I’ve been following Francis Sills‘ brilliant paintings of landscapes, interiors and still lifes since I first started my Painting Perceptions site back in 2008. I’ve long admired his drive and commitment to observational painting as well as his many career successes. His paintings continue to advance in complexity and visual surprise with his dynamic approaches to drawing with color.

I had the pleasure of meeting him years ago, both where I live in San Diego as well as his home in Charleston, South Carolina during a trip I made there to visit family. Recently we decided to do an email interview that would be posted during his solo exhibition at the Gibbes Museum in Charleston, South Carolina. Sills is represented by the Horton Hayes Fine Art in Charleston, The Kenise Barnes Fine Art, Kent, CT and the Sugarlift gallery in NYC, NY.

Additionally, Sills is an adjunct professor in the Studio Art department at the College of Charleston where he teaches painting and drawing.

Larry Groff: What were your early years like and what made you decide to become a painter?

Francis Sills I grew up in suburban New Jersey about 30 miles west of NYC. I was a creative kid, always making things and I’ve been drawing since I could pick up a pencil. Art always came easy for me, or rather, expressing myself through pictures is probably just how my mind works. In grade school, I was the kid who was always drawing when I should have been reading, writing or working on a math problem. At home, I would make things out of cardboard, build dioramas, set up my toys and draw or photograph them. I went through a stage when I was really into special effects and make-up and took lessons in that. I started fly fishing in middle school and would tie my own flies. I also played the electric bass in high school and college, so doing some kind of art was always in my life. My high school art teacher, Patricia Gatens, was really encouraging and gave me challenging projects to work on and helped to cultivate my visual skills. When it came time to decide what to do for college, I knew it would be something with art, so I decided on a school that had a good art program, good facilities and was part of a larger university campus.

LG: You studied with Jerome Witkin in your undergraduate study at Syracuse University – what was that like for you?

Francis Sills It was a great experience. I had initially thought I would study illustration, but I didn’t really have to make that decision until sophomore year since SU’s art program had a foundation year as a freshman. Those foundation classes included drawing, 2D design, sculpture, an Art history class, and probably some kind of art theory elective. So in my second year, I was taking a combination of illustration classes, figure drawing and also began oil painting. The illustration program was really good, but I found a lot of the work tedious and repetitive of what I learned in high school. Gradually, I became more interested in the practice of painting and figure drawing, which was probably a combination of having Jerome as a teacher and also seeing the large Lucien Freud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of art in 1993-94. After seeing that show multiple times, I decided to switch my major to painting…it really rocked my world.

Jerome was always very generous with me. I recently found a few old sketchbooks from college that had some notes that he wrote to me, which were very encouraging and kind. Jerome was always talking about making work because you had to, that it was somehow your destiny to get these things out of your head and into the world, to go ‘all in’ with what you were trying to paint. He is a storyteller, in his paintings and in his teaching methods, so a lot of the time in class it was him talking about specific artworks or some events in his life that he was trying to paint. It was amazing to watch him draw too. Sometimes that was through a demo in front of the class, or he would just take your pencil or charcoal stick and draw in the margin of your paper, either some structure or form that you should be seeing. On a few occasions, he would just draw the model alongside us during class. It was very inspiring to watch someone with 50+ years of experience make a drawing. I took a semester-long anatomy class with him where we learned the mechanics of the human form, the bones, the muscles and the names of everything. A few of those classes were spent at the downtown hospital in Syracuse in the morgue where he performed autopsies in front of us and then he had us draw from the cadavers. As you can imagine, it was really intense and over the top and nothing less than what you would expect from Jerome. I went to his studio a few times and his house for lunch once. Looking back on it now, I realize that he was being very generous with his time, not just for me, but for most of his students. He’s always been so dedicated to his art; he lives and breathes it, and it was just really inspiring to witness that at such an early stage in my art practice. He showed me the seriousness of the craft and mindset of a professional artist.

LG: Would you say his teaching was influential to what you’re doing now?

Francis Sills I think that he emphasized really knowing what you were trying to paint, not only in a visual way but also all you can about it. His work is about all these weighty historical subjects and events and although I don’t paint that subject matter, he was always trying to get as much information about the subject of his paintings, whether that was from books, the news, film, etc. He always emphasized using your eyes to figure things out first, so that meant drawing from observation. He isn’t a purist in the sense that he works solely in front of the motif or just by perception, but he talked about how the eye was so much more complex than a camera, and that by only using photo reference to paint from you are really limiting your possibilities. I’m not really in touch with him currently, but I saw him a few times after I graduated from SU in 1996. He wrote me a very positive referral letter to get into graduate school along with my other teachers at Syracuse who were formidable, such as Gary Trento and Michael Sickler. I got a really good education at Syracuse and I am grateful I was there at that time and place.

LG: Can you tell us an interesting story about what graduate school was like for you?

Francis Sills I took 3 years off between undergraduate and graduate school. I was living in Brooklyn and I knew I wanted to stay in NYC, so when I got into Parson’s that sealed it for me. I had been painting the whole time, making work in the figurative tradition, still influenced a lot by Jerome and Lucian Freud. Parsons had a really small graduate program, about 15 students per year and an amazing roster of visiting artists. Regina Granne was in charge of the program at that time, along with Glenn Goldberg and Roger Shepard. Looking back, I had so many amazing interactions with the visiting faculty: Amy Sillman, Louise Fishman, David Humphrey, Eric Fischl, Susanna Heller, Richard Tuttle, Joan Snyder all came through the studios. My work in graduate school was all over the place though. I didn’t really know what I wanted to paint anymore. I had gotten in with this figurative work in my portfolio, and I remember having a conversation with Regina (who was also a figurative painter) that I can expect a lot of pushback from this type of work here. I was being exposed to all these different practices and working methods, as well as, seeing what was going on in the contemporary art world in New York at the time. There was a lot of installation art and process-oriented work, and I felt compelled to distance myself from this realist or perceptual tradition that I had come from. It wasn’t cool or relevant and I was young and impressionable and didn’t really know myself or what I wanted. A few things stuck out to me, one was Regina telling me that what the artist is really interested in, what your “real subject matter” is, is what you do in your sketchbook, that place where you can do what you want and not have anyone judge you or where you have to “prove” anything. So after I graduated from Parson’s I looked back in my sketchbooks and I saw all these drawings I was doing of trees, in either Prospect Park or the Brooklyn Botanic garden, and I felt like a fraud or a coward for not making them my real subject matter. Another time I remember having a critique with Richard Tuttle and he was talking about the work I was doing where I began to return to drawing from observation. I was setting up these installations in my studio based on photocopies and drawings that I would pin and tape to my studio walls. I would then draw from these as a way to generate new work. I felt like I was starting to synthesize all that I had been doing and seeing, and it began to solidify and feel right because I was drawing from perception again. Richard noticed this and told me that I had a natural facility for drawing and described me as someone who has “a strong illustrative shorthand for mark making” that I was trying to suppress. He encouraged me to take advantage of my strengths and that I shouldn’t try to hide it or de-skill myself. This advice couldn’t have come from an artist more on the opposite end of the spectrum from me artistically. I felt like it gave me license to go back to working from observation, and trust in that way of working. It took me a while to unpack all that I was exposed to in graduate school and what I was making. That’s also where I met my wife, who is also a painter, so I always say that the best thing I got out of graduate school was her.

LG: After you left Parsons graduate school in 2001 did you want to teach? Was it easy to sustain your painting practice?

Francis Sills Yes, my initial decision to go to graduate school was to get my MFA so I could teach on the college level. I spent a few summers after Parsons teaching pre-college classes to high school students. I was a bit disillusioned with academia honestly; I got the vibe that it was pretty competitive and I saw some bitterness on the part of some of the faculty members. I had this background as a decorative painter, which is what my jobs were between undergrad and grad school, so I fell back into that. I worked in the interior design world, doing murals, faux finishes, plaster walls, gilding and things like that in residential and commercial settings. For a period of time, I co-owned a decorative painting company and had joined the decorators union. It was tough work at times, but rewarding in the sense that I was using my hands and working with other artists who had similar interests. But it was hard to continue with my studio practice the way I wanted to. I had started a family too so there began to be real-life pressures and responsibilities and a lot of juggling of time. My wife and I had a studio in Brooklyn and I would basically work on my paintings any chance I got. At night or on weekends or whenever I could, I painted. I was frustrated honestly and it ultimately lead me and my family to leave NYC after 15 years so my wife and I could focus on our art.

LG: What lead you to move to South Carolina?

Francis Sills Well like I said, living in NYC got to be tough. Working full time, raising a family trying to maintain a studio practice. My heart was in the paintings but it got to be where I wasn’t making enough space for it. My wife had wanted to leave New York a number of years before we finally did, but I was holding out. I still wanted to make it work but I remember hitting a wall the summer before we finally left. I had been working on this large mural commission with a decorative painting company and commuting out to Bayonne NJ every day to climb scaffolding all day in the summer heat. I was working with a few other artists, all pretty jaded and bitter and a little bit older than me. I suddenly saw myself in 15 years in the same spot, doing the same thing, and finally said something has to give. My sister had moved to Charleston a few years prior and she said we should come down to visit, that we would really like it and it was a great place to live. We visited 2 or 3 times and decided to sell our house in Brooklyn and relocate. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do because both my wife and I had lived in NY for 15 years; we started a family there, had many friends and for the most part, were pretty happy and well off.

LG: How has being a painter in Charleston been for you?

Francis Sills It’s been really good. The art community is really welcoming and positive, and small enough that you get to know everyone. I got plugged in pretty quickly and began trying out new subject matter. Before the move, I had been mostly painting industrial landscapes around the Gowanus Canal where my studio was. It was gritty and raw and I was really into Rackstraw Downes’ work. I definitely had to switch gears when I moved here. The light is totally different, the landscape and the colors are totally different. It felt exciting, but also a bit scary like I had landed on another planet or something. There were a few times when we felt like we had made the wrong decision to move. It’s a great place to be a landscape painter though because of the nice weather and easy quality of life. We miss NYC but usually go back once or twice a year to see friends, museums and galleries.

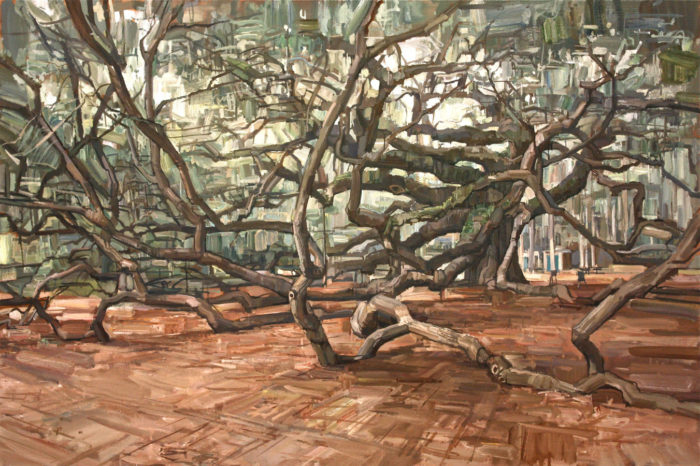

LG: You seem to enjoy painting enormously complex tangles of branches, vegetation and pointy angular things. What attracts you to such a difficult subject?

Francis Sills I guess it’s the complexity that I’m attracted to, with the inherent energy and dynamism of the forms. When I first moved here, I started doing drawings of the live oak trees, which are native to the area. There is a famous one on John’s Island called the Angel Oak, which is this massive live oak tree tucked away in the woods and they say it is possibly 1500 years old. So I saw that my first summer here and it quickly became my muse. I’ve done a number of paintings and drawings of it over the years and working from those forms is like trying to untangle a giant visual knot. The branching of the tree limbs offers me endless possibilities to discover and explore an exciting interplay of positive and negative spaces. Anytime I get stuck with what to paint I usually just go back to drawing trees just like I did in graduate school.

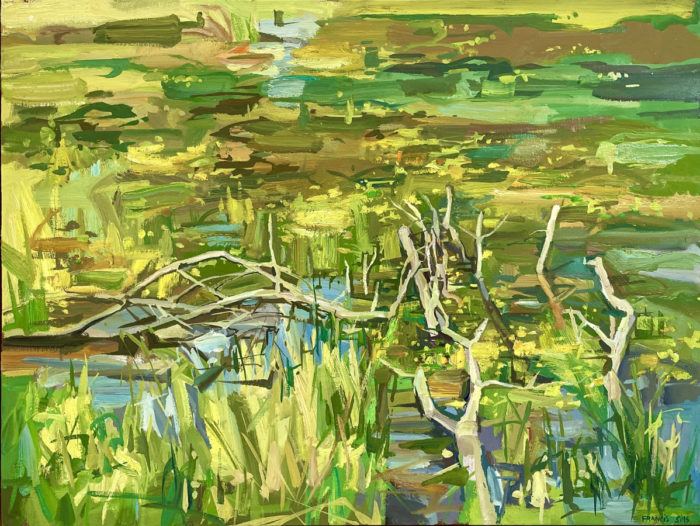

LG: You’ve painted a number of Tupelo and Cypress swamps, even being an artist in residence at one of these state parks outside of Charleston. You avoid nostalgic treatments of the hanging Spanish moss and such and instead seem to go after the more abstract qualities such as the patterns and rhythms of the cypress knees and reflections. The dark swamp water in particular I imagine would be a challenge to paint. Not to mention the logistics of setting up your easel in between the tourists, gators and mosquitos! Can you tell us something more about what that was like for you?

Francis Sills Yeah, I did a series of swamp paintings around 2016-2017. I can’t remember what attracted me to these spots initially; I’m sure it was the remoteness of them and all of those formal qualities you mentioned: the colors, shapes, and patterns. For me, painting these was almost the exact opposite experience of painting in Brooklyn. The colors were something that certainly interested me, as well as the forms of the cypress “knees” as they poked out of the water. While I was researching these areas, I was told about this phenomenon that occurs around January or February, when the sun hits the water at just the right angle and produces a rainbow effect on the surface of the water. It has something to do with how the tannins in the wood leech out into the black water, and given the right conditions and angle of the sun, the surface of the water acts as a prism and you get basically what appears to be a gigantic rainbow of colors on the water’s surface. I saw it a few times and it was quite magical. I found about 3 or 4 black water swamps that were within an hour’s driving distance from my house, so after my kids went to school, I would drive out, get set up by around 9 am and paint until about 2 pm, straight through. I usually had multiple canvases going at the same time so I could switch spots and work on different paintings at different times. It was quite beautiful actually as it was mostly me alone in the woods with the sounds of nature. There were a lot of birding people who I would see at the different locations so it was kind of funny that we were on the same circuit, each of us doing our own thing out in the middle of nowhere. The bugs and heat were definitely something to reckon with, as was the long commute and setting everything up. I saw a few small alligators but nothing too close or menacing; they tend to keep their distance from people. My requirement for the location was that it had to have an elevated boardwalk or platform to paint from, which most had.

LG: What can you tell us about your process? Anything special about your painting technique? What paints do you put out on your palette? Anything note-worthy about how you approach to painting outside?

Francis Sills Over the years, I have developed a pretty compact portable system to paint en plein air. A French easel, a small umbrella, a laundry cart to carry everything (that also turns into a table), and a backpack for my other stuff. I usually tone the canvases I work on a dark brown (raw and burnt umber) thinned with turpentine and I let it totally dry before I paint on it. Usually, I don’t plan things out too much. I used to do preparatory drawings first and square them up in my studio before I went back out to paint. Now I usually just start by blocking in the big shapes with some of those 2-3” disposable chip brushes you get at the hardware store, keeping it real loose and playful in the beginning. I’m just trying to capture the light and color shapes and map out the big forms. Then I’ll go back into that with thinner liner brushes and draw more of the structural elements, similar to the way I would approach things if I was drawing with a charcoal stick or a pencil. As far as color and the paint, I lay out all my colors at once so I have them all there in front of me at my disposal. My color palette hasn’t changed too much over the years, although recently I’ve been adding a few new colors. I started using Veronese green last summer and I just love it. I also needed a cadmium orange a few years ago when I was doing some interiors of my house because we have so much pine molding and I couldn’t get the luminosity I needed by mixing an orange. So it’s about a dozen colors and white, mostly chromatic pigments and some earth tones, with a traditional painting medium of distilled turps, stand oil, damar varnish and a bit of copal. The mosquitos can be pretty bad, unfortunately, so I usually douse myself with insect repellant and sunscreen and make sure I drink plenty of water. From July 4th to Labor Day can be brutally hot and January-February can be a bit rainy, but other than that I’ve got a pretty long season to paint outside.

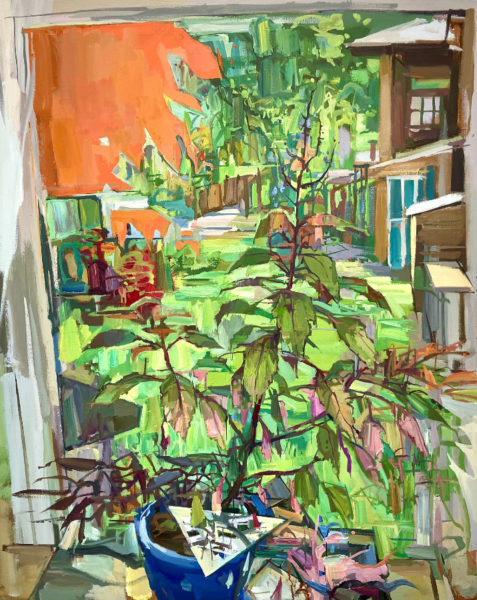

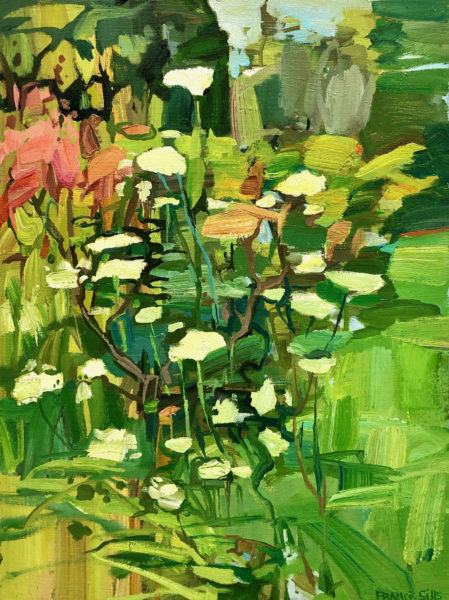

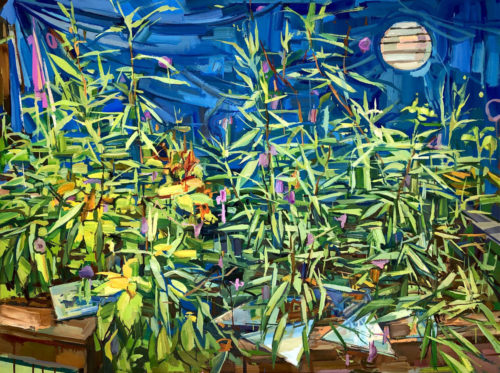

LG: I understand you’ve more recently been painting closer to home – either in your studio or in your garden. I remember visiting your new home and garden a few years back and thinking it would be such a wonderful subject to paint. Are you involved with the gardening along with your wife? Would setting up something like what Monet did with his garden interest you? Maybe a small pond with tupelo and cypress bonsai (is there such a thing?)

Francis Sills Yes, the past couple of years I’ve mostly been painting on my property in our backyard garden. My wife has her studio in the back room of our house, which I think was what I was working in when you visited. About 4 years ago I built a small separate studio outside on our property for myself. So a lot of the time I’ll set up outside with my larger easel, rolling palette table, and an umbrella and just leave everything out there for the duration of the painting. I’ll cover everything each night with a large tarp in case it rains, and this way I can just jump right back into painting each day. This has been especially more important over the past 2 years due to the pandemic when my family and I were existing in this self-contained little world of our house and backyard. I’ve also been working on a larger scale recently so the idea of traveling and transporting all my gear again seems harder to do. Our yard was literally a blank slate when we moved in, and my wife and I have gradually filled in the yard with plantings and trees over the past ten years we’ve been here. She has always had a green thumb and been interested in plants and flowers, and I was always just the laborer, digging holes and such, but I’ve gradually started to educate myself about the plants and am continually finding inspiration from them for paintings and drawings. It’s been a labor of love and I try planting different things just to see what works. Sometimes they die or don’t get enough light but I’ve figured out what grows well through trial and error. The growing season is really long here, and usually, its rare to get a frost, so things stay in bloom and alive most of the year. I view the yard the same way I see a blank canvas and I will go to the garden store in the early Spring and think of picking things out the way I would pick out colors for a painting. So I’m growing this stuff and painting it all in tandem and see the whole process as unified. And yes, something like Monet had is definitely a huge inspiration. I wish I had enough room for a water element; I might have to do with just a small fountain. We just had two large trees removed because of rot and it’s amazing how it has completely altered the light and space of the yard. So now there are these 2 big voids which I’m trying to figure out what to do with and what would grow well there and that feels exciting to me too, just as much as working on a painting.

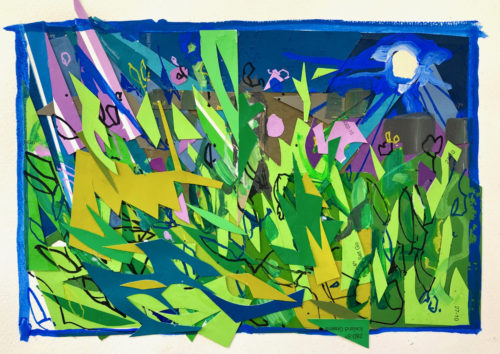

LG: I love the collages I see you’ve been doing recently. They are quite different from much of your other current work but this is something you did many years ago right?

Francis Sills Right, I did a lot of collage work while I was in graduate school at Parsons. That work seemed exciting and fresh…perhaps because collage seems less precious and more ‘playful’ to make. I was investigating things and not having pre-set notions about what was going to come of it, or degrees of finish and all those other things that come with making a painting. It was more of a way for me to improvise, or play within a set of given elements or parameters. I think that is why I like jazz so much for those same characteristics: layering, reacting, and not taking things so seriously. Keeping the process loose and flowing. I got back into it again by starting to cut up some oil on paper paintings I had done from observation. They didn’t work for some reason the way they were, so I started to cut them up and reconfigure them, looking for new shapes and forms. I was also collecting paint chips, the kind you get at the hardware store which are color swatches and using them in the collages and putting them into some still life setups. I was in the decorative painting industry for a long time, so it was always part of that studio environment. I actually worked for a while mixing paint colors for a high-end wallpaper company after college, slowly mixing large batches of paint to master color swatches.

LG: Do you see this a separate area to explore or does it relate to your observational work in some less obvious manner?

Francis Sills It is somewhat separate, in that I tend to deviate from the observed color more. I push the color interpretations to the extreme and don’t feel like I have to be as true to what I’m seeing. Sometimes I’m actually looking at things in front of me though, or I will use photographs as a starting point, or more recently I’ve begun using them more as designs from imagination which I then go on to make larger oil paintings from. A few times I’ve actually just thought of certain color combinations and put them down in collage form as basic shapes in relation to each other, similar to a color notation or color chord and then set something up later as a still life or arranged things in my garden that mimic that. More recently I’ve been using collage solely from memory or imagination rather than observing something “out there” in the world.

LG: Since you clearly enjoy the collage work which presumably isn’t observation-based. What might hold you back from making oil paintings that weren’t from observation?

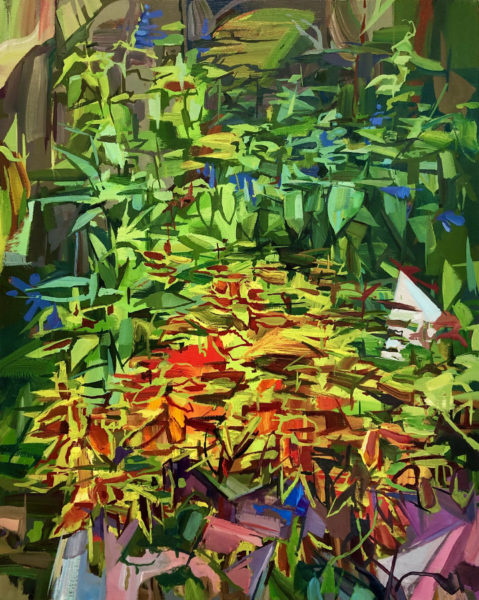

Francis Sills I don’t know. I tend to lose my way without something to observe or give me a starting point to work from. I find that something exciting always occurs while working from observation that I wouldn’t have been able to think of otherwise. It’s not so much that I need to always reproduce what I see in front of me, but it’s more like with the garden paintings there are these two simultaneous events happening. There is this stuff growing and living in front of me, changing with the light and wind and the elements and then there is this image of it that I’m trying to make, pushing and layering paint on this rectangle next to it. Sometimes they cross over into each other and overlap, and the more the painting proceeds, the more these two things weave together. It’s like I want the paintings to grow in the same way the plants grow in the garden, with the same kind of logic and unpredictability. A few years ago I was working on this large painting outside in the garden, and it was pretty far along and almost done. At one point, this gigantic moth emerges out of the plants and starts hovering around the flowers I was trying to paint. It was looking for pollen I think and darting in and out of the flowers and then came over to my painting and just started diving into it, bouncing off the surface of the painting at the same flowers it had been hovering over before, but now it’s trying to get the pollen out of the ‘painted’ flowers. I just stood there watching this whole thing for a few minutes in awe. The moth flew away with some of the paint on it while the painting had preserved the movement of this moth which had disrupted some of the wet paint. It was such a beautiful moment, and not because I thought I had just done some kind of trompe l’oeil trick on the moth, but that there was this overlapping of worlds that had occurred. Like the moth existed for this brief moment in time and chose to visit this painting that was being made and everything just coalesced in front of me and all was in harmony for an instant.

LG: The marks in your paintings lend an expressive element as well as lead the eye through the painting. Your color seems to provide a framework for the drawing more than the drawing being a scaffold for the painted form.

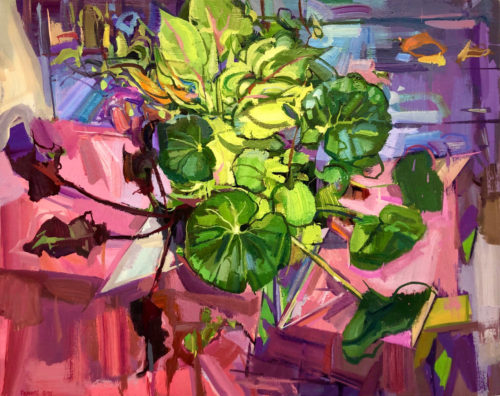

Francis Sills My initial impulse to paint the flowers came from trying to push the colors in my paintings more, to push the saturation and hues out of my comfort zone. All those swamp and tree paintings that I had been doing were so muted and grayed out, so it was a conscious decision to try to paint something more colorful. It was also around this time that I stopped planning out the paintings so much. Thinking of bigger color notes first and then drawing back into those areas with a thinner brush. It’s still what I’m always trying to tell my students to do: work from the general to the specific, from the big shapes to the smaller shapes.

LG: I’m struck by how much your hard outlined edges emphases drawing. Your approach here seems to promote the vibrancy of the color, allowing the transparency of the color to take on a less modeled, stained glass or jeweled-like presence as opposed to weighty form and space with finely gradated tones and atmospheric edges. What attracts you to this approach.

Francis Sills I think a lot of that has to do with trying to capture things in front of me that are always in flux. A lot of the time that has to do with light, so I’ll seek out inconsistent or irregular light sources, or a light source that keeps changing. I find that it keeps me more engaged with the motif in front of me and offers me a sense of movement in an otherwise static motif. Sometimes I will intentionally move my position or move elements around slightly (in the case of a still life painting) to force me to fracture the forms and space in the painting. Even when I’m painting outside in my garden, a lot of the plants are in containers so it gives me the ability to move things around, or lift them up or stack them in unusual ways. I like that idea, not only for its practicality, but also there is something interesting about this idea of a container, and how it mimics the fact that the rectangle becomes a container for painted shapes.

LG: What painters, doing something similar interests you most in this regard.

Francis Sills I think there are a lot of painters now that are interested in these ideas. The list is probably too long of all the work I see on social media which I relate to. I guess I always keep coming back to Cezanne over the years. Seeing the show of his watercolors and drawings at the MOMA this past fall just keeps confirming it for me. It’s like he has this scene of trees in front of him and he’s painting or drawing anything but the trees. He’s focusing on these voids between things and is constantly searching the edges of things…it gives his work an almost hallucinatory feeling. I found that particularly true in the watercolors and drawings that were in that show, especially the late ones in the last couple of rooms. They were quite magical and surprising and he always keeps me in awe. I think there is something about this idea of structure and the slippage of form that is really interesting.

LG: Your pencil drawings of plants and flowers are wonderfully observed and sensitively handled. You seem to draw more slowly with great care and concentration. What might you be able to say about your drawing practice and how it differs from your painting approach?

Francis Sills I do find it interesting that the pencil drawings don’t have as much of that slippage or instability that the paintings do. While doing them I tend to adopt a more methodical and meditative approach, and that is apparent in those drawings. Maybe it’s the medium; the graphite being a slower build-up of form or perhaps it’s because I don’t have to think about color, just line and value. I also think it has something to do with the inherent space implied in a piece of paper versus the inherent space implied with a canvas. To me, it seems like there’s already a defined sense of space that the paper holds and by going into that with a graphite pencil and building up the forms and edges, it’s like I’m pulling things out of this void of whiteness. It’s a different experience than working on a canvas, where it’s more of an object or a thing, and I’m adding things on top of it. Like the paintings are more involved with objectness and the drawings are more to do with illusion. I’m not sure if that makes sense or I’m articulating it right, but it’s a tactual thing. I noticed that in those Cezanne drawings too, and how they differed from his oil paintings; there was more of that ‘emptiness’ that I was talking about just by the materials he used, the veils of watercolor letting the white of the paper come through, versus the solidity of his brushstrokes in the oil paintings.

LG: Many of your paintings seem to have a very active and assertive surface, with energetic marks that emphasize the horizontal and vertical relationships and underlying grid. Can you tell us something about what you are thinking about with regard to the surface and marks? hard edge – vs organic shapes

Francis Sills I’m always trying to see the organic edges in relation to the hard or geometric edge. Those points of intersection are interesting to me, where they collide or oppose each other. It brings up ideas of things that are made by man versus things that are made by God, or Nature, or whatever wording you choose. The difference between a tree branch and a piece of wood made into a railing on a deck. At Syracuse, I got heavily immersed in the work of Giacometti and Mondrian. In one sense their entire oeuvre was obsessed with this idea, these two opposing directional movements of the vertical and the horizontal. It was probably informed by their philosophy or worldview, in the case of Mondrian, Theosophy, and with Giacometti, Existentialism. I don’t think I take it there necessarily, but I do think it’s how I tend to see things visually, along these axis points or intersections. Like I’m seeing everything in relation to a grid or seeing the world through a scope. I’m not someone who uses a methodical sighting technique to build up the paintings but I understand and feel comfortable in that way of seeing. It’s built into my eyes I guess.

LG: You are having a big show soon at the Gibbes Museum in Charleston and you recently were the artist in residence there. What was that like for you? What all will be in this show? Anything you’d like to say about it?

Francis Sills I was an artist in residence there last Spring for three weeks. They have two artist studios on the first floor and it’s a way for the museum to engage the public and local artists by having open studio hours for visitors. I got a lot of work done in those three weeks and it was also great to be able to see all my recent work together and find the threads running through it all from the last few years. I was able to work on multiple paintings and collages at the same time and had some engaging studio visits. I included 11 paintings and collages in the show, with most of the work done during my residency there and some more that I did in the months before and after. I’ll include the statement that I wrote for the show here, describing the work I did and my process:

“As the twig is bent…”

The move-in date for my Gibbes visiting artist residency started with a fortuitous gift from the florist setting up for an event in the back lobby. Upon seeing that the paintings I was bringing into the studio involved flowers and floral motifs, I was offered to come by the next day and collect any leftover flora that I wanted to use as source material for more work. These gifts were to provide me with my subject matter over the next 3 weeks.

I began by using the flowers in simple still-life arrangements, responding to their color and shape as prompts to explore form. The transient nature of flowers and plants has always fascinated me; their cycles of birth, growth and death compressed into a small window of time. Gradually they changed into paintings about the layering of time and spatial ambiguity.

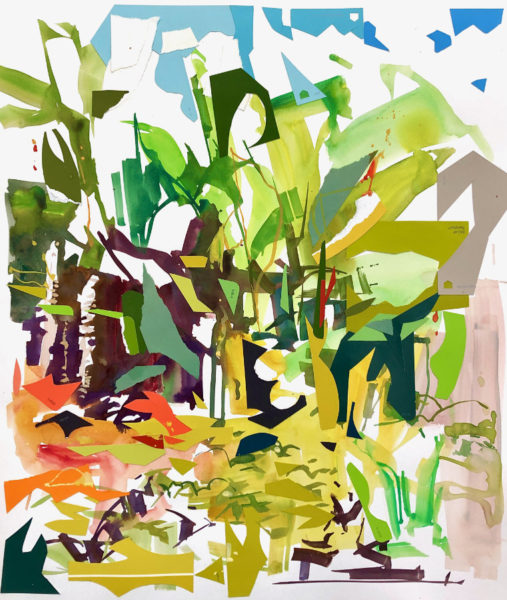

As the flowers began to wilt and decay over the following weeks, the paintings became records of their movements. I was forced to constantly alter and change the paintings in accordance with how they appeared to me each day in the studio. In order to “freeze” the flower’s shape through time and create static visual reference points to paint from, I started to trace the shadows they cast, in silhouette, of the floral shapes on pieces of colored paper. I then began to cut those shapes out and started to incorporate them into the still life setups in front of me, painting them from observation once again, with the forms ever-multiplying and abstracting. Gradually this process morphed into cutting and gluing them onto the paper paintings I was working on, collaging them layer upon layer.

I began tacking these cutout shapes to the window in my corner studio, investigating and layering the idea of looking through a pane of glass to a space beyond. The spaces in the paintings began to collapse and merge into one another so that there was a visual ambiguity between what was on the “inside” and what was on the “outside” of my studio. Things seen through the window, either dissolved or were clarified during each working session, sometimes shifting slightly, which forced me to alter the painting once again. As the whole visual reference point began to destabilize, with flowers slowly drooping and wilting, these “afterimage” flowers in cut paper remained static yet also spacially malleable.

“As the twig is bent, so grows the tree”, an 18th-century proverbial saying, reminded me of how these current paintings grew out of a suite of drawings I was doing almost 20 years earlier in graduate school. In that work, I was incorporating some of the same processes like collage, altering and repeating cut paper motifs, and ambiguously shifting spaces. This added yet another layer of reference to the notion of time passing and artistic growth. Those early influences and procedures began to shape the new paintings and became the strata that make up my work now. Those drawings, the current paper cutouts, and now decaying flowers were all composting in front of me, generating a new and multilayered series of paintings.

Wonderful and very thoughtful essay. I love those collages and especially, those beautiful drawings. The processes of working and improvising from direct observation are both reminiscent of many artists whose work is inspired by Cezanne’s example, and wholly original and fresh. The collages and oils have a directness of color and drawing that makes me think of Cezanne’s watercolors. I’m surprised watercolor or even flash acrylic isn’t part of the explorations. Thanks for the article and the powerful work.

I fall in love with art and I think that it is the main source of inspiration. Art makes me feel more sublime and I really like opening new artists to myself, understanding their own aesthetics and unique conceptions. I can say that the paintings of Francis Sills weren’t able to leave me indifferent and caught my eyes. It is so interesting to deepen into his creative activity and become closer to it. I can say that this interview was able to reveal his personality in a wonderful way and helped me to pick up some new useful information. I am amazed by the complexity of the pictures drawn by Francis and his absolutely special approach to this process of painting. The fact that I hadn’t seen something like this before this moment blows my mind because I think that Francis is unique in his field and he creates an unusual atmosphere in his pictures, paying attention to details and subtleties that is not so easy. For me, his own art is incomprehensible. Thank you loads for such an inspirational article which gave me an opportunity to delve into the world of art to a greater extent!