I recently had the wonderful opportunity to interview the painter and video artist, Ellen Kozak, over skype from her studio which overlooks the Hudson River, a subject that she has focused on for the past 20 years. The interview was further edited for greater clarity and breadth.

Kozak’s paintings celebrate the inherent abstraction gleaned from observations of the flowing Hudson River, selecting motifs from its moving and mezmerizing reflections of the sky and light. The momentary visual drama of ripples catching the light from a passing barge or the changing angle of the sun provides the poetic catalyst for her modestly-sized panels which don’t readily reveal the fact that they are mostly completed alla prima, painted in one long sitting while standing on the banks of Hudson and other bodies of water. She discusses her process at length as well as providing us with a detailed account of her unusual journey, through Japanese calligraphy which eventually lead her to her long dedication to painting this river.

Ellen Kozak’s paintings, video work and artists’ books have appeared in national and international exhibitions. Since 2000 she has had seven solo exhibitions and participated in many group shows. Collections in which her works are found include: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Brooklyn Museum, The Fogg Art Museum, The National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, The New York Public Library and Yale University Sterling Memorial Library among others. Between 1992 and 2017 Ellen Kozak taught at the Pratt Institute. The Hudson River Museum mounted a solo show of her paintings in 2001-2002 and in 2018 the Museum exhibited a solo show of her four-channel video installation, riverthatflowsbothways, a collaboration with composer, Scott D. Miller. Hudson River Trilogy: Ellen Kozak, her solo show at The Katonah Museum of Art in 2009-2010, included paintings as well as her video, Notations on A River, commissioned by The Katonah Museum of Art.

In a review in Roll Magazine.com Claire Lambe wrote:

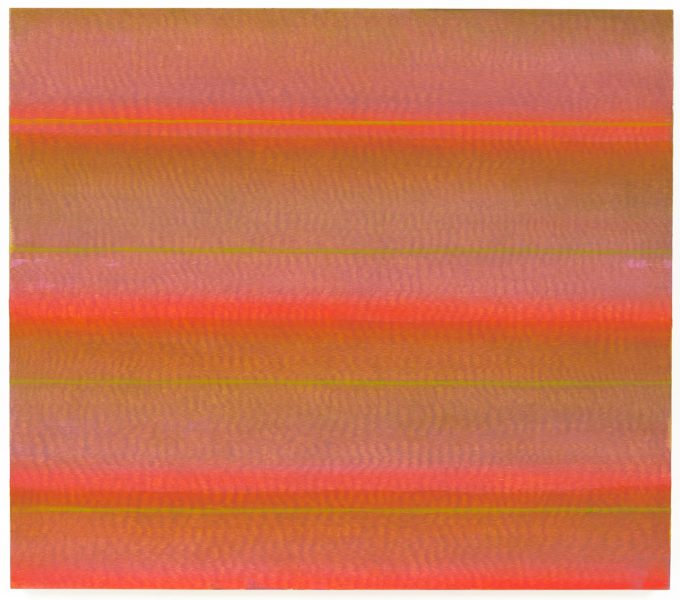

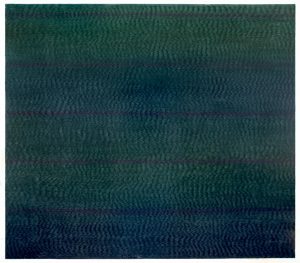

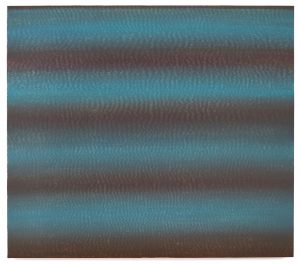

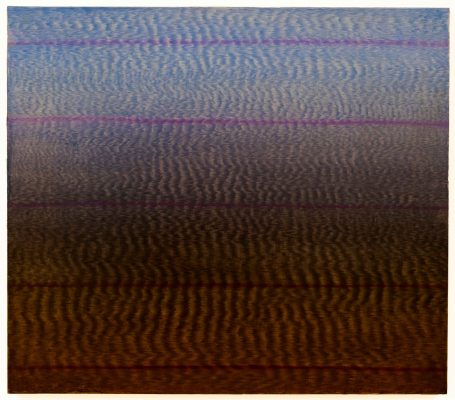

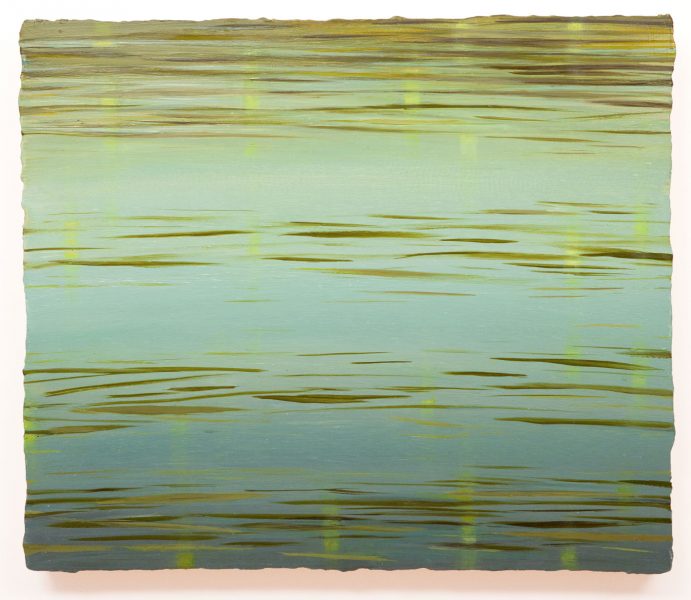

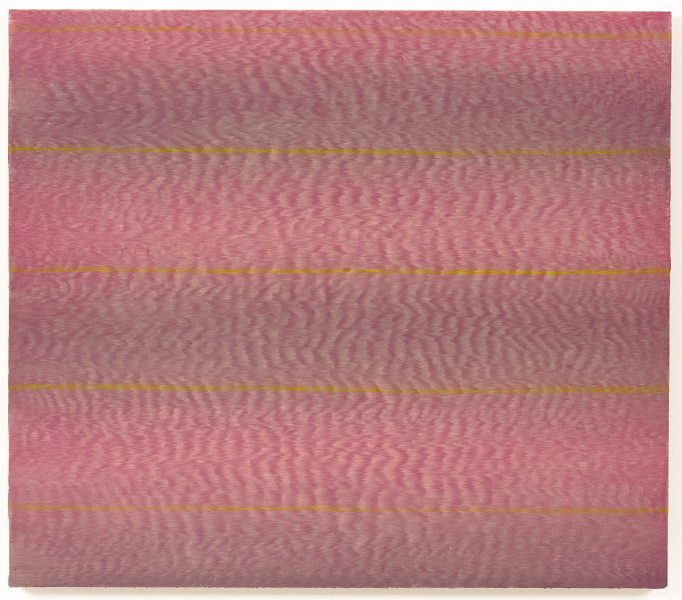

Kozak’s oil paintings walk the line between representation and abstraction. Her particular interest is in the equivalences in the behavior of her subject and her materials, “I use paint as a mimetic medium, letting it physically perform like my subject. Oil paint and water share properties of viscosity: paint directed by a brush emulates a river’s surface stirred by wind or pulled by tide.” In the paintings, thinly painted on wood panels that have been prepared with a hand-made dry gesso, rifts of shimmering color evoke movement and, in some cases, the vibration of light on water, in others, the unfathomable depths. Over the years that Kozak has engaged in this work, the paintings have become less representational and more abstract, more reductive. Movements of color and form that, in earlier paintings, were descriptive of the water’s curves and arabesques have, in this recent work, been distilled into quite formal abstracts, many with a strong linear movement, but generally remaining faithful to the horizontal surface of the river.

from the bio on Ellen Kozak’s website:

The activity of painting on-site is a fundamental cornerstone of Kozak’s practice and her work, which extends to artists’ books and video. In 1996 Cross-Cultural Communications published Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes: Notations on a Landscape. This limited edition includes a foreword by Dore Ashton with Stephen Mitchell’s translation of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem, Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes. In 2005 her artists’ book Tree of Names and A River was created at Dieu Donné Papermill with grants from the George Sugarman Foundation and Pratt Institute. Kozak has been awarded additional residencies at Yaddo, The Blue Mountain Center and The Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Reviews of her work have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Art in America, Art & Antiques and other publications.

In 2012 her residency in Auvillar, France, the Prix Moulin à Nef, provided her with a studio on the bank of the Garonne River where she painted and continued working with video. Kozak has studios in New York City and in the Hudson River Valley.

Larry Groff: Please tell us how you became an artist?

Ellen Kozak: I was interested in art from a young age. I drew from the model starting at age thirteen. My teacher, Aida Wheedon, studied with Hans Hoffman and Thomas Hart Benton at the Art Students League. In high school, I took art classes at C.W. Post College and I took classes with Dan Daily and George Greenameyer at the Haystack Hinkley school of Arts and Crafts in Maine. These were wonderfully encouraging experiences. After my freshman year in college, I had an apprenticeship with the sculptor Alfred Van Loen, who was an inspiring teacher.

Larry Groff: I understand you attended Mass. College of Art as well as at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies, eventually concentrating on learning film and video. What was all that like for you then?

Ellen Kozak: My earliest sense of identity as an artist began in the foundry at Mass Art. Pouring bronze was incredibly exciting and visceral. Another transformative experience was a class in film and experimental music with Paul Earls, who was also a Fellow at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS). During that year my interest in video expanded, I was looking at Woody and Steina Vasulka, Joan Jonas, Dara Birnbaum, Nam June Paik, Peter Campus and others. In my senior year at Mass Art, I cross-registered for a class at MIT taught by CAVS Director, Otto Piene. The following year, in graduate school at MIT, I worked mostly in video. Peter Campus taught a seminar. One of Nam June Paik and Shuya Abe’s video synthesizers was temporarily housed at CAVS. It was a wacky contraption that generated images from electronic waveforms and I used it for part of my thesis, a 4-channel video installation.

Larry Groff: What all were you doing after leaving art school?

Still from Sketches of a Master, single- channel video,1985

Media Arts, Volume 1, Number 7 Autumn 1984

Ellen Kozak: Well, I taught Film and Video at UMASS’ Boston campus during the year I was a Fellow at CAVS. When this job ended, I had various jobs programming computers and in 1982, after responding to a job listing for English teachers in Mother Jones Magazine, I moved to Japan. My Portapak came with me. Barbara London introduced me to video artists in Tokyo and I received a little support from Sony and JVC. While teaching English, I also had some exhibitions and screenings. I did some lecturing at Seian Art University in Kyoto and wrote about video in Japan for Media Arts.

I lived in a semi-rural neighborhood surrounded by rice fields. Everything I encountered in Japan was so radically different that my approach to video changed. My pieces were documentary in nature, portraits of people that I came to know in Utsunomia. Hiraishi Hironori, a master of shodō became a friend and the subject for one of the videos. He was one of five sons of my elderly next-door neighbor who frequently invited me for tea and sweets. We called her O bāchan, grandma. One winter morning she was found dead in her home and as the occasion unfolded, I met her son Hiraishi Hironori. He appreciated that I was company for his mother and invited me to his studio which I visited frequently, especially on holidays, and I asked if I could film him at work. The portrait, Sketches of a Master, begins with his morning chanting practice at the tokonoma in his studio. I began to study shodō, the traditional Japanese artform of calligraphy.

I‘d been interested in shodō before moving to Japan and I found a calligraphy class as soon as I arrived in Utsunomia. The students were all older Japanese women and not a word of English was spoken. I liked the contemplative practice and the immediacy of shodō that was not so with video, or at least with how I was using it.

Arriving back in the US after almost two years in Japan, I completed my video pieces. There was a screening at the Boston Film and Video Foundation, and I joined a Boston-area printmaking collective. I wanted to make very large prints with the type of brush I used for shodō. My inspiration came from memories of the flooded rice fields near my home and of the mirror-like reflections in the water as the seedlings began to sprout. The build-up of ink on the monotype plates became too thick to run through the intaglio press so I got my own painting studio that’s when I started to paint.

Larry Groff: I’m curious to hear you explain how you transitioned from the studio with printmaking and video to painting outdoors. What led you to paint outdoors?

Ellen Kozak: It was at least a three-year transition during which I moved to New York with the Griffen 40 x 50-inch press. A few important things happened. I discovered the landscape photography of Eugen Atget whose work was unknown to me and I began drawing regularly from the collection of Atget’s prints at MoMA’s Photo Study Center.

I was drawn to their subtle tonalities, his beautiful craft, and use of the early morning light in the Paris Parks. I had a solo exhibition in Boston with both my paintings and prints and my Yaddo residency in 1986 put me in closer contact with nature.

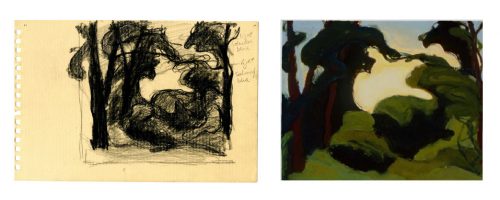

At a second Yaddo Residency, I met artists that had been renting summer houses and studios in the Catskill and Hudson area, it sounded great. The following year I rented a house in Athens, NY and started out by using my drawings, from Atget’s photographs, as studies for oil paintings. The house was on a stream, surrounded by woods in a rocky grotto where the crepuscular light felt like the atmosphere in Atget’s photographs. It felt like a natural transition to move outdoors.

Out in the landscape, I thought in a different way, I did less conscious thinking, or used a more intuitive part of my brain. I experienced time differently. The experience of working on-site became more intense at the second studio that I rented in Athens. It sat directly on the west bank of the Hudson River. Perhaps I was connecting to a familiar state that I experienced when I was studying shodō. Observing water is deeply contemplative. I have not found anything like it

Larry Groff: So, would you say that being outdoors painting was appealing to you not only for the visual satisfaction but also for the way space opened up an emotional connection?

Ellen Kozak: There is an instant intensity, yes. The three-way conversation between my subject, painter & the canvas, becomes very very alive. I sense that I step across a threshold into a kind of liminal space. It’s a different kind of space. In Dore Ashton’s foreword to my artist’s book, Orpheus. Eurydice Hermes: Notations on a Landscape, 1996 she referred to this condition as “being only eye”.

I think this is not an uncommon experience for painters. You might be painting for eight hours straight, time stops, and the hours go by so quickly because you are hooked-in, really hooked-in to the moment or to the many moments. This is especially so because much of my painting is done alla prima and there’s the tension of trying to get the paint right.

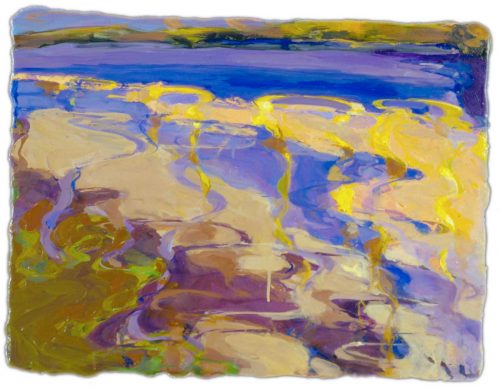

Hudson River Primer #16, oil on panel, 11 x 15 inches, 1997-98, collection of the Hudson River Museum

Larry Groff: Can you tell us about your process? Do you consider your outdoor paintings as studies that you complete in the studio or do you make everything on-site?

Ellen Kozak: For years now, I begin painting directly on the gessoed wood panels on-site without studies. Years earlier, when I was painting on-site with watercolor and egg tempera, I used these paintings as studies. This didn’t last more than two years. But I also saw the egg tempera paintings in their own right, as those below.

The images in the artists’ book that I mentioned earlier, Orpheus. Eurydice Hermes: Notations on a Landscape are made directly from the egg tempera paintings that I painted on-sight. I was painting from a promontory overlooking the Hudson River and I imagined that the river and riverbed were the landscape through which Eurydice travelled, following Orpheus to the world above.

Larry Groff: I understand you make your own particular type of gesso and that it is an important part of your work. What all is involved with this?

Ellen Kozak: The surface is a critical part of my process. After I layer-on the dry gesso it is sanded, it feels like a baby’s bottom, silky soft and with a glow. Then I seal the surface with gelatin. I like Knox gelatin because it’s more finely ground than rabbit skin glue crystals and it dissolves more easily.

Larry Groff: The same kind of gelatin sold in the grocery store?

Ellen Kozak: Yes, it’s unflavored Knox gelatin, very cheap and it takes little time to dissolve so you don’t have to heat it on a burner. It’s on the shelf with the Knox Jell-O, I buy it in bulk.

I also use the Knox gelatin in the gesso. My paint is very thin, people think that there are many layers but that’s not the case. I keep the paint fairly thin which allows me to retain the glow coming from the gesso. I let the light emerge from the ground itself. Other gessoes can have an unpleasant slippery surface, but the dry gesso has a resistance to the tacky oil paint, it will tug on the brush some. I’m using the same gesso recipe since 1988.

Larry Groff: I’m looking at your paintings on the wall behind you, as seen through your webcam. It’s hard to read the surface sheen, are they more matt or satiny? Does this gelatin seal and help prevent the colors from sinking in? Are there aspects about your surfaces that a viewer might miss by just looking at a jpeg online?

Ellen Kozak: That’s a great bunch of questions. The gelatin seals the sanded surface otherwise, as you say, the colors would sink in. This way I can use the gessoed surfaces’ porcelain-like quality, it has a polished luminosity. It’s the luminosity from the ground that adds the glowing quality you’re detecting in the webcam. I use a standard medium, some colors as you know, like earth colors, may appear dryer but since I do a lot of mixing on the painting itself, the dryer and oilier colors wind up getting mixed which gives the overall surface uniformity. I apply the paint in one wet-on-wet session. I can count on one hand the number of paintings that needed varnish.

Larry Groff: Wow, that’s surprising.

Ellen Kozak: I don’t labor over the painting. Over the past five years, my work appears more abstract and more direct. There has been an interesting shift after I built a new studio. Within that first session I need to accomplish everything that I’m going after. Generally, I don’t work on top of it.

Larry Groff: So, there’s no layering or anything.

Ellen Kozak: No.

Larry Groff: To me looking at a little jpeg on the computer I get a different notion of how the painting must have been made so I’m amazed to hear that. It seems so detailed and the marks and patterns are so specific that I imagine it would be done over many sittings in multiple layers or sections I wouldn’t have thought that this was a premier coup painting at all.

Ellen Kozak: I find this reaction from many other painters. Like yourself, people imagine that a small brush is used to reiterate a certain kind of mark. I paint with very large brushes.

Larry Groff: Really? How large?

Ellen Kozak: Well, not push-broom size but they are about 3 inches

Larry Groff: Wow! That’s incredible.

Ellen Kozak: The paintings are generally under thirty-six inches in either dimension, so I suppose it sounds like a pretty large brush to use on this size of a painting. I work on the painting almost entirely out of doors. When I need to paint further, I work indoors on the same paint layer. I sort of go back to the gessoed surface and re-invigorate the original paint. I don’t know how this happens. It’s weird. The part of the painting that is added after the painting dries is the linear element, those violet lines in the painting you are looking at. Can you make those out?

Larry Groff: Yes, I think so, you mean those horizontal lines?

Ellen Kozak: Yes, they are narrow and a somewhat transparent violet. I use a liner brush toward the end, usually when the paint is dry which could be days or weeks. But the added color is in my thoughts while I’m working out of doors. I think of it as representing another mode of appearance such as the sparkle, glint, or shimmer you might see of light on water. And it can also imply the horizon.

Larry Groff: What would you say about the relationship between the way you use your paint and your motif, is there a connection?Ellen Kozak: There is. With one aqueous medium, oil paint, I am describing or interpreting the behavior of another so there’s a mimetic relationship. Though both have different viscosities, oil paint and the water share this property. I use the physicality of the paint to perform in ways similar my subject. Pushing, pulling or dragging a loaded brush across the dry gesso leaves a pattern—a visual stutter—a phenomenon similar to the pattern that a breeze makes when ‘brushing’ the surface of the water. The relationship is intrinsic and contributes an inherent authority. Does this make sense?

Larry Groff: Yes. That’s a great way of putting it. I can also see a relationship with Japanese calligraphy and the contemplative aspects of painting outdoors.

I’m surprised to hear that you often paint in one spot for more than 3 or 4 hours as the light changes so much. The motif changes so much, especially with the moving water and light, it becomes many different subjects over the course of such a long time.

I’ve read that Cézanne sometimes painted outdoors for many hours in the same spot – with the light changing dramatically, however, his painting wasn’t necessarily about the light at a specific moment of time. With that in mind, I imagine that some plein air painters might say that Cézanne wasn’t making “observationally-correct”painting and that you just happen to be painting outside. So, what might you would you say to these naysayers?

Ellen Kozak: Yes, I understand your point. I’m not a plein air painter for sure and I am not trying to capture a specific moment. However, I do work empirically and from direct observation. That’s just stating a fact. In between our emails back and forth, I keep thinking about your point. One additional challenge with my subject is that it’s in constant motion. Even if I worked only for an hour, my motif is in constant flux. Undoubtedly, some plein air painters contend with this as well. As you alluded to earlier, the entire gestalt of working outside is a necessary state or condition that’s both physical and cognitive.

Landscape painting can be an extreme sport if you consider the mosquitos, the bugs landing on the painting, wind blowing-over the easel, protecting yourself from the sun and the incoming tide, and figuring out what to do about the loo.

Going back to your question about observation, as you can see my color is not always the color that one would observe. I try to preserve the relationship between the colors. As you just pointed out, the motif I’m painting is in constant motion. When the river’s surface is still, it mirrors the world above. When the surface is choppy, the reflection can be a complex texture. I love this and I’m fascinated by the way an intermediary representation of the landscape, such as reflective surface of water, can assemble a new picture plane. I use the river as a kind of indirect method of observation. I recognize that my paintings appear abstract but when I’m working, I feel like I’m a painting a literal representation of what I see.

Larry Groff: What about the notion of the grid and your mark-making with horizontal and vertical relationships and movements? I’m wondering if how you make your marks also relates to the calligraphy you’ve studied. Especially since you’re working with such a large brush.

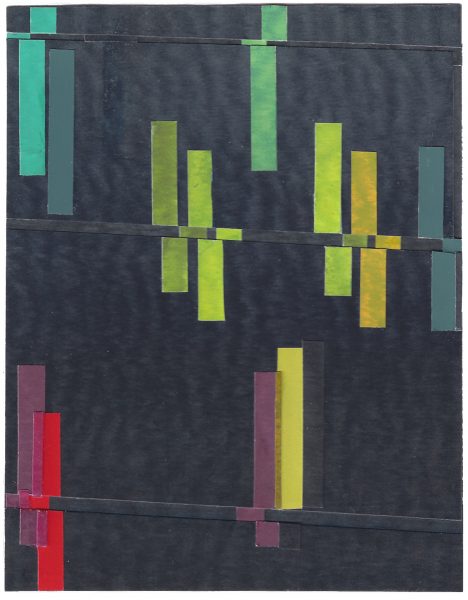

Ellen Kozak: I never thought of this but possibly. In shodō one is vividly aware of the two axes. The grid-like orientation you’re observing might also have something to do with the scan of a TV monitor and my background in video. One of the channels in my video installation, riverthatflowsboth ways is directly related to calligraphy.

Two recent paintings from last year reflect that in their title. Joan Jonas’s video, Vertical Roll, made an impression on me in the mid ’70s.

In addition to natural phenomena, I also pay attention to optical phenomena, such as the illusion caused by after-image, most evident in paintings between 2011 and 2014. They appeared in a kind of lozenge-like shape.

If you were to watch me paint, you would see my arm making the same horizontal motion for hours and hours, large left to right, right to left sweeping motions. It looks ridiculous. But also, the dispersal of paint from my rhythmic strokes is horizontal and the pattern that emerges from the brush’s stutter is vertical. Even though the horizon is not part of my view it is certainly implied. As upright creatures, our relationship to the horizon is as a perpendicular element which also defines the way we experience gravitational force. I think of the vertical axis as figurative.

Larry Groff: Do you use bristle or sable brushes or something like squirrel brushes?

Ellen Kozak: I like synthetic brushes. They are flexible and springy; sort of like flip-flops and I use a lot of paint. I remove a lot of the paint while working. There’s not a lot left on the panel by the time I’m finished. I rely on the quality of spring in a brush, the viscosity of my paint and its degree of transparency. I also use old #2 bristle brushes to pick off the insects that land on the painting. It works better than a palette knife.

Larry Groff: They don’t look like they are painted with impasto. You must use a lot of medium then?

Ellen Kozak: Yes, I do.

Larry Groff: The Hudson River has been your motif for about twenty years, your earlier work showed a greater expanse of the river with more of a horizon line or suggestion of one such as seeing parts of the riverbank or trees or other elements. Your more recent work is much flatter, focusing on just the water itself and you eliminate most of the identifying surroundings.

I’m curious if you could talk a little bit about how space has evolved in your work. Is the flatness an important part?

Ellen Kozak: I understand what you’re asking although flat is not a word I’d think of using.

Larry Groff: I misspoke, I meant that your paintings zoomed into the river so that the water no longer showed a wider perspective, where everything is parallel to the picture plane like what you might see in a like a color-field painting. There isn’t a representational type of deep perspectival with a horizon line or atmospheric space.

Ellen Kozak: True and well stated. Up until 2000, I was painting from that promontory I mentioned earlier, so my view encompassed more of an expanse.

The horizon has crept from my paintings since I moved to my studio in New Baltimore, however, it’s still implied. And for a number of years, I’ve been limiting my perceptual intake to a small section of the river, oftentimes beginning right where I am standing. There was a period of time, culminating in my solo show at the Katonah Museum when I included no horizon but there was a sense of a perceptual expanse.

Within this circumscribed area you could say that there are at least three spatially distinct planes that my paintings kind of squish together. One is the physical surface of the water itself, that may be patterned from wind, current, tide or a man-made disturbance such as from the wake of a boat. Another plane is the volume or depth of the water that is visible, depending on the degree of transparency, translucency, or turbidity. In a third, “reflective”, plane, the reflection may be mirror-like if the surface is still. And if it’s not still, the reflection may be faceted, combining reflections that materialize from different directions. All these distinct spatial planes get compressed together in my paintings and are made to coexist in one picture plane, not without depth, as you so carefully stated, but with a space that appears more flattened. It’s a conglomeration of perceptual space; the river is my synthesizer.

Willem de Kooning did something like this when he merged picture planes by pressing a sheet of newspaper onto part of a painting. This left a pleasing tacky texture and compressed or re-synthesized his picture plane.

Larry Groff: So, the color decisions you make in your paintings seem very sophisticated. I understand that you teach a color course at Pratt, which must play a role in your thinking about color.

Ellen Kozak: Color is how I think. When I fell into teaching Light, Color and Design I began learning a tremendous amount. I’m not teaching now and for the first time I’ve started making collages with Color Aid papers as in the collage above. The illumination of the river from the nighttime passage of barges, tugs and tankers is magical.

The studio class I’ve taught combines perceptual, conceptual, analytical, and expressive approaches and is at times like a lab. Theory is a part of the curriculum, but it’s not taught separately from direct observation. Students seem to be totally turned on to the approach. Understanding color’s complexity is powerful and students see this, it’s a means to identifying the qualities of things, in the material world, quite independent of what things are.

Larry Groff: The color is a very exciting part of the work. It seems a central concern that you do very well.

I’m curious if you could comment on other, perhaps more illustrational or commercial ideas about color. These days, students—especially those involved with illustration and computer animation—might want to view color, less in terms of observation and more in terms of what a photoshop eyedropper picked for an RGB number or maybe the scientific properties of an object’s material like the index of refraction or the properties of the light through a prism, or the degree of how reflective or translucent it was. Maybe if these students wanted to paint, they might be more drawn to something like the Munsell system of color – so they felt they were being more exact and measured. Is this something you run into teaching?

Ellen Kozak: I think that in every artistic practice, whether it’s animation, illustration or painting, learning to see perceptually is powerful, even when one works digitally. My experience is that across the board students are profoundly interested in observational study and enjoy exploring color phenomena and relativity.

You mention systems designed to explain color… there’ve been so many. It’s interesting that not one of them, by itself, does the job. You also refer to the use of a prism as a tool. While the visible spectrum can be separated into its component wavelengths, it’s also an example of the limitation of a common convention. This spectrum works only as a schematic representation. What about colors in the red-violet range? They exist even though they cannot be assigned a wavelength. Other conundrums follow in explaining colors that we can plainly see but can be found on the electromagnetic spectrum or within various theories; metallic, fluorescent, and day-glow colors. Color’s elusiveness is one reason why it’s so interesting.

Larry Groff: I’ve talked to a few painters who used the Munsell system of color and they swear that it’s the best way to determine and mix an exact color, saying this allows you to mix this color again and again with an exactness that a more intuitive approach is less capable of. This seems useful for commercial applications but in fine art painting, it would seem to run contrary to an emotional and artful response to color.

Ellen Kozak: You know about metameric color, right? Any color can be mixed in any number of ways. Art conservators have to do this all of the time. Most color theories recognize that it’s necessary to think of color in three dimensions and the Munsell system’s three-dimensional model is very useful. Once you can identify these separate dimensions it’s quite possible to mix a color in any number of ways. Intuition does not suffer from too much knowledge.

A good number of years back, there was a really interesting exhibition of Van Gogh’s paintings in the Robert Lehman Gallery at the Met. The paintings were removed from their frames and the paint under the taped edges of the canvases was revealed. The original colors were shocking because paintings like his sunflowers, which we’ve seen for all of our lives, apparently looked quite different when Gogh painted them. There was an immediate cognitive disconnect.

Larry Groff: I think he sometimes used a chrome yellow and lake colors that were fugitive, sometimes making them more impasto in thinking having more paint might slow down the fading process, I remember reading something about that. Of course, there is the famous example of the Sistine Chapel, the color difference after the famous cleaning was astounding.

I understand that you are involved with an organization, Hudson River Keeper – https://www.riverkeeper.org/ an environmental group that is working to protect the Hudson River and address the effect of climate change on the river, can you say something about that? Do those kinds of issues come to play in your artwork in some form?

Ellen Kozak: My awareness and involvement with Riverkeeper came through painting along the river’s shoreline, it’s like having a front-row seat at the reality TV show, “Hudson River Rising”, (Riverkeeper’s theme for 2020). It is frighteningly clear that the rise in sea level is not an abstract eventuality. It is measurable. I’ve been measuring, and it is shocking. Riverkeeper’s mission is to protect the environmental, recreational, and commercial integrity of the Hudson and its tributaries, and safeguard the drinking water of nine million New York City and Hudson Valley residents. I also swim and kayak on the river.

When I began painting on the shoreline in 2000, I noticed a fishing boat, with the Riverkeeper logo, traveling up-river and down every three weeks or so. I learned that it was Riverkeeper’s Patrol Boat. My interest developed from what I was seeing on a daily basis and it expanded from there.

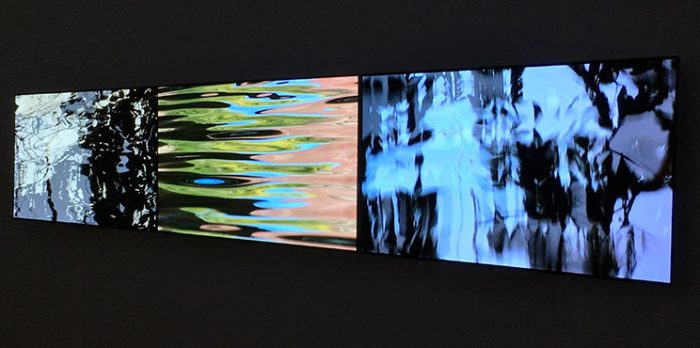

But, to your question about how my involvement with Riverkeeper comes into play in my art, I’d say that it definitely does but it is indirect. I don’t incorporate or infer political meaning or content in my paintings. The same is less true of my video work. In any case, because my work is abstract, viewers probably need to be informed, through a brochure or wall text for example, about the indirect political/environmental references in my work. Music too is abstract, but it has the power and potential to reach listeners directly and emotionally. The composer with whom I collaborated on our video installation, Scott D. Miller, brilliantly evokes tranquil but unsettling states that issue presentiments of destabilizing undercurrents throughout our installation at the Hudson River Museum. Imagery of tankers and barges on the Hudson are woven into riverthatflowsbothways along with similar imagery from the Garonne River in France (where I have had two residencies). Whenever it is possible in galleries and museums, I try to create public programing to introduce Riverkeeper’s important work. I also participate as a member on their board of directors. I hope this addresses your question.

Larry Groff: What else would you like to say about the campaigns Riverkeeper is working on?

Ellen Kozak: Riverkeeper is litigating to force General Electric to complete the removal of PCBs that GE dumped into the Hudson between 1947 and 1977. Also, the Army Corps of Engineers’ ongoing dumping of contaminated dredging spoils onto Houghtaling Island is being fought. The photo above shows the Riverkeeper Patrol Boat beside the barge discharging the contaminated spoils (it is directly across the river from my studio).

The Hudson River is experiencing a period of reindustrialization. For the last ten years, transportation of crude oil, on so-called “bomb trains” and on tankers and barges, going from Albany to the ports of NY and NJ endangers residents and the environment. Riverkeeper put an end to the proposed installation of forty-two Hudson River anchorages in the river to serve primarily as parking lots for barges carrying crude oil. In Greenpoint, Brooklyn, Riverkeeper is raising awareness and fighting in court over the millions of gallons of oil leaked from ExxonMobil’s facilities into the soil and groundwater. Riverkeeper was instrumental and is now closely involved in the safe shutdown and decommissioning process for the Indian Point Nuclear Reactor. And, Riverkeeper is partnering with the Newtown Creek Alliance on their four-part vision plan for the remediation and restoration of the Newtown Creek.

Larry Groff: This reminds me of how Fairfield Porter was a committed environmental activist, with the issues around DDT and such, but didn’t paint anything political in his mature work, despite his beginnings as a social realist painter.

Larry Groff: I want to ask you about your video work. You are still involved with this I understand, how does your video relate to your paintings now?

Ellen Kozak: Yes, I am working with both and there’s an exciting momentum. I resumed working in video after a funny camera accident. While I was painting one day in the fall of 2008 I tried to take some quick photos with my cheap point-and-shoot but instead, the camera was in video mode. Shooting into intensely bright sunlight, a no-no as you know, the camera’s chip started burning up. It took a few minutes to die and in its final seconds of life, it recorded a brilliant strobing rhythm in an almost fluorescent red-violet. It was an artifact of the camera’s own death that got recorded on the memory card.

Ellen Kozak: I liked the strobe-like video rhythm, the river’s motion, and the flashes from reflecting sparkles of light so much, that I wanted to repeat it. I began buying used cameras, of the same type, on eBay to recreate the event. But I was never able to get something as beautiful as the first camera’s swan song.

People have asked if the images in riverthatflowsbothways are of my paintings. This still surprises me because while the works are related, I wouldn’t have supposed one could be taken for the other. But I understand why there can be confusion.

Circling back for a minute if you don’t mind Larry, earlier we were speaking of the river as my “motif” and it’s a useful word but I feel like something is left out because in a way, the river can become nearly invisible as I paint it. In a way, my motif/the river, disappears into the phenomena of itself and of the surrounding phenomena. So maybe we should think of my motif/the river/water more a-kin to an optical instrument; a lens-like device that has synthesizer-like properties also serving as a means for indirect observation. In recent years I’ve noticed that the synthesizer-like properties of the river, whether I’m painting or shooting video, relates back to my early brush with Nam June Paik’s video synthesizer.

Watching the surface of bodies-of-water is an interesting way to indirectly observe the world. This can create collisions and magnify attributes by imposing distance that is both perceptual and psychological. Mediated observation suggests metaphor and also renders what is known, to be equivocal.

Recently I’ve noticed an inverse relationship between my paintings and video work. While my paintings of the river collapse hours of observation into still surfaces, my video pieces are largely composed from still images of that same subject, which by nature is in constant motion. Subverting expected characteristics of each medium creates unexpected paradoxical disjunctions that continue to fascinate me.

Larry Groff: Thank you for spending so much time and consideration with explaining your unique background and process so eloquently. It is exciting to see the ways your work expands the possibilities for landscape painting into fascinating new directions with such a modernistic and poetic sensibility. I also want to ask you – are you having any upcoming exhibitions or ways to see your work in person currently?

Ellen Kozak: Thank you Larry. I have been a veteran reader of your blog and am pleased that you found my work appropriate for Painting Perceptions. My paintings are included in a show at Zurcher Gallery in New York City that runs concurrent with the dates of the Frieze Art Fair (in NYC) Randall’s Island Park, from May 4 –10, 2020.

My appreciation for Ellen’s work is endless. Reading about her method and enjoying the images of her work, as I scrolled through this lovely article, reminded me of what a powerful idea the Hudson has been for generation after generation of creative artists. To be part of the Riverkeeper organization and have a hand in the preservation of “the river that flows both ways” has been the high point of my career.

I have one of Ellen’s canvases in my office – it will be the first thing i reconnect with, when we all finally get out of quarantine. It’s funny – I walk by the Hudson each day and it gives me joy – but there’s something about the paintings and photography of the river that our partners in the art world have created that I just miss so much right now.

Ellen’s work has a quality that transcends the senses. It carries the whiff of the river, its subtler sounds. Perhaps I can say this because I spent a night immersed in what were distinctively deep water dreams a few feet above the level of the Hudson at Scott and Ellen’s place. Her paintings will always evoke that experience. While they have astute abstract qualities, her paintings never for a moment escape the dream of water for me with a range of sensory associations beyond what is apparent.

I enjoyed the depth of the interview., methods and ascetics of the picture plane. Thank you, Larry.and Ellen

Ellen Kozak mentions that her repetitive, spellbound painting motion can look ridiculous. Well, from the ridiculous to the sublime. Thank you for the excellent insights into a wonderful painter’s history, methods, perceptions.

As a great admirer of Ellen’s work for some time, I greatly enjoyed this in depth interview. Her words give much insight into her process, and her concepts. Very illuminating. It is inspiring to learn more about the thoughtful evolution of her art. And to think more about links in common to my own work. Thanks so much for this worthwhile interview and your larger project!

The depth of this interview is fantastic. Building from her early influences into the thoughtful and intuitive way that Ellen developed her unique way of seeing the river. You also captured the interactions between the river and how she thinks and perceives. Ellen was so eloquent in the way her technique influences the look of the work itself. This is one of the best artists’ interviews I have read. Thank you both.

We both loved the interview. It was fascinating to learn about your life in art over the years and how your thinking and work has evolved. One’s response to art is so individual. Works either speak to you or not. I have always loved your pieces; I find them beautiful and mesmerizing.