I’m pleased to share this interview with the wonderful Bay Area California painter Gage Opdenbrouw where he talks at length about his background, process and thoughts on making his landscapes and views of his studio in Oakland, Ca. I would like to thank him for his generosity in responding to my email interview questions.

His website’s general statement is a great introduction for those who may not be familiar with him and include it here:

…painting is a way of drawing close to moments, and an attempt to pay homage to the fleeting beauty of everyday observations. Regardless of the subject, whether a figure or a moment of light in an interior, the sweep of a sky above an industrial neighborhood, the goal is, as Joseph Campbell once put it, “to reveal the radiance that lies hidden just beneath the surface of every day”. I’m hoping to use a brush to create some poetry from mundane materials, and if the paintings resonate with the viewer in the eye, the heart, the gut, then I feel I’ve been successful in sharing some small aspect of my experience.

His list of solo shows includes: John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, CA, 2017 and Luna Rienne Gallery, San Francisco in 2016, and has shown widely in group exhibitions.

Larry Groff: How did you first decide to become a painter?

Gage Opdenbrouw: I always drew a lot, as a teenager I found that I couldn’t paint in a way that equaled my command of drawing. So I found myself frustrated because I was lacking an understanding of the concept of masses. My work was essentially linear, just drawing in color. But at the same time I had some great teachers. I was one of those smart but somewhat maladjusted kids in high school that was always getting in trouble–the type that was capable of getting A’s–but mostly getting detention.

I was in a group show a few years ago that Kyle Staver had several paintings in, and her artist statement recounts someone pulling her aside, a teacher, I think, and saying, ‘I know what’s wrong with you, you’re an artist!’ Her remark really cracked me up because it was a similar experience for me, only I had to figure it out myself.

My last year of high school was at a sort of alternative program at the local city college, where I got to take college level art and philosophy classes. I’d always been a big reader, and had been really drawing a lot and keeping a sketchbook, looking at a lot of art since my early teens. So I think a couple of the teachers that I had at San Jose City College were really big influences in encouraging me to dig deeper. I had several figure drawing and painting classes with an artist named Luis Guiterrez, who, as far as I knew from his classes, was sort of a Franz Kline-like painter. I was shocked to see after knowing him for a couple years that he had done Frederic Remington type cowboy paintings in his youth, very well, at that. But he always encouraged us to work loosely, to collaborate with the material, to draw in ways that were barely within out control. We worked from a model frequently but he encouraged our response to the model to be more intuitive rather than descriptive. I started to see recruiters from art schools in San Francisco and Oakland on campus, I was very receptive…I had both enough experience, and enough encouragement; to dare to think that maybe I could be a painter.

LG:You studied painting at the Academy of Art College in San Francisco? What was that like for you?

GO: It was interesting. Going into it at 18 or 19, what I really wanted was a very traditional education…I think I saw being able to draw what was in front of you as a certain sort of visual literacy…not to say I valued realism especially, but it seemed to me important somehow as a place to start. it still does. Anyway, it was, and still is, a very commercial school. I started as an illustration major, as some sort of nod to practicality. I admired a lot of illustrators, and loved graphic art, especially Goya, Kollwitz, and the like. My taste was dark and dramatic, romantic…Turner and Friedrich were both revelations. At the time illustration was still seen as a viable option, when in a lot of ways it was really beginning dying off from a much healthier period. Anyway, the illustration program was great as a foundation–we drew from life constantly, mostly the figure, clothed, nude, and mostly quick drawings…I had some really great teachers. After a couple years I switched my major to painting, which was a much smaller department–between painting, sculpture, and printmaking majors, there weren’t more than a couple hundred fine art students, and really there was a core of several dozen that was super dedicated. I hung around that group and soaked up as much as could, often with a bruised ego. It was great. We would have 6-hour studio classes, and then draw or paint the figure another 3-4 hours in the evening, be back at it by 9 the next morning. It was immersive, and competitive, and I met a ton of very talented artists I’m still close with today.

On the downside, the education itself was as close to purely technical as it could be, which was great in a lot of ways–but there was, I think, no real intellectual rigor or philosophical discussion as part of painting classes…in some ways that was good, to my mind, that was what drinking beer with my friends was for, and I think we have all found what we need in that respect since, but I’d say that was the big glaring deficiency, but it’s not like it wasn’t obvious going in. I got what I wanted out of it. But it’s just now, 20 years later, that I can stand Sargent, or Sorolla, or Zorn…everyone emulated those guys with the slashy brushstrokes and a little too much cadmium…by the time I was done with school I was painting from memory and imagination primarily, as I was really sick of the idea of a painting having to be this particular kind of photographically derived, brightly colored, modern day impressionism. But I had great teachers, Craig Nelson’s quick studies class taught me SO much that is still a fundamental part of my daily practice…we would do 4-6 paintings a day in that class, usually from life, some as short as 20 minutes. I think we did 20-minute paintings before lunch and 40s in the afternoon. Just building mileage. I learned a ton about economy, paint handling, focus–how to make an observation count in one mark. How much you can do quickly, if you can attain the right level of focus. That’s still important to me–not speed for its own sake, but the keenness of observation that sort of work teaches you.

I had a great anatomy instructor, for several semesters, got to do a lot of sculpture, which really informed my way of seeing and translating forms, I made prints…All in all it was a great education, and it gave me the time and foundation I needed to begin to develop as an artist.

LG: What have been some of your more important influences that have led you to paint the way you do?

GO: Expressive artists who were also great draftsmen heavily influenced me; such as Goya, Kollwitz, and Daumier…their drama and the sense of visual force has had a major impact. German expressionist painters, Munch, etc. were also huge. I was a pretty alienated kid so the sense of social critique, the angst, all clearly spoke to me.

Cezanne, Giacometti, Vuillard, Bonnard, Degas …Morandi…the Bay Area figurative painters have all been important to me. There was a show at Santa Clara University last year, that was really great, it was a juried show of figure paintings, “Honoring the Legacy of David Park”, they had a great panel, including Jennifer Pochinski, and several members of Park’s family. My painting “Garden”, from the series “Garland of Hours”, won a prize, and that was one of the greatest honors I’ve received thus far. It was amazing for one for his daughters to say she thought my painting was lovely and the one her father would have chosen. Fairfield Porter and Matisse have been big for me lately. Edwin Dickinson is another, we have that incredible big The Cello Player painting in the De Young Museum in San Francisco, and that’s a treasure. Andrew Wyeth is a giant for me. I grew up with books of his work, and that 100-year retrospective last year was incredible.

LG: How important is working from observation to your painting process? Would you say you spend more time looking at the motif or the painting?

GO: It’s important, absolutely! It remains a touchstone. But I don’t have any dogmatic feeling about it, and I use photographs and drawings, usually all in some sort of combination. Initially, I tend to spend more time looking at the motif, but overall, yes, looking at the painting dominates. So observation is important as a source for inspiration, rather than a be and end all type of philosophy… and so that’s really just an everyday habit of looking, noticing. In that sense, I think it is all truly from memory, even when we work from life or a photo. Just in looking away from the canvas, and looking back. And I think that’s good. Working from life I find it easy to be overwhelmed by too much information…it’s rich, and amazing, but I need to take some distance from the motif at a certain point, and just develop it as a painting. It should get to a point where it begins to have its own momentum, its own internal logic; that starts to tell me what it wants.

I find sustained painting from life to be a bit overwhelming in the amount of external input…that pressure is good in forming the first session of a painting, but it can often cause me to lose focus in later sessions. So often I will only work from memory or photos or drawings from that point, going back to life only if I’m stumped on something, something where more information is needed, or need a new input to force a more radical change.

LG: What are some of your considerations for deciding on what might make a good painting?

GO: The most important thing is getting a strong feeling for the motif or sharp idea that I am excited to dig into. It’s all dominated by light; the subject matter is incidental in a way and not necessarily my driving concern. Right now I’m most drawn to landscapes and interiors, both focused on color and space. And in certain ways these paintings are formally driven. I’m driven by simple arrangements of shapes of color.

There’s such joy for me in the visual world, such frequent surprise and resonance, that I think being able to put some of that down, just the pleasure of a few simple shapes, a chord of color, a visual rhythm, something very abstract in nature, that drives it as much as anything. But ultimately it’s a matter of being receptive to whatever I may notice, and respond to. I suppose compared to my earlier years, I don’t look for drama–I look for quiet, peace, radiance. The famous Matisse quote about a painting being “…something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.” seemed decadent when I was younger, now I find it refreshing.

I think that quiet art–small, modest with everyday themes–is becoming a radical notion. I read a review of Rackstraw Downes’ most recent show recently that was entitled something like “the radical possibility of seeing what’s in front of you”. I loved that. I want to be radically engaged with the small things of every day life, incidents of light and shadow. I feel pretty strongly that for me, art has a very particular purpose, and that’s to keep us engaged with wonder and joy. Beauty does that. It calls attention to the miracle of our lives. And that joy is what will sustain us through the storms. That probably sounds corny. Art helps me, in a very deep way, to stay connected to what’s important. But there is a Mary Oliver poem that says this much better;

Don’t Hesitate –by Mary Oliver (from ‘Swan’, 2010)

If you suddenly and unexpectedly feel joy,

don’t hesitate. Give in to it. There are plenty

of lives and whole towns destroyed or about

to be. We are not wise, and not very often

kind. And much can never be redeemed.

Still, life has some possibility left. Perhaps this

is its way of fighting back, that sometimes

something happens better than all the riches

or power in the world. It could be anything,

but very likely you notice it in the instant’

when love begins. Anyway, that’s often the

case. Anyway, whatever it is, don’t be afraid

of its plenty. Joy is not made to be a crumb.

LG: Do you make a lot of drawings before starting?

GO: Not usually. Or if I do they do not bear a very literal relationship to final painting, although sometimes I’ll do a thumbnail or two. However, time spent drawing, as a way of getting close to the subject, is never wasted. I love to show students Andrew Wyeth’s drawings, they way he would do sometimes dozens of quick pencil drawings, before doing a tempera. He’d draw a room 20 different ways, and in the painting it would be different yet again, but synthesizing all those impulses, and responses. And all those observations just seep into the intimacy, the empathy with the subject. And that quality, I think is key. For me it’s all about that depth of feeling.

The way I work, the drawing often comes in last, edges are often the last thing I really develop and drop into place. But I do concern myself primarily with drawing in the sense of overall composition, initially. Color is involved but its secondary to clear interactions between the basic masses of the painting in terms of value. So I do try to do a sort of underpainting even if I don’t usually wait to let it dry before proceeding. I find that to keep the spontaneity and responsiveness that I want in my process, I like to leave a lot of conflicts and problems to be solved in the course of the painting. I like pentimenti–evidence of changes–traces of the painter’s thoughts as well as the successive decisions, weighing and considering. That’s one of the things I find so lively about painters like Uglow, or Lopez Garcia, or Ann Gale. They observe their own observations as much as they look at the subject–which I find very interesting.

LG: Do you draw regularly in a sketchbook?

GO: I try to. Just as often as draw, I write, trying to clarify ideas, write down observations that don’t make their way directly into the painting. On my recent trip to Washington I found myself, after sessions painting outside, doing a verbal ‘download’ of ‘sense memories’ from the day, often sounds, smells, etc. Really trying to retain a specific sense of place in my memory. This is helpful in jogging my memory later should I return to the motif. Sometimes I also draw after making several paintings of the same subject, to try to clarify design ideas. These are usually compositional in nature rather than little elements. Drawing in a sketchbook is something that I’d like to be more of my routine. When I can’t make time to paint for three or four hours this helps keep my creative ferment going, a little way to touch the source every day. I would draw even more if I didn’t have another job as well.

LG: Sometimes painters, during the process of simplifying views, develop a personal shorthand for abbreviating forms and colors, which if repeated over time, could risk becoming cliché or look overly stylized. On the other hand, many other painters doing the same thing preserve the integrity of their brush strokes and marks and keep their personality intact along with a freshness that seems unique and specific. Is this something you ever think much about? What advice would you offer to someone wishing to avoid this problem?

GO: Yes! Things can certainly become too mannered, in a bad way. I think mannerism, or a characteristic ‘mode’ of putting down your observations, isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But it is a very fine line. To me, it’s a question of authenticity, and that is all about authenticity to one’s own observation and impulses, it’s nothing to with the notion of ‘realism’ or ‘painting what you see’, as if that were even possible. In painting from observation we condense or compress a gigantic amount of information into a few marks, and so I think it’s foolish to be overly dismissive of any habit that we may have learned that helps us to make that digestible, a place to begin, a way of beginning and organizing.

I think where artists often stray in this respect is when they want to have a ‘look’ or ‘style’. To my way of thinking, your true voice is not a public speaking voice, but your middle of the night voice, the one that cracks with feeling and is a bit embarrassing, the voice that anyone who loves you would recognize just by its tone and cadence. The one that you can’t help. Trying to be original is the most follow-the-herd, highway-to-mediocrity approach you can have. So if you’re out there trying hard to paint like Kanevsky, Uglow, Corot, or Sorolla or whatever it is…it could be a trap. I think what makes it sing is the authenticity of engagement with both the subject and the painting. So if you are seeing something that way, then by all means, chase it.

We are always chasing an abstract ideal, a pictorial concept we are trying to impose on the subject, which comes largely from all the paintings we have ever admired, so to even imagine we can take influence out of it is not realistic to my mind. We’re painters, we work within a tradition, which is to say a set of conventions. But yet, when we are not pushing the envelope, and surprising ourselves, that’s where the bad mannering comes in–a sort of autopilot that is the polar opposite of crisp, clear painterly observation and decision. I see it as about the quality of your attention. If you’re connecting, it will show. If you’re not, that will too.

It’s something along the lines of ‘make a certain mistake often enough and they’ll call it a style’ (some delta blues player, can’t remember now which one), or ‘character is who you are in the dark’. If you are thinking about ‘style’ while you’re painting, someone else might as well be painting.

LG: How important is seeing hand of the artist in a painting?

GO: It’s very important, one of the most poignant concerns. “The snail trail” of human presence that Bacon refers to. I’m more moved by doubt, uncertainty, skepticism than I am by virtuoso performances in that regard. In this regard I prefer Giacometti or Morandi, Vuillard or Manet, over the flashy brushwork of Zorn, Sorolla, Sargent. This speaks to how personal and idiosyncratic each painter’s concept of representation is. There’s an old Chinese proverb about the three things needing to be in balance to create a work of art. The touch. The eye. The heart. All of these things form a painter’s voice.

It’s a language that one has to teach themselves, how to digest and condense what’s in front of you in a way that remains authentic to the experience of looking or the intent. The touch of a painter is everything, how he or she builds forms, accents some and rolls others together into a generative soup…There is something incredibly poignant to me, in the wobbly humility of a handmade object, especially one that somehow conveys a wordless experience across time the way a painting can. Think of what we get from Vermeer’s hand, versus, say, Soutine. Chardin or Rembrandt. What a rich world of possibilities. It’s shocking how much can be done with paint, really, and the diversity of it, technically, given that it is such a primitive medium.

LG: Please tell us something about your life as a painter up in Bay area? Is there a healthy community of painters there who you connect with?

GO: Yes! Definitely. Since I went to school here, I know tons of artists, both from those days and all the time since. There are so many who have moved away, and I will be joining them soon enough, despite there being community it’s a tough place to be an artist, for a number of reasons, but it’s also a place where artists like to live. So yeah, in fact I probably don’t know enough civilians, really, on balance.

Honestly though I haven’t shown much here for a long time, and I think that’s true of many artists here: there’s just not the buyer support, at least not for relatively traditional painting. And what little support there was was has dropped off and changed a lot in the last 15 years or so. Not trying to be sour grapes but I think it’s been a real change. I think space is just so painfully expensive that it’s difficult for people to sustain their creative lives here. But in general, the Bay area still has a very good creative scene overall, tons of visual art, music, lots of it very adventurous, to say the least.

My artist friends here are doing very different sorts of work, and that diversity is very inspiring. However, in terms of work that is closer to my own I feel more connected with artists outside this area. I do have a core group of painter friends here who I try to talk shop with as often as possible-–trading studio visits with other painters is great and I like to do this as much as I can. Naturally, I love to go to galleries and museums but visiting painters in their studios: those conversations are what I return to in thinking about my work.

LG: How important is solitude when you paint?

GO: Solitude is definitely one of my major requirements in life, and at 41 I don’t have any trouble getting it. There’s that lovely line in ‘letters to a young poet’ where Rilke says something to the effect of ‘your life will become a dusky solitude past which the noise of others will pass without notice’. To some people that sounds terrifying, I imagine, for me it sounds absolutely lovely. I like to be alone. I need it. There’s just so much noise, in it’s presence do we even think our own thoughts, feel our own lives deeply enough?

Solitude in nature is what really feeds it all, on a deeper level, for me, and that means hiking, camping, etc, frequently. The silence, the vastness, the sense of scale, including the scale of time evident in the land, in the trees and plants…all of that really feeds and grounds me. Most often I don’t paint, as I am making an effort to drink it all in as deeply as I can–I read something where Andrew Wyeth said something along the lines of ‘I get a lot of painting done, when I’m not painting’, and I know just what he meant. I think it’s pretty hard to have that kind of solitude in the presence of another person. But that doesn’t mean I always need those kinds of conditions to paint, just that it’s important I get that kind of contemplative time steadily.

There are so many kinds of solitude; maybe it would be useful to define what we are talking about. Certainly the solitude of working alone in the studio or out in the landscape is critical for me. It is the foundation of everything. The wordless connection with my life, our lives, this world, revealed so poignantly through my visual world. So it is a meditation that I need to spend time with.

I work first thing in the morning, on days when I get to paint. Sometimes it is just sitting in the studio, this morning it is writing these answers, but most often I paint something quickly with a cup of coffee in my hand. I work almost exclusively by natural light, as I have a studio with wonderful windows and soft even natural light. So there’s the solitude of living in an undesirable area that no one visits, surrounded by traffic jams (I’m in an industrial area near the freeway, train tracks, etc.), where there is no temptation to go out and about.

Additionally my space is beautiful, a big live/work loft in a converted factory, with beautiful light, high ceilings, on one side you can see out over, and on a clear day, across the bay, and on the other there’s a great view over East Oakland toward the hills which reminds me a lot of Mt. St. Victoire…I look at it a lot and haven’t really begun to paint those landscapes nearly as much as I intend to. There are just so many paintings competing to get started…So that requires time, and buying time here takes a lot of effort.

Studio work, one’s path as an artist, has so much solitude built into it. I think it’s part of why friendships with other painters is so important: only we know how to support one another in all the difficult places that a life dedicated to painting takes you. My old friend Miya Ando calls artists ‘civilians’. I think it’s an apt analogy, in the sense that a lot of folks ‘just don’t get it’. Artists have to go to a lot of relatively dark interior places to be able to make their work, and it’s taxing. There are complexes and systems of doubt that dedicated artists live with that a civilian can’t even see, much less feel the weight of. So you really need your community to lean on–not just for aesthetic or artistic inspirations but for support with all of that.

Haruki Murakami’s book, “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running: A Memoir” is a beautiful look into taking care of one’s self as an artist. After he started writing seriously he quit drinking and smoking and took up long distance running, knowing that his art would lead him to interior places that he needed to train for, to have the requisite strength to live that life. Of course, many folks take the opposite direction, but was inspiring, even if unrealistic for me. I mean that I absolutely hate running. But I love hiking, biking, backpacking, yoga, etc. Exercise and meditation and yoga are all key to keeping my strength up. I did quit smoking, finally, and it’s been a couple years. So that’s good. It’s a great book.

LG: You recently were given a residency at the Mineral School in Washington near Mineral Lake and Mt. Rainier. What was that like for you?

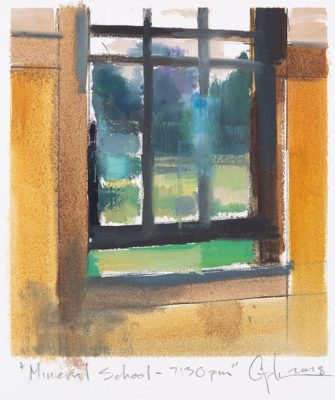

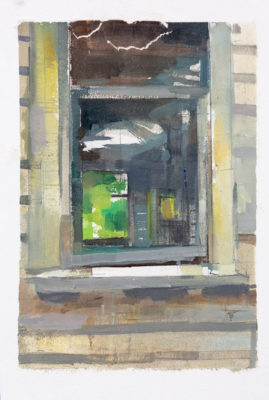

GO: Mineral School was really fantastic. It’s a small, quiet town nestled into the mountains ringing the base of Mt. Rainier, an inspiring place to work. The residency is small, consisting of just 4 residents and a few staff and is housed in a beautiful school from 1946. It’s primarily for writers, and residents stay in classrooms with huge windows and chalkboards on two walls.

I’ve always have been fascinated by the natural world and grew up hiking and camping. My studio and home is in a converted factory loft in East Oakland, a light industrial area between the freeway and the more residential sprawl. It’s empty lots, cab-yards, warehouses, abandoned cars, and homeless camps. So I have this big space with beautiful light, but it’s in a super desolate area. And there’s a lot of congestion, frustration, noise, confusion, illegal dumping, etc. There are other things I like about Oakland but my neighborhood is pretty raw. My studio is a beautifully sunlit sanctuary, though I do end up living like a hermit. However, I suppose that’s how be anywhere. But it has a particular gritty character here.

So just being in the mountains for a couple weeks was wonderful, and the other residents were all very focused, brought big projects with them. Being in this environment where painting was my priority; thinking, reading and writing about painting or just reflecting on life in general, and feeling that I was being supported was a great feeling.

The first week there was a lot of smoke from the many fires but eventually it let up and I got outside to painted …the colors are so weird and queasy with heavy smoke, it’s an interesting challenge to paint. But there were days it was so bad I had to stay inside. Ominous.

This is an incredible landscape, with all the volcanic forms of the cascades, these dramatic knife-edge shapes that loom in and out of the fog and the smoke. It was incredible the scale of what could be revealed once the fog and smoke cleared. I’d been there 4 days before I saw the mountain…I knew it would be huge, but I was still utterly floored when I finally saw it.

There was also a whole other component to my trip: I’d been wanting to work with the image of a partially burned house. It’s an evocative subject and one that seemed to me to speak powerfully of loss…I’ve lost a few close family members in the last couple years and have been feeling a certain pressure to put some of that grief into paint. My Aunt, who I was very close to all my life, died, in fact, after a long illness, while I was on this trip. Anyway, I looked out the window on my first day at Mineral School, and there was a 2 story house, partially burned, standing on the lot next door. I went over and had a look at it, and it was almost tailor made for what I had been thinking of, if I’d had a chance to burn a house just to use it as a setup for a painting, I couldn’t have done a better job. Parts of the facade and a couple rooms on the first floor were still intact, and the charred wood, the plants growing in the windows, the soil and broken pottery, plants growing out of the floor, peeling paint…it was all enormously inspiring, I felt it spoke so eloquently of loss, and time, and our efforts to hold on to all that we love. There was a plum tree in the yard there, and several outbuildings, and more than once when I would go over there, deer would scatter from the abandoned shacks where they’d been feasting on the plums. I even found burnt pages from books that had been in the house. I was told it had burned about 6 years ago, and slumped and slouched a little more with every winter. So I sketched there a great deal but felt oil paintings of this subject needed to be bigger in format, so I just drew and made a few small studies with paint. This has become one of several bodies of work I’m involved with in the studio at present.

LG: What would you say is the most important thing you want to get across to your students attending your workshops?

GO: That making starts is infinitely more important than worrying about ‘finishing’, whatever that is. That great Hawthorne quote about ‘know when you’re licked…’

The need for engagement with your subject, to connect with your reasons for painting, is paramount. To quote Mary Oliver one more time, “Attention is the beginning of devotion”. Painting can be a devotional activity, if practiced with love. So look at it as spending time with what you find beautiful.

LG: How optimistic are you about the future of painting?

GO: Well, I’m very optimistic about the future of painting. I really think it’s very vital at the moment, from what I can tell, there are a ton of painters, and there’s a great plurality of sorts of painting happening, so I think that’s really exciting even if a lot of it doesn’t grab me personally–there’s still plenty that does and that’s what matters. I think it remains a vital and unique form of human endeavor and communication, a pre-verbal or non-verbal way to share experience, to reflect upon the world as well as ourselves. I think that paintings that are slow, quiet, modest in its aims, and focused on human experience…that to me is soul food. It’s not the only kind of painting I enjoy but it’s what I’m most interested in pursuing.

To me this feels like an antidote, a tonic, to our times that move at breakneck speeds, has the attention span of a goldfish, and is increasingly dehumanized and unexamined.

LG: Anything coming up for you in terms of shows or workshops?

GO: My priority is to show more widely, and I’m planning, in the next couple years, some 2, 3 and 4 person shows with painters I admire. That’s more exciting to me than solo shows at the moment. I’ll be teaching several workshops in 2019.

You might have heard about the January 2018 Stanek Gallery show in Philadelphia, Disrupted Realism. John Seed, who was one of the critical players in putting that together, is finishing up a Disrupted Realism book that will be out in 6 months or so, from Schiffer publishing. There will be 38 artists included, and I’m really honored and humbled to be one of them. Lastly, I’ll be doing a solo show entitled “Garland of Hours” at Shasta College in Redding California, in March of 2019, and i’ll be giving a lecture and a workshop along with it. It’s a nice change of pace from commercial galleries

Wonderful interview. Esp like his comments about solitude and the needed supports for an artist; running, yoga etc. Also, his optimism about the future of painting. I’d like to meet him. J.

Thank you for this interview and all the others you provide, Larry. Always inspiring. And today I am especially enjoying the reminiscences of having lived in East Oakland, perhaps even in the same studio complex as Gage. Gage, thanks for your thoughtful and thorough answers to Larry’s questions. Your thoughts are food for this artist’s soul regarding notes on the important of solitude and contemplation, the respect for beauty and its radiance; all of which I think our culture could benefit from.

Thank you Susan! I’m glad you enjoyed it! I’m so curious to know where you lived! I’m in the Oakland Cannery, near the coliseum.

What a great interview, thanks for sharing so much

HI Gage,

I fell in love with your work and especially with Oakland Studio 2, Joel Drawing, oil on panel, 18×24 inches, 2015 and also with Good Grief (30.07.2021)

is it possible to buy them ?

many thanks for taking the time of a reply.

best regards,

Christine