in a Fauve manner influenced largely by Derain and Dufy. The department did have a landscape painter on staff (Wynona Mulcaster) in earlier years, and her influence was still felt, but one sensed, and this was reinforced in many ways, that the abstract concerns of a painting were always primary. For those who took the teachings to heart, the process was analytical and rigorous. I remember showing up for term-end evaluations with a stack of works on paper 2 feet high. Figure drawing, ceramic sculpture, printmaking, drawing, painting and art history were all essential parts of my studies there. At the end of my 3rd year I also did a summer session at the renowned Emma Lake workshops in northern Saskatchewan. This was an important time because one had a chance to work next to world-class artists from Canada, the US, and Britain for a number of weeks. Anthony Caro was making sculpture in the parking lot. I still remember admiring how Otto Rogers moved layers of wonderful greys as I watched him work on a works on paper series. I also met my wife, painter Jane Zednik in my 4th year, who was at that time doing her MFA in painting at the university. She was a large influence in my work over the next number of years, and through graduate school, when I worked in a more narrative and figurative manner. After completing the BFA, I studied at a year-long painting workshop (run by Canadian painter Takao Tanabe) at the Banff Center. This was also incredibly helpful since influential artists were brought in for talks and individual critiques every 2 weeks. A great range of opinion, perspective, and guidance could be had in a short time. I still have very fond memories of a summer printmaking workshop taught by Jack Lemon, creator of Landfall Press.

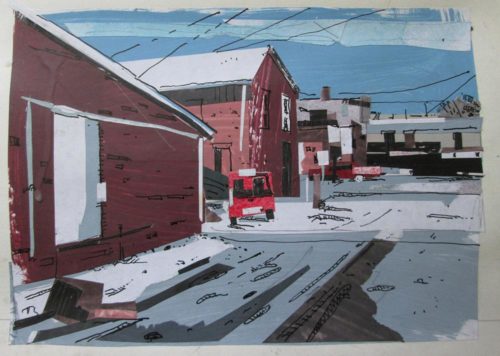

I then completed an MFA in painting at the University of Calgary, but my work at this stage was still dealing with a variety of narrative themes. I vividly recall one experience close to the end of my time in Calgary. I took all of my paints and a heavy, cumbersome drawing board to a bit of turf next to a busy street beside the campus, and painted a 22 x 30 inch landscape while sitting on the grass. In retrospect it was in important cross-over piece…..I always remembered this piece of work. Pure landscape did not make a full appearance in my work until a few years later when my wife and I moved to Oshawa, Ontario in 1983. I found the industrial city ugly and inhospitable, and the only way I could figure out how to make peace with it was to walk its streets for countless hours, taking photographs that I would later paint from during the nights. A series of many 22” x 30” paper pieces and 4 x 5 foot canvases of urban landscape paintings resulted.

LG: Have the great Canadian modern landscape painters like Tom Thomson or the group of seven and similar been influential to you? Any other painters work been important to help you find your own voice?

HS: Over more than 4 decades of painting, many artists have been an influence, at different times. In the very early teenage years I would gobble up all the history of art I could get my hands on. But in small Canadian prairie towns, art wasn’t a large concern, and there certainly weren’t galleries to visit. The wonderful old town librarian would use inter library loans to order books on artists I selected. I recall giving a lot of careful attention to Constable as well as Baroque Dutch landscape painting. I looked carefully at the Group of 7 mostly through reproductions. But there was one year when an excellent selection of their landscape paintings toured through small Canadian western towns. In my town, Kamsack, they were hung in the auditorium of the junior high school for a weekend. I loved that and it was the first time I saw important paintings close up. And it was also the first time I saw Canada represented in paintings. But even then, one doesn’t see the Canadian prairies represented in works by the Group of 7, so there was still a sense that art was made “somewhere else”. I loved David Milne in the early years and still appreciate the work today. I first encountered his pieces at the Mendal Gallery in Saskatoon, when I went away to university, for my BFA undergraduate degree. J.W. Morrice is also a Canadian landscape artist who I admired, especially the small on-the-spot pieces.

Through the university years I took apart every artist who appealed to me. The fauves, the French impressionists, most of the German expressionists, French expressionists like Soutine and Georges Rouault, and select abstract expressionists like Robert Motherwell and Arshile Gorky were all influences at certain times. There was a time when I painted personal narratives, dream images, and book illustrations–medieval manuscript illuminations were one of the influences for that body of work. My MFA degree thesis at the University of Calgary was titled New Humanistic Pictorial Art, with artists such as Saul Steinberg, Robert Crumb, and Jean-Michel Folon, cited as influences. The main idea argued was that there needed to be more than purely formal, plastic, and painterly concerns driving the work. Societal or human situational concerns needed to be somehow addressed. I painted purely abstractly only for a short period of time; through all my investigations, I wanted to paint the world, but this needed to be done in a modern, authoritative way. Picasso and Matisse were important to me almost right from the start, and they remain very much so today–likewise Joan Miro. Really, through all this time I have been very much concerned with method as much as subject, so my range of influences has been fairly broad. The list could go on for a very long time. I still spend a lot of time looking at paintings and drawings every day…all of that has an influence.

LG: Was there any particular lesson or experience you had that helped you become the painter you are today?

HS: Looking back now, very early experiences seem important. My first years growing up on a farm in eastern Saskatchewan were happy and idyllic. I remember being 6 years old, climbing tall aspen trees, and listening for a long time to the sound of the leaves in the wind, and enjoying the way the tree moved with the wind. I ran freely all over the farm and it seemed an enchanted life. I idolized an older brother who later died at 21 in a car accident. He was great at art and I would carefully watch all the things he did. I recall waking up, in that groggy state between dreaming and waking, and seeing a combine harvester my brother made out of plasticine, sitting on the window sill in front of me. It seemed a thing of magic and I remember holding on to that semi-awake state just so I could prolong the wonderful feeling of staring at that sculpture. We also had a person who lived on the farm with us. I called him grandfather but he was an old Russian craftsman and carpenter who helped on the farm. He built his own little house there, and he decorated various outbuildings with crafted tin work. For me he made a wonderful carved wooden rocking horse, with hand-wrought stirrups and metal moving fixtures, a real horse hair mane and tail, and a hand-tooled saddle. It had marble glass eyes and was beautifully but primitively painted. He also made toys for my brothers and me. Most of the furniture in the house was handmade by him and brightly painted. This type of Doukhobor furniture is very collectible these days. For the first 7 years of my life we lived on this farm with no electricity, no running water, but they were happy years where I learned to love solitude, and where I saw that people could make a bit of magic with their own hands.

Not all early years were as happy. An alcoholic father could not keep the farm afloat and squandered a great deal of the money from the sale of the land. My 12th year was painfully memorable; the family, while awaiting the closing date on a house purchase, was for a few months that seemed like an eternity, squatting in the house of an alcoholic lady with our furniture crammed everywhere including the front yard. Living in a house with daily binge drinkers was unbearable. I remember the great relief of finding a sleeping place under a table with other furniture jammed up against it, which at least gave some semblance of privacy and ‘place’. In all years hence, the security of ‘home’ has been the greatest value, and it’s ‘home’ that I paint today and every day. The idea of being able to depict and comment on all aspect of one’s life seemed to my very young mind as something that could save me, or at least prevent me from disappearing. And a few years later, when the home situation stabilized to a tolerable degree, the study of art history showed that all manner of pain was on display in the range of masterworks. All of my early years were documented in narrative drawings and paintings made between the ages of 22 and 24. Later on, in graduate school, when the work of many outsider artists became a useful influence, I remember the joy of finding the work of the Polish, and sometimes homeless artist Nikifor; he could do so much with almost nothing. I loved the work but was also inspired by his life and thought “well, if it all goes completely to hell, I could still live like Nikifor”.

LG: What are some of your most important concerns when first starting a painting?

HS: I always want to know that this next painting is not like the one before, or at least there has to be some sense of departure. There has to be something new in both the process and intent. Without this, I lose interest. And there has to be a glimmer, some chance that I might be able to create some sense of life through this work. I also need to know that I’m ready to paint…which means that my mind needs to be empty, and my body relatively loose and relaxed, ready to move and react easily and happily for up to 2 hours.

LG: What are some things you look for when making a selection about what to paint?

HS: I live in beautiful rural area just north of Lake Ontario. The rolling hills, plots of mixed forest, farmlands, roads and lakes make this place endlessly interesting to me. This is home, so I’m interested in poking my nose into all sorts of areas within a 50 mile radius. I walk every day and this sampling of place, atmosphere, and light provides the incentive for the daily picture. I make little drawings of motifs, or I take digital photos, or I might make a conscious mental note about something experienced to base the painting on, and then paint exclusively from memory. One of the influences of growing up in Saskatchewan is that I am always looking far into the distance; this seems to provide some sort of emotional solace…it’s comforting. But as I walk all sorts of arrangements present themselves. Usually a strong painting motif will have 3-5 things in relationship, and I’ll note those. The painting will be made within a few hours of returning home. The motifs that I notice most often seem to carry some sort of strong emotional load; they seem important to me for some strange reason that goes further than pure design. From the daily excursion (it’s usually a walk, but it could also be a drive) a number of ideas will have been noted, and I will select only one for the daily painting session. Painting on location works a bit differently because I commit to a spot and dive right in to the painting. Sometimes I will roam around for quite a while, searching for a place that not only looks right, but ‘feels’ right.

LG: You currently paint landscapes from life as well as in the studio from memory or imagination. In what ways does your studio painting differ from your outdoor painting? How do you determine what type of painting you’ll work on.

HS: Ideally I produce a painting per day, but every so often, I’ll miss a day. My overall aim is not so much to create a masterpiece…but to keep producing. So it follows from this that the most important thing for me is to maintain my daily energy for the task. Whenever repetition threatens to create a sense of inevitability either in approach or result, I try to break the pattern. Although most of my work is small in scale, I’ll often vary the sizes just a bit, from piece to piece. You wouldn’t think so, but this makes a huge difference. I’ll also vary the method used, collage plus paint overtop, rather than pure painting, for example. Or I might decide to work on location rather than in studio. I’m reacting to impulses based on my response to the painting just previous, to try to build maximum excitement and anticipation for the task into the coming work. That first decision about what to paint and how to do it, is about courting surprise, which is really helpful in keeping the whole enterprise going. This process is like a diary. I don’t worry about the paintings much. I know that there is a way to effectively resolve each piece, and I work hard to achieve that in the session…but then I move on. Once in a blue moon I will come back to work on a piece after the fact, but this only happens if something unusual interrupted my concentration during the initial work session.

The paintings produced on location do differ from the studio pieces, although these differences might not be glaring at first glance. The length of each work session remains more or less the same in each case…..usually a bit under 2 hours. My painting sessions are a bit manic in both situations. Painting is not relaxing! Once I start, it is all systems go, with no interruptions. Painting on location is even more intense. There are more procedural unknowns…..wind, bugs, blinding or changing light, intense heat, interruptions from passersby……all are manageable, but they also cause one to key up in terms of energy. I usually feel a great sense of relief once I establish an initial flow in the outdoor painting, because the whole thing is a bit precarious after all. I’m usually even more impulsive in the outdoor pieces, and I work even more quickly. Failure is not an option in any of my pieces. This is the time, and this is the place, and the picture will be resolved in some satisfactory way….so I never abandon anything. It feels like a bit of a work-out after a plein air session, but it’s a very satisfying feeling.

LG: Please tell us some of your considerations when using color in your work? What sort of paints do you put out on your palette?

HS: For the past number of years I have been using these colours: ultramarine blue, Prussian blue, light blue violet, light blue permanent, Naples yellow, unbleached titanium, titanium white, raw umber, burnt umber, ultramarine violet, carbon black, chromium oxide green, terre verte, hookers green, viridian green, cadmium red middle, cadmium yellow middle, as well as a variety of mixed pinks, greys, and blue greys. I always use acrylics, but I often mix up the brands so that there isn’t an annoying chemical uniformity to the colours (that’s a tip from Canadian landscape painter Dorothy Knowles). Colour is the great mystery and the never ending fascination of painting. No matter how much you think you know, you can never really understand it fully. The colour in the work has to create a relationship that seems to pulse. Whatever else I do with colour, I’m always watching for the life in these relationships. And being watchful is the key, because often beautiful things will happen with colour when you least expect it, and you have to be ready to decide what to do with it when it appears. I started mostly as someone who drew more than painted, so that might explain why I am very attuned to value. In most of my work there will be a clear range of light, middle, darks, and balance will be created this way. In most pieces I want to see a richness of greys, and pure colours are often reduced in saturation with opposites or relative opposites. I’ll usually draw a bit first, either in pencil, or small brush, and I’ll quickly under-paint with a warm, often mixed with unbleached titanium and a touch of cadmium red. These things vary over time, but that’s what I’m under-washing with these days. I also like to vary the thicknesses of paint in different areas of the work.

LG: I understand you often make collages from handmade colored papers with paint leftover after a painting session. Can you tell us more about this process? Do these collages also help inform your landscapes in some way? What could you say about what this has done for you in terms of how you approach color in your paintings?

HS: I came to landscape painting in some strange back alley way. I got here really through all the things I tried before which included pure abstract painting, as well as an odd kind of story telling. My landscapes don’t fall in line with California landscape painting, or some of the earlier traditions found in the eastern US. Perhaps my largest influences would be French late 19th and early 20th century painting, and abstract expressionism. So I make up things, and improvise a lot. I am always very watchful for fascinating surfaces that happen with paint. Often, I’ll stare at my painted collage papers and wonder how I can make a satisfying work with one or two colours of paint over a surface. Often the beauty of paint and surface can’t be well seen when there are so many complex facets in the painting. I am open to all sorts of concerns of the abstract painter, without actually being one. I have 1000s of painted collage sheets and sometimes I play with them when not painting, looking at colour and surface relationships. I start a collage by cutting and gluing 3 or 4 pieces of paper that form the entire composition. Although collage is a bit tricky and crafty, this process actually makes the procedure looser, because surprise and change can happen so quickly. It encourages impulse! And one can arrive at very surprising colour relationships within the first few minutes of the piece–relationships that one would never have achieved without the element of chance being at play.

The other thing that’s important to say here, is that variety of method is very important to me. I am always looking for new ways to make the picture. Again, the main reason is that my aim is to simply keep producing every day; boredom must be kept at bay. And predictability will create boredom in the long run, and lead to a loss of energy for the task. I want to avoid this, so I’m always looking for some suitable variety that will reinvent the procedure in subtle ways.

LG: What are some thoughts you have about deciding on the underlying structure of your painting? Is this something you study before starting or does it come after you’re underway–out of the paint?

HS: The structure is very important and is usually the very first thing I think about when looking at the landscape with a view to making a painting. When I make my little 1 minute on-site diagrams, all they really show is the composition, a few scale relationships, and one or two notations about major distribution of lights and darks. Even when I’m merely looking, without drawing, it’s like there is a schema or grid in front of my eyes that is always composing. But, when I do the more abstract compositions, usually in collage, or collage and paint, they most often begin with a mood, or a feeling about something; composition and overall structure are not determined until later in the work.

LG: Does painting from observation offer you visual surprises and compositional possibilities that are harder to get from studio invention? Are there ways you could achieve something similar in the studio through “accidents” or approaches to painting methods as well?

HS: The observational pieces I produce on site, as well as the ones I make in studio have more similarities than differences. However, the pieces that are made purely from invention, or from imagination or inkling, and that are more abstract, seem very different because they don’t attempt to record the visual world. And I need to make these as well. Thoughts, emotions, responses to daily living, to things seen and experienced, become intense and need to be dealt with. So when I make these pieces I hold on to an experience from life, and have almost no preconceptions about how the picture should come out. Colour, design, method…everything is negotiable and all is improvised, while mulling the central idea. These pieces harken back to purely abstract work I was doing many years ago. The surprises are always welcome. Doing a work such as this the next day after doing a piece on location, is so helpful because it allows painting to fully address all aspects of my life. Techniques from one method also influence the other, which prevents me from getting stuck in a rut.

LG: How much does working on small paintings in one sitting influence your decisions about how and what you paint?

HS: I have always been a painter who completed the work in one sitting, right from the start. Even when I was doing 4 x 5 foot canvases of urban landscape, I started about 10 or 11 in the evening, and finished by 6:00 a.m.. Everything I want to achieve can be done in one sitting, and working in that intense way allows a lot of intuition to come into the mix. Minute description in painting can take a lot of time to execute, and it can become laborious and tiresome, so I usually prefer to suggest rather than describe. But I do like to use some description because an observational work can also be too vague or generalized without it.

LG: Is creating or responding to the mood of scene or your emotional state of being something that interests you?

HS: Yes and yes. When I stop and am impressed by something I see in the landscape, and make a note for later work, it is always rich in mood and dramatic in some way. That initial feeling is addressed in the painting. Many of my pieces are a visual record in a way, but they are also distortions resulting from interpretation. And this brings me to an important dichotomy. Some of the paintings I make refer very much to what is seen. Some that I make refer almost not at all to what is seen, but rather, to what is felt or thought about. And so there are two kinds of paintings, that in a lot of ways, influence each other. Alternating between these 2 ways of working helps keep my energy high because it builds difference and innovation into the process. This alternating also addresses the fact that a painter is not just an eye, but an entity that processes the world through emotion, thought, and memory as well.

LG: How different is your ability to “lose yourself” or get out of your head, when painting from nature compared to when you paint from memory? Is thinking while painting something you tend to welcome or avoid?

HS: I can easily lose myself in both kinds of painting. Doing some thinking while you work is unavoidable, but that said, I do try to keep it to a minimum during the actual work session. There will not be any long pauses of thinking or going back and forth in my mind over a possible decision. I have always worked quickly and instinctively and that has clearly helped establish a flow in the process, and perhaps got me addicted to this way of working. The process of the picture’s unfolding is for me largely guided by abstract concerns related to the operation of the elements and principles of art. There are many ways to mess up, but there are also many solutions, so I know the picture will come together in some satisfying way. The painter David Milne said something to this effect: “a painting’s success is determined by energy, and the energy in the creation of a picture is always going up and down; it is never stable, like intelligence”. For this reason, when I do find myself pausing and rethinking too much, I know to automatically speed up, remove overthinking from the process, so as not to lose any momentum. Once the picture is complete, and the session is over, the work is always put up and remains in front of me until other pieces take its place. All types of thinking, evaluating, and planning about further directions happen every day and all day. And all this sorting is valuable and feels entirely productive, but it doesn’t enter into the work session in a way that disrupts flow.

LG: Do you listen to music while painting? Do you ever worry this could adversely affect your feelings about how the painting is going or overly influence your decisions?

HS: I do often listen to music, but more often I listen to talk radio, specifically CBC radio, the national broadcaster of Canada. The thing I’m really after when in a painting session, is to feel the sense of flow. Once that starts to happen, when there is no second-guessing, when everything happens easily and naturally, I don`t worry or fuss about anything. I often talk back to the radio in some ridiculous, outrageous way, or laugh, or maybe sing or hum if I have music on. It helps establish the flow, and doesn’t interfere negatively at all.

LG: What gives a painting a feeling of authenticity? What thoughts or suggestions can you offer about how to avoid cliche or sentimentality?

HS: It seems so easy to fall into a rut. Picasso said artists should avoid being their own connoisseurs! And, that most artists learn to bake a cake, and then they spend their lives baking the same cake! It seems so true. It is difficult to say how one achieves authenticity, but it does seem to have something to do with continually trying to go beyond one’s own limits. And this is easier said than done, because of course, we are bound to repeat ourselves to some degree, even to a great degree! But the openness to a new experience, and new ways of doing, has to be there, and we have to constantly know that there is something we haven’t done yet, that we have to get to. We are, after all, trying to find something. The authentic has to do with how deeply and intimately we go about this search.

LG: How healthy is landscape painting in Canada these days? Do you think the arts are supported in Canada better than here in the US?

HS: It has always been extremely hard being an artist in Canada. Remember that Canada has a much smaller population than the US, so opportunities are not as many, and galleries are fewer. I was very lucky in my early years to receive an important Canada Council Grant, as well as other grants, and these made a difference. I don’t often see the landscape in Canada now being painted in a strong way, but then my focus these days is more international. I look at artists from all over the world, and a lot of them are American. Most of the people I sell to are also American.

LG: With the daily news about new levels of craziness in the world, how hopeful are you about the future of painting in all of this?

HS: I don’t know if I have any great hope for the longevity of civilization as we know it. We don’t seem to have any effective ways for tackling and resolving large societal and environmental issues. That said, I don’t have any concerns about the survival of painting as an art form. Painting is a simple and regenerative form, open to all kinds of meaningful invention. Painting hasn’t become either more or less important in my time; it sure hasn`t died. I see it as one of the few pure and hopeful aspects of humanity. But of course, painting will only survive as long as we will.

LG: Your online sale of artwork has been quite successful and I suspect many painters have thought about how this might be a good alternative to the usual gallery route. You’ve talked at length about this in other interviews such as the one with Antrese Wood at Savvy Painter. Your talent and vision combined with the affordability makes buying your work very attractive. However, for many other painters there are significant obstacles to selling online. You got started years ago, and gradually built up a following through a wide variety of venues.

Getting into an established brick and mortar gallery is probably just as difficult if not more – than successfully making a living from selling artwork online. I’m curious to hear your thoughts on surviving as painter and if you have any suggestions for someone starting out today to sell their work online, is this still feasible or is the market too saturated?

HS: This is a very interesting question and such an important one. The bottom line is that artists have to survive. Perhaps the best way to manage this question is to simply relate my own experiences. From the very start, I wanted to make a life in painting, to do it every day in a serious way. After I finished my MFA, and did some sessional studio teaching, it became clear that full time university teaching jobs in art were scarce in that time period. I did other jobs (hotel night account audits) and painted, and had good gallery representation for a time, but I always found galleries problematic for a variety of reasons. Work was sent to a variety of galleries at my cost, as was framing, and work was kept over long periods of time, ultimately with not enough of a consistent financial return to build a future.

It would have been different if I was selling out shows at high prices, but that wasn’t my case. I decided to make my living elsewhere and taught art at a wonderful private school for 26 years. Certified Canadian teachers are well paid and the pension benefits are excellent. My teaching years were very busy and I always used free time to make paintings. As the internet became more important over the years, and Ebay became a key site, I thought it would be interesting to try to sell paintings there. It worked but only to a degree, but my wife and I then ended up selling rare and out of print books on Ebay for many years. It was amazing and profitable fun in the heyday of Ebay! The bookselling experience may have forever hooked me on online commerce. When Etsy came on line I thought the site was well suited for selling my paintings, and I have been with them since 2006. I list new work there on a daily basis. I also set up a website and list there as well, so that people have a choice about where to buy. I also list on Instagram and on FB and chat in both places. Every piece also gets posted on twitter and Pinterest.

Selling very regularly online has helped me in all the important ways. But earning my primary income as a teacher freed me up to experiment with the marketing of my art. Online venues are definitely not for everyone, and certain prejudices have to be rid of even to consider the proposition. A whole change in thinking might be necessary. I’m prolific and have always worked quickly. A painting is made in one session, and the pieces are small, on paper, easy to package, and relatively inexpensive to mail. The scale very naturally went smaller during my teaching years, because available time spans were shorter. I liked the smaller pieces better than the larger ones anyway, because so many loose, intuitive things happened in them. I`ve always loved working on paper. And I was not at all concerned about charging a lot of money for the work. I simply wanted to sell it and get it to people who wanted it.

All of these points made the work appealing to a young, informed and interested, but not financially rich market that was the keystone to Etsy. Instagram and Facebook have certainly helped drive my sales on Etsy as well. It is entirely possible to starve to death waiting for someone to buy your work at high prices. I found it much more appealing to sell hundreds of pieces at lower prices (most sell for $100.00 US now) and this has also provided motivation in producing work; one just feels more like a contributing, vital part of society when you`re mailing packages with artwork every day. This online art selling was an experiment that had a thrilling result. I do feel it’s important to continually experiment with venues and to be persistent in everything. I spend a lot of time on my marketing, but much of it is very social as well, so it doesn’t feel like work.

Not only do I love and respect Harry’s work, he is a generous poster in social media creating a community of sorts with his work connecting so many of us.

I have only discovered Harry’s work within the last six months and both he and his work have been an inspiration. I too work to a smaller scale which, despite the diminutive dimensions, allow me a degree of freedom that I find elusive in larger scale works. That is all down to Harry Stooshinoff influence.

Thank you for this interview! Harry is an inspiration as a painter and an enlightened human. I so appreciate the tender, insightful story of this tender and tenacious life of Harry’s. It reminded me again that artists are different, and often see the beauty of the world in a most special way.

Can I assume that Harry’s work does not require glass? Does he apply a final coat of varnish? If so, what type? Thanks, Susan Rogers

Hi Susan. Sorry for the really long delay in responding. My paintings on panel do not require glass, but all my works on paper do. I apply 2 thin layers of Liquitex gloss varnish only to my tiny (2.75 x 2.75 inch) pieces, and that’s because these are presented as fridge magnets, and are designed to take continual handling.