David Gloman is a Northampton, Massachusetts based landscape painter. He has been the Resident Artist at Amherst College, Amherst, MA since 2008 and who has had various solo and group exhibitions in New York and New England. Gloman received in 2005 the John Simon Guggenheim Fellow, New York, NY and in 2004 the Blanche Colman Award, Mellon Trust, Boston, MA 1998 the American Academy Of Arts And Letters – Hassam, Speicher, Betts, and Symons Purchase Award. New York, NY.

Larry Groff Thank you Dave for your generosity with agreeing to this interview and for the time and care with writing your responses to my questions. Let me start by asking you my standard, “How did you first decide to become a painter?”

Dave Gloman I wasn’t a great student in school but always considered myself creative. I drew a lot from cartoons and my imagination. I was really interested in the Civil War, so I drew all the generals, battle scenes and that kind of thing. I also liked and participated in all sports, so I drew my football heroes. I think I got straight A’s in gym and art; a strange combination. I started painting in high school but didn’t think it would lead to anything. My athletic career was over because of a football injury during my freshman year. I didn’t know what to study going into college, so I thought I’d try art and minor in American history, so I could teach.

I studied at Herron School of Art in Indianapolis for a month and dropped out, returning home to live for a year. I started back at school the following year at a branch campus of Indiana University with the hopes of eventually going to the main campus of Indiana University in Bloomington. It wasn’t until I got IU Bloomington when I really thought I could become a painter. I think it was my sophomore year when I started to take it seriously and devoted all my time to painting and have never looked back.

LG What was art school like for you?

DG I came from an extremely conservative family growing up in Fort Wayne, Indiana. I wasn’t exposed to art at all except for a few reproductions in books and illustrations from my Civil War books. The idea of art school was foreign, unknown. I didn’t know of anyone who went to art school. My exposure was, to say the least, eye opening and incredibly expansive and at times frightening. I was kind of awkward and weird and found other awkward and weird people who liked the same things as me. At Indiana, there was a program separate from the regular undergraduate classes called the BFA program. It was select. You had to apply with work and it was a minimum of two years. You had a separate building to working in, your own small studio you shared with other BFA errs. There were weekly critiques with all the professors and it was extremely competitive. Critiques were rough! There was this subtle hierarchy among students. You would be put on probation if your work was not up to par.

This is where I developed my work ethic. I painted all the time and made as much work as possible. I devoured art books and became very serious about making paintings. I grew so much in those years. I remember everyone talked about going to the Yale at Norfolk summer program during the summer. That was a ring everyone hoped to grasp. At the time it seemed so out of reach for me. I just kept working and found out later that I was nominated by my professors. That was the summer of 1982.

Yale at Norfolk was a life changing experience for me. I met so many different painters from all over the country. Really good serious painters. I had my first exposure to the Yale school of Art, which at that time was THE place to go to learn representational painting. William Bailey, Bernard Chaet, Andrew Forge, Jake Berthot, Roger Tibbets, Natalie Charkow were some of the teachers there. The program was really competitive at Norfolk, so you had to work. I made a shit load of bad paintings there which was very important for a beginning painter. That’s was and still is a major part of my process. That was the best summer: Breakfast, paint, lunch, paint, dinner, paint and Beer, Beer, Beer!!! It was great to be exposed to all of these different points of view. I painted outside that whole summer and came back with a greater appreciation for abstraction: for something beyond appearance.

I really felt I learned how to start putting a painting together. Roger Tibbets who taught at Yale Summer School of Music and Art and now teaches at Mass College of Art was a huge influence on me that summer. Got back to Indiana that fall with some confidence and started painting landscapes again. I tried some huge painting outside of the house I was renting, 5×7 6×8 and plein air. I would have cans of enamel paint all over the ground and I painted with house painting brushes tied to dowels. Gradually, I started painting more indoors.

I was awkwardly trying to merge abstraction with observation and struggling. I started to deconstruct my outdoor landscapes into simple planes of color like de Stael and some of Klee’s color square paintings. I liked Hans Hoffman’s paintings a lot. I was looking at a lot of abstract painting, Newman, de Kooning, Rothko, Jasper Johns, Franz Kline, Ad Reinhardt, Ellsworth Kelly. Formally, I sort of pulled apart all of my landscapes into pieces and really boiled them down to almost nothing: very minimal. Mondrian’s arc of his work was huge at the time for me. I rarely painted outside for 3 years.

When I graduated I wanted to take some time off before I applied to grad school. It was risky as some advised me to apply right away while “the iron was hot”. Instead I got a job mowing grass and digging graves at a municipal cemetery. No one I worked with had gone to college and that year of working was one of the best educations I could ever receive. I worked 40hrs a week, got off work and painted in a tiny apartment. No crits, no feedback, just painted. I wanted to see what it was like to paint on my own. I was doing these abstract paintings that looked a bit like some of De Kooning’s later abstractions.

I got accepted to the Yale School of Art in 1984. At the time that was THE place representational painters would go. Some of the friendship I had at the Yale Summer School of Art. Carried over to grad school. Some of the same people got into Yale Grad school. Back then there was quite a connection between Indiana and Yale. With both schools trading undergrads to grads. The BFA program at Indiana was a mini version of Yale’s Grad program and equally as challenging. Yale was rough. Very competitive and you were expected to work all the time. It was obvious from the beginning that some students really worked hard at becoming Art Stars and actually succeeded. I could care less. I painted a lot and tended to isolate myself the second year, so I could just concentrate on painting and not be distracted by all the drama. I really honed my work ethic at Yale. I learned to stand up for myself and my painting and I learned discipline and focus.

I also learned, and Yale is notorious for this, Art speak! It was almost a requirement before you graduated! Looking back on it, I really valued what I learned there. I left there with a better understanding of how to put a painting together.

Katy and I met the Feb of my last year and when I graduated I was accepted in the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown for a 7-month Residency Fellowship. It was a great way to leave grad school and gave me a chance to start exorcising all the grad school demons.

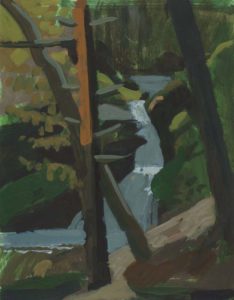

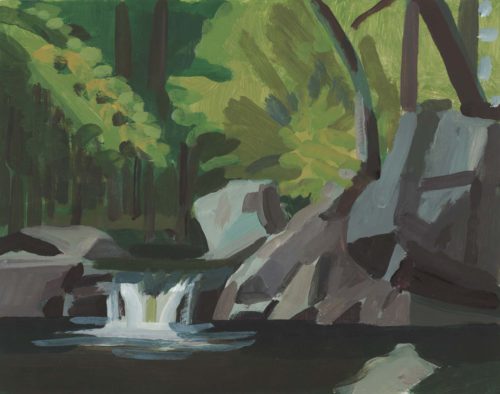

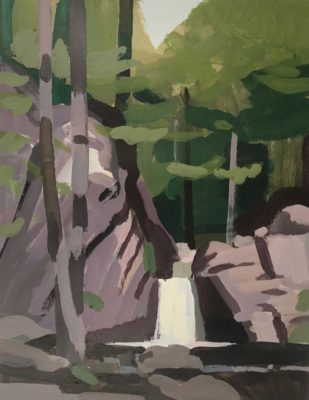

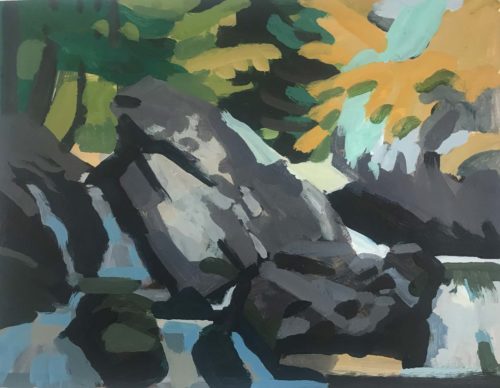

Money Brook Falls I, 11×14 inches, Acrylic on Paper

LG What influenced you to become a landscape painter?

DG I was always outside as a kid. I was extremely rambunctious as a kid and to preserve her sanity my mom would shoo us all outside to play. My socialization took place outside, my imagination was limitless outside, and I learned so much about the natural world outside. There were cornfields and woods and ponds around my house so most of my time was spent exploring and imagining. I always had a sense of a deeper history to the landscape, pre-people, primal. I felt something that I could not put into words. The light, weather, seasons, smells, sense of space and belonging. I guess I felt the most alive and independent outdoors in the landscape.

When I was an undergrad at Indiana in the early 80’s. I painted a few landscapes for a class I was taking. At the time I was mostly painting people and very simple narratives. During critiques those paintings garnered some attention. My teacher at the time Bonnie Sklarski suggested I go outside and paint.

That idea seemed so foreign to me. I started painting outdoors and something really clicked with me. I sensed those same things I had as a kid but was able to sift through all those sensations with paint.

LG You are married to the amazing painter, Katy Schneider, and raised 3 children(?), from what I understand, your wife mainly paints indoors, interiors and still life – while you paint outside, how has being married to a painter affected you?

DG Yes, Katy is an amazing painter and my wife!! We’ve been together for 32 years and have three semi-grown children. I was a grad student at Yale and she was an undergrad art major at Yale when we met. We both were in love with each other’s paintings before we actually met in person and there was no looking back. We have very similar philosophies about painting. And I have learned so much from her. She is extremely gifted and makes painting look effortless but works her ass off painting. Her work ethic, focus and relentlessness have been inspirational to me.

Being married to a painter certainly has advantages. We understand the commitment necessary to have a life as a painter. We respect each other’s need to do this and the space and time required to do it. Raising three kids while only having part time jobs at the time was challenging. The fair distribution of time was difficult to balance, but we managed. We’ve both had our successes and failures but still keep working and supporting each other.

Katy paints more intimate subject matter and has a knack for capturing the tactile quality of things. She has an intense connection to things and people and that carries over so beautifully in her work, our shared love of light, form and paint on the surface really binds us together

I love space, air and don’t have the same connection to things. I actually try to paint no things, which says something about the spaces I grew up in in Northern Indiana. Wide open and lots of distance between things.

Katy grew up in midtown Manhattan with 9 people in a small two-bedroom apartment. Space was very limited or practically non-existent and your possessions marked your limited space. It’s interesting how that stuff influences our work to this day.

LG What, if anything, is more important to you now compared to what you were doing 10 or 20 years ago?

DG I don’t know if my paintings have evolved. I think it’s cyclical and like a spiral. I revisit ideas with new experiences and knowledge and new mediums. I really think some of my most recent paintings are similar in ways to my paintings when I first started 30 something years ago. There was a freshness in my earlier paintings because I didn’t know anything about art, about making a painting. It was pure experience and my newer paintings are similar in that I’m trying to not know what I’m doing. I want my mind, my knowing, my analytical side to be silent. I want the experience in the moment to be as present as possible.

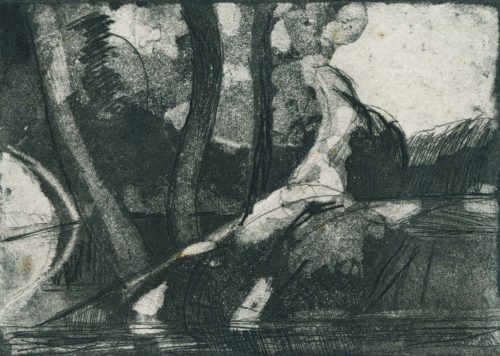

With that said, I think my drawing and color are much more specific than ever before. I’m able to do things in the painting much more quickly and efficiently. I think that that comes from doing hundreds and hundreds of paintings. I try not to think pejoratively about my work. It’s not good or bad or successful or a failure. It is not more or better than before. It is what it is in that moment. That to me is extremely liberating. I’m still extremely interested in the transitory nature of light, light and matter and geometry. The idea of space and light have also been present from the beginning. I have also expanded my use of materials and mediums. I regularly switch to ink wash drawings, watercolors, collage, Lino cuts, etchings, gouache, markers. Occasionally, I sculpt with plasticene and cardboard.

LG Much of your painting seems to be done alla prima. Do you ever work further in your studio away from the motif? What are some of your thoughts about this?

DG I used to paint a lot in the studio during grad school. I was very concerned with how to put a picture together. I always associated work done in the studio as work done from my head: from ideas rather than from a direct source. I was totally obsessed with Corot, Constable, and Turner. One of my professors, Jake Berthot really influenced me with his love of the surface and marks sitting in very specific places in space. I would make up landscapes. I’d paint layer over layer building up a very textured surface. I painted with a palette knife on panel. I would scrape away and put down transparent layers then impasto over that. Very labor-intensive paintings. Atmospheric and romantic.

At Yale, Bernard Chaet kept urging me to go outside and paint. Towards my last year I started going out more and my process changed. I had to work more quickly because everything changed in the landscape so fast. The paint reflected my response to a source rather than trying to convey a conceptual idea.

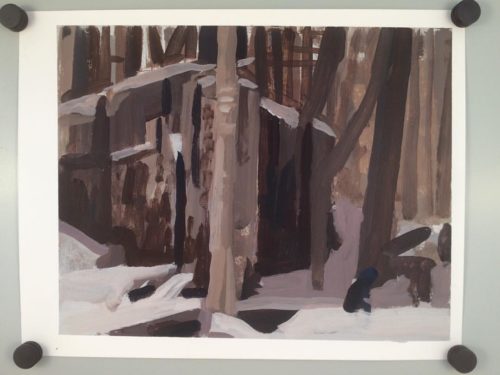

Recently, since I don’t have my painting truck I haven’t done large paintings outside. Katy suggested I paint larger paintings inside from smaller ones that I painted outside. I’ve had limited success trying that. I feel very limited doing that. My imagination and invention pales in comparison to the complex structures found in nature. I could never in a million years come up with some of the complexities and subtleties I encounter when I invent from nature.

I’m concerned with the immediate direct experience when I’m outside painting. I’m trying to capture the present moment not an idea of the moment or a memory. The majority of my newer paintings are one shot. I don’t edit myself at all. To edit myself is to be disconnected from the moment.

LG You wrote in the artist statement on your website:

“…I hope to capture my relationship to the world by exploring and giving form to the space between myself and objects. I am trying to paint what is not there. They are not paintings of ideas rather paintings of direct experience. They are more about the journey of looking rather than the complete end result of looking. Conscious rather than self-conscious. Open ended.”

This is such a brilliant way of explaining why many people want to paint from life. Could you explain more about how this “conscious” painting is visible in a specific painting?

DG I remember one time I was really locked up with my work. I didn’t have (still don’t) a gallery, nothing sold, my work was stuck as I was doing the same thing over and over and I really started to not like painting. I would edit my work before I even started. Overly critical and worried about what other people thought. The act of painting was very self-conscious. Someone suggested to me to do a painting and turn it to the wall. Don’t look at it just turn it to the wall. She also asked me what would one of your paintings look like if no one saw it but you. That free me up in the most profound way.

I think of conscious as a kind of mindfulness. The kind of flow that happens when you stop trying to control things and just let it be. Being as present as possible in a place is what I try to practice. There really is no right or wrong experience. It is what it is! My paintings really changed when I started practicing mindfulness. Painting became much more enjoyable and I find myself be more open and accessible to the world.

LG What role does direct observation play in your work? Do you ever paint from drawings or studies? How important is it that the painting should be about the experience of looking into and at nature rather than painting the appearance of nature?

DG Direct observation is very important in my work. I couldn’t possibly think that I could come up with the experience of landscape without being in the landscape. The wind, bugs, smells, sounds, light, and temperature can’t be experienced in a nice comfortable studio. The work generated in that studio environment is more about memory or tend to be very generalized or about the idea of landscape or some formal idea. It looks very even. There is an inherent flatness that lacks a sense of space. Believe it or not I invent better when I am directly observing the landscape. There is no way you can copy nature and the appearance is only the tip of the iceberg. I find the landscape so complex that it’s an endless source of information. I find myself sifting and boiling down that information to what I feel are the essential elements of that place. The painting is a record of my experience in that place at that particular moment so there is no right or wrong. The editing that I do is about finding that sweet spot for all the colors, shapes and marks of paint. I not as concerned with learning the language of paint like I was when I was younger. After 30 years of painting I feel like I’ve developed a fluent language, so I don’t have to worry or think about that when I’m painting. I try not to think about what the painting means. It’s taken me a long time and many, many paintings to arrive at a level of fluency where I can just be present with the paint. I remember Paul Resika saying that it takes about twenty years just to begin to understand painting. I’m a firm believer in that. Everything is so quick now and I’m afraid that that sensibility will be lost.

Through direct observation and painting plein air I have had to learn to paint very fast. You notice light changing every 15 minutes. A storm could pop up and you have to finish fast. Going back to the same spot over and over (which I used to do) had its challenges as well. The place changes day to day, week to week, and year to year. That is one reason why I do one shot paintings. I ended up repainting the painting every time I went back out to the same spot to paint. It was more of an accumulation of many experiences. The paintings really ground to a halt when I did this.

Occasionally, I have worked from drawings and paintings. Stanley Lewis and I have studio visit frequently and we talk about working from master paintings. I’ve copied some Ruisdael’s and Courbet’s and a Koussin painting and find that to be extremely satisfying. Trying to climb into their heads and see how they construct landscapes is a really great way to learn. It’s an old practice but so extremely valuable. I don’t know if students still do that. Every so often I’ll start a painting inside from smaller paintings but find that extremely limiting because of the lack of information. I’m not interested in doing a painting of painting. Seems like there is a lot of that these days: paintings of ideas of paintings. For me it’s too far removed from life and the world.

LG The landscape drawings of Poussin and Claude might seem to be influential to your work. What might you be able to say about how their work has impacted you? What other painters have been significant to you and why?

DG Yes. I love those two painters. They have developed a structure and geometry of space that comes from direct observation. I’ve see Poussin paintings outside. All of these conventions (hate that word) come from nature. The physics and engineering of a painting can be found directly in nature. They are the original source for Western landscape painting. There is a very strong lineage of landscape painters throughout history who are indebted to these two. The Barbizon painters, Hudson rivers school painters, impressionists and on are influence by the classical landscape painters.

I was always drawn to The Hudson River School painters. Their attempt to deify, tame, romanticize nature seemed so reflective of where our country was at that point. The metaphor of the wilderness and exploration were so important then.

I am deeply influenced by Corot. His sweetness for light and air are particularly endearing. He went out a lot and painted in the landscape and that seems very evident in his larger “finished’ pieces. His gentle fracturing of light into planes of color was so important for me.

I remember William Bailey at Yale talking about how Corot had a perfect sense of tonality in his paintings and how the structure was masterfully balanced. He went on to mention that Matisse had a perfect sense of pitch of color in his work.

I’ve started to look at Courbet’s landscapes recently and how outrageous his space is in his paintings. The awkward shifting of near to far and the crazy scale juxtapositions are amazing. His knows the landscape. There are plenty of Courbet’s I see outside as well.

Pissarro and Sisley were huge influences. I responded to their particularly difficult, seemingly paradoxical pairing of light and geometry. I am very much interested in that in my most recent work.

Ultimately, I respond very clearly to Cezanne. Getting color to represent light and build form at the same time is brilliant. His unique way of painting what is not there, space for example, is unmatched. His combination and integration of studio ideas with nature is the core of my painting. There is the statement he made about wanting to repaint Poussin in nature. I guess I want to repaint Cezanne’s from nature

LG How do you approach drawing in your paintings?

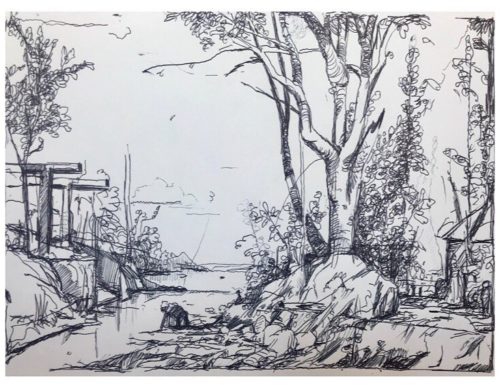

DG For so long my drawing was much more articulate than my painting. I always drew early on but drew less when I became serious about painting. When I don’t understand something in a painting or get stuck, I use drawing as a way to get my bearings and create a foothold.

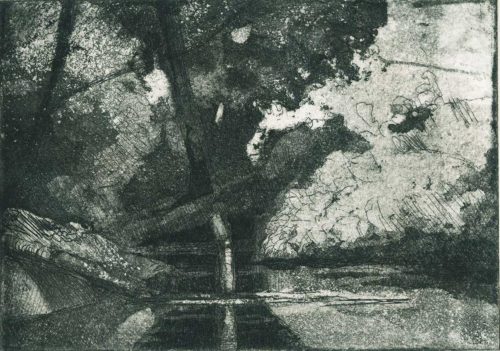

I like switching mediums a lot when I’m getting stale or repetitive, so often I will turn to ink wash on paper. I make my own walnut ink and really enjoy the interaction between the paper and any water medium. There is a real Zen quality about letting go of control and the need for control. Very “in the moment” and reactive to what the material needs to do. It’s natural as well. Think about the metaphorical and existential and practical idea of the need to control water.

I do a lot of pencil drawings when I’m painting. They tend to be diagrammatic and very linear. I find it very grounding to do drawings like this. It helps me to really clarify the essentials in a painting. A few years ago, I bought 100 3×5 index cards and a sharpie and filled those with very quick drawings. No more than 3 min on a drawing with some only taking seconds. It really taught me to get “to the point” a great experience.

Most importantly is the act of drawing in my paintings. My hand moving across the surface of the paintings and attempting to push marks or brushstroke spatially into the painting. I love that sensation when the 2-d surface actually feels like it disappears and dissolves. It’s strange that I almost feel like I’m suspending marks of paint in space. I usually don’t draw anything on the canvas first then put in color. I always feel like that separates the act of drawing from painting. I usually dive in and draw with the paint! Draw with color!!

LG You seem to use a restricted tonal palette; how do you use color in your work and what ways do you think about color?

DG I’ve worked very hard over a period of decades to address tonality in my paintings. The hundreds of ink wash drawings I do really taught me a lot about constructing a landscape space through tonality. It comes out of Claude, Poussin, Ruisdael to Courbet, Corot, Pissarro and on. Look at a Ryder or Winslow Homer right up to Franz Klein. A lot of current landscape paintings I see lack the understanding of that tonal structure.

It is a construct to make form and quantify light. It definitely comes out of nature and the landscape. I see it all the time when I’m outside. Clouds form shadows on the ground causing dark middle grounds, Trees in shadow form dark foregrounds that frame vistas and intermediate spatial zones. When I look at paintings I ask myself how it would function as a black and white drawing?

As far as my palette, you are correct in a sense that it is limited. I don’t necessarily like the word “restricted”. The color structure comes out of my understanding of tonality which is an attempt to structure and organize light. It is all an attempt at painting the elusiveness of light. I use local color as a point of departure and invention. I pare down to the essential color of the light I see. Sometimes I go out with ochre, black, white, sienna, viridian and umber. I find it challenging and extremely difficult to balance and tune just those limited colors. People mistake being colorful for being a good colorist. I think quite the opposite. Try to get an ochre to read as a cadmium or a grey to read as a blue. It really makes you think of how relative colors are and how all colors affect others in a painting. Very difficult to orchestrate. Add to that a desire to capture a specific time of day, weather, humidity and also have those colors sit in very specific spaces in the painting and you can begin to see the challenges of plein air observational landscape painting.

LG What are the considerations for deciding on the scale of your paintings?

DG How far I have to walk to get to my painting site? How much time do I have to paint before the light changes. How fast have I been painting lately?

Recently it has to do with logistics, time and my level of energy at the moment.

LG I read that you no longer use oils and now primarily use acrylics. You often seem to prefer matted and framing your paintings under glass, why is this?

DG Yes, I switched to acrylics in 2014. At the time I was painting out of a box truck that I used as a mobile studio. In that enclosed space I was painting with oils and paint thinner. The fumes got so bad that I would stumble out of my truck after working on a painting. I was getting headaches, more importantly I had done some oil painting on unprimed paper and really liked the way the paint interacted with that surface. I could paint over a stroke and it wouldn’t smear. The paper absorbed the paint. It was similar to the many ink wash drawings I have down. I tried a few paintings using acrylic and really like the way the paint stayed on the surface. There was an immediacy to the paint that I liked. Plus, it was less messy and HEALTHIER!!!!

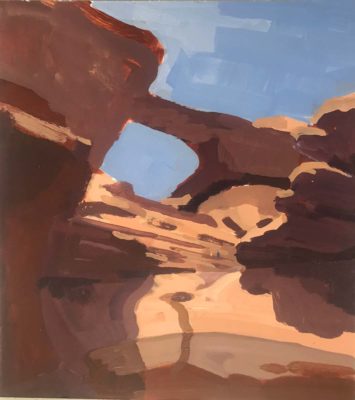

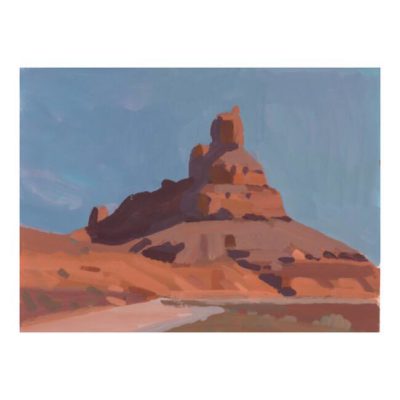

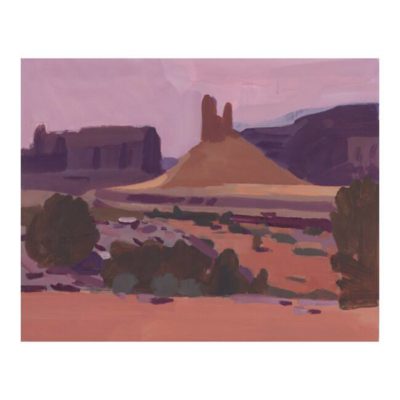

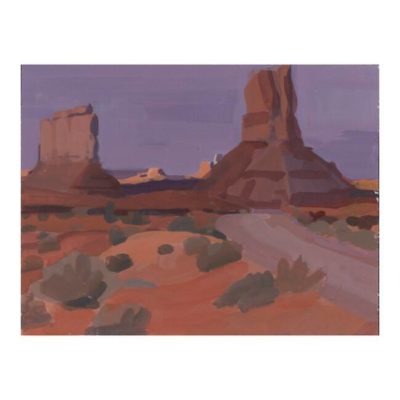

That summer I got a research grant from Amherst College for a three-week painting trip to the Southwest. I figured I’d use acrylic because I wouldn’t have to haul wet paintings around on my backpack when I was out in the field. I could do 5 paintings in a day and not have to worry about them being wet. Using the acrylic also allowed me to get further along in my process without having to wait for the paint to dry. I was able to paint 60 painting in three weeks when I was in the Southwest.

As far as framing my work, I like a lot of space around the paintings, I never put them under glass as that creates a distraction and barrier to the paintings surface. The surface of the painting is important. Seeing the brushstrokes and how the paint sits on the surface is so important in showing immediacy. Like a Van Gogh where you can see his energy and momentum in the brushstrokes. Difficult to see with glass over them or through any kind of reproduced image. I mount the paper on archival foam core and float them in a larger frame. No matting.

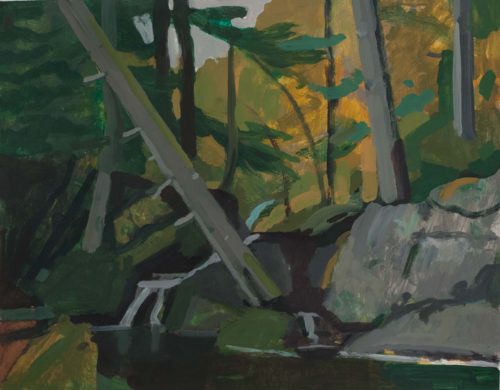

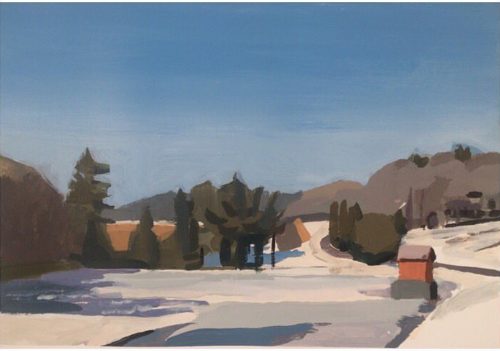

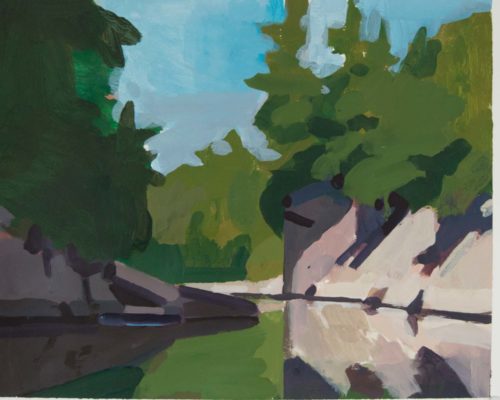

Beaver Brook Falls, Keene, 19X24 inches, 2017

LG Many of your paintings tackle similar subjects, such as waterfalls, streams, groupings of trees and rocks and similar. How important is this subject matter to you and why?

DG Subject matter is a vehicle. It very important to me. Not in the sense that there is a message that is carried in the subject. I cringe a bit when people talk about what a painting means. There is so much mediocre work that leans on subject matter. We’ve gotten so information heavy that it’s more about the subject than just trying to make a simple painting that fits together. It’s become a distraction from and actually separates from some formal structure of the painting. From my point of view there’s a kind of fractured schizoid look to a lot of work these days. A kind of simplistic layering of things. Sort of the way computers make space. Frontal, Flat and repetitive no forms or planes at oblique angles to the picture plane. Or pattern, just pattern. It’s hard to look at for me. I don’t feel challenged. The space is not interesting. Go outside. Look at how a rock is faceted, or how a cloud is constantly changing. Paint water moving. Paint a smell.

A lot contemporary work I see is way too heady for me. It looks like a book report or college paper with illustrations. Postmodern, Post-something, neo-something? Not for me.

The subject or what I chose to paint informs my color, the way I construct space, a sense of light. I tell my student’s that your painting will get much better when you paint what you love. I chose subjects that move me in a way that I don’t understand. Something that is beyond me. Something I can’t explain with words or an artist’s statement. Can I use the word “Beautiful” these days? I look for beautiful places. I don’t feel the need to know why? I use my subject as a way to release myself into the world.

I have been attracted to water for a while. Life springs from water. The effects of water on the landscape is so powerful. Water is a substance that reflects, is transparent and also has a surface. Similar to the surface of a panting.

I choose locations more on a feeling or vibe then actually thinking if it would be a good painting. Being in the Southwest and Montana and having a very limited amount of time taught me not to question why I like a spot but to just paint it! I try to trust why a spot resonates with me and use the painting to try to understand why.

Sometimes I choose locations because they are covered from the sun or offer shelter from rain or snow. Other times I choose spots because I can sit or stand. It varies with what I’m interested in and how much time I have and the amount of energy I have. There is no set rule.

LG I’ve read you have a studio truck, how has that worked out for you? I’m curious because your woodland scenes seem they would be difficult for a truck to reach.

DG Yes, my studio truck. I’ve had about three different painting trucks and every other kind of vehicle to use for painting. For years I painted out of the back of a small pickup. Hunched over, a small propane heater to keep me warm during the winter. I then bought a HUGE bread truck. 7ft ceilings and lots of space. It allowed me to paint large 4×6 painting outside (inside the truck). I then got a more reliable truck with a lift gate, roughly 7×10 and 6 feet high. I went everywhere with that truck. It truly was a tank. I think the tow truck driver in the area knew me by my first name. I would get that truck stuck way out in the woods and he would give me a look like “WTF are you doing out here?” I equipped it with a stereo system, fans, propane heater and a big comfy chair. I painted huge paintings 9×12 with that truck. I would rig up a pulley system to pull the painting up the outside of the truck and paint that way. I’ve painted from a bicycle and a moped. I’ve built two boats and did a whole series of paintings from the Connecticut River. I’ve also painted from Kayaks and Canoes. Crazy, I know.

LG You painted at Bear’s Ears and other national parks and monuments in the Southwest. What can you say about your experience painting there, any interesting stories – were you painting alone?

DG Oh man, do I have stories…

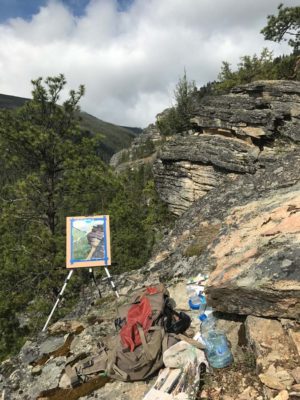

The most recent story came about during my trip the Bitterroot Mountains in Western Montana this past summer. Everyone warned me about Grizzly bears. I didn’t think much of it but did pick up a can of Bear Spray before I started hiking. Bear spray is like a very strong pepper spray. When you are alone and outside in nature after a while your senses become much keener. I love the heightened senses when I’m outside. My vision definitely sharpens I’m very attuned to what’s around me because you could become injured and really be in trouble when you are hiking alone.

Anyway, I’m hiking down this trail coming back from painting. The brush is 8 ft. high and right on the sides of the trail. I’m about 4 mi out when I see the brush ahead of me moving in an odd way. I look back up and this Black bear is running toward me at full speed. It is at least 5-6 feet at the shoulders. I just started fumbling with the spray canister that was attached to my belt. I flipped the safety off the switch and pointed it in front of me and pressed the lever spraying a large cloud of orange spray ahead of me. It got it all over my hands and I inhaled a little. The bear quickly moved off trail about 20 yards to my right. Stood on his hind legs then took off into the woods. I managed to hike back to my car. I ran across a few people ahead of me on the trail and they must have spooked the bear who ran away from them towards me. Someone further up the trail saw the same bear with cubs nearby. Let me tell you, that stuff burns so bad. My hands were burning for two days straight. I washed and washed them with water and it didn’t help. Finally, after not being able to sleep I found some Neutrogena Almond hand lotion in the bathroom of my cabin and slathered that on hoping it would help–thank god it did. From then on when I was hiking I would sing the star-spangled banner and bang a small stick I carried on rocks to scare off wildlife. My singing alone would scare any living creature!

I was completely alone in these spots. Sometimes I would hike miles and miles into the mountains or deserts. I like the solitude. The desert was a mystical place. I could understand very clearly how indigenous cultures were so connected with their landscapes. Both as a matter of survival and acting as a medium to some higher order or power. I felt that out there. I would go days without talking to anyone only dependent on myself. My sense of smell got more sensitive as did my sense of taste, hearing and most importantly my vision.

The mountains of Western Montana were glorious. Huge canyons carved by glaciers, rocky peaks, super clear water running in streams on the bottoms of these canyons. I painted a lot at altitude 8-9k feet and the light and air at that level were so clear. The scale of everything was massive and grandiose. Some of the straightest tree trunks I’ve ever seen.

The colors in those places were amazing. I remember saying to myself that I had no idea where to even begin mixing these colors. I would look at these landscapes and shake my head saying….” how in the hell do I paint that?” Everything was completely unfamiliar!!! A very exhilarating experience. I managed to paint 60 paintings in 3 weeks in the Desert and 50 in two weeks in Montana. I guess I found something that excited me!

LG What kind of space do you need to work properly? Are you able to work right away in unfamiliar terrain or do you need to gradually acclimatize?

DG I am extremely flexible and adaptive when it comes to painting. I have taught myself to paint anywhere at any time. It truly is a discipline. I don’t have time to acclimatize. Part of it is becoming familiar and acclimatizing with a place through the act of painting it. I feel much more comfortable with the unfamiliar.

By switching to being just on foot rather than painting from a truck or car or in a comfortable studio, I’m able to find places that nobody can. I’ve painted on the edges of cliffs at 10,000 feet in New Mexico, lying down on a slope at 45 degrees so I don’t slide down in Montana this summer. I’ve painted on rocking boats, I’ve painted standing in the middle of streams. I’ve painted from Caves during 100-degree heat in Utah at midday. From boats, bikes, cars, trucks. It takes a tremendous amount of discipline and focus. I really try to eliminate all excuses like; “it’s too hot”, “it’s too cold”, “I don’t have my favorite brush”, “I forgot my white paint”–all of that is a distraction. No excuses!

My recent trips to the Southwest and Montana were great examples of this. The places were completely unfamiliar to me. I had never been there. Different space, light, weather temperature, vegetation, color. I didn’t know what to expect. If I waited to acclimatize I never would have painted anything.

LG Can landscape painting use its formal, visual poetics to influence people to help protect our environment? Save Bear’s Ears and the like? Or is landscape painting function best as “for art’s sake” or perhaps just as “paintings for sale” ?

DG I suppose painting could be used for that depending on the context and the person who painted it. Paintings for a cause! That idea seems very popular and “in” right now. Sort of like propaganda or rallying for a cause. That’s fine but not for me. For me my paintings are about me being in the moment and present: about having an unadulterated pure experience. About the surrendering of self. It’s more representative of my mindful relationship to the world and my “environment” If I can take that into the world and live that maybe that inspires others.

I think that’s a much broader way of protecting the environment.

I have really struggled recently with the role and importance of a painting. What’s it functions in society, what does a painting it mean to me. What’s it value. I certainly feel that it is my only place where I don’t have to compromise. The whole attachment of money, fame, message to art really doesn’t interest me at all because that seems to be about something so far away from me living.

LG You have taught and been the resident artist at Amherst College for many years, what has that been like for you?

DG Yes, I’ve been at Amherst College since 1992 and it is an interesting place to teach” Art”. Most of the students aren’t going to major in Art so I get a lot of students who have little or no experience. I find it a very curious issue of teaching Art in an academic setting. The idea of grades, the idea of having this finite (semester) time to teach a subject. There is this awkward attempt to squeeze this organic, subtle and creative discipline into the regimented, neatly structured environment that is academia. Trying to exist and teach a nonverbal way of understanding and being in the world in an extremely verbal place. It’s actually silly at times.

Luckily, I’m given a lot of freedom to teach and I find it extremely rewarding at times. I had to learn to communicate verbally and really be able to give my knowledge to a very wide variety of people coming from many diverse experiences. It is truly humbling.

The more I teach the more I believe that the fundamentals are so important. Not just for myself but for my students. What do you see? How do you represent what you see in the clearest and most efficient way possible?

I try to teach larger life skills that are so integral in the creative process. Conceptualizing an idea or an impulse, making, creative problem solving, situational analysis. Looking at things from many perspectives, patience, risk taking, addressing fear: it’s all found in making art. My biggest fear is the elimination and fading out of the making of things. The idea that knowledge is gained through making and learning to think with the eyes and hands. I see so much work that it too heavily conceptually based with little literacy in basic fundamental visual skills. The visual is compromised by the verbal. Like I said it really comes down to teaching the fundamentals.

On the practical side, I teach 9 months out of the year, I have summers off to work on my Art. I paint when I’m not teaching and teach painting when I’m not painting. Amherst is extremely supportive of their faculty through grant funding and research monies which has really allowed me work to expand through my painting trips to The Southwest and Montana. I also teach with some amazing colleagues and in the long run consider myself extremely lucky. The biggest reward is when a student comes up to me after a class and is appreciative that I helped them see the world in a different way.

LG What advice would you give a student who told you they want to be a landscape painter?

DG Paint as many paintings as you possibly can, study nature, go outside. Look at the greats. Draw. Draw, and Draw and love painting!

I absolutely love this interview and Dave Gloman’s insights! Extremely inspirational. I am also particularly interested in just being present for the painting and hit some of the same issues when continuing a painting in the same spot which just resulted in a bunch of different paintings one on top of the other. I tend now toward the one shot paintings. His comments on content and meaning also resonate with me.

Fantastic read – thank you Larry Groff and Dave Gloman!

Oh! The Painting Truck! And the Paintings! Envious am I, since the dining room (for the big paintings) and the back bedroom (for the small ones) at least keep me safe from grizzles! Seeing these paintings –even though on a computer screen — is a shot of joy today! Thanks Larry — always enjoy your interviews.

I really enjoyed this interview. I’ve admired Dave’s work for a number of years, both for his color structures and the economy of forms in his paintings. Thanks for sharing your insights and thoughtful responses to the questions…really beautiful paintings

Thanks for this, Larry. Enjoyed the interview and really admire the economy and directness of Dave’s work.

One of my favorite interviews yet, and you have so many good ones on this sight. I was not familiar with this work and how he talks about the landscape and the immediacy of it all really resonates. Thank you!

This is a very thorough honest statement from a real painter, whose focus is on seeing rather trying to succeed or fit in. I so completely understand the importance of being inside the still moment of taking in what is ‘out there,’ without ithinking-nterference. It certainly is what I teach my students, rather than teaching anyone how to paint. One can’t; it’s always an experiential, humbling trusting conglomeration of moments that take years of painting to come to enjoy. One of the reasons I enjoyed this interview so much is knowing that there is yet another painter whose painting has become only more pleasurable in time, rather than the struggle of hard labor we all put in those years back. Now, we can fly, and do. Thank you Larry for your insightful questions, and Dave, for being inspirational, especially when you speak of painting the things you don’t see, such as the space between things, the light, composition and compositional structure that just fall onto the canvas, (rather than being built with nails and hammers and axes of the old days). One question: will you build a more elaborate truck that can also float, and maybe fly? (!)

.

I’m a little late coming to the party having only recently found Dave’s work. This filled in my curiosity of “the truck!”

But more I learned and now appreciate the life long commitment and work of a painter. Well done.