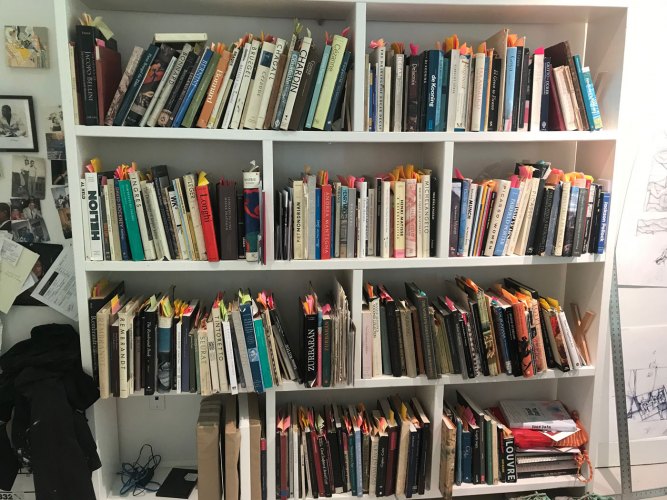

This past summer I met Deborah Kahn in her home in Amherst, Mass. The walk to her studio through her house went past a huge collection of paintings by many stellar artists, all competing for my attention. Once inside her studio, I was additionally overstimulated by her enormous collection of art books of every type, many with brightly colored post-it notes protruding as bookmarks. After calming down a bit and better able to focus, her paintings began to reveal the many conversations with the artists in those bookmarks. Her pictorial investigations of rhythmic interactions between the simplified figures, animal shapes and compressed color space of abstracted color shapes showed exquisite orchestrations of color harmonies. I was especially captivated by the tactile surface qualities of her work, something the online jpegs usually fail to properly show. Our conversation continued by phone along with further edits to the writing. I would like to thank Deborah Kahn for her generosity in giving so much of her time and attention to this interview.

Deborah Kahn was a recipient of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship. Kahn exhibits her work at the Bowery Gallery in New York City, Gross McCleaf Gallery in Philadelphia and at Les Yeux du Monde in Charlottesville, VA. Her exhibitions include solo shows at the Kittredge Gallery, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA; Wright State University, Dayton, OH; The Taft School, Watertown, CT; Augusta State University, Augusta, GA; Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, and the Washington Studio School, Washington, D.C. She has been in numerous group exhibitions, including at the Albright Knox Museum in Buffalo, NY, and the Toyota Municipal Museum in Nagoya, Japan. Her work has been reviewed in the Washington Post, The Hartford Courant, The Philadelphia Inquirer and Art in America. Kahn and her husband reside in Amherst, Massachusetts.

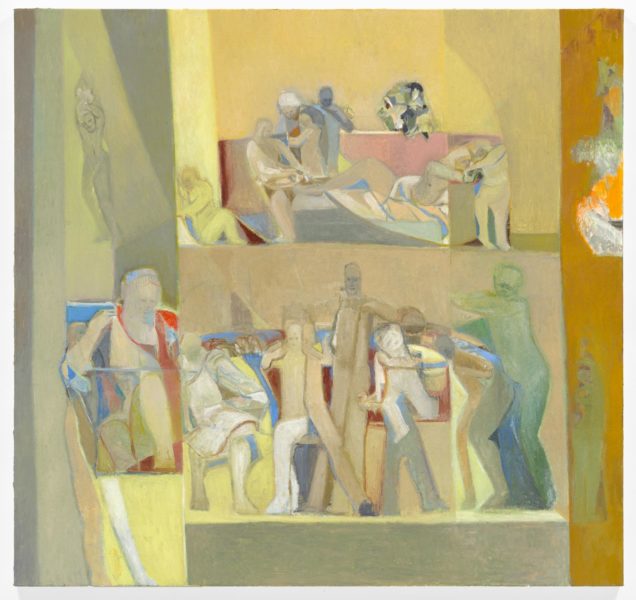

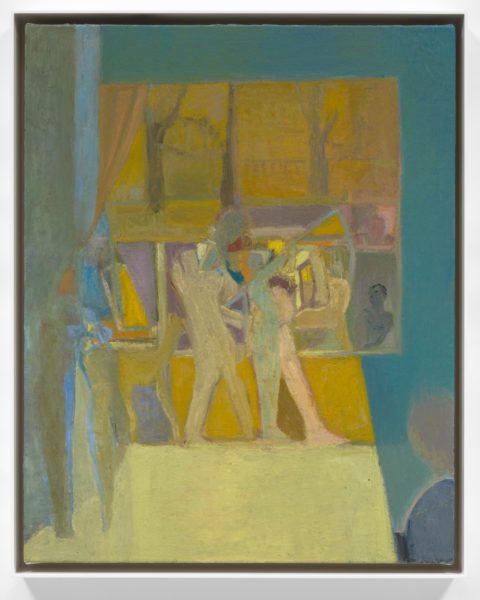

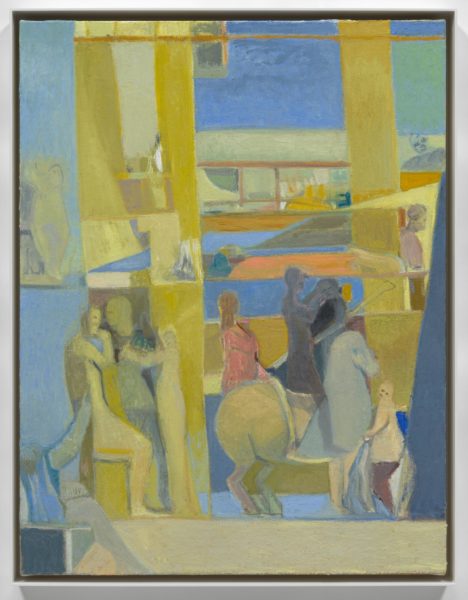

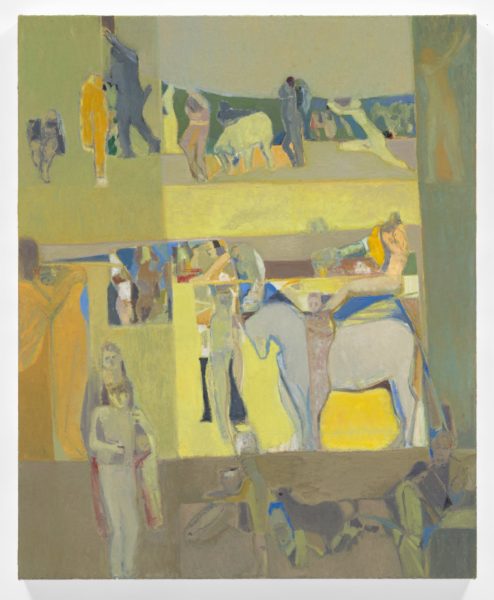

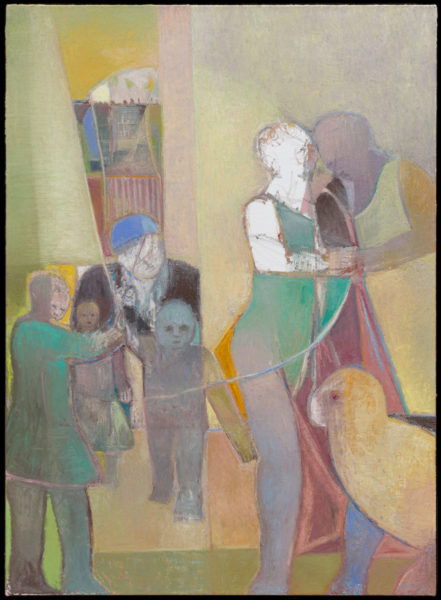

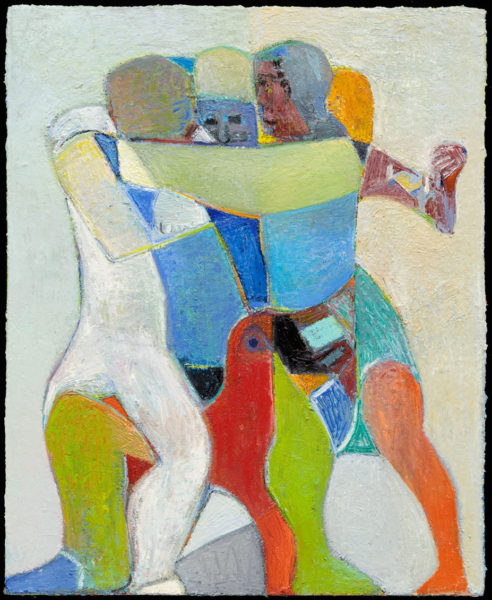

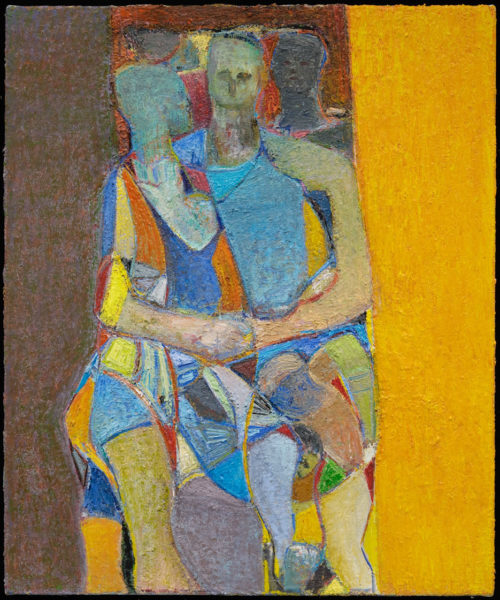

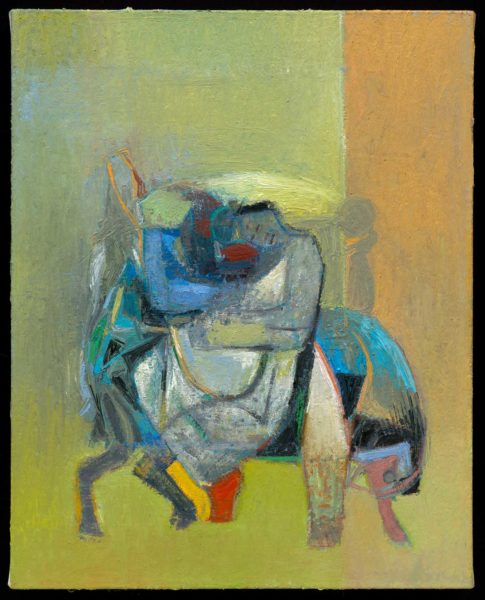

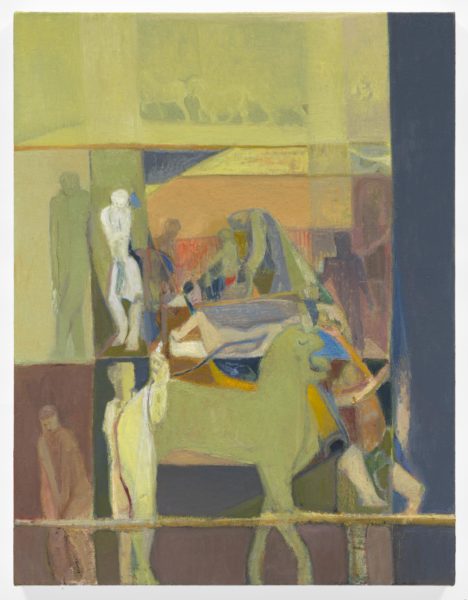

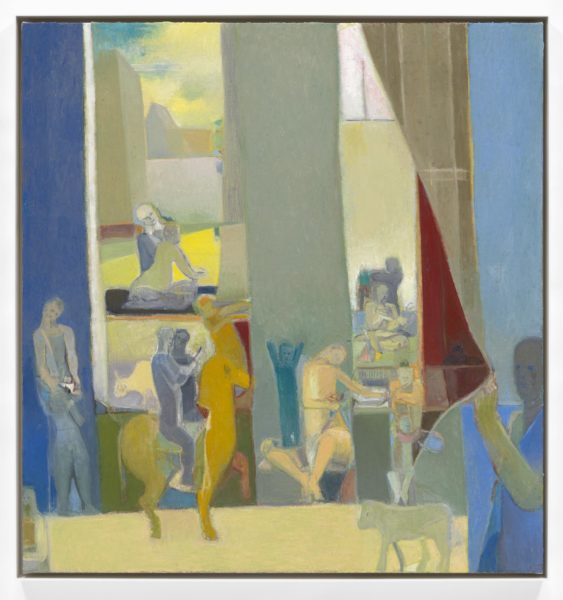

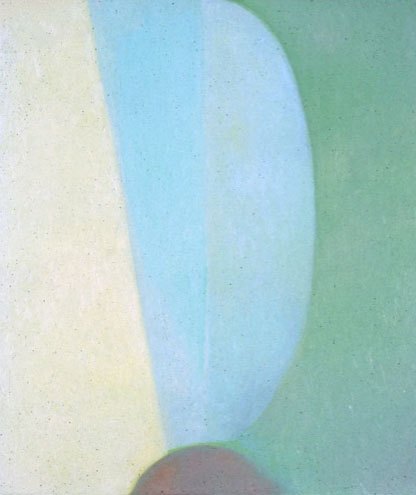

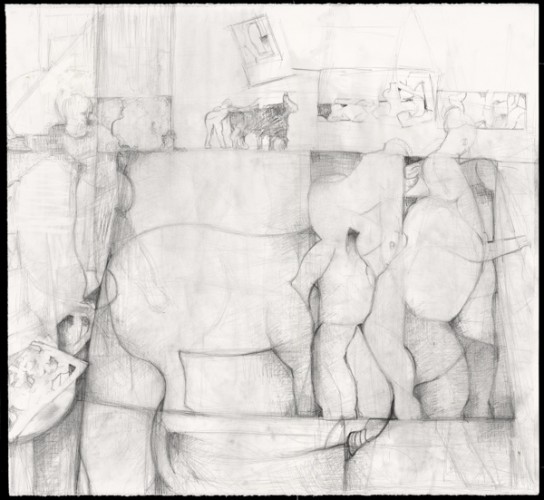

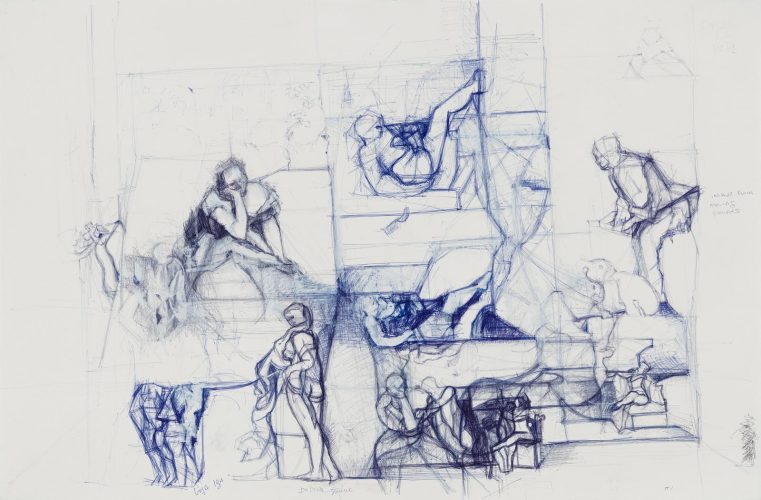

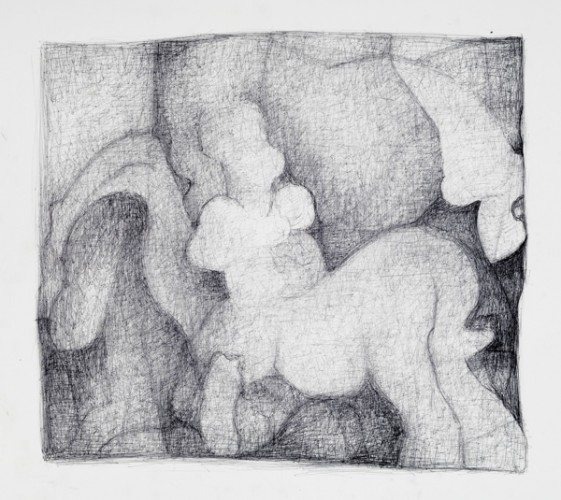

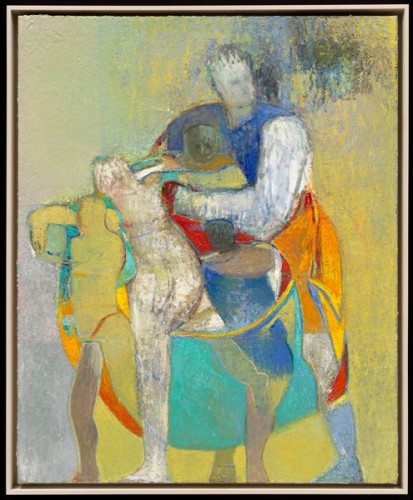

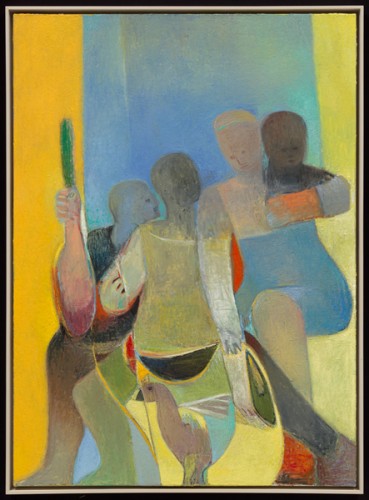

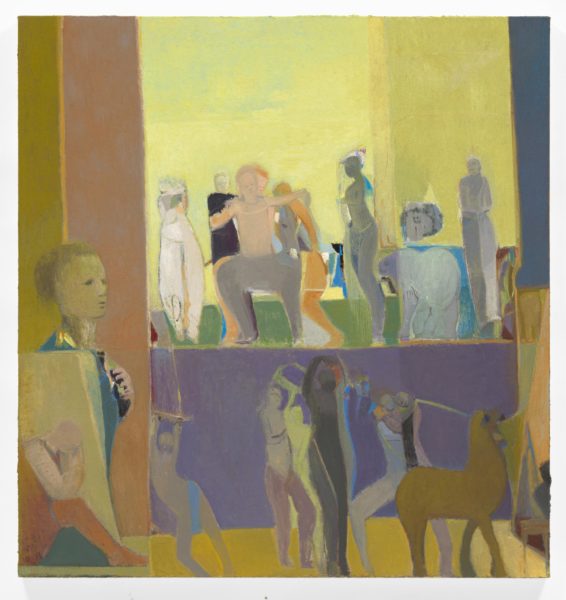

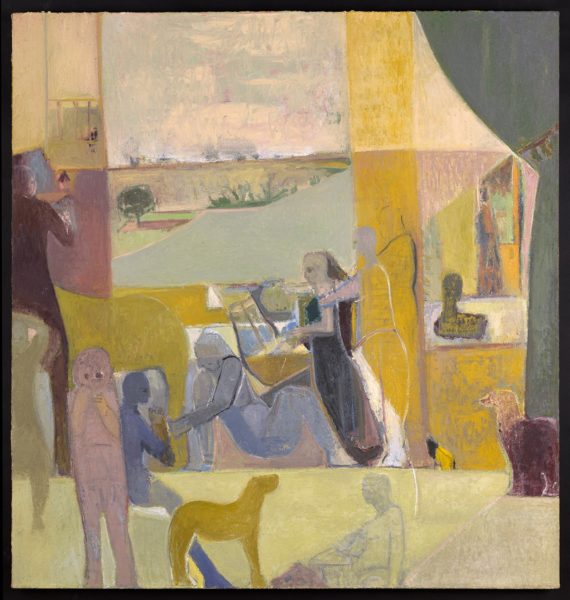

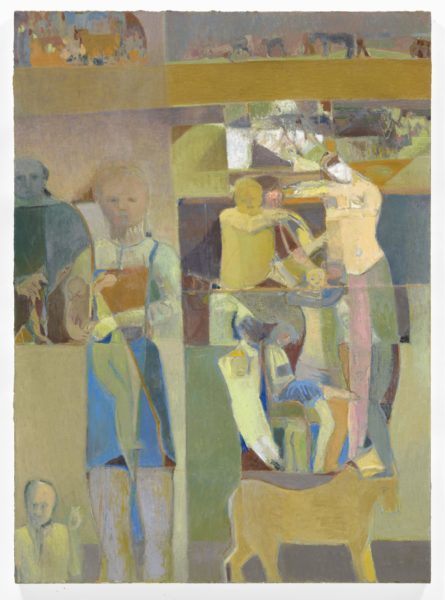

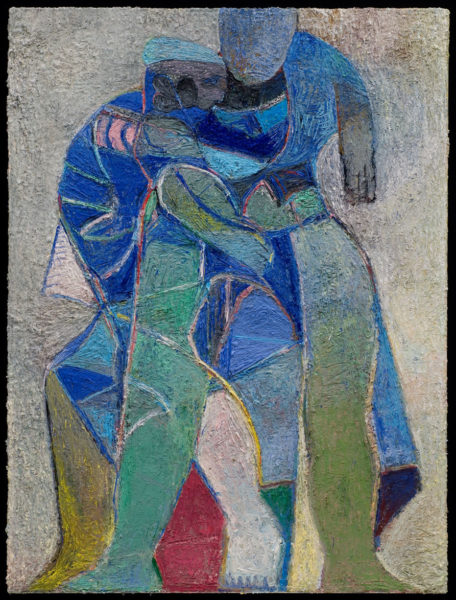

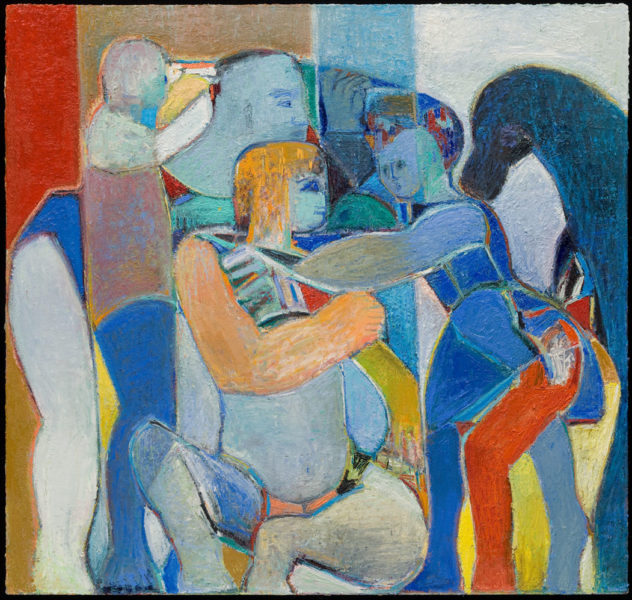

Kahn vigorously characterizes the elements within these scenes, not through illustrative descriptions but through pictorial events. What does this mean? Simply put, if you look at the paintings and absorb their most elemental effect – the impact of their colors and the intervals between them – you’ll gain, sooner or later, an uncanny sense of presences filling the surface, and even your relationship to them. Kahn’s colors are keenly active, not in simply pushing forward and back, but in their pressures across the surface. They turn her compositions into spacious but tightly-knit meshes, with each color – whether spreading as open space, condensing as detail, or connecting as a tensile gesture – leveraging the next. Certain idioms prevail in these paintings, such as the sequences of twisting torsos, palpably at one’s eye level, with heads tangibly above, turning this way and that, and the legs flowing inexorably towards the canvas’ lower edge, upon which they often rest. Spend time with these images, and you’ll realize that nothing exists except through color impulses; pictorial conviction so eclipses literalistic rendering that a single vertical may just as adamantly support, at the same time, the bodies of a human and a horse.”

from John Goodrich review of Deborah Kahn’s solo exhibition at the Bowery Gallery in 2015, from onviewat.com

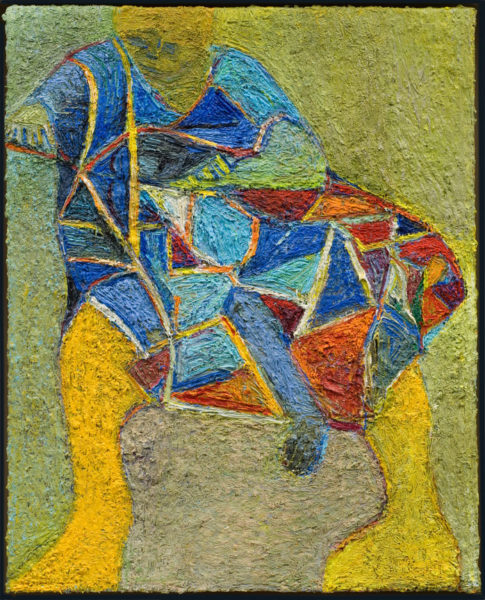

“The pressure that I put on myself is to make paintings where there is no separation between color and drawing, and where space has no beginning and no end. Nothing can be separate–everything is part of a continuous space. The image, the skin of the paint and the colored marks are one. Like living things, my paintings must appear as masses that cannot be penetrated.”

Warren Craghead, a Charlottesville, Virginia based critic, wrote: “The real star of the show, and night, was Deborah Kahn. Her thick almost carapace like paint surfaces represent high abstracted figures, but they also do the impossible – they seem ossified into hard shells but still have a lightness and flexibility that’s astonishing. She makes dirt move while just sitting there…”

“I want my paintings to be like a turtle’s shell: ugly, craggy and at the same time a beautiful shield that contains the history of the creature and its kind. I want my paintings to feel like dirt that moves.” Deborah Kahn

Larry Groff: What made you decide to become an artist?

Deborah Kahn: I don’t know what made me decide to become an artist. When I was a young child I don’t remember drawing or painting that much, nor was I a naturally gifted draftsman. My childhood and teen years were about reading, not making art. I grew up in a house filled with books. Everyone in my house was constantly reading, so books were my passion and escape. My mother and brother were very musical, so there was lots of music at my house. My father, tone-deaf, loved music but his passion was poetry and philosophy. I identified with my father and spent many nights listening to him recite poetry and lecture me on Plato and Aristotle. This doesn’t answer your question except to say that I grew up in a house where art, truth, and beauty were revered. And, I grew up believing that the artist’s life in pursuit of beauty and truth had meaning and value.

As a teenager, I enjoyed drawing and painting. It was just something that I did, but it wasn’t a passion. But because I liked to draw and paint, during my senior year in high school I applied to a few undergraduate art programs and was accepted into Boston University, Fine Arts Department (BU). I wasn’t really happy at BU, so after my sophomore year, I transferred to the Kansas City Art Institute. The Kansas City Art Institute was a great school for me – I loved it. I primarily studied with Stanley Lewis and Wilbur Niewald. Both Stan and Wilbur were fantastic teachers. They created a learning environment where students worked hard and were excited about learning the language of painting and drawing. It was at KCAI where I began my life of learning and loving painting and drawing. – I haven’t looked back since.

LG: Why weren’t you happy at BU?

DK: I didn’t do well at BU. Drawing was an important part of the curriculum and modeling form was the way the professors taught drawing. We would isolate the figure on the page and try to create volume and light by crosshatching. I could not crosshatch neatly and fluidly, so I didn’t do well in their program. I was an awkward draftsman, always getting angles and proportions wrong. My drawing teachers would say that my work was interesting but I would always get a low B or C on my homework, no matter how hard I worked, so I became discouraged and left after my sophomore year. It just wasn’t the right school for me.

LG: Can you say more about what art school was like for you?

DK: After my sophomore year, I went to Boston University’s summer program and met a few students from Kansas City Art Institute (KCAI). I liked them and was impressed by their work and their excitement about making art. I decided to apply to the KCAI. It wasn’t hard to get in, so I got in and went out to Kansas City to study painting and drawing. It was at the Kansas City Art Institute where I was taught to look at relationships, angles in space, planes, and shapes on the page. Looking at relationships helped me to draw from observation more correctly. The problems of drawing from perception are what Stanley and Wilbur talked about and they introduced me to the importance of Cezanne and Giacometti. As teachers, they both encouraged me and it was through their encouragement I gained confidence as a young painter. It was an exciting time for me.

I liked living in the Midwest. It was so different from anything that I knew and the painting program at the Art Institute was spirited – I felt that I was part of a great program. I made good friends at the school; we painted and discussed art day and night, and the competition amongst the students was good-natured. We were learning about looking at the world through the language of painting and drawing. Our teachers had us draw and paint from reproductions and art at the Nelson-Atkins Museum. It was a great education and I feel lucky to have been able to study at the Art Institute in the seventies.

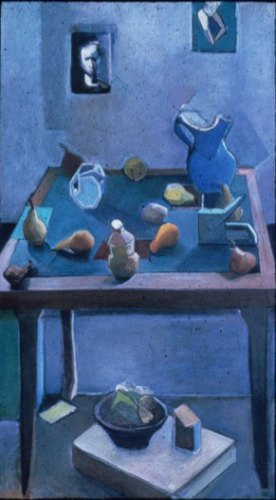

After graduating from the Kansas City Art Institute, I went to New York City and got a waitressing job at a jazz club. My hours were crazy. I would get home around 5 or 6 am and would sleep all morning. In the afternoon I painted in my very small apartment. Working from observation, I painted a large still life triptych and made small studies of the still life. I also painted life-size self-portraits. It was the work that I did during my two years in New York that I used to apply to graduate school.

After living in New York City, I went to graduate school at Yale University. In my studio at Yale, I continued working from the still life, but it was a very different experience than I had while being in undergraduate school or alone in my NY studio. At Yale criticism was the method the faculty used to challenge the students to explore new ways of working and to learn to question preconceived ideas about art. It seemed to me that everything I painted was criticized – there was very little encouragement. It was a hard time, but I learned a lot. I learned to challenge myself, which was invaluable. Being young and naive, I was exposed to a broader art world. Students were doing different things and were very competitive. It was a great experience, but as I said before it was a difficult time.

I can remember Al Held, one of my teachers at Yale, constantly telling me that I was not interested in the still life, despite my singular focus on painting the still life. It was confusing, but I trusted him and slowly started looking more at abstract painting. He kept encouraging me to look harder at abstract painting and he told me to study Matisse’s The Red Studio. Although I made studies of other artists and respected Al as my teacher, I was stubborn and did not listen to his advice about studying the The Red Studio. It wasn’t until four years out of graduate school that I did a copy of The Red Studio and after studying it my work radically changed–I began to focus on constructing non-observed color in my paintings. And that pursuit has continued.

After graduate school, I returned to New York City. Working several part-time jobs, including teaching a class at the New York Studio School and a design course at the Fashion Institute of Technology, I again painted in a small apartment. My painting process at that time was compartmentalized. What I mean by compartmentalized is that I would work on many different kinds of paintings simultaneously. I painted large and small, quick and worked, abstracted and observed still life paintings; painted numerous studies from reproductions; made a series of portraits of objects; constructed invented paintings of women in interior spaces and did quick abstract paintings on paper. These paper paintings were like automatic paintings and they became very important to my development.

LG: By automatic painting do you mean like how some Surrealists or Abstract Expressionists might make?

DK: No, not exactly. My large worked paintings were abstracted from the source, in the European tradition. These quick paper paintings were also painted looking at sources but were done in one or two sittings without using subtraction as a means of correction. I didn’t change any decisions but rather edited by throwing away hundreds of paintings and only keeping a small number of visually interesting ones. Out of ten paintings, I might keep one good one.

I eventually got a job teaching painting and drawing at Indiana University (IU) in Bloomington, Indiana. During the four years that I taught at IU, I continued working in the same manner that I had worked in New York. I continued painting large and small still life paintings and making studies from reproductions. The quick paper paintings became quite large, working on pinned papers on the wall. It was in my Bloomington studio where I first made a painting from Matisse’s The Red Studio and I did a series of paintings that were inspired by what I had learned from Matisse. I did large paintings of my studio where I invented the color – the color was not observed. The paintings, for me, became about the dominant color that I was using and the relationships between all the colors in the painting. This forced me to construct the paintings more and not just respond to what I was looking at. For example, I did a yellow painting with a pink house out of the window. The painting was about the relationship between what was happening inside the overall yellow interior space and the pink house outside the window. This manner of working was new for me–I was thinking about moving the color through space. Of course, I got this idea from Matisse.

Matisse, Henri. 1869-1954 The Red Studio, 71 1/4″ x 7′ 2 1/4″, Oil on canvas, 1911, collection of the MoMA

LG: Can you say a little more about what you mean by moving color through the painting?

DK: Let’s say you are drawing your room. Your charcoal hits the page and you start designating where things are located, the proper angle of the windows, the bookcase or table. The drawing is about many things, but it is also about how the mark transforms the white of the page. Now imagine that your page is red and your lines are different colors, not the color of the red page. As you indicate your objects on the red surface, you watch how the red moves and how it changes its character, its weight, and its position in space–Like Matisse’s The Red Sutdio. In Matisse’s painting, the red asserts the flat surface of the rectangle, while simultaneously becoming form and space. The painting is about a lot more, but this is what I mean by moving the color through space.

I want the light to come from the color and the color to transform into the illusion that I am creating on the canvas. I think everyone thinks about this in different ways.

LG: I think it’s very healthy to find new ways to think about color. I used to think about color more in terms of naturalism, trying to mix a color that matches the observed color as close as possible while at the same time have this color meet the painting’s needs as well. However, thinking about color only in what the painting needs–with a more abstract sensibility–can be very difficult. How do you verify if the color is right? How do you decide the weight, tone or temperature of a color when you have nothing out in nature to compare it with? Perhaps invented color scares me sometimes because it can seem too ephemeral or arbitrary.

DK: This is a very hard question to answer. Color is everything to me. My color choices may appear arbitrary, but it doesn’t feel that way to me. For me, the color contains the reality of the entire painting. I am not a willful painter – my choices come from my process. My manipulation of the color is structural, which is cerebral. I struggle to make space in my paintings and that means the color must not appear flat. That is the key idea – color must not feel flat. The space in the painting can be shallow but not flat. The color has to move, contain light and appear as convincing forms. In the end, the painting is the color and the color becomes the form.

LG: Have you ever read Kandinsky’s book on color, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, where he wrote about the emotional qualities of colors?

DK: I’m familiar with it but I never really read it.

LG: I only read a few parts of it years ago. As I remember, it was a difficult read. Not that it was too dense or difficult but more in terms of accepting what he was saying about how color affects emotion, like yellow is disturbing and blue makes you feel good. Color and emotions are too subjective, too personal. I didn’t buy into his theories despite liking what he did with color in his paintings.

DK: I know what you are saying, but I never think about the relationship between emotion and color. In my paintings, I tie color to figuration, so it may appear that I think about color emotionally, but I don’t. Color for me is the ultimate abstract element. Like light it exists outside our emotions. What I think about is structuring the color, moving it through the space of the painting, transforming the flat surface of the canvas into volume and form. I don’t separate color from space in a painting. I think about how the color changes its sensation, its weight and how light or air comes from the color.

LG: Can you talk more about how your work has evolved over the years?

DK: We have already discussed my development through 1986, the year that I left Bloomington Indiana. My former husband and I moved to New Haven because he was accepted into the Yale graduate painting program. While living in New Haven I was an adjunct professor, teaching undergraduate drawing at Yale and commuting to NYC to teach a beginning painting class at Queens College. After living in New Haven for two years, we returned to New York City.

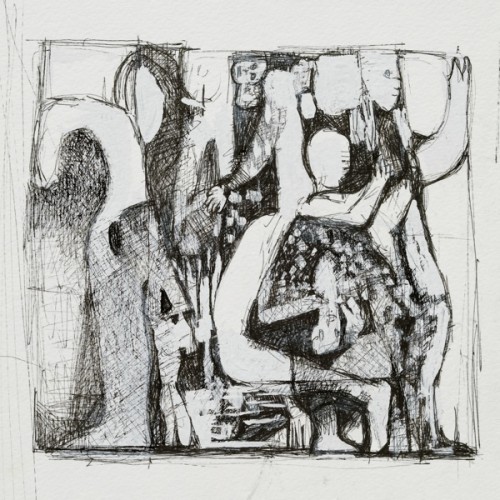

During the two years living in New Haven and for at least two years afterward, I primarily painted large abstract paintings. These paintings were inspired by the “automatic” paper paintings that I was doing in Bloomington. As I already mentioned the “automatic paintings were responses to looking at the still life, but the images in these paintings contained tiny fractured broken marks of color and the spaces were less figurative than the more worked paintings on canvas. I felt that the automatic paper paintings were my best work, so I decided to study them. I did a series of pencil drawings responding to the small fractured marks of color using dots, dashes and small lines. This manner of drawing slowed my process down and changed the way I drew. I realized that I not only needed to change my subject matter but how I made my paintings and drawings.

In 1989, I was hired to teach in the Studio Art Department at American University in Washington D.C. I commuted from New York City for several years. My former marriage started breaking up in 1991. That year I stopped commuting and set up a studio in my small apartment in Maryland. I was depressed during my separation and then divorce. (I think the depression lasted for around ten years.) During those years, I was very involved in Jungian therapy–I feel the therapy influenced my work, but I can’t say how. I do know that my sadness affected my work and my process. I focused on making one painting at a time, rather than working on many different paintings at once. I worked slowly and stopped problem-solving. My goal in my studio was just to paint. The paintings were small and the images were simple. They were quiet, contemplative, non-objective paintings. The colors changed over the years, but for a little over ten years I painted small silent paintings. Although they appeared geometric, I saw them as containers for the body. Figures seemed hidden inside the veil of the paint.

Over the past 20 years, figures have been emerging from the paint. I have continued to work on only one painting at a time. As a release from working months on one painting, I draw. I see my drawings as doodles–drawing made without listening to my critical voice. Often I make studies of old master reproductions. I think the study from reproductions of old master paintings has had the greatest influence on the evolution of my work. As I move from looking at one artist to another my work changes, but it is slow and definitely not a linear progression. For example, around 2006, I primarily drew from Picasso, Medieval, Greek and Indian sculpture. The images I painted were of abstract figures interconnected as though in a dance. The color was somewhat saturated and the paint was thick. I wanted the figures to appear sculptural inside a shallow space. My new work, since 2015, has become more tonal; the paint surface is thinner and the figures are small. The space around the figures is larger and deeper; often there is an imaginary landscape out the window. In the studio, I look at so many artists, but I think Goya is the artist that I have been looking at the most for the past two years. (Although, I am not sure that you can see Goya in my work. I wish you could.)

In the end, what drives my work is my desire to understand more about the language of painting and drawing and to make better work. My studio practice has allowed me to live a life of learning and although I am rarely satisfied with my paintings, I feel very lucky to be a painter.

LG: So say we all! I’ve often thought that the most interesting painters tend to have that attitude.

LG: You are preparing for a solo show coming up next April at the Bowery Gallery. When you are working for a show like this – do you plan for the work to be unified around a theme or explore a range of related visual issues?

DK: No, I don’t work to create a unified theme and I don’t think about creating work that explores related visual issues.

DK: In the studio, my desire is to keep improving and learning. Often a new painting is a reaction to problems in the previously completed painting. I just show the work that I have done since my last show. Exhibiting gives me distance from the work. That distance often shows me where I need to go. I have been thinking that after my next show I may rework a finished painting, just to see what would happen. I have never done that. The problem is that it may look like a new painting and not take the old painting any further.

LG: Maybe what you learn in the process of reworking the painting could lead to major shifts and directions for your future paintings or conversely, it could just be a waste of time.

DK: I think that it would be hard to rework a finished painting just for the sake of reworking it – just to see what would happens.

LG: Why is that?

DK: The decision to stop working on a painting and to decide that it is “finished” is very important to expression. It is also difficult to define. My paintings feel complete when they feel real. Every painting takes months to complete and I leave them when they feel like they are the best I can do. Completing a painting is exhausting and intense for me. The idea of reworking something just for the sake of change is hard for me to think about. But it might be a very good idea. Imagine taking your favorite painting and reworking it.

LG: Interesting. Most of your paintings that I’ve seen are readily identifiable as having your DNA. I’m curious if you have thoughts you might want to share on this?

DK: I am not sure how best to answer your question. That may be true for all painters.

But I know in my case, I keep trying to learn how to make form. I primarily do this by drawing from what I believe to be great works of art. Often, I feel that I am searching for painting’s formal rules. In a way that seems radical. After all, many artists try to break the rules. I am looking for the rules because I don’t feel that I know very much. Simply put, I see my process as a search for formal elements that create the illusion of space on the flat surface of the canvas. This is in keeping with a long tradition of painting.

Figurative painters, who work from sources, use concrete objects to guide their decisions. If you paint an apple, the hope is that the painting reveals specific observations about looking at the apple. (You talked about this earlier in our discussion about color.) I create imaginary worlds and I have no specific visual sources to help guide my decisions, but I need external help. Primarily what guides my painting decisions are formal constructions that I learn from looking at old master paintings. My work is not just about looking for the rules, but it is a big part of my process. However, my deepest hope is that my painting decisions will present my mind and heart on the canvas.

When I paint the only thing that I think about is form – how to create space, light, and forms that move. But, when I am thinking about meaning in my work, I move into the realm of belief and hope. Therefore, I would like to add that I believe that art is the language of emotion – and form is the element that contains emotion. (Susan Langer talks about this idea in her book, Feeling and Form.) And I also believe that emotion and art contain coexisting contradictions. A person can feel joy and sadness at the same time. In painting, formal contradictions also coexist: an image can appear flat and volumetric, moving and still, or beautiful and ugly simultaneously. My paintings are an attempt to make this idea visual.

I love what Flannery O’Connor writes in The Nature and Aim of Fiction. She states, “Art is selective, and its truth is the truthfulness of the essential that creates movement.” Again, movement for me is created through the structuring space. I want forms in my work to move from one reality to another – Figures flip from real to illusive; they move from male to female, or animal; objects can be namable or unnamable; places seem real and unreal. The following idea may be a stretch, but I see fluctuating movement in painting as a metaphor for the mind’s fluid movement between consciousness and the unconscious. Painting for me is a controlled connection to an inner world.

I think we should end here. Otherwise, I will keep rambling on forever and my thoughts may begin to sound more out-there. In the end, the act of painting is simple – I paint because I have to – and for no other reason.

Larry, I have really enjoyed talking to you and I would like to thank you for taking the time to interview me and for putting images of my work on your blog.

LG: Thank you so much, Deborah, for your time and energy with this. I will look forward to seeing more of your new work for your Bowery Gallery show in April.

Hey

Love this interview

Love the paintings

Love it all.

Debbie Kahn, your paintings kick my ass.

Just stumbled across this interview. Many salient point made about moving from strict observational work toward more personal work through manipulations of space, color, planes, relationships, and movement. I’d love to see some of her student’s work!