I’m honored that Edmond Praybe agreed to this email interview and thank him greatly for being so generous with his time and attention in sharing his many thoughts about his art and process.

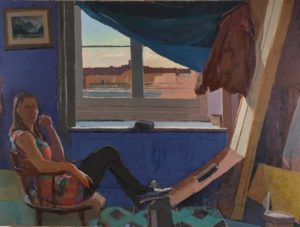

I’ve long admired Edmond Praybe’s paintings and the inventiveness that he brings to his compositions. I’m delighted by his blending of careful observation with abstraction and the astonishing rightness of color tone. Praybe simultaneously satisfies our cerebral need for pictorial surprise with the more visceral cravings for emotive visual poetics.

Edmond Praybe is a Maryland-based painter who shows at the First Street Gallery in NYC. received his BFA from Maryland Institute, College of Art in 2004 and MFA from the New York Studio School in 2012. Edmond’s work has been shown widely in juried and invitational exhibitions. His work has been featured at venues including Y:Art in Baltimore, MD, Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati, OH, Peterson Contemporary in Bend, OR, Stephen F. Austin State University in TX, The University of Mary Washington in VA, Prince Street and Bowery Galleries in New York City and The Mitchell Gallery at St. John’s College in Annapolis, MD. Notable art critics Jed Pearl and David Cohen have selected Praybe’s work for inclusion in exhibitions. He has been the recipient of the Hohenberg Travel Grant, two Mercedes Matter Awards and was a National Parks Artist-In-Residence at Catoctin Mountain Park.

More of Praybe’s work can be seen at edmondpraybe.com

Larry Groff: When did you know you wanted to be a painter?

Edmond Praybe: I knew I wanted to make art in some way from the time I was very young. As far back as I can remember, I always enjoyed drawing. It was something I started doing with my dad when I was very young. He liked to draw and I would try to draw along with him and copy what he did. Eventually, I started doing more on my own, mostly copying from cartoon stills, comic books, illustrations, and advertisements. Once I got into high school, I thought I would go to art school and probably pursue illustration or graphic design. I painted some in high school and began working more from direct observation. However, it wasn’t until my first painting class in college that I realized I wanted to make paintings and drawings as fine art rather than working in a more commercial form.

LG: What was your experience during art school?

Edmond Praybe: It quite literally changed my life! As an undergrad at MICA, I not only decided that I would be a painter, but I also learned all the practical foundations of how to construct a painting. I also learned how essential it is to understand drawing to make solid paintings. I came to see that even if you are a painter who rarely draws as their practice, fundamental knowledge of drawing is essential for making strong paintings. This is an idea that came up again as I studied for my MFA at NYSS. Drawing is the lynchpin of teaching at the Studio School and I learned a more advanced way of analyzing and expressing the abstraction of space into a 2-dimensional drawing while in that program.

During both undergrad and graduate school, I did a huge amount of work. I tried many different approaches, painting and drawing media and subjects (figure, landscape, still life, narrative, abstract). It was a place to experiment, receive feedback and ultimately figure out what worked best for me. Even the not-so-nice critiques and comments were constructive- either for pointing out a valid failing in my work or knowing when I needed to stick up for what was important to me instead of trying to please someone else. I had some great teachers in high school who gave me a solid grounding in painting and drawing techniques, but the time and space available to me in art school blew things open in terms of possibilities.

LG: What were some of the most valuable lessons you learned in art school? What was the least useful?

Edmond Praybe: Throughout my art school experience as a whole, there were not a ton of demonstrations from faculty- this is how you mix this color, this is how you make this kind of brushstroke, here’s a technique for all prima, etc. I mean, there was a little of that in the foundation year, but most of the instruction was based more on prompts or concepts. There would be a lesson on value or shape or color relationships with explanations and some book or slide examples. Then we would be free to explore that idea in the classroom/studio, watching the other students and getting feedback as the instructor made their way around the room. Critiques were the main format for learning and analyzing those lessons. I learned so much from the critiques of my work and the critiques of my peers. What I’ve come to appreciate about this approach (especially as I’ve been teaching more myself lately) is that it prevents that urge of the student to paint ‘like’ the instructor. This also helps them interpret these fundamental ideas that weave their way through most successful paintings no matter what the style, mode, motif, etc.

LG: Did you ever feel the need to rebel against what you learned in school to find your own voice?

Edmond Praybe: I don’t feel like I ever had to rebel against what I learned exactly. It was more of a process of figuring out what some of the lessons and concepts meant to me in a personal and meaningful way.

There was a period after grad school where I was still trying to make sense of everything I soaked up. It was such an immersive period entirely focused on talking about and making paintings and drawings. At that point, the work responded more to what I learned and less about who I was, less about my life and interests beyond the studio. I think anyone who goes through rigorous training in the arts feels this way, and I’m sure it extends into other fields of study.

I was making paintings that were very stripped down. I wanted to get to the bare bone essentials of everything. I was determined that nothing would be included purely for the sake of displaying facility or describing something in an overtly illustrative manner. The paintings were still based on representation, but all elements were distilled into relatively flat shapes, with little modulation of tone or color within those distinct shapes. They were often based on drawings so that I had less information to be tempted to describe.

I learned so much about what I could take out of a painting and still convey a sense of the original motif, scene, or form. And I learned how important an understanding of the relationships of the large color masses is to create a successful image. Still, they seemed more like exercises than statements of my own beliefs, ideas, or interests (painting related or otherwise). Then I eventually started adding things back into the paintings as well as painting more from direct observation.

It started to feel like the more I put back into the world of the paintings, the more I saw myself in them. The problems of resolving the paintings became more personal and challenging. The ideas and solutions were no longer strictly based on things I’ve seen other artists do or broader lessons from school. It sounds super cheesy, but the best way to rebel is to be yourself. No one else has the same interests, influences, and abilities as you.

LG: After you finished your graduate program at the New York Studio School in 2012, you received the Hohenberg Travel Scholarship and were able to spend time in Europe studying paintings in Italy, Amsterdam, and England. Please tell us something about what that was like and what that meant for you.

Edmond Praybe: It was a huge gift for me to study from paintings in Europe post-graduation. This was one of those rare moments in life where I felt like I could have it all. Before applying to grad school, I had seriously considered a painting tour of Europe but opted to focus my time, energy, and (importantly) limited finances towards a graduate program. When I won the Hohenberg Scholarship, I couldn’t believe it- I got to do both! On top of this, I was fortunate enough to sell a few works from my thesis show, which allowed my wife to join me.

Seeing the great Italian frescoes in situ was a particular highlight. The Piero della Francesca’s in Arezzo and the Giotto’s in Padua along with the beautiful Masaccio’s at the Brancacci Chapel in Florence made an enormous impression on me, both instantaneously in person and slowly unfolding in my memories through to the present. The balance between careful planning, established patterns of figuration, and new innovative approaches to narrative subjects, forms within a space, and geometry made for such unbelievably timeless images.

The Rembrandt’s at the Rijksmuseum was also a joy to see. His late self-portrait as St. Paul had haunted me since I discovered it in reproduction as a teenager. The mass of that head as it emerges from the dark ground and the transformation of the paint into flesh and the folds in the turban are pure magic to see in the flesh.

We spent a good bit of time roaming the National Gallery in London as well. I was able to draw from Titian, Rubens, and Piero while there.

Oddly enough, I was transcribing from almost exclusively figure paintings in museums and churches, but when working from life, I was mostly drawing from the landscape. Of course, I was doing the requisite quick figure sketches on the streets, train stations, and airports, but the things I was doing that felt the most solid and related to the paintings I was studying were the landscapes. They were whole integrated worlds but taken from direct observation rather than constructed in the manner of the old masters.

LG: Have you been able to paint full-time since then?

Edmond Praybe: No, I worked full time in an unrelated field until about two years ago. I also began teaching as an adjunct a few years after grad school. I never saw myself as a teacher, but I’ve enjoyed it from the very beginning. Not only is it great to watch the students develop over a semester (or longer), but it helps me organize my thoughts on what is essential about specific issues of painting and drawing.

Gradually, with a mix of teaching income and sales of work, I quit my day job to focus on teaching and painting full time. I consider myself lucky to work with various great organizations that allow me to teach classes and workshops carte blanch more or less.

LG: I understand that you teach workshops. How did the pandemic affect you concerning this? Did you teach online workshops? If so, how did that go? When is your next workshop?

Edmond Praybe: Yes, I teach classes and workshops regularly at several colleges and art schools. Like many artists, until the pandemic, I had only taught in-person studio classes. However, after overcoming some initial hesitations, I have been teaching online for the last year and a half. Like so many of my artists’ friends, I had concerns about how effective it would be to teach painting in an online format. After some trial and error and discussions with others working out similar issues, I’ve come to embrace the advantages of working online. I’ve had to adjust my instructional style to focus more on various demonstrations and moved the large portion of my critiques to message board interactions with live feedback during Zoom sessions when necessary. I’m big on using slide shows to cite how other artists have approached my course topics, and the online format has made that incredibly convenient. Certain things like perceptual color and that tactile experience of painting alongside a group is harder to replicate, but overall the classes have been going very well. Of course, there is the added advantage of reaching more people around the world without the complications of travel and related expenses.

It seems that all the schools I work with are planning on integrating online offerings into their regular program, even once things get back to business as usual. As long as the goal remains to keep the bar high for both students and instructors, this is good for everyone involved. It increases the reach of certain artists and organizations while facilitating quality instruction more inclusively. I do miss being in the classroom and working with students in a real space. Fortunately, I’ve had the opportunity (and have a few more coming up) to do some in-person teaching safely.

LG: What artists or art has been most significant to you, and how you paint today?

Edmond Praybe: I think it still comes down to many of my teachers. I’m very aware of how my past teachers affect the way I see and approach my work and that of other contemporary and past painters. It’s not only those teachers themselves but also the work they loved and how their passion for it became infectious and spread to us students. For example, I’ve developed a deep love for Bonnard and Matisse that I cannot imagine would be as intense if not for how Graham Nickson spoke about them. I’m sure Graham and I grab ahold of different aspects of their work, but I imagine that that gut reaction to it is much the same. Not to mention that Graham’s work continues to inspire me and reminds me to ask tough questions with a level of honesty (to myself more than anyone) and integrity.

Stanley Lewis, Mark Karnes, Sangram Majumdar, and Carl Plansky all strongly influenced me and my development as a painter. One huge thing that I got in some form from all of them was this idea of not being dismissive of different work. It sounds like a no-brainer to anyone that’s been at it for a while, but understanding the broader world of ideas and approaches toward painting and art, in general, is only going to improve your work- and probably make you a better and more open-minded person in general. It’s very easy to get sucked down a narrow tunnel of thinking and write off those whom you see as having divergent goals. But more often than not, work created in this kind of vacuum does not resonate or feel complete.

I remember Mark Karnes showing slides of Frank Auerbach and Carl Plansky talking about Veronese as we transcribed his Deposition vividly as an undergrad. These pairings seemed so surprising to me then. I couldn’t fully comprehend one being influenced by the other in both cases until I heard their take on the work. This idea goes beyond just painters looking at other seemingly dissimilar painters. It has to do with being receptive to conceptual works, whole other art forms, and the greater world we live in. Beyond any technical, formal or aesthetic training, the idea of keeping your mind and eye open as well as finding bits of yourself in (or through) the work of others became paramount. It’s a kind of holistic approach towards painting, both overall as a practice and as a sense of unity within a singular work.

LG: How central is observation to the creation of your work?

Edmond Praybe: Observation is crucial to what I paint. I often tell people I just don’t have enough of an imagination to make things up. And I’m not kidding. I’ve tried! I’m concerned with all the abstract issues of painting whether it be shape, color, structure, etc. I can’t seem to make sense of them without a framework of observation to hang those concerns. I get much more surprising results working from observation. I’m not especially interested in painting what I already know. I want to discover something new each time, even if that something is a tiny part of the painting, like an exciting color relationship or part of a compositional arrangement I wouldn’t anticipate working, but it does. My paintings, particularly the still lifes, start with some idea: what happens if I build on this shape against that negative space? Can I create a situation that recreates a certain mood? What does silence next to chaos look or feel like? Then I set up something that I feel responds to that idea and begin to paint it. Sometimes the painting carries that initial idea through to the end. Other times the painting demands a new direction as it unfolds. I let the situation that I’m observing guide the process to a certain point instead of continuing to impose that idea on it if it’s not coming through.

LG: How much do memory and invention play a role?

Edmond Praybe: As much as I’m concerned with observation, there are places in all of my paintings where that simply is not enough on its own. Values and colors must be adjusted, details in one section must be suppressed while embellished in another area, and compositional lines must be emphasized and reinforced. Invention on a formal level plays a big role in those decisions. I’m not making up things per se, but I’m unifying what I’m observing by stressing or sometimes exaggerating specific relationships in the painting.

Memory is a little more tricky. It comes into play to varying degrees. We’ve probably all heard it said that as soon as you take your eye off of the subject and move it to the palette and the canvas, you are working from memory, which of course is true, but that’s not how I would classify the major role of memory in my work. I may build a painting off of a color combination from a particular memory. I’ve done some with a primary color chord taken from how I filtered memories of certain Italian frescoes or a white-centered palette from old black and white family photos. I also include living elements such as plants, flowers, and figures in my work, which move change and slowly (or sometimes rapidly) decay as the painting moves forward.

In those cases, I have to either make do with the information I have gathered from previous sessions, change the painting based on the current state of the object or use my memory to develop things further. I also occasionally use fleeting raking light in portions of a painting and continue to work on those sections once the light has moved, relying on my memory of those values, shapes, and colors.

Most of these examples are much more ‘present’ forms of memory than most people might think of, but it still keeps things a step removed from a strict sense of direct observation. I think this allows for a select amount of distillation to occur from observation to response.

LG: Your recent work seems predominantly still lifes or still lifes with the figure; previously, you seemed to make more landscapes and figure paintings. Why did you change?

Edmond Praybe: Some questions kept coming up from painting to painting that I felt could only really be explored with a more controlled subject. This has led to more still lifes over the landscape and figure paintings. I like the option to set up specific ideas in still life and be in complete control of the arrangement. I can explore any formal issues using direct observation of the still life as a springboard. I’m able to find a middle ground between observation and abstraction in still lifes. It is like setting up an abstract painting with real objects and working through those relationships using the clues in front of me.

Not only that, the objects themselves have specific meanings to me and hold certain memories. They may not create a cohesive narrative, but the arrangements are all made up of my items collected over many years. In a way, the objects become like figure assemblies when the arrangement comes together. I think of them as being more related to the history of multi-figure painting compositions (without the narrative part) than to still life as a genre.

I still very much enjoy painting all three motifs. Still, the practical complications of both the figure and landscape make them much more daunting to work with observationally. Figures move, the clothes and hair are never the same from session to session, scheduling time to have someone sit for you, changing weather, seasons and all the other discomforts of plein air work make it difficult to sustain long enough for me to say what I feel I need to in a painting. As much as I embrace the idea of change in my work, there is a point at which the entire process can become only about change. In that case, hard-wrought relationships of color, value, composition, mark or whatever become lost to a constant game of reinvention.

LG: Tell us something about what goes into your setting up a still life.

Edmond Praybe: I usually start with one simple idea. It could be a color idea: maybe I’ve seen something that makes me want to explore a painting of almost entirely red, or I’m drawn to a color combination that I’ve seen in another painting or somewhere in nature. It could be a compositional arrangement I’ve never attempted: I recently tried a still life where one section contained a huge variety of saturated colors, and another section was entirely subtle tones of white.

The challenge was trying to make those two zones work together in a single image. I could start with a range of scale in the objects that I find interesting: something large, voluminous, and clunky down to small, delicate, and linear things. It could even be as simple as one object catching my eye in a way that makes me feel like I have to paint it, and the rest of the still life evolves based on relationships to that single object. Occasionally I’ll begin with the idea of a vague narrative. This is especially true for the still lifes involving identifiable pieces of clothing, which become kind of stand-ins for the figure.

LG: Anything interesting you can tell us about your working method?

Edmond Praybe: Probably the most interesting thing is that I have no set process. At least it’s interesting to me. It keeps me engaged in the work and asking the questions that push the paintings to an exciting place, hopefully. Sometimes I begin with a very detailed under-drawing, followed by a simplified color scheme block-in. The picture becomes more and more nuanced in terms of color and detail, followed by periods of editing, simplification, and then re-complication. Other times I’ll jump right into a painting with no under-drawing of any real compositional idea focusing on issues of color or value relationships. This will then be followed by drawing back into the painting to correct issues of proportion, scale, placement, overall composition, etc.

The two constants to my working methods are that I pre-mix color on the palette before each painting session and that I allow a change in both the painting and the still life setups or my viewpoint in a landscape, if necessary to the painting. I also tend to scrape and run sandpaper through wet portions of my work to unify sections when needed.

LG: Would you ever set up a still life and then photograph it and work from the photo?

Edmond Praybe: I’ve tried using photo references, but they usually do not work for me. On the rare occasions that I use photos, it’s more for the landscape as a reminder of color or certain patterns of value caused by fleeting light than anything else.

I have no moral objection to using photos or take any stance on a work’s authenticity if it is photo-based. There are many painters making very powerful work using photos in some way or another. It has just never really worked for me. It makes me feel too removed, not exactly emotionally or anything like that, but physically. There’s never enough in a photo for me- the tactile qualities of the forms, their surface, the nuances of color, and the beautiful distortions that occur when your head and eye move are all absent.

My still-life paintings are all a combination of direct observation and working through the painting on its own as a series of abstract relationships. Although still-life is the most static of all the traditional genres, so much change occurs when approaching it again and again from life. The ‘sameness’ of a photo puts me at a loss about continuing a painting in progress.

LG: Many of your paintings compress the space and look down on an arrangement. Why is this important to you? Do you use a viewfinder to find your selection?

Edmond Praybe: I don’t use a viewfinder, but I will tape off the edges of the still life to remind me of the boundaries of my composition. I usually do this after I’m a few sessions into a piece and have a better idea of the painting’s borders.

Working on the floor, looking down at a sometimes very shallow compressed space is the result of a pretty practical problem. I have never been interested in making paintings that are wholly descriptive of ‘an object’ in ‘a space’, of course, I’m very much invested in that as part of the paintings, but I’m more concerned with the overall organization/design/composition of the painting. In this sense working in a shallow space across a single plane allows me to arrange an abstract painting with real still life elements. I’ve never felt at home as a purely abstract painter or a purely representational one (although some may argue that I am relatively traditional). I need some combination of both, and this allows me to compose abstractly with form, color, shape, etc., while also giving me those tangible things on which to hang those formal investigations. Of course, as soon as I start to translate the still life arrangement into paint, it becomes evident that certain areas do not work for the painting. The motif’s adaptability means I can easily change something in the setup to suit better what I need in the painting. It’s a constant back and forth of rearranging the still life and reworking the painting, both existing in a somewhat shallow arrangement on a flat surface.

LG: How much time do you spend on arranging the items? Once you set it all up will you further change the setup as the painting evolves?

Edmond Praybe: I might spend anywhere from several hours to several days off and on setting up a still life. I tell people it’s usually at the very least a half-day process. It’s never really finished and continues to develop and change as the painting goes on.

As we were working on a still life in Carl Plansky’s class, he said, if something’s not working in a still-life, take it out. This suggestion is a practical solution to the problem. It relates to painting overall; if something is not working, change it. Don’t bash that same line, same color, same shape into the ground, using the same way–thinking it’s going to work this time. Maybe I’ll take something out or move it around only to put it back where it was when I started, but it becomes richer, fresher, and more vital for all that inching into place.

LG: Do you ever allow randomness to be a factor in the composition – like throwing a bunch of items on the floor until you find a compelling arrangement by chance?

Edmond Praybe: Occasionally, I’ll let parts of the still life be determined by a kind of chance. I include a lot of dried flowers, plants, bones and things like that into the setups, and I’ll let them land in casual piles or clusters sometimes. For the most part, the arrangements are highly staged to maximize the shape and color relationships, compositional flow, and tight groupings against larger forms or open areas.

LG: Edwin Dickinson would sometimes paint looking down on still lifes set up on the floor with a figure. Curious if his work has been an influence in some way?

Edmond Praybe: It’s odd, I’m a huge Dickinson fan, but when I started with these floor arrangements, his work never consciously came to mind. I do not doubt that it was there in the back of my mind as I was making the paintings, but this viewpoint came about as a solution to flatness/space and figure/ground relationships.

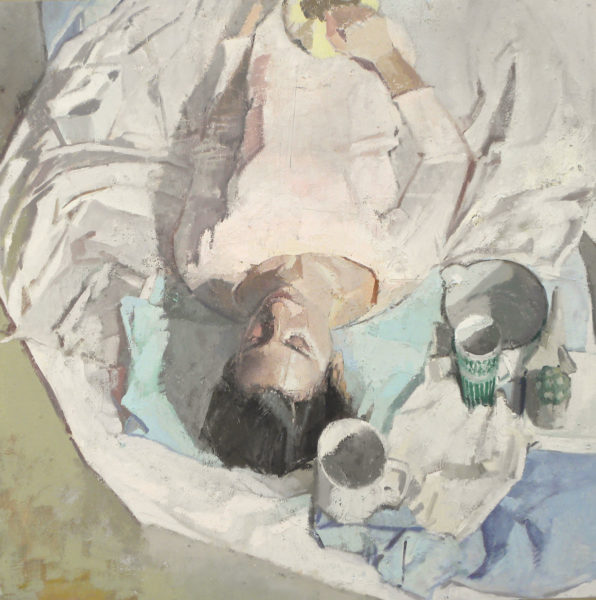

I did this painting of my wife a few years ago where she is lying on the ground with objects set off to the side of her head, and she is upside down.

And all the painters that I knew who saw it said–’Dickinson!’ That’s when I realized how he seeped in subconsciously. When I was making the painting, I asked, ‘how do I paint a figure in a still life and not have her break the entire image’s unity?’ My solution was to place her on the floor with everything else with her head pointing downwards in the painting.

I’ve made a series of paintings with a similar palette, all in subtle tones and temperatures of white.

Here too, I’m sure I was channeling something of Dickinson’s limited color tonal works. But again, the inspiration was more about a direct solution to something happening in my work. This was about balancing the simple beauty of drawing with all the complications of color. How do I make the line feel essential in a painting instead of simply decoration on top of color and value? Sucking out extremes of color helped me find a middle ground between painting and drawing. I actually began drawing with a pencil directly into the paintings around this time as well.

All of this is not to say that I don’t make work inspired by other artists or their takes on certain problems. I do that all the time. I’m constantly looking at other people’s paintings both to see how they address ideas differently and for the pure joy of looking and experiencing them.

LG: Dickinson and Charles Hawthorne promoted the color spot and color-tone approach to painting and to keep the painting open as long as possible. I’m curious to know in what ways this may have influenced your work on some level?

Edmond Praybe: I love this idea. I often start a painting with no drawing, not even those compositional strikes that Dickinson talked about, just color and value against color and value. It’s a tremendous way to keep the painting open. I’m not thinking about what a certain thing is or exactly its shape, just its rough mass, placement, and relation to the other masses near it. After I do this for a session or two, I’ll start to focus on the drawing aspects, correcting proportions, shapes, and overall compositional lines. If the painting closes down too much as it goes on I’ll go back to that color spot way of thinking and rework it, rip it open again.

Alternatively, I’ll start a piece with a very tight under-drawing in pencil directly on the linen panel, but I’ll block it in very loosely; coloring outside of the lines is what I call it. I can still see the drawing underneath, but I don’t let it stifle the paint mark or my color/tonal relationships. I love that dichotomy of tight and loose, color and line, seeing how I can make them all fit together in a cohesive painting. It is essential to keep the painting open through the process. Once things become too defined, the painting ceases to breathe, and I lose interest. I have to find ways of splitting it back open to that state of constant searching. It’s not exactly how Hawthorne and Dickinson thought about it, but I think it’s not too far off. The more precise you try to be from the beginning, the more inaccurate and distorted the painting.

LG: In what ways have your paintings changed over the years? Any predictions where your work will lead you?

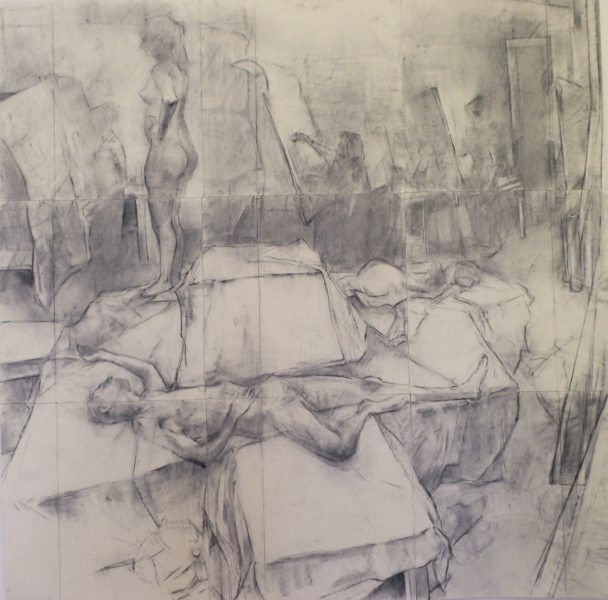

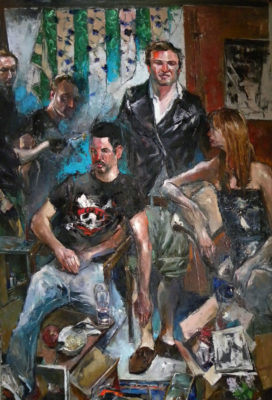

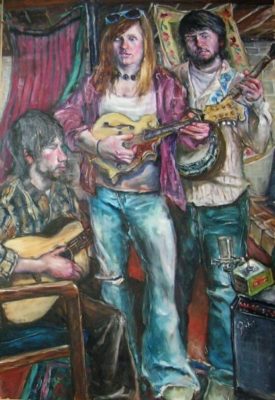

Edmond Praybe: I started out as a figure painter from my time in undergrad (2000-2004) and continued this focus in my studio and through graduate school (2010-12). The written component of my graduate thesis was all about figure painting and its relevance through history to the modern era. I assumed I would always make paintings largely based on the figure, and I still do (see image 30 in progress), but they tend to take longer, and I make less of them overall. Just within the figurative work, there has been a substantial change. When I started painting after college, I made large, on average 6′ tall, multi-figure paintings, sometimes based on a narrative.

I was somehow able to convince many of my friends to pose for these works. They were pieced together from separate model sittings and usually placed into a different environment, either painted from observation of a mix of drawing and color studies. I wanted to try my hand at the grand tradition of narrative painting. I thought that was how to show ambition- that’s how you make a statement. The paint surface and handling was thick and loose but still very descriptive, to a fault many times. The paintings had higher contrast with punctuations of highly saturated color.

A funny aside- A few of these paintings contained fairly aggressive life-sized full-frontal male nudity. I somehow managed to get one of these pieces into a group show at an all-women’s Catholic university. A large portion of the faculty there are nuns, and I was told that particular painting made an impression…

Eventually, the scenes started to contained fewer figures and the environment began to play a bigger role in the paintings.

Rather than sculptures on a stage, where the space is largely a product of the relationships of the figures, they became more about the figure’s scale, place, and relationship to the environment. The paint handling too became more controlled, there was more editing of superfluous detail, and the idea of larger shapes holding the painting together took precedent. This kind of synthesis and simplification was at its peak toward the end of graduate school and for several years after.

After moving back to Maryland from New York City about 9 years ago, I became more interested in landscape. I was still painting the figure often, always friends and family, and I incorporated them into the landscape paintings. I’ve always felt that landscape is the most difficult of the traditional genres, and I waited for the longest to try to tackle it.

I developed a greater interest in the complexities of composition from doing the landscapes, which led me to more still life paintings. I could now set up any imaginable complicated composition or color idea. This is the mode of thinking I’m still in. I’m trying to balance that formal interest with the more human response to the motif, the light, and the total experience.

I dabble in non-representational works, but I feel like I have never made anything worth talking about in that realm. I’m sure I’ll keep trying, though. It’s hard to predict where the work might go. One painting leads to the next. Sometimes I follow along, and sometimes I set the pace.

Blue Coat, oil on panel, 48 x 36 inches, 2018

LG: Some painters feel it is essential to have a signature style, a manner of painting that readily identifies the work as a unique voice. Other painters worry that consciously creating a noticeable style is less authentic and appears mannered. What might be your thoughts on this topic?

Edmond Praybe: What people think of as style, if it’s arrived at authentically, is the result of the artist’s most pressing concerns embodied in some form. As an artist’s interests become more specific, the sense of a signature style becomes more pronounced. For most mature painters, the work’s ‘style’ or ‘look’ varies from individual pieces and across periods based on their current dominant interests. Artists synthesize their schooling, influences, and immediate interests into something that becomes unique and readily identifiable over time.

Inauthentic style is largely the result of copying the look of someone else’s work without understanding its underlying importance. This can sometimes include copying yourself after a while if you’re not careful. Making a painting and then covering it with tick marks so that it looks like a certain school of painting is what I would consider inauthentic style and a sensitive observer can easily pick up on that. But if those marks are integral to the artist’s understanding of proportion, form, construction, etc., and they are present in the finished work then the style is bound to the process and feels truthful. The same is true for any number of approaches: thick paint, very thin paint, reliance on certain colors, reliance on a type of brushstroke or mark, etc.

When I think about style, I often think about Picasso. He worked his way through almost every mode and period of painting, conceivable even inventing new idioms, but his work always managed to look like Picasso. If you are honest with yourself about what you’re searching for in your work a sense of your personality can’t help but come through. Otherwise, it’s just branding, and I think we come to painting to get away from those sorts of things. When the style is good, it comes from having a sincere interaction with the object they are making. In an ideal world, all thoughts about a market, recognition, or even consistency are not present during that process.

LG: Where can we see your work? Any shows lined up for the near future?

Edmond Praybe: I have two paintings in the group show ‘Memento Vivere’ at Lyme Academy of Fine Arts. The show will run from October 17- December, 10th, 2021 in Lyme, Connecticut.

I also currently have several paintings at Peterson Contemporary Art in Bend, OR.

Very strong work. Honest and direct discussion of the issues of perceptual painting. I enjoyed the description of the painting approach and methods, and the comparison w the early figure paintings. Elegant and nuanced touch, tone, edge and seeing.

Thank you Edmond and Larry for this extremely thoughtful question and answer interaction regarding Edmond’s work and his process. The paintings are beautiful, interesting and very inventive. So much food for thought for the reader here!

beautiful work