I am very pleased to be able to share this email interview with Elizabeth Geiger and I’m grateful for her generosity to be able to hear about her experience and insights into her process and intense engagement with painting.

From Geiger’s website:

Elizabeth Geiger majored in painting at the University of Virginia and continued her studies at the New York Studio School and the Vermont Studio Center. She is married to figurative painter Philip Geiger and they have two children studying art in college.

Geiger has won a fellowship from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and shown regularly throughout the East Coast. Her work is in the collection of the Sheltering Arms Hospital Richmond as well as the Clay Center Museum of Fine Art in Charleston, WV.Known for her dramatic still life paintings, she has recently also focused her painting practice on landscape. Along with her regular teaching at the Beverley Street Studio School in Stuanton, VA, she has been a visiting artist at the College of William & Mary and the Kentucky College of Art & Design, spoken at Washington & Lee University and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, taught landscape painting at the Mount Gretna School of Art and leads workshops throughout the Eastern United States.”

Elizabeth Geiger is represented by Gross McCleaf Gallery in Philadelphia, PA.

From April 2010 American Artist by John A. Parks

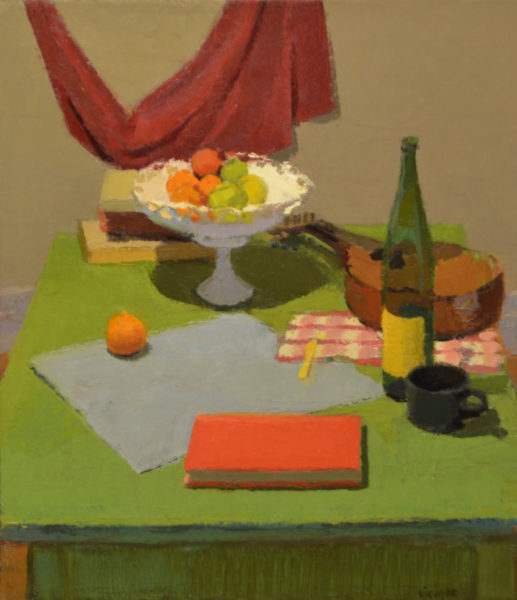

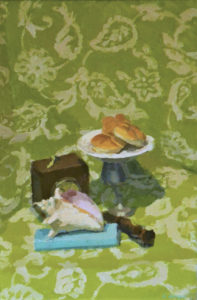

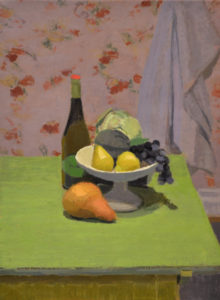

Although Geiger has often painted the figure and landscape, she finds that she tends to concentrate on still life. “The still life has become predominant because of the freedom it gives me to choose arrange, and edit a setup,” she says. “Or as a friend of mine puts it—I am the writer, producer, and director of my own opera.”

When asked how she would like viewers to respond to her work, the artist is hesitant. “In some ways, I don’t want to pin it down,” she says. “I don’t have an easy answer or a written agenda, and I’m amazed when I meet a contemporary artist who seems so sure about what their work is doing.”

The artist does say, however, “Visual beauty is my first desire, not narrative content. I would like the viewer to be left with the desire to return to the painting. I hope that the visual experience of the whole picture adds up to a great deal more than the mere process of description.”

From an essay written for the Gross McCleaf gallery:

Geiger’s approach to painting is a balance of immediate gestures and calculated decisions. Her brushwork contains an energy that is closely connected to the carefully chosen objects that appear in her still life compositions. Geiger begins by finding something in a familiar object or setting that surprises her and, while painting, she often stands in a position looking down on her motif in order to create an intimate viewpoint.

Geiger says of her work,

“My paintings begin with a feeling of excitement—a rightness with the light. A feeling of space, a group of forms, a chord of colors can all start the process. A good set up feels like a memory—one I would like to have. My objects are so familiar at this point that I am free to alter the arrangement at any time while I am working. My concern has begun to shift from the meaning of the objects to the light on them as the subject. I continue to reinterpret still life painting. Inspiration can come from a landscape, a portrait, a poem, or an abstract pattern. My original motivations or musings about the set up may not remain clear, but I hope the drama and mystery evoked by the objects and the paint itself stay with the viewer.”

Elizabeth Geiger will be teaching two 5 week Zoom classes this winter through the Beverley Street Studio School – Drawing the Still Life: Location Mark and Line Drawing, Fridays January 15 – February 12, 2021 and Painting with Compliments, Fridays February 19 – March 19

Larry Groff: What lead you to become a painter?

Elizabeth Geiger: When I was about 10 or 12 my father told me that the portrait of a man wearing a turban in our living room was painted by my grandmother. Surprised, I asked if there were other paintings and my father said, “No – she stopped painting. She said it was too hard.” I was curious …was it really THAT hard? Well, Grandma, it is. But it’s more fascinating than anything I could imagine.

LG: I understand you first majored in math before you changed to become an art student. I’m curious if geometry or other mathematical aesthetics like dynamic symmetry has ever played a role, either conscious or unconscious level in your compositions?

Elizabeth Geiger: My first art classes at the University of Virginia was a refreshing change from my prep school education of lectures where I would read, memorize, and then write a paper. School had been predictable. I liked math best and planned on becoming a math teacher. But math could be creative—reviewing homework in advanced math classes was like an art critique. Students solved problems on the board and the teacher discussed how the problems were solved and if the student could have done it better. In my math classes, simplicity was the goal. If problems were solved in a more direct way with fewer steps, the solutions were praised as elegant. I would return to this aesthetic later in art class. Some math professors in college would ask me to draw things on the board for them like a Torus (donut shape) rotating in space. I definitely have a mathematical mind—but I see the connections between math and art, not the differences. Mixing colors and composing are about proportions, drawing about finding an underlying geometry, and studying higher math felt cosmic and spiritual.

LG: What was being an art student like for you?

Elizabeth Geiger: I remember the first art class I ever took. It was drawing with Carol Robb, a visiting artist at UVA. The first day, she had us get out various pencils and start drawing. People around me were chatting and seemed to be having a good time—there was a loud radio playing the Clash—but I remember being serious, having no idea how to do this, but feeling it was very important. By the end of that first class, I knew I had to study art.

I had never taken an art class until I was 19. In my college art classes, I felt over my head since there was so much involved with making a painting. I was trying everything and being a sponge. Color was what I cared about and determined the artwork I looked at early on, Van Gogh, Matisse, Fairfield Porter, and Louisa Matthiasdottir.

LG: Do you think going to an art school is necessary to be a good painter?

Elizabeth Geiger: I think a good art school can help you develop technical skills and refine your judgment, but artists eventually all have to find their own voice and their own way of working and no one can teach you that. In a way, we’re all self-taught.

LG: How did you get your start professionally as a painter?

Elizabeth Geiger: My first big show was at a community college in Charlottesville after my kids started preschool and from that, I was contacted by Callen McJunkin in Charleston, WV to show at her gallery. After several shows with Callen, I was asked in 2007 to be in a group show at Gross McCleaf Gallery. I’ve shown there ever since.

In college, I worked in a small cafe as a cook. I spent two years looking down at a table full of vegetables to chop, and that had an impact on me visually—especially being so close to the things, the intimate scale. For a long time, I wanted my paintings to give the viewer the feeling they were standing in my place in front of the table.

LG: Who or what would you say had the biggest impact on how you paint?

Elizabeth Geiger: My husband Phil has been a big influence on me as an artist, mainly by his work ethic. Slow, steady, and every day. I was always more like the hare—painting in fitful bursts then collapsing with burn out. Having two kids trained me to work more regularly and whenever I could, not just when I felt like it. When they were at school, I was painting. Aging has naturally led me to work regular, more reasonable hours. I’m too old to burn the candle at both ends.

It’s been amazing and daunting at times to see my husband’s paintings each day as they’re made. His initial block-ins are what I think of most—the broadest and abstraction that he starts with, the glowing light. I think what I appreciate most about his work, and what we both share as artists, is the sheer beauty of color. Ultimately, we’re both just trying to make beautiful and evocative images.

I took a winter Drawing Marathon with Graham Nickson at the New York Studio School in January 1991 after I graduated from college. I’d only been to New York once with a class trip, certainly never alone. I was definitely intimidated when I first arrived, I remember Graham being annoyed I didn’t have the right erasers or drawing board. But I was soon too engrossed in the process to worry about my lack of talent or training, I was just trying to survive being thrown in the deep end. I remember my hands bleeding from running my fingers over the staples holding the paper to the wall. I had never been in class with such serious students before. Once, Graham stood at the top of the stairs leading down into the room and said to us, “You’re getting LAZY! I think I’m going to be SICK!” Far from deflating me, I found Graham’s high standards and blunt criticism motivating. I left with new confidence in my drawing ability.

George Nick is another big influence. I met him at the Vermont Studio Center in 1993 and we became friends later. I’ve been fortunate to visit his studio numerous times and took his class at the University of Virginia in 2013. Like Graham Nickson, George has a strong personality and doesn’t mince words. His work ethic was something to see at UVA as he painted around the school, especially since he was 84. He goes for the jugular, no tiptoeing around. His colors remind me to go for it and not creep up to mine with hesitation. I like how his paintings of things—houses, cars, toys—are like portraits, painted with the same intensity and individuality. I want my work to have that quality, for my objects to have personality and evoke lives being led outside the painting.

LG: I understand you make a frequent practice of making paintings of reproductions of artist’s works that you admire. I assume you’re likely trying to simplify their work to the most essential aspects. What might those be for you and how long do you generally spend with a copy?

Elizabeth Geiger: I make small fast copies and occasionally larger ones. I mainly copy figurative and landscape paintings to get the essence of the rhythms, groupings, and proportions. The tonal structure. Ten years ago, I copied Claude Lorraine’s Landscape with Merchants at the National Gallery of Art in DC. I didn’t understand the painting, but I knew Claude was one of Cezanne’s favorite painters and I wanted to know why. After 10 weekly painting trips to DC, I was mesmerized. The luminosity, I discovered, came not from endless bold color, but from the tonality. The sky is bright because the trees are so dark. It took all 10 paint sessions to make the trees dark enough, almost black. I used to not believe the light in the old masterworks, things seemed so dark compared to modern painting – but now, every time I see early morning light raking behind a tree in dark shadow, I think of Claude and smile.”

I like making copies. Mostly fast—an hour or so with a palette knife—trying to focus on a particular aspect of the painting. Tone, composition, color, or light. I may want to make myself mix colors I’m not used to, or to absorb an unusual composition. Sometimes I make a copy of a painting I don’t understand to try and see how it works. Copying made me look beyond the modern and contemporary artists I looked at early on to artists from the past.

LG: You’ve said that you like to learn from your favorite painters by going further back into their lineage to learn more about their teachers and their teacher’s teachers painted, potentially seeing all the branches of art history as a family tree to gain insight from.

Elizabeth Geiger: The best advice I ever got was from Bernard Chaet who told me to “Go to the source!”, meaning, look at who the artist you admire was looking at. I have found this to be the best way to find my own voice as a painter. Staying with the most recent influences can make you a mimicker. Going back in time helps you understand work from recent history more deeply.

LG: I heard that you like to spend time when first starting a painting choosing and mixing 3 or 4 main colors in advance to help with establishing harmonic relationships. How much does the still life setup decide the colors you choose or is it more than the colors you want to use decide how you set up the still life?

Elizabeth Geiger: I set up still lifes in a number of ways, sometimes by accident, sometimes based on a painting, but always based on a color idea and shape groups. I use spotlights to create echoing shadow shapes and to highlight or obscure the objects themselves. I have a lot of tables and that’s where I start with the “stage”, then pick a group of objects and cloth, move them around, add lighting and look for a hierarchy of shapes and a sense of rhythm, repeating arcs or a fugue of rectangles or angles. I start painting small paintings on scraps of gessoed paper, sometimes black and white, then color.

I always use a viewfinder when setting up and starting a painting. It’s a type of drawing for me, looking for the divisions and where things line up…what is going to be on the outer edges of the painting. I’m often determining how big I want a central object—even if that’s a cloth—to be in relation to the rectangle. Or how much background I want vs. tabletop. Just like in a landscape, where I want the “horizon”.

Small oil studies help me examine a setup. If I’m not satisfied or challenged by it, I’ll change it—remove or add something, change the lighting, even rotate the table 90 degrees and paint it from that angle. I may alter my distance from the setup and make another study. When I’m in my groove, I’m open to changing anything at any time. This can lead to good results, but also to a lot of unfinished paintings in my “maybe” pile. It’s just how I work. Love to start paintings. Finishing is the tough part. Knowing when to stop… I’m still trying to figure that out. Graham Nickson told us, “Keep looking at your work like it’s the front of a building and if any windows are open, try and shut them. When you look at the building and don’t see any windows open, stop.”

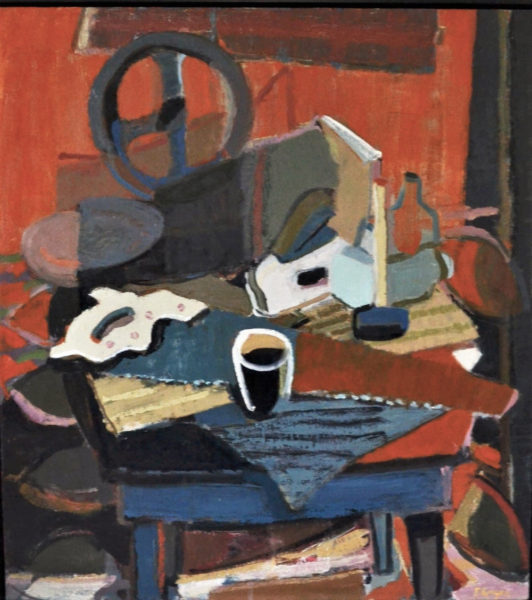

Deibenkorn said, “Use boredom to destroy”. If I lose interest in a painting, I need to break it open again and do something else. I think I lose interest in a painting when I’ve decided exactly how it should look at the end, so it no longer feels like experimenting and discovery but just cranking it out. George Nick once said to me, “People talk about overworking a painting. There’s no such thing! If it’s not working, you haven’t worked on it ENOUGH!” I’m always relieved when I give up and bust a painting back open—rearrange it…change the lighting…paint a glaze of color over it. That’s the moment where I like to be. I’m in it, not a spectator.

LG: Please tell us something about your considerations for mixing color.

Elizabeth Geiger: My paintings start with a color chord. This chord has predetermined, of course, because I set up the still life, but I don’t always know what the hierarchy of the colors will be. A colleague at Beverley Street Studio School says during critiques, “This is the Lucy Show. Where’s Lucy?” When I’m painting, I’m working out who’s the star and who are the supporting characters. Everyone can’t be Lucy. Someone has to be Ethel. And Ethel’s there to highlight how funny Lucy is. Otherwise, it’s confusing.

I’m slow and careful mixing this color chord because it determines the other colors. When 6 to 8 colors are making light or a color vibration I like, I start to think more about composition and setting the table and objects into the rectangle. I sometimes wish I was more narrow in my color and set up choices… it would make it easier. But I keep thinking of as many options as long as possible. Should the large pot in the back really be in front? Should I stand close to the table or across the room? Should I add more colored objects or remove them?

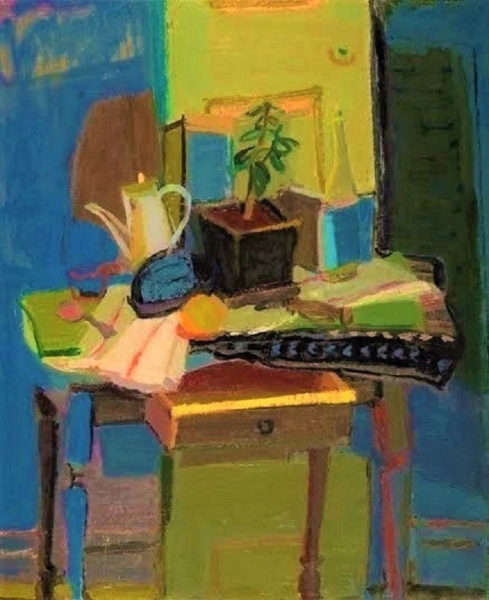

Once I’m ready to start painting, I think about how “real” I want the color to be, or if I want to use the “wrong” colors and give it a more imagined feeling. That’s what I did in my 2016 show at Gross McCleaf. I experimented in baby steps—making drawing after drawing or oil study after study, each a bit more distorted than the last until, as Braque said, “the original concept has been obliterated”. Until the painting surprised me.

I want to return to that process but with moving and my new studio, it will take me awhile. I have to digest this new place and understand it before I can play around with it. That’s why my recent show was different than the one before. I was still taking in this space so I wasn’t ready to experiment, just to simplify. People may think artists can just wake up and do whatever they want—careful drawing one minute, go crazy throwing paint around the next. But that’s not how it is for me, the older I get, the harder it is to shed old habits. It’s like turning the Titanic around. But I still try to do it.

LG: Is a limited palette important to you? What colors do you usually put out on your palette?

Elizabeth Geiger: My early palette was huge, 24 plus colors, 3 versions of each primary and secondary color, titanium white, earth colors, and black. My considerations then were more about getting the colors “right” so I needed all the colors I could to match what I saw. Now I use fewer colors because I have other balls in the air. Now it’s usually a double primary with a few earth tones, black and Utrecht white which is warmer than titanium. I’ve always thought I’d try more whites, especially lead, but never have. I do so much sanding, I don’t want the lead dust. I always sand outside with a mask and gloves on, using a block of wood wrapped in a piece of sandpaper, often sanding over a trash can. Then I gently brush the extra dust off the painting surface into the can. Inside, I vacuum the canvas with a canister vacuum on low.

LG: Are you thinking about the Charles Hawthorne large “color-spots” approach to painting?

Elizabeth Geiger: I definitely start paintings from Hawthorne’s color spot approach, glazing happens only if I’m stuck and unsatisfied. I may stumble if the paint’s dry, otherwise it’s wet into wet. Technical stuff tends not to be at the forefront of my mind. I’m thinking about composition, hierarchies of shape and tone, and the basic color. That’s all I can handle thinking about. I prefer varied surfaces with thick and thin paint, scraping and drawing in with the palette knife, but it works best if done unconsciously so I don’t think about it. I do scrape a lot after painting. If I don’t like it, it’s gone.

LG: Do you set goals for yourself as an artist- what would you say you aim for?Elizabeth Geiger: My goal as a painter is to keep painting. Bernard Chaet said to us at the Vermont Studio Center, “Painters only fail if they stop painting. Success is continuing to paint.”

Teaching for me is very stimulating for my own work which is why I do it. What I teach comes right out of my studio—my own work. I teach classes about what I’m dealing with myself. That keeps me more engaged. I’m a student in the class too. Whatever I tell the students to do, I do. I include my own work in critiques. Showing beats telling every time.

LG: So many people today are distracted by the crazy world as well as their phones and find it difficult to focus their attention on anything for long. Can painting help address this issue?

Elizabeth Geiger: The more technology we have in our lives, the more important and soul sustaining art is. Ultimately, painters need to love the practice of making paintings to keep themselves going to the studio, but artists also need to develop a philosophy of why art is important. Like it or not, Americans are pragmatic. Our society can have a “Yeah, it’s pretty, but what does it do?” attitude that’s not the same as other cultures whose public places can be decorative for the sheer beauty of it. Living in such a culture has forced me to actively think about why I believe art is not a luxury, but a necessity.

LG: A question I keep asking myself and often ask the people I interview is how can painting still be important and relevant in the midst of this pandemic with so many people dying, so much craziness, and all the other challenges that threaten society?

Elizabeth Geiger: I like to tell the story of a former neighbor in Charlottesville who’s a doctor and a serious art collector. He did a two-week rotation at St. Georges Medical School in the Caribbean when my sister was a student there. She called me after he gave a lecture to the entire class of 500. Apparently, he walked in and said “My name is Don Inness and I hope to teach you something in the next two weeks that could help you save a life someday. But first, let me show you why you should even bother.” Then he turned off the lights and gave a slideshow of his art collection… for an hour. So, a doctor is telling medical students that what we artists do is what’s important. WOW. As the daughter of a neurologist and sister of a surgeon, I always thought what THEY did was more important. But we artists need to remember that we’re preserving the culture. For me, art cuts through the everyday business of life and brings me to a more divine, timeless place. Good art slows us down. Technology speeds us up. I want to be on the side of the slow down.

The video above is a terrific recent “Art Chat” interview with Elizabeth Geiger

by Martha Gordan from the Winslow Art Center.

Geiger talks at length about her work, process and history.

Elizabeth Geiger will be teaching two 5 week Zoom classes this winter through the Beverley Street Studio School – Drawing the Still Life: Location Mark and Line Drawing, Fridays January 15 – February 12, 2021 and Painting with Compliments, Fridays February 19 – March 19

Hi Liz. A remarkable interview, and i like all your paintings very much. Good, strong color with a sense of joy and discipline. I like your talk about the moral force of painting in a time and place that values speed and a mediated experience. Great to read this. Wish I could see the work in person.

Enjoyed reading your interview with questions I wanted to ask my self. It’s interesting to see just how much color drives Liz’s excitement and expression. The mark and the color stand out and I’m particularly drawn to the paintings from this year with their paired down elements; shapes, color, and composition lending a sense of quiet.

This was very well done. I really learned from the clarity and detail in the painter’s responses to the questions. I have loved her paintings for some time (seen at the Gross McCleaf gallery), and this added to my understanding of her work. Thank you, Elizabeth Heller

Great interview, enjoyed seeing the studio. The show at Gross McCleaf is one of the few things I’ve gotten out to see and it was well worth it.

Ms Geiger : I was at Vermont Studio in 1993 and recal meeing you . The sesion included Bernard Chaet Wolf Kahn and Marjorie Portnow Several Chaetisms stuck with me from Mr Chaet . ” Gentle Kisses , No Grabbing ” was one that stuck with me . At the time I was doing large scale sem narrative landscapes . After I returned home I changed my approach with Mr Chaets ” Gentle Kisses No Grabbing ” Edict in mind and within 2 months i had entered a juied competition New Haven Paint And Clay Club ( Juried by Leonart Anderson ) and was selected by mr Anderson for one of his Jurors awards . Thank You Bernard Chaet . I recal being shocked when you told me you were married to Phillip Geiger !! So glad to see this expose on you and your work Congratulations . Andrew Korn

Hi Andrew – was that the October session? I just remember that EVERYONE was there for the fall colors and was a painting outside and I was inside and working from the model with Bernie’s wife and often no one else… By “Gentle Kisses, no grabbing” do he mean the touch on the canvas?

Thanks for reaching out and I will look for you online and on Instagram.

Best,

Liz

What a fantastic interview with Elizabeth!

Such rich and interesting paintings and the personal and sincere responses to the insightful questions which bring these beauties to life, thank you both!