Gerry Bergstein is a well-known Boston painter and teacher who has hugely influenced many artists since the 1980s. I recently was viewing his work online and became re-enchanted by his astounding talent and wide range of art historical references, styles, processes, and subject matter. His morphing and juxtapositioning of visual and cultural opposites has made for a highly inventive and personal art unlike any other. I particularly love his resistance to doctrine and his contrarian takes on the possibilities for art. I decided to ask him for an interview and was incredibly delighted and grateful when he agreed to talk with me on a Zoom call.

The late Francine Koslow Miller wrote in a 2002 Art Forum review of a Gerry Bergstein exhibition at the Howard Yezerski Gallery.

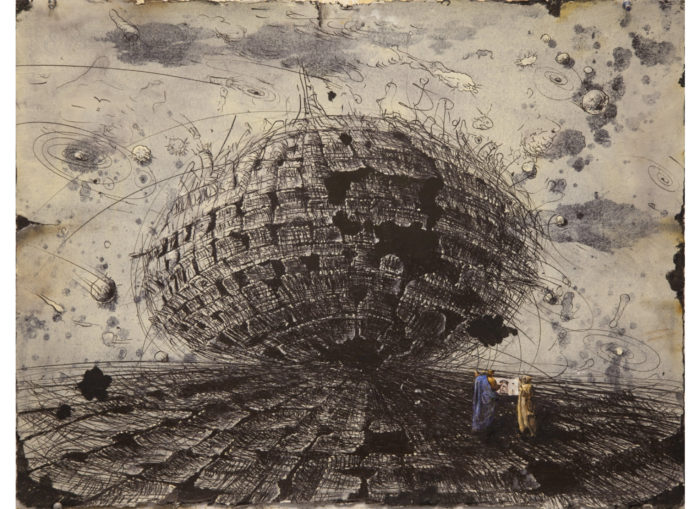

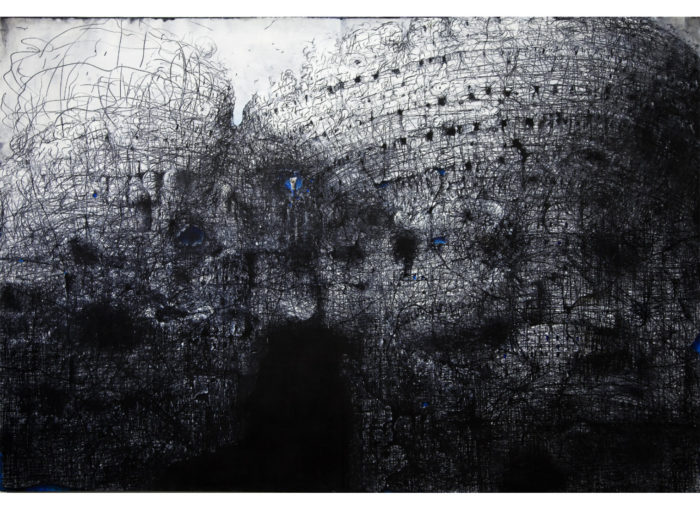

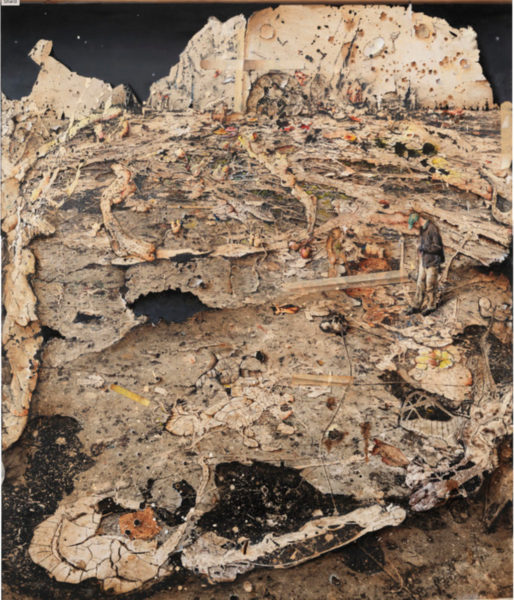

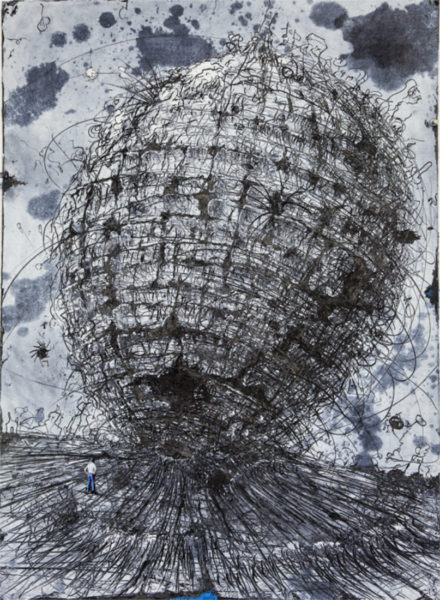

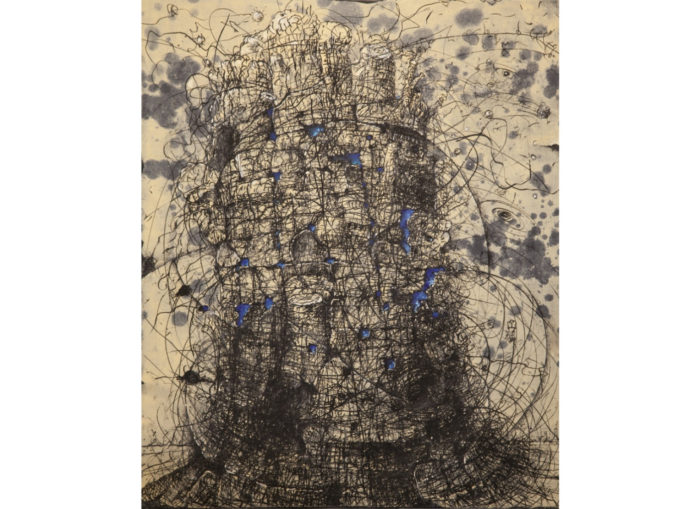

“Bergstein pursues darker concerns in his vaguely architectural black-and-white paintings of mounds. An amalgam of decaying mountain, medieval building, and phallus, the mound always appears to be imploding or exploding in these works, which resemble pencil drawings on damaged paper (here the artist etched lines into a prepared surface of black paint overlaid with white). For Mount, 2002, Bergstein moved his stylus back and forth across the highly detailed central form in strokes imitating the rhythmic gestures of a cellist. In the monumental Self-Portrait as Tower of Babel, 2002, the mound is under siege, pierced with luscious black holes; it begins to topple before a romantic cloudy sky. References to Leonardo’s Deluge drawings, Brueghel’s Tower of Babel, and Piranesi’s ruins abound in this anthropomorphic citadel, whose stony skin appears to be ripping apart. (It’s hard not to think of the World Trade Center as well.) Hidden among the gaps in the tower are self-portraits and other small images: insect caricatures, a paint tube, a Guston “eye,” a thumb, a rocket ship.

In these works Bergstein equates nature and culture with personal ambition and ideals. The mounds may posit civilization as a beautiful pile of garbage, but they also suggest Bergstein as existentialist antihero at the foot of his own mountain of ambition (his goal being to achieve global relevance while staying true to himself). As Albert Camus ends his Myth of Sisyphus: “This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Bergstein likewise transforms the torment of his struggle into victory.”

Nicholas Capasso wrote in his essay Expressionism: Boston’s Claim to Fame

(Originally published in Painting in Boston: 1950-2000)

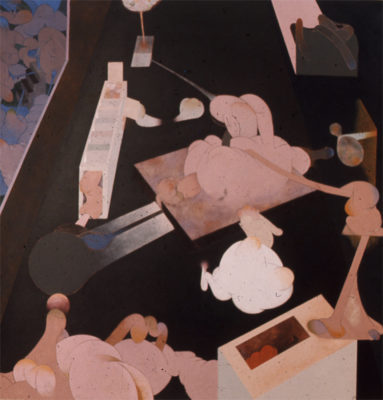

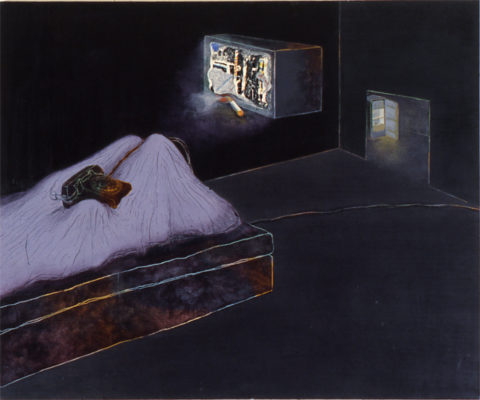

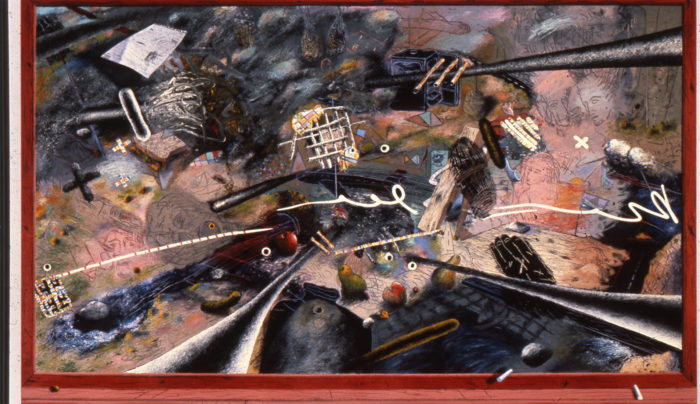

“…Bergstein distilled all these sources”(Max Ernst, Rene Magritte, de Kooning, Gorky, and Guston) “…into a personal approach in which Surrealist techniques of free association and irrational juxtaposition were brought to bear on expressively distorted images created with an amazing facility of craft. This artist could draw and paint like an expressionist, an Abstract Expressionist, a veristic Surrealist, and a trompe-l’oeil master—and convincingly combine these styles on a single canvas. During the eighties, this stylistic spectrum was matched by an equally diverse range of imagery drawn from art history, self-portraiture, nature, popular culture (especially television), and the suburban cultural landscape—again, all on the same surface. “

“…I continued to explore the spatial tensions obtained by juxtaposing thick and thin paint. I had always been interested in juxtaposition of images (Magritte). I was finding that juxtapositioning of different surfaces could be just as strange and surreal.”The point of Bergstein’s technique and approach to imagery is fundamentally humanistic and expressionistic. He seeks to express ineffable mental states conditioned by his own experience of the world—an admittedly chaotic and confusing world—as a model for emotionally apprehending larger issues in contemporary society, psychology, epistemology, and ontology. These weighty themes, though, are always tempered by humor. As the artist explains it, “My goal is to do for painting what Groucho Marx and Alfred Hitchcock did for movies and television. My work is a representation of the paradoxes, ironies, and absurdities of our media-bombarded culture, translated through the language of paint.” Elsewhere he wrote, “I still wonder how the unexplainable creation of the universe, the light-speed movement of all those subatomic particles, and billions of years of evolution could have led to squeezing the Charmin, tax returns, life insurance, the art world, and other strange results. If, as Einstein said, ‘God does not play dice with the universe,’ maybe he was playing bingo.”

From Gerry Bergstein’s website:

Bergstein’s work contrasts the awesome and the trivial, the high and the low, the manic and the melancholic using sources from Brueghel to “The Simpsons.” He is the recipient of an Artadia grant (2007), a career achievement award from the St. Botolph Club (2007), and a four-week residency at the Liguria Study Center in Genoa, Italy (2006). His solo shows include Gallery NAGA and the Danforth Museum; Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston (’04, ’02, ’99, ’97); Stephan Stux Gallery, NY (’99); Galerie Bonnier, Geneva, Switzerland; Zolla Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, IL; and the DeCordova Museum, Lincoln, MA. He is represented in the collections of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; MIT; DeCordova Museum; Davis Museum at Wellesley College; IBM; and many others. He has been reviewed widely in the local press as well as Tema Celeste, ARTnews, Art in America, and Artforum. He has been on the faculty at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for over two decades.

Larry Groff:

What were your early years growing up like? What was your family like?

Gerry Bergstein:

I grew up in the Bronx and Queens in New York, where I stayed till I went away to college and left New York. We lived in Bayside Queens, which was nothing like Manhattan. I would be very surprised if anyone else on my block ever went to the MoMA, for instance. However, my father loved to draw and paint; my mother loved music and literature. I may not have become an artist if not for their support. Like when my mother told me to go to see that Max Ernst show. If my mother were alive today, she would have become a Music or an English professor, but she didn’t get to go to college, sadly. My father was an accountant. When he was younger, he did a lot of wonderful realistic drawings of his family; many of them are hanging in my home. He might have made it as an artist, but his family discouraged it, and he needed a job to support the family. He continued to draw and play the piano like Mozart, and Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata was one of my favorites. So I grew up around classical music and older art.

My parents didn’t get contemporary art. One time, when I was much older, I went with my mom to the Guggenheim, which had just reopened with a Dan Flavin show after having been closed for a time, and the first thing she said, “Well, I guess they don’t have the art here yet – they’ve just put the lights. (laughs) And so, part of my issue with high and low art is that I have that skepticism of my mom, but on the other hand, I also like a lot of that stuff. Eventually, I came to like Dan Flavin. So I have mixed feelings about high and low, and I like combining them. So I’m a contrarian I always see both sides of everything, which is both fun and healthy.

LG:

I read that your mother encouraged you to see a Max Ernst retrospective at the MoMA in the early 60s. I was curious so I looked online to see if there was any information about that show and found the catalog for the show on the MoMA website – I found a quote that seemed like it could have also been describing your work.

“From Ernst’s frottagee, decalcomanlas and flows of pigment emerge a procession of visions sometimes obsessive and often prophetic: new landscapes inhabited by new phantoms and animals; new adventures and new terrors revealed by the rarest and most significant dreams. The world of Ernst can be turbulent, eruptive and violent. It can also offer with irrational lucidity and calm, an explanation of the magic of objects, the black humor of human foibles and the apparition of unseen presences. Like the looking glass, the Imagined world of Ernst is a reverse image. It is also a universe.”

Can you say something about your interest in Ernst and any other influences that are most important, especially the surrealists?

Gerry Bergstein:

I used to do these little abstract, very detailed ink drawings. They were mostly abstract, but my mom must have recognized something about their complexity, so she sent me to the Max Ernst show, which blew me away. I agree with the statement you gave.

“new adventures and new terrors revealed by the rarest and most significant dreams, the world of Ernst can be turbulent, eruptive and violent“, is something I’m very interested in as well as “The magic of objects”. Magritte put it differently. Magritte did a painting of a wedding ring floating on top of a piano. He had this idea of secret and magical affinities between objects, you couldn’t put these affinities into words, but I love that idea. I guess that’s a whole Surrealist idea. And the last line that Max Ernst’s work as a universe also rings true to me. Although my work is a universe–it’s the universe inside my brain and my studio. Maybe the universe is in the brain of the beholder.

I recognize stuff from working on a picture. I’m not very good at observing reality in nature. I’m kind of bad at it, maybe, because I’ve never done it that much. However, what I am good at is exploring my brain visually in response to the marks I make, I have this sgraffito process, in which the paint stays wet for a month, and I can draw into and out of it. I combine different things. I’ll leave the studio and then come back the next day, and it’s telling me something, to enhance this or to deemphasize that. I’m pretty good at that. It’s just who I am, which involves free association and rorschaching. Gregory Gillespie talked about rorschaching a lot and is similar to what I do – but different.

Larry:

I’m wondering if the painter Ivan Albright has some affinities with you? It’s not surrealism or rorshaching, but the intensity and drive of his vision perhaps are related to you and Gillespie’s work.

Gerry Bergstein:

Absolutely, I think the ironic thing is about these polarity things I went to Chicago and saw Albright’s painting, That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door), a couple of years ago. I saw a picture of it in a book when I was a teenager, and it totally blew me away, but when you get up close to the actual painting and look at one square inch of that door, it looks like a microscopic Jackson Pollock. So many little interesting marks. I like art that refers, intentionally or not, to the whole of Art in an original way.

Gerry Bergstein:

One more thing about surrealism, do you know the painting Hide and Seek by Pavel Tchelitchew?

LG: Sure.

Gerry Bergstein:

I loved it as a teenager, and then in 2017, I retired from teaching, but in 2019 I was persuaded to teach a grad seminar, but I was shy and nervous about my hearing and was afraid I wasn’t up to date enough. So to soothe myself, I visited MOMA just two days before that class started in 2019. And I walked up to the third floor and there was Hide and Seek hanging again after it had been in storage for like 30 years. The wall text said that in 1961, which was the year I first saw it, was voted by the public to be the most popular painting in our collection. Well, I thought that was such an affirmation. I don’t love it as much as I used to, but I thought, ‘what goes around, comes around’. It suffered from acclaim, rejection, and re-acclaim. I think that’s so great.

Like it or not, the politics of art aesthetics in the art world come into my work, in a very ambivalent way.

LG:

You studied at the Art Students League?

Gerry Bergstein: I studied at the art students league for a year with Harry Sternberg. Who was a great teacher. He taught me what freedom was. Harry Sternberg was friends with Jack Levine. And his work, at times, was a little bit like Jack Levine. Edwin Dickinson was right next door. And Lennart Anderson was there at the time. I moved to Boston by accident. I had no clue about the Boston expressionist school, but I thought it was ironic that I moved to Boston and became somewhat involved with that tradition and Boston rather than New York.

LG:

Why did you move to Boston?

Gerry Bergstein:

I had to go to a place that was affiliated with the college. Otherwise, I would have been drafted.

LG:

What was your experience going to the museum school (School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University) back then? You studied with Henry Schwartz, Barney Rubenstein and Jan Cox, a Belgian Surrealist painter. Was Barney the main teacher to help you learn realist and trompe l’oeil painting?

Gerry Bergstein:

Henry Schwartz taught me more; he had these bizarre setups that were surreal, and they reminded me a little bit of some of Bruce Connors’s early work. Surreal setups with musical scores and portraits and different things pasted it together, and they were delightful and hilarious. I learned a lot from that project and I guess that’s what got me interested in trompe l’oeil. Barney was more of a friend. I adored Barney and learned a lot from him, but it wasn’t a teacher-student thing; it was more long conversations. Plus, I loved his work. Jan Cox awakened certain things in my imagination. I took a design class with him, and he was sweet and accepting of unusual ideas.

I experienced the museum school in different ways. I was a student there in the last two years of the ultra academic curriculum to the student revolution in 1970, which changed that completely. Soon after that, Clement Greenberg began to hold sway in Boston with new faculty at school and Kenworth Moffett, a Greenburg acolyte, being hired as the M.F.A.s first contemporary curator. Clement Greenberg was seen by some as being at the apex of modernism in Boston; although his influence was already in decline in New York. I liked modernists like Morris Louis and Jules Olitski but I thought that the idea that you couldn’t show realism or surrealism due to some second-rate philosophy was just infuriating.

Even though the museum school was really academic for the first three years I went there, I managed to find my way through that, and I’m glad I had some exposure to, you know, real academic drawing and that kind of thing. Even though I wasn’t that great at it,

LG:

Do you think painters need that kind of academic training?

Gerry Bergstein:

That’s a very good question. The museum school changed radically in 1969. The student strike during the anti-war movement. The head of the school was fired, and a new head of the school replaced him, and policies were changed so students could make their own curriculum; you didn’t have to take any course you didn’t want to. For the first few years, the results were disastrous. But eventually, it sort of worked itself out. Do all artists need that academic structure? I’m not sure, I think I needed it, but I don’t know. What do you think?

LG:

When I was in school, I sought out traditional realist training. Some of the abstract painters whom I admire the most also went through that academic rigor. But then there are other abstract painters who were self-taught or didn’t get much academic training, who I also like. So I don’t think there’s any right way to learn art, although I do think it’s critical to learn art history well. I don’t believe in just one right answer and try to resist art doctrine.

Gerry Bergstein:

There’s no one answer; I absolutely agree. Yeah. I mean, I think de Kooning was a great draftsman and I adore his early work; I don’t think Pollock was such a great draftsman.

LG:

However, Pollock did study with Thomas Hart Benton, who helped give him an understanding of structure.

Gerry Bergstein:

That’s exactly right. I think his compositions have something a little bit in common with Benton’s compositions.

Pollock knew what he was; he knew the terrain. Kids going to art school today get very little of that, although maybe that’s a gross generalization, I don’t know. I think it can still be possible to get it if you want it enough. Gregory Gillespie once said to me that despite going to the San Francisco Art Institute, he considered himself self-taught because it was strict abstract expressionism when he was there and didn’t offer much in the way of learning how to be a realist painter.

LG:

Maybe that’s not always such a bad thing sometimes. Gillespie may have taught himself the way he wanted to paint realistically, but his time at San Francisco Art Institute eventually helped him become such an amazing painter; he must have gotten something out of it, just not realist painting chops. Gregory Gillespie is among my favorite painters.

Gerry Bergstein:

I remember a story about Chuck Close, whom I think went to Yale. He was a pretty good abstract painter back then. I heard him speak once at Harvard, and he said, The problem with abstract painting was that he would leave his studio thinking, ‘this is the best thing that’s ever been done in the world’. Then he would come back the next day, and it looked like complete crap; he wanted to do something that he could be verifiable that he was doing it right. He also wanted to get as far away from de Kooning as possible. So if de Kooning used a lot of color, he used black and white. If de Kooning was totally into the act of painting, he was watching TV while he was painting. His move to be self-consciously away from that is interesting to me as well. Later on, he joked that he had made more de Kooning’s than de Kooning himself with all his little “colored pixels” in grids that you see in his later work.

So we’re on this sort of lineage. Probably if I hadn’t taught, I don’t think I would be thinking about the stuff much at all, but since I taught, it’s a crucial thing to me.

LG:

It’s probably not helpful to always be reacting against something or rebelling. At some point, you have to decide what you want to be.

Gerry Bergstein:

The act of rebellion in itself doesn’t guarantee good art. There has to be some sort of element of love and discovery in the work, not just rebellion. I need both love and rage.

LG:

How did your career as a painter evolve after finishing school? What was life like for you back then? Were you able to paint full-time? Did you start teaching right away?

Gerry Bergstein:

when I first got out of school. I got a traveling fellowship and spent four months in Europe, which was life-changing. When I got back, for around five or six years, I worked full-time as a picture framer. I didn’t get much time to paint then. I had to make a living, but I made it a point never to give up.

In 1973 I got a grant to go to an artist in residency in Roswell, New Mexico, for six months. They gave you a stipend, house, and studio. I went there and got to know some serious artists. We became friendly. I got to know their work habits and know what it was like to have time to work, which was terrific.

When I returned in about 1977, I got a job teaching at the night school in the Museum School. But it paid five dollars an hour, my parents would send me money once in a while, but I was living hand-to-mouth. I made friends with some artists; Miroslav Antic was one. He was a teacher at the Museum School. He was much pushier than me and had a friend who opened a gallery. He brought this friend to my studio, who then offered me a show. I also got a job teaching at Concord Academy, which was a little better than being a picture framer as it was part-time but a little bit more money. I was struggling along. And then, I had a show at Lopoukhine/Nayduch Gallery in 1979; nothing sold, but there was a lot of interest from artists, and it was very encouraging.

Grants, so I was beginning to do okay. I’m a very shy person. For a time, I would break out in a sweat just walking into a gallery, let alone asking them to look at my work.

I went to New York and fell in love with artists like Susan Rothenberg, Robert Colescott, The bad painting show at the new Museum, and Philip Guston, Oh my God. I thought this was the ultimate negation of the Greenbergian tyranny.

LG:

Has Philip Guston’s work influenced you in some way? Can you talk about this a little?

Gerry Bergstein:

When I first saw Philip Guston in 1975 at BU when he first started doing the Klan heads and I loathed it, but then in 1979, I was doing this self-portrait of me covered with a blanket in bed, and the shape of the blanket was a lot like one of those Klan hoods. There was a cigarette with really thick smoke coming out of it; then I remembered that show, and like it was love. I still love Guston. I became very excited about this new direction in painting. My friend Miroslav was kind of a mentor then. Henry Schwartz, whom I adored, rejected that work completely, but I didn’t mind because I knew Henry loved me.

I got into a show in 1981, Boston Now, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, where every year they would put on a show with about eight Boston artists; it was really exciting, and then I got into another Boston Now show the next year and then got picked up by Stux Gallery. After that, I started selling every single thing I made. From about 1981 to about 1995. I sold everything. As a result of this, I was able to teach full-time at the Museum school because I was showing. Teaching at first was just a day job, but then I learned a lot from it, and it was really fun.

LG:

Do you see yourself as part of a continuum of the tradition of Boston Expressionist painting, such as Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine, David Aronson, Karl Zerbe, Henry Schwartz, and others after them?

Gerry Bergstein:

I have somewhat mixed feelings about the Boston expressionists. I love Hyman Bloom. You know, people like Arthur Polonsky and David Aaronson, I thought they were a little too slick, too crowd-pleasing, almost too romantic, but I guess they’ve all had a big influence on me. Strangely enough, the year I quit teaching, no one had looked at those guys for decades, I decided to do a slide show of all of them for my class. The students came up to me and said this is the best art we’ve seen in years; we love it!

LG:

Would you call yourself a Neo-Expressionist, or do you reject being labeled as part of any particular school?

Gerry Bergstein:

Would I call myself a neo-expressionist? I did when I was in the 80s. Along with Francesco Clemente, Jorg Immendorf, David Salle, and Julian Schnabel. I was interested in some of their work; I placed myself in that spectrum. But there was a lot of bad Neo-Expressionism too. Is Philip Gustin a Neo-Expressionist? I don’t know

LG:

I think his late work could fit in with that on some level. I anticipated that you might react against being labeled as a Neo-Expressionist; I thought maybe you’d resent being labeled, That you’re in a school of one.

Gerry Bergstein:

I’m more into my ancestral lineage. Maybe beginning with Bruegel and Hieronymus Bosch, going on to Piranesi, Velasquez, and Goya, and then up through Ensor, Rousseau, the Surrealists, the German expressionists, and the Abstract Expressionists like de Kooning. Arshile Gorky, Gorky was a big influence, and then the Neo-expressionists are also my forebearers.

But what you want to do is to add your own take to whatever you’re doing–you want to make it your own. You’re advancing the tradition a little step at a time. it’s a very broad tradition. I mean includes near-total abstraction and also artists like Bouguereau and Fragonard. Late in life, I suddenly fell in love with Fragonard, who is almost my complete opposite. His sentimentality is so blatant that I just can’t help but love it. However, Boucher, I don’t like as much.

LG:

I don’t know if you’ve seen the new Artificial Intelligence image software where you give text prompts to combine imagery gleaned from millions of images on the web. I saw recently where someone combined a Bouguereau nude and some kind of blue monster.

This sort of AI surrealism is, more often than not, quite dreadful, but I still think it could be useful for generating ideas visually. Kind of like drawing thumbnail sketches. I tried this a while ago, writing in the prompt, Picasso painting of the Tower of Babel, to see what might come up. It was interesting what it chose to do.

Gerry Bergstein:

It’s fascinating and terrifying at the same time. Is the painter going to be like the chess master, who can no longer beat the computer anymore? I don’t know. But what terrifies me one year, I can fall in love with the next.

LG:

I guess the point I’m thinking about is that so much of our lineage is open for reinterpretation and making it new. Like maybe making hybrids like medieval-neo-expressionism or cubist-photorealism. Technology, as well as our contemporary mindset, allows the past to continue in new, exciting ways. Painting is far from being dead.

Gerry Bergstein:

Painting has been declared dead for well over 100 years. (laughs)

Past and future generations examine the same issues through the lens of their culture and through their technology. Some things may evolve technically and culturally, but the big issues like life and death, love and sex, power and rage all stay the same.

LG:

That’s a very good point.

You’ve talked in the past about your fascination with juxtaposing contrasting imagery and ways of applying the paint. You often paint trompe l’oeil elements, especially flat things like tape, over or alongside expressionistic elements. You might also incorporate flat, cartoon, or child-like drawings, collage, and sculptural pieces next to realistically painted fruits. You seem to revel in combining the high and low-brow, sacred and profane, and the banal with the extraordinary. You once stated that your “paintings contrast the awesome and the trivial, the historical and the personal, the manic and the melancholic.” Can you say more about why this has engaged you for so long?

Gerry Bergstein:

I grew up with reading comic books, Mad Magazine, Twilight Zone, and science fiction magazines, and one of my favorite shows that I saw more recently as a show of Pulp Fiction covers at the Brooklyn Museum. I think they’re so great.

My parents were very cultured, but they were very shy and isolated almost, so I had a lot of conflicting influences. I like to joke that I was the rebellious son of accountants and dentists. I have all that obsessiveness in me, but I often explode. It’s built into my psychology; even in the 60s, during the height of the student strike, of course, I was absolutely in favor of peace and civil rights, but there was also what I called psychedelic fascism. It was like the left telling you what to do as like the right was telling you what to do–‘meet the new boss, same as the old boss’–or something like that, right?

I’ve always been a skeptic, and I’m not sure why, but I think it’s an interesting place to be. I have two quotes on my website, one from John Lennon and the other from Groucho Marx. Lennon says all you need is love and Marx says whatever it is, I’m against it! (laughs)

LG:

That’s so funny. Great.

Gerry Bergstein:

I also think I can learn stuff like what Ivan Albright has in common with Jackson Pollock, maybe not the deepest connection, but it’s there. What does Chuck Close have in common with the de Kooning, and what makes them different? I think the thing about Chuck Close was that he was temperamentally unsuited to be an abstract painter because he was because of the emotional roller coaster of abstract expressionist painting– I do this as well; if I make one good mark, I suddenly think this is the greatest thing that’s ever happened in art. The emotional; ups and downs were too much for him. He also said that he thought abstraction was not an arena for major breakthroughs at that time.

I also have this idea called chance meetings. I did some collages in the early 2000s; some of them were installations hanging in my studio, with everything attached to string and clothesline. And there were all these photo reproductions of paintings talking to each other. Like maybe The Flintstones and late Leonardo talking to each other. And I find that conglomeration satisfying. And, you know, people criticize it because it was like too much of an art historical joke, and perhaps it was, but maybe it wasn’t completely an art historical joke because for me, it was something real.

LG:

William T Wiley stated in an interview talking about one of his shows,

“It’s like Sir Francis Bacon’s statement, “There’s no thing of excellent beauty that does not have within itself some proportion of strangeness.” So, you know, high and low meet at that point where authenticate expression emerges, I think, and some inspired expression emerges, whether it’s with a razor blade or an old sock, it’s whatever that particular thing. So you could have something there that, the most recent post-modern term is, “Looks like art, so it must be art.”

How do you decide the balance between the disparate elements and the proportion of strangeness?

Gerry Bergstein:

I like that William Wiley statement very much. I think that kind of sums it up for me.

LG:

We talked a little about Greenbergian Modernism art dogma and such, along with the rigid doctrine of both the right and left and other similar closed ideologies that have influenced your art and life. Is there anything more to say about this?

Gerry Bergstein:

The problem with ideologies is that they must be put into practice by people. They all have a degree of truth, but I think that personal ambition is like the “uncertainty” principle” of the art world and most other human worlds. It is never mentioned in ideologies but is a hidden part of their creation. I feel strongly about that, maybe because I was so shy for so long and people around me were expressing themselves with great authority–I was terrified of them. But that’s not true anymore. Now I won’t shut up. (laughs)

LG:

Did underground cartoonists like Robert Crumb or earlier cartoonists like George Herriman ever have much influence on your work?

Gerry Bergstein:

I like R. Crumb. I love that documentary about him. I’m uncomfortable when he beheads women in his work. Still, I think he’s a brilliant draftsman and a kinky guy in an interesting way. George Herriman, I like just because Philip Guston liked him, but I don’t know him very well. I never read psychedelic comics. Instead, I read stuff like Archie and Superman when I was very young. The Hardy Boys, the American dream, Father Knows Best, the American Dream–you’re a good boy. You solved the crime–you’re a good boy. That was a total lie, and that compels me, knowing how we delude ourselves.

LG:

Can you say something about your painting process? I’m curious how much you consciously plan out your paintings or do they take on a life of their own without much planning beforehand?

Gerry Bergstein:

I’ve had many different processes, but I can give you a few of them.

When I was still in school, I was in love with Arshile Gorky, and I loved the sort of eroticism and delicacy of his line and shape. I loved his rigorous compositions, but I couldn’t get it in my own work. And one day, I had this color canvas, and in a fit of pique, I just painted the whole thing black and scraped into it with the back of my paintbrush. I thought, Oh, there’s Gorky’s line. So I fell in love with it. I thought it was the best painting of the 20th century, and I showed it to BarneyRubenstein, and he said, well, it’s very nice, but it looks like Gorky. So I learned that you have to add something. The technique that I’ve probably used the most, and what I’m working on right now, are these black and white pieces where I start out using black gesso and two or three layers of ivory black with a little wax medium. So there’s a little bit of tooth to it; I blot it and let it dry. I then apply zinc white mixed with a little clove oil which keeps it wet for a month. I then use these different tools that I scrape into the picture. I usually have a structure in mind.

Until about three months ago, for about a year, I was doing these orb-like shapes; sometimes, they reminded me almost like a flying saucer, or Earth, or maybe my brain. I would draw in the structure and then randomly, with a lot of agitation, move my arm around within the structure. I would try perspectival and other ways of making things look round. Gradually biomorphic shapes or ruined landscapes parts of it would emerge, and every day I come into the studio and do it some more, and then when that all dried, I would take these little tiny brushes and enhance some of the shapes that I saw. They became quite different.

And in my newer ones, I have collaged photographs of different parts of different paintings, and I print them in slightly different colors from black and white. So the newest ones have a little bit of color in them again. So that’ sgraffito technique affords me the opportunity to rorschach and free-associate and make mistakes.

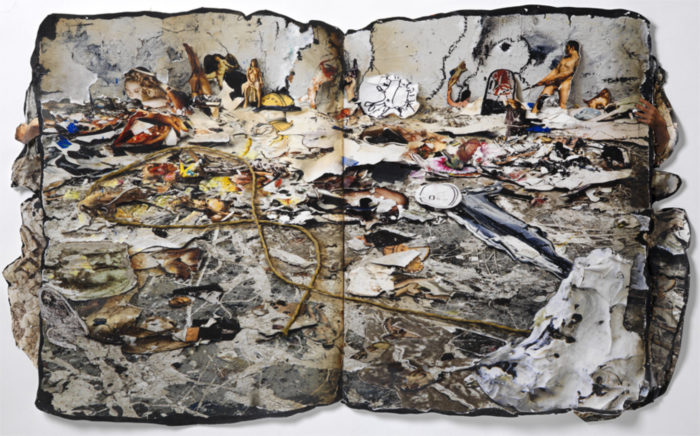

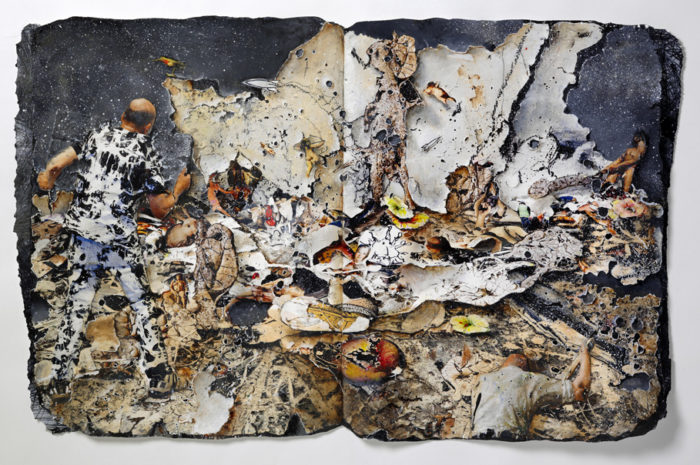

I tried another thing a few years earlier for my show “Theory and Practice” at the Naga Gallery I became seduced by digital photography, for better or worse. It took me about 10 years to do anything I sort of liked. My studio floor is a mess, it’s a painting in itself, and every time I cut out a little figure or historical image that I’d want to try out in a painting. it falls on the floor along with the drips on the floor, and then I decided to pour white house paint on top of all this and cover up some of it, but not all of it. I then would walk around it until I’d find a composition I liked. I then had a friend come in with a 200-megapixel Hasselblad, and he took a picture of it for me. I photographed it and printed it out large, very large on canvas, like five by six feet.

LG:

Did you print that yourself or did you have someone else?

Gerry Bergstein:

Luckily I had access to the Museum School’s printers and their Tech Assistants.

LG:

Wow, that’s great.

Gerry Bergstein:

So I would do that, and then I would take detailed shots of little parts of the floor. So the big shot was the floor meeting the wall. There was graffiti on the wall, and there was stuff on the floor. But then I would take these drips of white house paint that would crack after a while. They would also get distressed after I walked on them after they were dry. They would begin to look like fossilized de Kooning pours. So we take pictures of them and then cut them out and collage them into the painting. One of my favorites sort of looked like a fossilized de Kooning. There too, I would paint into them and see things in the abstract shapes that look like images, but then if they became too much like images-that, they got corny, I might need to scale it back. It was a kind of a juggling act.

I also had a still life period when I met Gail, who is the complete opposite of me. I was deeply in love with her, and she became my muse and led me to make these beautiful still lives of flowers and fruit for three or four years (in the 90s. – I wanted to be very beautiful but also deal with vanitas, the evanescence of all beauty in art and life.

LG:

Those fruit and flower were almost little sculptures made from thick paint, right?

Gerry Bergstein:

Yes, some of them used toy model railroad workers who were constructing fruit out of very thick paint. I love the idea of something being pure paint and image simultaneously. Like how you might see in Thiebaud’s thickly painted picture of Ketchup, Mustard, and Mayonaise.

Sometimes what happens is that I’m doing something for three to five years and I begin to get bored. First, it’s a learning curve, and then after I learned how to do it and do some really good work, It begins to be a little too easy, and I get bored. And so I think the reason I stopped doing this sgraffito for many years was that I got sick of it. However, now, I’m into it again.

In a still earlier phase, I would paint fruit on a canvas, and then I would drip white paint on top of it, then I would paint into the white paint, and gradually, there were so many drips on top of it that they became totally abstract. Eventually, I lost my way, and I went into something else.

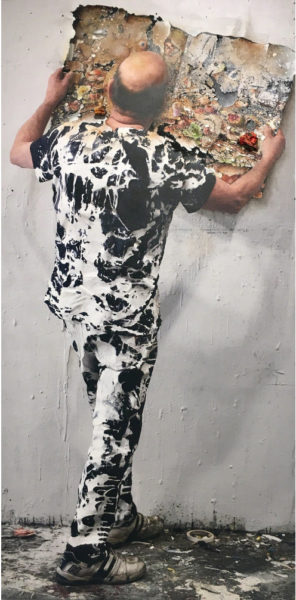

I developed a couple of techniques for a series of figure self-portraits where the head looks like a drawing, but it’s actually a painting. I would take a photograph and then have this white paint on top of black paint and then trace an outline from the photograph; I would then very carefully render the head on the canvas with a pencil. So it looked like a pretty good realist depiction. But then, on the bodies, I would have image illusions of little scraps of paper with all my favorite artists listed or images from artists like Gorky or Vija Celmins to my father’s head, to an anatomical chart part. And so my body became art history or something personal as an artist thing. Randall Diehl, a friend of Gregory Gillespie’s did this great self-portrait with tattoos of different artists all over his body. I like art about art.

LG:

That’s so interesting. I noticed that in a few of your paintings where you include some type of self-portrait, You’re wearing this paint-dripped shirt and pants that look a little like a blend of a de Kooning and a Hubble photo of the stars, making you look like a cosmic house painter. Is that something you made?

Gerry Bergstein:

I made that myself; it’s a t-shirt with black Jeans with acrylic poured on top of it. I wore that outfit of the day opening of that show.

LG:

That’s so funny.

Gerry Bergstein:

Actually, I just wore the shirt I didn’t wear the pants; that would have been too much.

LG:

I’m not sure if Cosmos is the right word, but there seemed to be a motif of the cosmo running through a number of your works. I’ve read that electron microscope imagery of the structure of neural networks in the brain look remarkably similar to astronomical photos that show the larger patterns of millions of galaxies. Your work sometimes seemed to speak to this fascinating comparison on some level.

Gerry Bergstein:

The macro and the micro Yes. Absolutely. Subatomic and deep space. Yes.

LG:

A great idea for a t-shirt!

Gerry Bergstein:

I’m interested in the cosmos because it is so awesome, mysterious, and spiritual. I’m sort of an agnostic, but I believe there’s something that I’ll never understand or even have a clue about; it’s so wonderfully mysterious. And then you look at the Earth, and we have Donald Trump. Certainly not wonderful and mysterious, he’s the complete opposite of that, from the sublime to the ridiculous. I’m interested in that issue too.

LG:

Ugh, please don’t get me started about Trump! I love these new photos coming from the new James Webb Space Telescope. Just so astounding that we now get this new appreciation of where we are in the larger scheme of things and how small and insignificant we are but at the same time so rare and precious.

Gerry Bergstein:

I know, they’re going to be able to maybe get clues of where there might be life. It’s totally amazing.

LG:

I read a quote from John Walker saying something along the lines of ‘…his forms have to have the volume so that they could imply other things, that his paintings need to be imbued with feeling. Otherwise, it’s just design or decoration.’ Would you agree with this and care to comment further? Do you know him?

Gerry Bergstein:

I don’t know him but I admire his work. It’s a fine line. As someone who loves Bouguereau and Fragonard – I might not be the best one to answer about sentimentality.(laughs)` I think there’s a difference between emotion and sentimentality. There is a lot of feeling in Max Beckmann; There’s a lot of feeling in de Kooning. There’s a lot of feeling in Vija Celmins. Strangely enough. It’s inclusive of feeling, intellect, and process in varying proportions or more or less important to different artists. At times an artist like Hyman Bloom gets a little sentimental but it is a sublime sentimentality. So you know, I think it’s borderline, but art would be nothing without feeling, and art would be nothing without somebody’s mind and imagination. Art might also be nothing without individual techniques of people develop. So I think they’re all important.

LG:

I understand you are married to the painter Gail Boyajian who paints incredible panoramic landscapes with birds. I noticed that one of her paintings ( Vanitas, 2015 ) includes the Tower of Babel. And some of your fruit and flower paintings show some affinities with her work. Despite your subjects and styles being so different, there seem to be a few points where they intersect. I’m curious to hear anything you might say about having a painter as a partner.

Gerry Bergstein:

I made those Fruit and Flower paintings for her; We had one in the background in the place where we got married. I first saw Bruegel’s Tower of Babel painting in 1971 on my first trip to Europe, but I loved it so much that I went back later with Gail; there is a whole room of Bruegel’s paintings. We both love Bruegel.

LG:

I find both the story of the Tower of Babel and Bruegel’s painting so compelling – like the bible saying humans need to stay in their lane – don’t evolve with greater ambitions like advances in civilization. To not build our knowledge, medicine, science, and humanity any higher. It shows how insecure this God must be to worry about humans rising above their station.

Gerry Bergstein:

I see it as human ambition taking over from God, and That’s why he destroyed it, and it’s hubris, and it’s the kind of like power-seeking or knowing everything or which we never can do because (goddamn) God made us so we couldn’t do it. (laughs) But I can see your point; I think it’s the opposite side of the same coin. It’s about the folly of ambition and power. But on the other hand, that’s all we have, and I love ambition and power. It’s a double-edged sword.

LG:

Sorry, I interrupted you, please continue talking about your wife.

Gerry Bergstein:

It’s a really interesting relationship. She rarely watches television. She doesn’t know what Mad Magazine was. She doesn’t know the New Wave music I used to listen to. But she’s a total expert on Henry James and George Eliot. So when we first got together, we vowed that I would read Portrait of a Lady, and she was going to watch LA Law. (laughs) So she watched one episode of LA Law, and I read one chapter of Portrait of a Lady, and we’ve been arguing about it ever since. But now we’re starting to come together in the center. I read a great biography of Henry James recently; I was fascinated by it because he was an ambitious insecure guy, just like the rest of us. (laughs) So we have great discussions, and she’s a good critic of certain things in my work, like where something is spatially. So we’re encouraging and helping each other in our work. Since our work is so different, we’re not competitive with each other. She has a different sort of ambition than I do. My ambition is changing as I get older, a little more contemplative. I’m not so anxious.

LG:

As you get older, are you working on a smaller scale?

Gerry Bergstein:

Actually, it’s getting bigger; it’s getting both bigger and smaller.

LG:

The scale of so many of your works is huge. I’m curious; some painters I’ve talked to start to work smaller because they don’t have the storage space or other reasons, but you sell most of your work, so that’s probably not an issue, right?

Gerry Bergstein:

I don’t sell a huge amount of work. I like the people at the Naga Gallery–they are really honest and helpful. But I think some of my newer work is too fragile and large, I don’t know why I like to keep doing it. I guess I’m an idiot. (laughs) Maybe working larger is a reaction to mortality. I’ve had a few health problems; nothing will kill me imminently. But I realize, in a way, I never have before, that this is going to end, and I want to get my last shot in or something. Last year I worked on three super large paintings, the largest of which was 90 by 112 inches. That took over a year, and now I’m returning to somewhat smaller work.

LG:

The population explosion of painters over the past several decades has made the competition to show and sell paintings impossibly stiff, especially in a higher-end market where someone might make enough to live on. Paintings are often valued less for artistic merit and more for saleability or marketing. What opinion can you share about this dynamic?

Gerry Bergstein:

That’s an interesting question because I love to sell work, and I’m always fantasizing about selling work, but if I were more interested in selling, I’d make very different work. So it’s a mixed bag. I do work that is difficult and then complain if no one wants it. (laughs) I do think about it, certainly, but I don’t let it interfere with decision-making in the actual act of painting. It’s a balancing act.

LG:

It seems to me that for some artists, the more they try to make it sellable, the worse it gets. The important thing is to focus on the integrity of the work, which you do.

Gerry Bergstein:

It’s really hard. Putting yourself out in the world. It’s very important. I do it reluctantly, but I do it. However, I do it less as I’m getting older. I’m showing less and getting out in the world. Covid, of course, was bit of a damper. (laughs)

LG:

How much should young painters care about the commercial potential of their artwork? What advice might you offer the younger generation of painters coming up?

Gerry Bergstein:

They should be thinking about making friends with other artists. That’s good for discussion of the work and also good for introductions. I got my start from a friend who introduced me to a dealer and got a show. I probably would have never done that on my own. But you can go too far in either direction. I agree with you. Students need some sort of discussion of what happens right after school and how to survive, how to survive with a day job, and have a goal to work themselves up to. As shy as I was, when my work started getting good, about 1980, and I began to stand behind my work, I didn’t have any problem showing it to people, but before that, I was always a little shaky, and maybe for a good reason. Even now, I don’t often send my work out to dealers very much in other cities. I used to do that. I showed in places other than Boston.

I think young artists need to know that it’s a hard business. They have to be very persistent so that they might luck out and have a show and sell when they’re very young, which comes with its own difficulties. Or they might have to work for several years. I had I’ve had students for whom I write letters of recommendation to get into graduate school every year for ten years, and then finally, they get accepted. I think it takes a long time to learn how to paint. There is one woman I taught; not only did she get into grad school, but now she’s getting these teaching jobs. She’s a great landscape painter, and if she hadn’t worked for eight or nine years without much recognition, It would have been sad because she’s doing terrific work.

If you get discouraged and want to quit, that’s your business. I’ve also had painters who got out of grad school and started showing in galleries a year later and sold their work for a lot of money, and then–just like that–it ends. They can’t figure out what else to do. Whatever you’re doing, you have to be in it for the long haul, be honest with yourself and let the chips fall where they may. The whole thing about the overblown art market, work selling for hundreds of millions of dollars, is obscene. But the other question is if I could sell a painting for a hundred million dollars, I bet I would! (laughs) I still think it’s obscene. Artists deserve to make a living, maybe even a comfortable living, but this commodification stuff, with people, are buying art for the wrong reasons, is awful. The young artist has to navigate commodification as well as being able to navigate socializing and friendships. They have to be assertive and get their work out there and don’t expect it always to work out, to have a thick skin. Applying for grants and the like, it’s a crapshoot. And you know, Maybe if you’re lucky, you’ll get one in 20 tries, so just keep doing it.

LG:

Do you have a show coming up at some point in the near future?

Gerry Bergstein:

Yes, in September 2023 at the Naga Gallery.

LG:

You’ll be showing these new large paintings you mentioned there?

Gerry Bergstein:

I have some small ones to show too. The Gallery Naga is so great; they encourage you to take more risks and not be worried about what people think; they’re very supportive. I’m happy about that.

LG:

From what I know, it’s a brilliant gallery with a wonderfully diverse range of painters.

Gerry Bergstein:

Yes, they do.

LG:

Many galleries are having a hard time in this economy and all. Are they doing ok?

Gerry Bergstein:

Yes, the Naga is healthy because they’re good business people. Since covid, it has complicated things for all the galleries.

LG:

is Arthur Dion still the director?

Gerry Bergstein:

No, Arthur retired. Meg White replaced him. Arthur has become a very serious Buddhist.

LG:

Is Buddhism something that interests you as well? It’s been important for many painters, like Gregory Gillespie

Gerry Bergstein:

Only peripherally. I’ve tried meditation, but I’m so bad at it. David Sipress had a great cartoon, of a man raising his hand in a meditation class saying, “I’m thinking about not thinking, is that correct?” (laughs) And that’s what happens to me when I meditate. I do it once in a while, and it’s helpful if I’m anxious about something. How about you, do you meditate?

LG:

No, however, after lunch, I like to listen to classical music in an almost asleep, dreamlike state for 20 minutes or so. It’s rejuvenating. I don’t think it’s meditating, though, but it works for me.

Do you paint while listening to music?

Gerry Bergstein:

Classical music, yes! I love chamber music. When I started this new series of paintings, I listened exclusively to the chamber music of Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, and Mendelssohn, while I was painting and it was so inspiring. I also love rock music.

LG:

Do you ever worry about the music influencing the painting too much on some level?

Gerry Bergstein:

Yes, I’ve heard that; maybe that’s true. And I used to always until I was until about 1990 I listened to music constantly in the studio. Either classical or new wave, Punk or whatever. And then suddenly I started listening to the news…

LG:

Oh no, that’s pretty sad these days. (laughs)

Gerry Bergstein:

And then now I’m back listening to music. But not quite as much, I have to remind myself. But when I’m doing it, I love it.

LG:

I feel that I want to paint as much as I can. If I spent all my time painting with no music, then I’d never get to listen to music. Life’s hard enough; you might as well enjoy it wherever you can!

Gerry Bergstein:

Exactly. I agree; I love music; I think it’s the highest art form.

LG:

Sometimes I imagine what musician would be most like a certain painter, what musician would I equate them with? Maybe your musical doppelgänger would be Frank Zappa, would that be fair?

Gerry Bergstein:

Absolutely!, We’re in it Only for the Money is one of my all-time favorite albums.

LG:

A funny thing – that album I heard was part of a project that Zappa called No Commerical Potential – yet it was such a huge success. Another example of the importance of being true to your creative self.

Gerry Bergstein:

I also listen to John Coltrane and Charlie Mingus. Sometimes I imagine the blacks in my painting remind me of someone playing the cello, like a Bach Cello Suite or something. So it’s a wide range.

But then, I’ll listen to Little Richard the next day. I want to have Beethoven’s Grosse Fugue, followed by Chuck Berry’s Roll Over Beethoven, played at my funeral.

LG:

That sounds perfect. Let’s hope that won’t be for many, many years in the future.

Overwhelming!!!!! It left be out of breathe And exhausted and wanting to hide away some place in the woods and read it all again very very slowly …. Like upstate NY in Blue Mountain Lake with 12 feet of snow outside so I could absorb it all … for a shy guy Gerry said a lot .. great interview. More people need to read it … maybe I paint tomorrow finally !!! Henry would love to read this and then complain and be critical … and just sit there with Gerry and listen to some ?? Fir an hour or so . Then both would say nothing and leave in silence … special people !!!

I had Gerry as a teacher in the 1980’s, he was my first painting teacher. I can’t remember much but I do remember that he was very encouraging and seem to want everyone to find their own way, which is probably what most good teachers do. Love his paintings, he should be a star!

Great interview, happy to be acquainted w. Mr. Bergstein’s work. I loved all the cross referencing to Gregory Gillespie, whose work I have loved since the 90s.

Your exchange is very meaningful to me. I do not study painting, but now my daughter is studying painting, so I have learned more about painting. Thank you very much!